Abstract

Many diagnostic and screening colonoscopies are performed on very elderly patients. Although colonoscopic yield increases with age, the potential benefits in such patients decrease because of shorter life expectancy and more frequent comorbidities. Colonoscopy in very elderly patients carries a greater risk of complications and morbidity than in younger patients, and is associated with lower completion rates and higher likelihood of poor bowel preparation. Thus, screening colonoscopy in very elderly patients should be performed only after careful consideration of potential benefits, risks and patient preferences. On the other hand, diagnostic and therapeutic colonoscopy are more likely to benefit even very elderly patients, and in most cases should be performed if indicated.

Keywords: Colonoscopy, Elderly, Colon polyp, Colon cancer, Screening, Surveillance, Complications, Yield, Bowel preparation

Core tip: Although colonoscopic yield increases with age, the potential benefits in elderly patients decrease because of shorter life expectancy and more frequent comorbidities. Colonoscopy in very elderly patients carries a greater risk of complications and morbidity than in younger patients. Thus, colonoscopy in elderly patients should be performed only after careful consideration of potential benefits, risks and patient preferences.

INTRODUCTION

Colonoscopy is currently the procedure of choice for whole colon evaluation in patients who present with lower gastrointestinal symptoms. In the United States, it is also the most effective and most commonly used modality for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in asymptomatic individuals (with or without a family history), and for surveillance in patients with a personal history of adenomatous polyps, CRC or inflammatory bowel disease. Finally, in appropriate circumstances it is an important therapeutic procedure, allowing for biopsy of suspicious lesions, treatment of bleeding sources, placement of stents, and, most of all, removal of colorectal adenomatous polyps, thereby preventing the potential occurrence of CRC[1].

COLONOSCOPY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS

Because the incidence of colorectal pathology and symptoms increase with age, a large proportion of diagnostic, screening and surveillance colonoscopies are performed on “elderly” (defined as those > 65 years of age) and “very elderly” patients (> 80 years). In North America, the number of screening procedures in elderly patients has increased dramatically ever since many insurance programs, including medicare, began to cover screening colonoscopy in average-risk beneficiaries[2,3]. However, performing colonoscopy in elderly patients poses a unique set of challenges. In the elderly, the risks and benefits of colonoscopy should be carefully assessed in light of lower life expectancy and the frequent presence of co-morbidities, so as to ensure that the potential benefits outweigh the risks and morbidity. This review will discuss issues pertaining to the procedural yield, potential benefits, technical feasibility, complication risks, logistical difficulties and costs associated with performing colonoscopy in elderly and very elderly individuals.

YIELD

The procedural yield is the percentage of patients who are found to have clinically significant findings (especially neoplasia) on colonoscopy. Generally, the yield of colonoscopy increases with age[4]. According to Surveillance Epidemiology End Results (SEER) registry data as of 2007, the incidence of CRC is 120 cases per 100000 in persons aged 50-64 years of age, 186 per 100000 in those 65-74, and 290.1 per 100000 in those ≥ 75[5]. It is well established that elderly patients have a higher prevalence of colorectal neoplasia[6,7], as well as other findings such as diverticulosis and hemorrhoids. As with younger patients, symptomatic elderly patients demonstrate a higher yield than those who are asymptomatic[8].

Numerous studies have confirmed high yields for both screening and diagnostic colonoscopy in elderly patients (Table 1). The reported yield of CRC in symptomatic elderly patients has ranged from 3.7% to 14.2%[9-12]. In a study on 200 symptomatic octogenarians, 80% had colonoscopic findings that explained their symptoms[13]. Controlled studies that compared the yield in patients of different ages have echoed these findings. In one study on 1353 elderly patients, the risk of CRC development was higher in patients > 80 compared to those 70-74 years old[6]. In another study that included 915 symptomatic and screening patients, more advanced adenomas and invasive cancers were identified in 53 patients over the age of 80 than in younger controls[14]. Studies on European patients as well as minority groups in the United States have also reported similar results. A large study on 2000 English patients showed that compared with younger patients, those > 65 years old had higher overall diagnostic yields (65% vs 45%) as well as CRC prevalence (7.1% vs 1.3%)[15], while another study on 1530 African American and Hispanic patients showed that the CRC yield was significantly higher in those over 65 years of age than in younger counterparts (7.8% vs 1.8%)[16].

