Abstract

Background

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are impaired in social communication and interaction with peers, which may reflect diminished social motivation. Many children with ASD show enhanced stress when playing with other children. This study investigated social and stress profiles of children with ASD during play.

Methods

We utilized a peer interaction paradigm in a natural playground setting with 66 un-medicated, pre-pubertal, children 8 to 12 years (38 with ASD, 28 with typical development (TD)). Salivary cortisol was collected before and after a 20-minute playground interaction that was divided into periods of free and solicited play facilitated by a confederate child. Statistical analyses included Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, mixed effects models and Spearman correlations to assess the between-group differences in social and stress functioning, identify stress responders, and explore associations between variables, respectively.

Results

There were no differences between the groups during unsolicited free play; however, during solicited play by the confederate, significant differences emerged such that children with ASD engaged in fewer verbal interactions and more self-play than the TD group. Regarding physiological arousal, children with ASD as a group showed relatively higher cortisol in response to social play; however, there was a broad range of responses. Moreover, those with the highest cortisol levels engaged in less social communication.

Conclusions

The social interaction of children with ASD can be facilitated by peer solicitation; however, it may be accompanied by increased stress. The children with ASD that have the highest level of cortisol show less social motivation; yet, it is unclear if it reflects an underlying state of heightened arousal or enhanced reactivity to social engagement, or both.

Keywords: Autism, cortisol, play, stress, social, interaction, behavior

INTRODUCTION

It has been proposed that deficits in social motivation are fundamental to nearly all children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD; (Chevallier, Kohls, Troiani, Brodkin, & Schultz, 2012)) and that poor social cognition (Baron-Cohen, 1995) is considered consequential (not causal). While this notion is appealing in that it provides a framework for the deficits in social orienting, seeking, and maintaining behavior, it does not consider the substantial portion of children with ASD that demonstrate clear social interest and motivation. The characterization of autism as a spectrum disorder has a long history (Kanner, 1943; Wing & Gould, 1979). Moreover, children with ASD are heterogeneous across biological parameters including social (oxytocin) and stress (cortisol) hormones that may impact social functioning (Corbett, Schupp, Simon, Ryan, & Mendoza, 2010; Modahl et al., 1998). Finally, despite changes in diagnostic classification (APA, 2013), the domains of functioning remain diverse; therefore, the examination of phenotypic biobehavioral profiles, including motivational tendencies with peers, may reveal differences in the developmental trajectory of children with ASD and serve as a valuable guide to more individualized treatment of social functioning.

The rudiments of social skills are acquired through observational learning (Bandura, 1986) and a fundamental component is the motivation to engage in the observed behavior. Play is a primary training ground for children (Piaget & Inhelder, 1969; Vygotsky, 1978), facilitating the development of a variety of cognitive, motor, and social skills (Pellegrini & Smith, 1998). However, if a child fails to engage in these rudimentary activities with peers (Boucher & Wolfberg, 2003) a variety of age-appropriate perceptual, expressive, imaginative and problem-solving skills may not adequately develop. Subsequently, children with ASD seldom engage in spontaneous, age-appropriate play (Honey, Leekam, Turner, & McConachie, 2007; Yuill, Strieth, Roake, Aspden, & Todd, 2007) and many show a preference for self-play rather than interacting with peers (Humphrey & Symes, 2011).

When children with ASD do interact with peers, many experience increased anxiety (Bellini, 2006) and stress (Corbett, et al., 2010; Lopata, Volker, Putnam, Thomeer, & Nida, 2008). Additionally, children with ASD often do not form interpersonal relationships with peers (Krasny, Williams, Provencal, & Ozonoff, 2003) and are frequently subjected to ridicule and rejection (Church, Alisanski, & Amanullah, 2000). These negative experiences and increased insight into their limitations in social competence (Knott, Dunlop, & Mackay, 2006) may exacerbate social anxiety and stress especially with peers (Bellini, 2006; Schupp, Simon, & Corbett, 2013; White, Oswald, Ollendick, & Scahill, 2009).

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis regulates many bodily processes and interactions, including reactions to psychological stress (Herman & Cullinan, 1997). The primary stress hormone in humans, cortisol, is secreted from the adrenal cortices in response to stress (Hennessey & Levine, 1979; Herman & Cullinan, 1997). Regarding psychosocial stress, context, insight, and a perceived sense of threat mediates stress responsivity (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004; J. W. Mason, 1968). Many children with ASD show higher cortisol when socially interacting with unfamiliar peers during play conditions (Corbett, et al., 2010; Lopata, et al., 2008); yet, they do not activate the HPA axis during a social performance-based task that reliably increases cortisol in typically developing children e.g., (Corbett, Schupp, & Lanni, 2012; Lanni, Schupp, Simon, & Corbett, 2012). Importantly, considerable variability in stress responsivity is evident in this heterogeneous disorder (Lopata, et al., 2008; Schupp, et al., 2013). Thus, an enriched understanding of the biobehavioral profiles of social stress in ASD is warranted.

One way to explore the social world of children with ASD is to study them in natural social situations; namely, during play. Indeed, the study of play during natural contexts using careful, unobtrusive observation can provide important insight into developmental, psychological, and physiological factors that impact social engagement in ASD. The Peer Interaction Paradigm, which permits the study of peer play in a naturalistic setting, has proven to be a useful, valid and informative approach (Corbett, et al., 2010). Early results suggest that children with ASD tend to engage in less social interaction with peers, which may be accompanied by increased arousal that can be moderated by age and developmental effects (Corbett, et al., 2012; Corbett, et al., 2010; Schupp, et al., 2013). The social, behavioral and biological profiles of children with ASD are on a continuum of responsivity. Therefore, the identification of underlying social stress profiles may be informative and guide treatment approaches based on the motivational and arousal patterns exhibited when specifically solicited by others. This investigation is intended to help identify the biological (cortisol) and behavioral (social) patterns that characterize children into social stress responders and nonresponders.

Social motivation includes aspects of seeking and maintaining behavior with others (Chevallier, et al., 2012), which can be examined during reciprocal exchange and measured by the duration of verbal and play behaviors with peers. In the current study, social motivation was characterized by the extent to which the participants were engaged in verbal interaction and cooperative play during solicited periods of play. It was hypothesized that children with ASD would show less social motivation relative to TD children.

