Abstract

Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to numerous health problems, including neurological and muscular degeneration, cardiomyopathies, cancer, diabetes, and pathologies of aging. Severe mitochondrial defects can result in childhood disorders such as Leigh syndrome, for which there are no effective therapies. We found that rapamycin, a specific inhibitor of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway, robustly enhances survival and attenuates disease progression in a mouse model of Leigh syndrome. Administration of rapamycin to these mice, which are deficient in the mitochondrial respiratory chain subunit Ndufs4 [NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 4], delays onset of neurological symptoms, reduces neuroinflammation, and prevents brain lesions. Although the precise mechanism of rescue remains to be determined, rapamycin induces a metabolic shift toward amino acid catabolism and away from glycolysis, alleviating the buildup of glycolytic intermediates. This therapeutic strategy may prove relevant for a broad range of mitochondrial diseases.

Leigh syndrome is a clinically defined disease resulting from genetic defects that disrupt mitochondrial function. It is the most common childhood mitochondrial disorder, affecting 1 in 40,000 newborns in the United States (1). Leigh syndrome is characterized by retarded growth, myopathy, dyspnea, lactic acidosis, and progressive encephalopathy primarily in the brainstem and basal ganglia (2, 3). Patients typically succumb to respiratory failure from the neuropathy, with average age of death at 6 to 7 years (1).

We recently observed that reduced nutrient signaling, accomplished by glucose restriction or genetic inhibition of mTOR, is sufficient to rescue short replicative life span in several budding yeast mutants defective for mitochondrial function (4), including four mutations associated with human mitochondrial disease (fig. S1). These observations led us to examine the effects of rapamycin, a specific inhibitor of mTOR, in a mammalianmodel of Leigh syndrome, the Ndufs4 knockout (Ndufs4−/−) mouse (5). Ndufs4 encodes a protein involved in assembly, stability, and activity of complex I of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) (6, 7). Ndufs4−/− mice show a progressive neurodegenerative phenotype characterized by lethargy, ataxia, weight loss, and ultimately death at a median age of 50 days (5, 8). Neuronal deterioration and gliosis closely resemble the human disease, with primary involvement of the vestibular nuclei, cerebellum, and olfactory bulb.