Table 1.

Yield of colonoscopy in studies with subgroups of symptomatic and/or screening/surveillance “elderly” patients

| Ref. | n | Age (yr) | Completion | Cancers | Adenomas/polyps |

| Bat et al[10], 1992 | 436 | 80+ | 63% | 14% | 29.80% |

| Ure et al[48], 1995 | 354 | 70+ | 78% | 6% | 24% |

| Sardinha et al[49], 1999 | 403 | 80+ | 94% | 4.50% | - |

| Clarke et al[12], 2001 | 95 | 85+ | - | 12.70% | - |

| Lagares-Garcia et al[50], 2001 | 103 | 80+ | 92.70% | 11.60% | 19.40% |

| Arora et al[51], 2004 | 110 | 80+ | 97%1 | 20% | - |

| Syn et al[9], 2005 | 225 | 80+ | 56% | 11% | 25% |

| Yoong et al[52], 2005 | 316 | 85+ | 69% | 8.90% | 14.20% |

| Karajeh et al[15], 2006 | 1000 | 65+ | 81.80% | 7.10% | 6%2 |

Adjusted for non-traversable stricture;

Large polyps ≥ 1 cm in size.

COMPLICATIONS AND ADVERSE EVENTS

One of the main concerns with performing colonoscopy on elderly patients is the potential for increased risk of complications. Adverse events are typically categorized as those occurring during or immediately after the procedure and those with a delayed presentation. Cardiopulmonary complications are the most common peri-procedural adverse events. The level of sedation, presence of comorbidities and procedure length and complexity all contribute to the risk and should be addressed to the extent known during pre-procedural planning, especially for elective colonoscopies.

Although early, small studies suggested that colonoscopy in elderly patients did not result in more complications[17], more recent, larger and better designed studies have shown convincingly that colonoscopy in the elderly is associated with more risk than in younger patients. As demonstrated by a recent meta-analysis, very elderly patients had a significantly higher rate of overall adverse events, including gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation[18] (Table 2). Studies from Asia have also reported higher risks of cardiovascular complications despite the fact that elderly patients on average received lower doses of sedatives[19].

Table 2.

Complication risks based on data from meta-analysis by Day et al[18]

| Age group (yr) | > 65 | > 80 |

| Cumulative adverse events | 26.01 (25.0-27.0) | 34.91 (31.9-38.0) |

| Perforation | 1.0% (0.9-1.5) | 1.5% (1.1-1.9) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 6.3% (18.0-20.3) | 2.4% (1.1-4.6) |

| Cardiopulmonary complication | 19.1% (18.0-20.3) | 28.9% (26.2-31.8) |

| Mortality | 1.0% (0.7-2.2) | 0.5% (0.006-1.9) |

Per 1000 colonoscopies.

Nevertheless, when taken in context, the complication rate is still quite low even for patients over 85 years of age, and in most cases colonoscopy can be done safely with appropriate monitoring and precautions[20]. Furthermore, several studies have shown that propofol sedation, despite its propensity to lower blood pressure, can be used safely in elderly patients[21-23]. The overall major complication rate in patients over 80 is low, between 0.2% and 0.6%[11,15], although it increased with specific comorbid conditions[24]. A large retrospective study reported an overall perforation rate of 0.082% for adults undergoing colonoscopy, with advanced age as a significant predictor[25]. Studies in minority patients in the United States (African Americans and Hispanics)[16], as well as from Asia[26], have also reported that complication rates are low in elderly patients. When determining procedural risk, physiological age, i.e., presence of comorbidities, is more important than chronological age. Thus, the overall health status of the patient should be considered, instead of relying on rigid age cutoffs.

During colonoscopy, the vital signs, oxygen saturation and cardiac rhythm of all patients should be monitored continuously. Supplemental oxygen is often administered if patients are sedated. Increasingly, capnography is being used to identify early signs of respiratory depression. Conscious sedation is achieved by the use of a short-acting sedative with amnestic properties, such as intravenous midazolam or diazepam, and an opioid analgesic, such as fentanyl or meperidine. The use of deep sedation with propofol, typically administered by an anesthesia provider, is becoming more popular in the United States. However, gastroenterologist-administered propofol has also been shown to be safe in the elderly[22].

