Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Epirubicin can induce intracellular reactive oxygen species and is widely used to treat unresectable HCC. Progesterone has been found to inhibit the proliferation of hepatoma cells. This study was designed to test the combined effects of epirubicin and progesterone on human hepatoma cell line, HA22T/VGH. These cells were treated with different concentrations of epirubicin with or without the coaddition of 30 μM progesterone and then analyzed for apoptosis, autophagy, and expressions of apoptotic-related proteins and multidrug-resistant gene. Epirubicin treatment dose-dependently inhibited the growth of HA22T/VGH cells. Addition of 30 μM progesterone, which was inactive alone, augmented the effect of epirubicin on the inhibition of growth of HA22T/VGH cells. Cotreatment with progesterone enhanced epirubicin-induced apoptosis, as evidenced by greater increase in caspase-3 activity and in the ratio of the apoptosis-regulating protein, Bax/Bcl-XL. The combination also caused a decrease in autophagy and in the expression of multidrug resistance-related protein 1 mRNA compared to epirubicin alone. This study shows the epirubicin/progesterone combination was more effective in increasing apoptosis and inversely decreasing autophagy on HA22T/VGH cells treated with epirubicin alone, suggesting that this combination can potentially be used to treat HCC.

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer in men and the seventh in women, and it is the third most common cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [1, 2]. Liver resection, local ablation therapy, and liver transplantation are the suggested curative therapies for HCC, while transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) has been used to treat unresectable HCC with some clinical efficacy [3–5].

Anthracyclines, such as doxorubicin or epirubicin, have been widely used to treat advanced HCC, to prevent or treat postoperative recurrence, and to downstage the disease before liver transplantation by systemic infusion or by transarterial route [6, 7]. Acting as topoisomerase-II inhibitors, anthracycline drugs induce DNA damages and acute oxidative stress in cells [8, 9]. And the quinine group of anthracyclines can cause one electron reduction to produce a semiquinone [9, 10]. The free radical semiquinone consequently produces reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide anions, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals [9, 10]. ROS are reported to be involved in epirubicin-induced apoptosis in hepatoma cell lines [10]. Furthermore, epirubicin is less cardiotoxic than doxorubicin [6]. Therefore, epirubicin is widely used in Europe and Asia in the treatments of cancers, including HCC [6, 8].

However, the side effects of anthracyclines include cardiomyopathy, immunosuppression, and the development of primary or secondary drug resistance, which may sometimes adversely affect survival, recurrence, and extrahepatic metastases in HCC patients [11–13]. And HCC cells themselves are usually resistant to chemotherapeutic agents, the response rates of chemotherapy in HCC are reported to be only 10.5%–20.6%, and, generally, overall survivals have been less than 12 months for advanced HCC patients [6, 12].

Autophagy, a survival mechanism of some cancer cells, can be induced during starvation, chemotherapy, radiation, hypoxia, and some endocrine therapies [14, 15]. Sun et al reported that autophagy could protect breast cancer cells from epirubicin-induced apoptosis and facilitate the development of epirubicin resistance [16]. Progesterone can reverse multidrug resistance gene expression in epirubicin-treated urethral cancer cell lines via p-glycoprotein pathway [17]. And megestrol (a progestin drug) treatment has produced some efficacy in advanced HCC in some clinical studies [18, 19]. Therefore, combining epirubicin with progesterone might be a potential strategy for treating HCC, as it might allow for the smaller doses of epirubicin, which is generally toxic, while increasing its effectiveness against HCC and decreasing epirubicin-related side effects.

Our previous study showed HA22T/VGH cells are susceptible to changes in redox status and oxidative stresses also induce apoptosis in these cells [20]. This study tested the effect of combining epirubicin with progesterone to treat a metastatic, poorly differentiated HCC cell line, HA22T/VGH. To evaluate the therapeutic effect of this combination, we analyzed occurrence of apoptosis and autophagy, expressions of their related proteins, and the expression of multidrug resistance-related protein 1 (MRP-1) gene.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Antibodies

Epirubicin hydrochloride (Pharmorubicin) was purchased from Pfizer Italia S.R.L. (Milano, Italy), progesterone from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), acridine orange from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA), protein assay reagents from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA), and TRIzol reagent from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). All other chemicals were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Mouse monoclonal antibodies against light chain-3 (LC-3), Beclin-1, or Bax, rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Bcl-XL, and goat polyclonal antibodies against β-actin were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse, -goat, and -rabbit IgG antibodies were purchased from BD Pharmingen Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA).

2.2. Cell Line, Cell Culture, and Drug Treatments

HA22T/VGH cell line was obtained from the Food Industry Research and Development Institute in Hsinchu, Taiwan (BCRC number: 60168) and was cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone, Auckland, NZ), 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA), 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA), 100 units/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) at 37°C in a humidified chamber with 5% CO2. To investigate the effects of epirubicin and progesterone, various concentrations of epirubicin and progesterone were added to the culture medium for an indicated time period and then the cells were harvested and analyzed.

2.3. Cell Growth

After epirubicin and progesterone treatment, the cells were harvested and viable cells were counted using a dye exclusion technique as described previously [21]. Briefly, the cell suspension was centrifuged at 5,000 ×g; the supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was resuspended in serum-free medium. One volume of 0.4% Trypan blue (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) was added to one volume of cell suspension, and then cells were counted in a hemocytometer after incubation at room temperature for 3 min. All counts were done in triplicate.

