Abstract

This article focuses on the incidence, predictors, classification, impact on prognosis, and management of bleeding associated with the treatment of acute coronary syndrome. The issue of bleeding complications is related to the continual improvement of ischemic heart disease treatment, which involves mainly (a) the widespread use of coronary angiography, (b) developments in percutaneous coronary interventions, and (c) the introduction of new antithrombotics. Bleeding has become an important health and economic problem and has an incidence of 2.0% to 17%. Bleeding significantly influences both the short- and long-term prognoses. If a group of patients at higher risk of bleeding complications can be identified according to known risk factors and a risk scoring system can be developed, we may focus more on preventive measures that should help us to reduce the incidence of bleeding.

Introduction

Selective coronary angiography as a diagnostic method followed by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) as a therapeutic method has become routine practice for patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) as well as for patients with stable forms of ischemic heart disease. As a result of the more widespread application of selective coronary angiography and PCI in general practice, a greater number of older people and patients with serious comorbidities are receiving this procedure. Owing to the development of new techniques for cardiac catheterization and the continual production of new generations of highly effective antiplatelet drugs, the care of patients with ACS has improved, resulting in reductions in rates of death due to ischemic events as well as periprocedural ischemic complications, ischemic stroke, and heart failure [1,2]. All of these actions lead to an increased risk of bleeding complications in these patients which is significantly associated with worse short-term and long-term prognoses [3]. As a result of these findings, bleeding complications, which have been disregarded for quite some time, have become a highly significant medical and economic problem. If it is expected that more attention will be focused on this issue in the future, this attention should concurrently lead to a special effort of creating one standard bleeding complication classification which is necessary for unambiguous comparison of outcomes from clinical trials evaluating treatment strategies in ACS.

Incidence and predictors of bleeding complications

The incidence of bleeding complications in trials with patients with ACS varies, ranging from 2.0% to 17.6% [3-8]. These varying results come from trials examining different demographic data, access sites, cardiac catheterization techniques, and pharmacotherapy regimes and from randomized studies in which specific defined groups of patients are included and which do not reflect the real-world clinical experience. Several factors associated with an increased risk of periprocedural bleeding have been identified. These factors are age, gender, body weight, renal insufficiency, and the techniques used in invasive procedures [9]. Older age is a strong independent risk factor for major bleeding during hospitalization, and this risk factor increases by approximately 30% per decade of age [10]. Additionally, women and patients with renal insufficiency were found to exhibit a higher risk of hemorrhage and the risk rate is also associated with the use of invasive techniques and the sheath size [11]. Because these risk factors have been identified, the scale for predicting the risk for the development of major bleeding complications in patients with ACS has been evaluated on the basis of results from the ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage strategy) and the HORIZONS-AMI (Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction) trials. This simple integer-based scoring system calculates individual risk scores by using six independent measurements of factors that have been identified to be associated with an increased risk of bleeding complications (gender, age, serum creatinine, white blood cell count, anemia, and presentation), combined with the type of anticoagulation therapy applied (heparin + inhibitors of GP IIb/IIIa versus bivalirudin monotherapy). Four categories of bleeding are then defined according to the total integer score: low (<10), moderate (10 to 14), high (15 to 19), and very high (>20) [12]. It is hoped that this simple scoring system for identifying patients at increased risk of bleeding can be used as a tool for individualization of the treatment strategy for each patient, similar to an easily applied scale for predicting the risk of bleeding versus thrombotic events which has begun to be used in general practice in patients with atrial fibrillation, leading to a recommendation of optimal therapy: HAS-BLED (Hypertension, Abnormal renal/liver function, Stroke, Bleeding history or predisposition, Labile International Normalized Ratio, Elderly, Drugs/alcohol concomitantly) score and CHA2DS2-VASc (Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age of at least 75 years, Diabetes mellitus, Stroke, Vascular disease, Age of 65 to 74 years, Sex category) score [13].

New antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy

Simultaneously with the development of the technique of coronary artery stenting, great advances have been made in relation to the arsenal of antithrombotic agents reducing ischemic events. A substantial proportion of patients (especially when the average age of patients undergoing PCI increases) is indicated concurrently for chronic anticoagulant and dual antiplatelet therapy. In all of these cases, the question about safety of these new agents and their combination arises.