Up to one third of patients may have minor side-effects after outpatient colonoscopy, most frequently bloating or abdominal cramps. Depending on their level of independence, elderly patients living alone may require additional post-procedure care. Post-procedure calls within 48 h by medical staff may be helpful.

Many elderly patients have implanted cardiac pacemakers or defibrillators. The use of monopolar electrocautery during snare polypectomy can cause pacemaker inhibition or false detection of cardiac arrhythmias[27]. Thus, these devices are generally inactivated during the colonoscopy.

COLONOSCOPY COMPLETION RATES

Complete colonoscopy requires cecal intubation or, for those who have had an ileocecectomy, reaching the ileocolonic anastomosis. In the United States, studies on patients of all ages undergoing elective screening or surveillance colonoscopy report high completion rates above 95%[28]. Studies on symptomatic patients (including those with non-traversable obstructing lesions) report completion rates of around 83%[29].

Colonoscopy in the elderly is technically more challenging than in younger patients because of various factors, including more extensive diverticulosis, higher incidence of tortuosity or post-surgical adhesions, and higher risk of complications[4]. Elderly patients are also less likely to tolerate large amounts of sedation, and have a higher probability of suffering inadequate bowel preparation[13,30,31], both of which can preclude complete colonoscopy.

A wide range of completion rates in elderly patients have been reported, including 56% (this included 8 obstructing lesions that could not be traversed)[9], 63% (on the first attempt) or 89% (second attempt)[10], 83.5%[13], and as high as 88.1% (for patients > 73 years old)[30]. For patients in their late 60’s, the completion rate was quite respectable at 90.3% in one study[16], while a prospective study reported an “endoscopic success rate” of 90% for octogenarians[31]. Overall, a meta-analysis showed that for elderly patients > 65 years of age, the mean completion rate was 84%, while for those > 80, the completion rate was 84.7%[18]. Many of the studies that directly compared completion rates between elderly patients and younger controls showed a significant difference in favor of the younger group[16,31,32].

BOWEL PREPARATION ISSUES

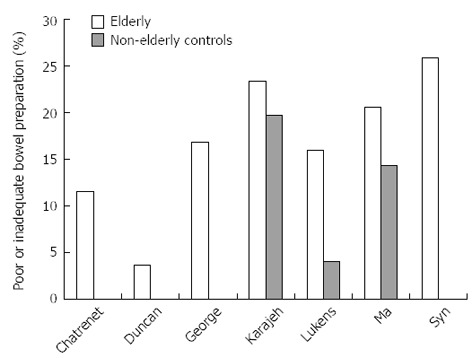

In a previous meta-analysis of 20 studies, suboptimal bowel preparation was documented in 18.8% of patients > 65 years of age, and in 12.1% of those > 80[18]. As summarized in Figure 1, elderly patients have a higher likelihood of poor bowel preparation due to slower colonic transit and higher incidence of obstipation[4,33]. Inadequate bowel preparation was a big factor in many studies that demonstrated lower colonoscopy completion rates in older patients[13,30,31]. The most commonly used bowel preparation regimen, 4 L of pegylated ethylene glycol, represents a substantial ingestion volume for elderly patients, who are also more likely to have renal, cardiac or hepatic conditions that make them ineligible for small volume alternative osmotic laxatives, such as sodium sulfate or sodium picosulfate. Moreover, frequent trips to the commode constitute a fall risk for the frail elderly patient with mobility issues.

Figure 1.

Published studies reporting rates of poor or inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy in elderly patients and non-elderly controls: Chatrenet[13], Duncan[11], George[53], Karajeh[15], Lukens[31], Ma[19] and Syn[9].

