Abstract

Outer hair cells (OHC) function as both receptors and effectors in providing a boost to auditory reception. Amplification is driven by the motor protein prestin, which is under anionic control. Interestingly, we now find that the major, 4-AP-sensitive, outward K+ current of the OHC (IK) is also sensitive to Cl−, although, in contrast to prestin, extracellularly. IK is inhibited by reducing extracellular Cl− levels, with a linear dependence of 0.4%/mM. Other voltage-dependent K+ (Kv) channel conductances in supporting cells, such as Hensen and Deiters' cells, are not affected by reduced extracellular Cl−. To elucidate the molecular basis of this Cl−-sensitive IK, we looked at potential molecular candidates based on Cl− sensitivity and/or similarities in kinetics. For IK, we identified three different Ca2+-independent components of IK based on the time constant of inactivation: a fast, transient outward current, a rapidly activating, slowly inactivating current (Ik1), and a slowly inactivating current (Ik2). Extracellular Cl− differentially affects these components. Because the inactivation time constants of Ik1 and Ik2 are similar to those of Kv1.5 and Kv2.1, we transiently transfected these constructs into CHO cells and found that low extracellular Cl− inhibited both channels with linear current reductions of 0.38%/mM and 0.49%/mM, respectively. We also tested heterologously expressed Slick and Slack conductances, two intracellularly Cl−-sensitive K+ channels, but found no extracellular Cl− sensitivity. The Cl− sensitivity of Kv2.1 and its robust expression within OHCs verified by single-cell RT-PCR indicate that these channels underlie the OHC's extracellular Cl− sensitivity.

Keywords: voltage-dependent potassium ion channels, chloride, outer hair cells

the outer hair cell (OHC) is both a receptor and an effector, possessing a distinct ensemble of membrane proteins, e.g., prestin (54), the α9- and α10-nicotinic ACh receptor subunits (7, 8), and the unidentified transduction channel (5), which underlie these processes.

Concerning the effector role of OHCs, recent studies suggest that prestin activity is highly dependent on intracellular Cl− anions (36, 38, 44, 46). Modulating intracellular Cl− alters the motor's nonlinear charge movement (or nonlinear capacitance), thereby affecting the voltage sensitivity of OHC electromotility. The mechanism whereby anions work on prestin remains controversial; however, much evidence points to an allosteric mechanism (38, 45), similar to the way in which Ca2+ modulate the voltage sensitivity of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels (15, 53).

Concerning the sensory role of the OHC, receptor potentials that drive neurotransmitter release and electromotility are subject to the shaping effects of the cell's basolateral voltage-dependent membrane conductances (17). The dominant conductances of the adult OHC are K+ conductances, with two types having been distinguished based on voltage dependence and pharmacological properties: a K+ current in OHC activated at negative potential (IK,n) and the outward K+ current of the OHC (IK) (16, 27, 42). IK,n is half-activated at −92 mV and likely helps to set the resting membrane potential of the OHC. IK activates more positive to −40 mV. Because this voltage is depolarized sufficiently from the normal in vivo resting potential [approximately −70 mV (6)], it might be expected that only large suprathreshold receptor potentials could activate IK to shape the cell's response (12).

Although the effects of Cl− on prestin result from intracellular interactions with the protein, we have shown that extracellular Cl− can modulate the motor via flux through a tension- and voltage-dependent Cl− conductance, termed GmetL (38, 46). Indeed, manipulation of extracellular perilymphatic Cl− was shown to reversibly and profoundly alter cochlear amplification in vivo (44).

In our quest to study the permeation characteristics of GmetL, we found that extracellular Cl− has an unusual effect on IK in OHCs. Reduction of extracellular Cl− reduces the outward current in a concentration-dependent manner. We find that this effect is due, in part, to a selective action on the inactivation kinetics of the voltage-dependent K+ (Kv) conductance of the OHC alone, with Kv conductances of other inner ear cells being unaffected. The growing impact of anions in the auditory periphery is remarkable.

METHODS

Tissue preparation for electrophysiology.

The experiments were performed in accordance with an approved protocol from Yale University's animal use and care committee. Hartley albino guinea pigs (150–200 g) were anesthetized with halothane, and temporal bones were excised rapidly. The top two turns of the organ of Corti were dissected and incubated for 10–12 min with neutral protease (0.5 mg/ml; Worthington) in a nominally Ca2+-free solution containing (in mM): 140 NaCl and 5 KCl. Subsequently, the tissue was triturated with a glass pipette for ∼1 min with the above solution plus 2 mM Ca2+. Drops of the cell suspension were transferred into a small recording chamber mounted on the stage of a Nikon inverted microscope, and cells (OHCs, Hensen cells, and Deiters' cells) were allowed to settle onto the chamber bottom.

Electrophysiological recording.

Patch-clamp experiments were performed in the whole cell configuration using pipettes pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries. The pipette resistance ranged between 1.5 and 3 MΩ and was <5–10 MΩ after whole cell establishment. Clamp tau values were <100–200 μs, orders of magnitude less than measured current tau values. Pipette solution contained (in mM): 150 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, and 5 HEPES. The absence of Ca2+ intracellularly removes the influence of BK and small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SK) channel conductances. We did not add ATP or other metabolites to the pipette solution so that currents dependent on these metabolites would be eliminated from our evaluations of Cl− effects. The bath solution contained (in mM): 145 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, and 5 HEPES. The use of intra- and extracellular HEPES obviates the potential effect of pH alterations during changes in Cl−. Bath and pipette solutions were adjusted to ∼300 mosmol/kg with dextrose and to pH 7.3. The liquid junction potential was around 1–3 mV with 3 M KCl salt bridges. Whole cell currents were recorded at room temperature using an Axon 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments), Digidata 1321 board (Axon Instruments), and the software program jClamp (Scisoft).

Concentration-response curves were obtained by substituting gluconate for Cl−. Extracellular Cl− concentrations of 5, 30, 70, 100, 125, and 150 mM were tested. Responses were plotted relative to the 150 mM Cl− condition. Currents were averaged from the final 100 ms of a 200-ms test step to +50 mV from a holding potential of −40 mV. Attempts were made to fit the response function to the Hill equation, but fits were inadequate. Instead, data were fit to a linear equation to obtain slopes.

Isolation of individual OHCs for RT-PCR.