We also aimed to characterize the response profiles of salivary cortisol by examining the baseline, magnitude (physiological arousal) and individual differences (responder status) in salivary cortisol and the degree to which stress values were associated with domains of social functioning. It was hypothesized that children with ASD would show elevated cortisol during play compared to TD peers, and exhibit associations between cortisol levels and social behavior during periods of solicited play revealing distinct biobehavioral profiles within the ASD group.

METHODS

Participants

The sample consisted of 66 un-medicated, pre-pubertal, healthy, children between 8-and-12 years old, 38 with ASD (mean = 10.03 years) and 28 with TD (mean = 9.62 years). The gender composition included 8 females, 4 in each group. The ASD group consisted of 21 with autistic disorder, 5 with PDD-NOS, and 12 with Asperger syndrome. ASD diagnosis was based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV) criteria (APA, 2000) and established by all of the following: (1) a previous diagnosis by a psychologist, psychiatrist, or behavioral pediatrician with ASD expertise; (2) current clinical judgment (BAC or CN) and (3) corroborated by the ADOS (Lord et al., 2000), administered by research-reliable personnel.

The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board approved the study. Informed written consent was obtained from parents and verbal assent was obtained from research participants prior to inclusion in the study. Participants were recruited by IRB approved flyers and recruitment systems via clinics, subject tracking systems, resource centers, support groups, schools, and recreational facilities.

As described below, the study included children that served as confederates (actor that participates in a study) whose parents provided informed consent to train for and participate in the study. Confederates were selected based on three primary characteristics: pleasant social interaction skills, genuine interest in playing with children with and without disabilities, as well as an ability to follow verbal instructions and turn them into age appropriate play behaviors. The majority of the confederates had previously participated in research or served as a peer helper for children with disabilities. Confederates were trained through the use of an instruction manual, direct skills modeling, and playground practice prior to serving as a confederate. The confederates were of the same age and gender as the ASD and TD participants. Moreover, the confederates were unfamiliar with both the ASD and TD children. During the course of the study, six confederates were utilized, 4 boys and 2 girls. The confederates engaged both the ASD and TD child for each solicited play period.

Diagnostic Variables

Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) (Lord, et al., 2000) is a semi-structured interview designed to assess behaviors characteristic of ASD. Test-retest reliability for the domains include: social .78, communication .73, social-communication .82, and restricted, repetitive behavior .59. Internal consistency using Chronbach’s alpha for Social-Communication was high across all modules (91 – .94).; (Lord, et al., 2000)

Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) (Wechsler, 1999) is a measure of cognitive ability used to obtain an estimate of intellectual functioning. Inclusion in the study required an estimated IQ of 80 or higher. Test-retest reliability has been reported ranging from .76 – .85 for each subtest and .95 for the full-scale estimated IQ (Wechsler, 1999). Convergent validity is reportedly good compared to other abbreviated measures of cognitive functioning (correlations ranging from .79 to .86) (Canivez, Konold, Collins, & Wilson, 2009).

Pubertal Development Scale (PDS) is a parent report measure providing an estimate of the participant’s level of pubertal development (Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988). The scale estimates stage of puberty by assigning a score ranging from “1” (change not yet begun) to “4” (complete) in each of 5 categories (e.g., voice, pubic hair, and facial hair). The reliability of the PDS is respectable with alpha coefficients representing internal consistency ranging from .68–.83. Regarding validity, correlations between PDS and physician ratings range between .61 and .67 (Brooks-Gunn, Warren, Rosso, & Garguilo, 1987).

Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) (Rutter, Bailey, & Lord, 2003) was used as a screening tool for ASD (scores of ≥15 is suggestive of ASD while scores of ≥22 are suggestive of autism). The exclusion criteria for TD children was a score ≥10. The SCQ shows good discrimination between ASD and non-ASD (sensitivity 0.88 and specificity 0.72) (Chandler et al., 2007).

Peer Interaction Playground Paradigm

The Peer Interaction Paradigm was developed to examine social exchanges within a playground environment occurring between children with and without autism (Corbett, et al., 2010). The 20-minute paradigm incorporated periods of free play and opportunities of cooperative play that is facilitated by a typically developing confederate child of the same age and gender. Unique to previous reports (Corbett, et al., 2010; Schupp, et al., 2013), the current study was conducted on a much larger playground (130 by 120 ft. vs. 60 by 60 ft. fenced in play area) that is part of the Vanderbilt University preschool. For the duration of the protocol, research personnel remained in the building allowing the participants to engage in more natural play behavior.

Interactions were video recorded using state-of-the-art equipment, which included four professional Sony EVI D70 (Sony, New York, NY, USA) remotely operated cameras housed in glass cases and affixed to the four corners of the external fence of the playground. The cameras contain pan, tilt and zoom features allowing full capture of the playground. Remote audio communication was established by Motorola MC22OR GMRS-FRS (Motorola, Libertyville, IL, USA) and Audio-Technica (Audio-Technica, Stow, Ohio, USA) transmitters and receivers, which functioned as battery-operated microphones that were clipped to the shirt of each child and simultaneously recorded by an 8 channel mixing board.

The interaction paradigm involved a child with ASD, a TD child, and a confederate of the same age and gender. Each subject only participated in one 20-minute session for the study resulting in three subjects in each observation group. The confederate, who was already on the playground when the two other children were brought out together, provided behavioral structure to the play by permitting key interactive sequences to occur within an otherwise natural interaction and setting. The confederate maintained an even level of play to prevent increased aerobic activity, which could affect cortisol levels. The trained confederate solicited play simultaneously from the two research participants following a cue provided by research personnel through an earpiece with a remote transmitter. All three children were unfamiliar to each other remained on the playground for the duration of play. Each subject only participated in one 20-minute session with three subjects in each observation group.

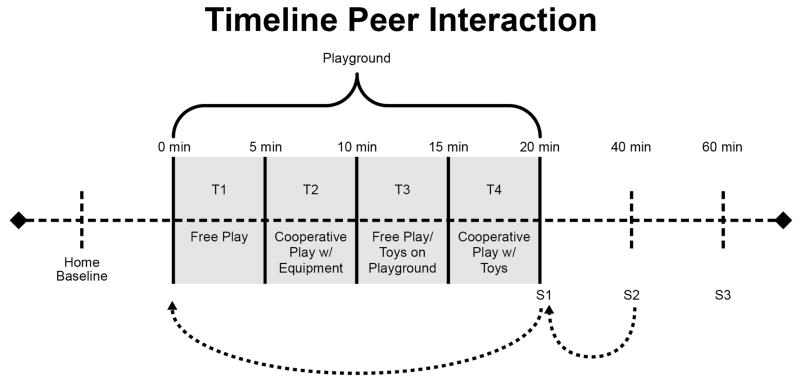

The paradigm was divided into four 5-minute time (T) periods of intermittent free play and solicited play (see Figure 1). The first period (T1) consisted of unsolicited free play. During the second period (T2), the confederate solicited interaction on the play equipment for cooperative play. During the third period (T3), the confederate was instructed to again engage in free play. During the fourth period (T4), the confederate again solicited the two participants to engage in a cooperative game involving toys.