DECISION ANALYSES

Several decision analysis studies have addressed the costs, risks and benefits of colonoscopy in elderly patients. The potential for screening-related complications was greater than the estimated benefit in some population subgroups aged 70 years and older. At all ages and life expectancies, the potential reduction in mortality from screening outweighed the risk of colonoscopy-related death[34]. In another study, a patient with no familial risk factors with negative colonoscopy at age 50, 60 or 70 is less likely to benefit from additional screening colonoscopy compared to a 75 years old individual with no antecedent screening. Furthermore, an individual in superb health at age 80 may benefit from colonoscopy whereas a patient with prior low risk adenomas but moderate to severe health impairment is unlikely to benefit from colonoscopy even at age < 75. Upfront investment in screening and polypectomy in younger persons may decrease ultimate CRC-related costs, including subsequent screening and surveillance, for older Americans. While these savings could potentially be offset by future health costs for other diseases in the elderly, screening 50 years old persons would still be cost-effective[35].

EQUIPMENT AND LOGISTICAL ISSUES

Colonoscopes and accessories are the same for elderly patients as their younger counterparts, although some endoscopists favor pediatric colonoscopes because the more flexible shaft can facilitate passage in the presence of tortuosity or diverticulosis. All patients undergoing sedation need an adult escort after the procedure, potentially posing a burden on some elderly individuals living in social isolation.

OVERVIEW: SCREENING COLONOSCOPY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS

In the absence of additional risk factors such as family history, the prevailing consensus is to begin screening at age 50 and to continue at intervals determined by the screening modality used, as well as any history of adenomatous polyps or cancer. Currently, all three major United States gastroenterology societies (American Gastroenterological Association, American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and American College of Gastroenterology), the American Cancer Society and the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) have endorsed screening colonoscopy beginning at age 50 for average risk patients, with subsequent intervals of every 10 years in the absence of any personal history of adenomas or family history of CRC[36-39]. However, the USPSTF is the only body to recommend discontinuation of screening in average-risk individuals at age 75[39]. In a publication on colonoscopy developed by the American Gastroenterological Association for the American College of Physicians “Choosing Wisely” Campaign to control health care costs, it is stated that “routine (colonoscopies) usually aren’t needed after age 75.”

There is concern that continued screening in very elderly individuals is associated with diminishing utility and increasing costs, morbidity and risks to both individual and society. Life expectancy in light of advanced age and co-morbidities should be considered when considering screening in very elderly persons. Screening may not be warranted in asymptomatic patients for whom detecting and removing precancerous polyps would be unlikely to change their long term survival. Moreover, elderly patients who have been screened often incur frequent early repeat colonoscopies, leading to additional risk, morbidity and cost[40].

In a previous study using Declining Exponential Approximation of Life Expectancy analysis, we found that the prevalence of neoplasia was 13.8% in 50-54 years old patients, 26.5% in the 75 to 79 years old group, and 28.6% in the group aged 80 years or older. Despite higher prevalence of neoplasia in elderly patients, estimated mean extension in life expectancy was much lower in the group aged 80 years or older than in the 50 to 54 years old group (0.13 years vs 0.85 years). Even though prevalence of neoplasia increases with age, screening colonoscopy in very elderly persons (aged ≥ 80 years) results in only 15% of the expected gain in life expectancy in younger patients (Table 3)[41]. In a similar study, the survival of elderly patients undergoing colonoscopy was significantly lower than that for younger patients, with important screening implications[42]. Another decision analysis also showed that the benefits of screening were outweighed by screening-related complication risks in subgroups of patients over 75, especially if they were in poor health[34]. Surveys have shown that providers do incorporate age and comorbidity in screening recommendations; however, their recommendations were often inconsistent with guidelines[43]. Other factors come into play when screening decisions are made; for example, elderly patients of low socioeconomic class were less likely to be screened for CRC regardless of insurance status[44].

Table 3.

Outcomes for 1244 individuals who underwent screening colonoscopy; classification is according to the most advanced lesion for each patient[41]

| Age group (yr) | n | Patients with advanced neoplasia | Mean life-expectancy (yr) | Mean polyp lag time2 (yr) | Mean LE extension (yr) | Adjusted mean LE extension |

| 50-54 | 1034 | 331 (3.2%) | 28.87 | 5.23 | 0.85 | 2.94% |

| 75-79 | 147 | 7 (4.7%) | 10.37 | 5.44 | 0.17 | 1.64% |

| 80+ | 63 | 93 (14%) | 7.59 | 3.58 | 0.13 | 1.71% |

LE extension: Extension of life expectancy due to screening colonoscopy. Adjusted LE extension (%) = (LE extension/LE) × 100.