2.4. TUNEL Assay

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assays were performed using an APO-BrdU TUNEL Assay Kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) according to the manufacturer's directions as described previously [21]. Briefly, the cells were incubated for the indicated time before being trypsinized, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) for 15 min. The fixed cells were washed twice in PBS and stored at −20°C in 70% ethanol for 12–18 h prior to performing the TUNEL assay. After removing the 70% ethanol by centrifugation, the cells were washed twice in wash buffer and then incubated at 37°C for 60 min with DNA-labeling solution containing terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase and BrdUTP. After washing twice with rinse buffer, the cells were resuspended for 30 min in the dark at room temperature in antibody solution containing Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-BrdU antibody. Flow cytometric analysis was subsequently performed using a Coulter Epics XL cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL, USA) to quantify the fluorescence intensity for determination of apoptotic status. The data were analyzed using WINMDI software version 2.8 (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA), with a minimum of 1 × 104 cells per sample being evaluated in each case.

2.5. Caspase-3 Colorimetric Protease Assay

The activity of caspase-3 was detected using an ApoTarget caspase-3 colorimetric protease assay kit (Invitrogen Corp., Camarillo, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions as described previously [21]. Briefly, we induced apoptosis in cells by epirubicin and/or progesterone treatments while concurrently incubating a control culture without induction. We then counted cells as pellet 3–5×106 cells per sample. The cells were resuspended in 50 μL of chilled Cell Lysis Buffer, incubated on ice for 10 min, and then centrifuged for 1 min in a microcentrifuge (10000 ×g). Supernatant (cytosol extract) was transferred to a fresh tube and put on ice and protein assay reagents (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) were used. Each cytosol extract was diluted to a concentration of 50–200 μg protein per 50 μL Cell Lysis Buffer (1–4 mg/mL). A 50 μL of 2 × reaction buffer (containing 10 mM DTT) was added to each sample followed by 5 μL of the 4 mM DEVD-pNA substrate (200 μM of final concentration). The samples were incubated in the dark at 37°C for 2 h. Samples were read in a microplate reader set at 405 nm. Fold increase in caspase-3 activity was determined compared to that in untreated controls.

2.6. Detection of Autophagy with Acridine Orange Staining

Formation of acidic vesicular organelles (AVOs), a morphological characteristic of autophagy, was quantified by acridine orange staining as described previously [22]. In brief, acridine orange (1 μg/mL) was added 30 min prior to collection, and after being washed with PBS, cells were analyzed using the Coulter Epics XL cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL, USA). Green (510–530 nm) and red (>650 nm) fluorescence emission from 1 × 104 cells illuminated with blue (488 nm) excitation light was measured. The data were analyzed using WINMDI software version 2.8 (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA), with a minimum of 1 × 104 cells per sample being evaluated in each case.

2.7. Western Blotting

Sample preparation and Western blotting procedures were performed as described previously [21]. Briefly, cells were harvested and cytosolic extracts were prepared using lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2), 2 mM EGTA, 5 mM EDTA, 500 μM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM sodium fluoride, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitor cocktail). Protein concentrations were determined using protein assay reagents. Forty to sixty micrograms of protein lysate was analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. After transfer of the proteins from the gel to a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany), the membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) containing 5% nonfat dry milk, and then they were incubated with specific primary antibodies and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. The immunoreactive bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA, USA).

2.8. Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions as described previously [23]. The complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from random hexadeoxynucleotide primed reverse transcription from 2 μg of total RNA using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega Corporation, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's directions. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was then performed using the Dream Taq DNA polymerase (Thermo scientific, MA, USA) on an Applied Biosystems Gene Amp9700 PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA, USA). The thermocycling began with 94°C for 5 min followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, and then followed by 70°C for 10 min. PCR primers sequences were as follows: multidrug resistance-related protein 1 (MRP-1) forward, 5′-AGG TGGACCTGT TTC GTG AC-3′; reverse, 5′-ACCCTGTGATCCACCAGAAG-3′, and GAPDH forward, 5′-GAC ATC AAG AAG GTG GTG AAG CAG-3′; reverse, 5′-GCG TCA AAG GTG GAG GAG TGG-3′. The amplified PCR products were analyzed on 2% agarose gels and photographs were taken. The intensity of each band was calculated by densitometry analysis and the results were expressed as a percentage of the optical density of the corresponding GAPDH band.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Comparisons among the groups of cells, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Fisher's least significant difference test were performed using the SPSS 17.0 statistical software (SPSS, Chicago, IL). All experiments were performed at least thrice. All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). Value differences were considered significant if P < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Inhibition of Cell Growth