Figure 1.

Peer Interaction Timeline

Immediately before and following the paradigm, the ASD and TD participants were each assigned to an individual room and sat with a research assistant. A similar bag of play and reading materials was provided to each child and included: a puzzle, a lego kit, and a coloring activity book. If the child brought toys to the visit, they were not allowed in the room to maintain consistency of play materials and experience across participants.

Behavior Coding

The Observer XT Version 8.0 software was used for the collection and analysis of the interaction observational data (Noldus, 2008). Data were analyzed based on a predefined list of operationalized behaviors (Corbett, et al., 2010; Schupp, et al., 2013) by raters that were research-reliable and not aware of the current study aims. Reliability was calculated for a random sample of 25% of observations using the Noldus Observer software. Inter-rater reliability was calculated using Cohen’s Kappa at K = 0.80 while test-retest reliability was K = 0.89. Verbal and play (cooperative, self) interactions were calculated as percentage of time engaged (verbal 90% and k = 0.85; play 91% and K = 0.89). Equipment use was used to code basic playground activities (87% and k = 0.74), whereas verbal initiation (100%, k = 1), and verbal rejection (90% and K = 0.85) were event variables.

Data were analyzed using both standard ethological approach by examining frequency, duration, and direction of the target behaviors and using a transactional approach (i.e., a who does what to whom format) based on a predefined list of operationalized behaviors (Lyons, Mason, & Mendoza, 1990; Lyons, Mendoza, & Mason, 1992; W. Mason, Long, & Mendoza, 1993; Mendoza & Mason, 1989). The transactional approach evaluates “interactions” of engagement that begin with an overture by one participant initiating a sequence of behaviors occurring between two or more children. These interactions involve the participant’s attempt to alter their immediate state of association with another child by a cooperative or competitive response. Within each interaction, the immediate responses of the participant’s and that of the other children were coded. Shifts in orientation and proximity are also coded and assist in determining the end of a bout. Coding was accomplished by observing and coding each participant’s behavior separately while simultaneously viewing all camera points-of-view, which allowed the coder to capture the optimal transaction moment.

The variables were operationalized as follows: Verbal Interaction was defined as an engagement between two or more children that begins with a verbal overture (Verbal Initiation) by one participant and continues in a reciprocal sequence of to-and-fro communication. Cooperative Play was defined as the percentage of time engaged in a reciprocal activity for enjoyment that involved and relied on the participation of two or more children (e.g., throwing a ball back-and-forth, hide and seek). Self-Play was defined as engaging in an activity for enjoyment independent of other children (e.g., ride a tricycle). Equipment Use (alone and with a group) was defined as using the play apparatus (e.g., slide, swing) or toys (e.g., bike). Verbal Initiation was defined as a verbal overture to another child soliciting their attention for communication or play. Verbal Rejection was defined as thwarting the request of another child through verbal or gestural refusal or spatial distancing (e.g., turning away from other child). As noted above, social motivation was characterized by the extent to which the participants were engaged in verbal interactions and cooperative versus self-play during solicited periods of time (T2 and T4). The interactions were calculated as total time spent engaged verbally (verbal interaction) or during play (cooperative or self) with the confederate, other participant or both children.

Salivary Cortisol Sampling

Basal levels of salivary cortisol were collected from home to ascertain the child’s afternoon baseline over three days using established methods (Corbett, Mendoza, Wegelin, Carmean, & Levine, 2008). The collection tubes were stored in a Trackcap™ (Aprex®, Union City, CA), containing a microelectronic cap that provides a precise timestamp when tubes were removed, which ensures adherence to the sampling protocol and confirmed time of sampling (Kudielka, Broderick, & Kirschbaum, 2003).

Cortisol Assay

The salivary cortisol assay was performed using a Coat-A-Count® radioimmunoassay kit (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Los Angeles, CA) modified to accommodate lower levels of cortisol in human saliva relative to plasma. Saliva samples, which had been stored at −20°C, were thawed and centrifuged at 3460 rpm for 15 minutes to separate the aqueous component from mucins and other suspended particles. The coated tube from the kit was substituted with a glass tube into which 100 μl of saliva, 100 μl of cortisol antibody (courtesy of Wendell Nicholson, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN), and 100 μl of 125I-cortisol were mixed. After incubation at 4°C for 24 hours 100 μl of normal rat serum in 0.1% PO4/EDTA buffer (1:50) and precipitating reagent (PR81) were added. The mixture was centrifuged at 3460 rpm for 30 minutes, decanted, and counted. Serial dilution of samples indicated a linearity of 0.99. Interassay coefficient of variation was 10.4%.

Dependent Variables

Social Behavior

The primary outcome variables of interest for characterizing social behavior were the transactional variables percentage of time engaged in Verbal Interaction, Cooperative Play and Self Play; secondary variables pertained to the percentage of Equipment Use (alone and with a group); and event variables which included Verbal Initiation and Verbal Rejection. As noted above, social motivation was characterized by the extent to which the participants were engaged in verbal interactions and cooperative play during solicited periods of time (T2 and T4).

Salivary cortisol

The primary outcome variable of interest for characterizing the stress response was salivary cortisol. Because salivary cortisol measurements are positive and skewed toward large values a log transformation was performed to achieve approximate normality; thus log-transformed values were used in all analysis. As noted in Figure 1, the peer interaction included four salivary cortisol samples taken 20 minutes apart for each subject: S1 – (baseline), S2 – (immediately post-play), S3 – (20 minutes post-play), and S4 – (40 minutes post play). Importantly, there is an approximate 20-minute lag from the time an event occurs until the change in cortisol can be detected in saliva (Kirschbaum & Hellhammer, 1989). For example, the S2 measurement taken immediately after the peer interaction is representative of the subject’s circulating cortisol levels at the beginning of the peer interaction while the S3 measurement is representative of the cortisol levels at the end of the peer interaction. All peer interactions were held in the afternoon between 13:00 and 16:00 for comparison to afternoon values from the diurnal study.