Includes one patient with high grade dysplasia and two patients with cancers;

These values are calculated only for patients with neoplastic findings, not the entire group;

Includes two patients with high-grade dysplastic polyps and one with cancer.

OVERVIEW: DIAGNOSTIC COLONOSCOPY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS

Many gastrointestinal conditions, such as constipation, incontinence, diverticulosis and hemorrhoids, are more common with advancing age. CRC is much more common in symptomatic patients over 65 than in younger controls, with a risk ratio as high as 17[45]. In all patients with colorectal symptoms, colonoscopy is usually the preferred diagnostic test for whole colon evaluation and has supplanted barium enemas and sigmoidoscopy. Direct visualization of the colonic mucosa can be extremely useful for the diagnosis of colitis and confirmation of polyps or masses. Of course, colonoscopy also allows for histologic assessment through biopsies. Certainly any elderly patient without prior colonoscopy who presents with significant new colorectal symptoms should be offered diagnostic colonoscopy.

One of the most common colorectal symptoms leading to hospitalization is lower gastrointestinal bleeding. With advancing age there is an increased incidence of bleeding from diverticulosis, arteriovenous malformations, malignancy, ischemic colitis, radiation colitis and ano-rectal lesions. When feasible, colonoscopy is the best diagnostic test and may offer therapeutic options. In elderly hospitalized patients, completing a 4 L polyethylene glycol preparation can be difficult; sometimes placement of a nasogastric tube is required. As an alternative diagnostic modality, the technetium red blood cell scan can localize active bleeding, while angiography is another diagnostic option, and like colonoscopy offers therapeutic possibilities.

OVERVIEW: THERAPEUTIC COLONOSCOPY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS

Colonoscopy offers a variety of therapeutic options to control bleeding, remove polyps and small tumors, and relieve colonic obstruction due to benign or malignant strictures; these maneuvers are especially useful in elderly patients because they may obviate the need for surgery. However, small polyps may not need to be removed because the relative complication risk is high and the benefit is probably low[41].

For bleeding patients, endoscopic hemostasis can be achieved using epinephrine injection, thermal or electrocoagulation, or deployment of clips. Polypectomy is performed in the same manner independent of age, i.e., small polyps are removed with cold snare polypectomy or biopsy forceps, larger polyps are removed with snare polypectomy with monopolar coagulation, and flat or sessile polyps are removed after saline submucosal injection, perhaps supplemented by argon plasma coagulation. With increasing age, large and flat polyps are more common. Benign colonic strictures may be seen in patients with a surgical anastomosis, or in the presence of chronic ischemic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease or diverticulitis. In such patients, endoscopic dilation can be attempted under fluoroscopic observation. Malignant strictures are at greater risk of perforation with dilation. In selected patients with colonic malignancy who are not surgical candidates or who need preoperative decompression, self-expanding stents can be placed across the obstruction. Studies on endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection have included small numbers of elderly and very elderly patients, showing that these procedures are possible even in advanced age, although there are significant complication risks similar to those seen in younger patients[46,47].