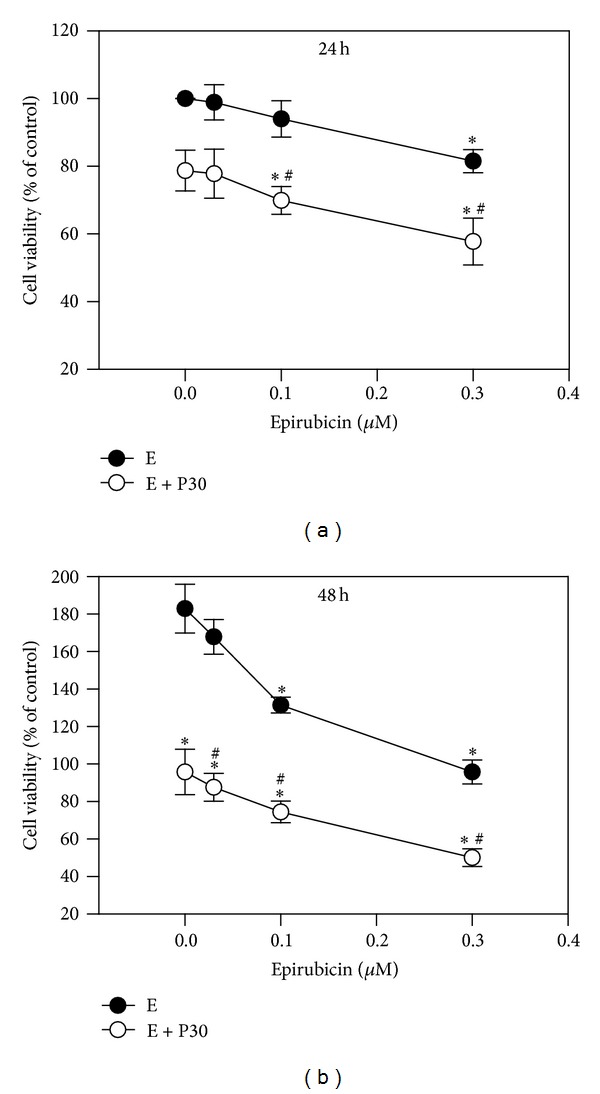

To gain initial insight into the effects of epirubicin alone or in combination with progesterone on cell growth of hepatoma cell line, HA22T/VGH cells were treated for 24 or 48 h without or with different doses of epirubicin in the absence or presence of 30 μM progesterone. The IC50 of progesterone was 100 μM and almost not cytotoxic to HA22T/VGH cells at concentrations <50 μM (data not shown). Therefore, a concentration of 30 μM progesterone was the dosage chosen for the cotreatment with epirubicin. During the 24 h incubation period, the untreated HA22T/VGH cells proliferated, while the growth of the cells treated with epirubicin ≥0.3 μM was significantly inhibited. The addition of 30 μM progesterone significantly augmented epirubicin's inhibition of growth at concentration of ≥0.1 μM (Figure 1(a)). During 48 h incubation, epirubicin inhibited cell growth in a dose-dependent manner and the coaddition of progesterone augmented its effect (Figure 1(b)).

Figure 1.

Effects of epirubicin on cell growth without or with progesterone addition. HA22T/VGH cells were treated with different concentrations of epirubicin without or with 30 μM progesterone for 24 h (a) or 48 h (b). Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) for three separate experiments. E: epirubicin; P30: 30 μM progesterone. *P < 0.05 compared to the corresponding untreated controls. # P < 0.05 compared to the corresponding epirubicin-treated group.

3.2. Induction of Apoptosis and Expressions of Apoptosis-Related Proteins

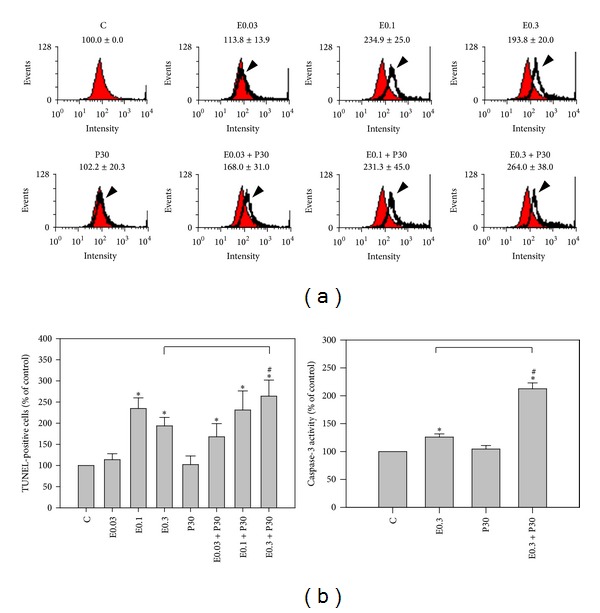

Apoptotic cells were measured by flow cytometric analysis after TUNEL staining (Figure 2(a)). After 24 h treatment with epirubicin, a significant increase in the percentage of TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells was seen as compared with controls at concentrations ≥0.1 μM epirubicin. Although progesterone alone did not cause a significant change in the number of apoptotic cells, using it in combination with epirubicin at concentrations ≥0.3 μM had a stronger effect. The fluorescence intensities of apoptotic cells of HA22T/VGH cells treated with 30 μM progesterone, 0.3 μM epirubicin, or combination therapy were 102.2 ± 20.3%, 193.8 ± 20.0%, and 264.0 ± 38.0%, respectively, compared with those of controls (Figure 2(a)). Figure 2(b) shows that adding 30 μM progesterone to 0.3 μM epirubicin treatment produced more caspase-3 activity (212.5 ± 10.6%) than using 0.3 μM epirubicin alone (126.0 ± 5.7%). These results showed epirubicin at concentration of 0.3 μM activated caspase-3 and induced apoptosis, and combining the two drugs had a significant effect on apoptosis in HA22T/VGH cells.

Figure 2.

Apoptosis induction by epirubicin without or with progesterone addition. HA22T/VGH cells were treated with indicated concentrations of epirubicin without or with 30 μM progesterone for 24 h and evaluated by (a) TUNEL staining or (b) caspase-3 activity. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) for three separate experiments. C: untreated cells, E0.03: 0.03 μM epirubicin, E0.1: 0.1 μM epirubicin, E0.3: 0.3 μM epirubicin, and P30: 30 μM progesterone. *P < 0.05 compared to the untreated controls. # P < 0.05 compared to the corresponding epirubicin-treated group.