Independent Variables

Diagnosis was a primary independent variable included in all of the models. It was treated as a categorical variable with 2 levels (ASD, TD).

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and behavioral variables were compared between groups using Wilcoxon Rank-sum test. Cortisol profiles were scrutinized for children with ASD compared to age and gender-matched TD peers for the magnitude (stress response) and individual differences (responder status) in the level of cortisol as well potential associations with behavioral profile.

For the stress response to play, we compared changes in log cortisol at the playground for the two groups using mixed models, which included fixed effects diagnosis, time and diagnosis × time interaction, along with an autoregressive covariance structure to account for repeated measures at baseline (mean afternoon), novelty (S1), stress (S2) and stress/recovery(S3) for each subject. Parameters were estimated from this model and were used to compare group differences at each time point as well as change scores from baseline. Effect size calculations were conducted based on methods previously described (Nakagawa & Cuthill, 2007).

To classify the participants in each group based on stress response status, each participant was characterized by comparing cortisol values to stress to mean afternoon home values (stress value minus mean afternoon home value). Nonresponder was defined as MEAN (playground stress values) within MEAN (afternoon home values) ± 1.65× SD (afternoon home values), whereas responders were classified as MEAN (playground stress values) > 1.65 × SD (afternoon home values). These classifications were then used to associate responder status with diagnostic and social behaviors.

Spearman Rho correlations were conducted between the behavioral and cortisol variables.

RESULTS

The demographic information for the groups is presented in Table 1 pertaining to age, social communication and cognitive functioning.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Variable | ASD Mean (SD) | TD Mean (SD) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 10.34 (2.02) | 9.62 (1.67) | 0.172 |

| SCQ | 21.26 (6.92) | 2.52 (2.02) | <0.0001 |

| WASI Estimated IQ | 102.76 (24.44) | 119.03 (13.7) | 0.0023 |

| Verbal IQ | 108.6 (59.6) | 121.42 (15.26) | 0.0007 |

| Performance IQ | 109.78 (50.87) | 112.7 (13.96) | 0.0515 |

Note: Mean, SD = standard deviation. SCQ = Social Communication Questionnaire, WAIS = Wechsler Abbreviated Intelligence Scale, IQ = Intelligence Quotient.

Social Behavior

The behavioral results from the Peer Interaction paradigm are provided in Table 2. There were no significant differences between the groups during free play periods (T1 and T3). During unsolicited free play, children with ASD behaved quite similarly to their peers in terms of the frequency and duration of their verbal and social interactions. For example, the ASD children engaged in verbal interactions 53.7% and 61.7%, respectively during the two unsolicited play periods, and the TD children engaged 58.5% and 60.7% of the time.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics behavioral variables for solicited play:

| Segment | Behavioral Codes | ASD Mean (SD) | TD Mean (SD) | Effect Size | Association with cortisol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2 | Verbal Interaction | 76.01 (33.97) | 94.47 (10.73) | −25.26* | −.27* |

| T2 | Cooperative Play | 60.56 (37.07) | 71.31 (28.93) | −11.54* | −.27* |

| T2 | Verbal Initiation | 0 (0) | 0.22 (0.55) | −18.76 | ns |

| T2 | Verbal Rejection | 0.62 (1.23) | 0.16 (0.51) | 15.96 | ns |

| T4 | Verbal Interaction | 73.88 (35.74) | 89.34 (18.37) | −19.02* | −.27* |

| T4 | Cooperative Play | 63.33 (36.33) | 80 (22.8) | −19.38† | −.34** |

| T4 | Self-Play | 25.3 (30.72) | 10.94 (20.7) | 19.40** | .34** |

| T4 | Equipment Play | 23.26 (30.45) | 14.22 (24.34) | 11.72 | .39** |

| T4 | Verbal Rejection | 0.5 (0.86) | 0.25 (0.62) | 10.92 | .27* |

| T4 | Equipment Group | 62.2 (37.51) | 77.41(23.11) | −17.19 | −.31** |

Note: T1 – T4 = Time followed by five minute periods. SD = standard deviation. P value was computed based on Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Interaction and Play variables are percentages of time engaged in activity whereas Verbal Initiation and Rejection are frequency variables. Responder Status Cortisol

= correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

= Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

= trend 0.06.

However, during periods of solicited play by the confederate (T2 and T4), several differences were observed (see Table 2). In general, the TD group engaged in more verbal interactions, cooperative play, and verbal initiation thereby suggesting more social motivation to engage with others. For example, the TD group engaged in verbal interactions during periods of solicited play 94.5% and 89.3% of the time, whereas the ASD group engaged 76% and 73.9% of the time. Additionally, the ASD group demonstrated more self-play and less cooperative play with peers during these periods of time. The between-group differences remain when controlling for VIQ for verbal interactions, verbal initiation, self-play and a trend for cooperative play. The results support the hypothesis that the ASD group shows less social motivation than the TD group during periods of solicited play.

Cortisol

Stress

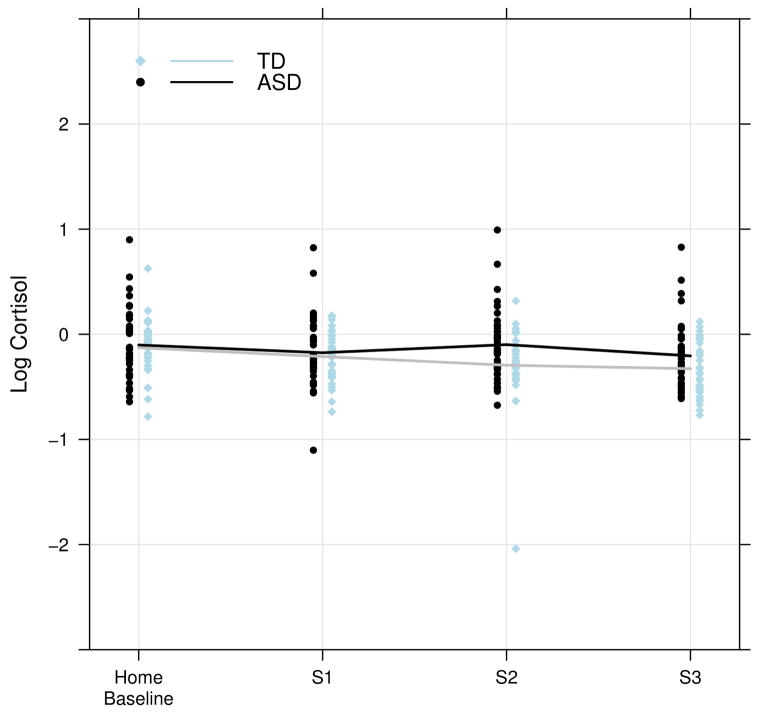

For the stress paradigm, there were no significant differences related to the magnitude of the cortisol values between the groups at baseline or for the novelty (p = 0.91) or recovery (p = 0.31) values. However, there was a trend (p = 0.06) for the stress measure when compared to the average afternoon baseline values showing higher levels of cortisol for the ASD group (see Figure 2). The marginal findings are similar to previous reports of increased cortisol in response to play with peers compared to the typically developing group (Corbett et al., 2010).