Guinea pig temporal bones were dissected in PBS. Turns two to four of the cochleae were mechanically triturated separately in PBS and suspended in petri dishes to allow cells to settle. Silanized pipettes (trimethyl-chlorsilan; Fluka, St. Louis, MO) with a pore diameter of ∼30 μm were used to pick up individual OHCs. Following capture of individual OHCs, the contents of the pipettes were expelled into Eppendorf tubes and stored at −80°C.

Single cell nested PCR from OHC.

cDNAs from each isolated cell were synthesized as previously described (30). Nested PCR was performed in two steps. First, 35 cycles of PCR were run (94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, 68°C for 3 min) using 5 μl of each cDNA and corresponding Kv outer primers. Second, 5 μl of each reaction from the first step were used for another 35 cycles of amplification using Kv inner primers. Both steps used the Expand High Fidelity PCR System (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Fragments were analyzed on 2% agarose resolute GPG gel (American Bioanalytical, Natick, MA). To confirm the presence of a correct Kv channel, the PCR products were purified from the gel using a gel purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and sequenced using the corresponding amplification primers by Yale's Keck sequencing facility. The primers were designed to straddle an intron of at least 1,000 bp. The primers were as follows: Kv1.5 outer, Kv1.5FOT GACACTAGCCGGGAAACAGA and Kv1.5ROT GGTGACCCTTGGTGTTATGG; Kv1.5 inner, Kv1.5FIN TCAAGGCAGACTTGCAACAG and Kv1.5RIN GAAGTTAGAGGGCAGGAGGG; Kv2.1, Kv2.1FOT CAAAAGAAGGAGCAGATGAACGAG and Kv2.1ROT TTGAGTGACAGGGCAATGGTG; Kv4.2 outer, Kv4.2FOT: GCCTTCGTTAGCAAATCTGG and Kv4.2ROT ACACATTGGCATTTGGGATT; Kv4.2 inner, Kv4.2FIN TTCACTGCCTGGAGAAAACC and Kv4.2RIN AGCAAGTGCTGGTGACTCCT; Kv4.3 outer, Kv4.3FOT GGCTACACCCTGAAGAGCTG and Kv4.3ROT AGTTGGTGACTATGACGGGG; and Kv4.3 inner, Kv4.3FIN CATGGCCATCATCATCTTTG and Kv4.3RIN GCCAAATATCTTCCCAGCAA.

To investigate whether the pore residue 356 in Kv2.1 has an effect on extracellular Cl− sensitivity (see results and discussion), K356G mutants were generated using QuickChange II or QuickChange Lightning site-directed mutagenesis kits (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) with rat Kv2.1 as a template. Mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing, including the entire coding region. The following primers were used: Kv2.1K356GF: GATGAGGACGACACCGGGTTCAAAAGCATCCCC and Kv2.1K356GR GGGGATGCTTTTGAACCCGGTGTCGTCCTCATC.

Analysis and statistics.

For current-voltage (I-V) analysis, peak currents at each test potential were measured as the difference between the maximal outward current amplitudes and the zero current level. The waveforms of the 4-AP and Cl−-sensitive currents were determined by subtraction of control currents (recorded in the absence of 4-AP and the presence of 150 mM Cl−). The decay phases of the currents evoked during long (5.0 s) depolarizing voltage steps to test potentials from a holding potential of −80 mV were fitted by a single or the sum of two exponentials using one of the following expressions:

| (1) |

where t is time, τ1 andτ2 are the time constants of decay of the inactivating IK currents, A1 and A2 are the amplitudes of the inactivating current components, and Ass is the amplitude of the steady-state, noninactivating component of the total outward current. In the manuscript, control currents refer to those obtained in the presence of 150 mM extracellular Cl−.

For the steady-state inactivation curve, the current amplitude during each test pulse was normalized to maximal current (I/Imax) and plotted against the voltage during the conditioning prepulse. These data were fitted by a Boltzmann equation:

| (2) |

where V1/2 is the conditioning potential that gives I/Imax = 0.5, Vm is the conditioning potential, and k describes the steepness of the curve.

Data are reported as means ± SE. Statistical significance was calculated using Student's t-test. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (22°C).

RESULTS

IK in OHCs is sensitive to 4-AP and extracellular Cl−.

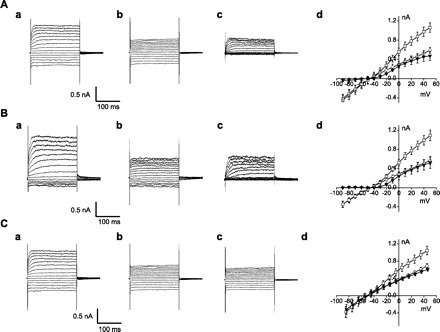

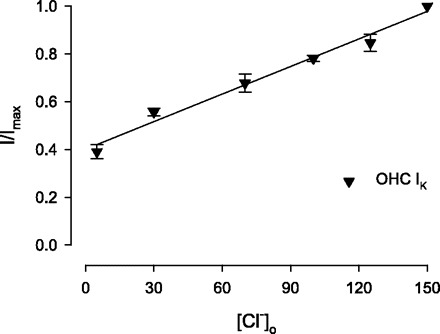

Outward currents were recorded routinely during depolarizing voltage steps to potentials more positive than the holding potential of −40 mV (Fig. 1). At this holding potential, IK,n is not further activated upon depolarization (16), thus allowing study of IK in isolation following linear current subtractions (see discussion for details). These outward currents (IK) did not decay appreciably during the 200-ms voltage steps, as previously observed (16, 27, 42). 4-AP (100 μM) strongly inhibits outward IK in OHCs (Fig. 1A). Surprisingly, however, extracellular Cl− can also modulate IK of OHCs. Switching from a high-Cl− solution to a 5 mM Cl− solution strongly inhibits the outward current (Fig. 1B). The effect was reversible (68.5 ± 16.7% reversibility, n = 3). Comparison of the 100 μM 4-AP and Cl−-sensitive currents indicates that they are similar in two ways: each has similar waveform and reversal potential (−70 mV). An initial perfusion of 100 μM 4-AP can abolish the subsequent effects of 5 mM Cl− on IK (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that Cl− reduction inhibited the same IK current that was specifically blocked by 4-AP. The average (n = 6) dose-response curve for extracellular Cl− on IK was not well fit by a sigmoidal Hill equation. Instead, the K+ current appeared linear with Cl− concentration, with a dependence of 0.4%/mM (Fig. 2). This type of behavior may be related to actions on surface charges at the pore of channels (20) and is further explored below. Changes in intracellular Cl− were ineffective (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of outward K+ current of the outer hair cells (IK) by 4-AP and low extracellular Cl−. Membrane current was recorded with 200-ms pulses to potentials between −90 and 50 mV from a holding potential of −40 mV. The waveforms of the 4-AP- and Cl−-sensitive currents were determined by subtraction of control currents. A: a, control; b, 100 μM 4-AP; c, 100 μM 4-AP-sensitive current; d, current-voltage relationship of IK for control (□), 100 μM 4-AP (○), and 100 μM 4-AP-sensitive current (▾) (n = 3). B: a, control; b, 5 mM Cl−; c, 5 mM Cl−-sensitive current; d, current-voltage relationship of IK for control (□), 5 mM Cl− (○) and 5 mM Cl−-sensitive current (▾) (n = 5). C: a, control; b, 100 μM 4-AP; c, 100 μM 4-AP + 5 mM Cl−; d, current-voltage relationship of IK for control (□), 100 μM 4-AP (◊), and 100 μM 4-AP + 5 mM Cl− (▾) (n = 3).