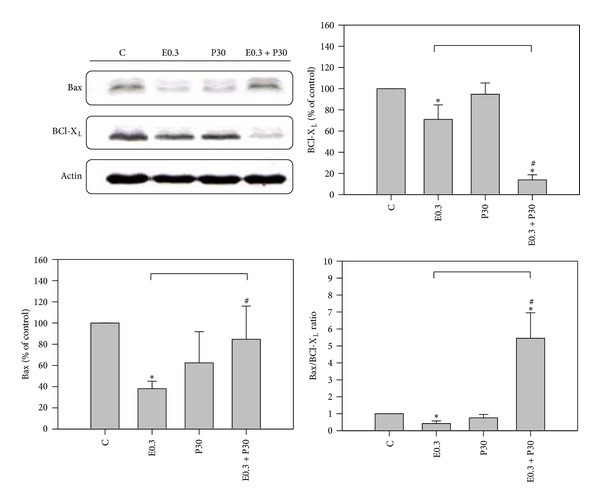

To determine whether the treatment-induced apoptosis was associated with altered expression of apoptosis-relating proteins, HA22T/VGH cells were treated for 24 h with 0.3 μM epirubicin in the presence or absence of 30 μM progesterone and analyzed by Western blotting. Figure 3 shows that progesterone alone had no significant effect (94.8 ± 10.6% versus 100 ± 0.0%) on the antiapoptotic protein, Bcl-XL levels, whereas epirubicin caused a decrease (71.1 ± 13.6% versus 100 ± 0.0%; P < 0.05), compared with those of controls. The combination of epirubicin and progesterone caused a marked decrease in expression of Bcl-XL compared to 0.3 μM epirubicin alone (13.9 ± 4.8% versus 71.1 ± 13.6; P < 0.05). Meanwhile, progesterone alone had no effect on the proapoptotic protein, Bax levels; epirubicin alone decreased Bax levels. The coaddition of progesterone and epirubicin significantly lessened the decrease of Bax levels compared to epirubicin alone (84.7 ± 31.3% versus 38.0 ± 7.1%; P < 0.05). Thus, the ratio of proapoptotic/antiapoptotic factor, Bax/Bcl-XL, was extremely enhanced by the combination therapy, which can partly explain why apoptosis was increased by the combination (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Western blotting shows Bax and Bcl-XL expressions of HA22T/VGH cells after epirubicin and/or progesterone treatment for 24 h. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) for three separate experiments. C: untreated cells, E0.3: 0.3 μM epirubicin, and P30: 30 μM progesterone. *P < 0.05 compared to the untreated controls. # P < 0.05 compared to epirubicin-treated group.

Activation of caspase-3 is an essential step in apoptosis. Our results demonstrated progesterone augmented caspase-3 activity of epirubicin-treated HA22T/VGH cells significantly. Epirubicin or doxorubicin can induce intracellular ROS [8, 9]. ROS production may interact with Fas-associated death domain (FADD) pathway and FADD sequence can result in activation of caspase-3 which has been reported in various cancer cell lines [24, 25]. This study also found that progesterone interfered with the expression of apoptosis-regulating proteins, upregulating Bax and downregulating Bcl-XL, in the epirubicin-treated HA22T/VGH cells. It is currently unknown whether progesterone initially triggers apoptosis upstream from caspase-3 or not. Bcl-XL expression is important for the inhibition of apoptosis initiated by various cellular stresses in human HCC cells [26, 27]. We, therefore, propose that the Bcl-2 family may contribute to the improved efficacy of treating HA22T/VGH cells with a combination of epirubicin and progesterone. On the other hand, the expression of the progesterone receptor and its potential role in HA22T/VGH cells have not been reported till now; however, some studies have evaluated the role of the progesterone receptor-mediated apoptosis in other human hepatoma cells. Cheng et al. demonstrated that treatment with RU486, a progesterone receptor antagonist, inhibits the progesterone-mediated response to estradiol pretreatment in tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptotic Huh-7 cells [28]. On the contrary, Zhang and Chow reported that the progesterone receptor is not involved in the action of megestrol-induced apoptosis in HepG2 cells [29]. Thus, further studies on the potential role of the progesterone receptor in HA2T/VGH cells are necessary.