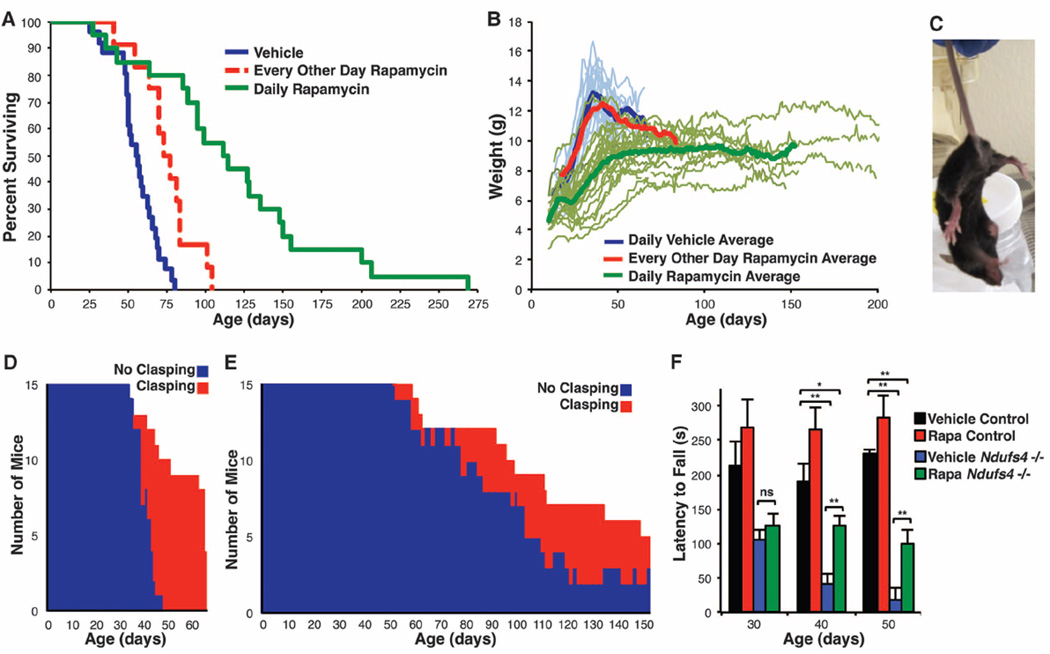

We first examined the effects of delivering rapamycin (8 mg/kg) every other day by intraperitoneal injection beginning at weaning [approximately postnatal day 20 (P20)]. This treatment reduces mTOR signaling in wild-type mice (9) and provided significant increases in median survival of male (25%) and female (38%) knockout mice (Fig. 1A). A slight reduction in maximum body size and a delay in age of disease onset were also observed (Fig. 1B and fig. S2). Although these results showed that Ndufs4−/− mice benefit from rapamycin treatment, we noted that by 24 hours after injection, rapamycin levels in blood were reduced by more than 95% (fig. S3). We therefore performed a follow-up study delivering rapamycin (8 mg/kg) daily by intra-peritoneal injection starting at P10, which resulted in blood levels ranging from >1800 ng/ml immediately after injection to 45 ng/ml trough levels (fig. S3). For comparison, an encapsulated rapamycin diet that extends life span in wild-type mice by about 15% achieves steady-state blood levels of about 60 to 70 ng/ml, and trough levels between 3 and 30 ng/ml are recommended for patients receiving rapamycin (10). In the daily-treated cohort, we observed a striking extension of median and maximum life span; the longest-lived mouse survived 269 days. Median survival of males and females was 114 and 111 days, respectively (fig. S2C).

Fig. 1. Reduced mTOR signaling improves health and survival in a mouse model of Leigh syndrome.

(A) Survival of the Ndufs4−/− mice was significantly extended by rapamycin injection every other day; life span more than doubled with daily rapamycin treatment (log-rank P = 0.0002 and P < 0.0001, respectively). (B) Body weight plots of Ndufs4−/− mice. (C) Representative forelimb clasping behavior, a widely used sign of neurological degeneration. Clasping involves an inward curling of the spine and a retraction of forelimbs (shown here) or all limbs toward the midline of the body. (D and E) Clasping in vehicle-treated (D) and daily rapamycin-treated (E) Ndufs4−/− mice as a function of age. A total of 15 mice were observed for clasping daily for each treatment. Age of onset of clasping behavior is significantly delayed in rapamycin-treatedmice (**P<0.001 by log-rank test). (F) Ndufs4−/− mice show a progressive decline in rotarod performance that is rescued by rapamycin (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, Student’s t test; error bars are ± SEM). (See also fig. S5, which indicates replicate numbers.)

Vehicle-injected knockout mice first displayed neurological symptoms around P35, coinciding with a body weight peak (Fig. 1, B to D, and fig. S2D). After this point, disease symptoms progressively worsened and weight declined. Daily rapamycin treatment dampened developmental weight gain and prevented the progressive weight loss phenotype (Fig. 1B and fig. S2E). This effect was robust, even among mice from the same litter (fig. S4). Incidence and severity of clasping, a commonly reported and easily scored phenotype that progresses with weight loss and neurological decline, was also greatly attenuated in rapamycin-treated knockouts (Fig. 1, C to E). Performance in a rotarod assay, which measures balance, coordination, and endurance, was assessed in a separate cohort of mice. Vehicle-treated knockout mouse performance worsened as the disease progressed, whereas rapamycin-treated knockout mice maintained their performance with age (Fig. 1F and fig. S5). Dyspnea, previously observed in vehicle-treated knockout mice (5), was not observed in the mice injected daily with rapamycin.