Fig. 2.

Concentration-response curve of external Cl− on magnitude of IK. Functions were obtained by substituting gluconate for Cl−. A linear fit (solid line) indicates an IK change of 0.4%/mM Cl−. I/Imax, the current amplitude during each test pulse normalized to maximal current; [Cl−]o, extracellular Cl− concentration; OHC, outer hair cells.

IK of supporting cells is not sensitive to extracellular Cl−.

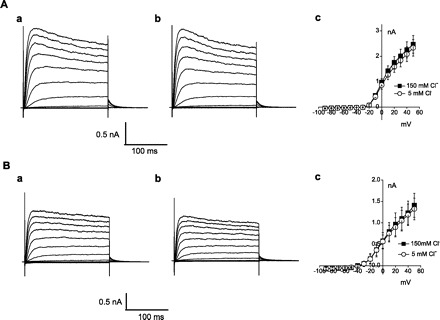

Prominent depolarization-activated outward K+ currents (IK) are recorded from supporting cells, such as Deiters' and Hensen cells (31, 40, 41, 47). We tested to determine whether these currents were also Cl− sensitive. Figure 3A shows the macroscopic current from a Deiters' cell. Similar to the OHC, there is a rapid activation and slow inactivation elicited by depolarized potentials. For control Cl− conditions, the peak amplitude was 2.47 ± 0.35 nA at +50 mV, and it was 2.33 ± 0.32 nA when extracellular Cl− was reduced to 5 mM (n = 3, P > 0.05). The average I-V curve indicates no significant difference between the two conditions. A similar outward current was elicited from Hensen cells (Fig. 3B). The peak amplitude of the control was 1.41 ± 0.28 nA at +50 mV, and it was 1.32 ± 0.25 nA with 5 mM Cl− (n = 4, P > 0.05). Again, the average I-V curve indicates no differences. We conclude that the IK current of supporting cells is not sensitive to extracellular Cl− changes.

Fig. 3.

Deiters' and Hensen cell K+ currents are insensitive to extracellular Cl−. Current traces obtained with 500-ms steps from −90 to 50 mV from a −40-mV holding potential. A: a, 150 mM Cl− control current of Deiters' cell; b, 5 mM Cl−; c, current-voltage relationship of IK of Deiters' cell for control (■) and 5 mM Cl− (○). B: a, 150 mM Cl− control current of Hensen cell; b, 5 mM Cl−; c, current-voltage relationship of IK in Hensen cell for control (■) and 5 mM Cl− (○).

Slick and slack channels are not sensitive to extracellular Cl−.

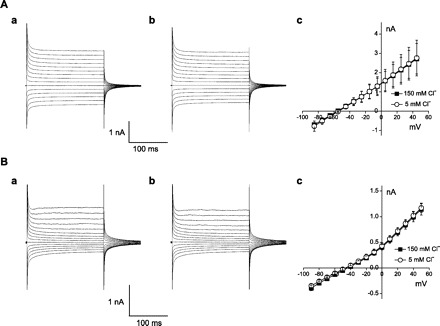

The molecular identity of outward IK in the OHC is not clear. It is known that the sodium-activated K+ channels Slick (Slo2.1) and Slack (Slo2.2), which are prominent in brain stem auditory pathways, are sensitive to intracellular Cl−, but it is not known whether those channels are also sensitive to extracellular Cl− (2) (Kaczmarek, personal communication). Whole cell recording of transfected cells was employed to examine the sensitivity of Slick and Slack currents to extracellular Cl−. Figure 4A shows Slack whole cell currents. The last 50-ms average current amplitude was 2.72 ± 0.79 nA at +50 mV (Fig. 4Aa). Upon changing extracellular Cl− from 150 to 5 mM, the current amplitude was 2.76 ± 0.93 nA and was not different from control (n = 4, P > 0.05, Fig. 4Ab). The last 50-ms average current amplitude of Slick was 1.14 ± 0.11 nA at +50 mV (Fig. 4Ba). Upon changing extracellular Cl− from 150 to 5 mM, the current amplitude was 1.17 ± 0.09 nA and was not different from control (n = 4, P > 0.05, Fig. 4Bb). These results show that Slick and Slack channels are not sensitive to extracellular Cl−, indicating that they do not underlie OHC IK.

Fig. 4.

Slack and Slick channel currents are insensitive to extracellular Cl−. A: a, control current of Slack-transfected cell; b, 5 mM Cl−; c, current-voltage relationship of Slack for control (■) and 5 mM Cl− (○). B: a, control current of Slick-transfected cell; b, 5 mM Cl−; c, current-voltage relationship of Slick for control (■) and 5 mM Cl− (○).

Three components in outward IK.