Figure 2.

Cortisol Values during Peer Interaction with Home Afternoon Mean as Baseline

Responder Status

The within group approach for quantifying cortisol responder status stratified members in each group based on mean cortisol levels at the playground and baseline samples, which resulted in 14 ASD responders and 14 TD participants. Subsequently, we aimed to determine if there was a difference between responder status (responder versus nonresponder) and clinical status (ASD versus TD). The chi-square test of independence had a p-value of 0.39, indicating responder status and clinical status are two different classifications and thereby are independent.

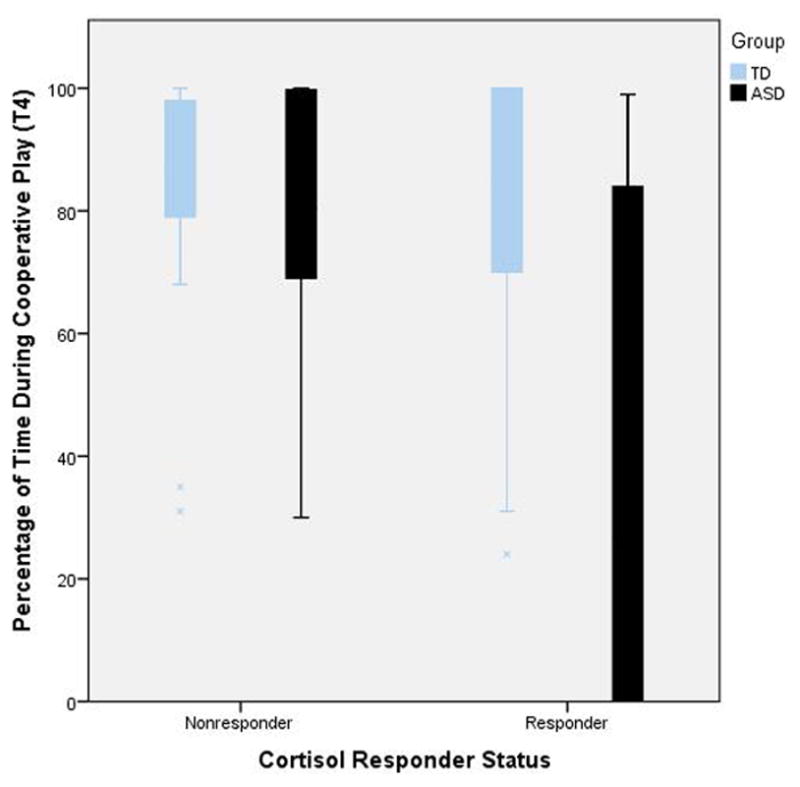

In order to examine the significant variability in social behavior in the ASD responder group (see Figure 3), we examined the relationship with and without adjusting by IQ to determine if this contributed to the variability. We conducted a 2×2 ANOVA with group (ASD and TD) and Responder Status (Responder and Nonresponder) and social motivation variables (cooperative play/verbal interaction). The results are presented in Table 3, indicating a significant difference in ASD Responders for cooperative play and verbal interactions. The findings remain even when controlling for verbal IQ (as shown in lower half of the table).

Figure 3.

Relationship between Cooperative Play and Responder Status between the Groups

Table 3.

| ANOVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2 | ASD | TD | p | |

| Cooperative play | Non responder | 71.56 | 71.07 | 0.96 |

| Responder | 39.44 | 70.71 | 0.012 | |

| Verbal Interaction | Non responder | 91.01 | 93.79 | 0.59 |

| Responder | 67.56 | 95.9 | <0.0001 | |

| T4 | ||||

| Cooperative Play | Non responder | 75.78 | 80.47 | 0.62 |

| Responder | 39.57 | 77.5 | 0.0007 | |

| Verbal Interaction | Non responder | 84.87 | 89.47 | 0.61 |

| Responder | 55.3 | 88.36 | 0.002 | |

| ANCOVA: adjusted by Verbal IQ | ASD | TD | p | |

| T2 | ||||

| Cooperative play | Non responder | 75.6 | 76.4 | 0.94 |

| Responder | 45.1 | 74.46 | 0.04 | |

| Verbal Interaction | Non responder | 87.07 | 90.05 | 0.59 |

| Responder | 68.36 | 92.76 | 0.002 | |

| T4 | ||||

| Cooperative play | Non responder | 60.26 | 64.6 | 0.62 |

| Responder | 28.34 | 64.21 | 0.002 | |

| Verbal Interaction | Non responder | 79.95 | 83.31 | 0.06 |

| Responder | 64.29 | 85.74 | 0.02 | |

Associations between social functioning and stress

Potential relationships were examined between social behavior during solicited cooperative play and physiological arousal using Pearson product-moment correlations. Several relationships were identified (Table 2). Specifically, elevated cortisol was negatively correlated with behaviors reflecting social motivation, such as verbal interactions, cooperative play, and group equipment play, and positively correlated with self-play and equipment play alone. In other words, individuals that showed a behavioral pattern of increased social motivation exhibited decreased cortisol levels during solicited play. As shown in Figure 3, the cortisol and social behavior association is largely driven by the ASD group such that the children with higher cortisol engage in less social interaction. The findings support the proposed reciprocal association between social behavior during solicited play and cortisol levels.

To more carefully examine within-group associations between the demographic, cognitive, behavioral and cortisol variables, separate Spearman correlations were conducted for the ASD and TD groups and results are presented in Table 4. For example, the ASD group showed associations between VIQ and group play (verbal interactions and equipment play with group) suggesting that better verbal cognition contributes to enhanced verbal exchange with peers. In the TD group, VIQ was negatively associated with self-play and equipment use alone.