In a group of thienopyridines, which typically are added to acetylsalicylate acid, clopidogrel is considered the gold standard and is widely used in general practice and as a reference drug in trials examining new antiplatelet drugs. Newly introduced P2Y12 antagonists, prasugrel and ticagrelor, promise to be more effective in reducing ischemic events in patients with ACS [14]. So far, the most important trials in which both of these drugs were separately compared with clopidogrel have been the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial (prasugrel versus clopidogrel) [15] and the PLATO trial (ticagrelol versus clopidogrel) [16]. Significant reductions were found in the total number of ischemic events in both trials comparing new antiplatelet drugs with clopidogrel [17,18]. When focused on the safety of these drugs, TRITON showed a significantly increased number of bleeding complications for patients receiving prasugrel [15]. For ticagrelor in the PLATO trial, the total rate of major bleeding was similar in the two groups - PLATO major bleeding (11.6% versus 11.2%, P = 0.43), TIMI major bleeding (7.9% versus 7.7%, P = 0.56), and GUSTO (Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries) severe bleeding (2.9% versus 3.1%, P = 0.22) - as were procedure-related bleeding rate and incidence of fatal bleeding. At 30-day follow-up, there was an increased number of major non-coronary artery bypass graft-related bleeding in the ticagrelor group. There were no differences in major bleeding rates between ticagrelor and clopidogrel in a group of patients presumed to be at higher risk of bleeding (age of at least 75 years, weight of less than 60 kg, chronic kidney disease, aspirin dose of greater than 325 mg on the day of randomization, pre-randomization clopidogrel administration, or clopidogrel loading dose) [16]. Nevertheless, the benefit of both of these new drugs seems to exceed the consequential risk, and according to the new European Society of Cardiology guidelines, they should preferably be used in all patients with ACS (with clearly defined contraindications) [19,20]. Of course, additional randomized trials clarifying an optimal dose and focusing mainly on the high-risk group of patients are needed, and head-to-head trials directly comparing both of these agents are necessary.

It is even more complicated when it comes to the problem of concomitant antiplatelet and oral anticoagulant (OAC) therapy. The risk of bleeding for those who use triple therapy (OAC + aspirin + clopidogrel) is significantly higher [21,22]. Therefore, it is very difficult to find an optimal balance between benefit and safety in any combinations of drugs affecting hemostasis. According to current guidelines, triple therapy is recommended for all patients indicated for anticoagulant therapy and concurrently receiving intracoronary stent, with different recommended lengths of this triple-therapy period (according to ACS presented and type of stent used), followed by a period of combined therapy of OAC and a single antiplatelet drug [13]. However, all of these recommendations come from a consensus of experts on the basis of a limited amount of evidence [23]. A new perspective on this topic may result from the recently published multicenter randomized WOEST (What is the Optimal antiplatElet and anticoagulant therapy in patients with oral anticoagulation and coronary StenTing) trial, which compared triple therapy (OAC + aspirin + clopidogrel) and dual therapy (OAC + clopidogrel). The results of this trial showed no difference in the number of ischemic events but did show a significantly reduced number of bleeding complications in a group of patients receiving dual therapy (OAC + clopidogrel) [24]. These results may lead to new recommendations in the near future.

In the era of new antiplatelet drugs, new anticoagulants have also been introduced in the last decade. Novel oral anticoagulants, direct thrombin inhibitors (for example, dabigatran), and oral direct factor Xa inhibitors (for example, rivaroxaban and apixaban) have been tested in several clinical trials (RELY, ROCKET-AF, AVERROES, and ARISTOTLE) [25-28], and data from these trials did not show worse results in the incidence of ischemic events compared with warfarin and in some cases showed even better safety [13]. These results are promising for further general use of new oral anticoagulants, but more data and experience are still necessary. Data for the use of new anticoagulants in triple therapy (thus in combination with dual antiplatelet therapy) are still insufficient.