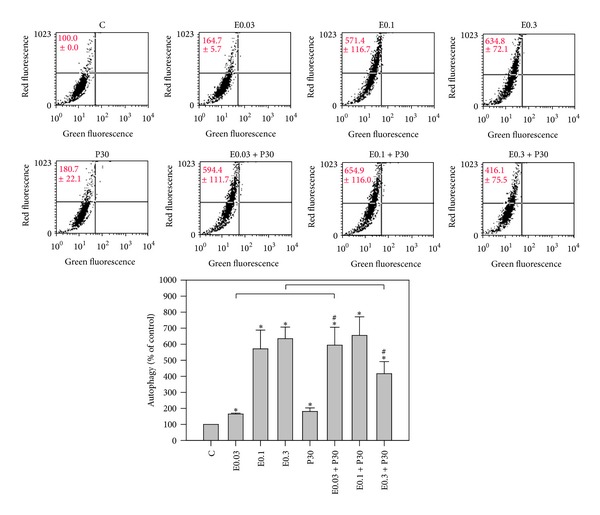

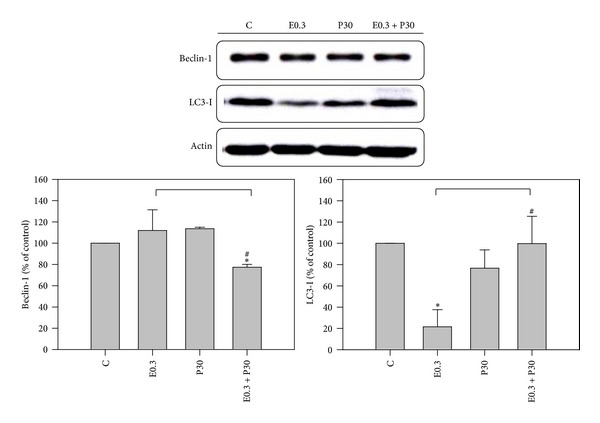

3.3. Autophagy Reduction by Combination

It has been reported that autophagy can be induced during chemotherapy [30, 31]. To determine whether the treatments had an effect on autophagy induction, HA22T/VGH cells were treated for 24 h with 0.3 μM epirubicin in the presence or absence of 30 μM progesterone, then subjected to acridine orange staining, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Figure 4 shows both epirubicin and progesterone increased autophagy compared to controls by AVOs analysis, though epirubicin was more effective than progesterone. Surprisingly, coaddition of progesterone significantly reduced the epirubicin-induced increase of autophagy. To further explore the expression of autophagy-related proteins, HA22T/VGH cells were treated for 24 h with 0.3 μM epirubicin in the presence or absence of 30 μM progesterone and then subjected to Western blotting. As shown in Figure 5, neither epirubicin nor progesterone had an effect on Beclin-1 levels, but the combination of the two significantly reduced Beclin-1 levels. The expressions of proteins of Beclin-1 of HA22T/VGH cells treated with 0.3 μM epirubicin, 30 μM progesterone, or combination therapy for 24 h were 119.9 ± 19.5%, 113.6 ± 1.4%, and 77.4 ± 2.6%, respectively, compared with those of controls. Figure 5 also shows progesterone had no effect on LC3-I levels, whereas epirubicin markedly reduced LC3-I levels, indicating that it may convert LC3-I to LC3-II. Interestingly, coaddition of progesterone to epirubicin treatment significantly reversed LC3-I levels. The expressions of proteins of LC3-I of HA22T/VGH cells treated with 0.3 μM epirubicin, 30 μM progesterone, or combination therapy for 24h were 21.5 ± 16.2%, 76.6 ± 17.3%, and 99.8 ± 25.6%, respectively, compared with those of controls. This is compatible with the results of AVOs formation shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Epirubicin and/or progesterone effect on autophagy induction. HA22T/VGH cells were treated with epirubicin and/or progesterone for 24 h then stained with acridine orange and followed by flow cytometric analysis of autophagy. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) for three separate experiments. C: untreated cells, E0.03: 0.03 μM epirubicin, E0.1: 0.1 μM epirubicin, E0.3: 0.3 μM epirubicin, and P30: 30 μM progesterone. *P < 0.05 compared to the untreated controls. # P < 0.05 compared to epirubicin-treated group.

Figure 5.

Western blotting shows Beclin-1 and LC3-I expressions in HA22T/VGH cells after epirubicin and/or progesterone treatment for 24 h. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) for three separate experiments. C: untreated cells, E0.3: 0.3 μM epirubicin, and P30: 30 μM progesterone. *P < 0.05 compared to the untreated controls. # P < 0.05 compared to epirubicin-treated group.

Many studies have indicated that autophagy can serve as a survival mechanism for cancer cells and suggested that autophagy inhibitor might enhance the antitumor effects of chemotherapy or target therapy agents in vivo [30, 31]. In addition, Shen et al. reported inhibition of autophagy could enhance proapoptotic effects of ZD6474 in glioblastoma cells [31]. Greene et al. also reported inhibition of late-stage autophagy synergistically enhanced pyrrolo-1, 5-benzoxazepine-6-induced apoptotic cell death in human colon cancer cells [32]. In this study, progesterone was found to be able to reduce epirubicin-induced autophagy in HA22T/VGH cells. There are some interactions between autophagy and apoptosis mediated by Beclin-1 and Bcl-XL proteins [32–34]. Beclin-1 is an autophagy-related protein, while Bcl-XL is an anti-apoptosis-related protein. However, Bcl-XL and Bcl-2 have been reported to be negative regulators of Beclin-1 [33–35]. Bcl-XL can inhibit Beclin-1 activity by stabilizing Beclin-1 homodimerization [34]. Akar et al. reported that doxorubicin induced autophagy through the upregulation of Beclin-1, which was further enhanced by siRNA-mediated Bcl-2 silencing MCF-7 cells [36]. The expressions of Beclin-1 and AVOs were compatible in Figures 4 and 5, indicating that 30 μM progesterone could decrease the expression of AVOs in HA22T/VGH cells treated with 0.3 μM epirubicin and these effects may be induced by suppression of expression of Beclin-1. In contrast, the present study found that after progesterone was added, the expressions of Bcl-XL and Beclin-1 both were reduced. Our results proved that progesterone in combination with epirubicin could increase the epirubicin-induced apoptosis and decrease epirubicin-induced autophagy in HA22T/VGH cells. Therefore, the decreased expression of Beclin-1 could not be explained by the interactions between Beclin-1 and Bcl-XL described above.

Thus, Figure 4 displays progesterone increased autophagy compared to controls maybe due to the fact that 30 μM progesterone does not augment the expression of Bcl-XL shown in Figure 3. It has been demonstrated that the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)—myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) pathway can mediate lipopolysaccharide (LPS)—induced autophagy by reducing the binding of Beclin-1 and Bcl-2 and thus triggers autophagy activation in human and murine macrophages [37, 38]. Su et al. reported progesterone inhibited TLR4-mediated innate immune response in murine macrophages [39]. Hepatocytes also express TLR4 receptors and are responsive to LPS [38, 40]. Our preliminary study also shows combination of progesterone and epirubicin can decrease epirubicin-induced expression of TLR4 and MyD88 and sequent production of interlukin-6 in HA22T/VGH cells (unpublished data). Thus, coaddition of progesterone significantly reduced the epirubicin-induced autophagy in HA22T/VGH cells which may be caused by inhibition of TLR4-MyD88 pathway by progesterone. However, further studies on the potential role of TLR4 and MyD88 pathway in HA22T/VGH cells are necessary.