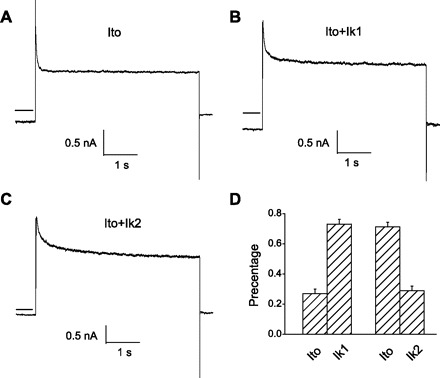

Outward K+ currents in other tissues have been characterized in terms of kinetic components (52). To further study the mechanism of inhibition by Cl− on IK of the OHC, we performed a similar analysis. Currents were elicited by a 5-s depolarizing step to a potential of +40 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV. Outward K+ currents in all cells activated rapidly, and the decay phases of the currents were somewhat variable among cells (Table 1 and Fig. 5). One group of cells exhibited only a single exponential decay phase, termed Ito (Fig. 5A). We used a dual exponential fit (see methods) for two additional populations of cells that each possessed the very fast component (Ito) and one of two additional slower second components, termed Ik1 and Ik2 (Fig. 5, B and C). Thus exponential fits revealed three inactivating components with decay time constants of 78.4 ± 6.3 ms (n = 5), 685.4 ± 61.3 ms (n = 10), and 1,504.4 ± 104.6 ms (n = 10), corresponding to Ito, Ik1, and Ik2, respectively. Of the cells studied, 14.3% had Ito alone, 48.6% had Ito and Ik1, and 37.1% had Ito and Ik2. The variance in the second term fits of each population was quite small and validates our initial separation into two second component populations. Figure 5D plots the relative distribution of the different current components, and Table 1 summarizes the data. Subsequent experiments were focused on characterizing the Cl− sensitivity of these depolarization-activated K+ current components.

Table 1.

Three distinct outward potassium currents in guinea pig outer hair cells

| Ito | Ik1 | Ik2 | Iss | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ito (n = 5) | ||||

| τdecay, ms | 64.8 ± 12.7 | |||

| Ipeak, % | 49.3 ± 7.0 | 50.7 ± 7.0 | ||

| Ito + Ik1 (n = 10) | ||||

| τdecay, ms | 78.4 ± 6.3 | 685.4 ± 61.3 | ||

| Ipeak, % | 36.5 ± 2.7 | 10.0 ± 1.1 | 53.4 ± 2.4 | |

| Ito + Ik2 (n = 10) | ||||

| τdecay, ms | 90.5 ± 5.4 | 1,504.4 ± 104.6 | ||

| Ipeak, % | 31.3 ± 2.2 | 12.0 ± 0.9 | 56.7 ± 2.7 |

All values are means ± SE; n, no. of experiments. Ito, transient outward K+ currents; Ik1, K+ currents of slow component 1; Ik2, K+ currents of slow component 2; Iss, steady-state currents. Currents were determined from analyses of records obtained on depolarization to +40 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV.

Fig. 5.

Three kinetic components of outer hair cell (OHC) outward IK are identified. Cells were held at −80 mV and stepped up to +40 mV for 5 s. A: only fast component, transient outward K+ current (Ito). B: Ito + Ik1 (K+ current of slow component 1) components. C: Ito + Ik2 (K+ current of slow component 2) components. D: the ratio of different components of IK. Horizontal solid lines on left of traces depict zero current levels.

Cl− affects components of IK in different ways.

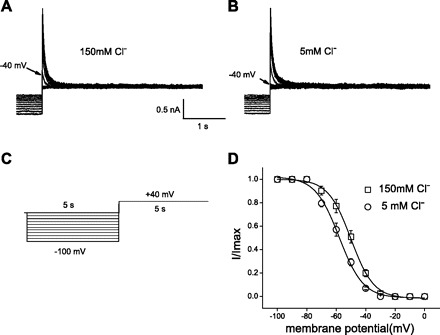

The voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation of Ito was examined using depolarizing voltage steps to +40 mV following 5-s conditioning prepulses to potentials between −100 and 0 mV (Fig. 6); the protocol is shown below the current records in Fig. 6C. Such robust inactivation of the outward IK in OHCs has never been observed before, simply because such long-duration protocols have never been used. The amplitudes of Ito during each test pulse to +40 mV were measured as the difference between peak outward current and the current remaining at the end of the depolarizing pulse [steady-state current (Iss)]. The amplitudes of Ito evoked from each conditioning potential were then normalized to maximal current amplitudes (in the same cell). For example, in the control condition (Fig. 6A), the amplitude of the peak current at the conditioning potential of −40 mV was 0.219 nA. When extracellular Cl− was changed from 150 to 5 mM, the amplitude was reduced to 0.059 nA (Fig. 6B). The mean ± SE normalized Ito amplitudes are plotted as a function of conditioning potential in Fig. 6D; the continuous lines represent the best Boltzmann fits to the averaged data. The steady-state inactivation data for Ito in 150 mM Cl− are well described by a single Boltzmann with a V1/2 of −50 mV. Reducing extracellular Cl− caused the inactivation curve of Ito to shift to the left (Fig. 6D), with 5 mM Cl− producing an 8-mV hyperpolarizing shift.

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of Ito by external Cl−. A and B: measurement of voltage dependence of inactivation. Superimposed current records during conditioning pulses and subsequent test pulses to +40 mV for control 150 mM Cl− (A) and 5 mM Cl− (B). Arrows indicate test current level at prepulse potential of −40 mV. C: protocol for inactivation curve: 5-s conditioning prepulses to various potentials (from −100 to 0 mV in 10-mV increments) were followed by a 5-s test pulse to +40 mV. Holding potential was −80 mV. D: mean ± SE; n = 4. Steady-state inactivation curves of Ito. Ito during each test pulse was normalized to maximal Ito (I/Imax) and plotted against conditioning prepulse potential. Data are fitted with a Boltzmann equation.

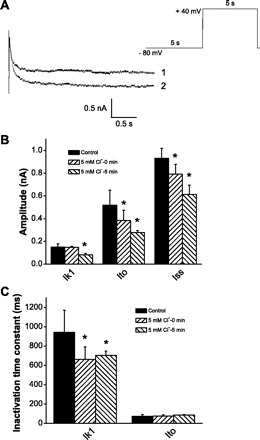

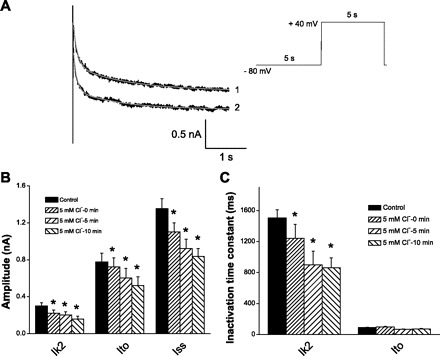

Because we have no specific blockers for the identified kinetic components of Ik1, an analysis of the two additional components was performed by fitting two exponential functions to determine the amplitude and inactivation time constant of each component, Ik1 and Ik2. The effects of Cl− were analyzed with the simplified voltage protocol depicted in Figs. 7 and 8. In Figs. 7A and 8A, depolarization-induced outward currents are depicted before (traces on top) and after (traces on bottom) switching to 5 mM Cl−. The bar plots in Figs. 7 and 8 show that, while the time constant of Ito remained unaffected, the magnitudes of all components decreased, and the inactivation time constants of Ik1 and Ik2 shortened. The inhibitory effect of Cl− was time dependent on the scale of minutes. From these analyses, we conclude that lowering extracellular Cl− inhibited IK in OHCs by shifting the inactivation curve to the left and/or reducing the current amplitude.