Table 4.

Within Group Spearman Correlations

| ASD only | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral | Age | FSIQ | VIQ | PIQ | Stress - Home Afternoon |

| T2 Cooperative Play | −0.10 | −0.01 | 0.09 | −0.18 | 0.19 |

| T2 Verbal Interaction | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.24 | −0.03 | 0.12 |

| T2 Equipment Use | 0.13 | 0.09 | −0.17 | 0.13 | 0.07 |

| T2 Equipment Use Group | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| T2 Self-Play | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.14 |

| T2 Verbal Initiation | |||||

| T2 Verbal Rejection | 0.17 | 0.00 | −0.15 | 0.22 | −0.08 |

| TD only | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral | Age | FSIQ | VIQ | PIQ | S15 - Home Afternoon |

| T2 Cooperative Play | −0.02 | 0.23 | 0.10 | 0.09 | −0.04 |

| T2 Verbal Interaction | 0.14 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.27 |

| T2 Equipment Use | 0.09 | −0.31 | −0.20 | −0.32 | 0.11 |

| T2 Equipment Group | −0.13 | −0.08 | 0.03 | −0.05 | −0.03 |

| T2 Self-Play | 0.06 | −0.34 | −0.23 | −0.17 | 0.10 |

| T2Verbal Initiation | −0.17 | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.20 |

| T2VerbalRejection | −0.06 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.20 |

Note: ASD = autism spectrum disorder; TD = typically developing. T = time; FSIQ = Full Scale Intelligence Quotient; VIQ = Verbal IQ; PIQ = Performance IQ. Stress – Home afternoon = cortisol levels during peer interaction minus average afternoon cortisol levels.

Since there were significant differences between the groups based on cognitive functioning, we calculated Spearman partial correlations between behavioral variables and cortisol levels while controlling for IQ and age. For the Age and Performance IQ (PIQ), the correlations were weak ranging from ρ 0.02 (Cooperative Play) to ρ 0.16 (Self-Play). Similarly, the age and Verbal IQ (VIQ) correlations with the social behavioral variables were also weak ranging from ρ = 0.04 (Cooperative play) to 0.14 (Self-Play).

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we carefully evaluated the social interaction patterns during natural play conditions, the profile of cortisol during baseline and social exchanges, and the interplay between these biobehavioral profiles in children with ASD. The peer interaction paradigm is designed to evaluate social engagement during periods of solicited and unsolicited free play through the use of a confederate. During periods of free play, there were no behavioral differences between children with ASD and TD peers in regards to verbal exchanges including the duration of interactions, as well as the number of verbal initiations or rejections. Moreover, there were no differences in the type of play including cooperative, self or equipment play between the groups. Thus, without the confederate soliciting them to participate in an activity or conversation, children with ASD behaved quite similarly to their peers in regards to the frequency and duration of their verbal and social interactions. For example, during the free play periods, the ASD and TD groups equally engaged in conversation approximately 50% of the time.

However, this was in stark contrast to the solicited play periods when several differences emerged. The TD group engaged in significantly more verbal exchanges consisting of to-and-fro conversation with their peers. While both groups showed more verbal interactions compared to the free play periods, the TD group engaged roughly 92% of the time whereas the ASD group engaged in conversation with peers 74% of the time. They also demonstrated fewer verbal initiations and a trend for more verbal rejections during the initial solicited period. The level of play skills in another child (Tanta, Deitz, White, & Billingsley, 2005) can influence the number of initiations and responses; however, all of the children played with not only a TD child but also a trained confederate who exhibited advanced play skills. Regarding the type of play, the ASD group participated in more self-play and relatively less cooperative play during the solicited play period with toys. Taken together, the findings provide support for the hypothesis that children with ASD exhibit diminished social motivation to engage with others especially when asked.

While it may be expected to see differences between children with and without ASD in the amount of verbal or social exchange, the findings reveal important underlying observations based on the behavior of the confederate. When the confederate did not invite the two other children to play, both groups behaved strikingly similar. And when the primary social agent (confederate) temporally disengaged from the play, the children reverted back to their initial level of more independent activities. Yet, when even a single bid for play was made, the level of verbal and social exchange rose dramatically; explicitly a 30% increase for the ASD and 54% increase for the TD group. In other words, both children with and without ASD benefited from the invitation to play by another child. Thus, it highlights the pivotal role that a peer can have in fostering engagement with others whether the child is typically developing or has ASD (Corbett, et al., 2010; DiSalvo & Oswald, 2002; Odom & Strain, 1984). While the initiation of a social agent is necessary for social exchange, it is not sufficient. Despite the increase in participation when summoned by the confederate, the ASD children still showed less social communication compared to the TD children. Nevertheless, the scaffolding that the solicited exchanges provide for the children with ASD underscores the importance of peer-mediated interactions in natural settings in facilitating engagement (Kasari, Rotheram-Fuller, Locke, & Gulsrud, 2012; Paul, 2008) and the inclusion of trained peers in interventions aimed at improving social communication skills (Corbett et al., 2011; Corbett et al., in press; DiSalvo & Oswald, 2002; Kasari, et al., 2012; Odom & Strain, 1984).

An important point that must not be overlooked is the fact that the significant differences in social play between the groups center on verbally-mediated interactions. This observation highlights the important influence of language abilities on reciprocal social exchange, especially with peers. The results of the current study show that verbal cognitive ability contributes to the level of reciprocal social exchange with peers, but it is not sufficient. As reflected in the recent change in the diagnostic manual (APA, 2013), the social and communication profile of individuals with ASD are interdependent. Therefore, when examining social functioning in ASD, verbal ability is an imperative consideration.

The current study was conducted on a much larger (2-fold) playground than previously reported. There is evidence that smaller playgrounds with greater spatial density increase interaction in children with typical development (Frost, Shin, & Jacobs, 1997), but may reduce engagement in children with autism (Hutt & Vaizey, 1966). However, a more recent study suggests that the configuration of the playground, rather than size, is a more relevant consideration for children with ASD such that a centralized, self-contained circuit of play equipment and toys can facilitate interaction (Yuill, et al., 2007), which is characteristic of the small and larger playground settings employed. Although it is not known what the actual social stress profile of children with ASD might be when engaged with peers on a standard school playground with many more children and social demands, the stress is likely to be even greater. By increasing the number of peers on a playground, children with ASD may become increasingly more withdrawn whereas TD children may benefit from the greater potential of social partners and interaction opportunities.