The microtubule-associated protein 1-light chain-3 (LC3) is an ubiquitin-like molecule which is a mammalian homologue of the autophagy-related Atg8 encoded product in yeast [41]. During the fusion of autophagosomal membranes, cytosolic LC3 (LC3-I) is conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) through two consecutive ubiquitylation-like reactions catalyzed by the E1-like enzyme (Atg7) and E2-like enzyme (Atg3) to form the LC3-phospholipid conjugate (LC3-II) [42, 43]. During the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes, intra-autophagosomal LC3-II is also degraded by lysosomal proteases [41, 43]. In this study, we found epirubicin alone enhanced the formation of AVOs but decreased the expression of LC3-I, whereas coaddition of progesterone decreased the formation of AVOs and reversed the expression of LC3-I. These results indicate that epirubicin may promote the turnover of LC3-I to LC3-II, a possibility that is compatible with epirubicin-induced formation of AVOs during the same incubation period (24 h). And addition of progesterone to epirubicin to treat HA22T/VGH cells significantly decreased epirubicin-induced autophagy.

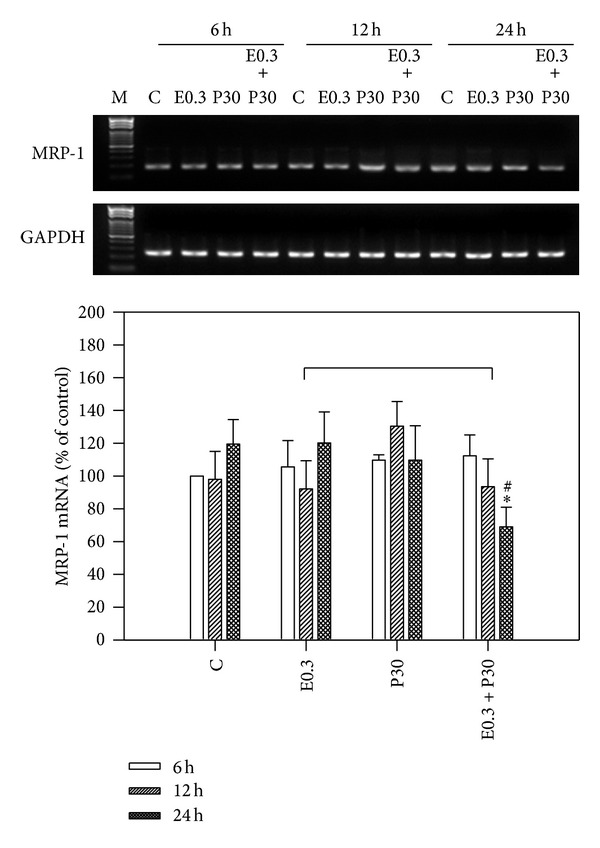

3.4. Decrease of Multidrug Resistance-Related Protein 1 (MRP-1) mRNA Expression by Combination

We examined the MRP-1 mRNA expression in 0.3 μM epirubicin and/or 30 μM progesterone treated HA22T/VGH cells for 6, 12, or 24 h by RT-PCR analysis. As Figure 6 shows, there was no significant difference in MRP-1 mRNA expression by epirubicin and/or progesterone treatment for 6 h or 12 h, whereas cotreatment of epirubicin and progesterone produced lower MRP-1 mRNA expression after 24 h treatment, suggesting that the combination might lessen drug resistance in HA22T/VGH cells. The expressions of MRP-1 mRNA HA22T/VGH cells treated with 0.3 μM epirubicin, 30 μM progesterone, or combination therapy for 24 h were 120.1 ± 19.0%, 109.6 ± 21.0%, and 69.0 ± 12.0%, respectively, compared with those of controls. There are many studies indicating that chemotherapy can evoke drug resistance and that this resistance may be related to the expression of multidrug resistance-related protein gene, MRP-1 [44, 45]. Expression of multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP-1) has been commonly observed in liver tissue and HCC cell lines treated with doxorubicin [46, 47]. It also has been reported that enhanced autophagy can induce drug-resistance in epirubicin-treated breast cancer cells [16] and increase of autophagy can induce production of MRP-1 [48]. This study found that the addition of progesterone to epirubicin-treated HA22T/VGH cells significantly decreased the expression of multidrug resistance-related protein 1 (MRP-1) gene, a decrease that might be related to the reduction of autophagy. Because the mechanisms underlying this possibility are not fully clarified in this study, more in vitro and in vivo studies are required.

Figure 6.

Epirubicin and/or progesterone effect on MRP-1 expression. HA22T/VGH cells were treated with epirubicin and/or progesterone for 6, 12, or 24 h, and then MRP-1 mRNA was analyzed by RT-PCR. The MRP-1 mRNA expression was normalized to GAPDH mRNA. The density of band was expressed as the relative density compared to that in untreated cells (control), taken as 100%. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) for three separate experiments. C: untreated cells, E0.3: 0.3 μM epirubicin, and P30: 30 μM progesterone. *P < 0.05 compared to the untreated controls. # P < 0.05 compared to epirubicin-treated group.