Technique of cardiac catheterization

Since cardiac catheterization started to be performed in practice in the early 1980s, great developments have been made in terms of equipment and techniques. Initially, the size of the catheter sheath used was 12F, whereas sizes of 5F or even smaller are currently employed. The size of the catheter is known to be one of the risk factors for bleeding complications [29,30]. At the beginning of the cardiac catheterization era, all procedures were performed via a femoral approach (puncture of the femoral artery). However, owing to the reduction in sheath size in the last decade and the minimization of other tools and instruments, a radial approach now can be used and slowly is becoming a routine technique practiced world-wide [31-33]. Several trials have compared the advantages and disadvantages of the two approaches, mostly in the form of retrospective trials. A radial approach is usually more comfortable for patients and appears to be safer and to reduce bleeding complications. A meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled studies comparing the association of different types of complications with the use of these two puncture sites showed that there are no differences in the rates of death and severe bleeding complications and that there is a significantly lower incidence of local minor bleeding complications associated with radial access [34]. The lack of relevant independent data led to the need for a large randomized trial. Between 2006 and 2010, RIVAL (Radial versus Femoral access for coronary intervention), a randomized, parallel, multicenter trial, was carried out. The results showed that the rate of primary outcomes (the composite of death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and non-coronary artery bypass graft-related major bleeding at 30 days) did not differ between patients in the radial access group and those in the femoral access group (3.7% in the radial access group compared with 4.0% in the femoral access group), but there was an increased number of cases of access-site bleeding in the femoral access group (42 of 3,507 patients in the radial group compared with 106 of 3,514 in the femoral group exhibited a large hematoma; hazard ratio (HR) 0.40, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.57, P < 0.0001). When the primary outcomes associated with a subgroup of procedures performed at highly experienced radial access centers were compared, a significant benefit was detected for patients in the radial access group. In summary, this study showed that both femoral and radial access appear to be safe and effective, and an improvement was observed when the radial approach was used in association with bleeding complications related to the access site. Furthermore, it showed that specific technical skills and a more experienced team can lead to greater benefits from radial access [35].

Classification of bleeding complications

The first formal approach for classifying the severity of bleeding as a complication related to treatment with antithrombotic drugs in patients with ACS was developed during the Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) trial in 1988 [36]. The TIMI classification was based mainly on laboratory criteria. TIMI major bleeding was defined as bleeding associated with a decrease in hemoglobin of greater than 50.0 g/L (or 15% in hematocrit) or intracranial bleeding. TIMI minor bleeding was defined as any bleeding (for example, hematuria, hematemesis, melena, retroperitoneal bleeding, or hematoma) with a hemoglobin loss of greater than 30 g/L (or at least 10% in hematocrit). Criteria for major bleeding were extended to hemorrhagic death and cardiac tamponade [37]. This classification, sometimes modified, has been widely applied in many trials despite its limitations resulting from the preference of laboratory values over clinical outcomes. However, the second widespread classification scheme for bleeding complications established in the GUSTO trial in 1993 relies mainly on clinical data [38]. GUSTO investigators determined severe bleeding to be intracranial bleeding or any bleeding that compromises hemodynamic state and that requires treatment. Moderate bleeding is defined as any bleeding that does not lead to hemodynamic compromise but that requires transfusion. Mild bleeding does not need any specific treatment. The TIMI and GUSTO classifications have been subsequently applied in a wide range of trials, but owing to their limitations (the use of pure laboratory versus pure clinical data), they are applied mostly in combination with variable modifications or with only selected elements of these classifications. A slightly modified GUSTO scale was used in the ASSENT-3 [39], HERO-2 [40], and PARAGON-A [41] and PARAGON-B [42] trials, and combinations of the TIMI and GUSTO classifications were applied in the SYNERGY [43] and PURSUIT [44] trials. Many other studies (CURE, ACUITY, OASIS-5, REPLACE-2, OASIS-6, HORIZONS-AMI, CURRENT-OASIS-7, PLATO, and GRACE [16,45-52]) established their own classifications for evaluating hemorrhagic complications (Table 1). Some of these classifications aim toward using an increased number of reported details, whereas others prefer simplicity (GRACE). They also show large differences on the basis of suspicious events and outcomes.