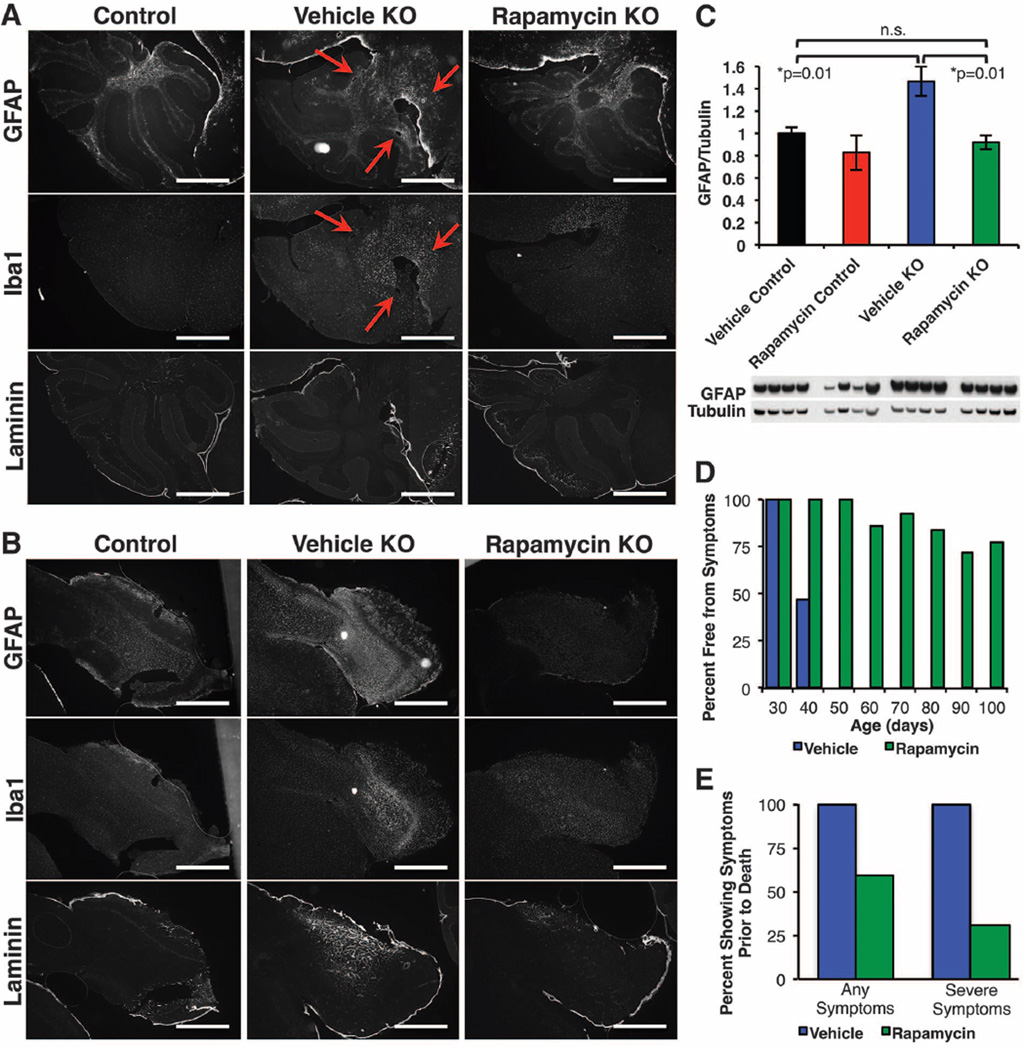

Rapamycin-treated knockout mice also did not develop the neurological lesions associated with this disease (red arrows in Fig. 2, A and B; see also fig. S6). The lesions, characterized by astrocyte activation and glial reactivity [detected by glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and Iba1 staining, respectively] were detectable in all vehicle-treated knockout mice over 50 days of age (5).We were unable to detect lesions in the cerebellum of age-matched rapamycin-treated knockout mice. GFAP, Iba1, and laminin (a marker of neovascularization) were markedly increased in olfactory bulbs of vehicle-treated but not in rapamycin-treated knockout mice (Fig. 2B and fig. S6). Rapamycin did not affect GFAP, Iba1, or laminin levels in wild-type mice (fig. S6). Western blotting for GFAP using whole-brain lysates from ~50-day-old mice revealed a significant increase in GFAP in knockout mice that was attenuated by rapamycin (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, no lesions were detected in 100-day-old and 268-day-old rapamycin-treated knockout mice (fig. S7). Overall, the percentage of mice showing neurological symptoms was much reduced at every age point after P35 in rapamycin-treated knockout mice, with about half never exhibiting overt signs of neurological disease before death (Fig. 2, D and E).

Fig. 2. Rapamycin reduces neurological disease in Ndufs4−/− mice.