One of the primary aims of the study was to assess the physiological effects of exposure to play with peers in a natural playground setting. As predicted, there were no significant differences between the groups at baseline, during the initial exposure, or for the recovery after the play stressor. However, there was a trend for increased arousal as measured by cortisol in the ASD group compared to the TD group that showed less responsivity. Increased cortisol in response to play with novel peers is similar to previous reports (Schupp, et al., 2013; Schutt et al., 1997). However, in the earlier studies there was an interaction age effect, which was not found in the current results despite the ages in current sample (ASD = 10.3, TD = 9.6) being similar to the former groups (ASD = 10, TD = 9.9).

Another consideration to explore in the cortisol expression is the variability. As illustrated in Figure 2, there was a broad range of responsiveness particularly in the ASD group. Thus, a deeper characterization of the cortisol profile was undertaken to identify stress responders and nonresponders. Baseline mean and playground stress levels were used to define responder status to examine individual differences in salivary cortisol and the degree to which such values were associated with domains of social functioning. Within this context it was hypothesized that children with ASD would show distinct biobehavioral profiles based on their social functioning (e.g., cooperative play) and salivary cortisol. The prediction was confirmed as significant associations were observed between the participant’s level of social engagement and cortisol levels.

Responder status was negatively correlated with verbal interactions, cooperative play, and equipment play as a group and positively correlated with self-play and equipment play alone. The findings for the participants with ASD show a pattern of higher cortisol response which was associated with reduced verbal exchange and social engagement, as well as more autonomous play. As shown in Figure 3, children with ASD that are responders tend to engage in less social play; however, this association was not observed in children with TD. Thus, it suggests that the proportion of children with ASD who demonstrate elevated cortisol also show diminished cooperative play. While the direction of the relationship is unclear, children with ASD that are responders show diminished motivation to socially interact with others. It is plausible that the level of stress may modulate the extent to which the child is able to participate in social play. While a certain level of arousal is necessary to engage with others, too much arousal, which is seen in the performance of demanding tasks, may inhibit optimal performance (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908). In this context, engaging with peers on a playground is likely a highly complex task and thereby, may result in enhanced arousal for some children with ASD, the extent to which may facilitate or interfere with social interaction.

Strengths of the study include a well-characterized, relatively large sample of children with ASD, utilization of state-of-the-art video and audio capture technology, and the use of a validated protocol that studies children in a natural, age-appropriate, play setting. Despite these strengths, limitations remain which include the utilization of a single physiological measure, cortisol. Although we examine multiple samples per child across baseline and protocol conditions, the inclusion of additional physiological measures, such as heart rate variability (Daluwatte et al., 2012) or respiratory sinus arrhythmia (Patriquin, Scarpa, Friedman, & Porges, 2013) may complement the current research and serve as a more immediate, real-time proxy of arousal. Additionally, the study population was unmedicated which significantly reduced confounding factors in cortisol assays. However, considering that a large percentage of the ASD population is prescribed medication ((Mandell et al., 2008), the findings may not apply to children receiving pharmaceutical treatment.

In summary, the current study reveals biobehavioral profiles related to stress and social engagement with peers during natural play in children with ASD. While children with and without ASD engage in similar patterns of independent play they both show an increase in verbal and social exchange when play is solicited by another child highlighting the pivotal role that peers have in social interaction. Even so, significant differences emerge during periods of cooperative play in the duration and type of play. Children with ASD also tend to show higher levels of cortisol in response to social interaction with other children. Even so, it must be emphasized that stress responsivity in ASD is on a continuum with higher cortisol responders in the current study showing less social motivation and more self-play. Additional research is needed to determine if the observed elevations in cortisol in each child reflect an underlying state of heightened arousal or an enhanced reactivity to social engagement, or as is the case for many biobehavioral factors in ASD – there may be a spectrum of stress responsivity.

Key points.

Children with and without ASD behave similarly during unsolicited play

Social invitation by peer to play facilitates interaction for both groups but to a lesser degree in ASD, peer is pivotal

Diminished social motivation in ASD evidenced by fewer verbal interactions and initiations and more self-play

Children with ASD tend to show higher cortisol during play; however, there is significant variability

Children with ASD characterized as cortisol responders showed less social motivation

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health R01 MH085717 awarded to Blythe Corbett and a National Institute of Child Development Grant P30 HD15052 to Vanderbilt Kennedy Center (VKC). The authors thank Eric Allen (VUMC Hormone Assay and Analytical Services Core, supported by NIH grants DK059637 and DK020593) for validation and completion of the cortisol assays.

The study was supported by CTSA award No. UL1TR000445 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

The authors have declared that they have no potential or competing conflicts of interest.

References

- APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) [Google Scholar]

- APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washinton, D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. (DSM-5) [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S. Minblindness: an essay on autism and theory of mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bellini S. The development of social anxiety in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2006;21(3):138–145. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher J, Wolfberg P. Play. Autism. 2003;7(4):339–346. doi: 10.1177/1362361303007004001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP, Rosso J, Garguilo J. Validity of self-report measures of girl's pubertal status. Child Development. 1987;58:829–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canivez GL, Konold TR, Collins DM, Wilson G. Construct Validity of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence and Wide Range Intelligence Test: Convergent and Structural Validity. School Psychology Quarterly. 2009;24(4):252–265. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler S, Charman T, Baird G, Simonoff E, Loucas T, Meldrum D, et al. Validation of the social communication questionnaire in a population cohort of children with autism spectrum disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(10):1324–1332. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31812f7d8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier C, Kohls G, Troiani V, Brodkin ES, Schultz RT. The social motivation theory of autism. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16(4):231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church C, Alisanski S, Amanullah S. The social, behavioral, and academic experiences of children with Asperger syndrome. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilties. 2000;15(1):12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett BA, Gunther JR, Comins D, Price J, Ryan N, Simon D, et al. Brief report: theatre as therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(4):505–511. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1064-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett BA, Mendoza S, Wegelin JA, Carmean V, Levine S. Variable cortisol circadian rhythms in children with autism and anticipatory stress. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 2008;33(3):227–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett BA, Schupp CW, Lanni KE. Comparing biobehavioral profiles across two social stress paradigms in children with and without autism spectrum disorders. Mol Autism. 2012;3(1):13. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett BA, Schupp CW, Simon D, Ryan N, Mendoza S. Elevated cortisol during play is associated with age and social engagement in children with autism. Mol Autism. 2010;1(1):13. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett BA, Swain DS, Coke C, Simon D, Newsom C, Houchins-Juarez N, et al. Improvement in social deficits in autism spectrum disorders using a theatre-based, peer-mediated intervention. Autism Research. doi: 10.1002/aur.1341. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daluwatte C, Miles JH, Christ SE, Beversdorf DQ, Takahashi TN, Yao G. Atypical Pupillary Light Reflex and Heart Rate Variability in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;43(8):1910–1925. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1741-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(3):355–391. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiSalvo C, Oswald D. Peer-mediated interventions to increase the social interaction of children with autism: Consideration of peer expectancies. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities. 2002;17(4):198–207. [Google Scholar]