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of Ik1 by external Cl−. A: superimposed pairs of currents at +40 mV recorded following conditioning pulses (−80 mV) for control 150 mM Cl− (trace 1) and 5 mM Cl− (trace 2). Red solid lines represent exponential fitting. Stimulation protocol is depicted at top right. B: time-dependent inhibition of current amplitude of Ik1, Ito, and steady-state current (Iss). C: time-dependent inhibition of inactivation time constant of Ik1 by external Cl−. *Significance at the 0.05 level.

Fig. 8.

Inhibition of Ik2 by external Cl−. A: superimposed pairs of currents at +40 mV recorded following conditioning pulses (−80 mV) for control 150 mM Cl− (trace 1) and 5 mM Cl− (trace 2). Red solid lines represent exponential fitting. Stimulation protocol is depicted at top right. B: time-dependent inhibition on current amplitude of Ik2, Ito, and Iss. C: time-dependent inhibition of inactivation time constant of Ik2 by external Cl−. *Significance at the 0.05 level.

Extracellular Cl− inhibits Kv1.5 and Kv2.1 in CHO cells.

The inactivation time constants of Ik1 and Ik2 are similar to those of the cardiac current in atrial myocytes that activates ultrarapidly but with no inactivation (Ikur) and the delayed-rectifier K+ current in myocytes that slowly activates and deactivates, with a single channel conductance of 3–5 pS (Ik,slow), respectively (33, 34, 52). Kv1.5 and Kv2.1 contribute to Ikur and Ik,slow. To determine whether these subtypes contribute to OHC IK, we transiently transfected Kv1.5 and Kv2.1 into CHO cells and tested the Cl− sensitivity of the channels. Control macroscopic current of Kv1.5 is depicted in Fig. 9A, where peak amplitude at +50 mV is 3.65 ± 0.13 nA (n = 4). A switch to 5 mM extracellular Cl− reduced the current amplitude to 2.00 ± 0.11 nA (Fig. 9B). Similar results were found with Kv2.1. In the control condition (Fig. 9C), the current amplitude is 8.52 ± 1.87 nA, and it is reduced to 6.15 ± 1.35 nA following the switch to 5 mM extracellular Cl− (n = 3, Fig. 9D). Similar to OHC IK, the dependence of Kv1.5 and Kv2.1 currents on extracellular Cl− was not fit well by a sigmoidal Hill equation. Linear regression fits gave 0.38%/mM (n = 6) and 0.49%/mM (n = 5), respectively (Fig. 9E), similar to results in OHCs.

Fig. 9.

Extracellular Cl− inhibited voltage-dependent K+ (Kv) 1.5 and Kv2.1 in transfected CHO cells. A: whole cell current of Kv1.5 in 150 mM Cl−. B: 5 mM Cl− inhibited the Kv1.5 current. C: whole cell current of Kv2.1 in 150 mM Cl−. D: 5 mM Cl− inhibited the Kv2.1 current. E: concentration-response curve of external Cl− on magnitude of Kv1.5 and Kv2.1.

Kv2.1 and Kv1.5 as well as Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 are expressed in guniea pig OHCs.

We sought to determine whether these Kv channels that have properties of the Cl−-sensitive channel(s) in the OHC are actually present in OHCs. We opted to use a single-cell RT-PCR strategy using primers that spanned introns to ascertain the presence of transcripts encoding Kv1.5 and Kv2.1 channels in the OHC. For comparison, we also tested for Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 transcripts. OHCs were isolated from different turns of the cochlea, and cDNA was made from these individual cells. Single-cell PCR amplifications were done, and the PCR products of the expected size were isolated and sequenced to confirm their identity. As shown in Fig. 10, Kv 2.1 was present in all nine OHCs and was detected after one round of amplification. In contrast, Kv1.5, Kv4.2, and Kv4.3 required two rounds of nested PCR amplification to be detected. Taken together, these data indicate that these channels are present in OHCs, with Kv2.1 predominating, and likely are responsible for its sensitivity to extracellular Cl−.

Fig. 10.

Kv2.1, Kv1.5, Kv4.2, and Kv4.3 are present in guinea pig OHCs by single-cell RT-PCR. The figure shows single-cell PCR of individual Kv channels. Nine individual OHC were isolated as described in the methods, and cDNA was synthesized using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Superscript II). A fixed amount of cDNA from these cells was then used as template for amplifying Kv channels. The PCR products were separated on a 2% agarose gel, and the products were detected by ethidium bromide staining. Kv2.1 was present in all the cells and was detected after one round of amplification (35 cycles). In contrast, Kv1.5, Kv4.2, and Kv4.3 were present in only a fraction of cells and required two rounds of nested amplification. The amplification products of each Kv channel are shown in sequence (Kv1.5, Kv2.1, Kv4.2, and Kv4.3 from top to bottom). PCR products from individual cells from turns 2–4 are aligned. We analyzed three cells from each turn. The correct PCR product is indicated by an arrow and was confirmed by sequencing. Also shown are the negative controls and 1-kb markers (lanes 10 and 11, respectively).

Because the Cl− dependence of these channels is linear, and such behavior may arise from charge screening effects at the mouth of channels (20), we investigated the mutation of residue K356G at the mouth of the Kv2.1 channel. This mutation has been shown to alter channel conductance by interfering with a K+-selective interaction with that site (4). We speculated that Cl− might be modulating this interaction. However, no statistical difference was observed in the ability of low Cl− to reduce K+ currents [IK 5/150 mM Cl−: 0.521±0.089 for WT (n = 8); 0.387±0.059 for K356G (n = 12); P > 0.05].

DISCUSSION

There are two major voltage-dependent K+ currents in OHC, IK,n and IK, whose pharmacological sensitivities have been well studied (16, 27, 42). Both conductances are largely restricted to the basal pole of the OHC (43). Despite this wealth of knowledge, much remains to be learned about these channels; for example, we have recently shown that capsaicin can block OHC outward IK and IK,n (51). The molecular entity underlying IK,n is believed to comprise KCNQ4 subunits (3, 14, 28). On the other hand, the molecular identity of IK has not been suggested previously. In the present work, we identify IK as a current sensitive to extracellular Cl− and utilize this sensitivity and its kinetics to hone in on its molecular identity.