(A) Representative cerebellar staining for neurological lesions in 55- to 60-day-old mice. All vehicle-treated mice showed glial activation and lesions at this age, whereas lesions were not detected in age-matched daily rapamycin-treated mice (n = 6; scale bars, ~500 µm) (see also figs. S6 and S7). (B) Representative olfactory bulb staining shows activation of glia by GFAP staining and neovascularization by laminin staining in vehicle-treated knockout (KO) mice and a robust attenuation in rapamycin-treated KO mice (n = 6 per treatment; scale bars, ~500 µm). (C) Western blotting of whole-brain lysates from a separate cohort of mice shows increased GFAP in vehicle KO mice and rescue to control levels by rapamycin (*P < 0.05, Student’s t test; error bars are ± SEM). (D and E) The percentage of living mice showing neurological symptoms is greatly reduced by daily rapamycin treatment (D), as is the number of mice showing neurological symptoms at the time of death (E).

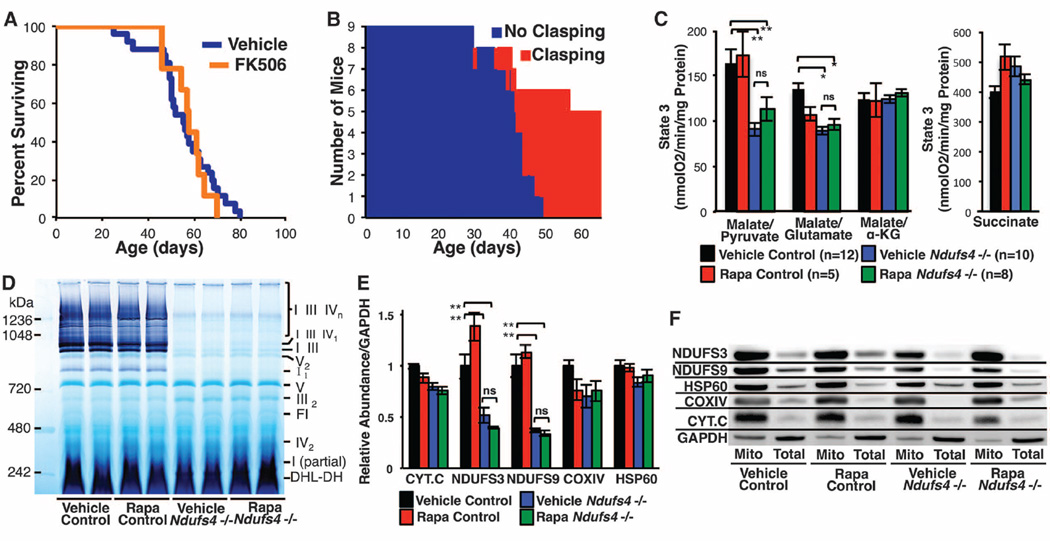

Given the pleiotropic effects of mTOR inhibition [reviewed in (11, 12)], we sought to identify downstream mechanisms associated with attenuation of mitochondrial disease. Rapamycin has well-documented immune-modulatory effects, so we first considered that the benefit might arise from reduced neuroinflammation. To test this model, we treated mice with FK-506 (tacrolimus), a clinically approved immunosuppressive drug that binds the same target as rapamycin, FKBP12, but inhibits calcineurin signaling rather than mTOR (13). FK-506 did not affect disease onset or progression (Fig. 3, A and B, and fig. S8), indicating that neither immunosuppression nor off-target disruption of calcineurin by binding of FKBP12 are likely to account for the effects of rapamycin. We next considered that rapamycin might improve mitochondrial function by increasing macroautophagy, removing the least functional components of the mitochondrial network. Although we were able to detect evidence of induction of autophagy in the liver and brain of rapamycin-treated mice (fig. S9), there was no corresponding rescue of mitochondrial function (Fig. 3C and fig. S10). Complex I assembly and stability, assessed by blue native gel electrophoresis, were also unaltered by rapamycin (Fig. 3D and fig. S11), as were levels and localization of ETC proteins (Fig. 3E and F, and fig. S12). We found no evidence for induction of HSP60, a component of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response, either by NDUFS4 loss or by rapamycin (Fig. 3F and fig. S12).