Table 1.

| Trial | Year | Classification used | Fatal/life-threatening | Major | Minor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIMI | 1988 | Intracranial or associated with an HGB decrease of greater than 5 g/dL (or 15% in hematocrit) | HGB decreasing greater than 3 g/dL (or hematocrit decreasing at least 10%) | ||

| TIMI II | 1997 | Intracranial hemorrhage, pericardial hemorrhage with tamponade, and greater than 5 g/dL drop in HGB |

Blood loss greater than 3 g/dL but less than 5 g/dL or if the patient had gross hematurie, hemoptysis, or hematemesis | ||

| GUSTO | 1993 | Intracerebral or if it resulted in substantial hemodynamic compromise requiring treatment | Need for transfusion | Other bleeding, not requiring transfusion or causing hemodynamic compromise | |

| SYNERGY | 2004 | TIMI + GUSTO | |||

| PARAGON-A | 1998 | Modified GUSTO | Intracranial hemorrhage or bleeding leading to hemodynamic compromise requiring intervention | Bleeding requiring transfusion, an HGB decrease of at least 5 g/dL, or a hematocrit decrease of at least 15% | |

| PARAGON-B | 2002 | ||||

| PURSUIT | 1998 | GUSTO | |||

| CURE | 2004 | Fatal, that led to a decrease in HGB concentration of greater than 5 g/dL, that caused significant hypotension requiring intravenous inotropes or surgical intervention, or that resulted in symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage or necessitated transfusion of at least 4 units of blood | Bleeding that required at least 2 units blood or was significantly disabling or intraocular | ||

| ACUITY | 2004 | Intracranial bleeding, intraocular bleeding, access-site hemorrhage requiring intervention, hematoma of at least 5 cm in diameter, reduction in HGB concentration of at least 4 g/dL without an overt source of bleeding, reduction in HGB concentration of at least 3 g/dL with an overt source of bleeding, reoperation for bleeding, use of any blood product transfusion | |||

| OASIS-5 | 2005 | Clinically overt bleeding that is fatal, symptomatic intracranial, retroperitoneal, or intraocular, an HGB decrease of at least 3.0 g/dL (with each blood transfusion unit counting for 1.0 g/dL of HGB), or requiring transfusion of at least 2 units of red blood cells | |||

| REPLACE-2 | 2006 | Any HGB drop of greater than 4 g/dL, overt bleeding with HGB drop of greater than 3 g/dL, a blood transfusion of at least 2 units or retroperitoneal, intraocular, or intracranial hemorrhage | Overt bleeding not meeting criteria for major bleeding | ||

| OASIS-6 | 2006 | Fatal, intracranial, cardiac tamponade, or bleeding that was felt to be clinically significant and resulted in an HGB decrease of greater than 5 g/dL, with each transfused unit counted as a 1.0 g/dL drop in HGB | Clinically overt bleeding associated with an HGB decrease of 3.0 to 5.0 g/dL (with each transfused unit counted as a 1.0 g/dL drop in HGB) and which did not meet the criteria for severe hemorrhage |

||

| HORIZONS-AMI | 2008 | Intracranial bleeding, intraocular bleeding, retroperitoneal bleeding, access-site hemorrhage requiring surgery or a radiologic or interventional procedure, hematoma of at least 5 cm in diameter at the puncture site, reduction in HGB concentration of at least 4 g/dL without an overt source of bleeding, reduction in HGB concentration of at least 3 g/dL with an overt source of bleeding, reoperation for bleeding, or use of any blood product transfusion | |||

| ACUITY | 2010 | Fatal or leading to an HGB drop of at least 5 g/dL, or significant hypotension with the need for inotropes, or requiring surgery (other than vascular site repair), or symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, or requiring transfusion of at least 4 units of red blood cells or equivalent in whole blood | Significantly disabling, intraocular bleeding leading to significant loss of vision or bleeding requiring transfusion of 2 or 3 units of red blood cells or equivalent in whole blood | ||

| PLATO | 2011 | Fatal bleeding, intrapericardial bleeding with cardiac tamponade, intracranial bleeding, severe hypotension, hypovolemic shock due to bleeding, HGB decline of 5.0 g/dL, need for transfusion of more than 4 units | Clinical significant disability, HGB drop of 3 to 5 g/dL, requiring transfusion of 2 to 3 units of red blood cells | Any bleeding event requiring medical intervention but not meeting the criteria for major bleeding | |

| GRACE | 2003 | Life-threatening bleeding requiring transfusion of at least 2 units of packed red blood cells, or resulting in an absolute decrease in hematocrit of at least 10% or death, or hemorrhagic/subdural hematoma | |||

| RIVAL | 2011 | Non-CABG related major bleeding that (a) is fatal, (b) results in transfusion of at least 2 units of red blood cells or equivalent whole blood, (c) causes significant hypotension with the need for inotropes or surgical intervention (a requirement for surgical access-site repair will constitute major bleeding only if there has been significant hypotension or transfusion of at least 2 units), (d) causes significantly disabling sequellae, or (e) is intracranial and symptomatic or intraocular and leads to significant visual loss | Bleeding events that did not meet the criteria for a major bleed and required transfusion of more than one unit of blood or modification of the drug regiment |