Sensitivity of OHC IK to extracellular Cl− and its significance.

We found that OHC IK, but neither IK of Deiters nor Hensen cells, is decreased by reduction of extracellular Cl− with a sensitivity of 0.4%/mM, indicating a significant sensitivity to Cl− change over a wide range of extracellular levels. It is not known whether physiological fluctuations of Cl− occur that could significantly modulate IK. However, it may be possible that the restricted extracellular space between the Dieters cell and OHC base, where OHC voltage-dependent conductances reside (43), could support functionally significant fluctuations in ion concentrations, in the face of small transmembrane ion fluxes. Such a scenario is well established for intracellular compartmentalization (35).

To estimate the Cl− concentration change made by a small flux of Cl− ions at the base of the OHC, we assessed the volume within which Cl− concentration may change from published electron microscopy descriptions (9, 22, 29, 39). As an example, we evaluate a typical mature OHC in the apical region, which has a diameter of ∼7 μm. The distance from just above the nucleus to the bottom round end of the OHC, where most of the Kv channels concentrate (43), is ∼13 μm. This region resides in the cup formed by the Deiters' cell. An average of 15 afferent nerve terminals and 8 efferent terminals form close contact with the OHC (and with each other) through specialized synaptic structures, with a rather uniform gap of 0.04 μm. This gap is similar to the reported intercellular space between the type I hair cell and its calyx ending in the vestibular system (10, 11). We assume a cylindrical OHC with hemispherical base and a Dieters' cell cup shaped like an inverted cone, whose height is 8.5 μm and base diameter the same as the OHCs. Next, the minimal volume in which the Kv channels can “see” a Cl− fluctuation is the above-mentioned gap region, which is ∼11 μm3. If we assume the Kv channels have access to the whole cup region (no nerve ending present), then that volume is ∼27 μm3. Next, we estimate the Cl− flux. One typical Cl− channel with 25 pS conductance releases ∼106 Cl− ions per second around resting potential (−60 mV). That translates into a 1.5 mM Cl− concentration change in the minimal volume and 0.6 mM Cl− concentration change in the maximal volume. If there are 10 Cl− channels open simultaneously for 1 s, Kv channels will see anywhere between 6 and 15 mM Cl− concentration change, which translates to 2.4–6% change in K+ current magnitude. Specific ion accumulation in a very restricted space has been proposed to influence synaptic transmission, as reported recently in a very detailed work by Lim and colleagues (23) in their study of K+ accumulation between type I hair cells and calyx terminals in mouse crista. They found that responses to a depolarizing voltage step in embedded, but not isolated, hair cells resulted in a >40-mV shift of the K+ equilibrium potential and a rise in effective K+ concentration of >50 mM in the intercellular space. These results strengthen our predictions for extracellular Cl− fluctuation at the OHC/Deiters' cell interface.

The existence of the GABAergic efferent synapse at the basal pole, with associated conductances and transporters, could contribute to such fluctuations in local Cl− levels (25). Although the demonstration of functional GABA effects on isolated OHCs has been variable (possibly because of inappropriate pipette Cl− levels; see Ref. 44), recent knockout experiments clearly establish the efferent receptor's importance (26). Interestingly, an involvement of Cl− in the efferent response of vestibular hair cells has been proposed, and one of the suggested mechanisms was a Cl− dependence of the SK conductance known to be activated subsequent to ACh application (13). Perhaps efferent effects in the mammalian cochlea somehow involve Cl− modulation of IK; in this case, the voltage activation range of the conductance would indicate that effects may only occur at suprathreshold acoustic levels where large receptor potentials could activate IK (6, 12). Such suprathreshold GABAergic effects may not be observable by standard measures of efferent activity (26).

We have recently found that manipulations of perilymphatic Cl− can impact on prestin-dependent cochlear amplification on the basilar membrane near threshold and concluded that intracellular Cl− was being modified via the activity of GmetL, an OHC lateral membrane conductance for Cl− (44). Could IK modulation have played a role in those Cl− effects? It is unlikely since, in that study, other agents, including salicylate and tributyltin (a Cl− ionophore), were effective in the presence of normal, unperturbed extracellular Cl−. Additionally, it has been shown that 4-AP, which blocks IK, does not interfere with threshold cochlear function when perfused via perilymph (18).

Could BK or IK,n OHC conductances have contributed to the Cl−-sensitive IK that we identify?

BK or Ca2+-activated K+ channel has been measured in OHCs (e.g., see Ref. 49) and potentially could contribute to the Cl−-sensitive K+ conductance that we identify. However, we think this is not the case, based on several observations. First, full rundown of Ca2+ current (ICa), which may supply Ca2+ for BK activation, likely has occurred in our cells, since this is known to happen in guinea pig OHCs whether or not ATP or GTP is included in the patch pipette (24). Thus, given the very low intracellular Ca2+ that we have intracellularly (estimated to be <1 nM) and the classic sensitivity of BK to Ca2+ (1), BK cannot significantly contribute to our measured IK. Indeed, Wersinger et al. (49), even with a very high Ca2+ pipette solution, observed insignificant BK current (iberiotoxin sensitive) in apical OHC.

IK,n is a major conductance near the resting potential of OHCs and potentially could have contributed to our measures. We think not, however, based on several observations. Housley and Ashmore (16) showed that resting OHC conductance varies with the length of the cell, decreasing dramatically with increases in length; consequently, IK,n is expected to be quite small compared with IK in our long OHC population from low-frequency regions. Indeed, in this population, we previously found that IK,n is not observable in about one-half of the cells (43). Nenov et al. (32) confirmed the above observations. Thus, we expect that relative contamination of the IK we measure by IK,n will be small. Interestingly, Wersinger et al. (49) found that linoperdine at 100–200 μM was able to substantially block outward K+ currents in apical OHCs and suggested that KCNQ4 channels underlie the major component of the outward IK. It must be emphasized, however, that this drug will block both Kv2.1 [IC30 ∼100 μM (50)] and Kv4.3 [IC50 86 μM (48)], two channels we find transcripts for in OHCs.