Fig. 3. Rapamycin does not substantially alter mitochondrial function or complex I assembly.

(A and B) FK-506 delivered at the highest tolerated dose (see fig. S8) failed to enhance survival (A) or attenuate disease (B) in Ndufs4−/− mice. (C) Rapamycin has no observed effect on respiratory activity or complex I deficiency of mitochondria isolated from ~50-day-old Ndufs4−/− mice; n = 4 to 6 mice per data point. (see also fig. S10). (D) Native-in-gel activity assays reveal that rapamycin does not influence assembly or stability of complex I (see also fig. S11). (E and F) Complex I subunits (NDUFS3 and NDUFS9) are significantly reduced in Ndufs4−/− mice, and rapamycin has no effect on their total levels (F) or subcellular localization (E) in brain. Levels of other mitochondrial proteins (cytochrome c, the complex IV subunit COXIV, and HSP60) are independent of both Ndufs4 genotype and treatment (see also fig. S9). *P < 0.05,**P < 0.005, Student’s t test; ns, not significant. Error bars are ±SEM.

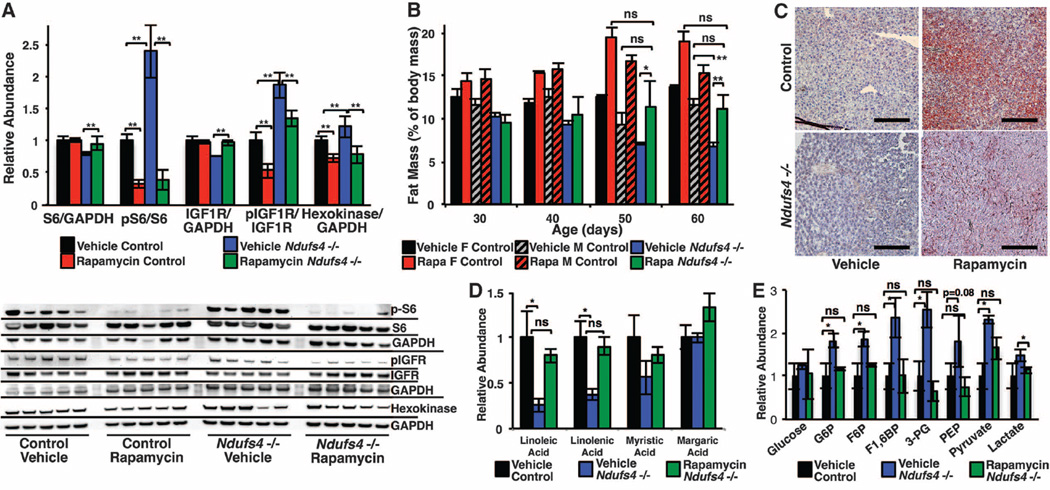

As a central coordinator of nutrient sensing and growth, mTOR regulates metabolism by integrating levels of amino acids at the lysosome, energetic sensing by adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase (AMPK), and extracellular signals through insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) (11, 14). We reasoned that loss of NDUFS4 might perturb metabolic signaling and affect mTOR activity. Consistent with this idea, phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6, a target of mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling, was significantly increased in the brains of knockout mice (Fig. 4A), and rapamycin reduced phosphorylation of S6 in both wild-type and knockout mice. IGF1 receptor (IGF1R) phosphorylation was also increased in Ndufs4−/− mice and reduced by rapamycin (Fig. 4A). Whole-body quantitative magnetic resonance revealed a progressive loss in body fat in the Ndufs4−/− mice that was ameliorated by daily rapamycin injections (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, Oil Red O staining and metabolomic analysis of liver indicated that knockout mice had a marked deficiency in liver fat droplets and free fatty acids that was partially rescued by rapamycin (Fig. 4, C and D, and fig. S13). Whole-brain metabolomics of 30-day-old mice revealed an abnormal metabolic profile in the Ndufs4−/− mice that included an accumulation of pyruvate, lactate, and all detected glycolytic intermediates, consistent with clinical reports of Leigh syndrome (2, 15) (Fig. 4E and table S1). The metabolomic signature of the Ndufs4−/− mouse brain includes a decrease in free amino acids, free fatty acids, nucleotides, and products of nucleotide catabolism, increased oxidative stress markers, and reduced levels of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and dopamine (fig. S14 and table S1). Rapamycin rescued many of these metabolomic defects associated with NDUFS4 deficiency, including levels of GABA, dopamine, and free fatty acids. Increased amino acids, metabolites of amino acid and nucleotide catabolism, and free fatty acids accompanied the decrease in glycolytic intermediates, whereas markers of oxidative stress were unchanged. Moreover, hexokinase—the first enzyme in glycolysis—was increased in Ndufs4−/− mice and reduced by rapamycin in knockout and control mice, consistent with the decrease in glycolytic intermediates (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4. Ndufs4−/− mice exhibit mTOR activation and metabolic defects that are suppressed by rapamycin.