ACUITY, Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CURE, Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; GUSTO, Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Arteries; HGB, hemoglobin; HORIZONS-AMI, Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction; OASIS, Organization to Assess Strategies for Ischemic Syndrome; PARAGON, Platelet IIb/IIIa Antagonism for the Reduction of Acute Coronary Syndrome Events in a Global Organization Network; PLATO, Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes; PURSUIT, Platelet Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa in Unstable Angina: Receptor Suppression Using Integrilin Therapy; REPLACE, Randomized Evaluation in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Linking Angiomax to Reduced Clinical Events II; RIVAL, Radial vs Femoral Access for Coronary Intervention; SYNERGY, Superior Yield of the New Strategy of Enoxaparin, Revascularization and Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibitors; TIMI, Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction.

According to the different definitions employed, it is very difficult for clinicians and experts to come to accurate conclusions regarding the outcomes from different trials and, thus, to evaluate the safety of new techniques and antitrombotic drugs. When data from two randomized studies were compared and analyzed to determine the association between TIMI and GUSTO bleeding and 30-day and 6-month death/myocardial infarction, a stepwise increase was observed in the adjusted hazard of 30-day death/myocardial infarction using GUSTO and TIMI classifications separately. However, in a model including both definitions, the risk of GUSTO bleeding persisted whereas TIMI bleeding did not [53]. In light of these findings, it is more than clear that one unified classification for bleeding complications is necessary in the future.

Efforts to standardize the classification of bleeding complications

In light of variability in the data and the difficulty of interpreting general outcomes from the available studies, there is a tendency toward standardizing the definition of bleeding. However, it is difficult to do so because of demographic differences and the varying outcomes expected. Classification evaluating in-hospital mortality in patients with ACS requiring rescue PCI would be focused more on severe and life-threatening complications. On the other hand, classification for subsequent follow-up should cover wider range of bleeding complications (including superficial bleeding as petechia and easy bruising). This classification must be practical, easy to implement, and meaningful for clinical outcomes and have appropriate sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, and consistency across health-care systems [54]. One of the first attempts to create a new classification for bleeding events was introduced in 2007 and was termed the BloodScore classification, which is based on point scores for each type of bleeding complication [55]. As defined, this classification covers a wide spectrum of bleeding events (from nuisance bleeding to severe, life-threatening complications) and can be easily applied and compared in trials. On the other hand, it does not reflect any effect on the hemodynamic impact or need for treatment, and this may represent a limitation for general use.

In light of the need for a new general classification for bleeding complications, a group of experts convened in April 2008 and developed a new strategy for assessing the severity of bleeding associated with ACS by using existing data from previous trials. The Academic Bleeding Consensus (ABC) Multidisciplinary Working Group, a group of clinical researchers and representatives from the health-care and pharmaceutical industries, established a consensus statement that recommended evaluating specific data in each trial and divided the evaluated data into three categories (each assigned a different color): essential (red), recommended (orange), and optional (green) (Table 2). The collection and reporting data rely mainly on clinical and laboratory elements, the time and site of bleeding, the direct consequences of bleeding, and the outcomes after hemorrhage. Advantages of this method include the independent collection of all relevant data associated with bleeding complications, not influenced by the primary endpoint of each trial; the potential to compare clinical trials post hoc; and the fact that it can be used to construct a new standard bleeding definition [56]. To decrease the differences between prior definitions of bleeding, this complicated evaluation is most likely necessary, but its complexity and the associated inconvenience for users could be limitations to its wide application in clinical practice.

Table 2.