Two other factors lead us to dismiss substantial KCNQ4 contributions to our measurements. Our holding protocol at −40 mV ensures that IK,n is fully activated, with no further activation upon depolarizations that we used to evoke IK. Thus, similar to IK,L in vestibular type 1 hair cells [a conductance analogous to IK,n (37)], when depolarized from potentials where the conductance is fully activated, time-independent, instantaneous currents result and consequently are amenable to simple current subtractions that expose embedded voltage- and time-dependent currents. Thus, the time- and voltage-dependent Cl−-sensitive current, IK, is readily isolated from KCNQ4 contributions. Of course, we cannot dismiss that KCNQ4 channels are Cl− sensitive, since our methods do not permit this evaluation. We would have to block IK independently, and observe Cl− effects on IK,n. Such sensitivity, if it exists, would be very significant.

How might Cl− alter IK?

The linear dependence of IK on extracellular Cl− concentration may indicate that fixed charges at the mouth of the channel are screened, thereby altering the local concentration of K+ available for permeation (20) or interfering with K+-specific interactions with the channel. It has been established that residue K356 at the extracellular mouth of Kv2.1 significantly controls K+ permeation by interacting with K+ (4), and we reasoned that this residue might be the target of Cl−. However, we found that mutations of this residue were without effect on Cl− sensitivity, possibly indicating that other charged residues underlie Cl− sensitivity.

Molecular substrate of IK.

The K+ channels Slick and Slack, which are highly expressed in central auditory neurons, are known to be sensitive to internal Cl− (2) but had not been tested for extracellular Cl− sensitivity. Here we show that they are unaffected by changes in extracellular Cl− and therefore do not underlie OHC IK.

To identify other molecular candidates of channels contributing to OHC IK, we characterized the differing temporal components of IK, as has been done previously (52). The distinct inactivation time constants of Ik1 and Ik2 are similar to those of Ikur and Ik,slow found in cardiac myocytes (33, 34, 52), and it is believed that Kv1.5 and Kv2.1 contribute to Ikur and Ik,slow. Our experiments revealed that these two channels, when expressed in CHO cells, have extracellular Cl− sensitivity similar to that in the native OHC. This result and similar channel blocker sensitivities between these channels and OHC IK (24, 32, 42) led us to undertake verification of the channels' presence in OHCs. Our PCR amplification data suggest that Kv2.1 was the predominant form of Kv channel present in the OHC. Transcripts encoding this channel were present in all OHCs tested and moreover required only one round of amplification for detection. In contrast, Kv1.5 required two rounds of amplification and was present in only one cell of nine tested.

Extracellular Cl− modulates the transient outward K+ current (Ito) in rat ventricular myocytes (19, 21). Replacement of Cl− with gluconate resulted in a leftward shift (−12 mV) of the steady-state inactivation curve (19), which was comparable to an OHC IK shift of −8 mV. Interestingly, both Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 contribute to cardiac Ito, and, although we did not have these constructs available to us to test for Cl− effects, we did detect transcripts for these channels in OHCs with RT-PCR, indicating that they may contribute to the Cl−-sensitive IK of OHCs.