- Frost JL, Shin D, Jacobs P. Physical environmnets and children's play. In: Spodek B, editor. Multiple perspectives on play in early childhood education. New York: SUNY; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hennessey JW, Levine S. Stress, arousal, and the pituitary-adrenal system: a psychoendocrine hypothesis. Vol. 8. New York: Academic Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, Cullinan WE. Neurocircuitry of stress: central control of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20(2):78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey E, Leekam S, Turner M, McConachie H. Repetitive behaviour and play in typically developing children and children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(6):1107–1115. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey N, Symes W. Peer interaction patterns among adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders (ASDs) in mainstream school settings. Autism. 2011;15(4):397–419. doi: 10.1177/1362361310387804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutt C, Vaizey MJ. Differential effects of group density on social behavior. Nature. 1966;(209):1371–1372. doi: 10.1038/2091371a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child. 1943;2:217–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E, Locke J, Gulsrud A. Making the connection: randomized controlled trial of social skills at school for children with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53(4):431–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Hellhammer DH. Salivary cortisol in psychobiological research: an overview. Neuropsychobiology. 1989;22(3):150–169. doi: 10.1159/000118611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott F, Dunlop AW, Mackay T. Living with ASD: how do children and their parents assess their difficulties with social interaction and understanding? Autism. 2006;10(6):609–617. doi: 10.1177/1362361306068510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasny L, Williams BJ, Provencal S, Ozonoff S. Social skills interventions for the autism spectrum: essential ingredients and a model curriculum. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2003;12(1):107–122. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(02)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, Broderick JE, Kirschbaum C. Compliance with saliva sampling protocols: electronic monitoring reveals invalid cortisol daytime profiles in noncompliant subjects. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(2):313–319. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000058374.50240.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanni KE, Schupp CW, Simon D, Corbett BA. Verbal ability, social stress, and anxiety in children with Autistic Disorder. Autism. 2012;16(2):123–138. doi: 10.1177/1362361311425916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopata C, Volker MA, Putnam SK, Thomeer ML, Nida RE. Effect of social familiarity on salivary cortisol and self-reports of social anxiety and stress in children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38(10):1866–1877. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0575-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Jr, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, et al. The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(3):205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons D, Mason WA, Mendoza SP. Beyond the ethogram: Transactional analysis of behavior in primate social interchanges. American Journal of Primatology. 1990;20:209. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons D, Mendoza S, Mason W. Sexual segregation in squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus): A transactional analysis of adult social dynamics. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1992;106(4):323–330. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.106.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, Morales KH, Marcus SC, Stahmer AC, Doshi J, Polsky DE. Psychotropic medication use among Medicaid-enrolled children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):e441–448. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason JW. A review of psychoendocrine research on the pituitary-adrenal cortical system. Psychosom Med. 1968;30(5, Suppl):576–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W, Long D, Mendoza S. Temperment and Mother-Infant Conflict in Macaques: A Transactional Analysis. In: Mendoza WMS, editor. Primate Social Conflict. Albany, NY: SUNY Press; 1993. pp. 205–227. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza SP, Mason W. Behavioral and endocrine consequences of heterosexual pair formation in squirrel monkeys. Physiol Behav. 1989;46(4):597–603. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modahl C, Green L, Fein D, Morris M, Waterhouse L, Feinstein C, et al. Plasma oxytocin levels in autistic children. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;43(4):270–277. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00439-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S, Cuthill IC. Effect size, confidence interval and statistical significance: a practical guide for biologists. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2007;82(4):591–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noldus. The Observer XT. Vol. 10.5. Wageningen, The Netherlands: Noldus Information Technology; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Odom SL, Strain PS. Peer-mediated approaches to promoting children's social interaction: a review. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1984;54(4):544–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1984.tb01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patriquin MA, Scarpa A, Friedman BH, Porges SW. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia: a marker for positive social functioning and receptive language skills in children with autism spectrum disorders. Dev Psychobiol. 2013;55(2):101–112. doi: 10.1002/dev.21002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul R. Interventions to improve communication in autism. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2008;17(4):835–856. ix–x. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini AD, Smith PK. Physical activity play: the nature and function of a neglected aspect of playing. Child Dev. 1998;69(3):577–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: reliability, validity and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1988;17(2):117–131. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J, Inhelder B. In: The psychology of the child. Weaver H, translator. New Yor, NY: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Bailey A, Lord C. The Social Communication Questionnaire. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schupp CW, Simon D, Corbett BA. Cortisol Responsivity Differences in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders During Free and Cooperative Play. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1790-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutt WA, Jr, Altenbach JS, Chang YH, Cullinane DM, Hermanson JW, Muradali F, et al. The dynamics of flight-initiating jumps in the common vampire bat Desmodus rotundus. J Exp Biol. 1997;200(Pt 23):3003–3012. doi: 10.1242/jeb.200.23.3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanta KJ, Deitz JC, White O, Billingsley F. The effects of peer-play level on initiations and responses of preschool children with delayed play skills. Am J Occup Ther. 2005;59(4):437–445. doi: 10.5014/ajot.59.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky LS. Mind in society: The development of higher mental processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Oswald D, Ollendick T, Scahill L. Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(3):216–229. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing L, Gould J. Severe impairments of social interaction and associated abnormalities in children: epidemiology and classification. Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1979;9(1):11–29. doi: 10.1007/BF01531288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yerkes RM, Dodson JD. The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1908;18:459–482. [Google Scholar]

- Yuill N, Strieth S, Roake C, Aspden R, Todd B. Brief report: designing a playground for children with autistic spectrum disorders--effects on playful peer interactions. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(6):1192–1196. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0241-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]