CONCLUSION

Colonoscopy in very elderly patients (over 80 years of age) carries a greater risk of complications, adverse events and morbidity than in younger patients, and is associated with lower completion rates and higher chance of poor bowel preparation. Although colonoscopic yield increases with age, several studies have suggested that the potential benefits are significantly decreased because of shorter life expectancy and greater prevalence of comorbidities. Thus, screening colonoscopy in very elderly patients should be performed only after careful consideration of potential benefits, risks and patient preferences. Diagnostic and therapeutic colonoscopy are more likely to benefit even very elderly patients, and in most cases should be performed if indicated.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Albuquerque A, Agaba EA, Uraoka T S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Hankey BF, Shi W, Bond JH, Schapiro M, Panish JF, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harewood GC, Lieberman DA. Colonoscopy practice patterns since introduction of medicare coverage for average-risk screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:72–77. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(03)00294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh H, Demers AA, Xue L, Turner D, Bernstein CN. Time trends in colon cancer incidence and distribution and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy utilization in Manitoba. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1249–1256. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loffeld RJ, Liberov B, Dekkers PE. Yearly diagnostic yield of colonoscopy in patients age 80 years or older, with a special interest in colorectal cancer. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2012;12:298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Day LW, Walter LC, Velayos F. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in the elderly patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1197–1206; quiz 1207. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harewood GC, Lawlor GO, Larson MV. Incident rates of colonic neoplasia in older patients: when should we stop screening? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1021–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, Ries LA, Wu X, Jamison PM, Wingo PA, Howe HL, Anderson RN, Edwards BK. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101:3–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smoot DT, Collins J, Dunlap S, Ali-Ibrahim A, Nouraie M, Lee EL, Ashktorab H. Outcome of colonoscopy in elderly African-American patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2484–2487. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0965-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Syn WK, Tandon U, Ahmed MM. Colonoscopy in the very elderly is safe and worthwhile. Age Ageing. 2005;34:510–513. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bat L, Pines A, Shemesh E, Levo Y, Zeeli D, Scapa E, Rosenblum Y. Colonoscopy in patients aged 80 years or older and its contribution to the evaluation of rectal bleeding. Postgrad Med J. 1992;68:355–358. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.68.799.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncan JE, Sweeney WB, Trudel JL, Madoff RD, Mellgren AF. Colonoscopy in the elderly: low risk, low yield in asymptomatic patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:646–651. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0306-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke GA, Jacobson BC, Hammett RJ, Carr-Locke DL. The indications, utilization and safety of gastrointestinal endoscopy in an extremely elderly patient cohort. Endoscopy. 2001;33:580–584. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-15313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chatrenet P, Friocourt P, Ramain JP, Cherrier M, Maillard JB. Colonoscopy in the elderly: a study of 200 cases. Eur J Med. 1993;2:411–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens T, Burke CA. Colonoscopy screening in the elderly: when to stop? Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1881–1885. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karajeh MA, Sanders DS, Hurlstone DP. Colonoscopy in elderly people is a safe procedure with a high diagnostic yield: a prospective comparative study of 2000 patients. Endoscopy. 2006;38:226–230. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-921209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akhtar AJ, Padda MS. Safety and efficacy of colonoscopy in the elderly: experience in an innercity community hospital serving African American and Hispanic patients. Ethn Dis. 2011;21:412–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiPrima RE, Barkin JS, Blinder M, Goldberg RI, Phillips RS. Age as a risk factor in colonoscopy: fact versus fiction. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:123–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Day LW, Kwon A, Inadomi JM, Walter LC, Somsouk M. Adverse events in older patients undergoing colonoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:885–896. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma WT, Mahadeva S, Kunanayagam S, Poi PJ, Goh KL. Colonoscopy in elderly Asians: a prospective evaluation in routine clinical practice. J Dig Dis. 2007;8:77–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-9573.2007.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zerey M, Paton BL, Khan PD, Lincourt AE, Kercher KW, Greene FL, Heniford BT. Colonoscopy in the very elderly: a review of 157 cases. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1806–1809. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martínez JF, Aparicio JR, Compañy L, Ruiz F, Gómez-Escolar L, Mozas I, Casellas JA. Safety of continuous propofol sedation for endoscopic procedures in elderly patients. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2011;103:76–82. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082011000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heuss LT, Schnieper P, Drewe J, Pflimlin E, Beglinger C. Conscious sedation with propofol in elderly patients: a prospective evaluation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1493–1501. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schilling D, Rosenbaum A, Schweizer S, Richter H, Rumstadt B. Sedation with propofol for interventional endoscopy by trained nurses in high-risk octogenarians: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Endoscopy. 2009;41:295–298. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1119671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Mariotto AB, Meekins A, Topor M, Brown ML, Ransohoff DF. Adverse events after outpatient colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:849–57, W152. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-12-200906160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arora G, Mannalithara A, Singh G, Gerson LB, Triadafilopoulos G. Risk of perforation from a colonoscopy in adults: a large population-based study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:654–664. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsutsumi S, Fukushima H, Osaki K, Kuwano H. Feasibility of colonoscopy in patients 80 years of age and older. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:1959–1961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niehaus M, Tebbenjohanns J. Electromagnetic interference in patients with implanted pacemakers or cardioverter-defibrillators. Heart. 2001;86:246–248. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.3.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson DB, McQuaid KR, Bond JH, Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Johnston TK. Procedural success and complications of large-scale screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:307–314. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.121883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loffeld RJ, van der Putten AB. The completion rate of colonoscopy in normal daily practice: factors associated with failure. Digestion. 2009;80:267–270. doi: 10.1159/000236030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cardin F, Andreotti A, Martella B, Terranova C, Militello C. Current practice in colonoscopy in the elderly. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2012;24:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lukens FJ, Loeb DS, Machicao VI, Achem SR, Picco MF. Colonoscopy in octogenarians: a prospective outpatient study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1722–1725. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Houissa F, Kchir H, Bouzaidi S, Salem M, Debbeche R, Trabelsi S, Moussa A, Said Y, Najjar T. Colonoscopy in elderly: feasibility, tolerance and indications: about 901 cases. Tunis Med. 2011;89:848–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jafri SM, Monkemuller K, Lukens FJ. Endoscopy in the elderly: a review of the efficacy and safety of colonoscopy, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:161–166. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181c64d64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ko CW, Sonnenberg A. Comparing risks and benefits of colorectal cancer screening in elderly patients. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1163–1170. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ladabaum U, Phillips KA. Colorectal cancer screening differential costs for younger versus older Americans. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Bond J, Dash C, Giardiello FM, Glick S, Johnson D, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570–1595. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, Schoenfeld PS, Burke CA, Inadomi JM. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected] Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:739–750. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davila RE, Rajan E, Baron TH, Adler DG, Egan JV, Faigel DO, Gan SI, Hirota WK, Leighton JA, Lichtenstein D, et al. ASGE guideline: colorectal cancer screening and surveillance. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:546–557. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:627–637. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richards RJ, Crystal S. The frequency of early repeat tests after colonoscopy in elderly medicare recipients. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:421–431. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0736-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin OS, Kozarek RA, Schembre DB, Ayub K, Gluck M, Drennan F, Soon MS, Rabeneck L. Screening colonoscopy in very elderly patients: prevalence of neoplasia and estimated impact on life expectancy. JAMA. 2006;295:2357–2365. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.20.2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kahi CJ, Azzouz F, Juliar BE, Imperiale TF. Survival of elderly persons undergoing colonoscopy: implications for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:544–550. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kahi CJ, van Ryn M, Juliar B, Stuart JS, Imperiale TF. Provider recommendations for colorectal cancer screening in elderly veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1263–1268. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1110-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koroukian SM, Xu F, Dor A, Cooper GS. Colorectal cancer screening in the elderly population: disparities by dual Medicare-Medicaid enrollment status. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:2136–2154. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00585.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeCosse JJ, Tsioulias GJ, Jacobson JS. Colorectal cancer: detection, treatment, and rehabilitation. CA Cancer J Clin. 1994;44:27–42. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.44.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee EJ, Lee JB, Lee SH, Kim do S, Lee DH, Lee DS, Youk EG. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors--1,000 colorectal ESD cases: one specialized institute’s experiences. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:31–39. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2403-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buchner AM, Guarner-Argente C, Ginsberg GG. Outcomes of EMR of defiant colorectal lesions directed to an endoscopy referral center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ure T, Dehghan K, Vernava AM, Longo WE, Andrus CA, Daniel GL. Colonoscopy in the elderly. Low risk, high yield. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:505–508. doi: 10.1007/BF00206836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sardinha TC, Nogueras JJ, Ehrenpreis ED, Zeitman D, Estevez V, Weiss EG, Wexner SD. Colonoscopy in octogenarians: a review of 428 cases. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1999;14:172–176. doi: 10.1007/s003840050205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lagares-Garcia JA, Kurek S, Collier B, Diaz F, Schilli R, Richey J, Moore RA. Colonoscopy in octogenarians and older patients. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:262–265. doi: 10.1007/s004640000339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arora A, Singh P. Colonoscopy in patients 80 years of age and older is safe, with high success rate and diagnostic yield. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:408–413. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01715-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoong KK, Heymann T. Colonoscopy in the very old: why bother? Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:196–197. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.023374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.George ML, Tutton MG, Jadhav VV, Abulafi AM, Swift RI. Colonoscopy in older patients: a safe and sound practice. Age Ageing. 2002;31:80–81. doi: 10.1093/ageing/31.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]