Although expression level differences by PCR amplification in single cells may be difficult to quantify, the differences in detectability using PCR amplification between Kv2.1 and the other channels were extreme. The presence of the Kv2.1 transcript in all single cells tested, its detection with only one round of amplification, and the channel's similar Cl− sensitivity compared with that of OHC IK strongly suggest that Kv2.1 is the dominant contributor to the Cl−-dependent IK in OHCs.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant DC-00273 to J. Santos-Sacchi.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Len Kaczmarek for providing Kv channel plasmids and Dr. Lei Song for isolating OHCs for single cell PCR.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ashmore JF, Meech RW. Ionic basis of membrane potential in outer hair cells of guinea pig cochlea. Nature 322: 368–371, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bhattacharjee A, Kaczmarek LK. For K+ channels, Na+ is the new Ca2+. Trends Neurosci 28: 422–428, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chambard JM, Ashmore JF. Regulation of the voltage-gated potassium channel KCNQ4 in the auditory pathway. Pflugers Arch 450: 34–44, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Consiglio JF, Andalib P, Korn SJ. Influence of pore residues on permeation properties in the Kv2.1 potassium channel Evidence for a selective functional interaction of K+ with the outer vestibule. J Gen Physiol 121: 111–124, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Corey DP. What is the hair cell transduction channel? J Physiol 576: 23–28, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dallos P, Santos-Sacchi J, Flock A. Intracellular recordings from cochlear outer hair cells. Science 218: 582–584, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Elgoyhen AB, Johnson DS, Boulter J, Vetter DE, Heinemann S. Alpha 9: an acetylcholine receptor with novel pharmacological properties expressed in rat cochlear hair cells. Cell 79: 705–715, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elgoyhen AB, Vetter DE, Katz E, Rothlin CV, Heinemann SF, Boulter J. alpha10: a determinant of nicotinic cholinergic receptor function in mammalian vestibular and cochlear mechanosensory hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 3501–3506, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Furness DN, Hulme JA, Lawton DM, Hackney CM. Distribution of the glutamate/aspartate transporter GLAST in relation to the afferent synapses of outer hair cells in the guinea pig cochlea. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 3: 234–247, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goldberg JM. Theoretical analysis of intercellular communication between the vestibular type I hair cell and its calyx ending. J Neurophysiol 76: 1942–1957, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gulley RL, Bagger-Sjoback D. Freeze-fracture studies on the synapse between the type I hair cell and the calyceal terminal in the guinea-pig vestibular system. J Neurocytol 8: 591–603, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. He DZZ, Jia SP, Dallos P. Mechanoelectrical transduction of adult outer hair cells studied in a gerbil hemicochlea. Nature 429: 766–770, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holt JC, Pantoja AM, Athas GB, Guth PS. A role for chloride in the hyperpolarizing effect of acetylcholine in isolated frog vestibular hair cells. Hear Res 146: 17–27, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Holt JR, Stauffer EA, Abraham D, Geleoc GS. Dominant-negative inhibition of M-like potassium conductances in hair cells of the mouse inner ear. J Neurosci 27: 8940–51, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Horrigan FT, Aldrich RW. Coupling between voltage sensor activation, Ca2+ binding and channel opening in large conductance (BK) potassium channels. J Gen Physiol 120: 267–305, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Housley GD, Ashmore JF. Ionic currents of outer hair cells isolated from the guinea-pig cochlea. J Physiol (Lond) 448: 73–98, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Housley GD, Marcotti W, Navaratnam D, Yamoah EN. Hair cells–beyond the transducer. J Membr Biol 209: 89–118, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kirk DL. Effects of 4-aminopyridine on electrically evoked cochlear emissions and mechano-transduction in guinea pig outer hair cells. Hear Res 161: 99–112, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lai XG, Yang J, Zhou SS, Zhu J, Li GR, Wong TM. Involvement of anion channel(s) in the modulation of the transient outward K+ channel in rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287: C163–C170, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Latorre R, Labarca P, Naranjo D. Surface charge effects on ion conduction in ion channels. Methods Enzymol 207: 471–501, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lefevre T, Lefevre IA, Coulombe A, Coraboeuf E. Effects of chloride ion substitutes and chloride channel blockers on the transient outward current in rat ventricular myocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1273: 31–43, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liberman MC, Dodds LW, Pierce S. Afferent and efferent innervation of the cat cochlea: quantitative analysis with light and electron microscopy. J Comp Neurol 301: 443–460, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lim R, Kindig AE, Donne SW, Callister RJ, Brichta AM. Potassium accumulation between type I hair cells and calyx terminals in mouse crista. Exp Brain Res 210: 607–621, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin X, Hume RI, Nuttall AL. Dihydropyridines and verapamil inhibit voltage-dependent K+ current in isolated outer hair cells of the guinea pig. Hear Res 88: 36–46, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Maison SF, Adams JC, Liberman MC. Olivocochlear innervation in the mouse: immunocytochemical maps, crossed versus uncrossed contributions, and transmitter colocalization. J Comp Neurol 455: 406–416, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maison SF, Rosahl TW, Homanics GE, Liberman MC. Functional role of GABAergic innervation of the cochlea: phenotypic analysis of mice lacking GABA(A) receptor subunits alpha 1, alpha 2, alpha 5, alpha 6, beta 2, beta 3, or delta. J Neurosci 26: 10315–10326, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mammano F, Ashmore JF. Differential expression of outer hair cell potassium currents in the isolated cochlea of the guinea-pig. J Physiol 496: 639–646, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marcotti W, Kros CJ. Developmental expression of the potassium current IK,n contributes to maturation of mouse outer hair cells. J Physiol 520: 653–660, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nadol JB., Jr Synaptic morphology of inner and outer hair cells of the human organ of Corti. J Electron Microsc Tech 15: 187–196, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Navaratnam DS, Bell TJ, Tu TD, Cohen EL, Oberholtzer JC. Differential distribution of Ca2+-activated K+ channel splice variants among hair cells along the tonotopic axis of the chick cochlea. Neuron 19: 1077–1085, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nenov AP, Chen C, Bobbin RP. Outward rectifying potassium currents are the dominant voltage activated currents present in Deiters' cells. Hear Res 123: 168–182, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nenov AP, Norris C, Bobbin RP. Outwardly rectifying currents in guinea pig outer hair cells. Hear Res 105: 146–158, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nerbonne JM, Guo W. Heterogeneous expression of voltage-gated potassium channels in the heart: roles in normal excitation and arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 13: 406–409, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nerbonne JM, Nichols CG, Schwarz TL, Escande D. Genetic manipulation of cardiac K(+) channel function in mice: what have we learned, and where do we go from here? Circ Res 89: 944–956, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Niggli E, Lipp P. Subcellular restricted spaces: significance for cell signalling and excitation-contraction coupling. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 14: 288–291, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Oliver D, He DZ, Klocker N, Ludwig J, Schulte U, Waldegger S, Ruppersberg JP, Dallos P, Fakler B. Intracellular anions as the voltage sensor of prestin, the outer hair cell motor protein. Science 292: 2340–2343, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rusch A, Eatock RA. A delayed rectifier conductance in type I hair cells of the mouse utricle. J Neurophysiol 76: 995–1004, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rybalchenko V, Santos-Sacchi J. Cl− flux through a non-selective, stretch-sensitive conductance influences the outer hair cell motor of the guinea-pig. J Physiol 547: 873–891, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Saito K. Freeze-fracture organization of hair cell synapses in the sensory epithelium of Guinea pig organ of Corti. J Electron Microscopy Techniques 15: 173–186, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Santos-Sacchi J. Asymmetry in voltage-dependent movements of isolated outer hair cells from the organ of Corti. J Neurosci 9: 2954–2962, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Santos-Sacchi J. Isolated supporting cells from the organ of Corti: some whole cell electrical characteristics and estimates of gap junctional conductance. Hear Res 52: 89–98, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Santos-Sacchi J, Dilger JP. Whole cell currents and mechanical responses of isolated outer hair cells. Hear Res 35: 143–150, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Santos-Sacchi J, Huang GJ, Wu M. Mapping the distribution of outer hair cell voltage-dependent conductances by electrical amputation. Biophys J 73: 1424–1429, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Santos-Sacchi J, Song L, Zheng J, Nuttall AL. Control of mammalian cochlear amplification by chloride anions. J Neurosci 26: 3992–3998, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Song L, Santos-Sacchi J. Conformational state-dependent anion binding in prestin: evidence for allosteric modulation. Biophys J 98: 371–376, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Song L, Seeger A, Santos-Sacchi J. On membrane motor activity and chloride flux in the outer hair cell: lessons learned from the environmental toxin tributyltin. Biophys J 88: 2350–2362, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Szucs A, Somodi S, Batta TJ, Toth A, Szigeti GP, Csernoch L, Panyi G, Sziklai I. Differential expression of potassium currents in Deiters cells of the guinea pig cochlea. Pflugers Arch 452: 332–341, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang HS, Pan Z, Shi W, Brown BS, Wymore RS, Cohen IS, Dixon JE, McKinnon D. KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 potassium channel subunits: molecular correlates of the M-channel. Science 282: 1890–1893, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wersinger E, McLean WJ, Fuchs PA, Pyott SJ. BK channels mediate cholinergic inhibition of high frequency cochlear hair cells. PLoS One 5: e13836, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wladyka CL, Kunze DL. KCNQ/M-currents contribute to the resting membrane potential in rat visceral sensory neurons. J Physiol 575: 175–189, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wu T, Song L, Shi X, Jiang Z, Santos-Sacchi J, Nuttall AL. Effect of capsaicin on potassium conductance and electromotility of the guinea pig outer hair cell. Hear Res 272: 117–124, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Xu H, Guo W, Nerbonne JM. Four kinetically distinct depolarization-activated K+ currents in adult mouse ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol 113: 661–678, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhang X, Solaro CR, Lingle CJ. Allosteric regulation of BK channel gating by Ca(2+) and Mg(2+) through a nonselective, low affinity divalent cation site. J Gen Physiol 118: 607–636, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zheng J, Shen W, He DZ, Long KB, Madison LD, Dallos P. Prestin is the motor protein of cochlear outer hair cells. Nature 405: 149–155, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]