4. Conclusions

Epirubicin is an anthracycline drug that can induce intracellular ROS [8, 9]. This study showed that epirubicin treatment inhibited the growth of HA22T/VGH cells in a dose-dependent manner. The addition of 30 μM progesterone, which was inactive by itself, augmented epirubicin's inhibition of growth of cancer cells. Cotreatment with progesterone resulted in enhancement of the epirubicin-induced apoptosis, as evidenced by greater increase in caspase-3 activity and in the ratio of the apoptosis-regulating protein, Bax/Bcl-XL. The cotreatment also caused a decrease in autophagy, but decreased Beclin-1 and reversed LC3-I expressions. Furthermore, this combination reduced mRNA expression of the multidrug resistance-related protein 1 (MRP-1) gene.

However, clinical results of systemic single-epirubicin chemotherapy for palliative treatment of advanced HCC or prevention of postoperative recurrence in HCC have not been suggested [3, 6, 11, 12]. However, local embolization of unresectable or advanced HCC with epirubicin or doxorubicin through hepatic artery (TACE) has been suggested as a palliative treatment in west and east countries [3, 4]. Therefore, the present study shows the coadministration of epirubicin and progesterone might be a feasible and rational choice of therapy for clinical HCC treatment and this combination is worth further evaluation. However, more in vitro and in vivo studies are required.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Council of Taiwan Grants NSC98-2314-B-037-028-MY1 and NSC98-2314-B-037-028-MY2, the Kaohsiung Medical University Grant KMU-Q101025, and the Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital Grant KMUH-96-6R33.

Abbreviations

- HCC:

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- AVOs:

Acidic vesicular organelles

- FADD:

Fas-associated death domain

- MRP-1:

Multidrug resistance-related protein 1

- ROS:

Reactive oxygen species

- LC-3:

Light chain-3

- TLR-4:

Toll-like receptor 4

- MyD88:

Myeloid differentiation factor 88.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contribution

Wen-Tsan Chang contributed to conception and design, analysis and interpretation, data collection, and writing of the paper. Hsiao-Ling Cheng and Bau-Shan Hsieh contributed to analysis and interpretation and data collection. Chien-Chih Chiu contributed to analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of the paper. King-Teh Lee and Kee-Lung Chang contributed to conception and design, analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the paper, and obtaining funding.