(A) mTOR activity, as indicated by phosphorylation of S6, is increased in Ndufs4−/− mouse brain. Total IGF1R and S6 are decreased in Ndufs4−/− mice, suggesting feedback inhibition from chronic mTOR activation. Rapamycin potently inhibits phosphorylation of S6 and rescues levels of IGF1R and S6. (B) Total body fat progressively decreases in Ndufs4−/− mice but is maintained in rapamycin-treated mice. Fat mass differs by sex in control but not Ndufs4−/− mice (n = 4 to 6 mice per data point). (C and D) Liver fat droplets are deficient in vehicle-treated Ndufs4−/− mice and partially rescued by rapamycin (representative images, n > 6 stained per treatment; scale bar, ~100 µm) (C), as are free fatty acids detected by metabolomics (D) (n = 4 per treatment). (E) Accumulation of glycolytic intermediates in Ndufs4−/− brain is suppressed by rapamycin (n = 4 per treatment) (see fig. S14 and tables S1 to S3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, Student’s t test; error bars are ±SEM.

Taken together, our results demonstrate that inhibition of mTOR improves survival and health in the Ndufs4−/− model of Leigh syndrome. These findings raise the possibility that mTOR inhibitors may offer therapeutic benefit to patients with Leigh syndrome and potentially other mitochondrial disorders. Rapamycin derivatives have several adverse effects, however, including immunosuppression, hyperlipidemia, and decreased wound healing, which may limit their utility in this context, particularly in very young patients. Thus, a more detailed understanding of the mechanisms by which rapamycin alleviates disease in Ndufs4−/− mice should allow for the development of more targeted interventions to improve health in patients suffering from mitochondrial diseases for which there are no effective treatments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of Washington School of Medicine and Department of Pathology for funding to M.K. that allowed these studies to be performed. Supported by NIH training grant T32AG000057 (S.C.J., M.E.Y., and F.J.R.), NIH training grant T32ES007032 (B.M.W.), and an Amgen Scholar summer research scholarship (M.S.).

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials

www.sciencemag.org/content/342/6165/1524/suppl/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S14

Tables S1 to S3

References and Notes

- 1.Darin N, Oldfors A, Moslemi AR, Holme E, Tulinius M. Ann. Neurol. 2001;49:377–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Erven PM, et al. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 1987;89:217–230. doi: 10.1016/s0303-8467(87)80020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arii J, Tanabe Y. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1502–1509. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schleit J, et al. Aging Cell. 2013 10.1111/acel.12130. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quintana A, Kruse SE, Kapur RP, Sanz E, Palmiter RD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:10996–11001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006214107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breuer ME, Willems PH, Smeitink JA, Koopman WJ, Nooteboom M. IUBMB Life. 2013;65:202–208. doi: 10.1002/iub.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scacco S, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:17578–17582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001174200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruse SE, et al. Cell Metab. 2008;7:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramos FJ, et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4:144ra103. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison DE, et al. Nature. 2009;460:392–395. doi: 10.1038/nature08221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson SC, Rabinovitch PS, Kaeberlein M. Nature. 2013;493:338–345. doi: 10.1038/nature11861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor AL, Watson CJ, Bradley JA. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2005;56:23–46. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blagosklonny MV. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:683–688. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.4.10766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel KP, O’Brien TW, Subramony SH, Shuster J, Stacpoole PW. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012;106:385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.