References

- 1.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(12):1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. International Journal of Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruix J, Sherman M. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53(3):1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Omata M, Lesmana LA, Tateishi R, et al. Asian pacific association for the study of the liver consensus recommendations on hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology International. 2010;4(2):439–474. doi: 10.1007/s12072-010-9165-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang WT, Kao WY, Chau GY, et al. Hepatic resection can provide long-term survival of patients with non-early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: extending the indication for resection? Surgery. 2012;152(5):809–820. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SJ, Seo HY, Choi JG, et al. Phase II study with a combination of epirubicin, cisplatin, UFT, and leucovorin in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2006;57(4):436–442. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green TJ, Rochon PJ, Chang S, et al. Downstaging disease in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma outside of milan criteria: strategies using drug-eluting bead chemoembolization. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 2013;24(11):1613–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kebieche M, Lakroun Z, Lahouel M, Bouayed J, Meraihi Z, Soulimani R. Evaluation of epirubicin-induced acute oxidative stress toxicity in rat liver cells and mitochondria, and the prevention of toxicity through quercetin administration. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology. 2009;61(2):161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salvatorelli E, Guarnieri S, Menna P, et al. Defective one- or two-electron reduction of the anticancer anthracycline epirubicin in human heart: relative importance of vesicular sequestration and impaired efficiency of electron addition. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(16):10990–11001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508343200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozkan A, Fişkin K. Epirubicin HCl toxicity in human liver-derived hepatoma G2 cells. Polish Journal of Pharmacology. 2004;56(4):435–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu AX, Fuchs CS, Clark JW, et al. A phase II study of epirubicin and thalidomide in unresectable or metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncologist. 2005;10(6):392–398. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-6-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeo W, Mok TS, Zee B, et al. A randomized phase III study of doxorubicin versus cisplatin/interferon α-2b/doxorubicin/fluorouracil (PIAF) combination chemotherapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97(20):1532–1538. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duvoux C, Kiuchi T, Pestalozzi B, Busuttil R, Miksad R. What is the role of adjuvant therapy after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma? Liver Transplantation. 2011;17(supplement 2):S147–S158. doi: 10.1002/lt.22367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahn JH, Lee M. Autophagy-dependent survival of mutant B-Raf melanoma cells selected for resistance to apoptosis induced by inhibitors against oncogenic B-Raf. Biomolecules & Therapeutics. 2013;21(2):114–120. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2013.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Mammalian autophagy: core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2010;22(2):124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun WL, Chen J, Wang YP, Zheng H. Autophagy protects breast cancer cells from epirubicin-induced apoptosis and facilitates epirubicin-resistance development. Autophagy. 2011;7(9):1035–1044. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.9.16521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewin J, Cooper A, Birch B. Progesterone: a novel adjunct to intravesical chemotherapy. BJU International. 2002;90(7):736–741. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.03013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villa E, Ferretti I, Grottola A, et al. Hormonal therapy with megestrol in inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma characterized by variant oestrogen receptors. British Journal of Cancer. 2001;84(7):881–885. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giacomin A, Sergio A, Vanin V, et al. Megestrol and embryonic extracts in the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective randomized trial in the pre-sorafenib era. Hepatology Research. 2010;40(2):153–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2009.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh BS, Huang LW, Su SJ, et al. Combined arginine and ascorbic acid treatment induces apoptosis in the hepatoma cell line HA22T/VGH and changes in redox status involving the pentose phosphate pathway and reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2011;22(3):234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng HL, Su SJ, Huang LW, et al. Arecoline induces HA22T/VGH hepatoma cells to undergo anoikis—involvement of STAT3 and RhoA activation. Molecular Cancer. 2010;9, article 126 doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paglin S, Hollister T, Delohery T, et al. A novel response of cancer cells to radiation involves autophagy and formation of acidic vesicles. Cancer Research. 2001;61(2):439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu YC, Cheng HL, Hsieh BS, Huang LW, Huang TC, Chang KL. Arsenic trioxide affects bone remodeling by effects on osteoblast differentiation and function. Bone. 2012;50(6):1406–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang HL, Fang LW, Lu SP, Chou CK, Luh TY, Lai MZ. DNA-damaging reagents induce apoptosis through reactive oxygen species-dependent Fas aggregation. Oncogene. 2003;22(50):8168–8177. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu WH, Chang LS. Arachidonic acid induces Fas and FasL upregulation in human leukemia U937 cells via Ca2+/ROS-mediated suppression of ERK/c-Fos pathway and activation of p38 MAPK/ATF-2 pathway. Toxicology Letters. 2009;191(2-3):140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ng KT, Guo DY, Cheng Q, et al. A garlic derivative, S-allylcysteine (SAC), suppresses proliferation and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031655.e31655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao J, Dong L, Lu B, et al. Down-regulation of osteopontin suppresses growth and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via induction of apoptosis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(3):956–968. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng X, Shimizu I, Yuan Y, et al. Effects of estradiol and progesterone on tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis in human hepatoma HuH-7 cells. Life Sciences. 2006;79(21):1988–1994. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang K, Chow PKH. The effect of megestrol acetate on growth of HepG2 cells in vitro and in vivo. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(15):5226–5232. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donohue E, Thomas A, Maurer N, et al. The autophagy inhibitor verteporfin moderately enhances the antitumor activity of gemcitabine in a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma model. Journal of Cancer. 2013;4(7):585–596. doi: 10.7150/jca.7030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen J, Zheng H, Ruan J, et al. Autophagy inhibition induces enhanced proapoptotic effects of ZD6474 in glioblastoma. British Journal of Cancer. 2013;109(1):164–171. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greene LM, Nolan DP, Regan-Komito D, Campiani G, Williams DC, Zisterer DM. Inhibition of late-stage autophagy synergistically enhances pyrrolo-1,5-benzoxazepine-6-induced apoptotic cell death in human colon cancer cells. International Journal of Oncology. 2013;43(3):927–935. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT, Tang D. The Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2011;18(4):571–580. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lama D, Sankararamakrishnan R. Molecular dynamics simulations of pro-apoptotic BH3 peptide helices in aqueous medium: relationship between helix stability and their binding affinities to the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-XL . Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design. 2011;25(5):413–426. doi: 10.1007/s10822-011-9428-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu LL, Cheng Y, Liu B. Beclin-1: autophagic regulator and therapeutic target in cancer. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2013;45(5):921–924. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akar U, Chaves-Reyez A, Barria M, et al. Silencing of Bcl-2 expression by small interfering RNA induces autophagic cell death in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Autophagy. 2008;4(5):669–679. doi: 10.4161/auto.6083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi CS, Kehrl JH. MyD88 and Trif target Beclin 1 to trigger autophagy in macrophages. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(48):33175–33182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804478200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mencin A, Kluwe J, Schwabe RF. Toll-like receptors as targets in chronic liver diseases. Gut. 2009;58(5):704–720. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.156307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Su L, Sun Y, Ma F, Lü P, Huang H, Zhou J. Progesterone inhibits Toll-like receptor 4-mediated innate immune response in macrophages by suppressing NF-κB activation and enhancing SOCS1 expression. Immunology Letters. 2009;125(2):151–155. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott MJ, Billiar TR. β2-integrin-induced p38 MAPK activation is a key mediator in the CD14/TLR4/MD2-dependent uptake of lipopolysaccharide by hepatocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(43):29433–29446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803905200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barth S, Glick D, Macleod KF. Autophagy: assays and artifacts. Journal of Pathology. 2010;221(2):117–124. doi: 10.1002/path.2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanida I, Yamasaki M, Komatsu M, Ueno T. The FAP motif within human ATG7, an autophagy-related E1-like enzyme, is essential for the E2-substrate reaction of LC3 lipidation. Autophagy. 2012;8(1):88–97. doi: 10.4161/auto.8.1.18339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaiser SE, Mao K, Taherbhoy AM, et al. Noncanonical E2 recruitment by the autophagy E1 revealed by Atg7-Atg3 and Atg7-Atg10 structures. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2012;19(12):1242–1249. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lo YL, Liu Y, Tsai JC. Overcoming multidrug resistance using liposomal epirubicin and antisense oligonucleotides targeting pump and nonpump resistances in vitro and in vivo. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2013;67(4):261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Villar VH, Vogler O, Martinez-Serra J, et al. Nilotinib counteracts P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance and synergizes the antitumoral effect of doxorubicin in soft tissue sarcomas. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037735.e37735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu F, Shao ZY, Zhai BJ, Zhao CL, Shen DM. Ultrasound reverses multidrug resistance in human cancer cells by altering gene expression of ABC transporter proteins and bax protein. Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. 2011;37(1):151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leslie EM, Deeley RG, Cole SPC. Multidrug resistance proteins: role of P-glycoprotein, MRP1, MRP2, and BCRP (ABCG2) in tissue defense. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2005;204(3):216–237. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lim SC, Hahm KS, Lee SH, Oh SH. Autophagy involvement in cadmium resistance through induction of multidrug resistance-associated protein and counterbalance of endoplasmic reticulum stress WI38 lung epithelial fibroblast cells. Toxicology. 2010;276(1):18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]