Academic Bleeding Consensus standards for the collection and reporting of bleeding complications [56]

| Assigned color | Recommended data collection |

|---|---|

| Red (essential for all studies) | Clinical bleeding events Date/time of diagnosis Location - gastrointestinal, genitourinary, intracranial, vascular access site, other Related to a procedure, yes/no |

| Laboratory parameters (dates and times of values should be recorded) Most recent hemoglobin value before bleed is recognized Lowest hemoglobin value within 24 hours after onset of bleeding has been recognized Change in hemoglobin associated with clinical bleeding event |

|

| Consequences of bleeding Death related to bleeding (yes/no) Blood transfusion--type, number of units, associated with overt bleeding (yes/no), hemoglobin value at the time of transfusion, dates and times of administration Resulted in permanent disability (yes/no) |

|

| Orange (recommended for all studies) | Bleeding resulted in discontinuation of therapy (yes/no) |

| Bleeding prompted dose alteration of therapy (yes/no) | |

| Green (optional for all studies) | Bleeding resulted in hemodynamic compromise (yes/no) |

| Bleeding resulted in transient disability (yes/no) | |

| Bleeding resulted in increased length of stay (yes/no) Number of hospital days added Number of intensive care unit days added |

|

| Hemoglobin decrease associated with procedures |

The attempt to develop a standardized classification for bleeding complications in patients undergoing invasive procedures continued. In 2011, the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC), a group of independent experts, summarized all of the available evidence and data from clinical trials and evaluated new standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials. Five main types of bleeding were defined, scaled from 0 to 5, beginning with type 0, corresponding to no evidence of bleeding, and ending with type 5, indicating fatal bleeding (Table 3). Several categories include subgroups specifying each type of bleeding. Bleeding associated with surgical revascularization appears to be crucial to include but was not included in previous bleeding classifications but may have a great influence on outcomes in many clinical trials. This classification was constructed to capture bleeding events that are important and meaningful for patients and clinical outcomes but to remain simple, broadly applicable, and easy to use. These characteristics make this recent classification promising for use in routine clinical practice. The authors note that it is necessary to verify the accuracy and usefulness of this new classification in clinical trials and therefore appeal to all researchers to report bleeding events according to the BARC definition [57].

Table 3.

Definition of bleeding used by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium [57]

| Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Type 0 | No bleeding |

| Type 1 | Bleeding that is not actionable and does not cause the patient to seek unscheduled performance of studies, hospitalization, or treatment by a health-care professional |

| Type 2 | Any overt, actionable sign of hemorrhage (for example, more bleeding than would be expected for a clinical circumstance, including bleeding found by imaging alone) that does not fit the criteria for type 3, 4, or 5 but does meet at least one of the following criteria: (1) requiring non-surgical, medical intervention by a health-care professional, (2) leading to hospitalization or increased level of care, and (3) prompting evaluation |

| Type 3 | |

| Type 3a | Overt bleeding plus hemoglobin drop of 3 to 5 g/dLa (provided that hemoglobin drop is related to bleed) Any transfusion with overt bleeding |

| Type 3b | Overt bleeding plus hemoglobin drop at least 5 g/dLa (provided that hemoglobin drop is related to bleed) Cardiac tamponade Bleeding requiring surgical intervention for control (excluding dental/nasal/skin/hemorrhoid) Bleeding requiring intravenous vasoactive drugs |

| Type 3c | Intracranial hemorrhage (does not include microbleeds or hemorrhagic transformation; does include intraspinal) Subcategories; confirmed by autopsy or imaging or lumbar puncture Intra-ocular bleed compromising vision |

| Type 4: CABG-related bleeding | Perioperative intracranial bleeding within 48 hours Reoperation following closure of sternotomy for the purpose of controlling bleeding Transfusion of at least 5 units of whole blood or packed red blood cells within a 48-hour periodb Chest tube output of at least 2 L within a 24-hour period If a CABG-related bleed is not adjudicated as at least a type 3 severity event, it will be classified as 'not a bleeding event' |

| Type 5: fatal bleeding | |

| Type 5a | Probable fatal bleeding: no autopsy or imaging confirmation, but clinically suspicious |

| Type 5b | Definite fatal bleeding: overt bleeding or autopsy or imaging confirmation |

Platelet transfusions should be recorded and reported but are not included in these definitions until further information is obtained about the relationship to outcomes. aCorrected for transfusion (1 unit of packed red blood cells or 1 unit of whole blood = 1 g/dL hemoglobin). bOnly allogeneic transfusions are considered transfusions for Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 4 bleeding. Cell saver products will not be counted. CABG, coronary artery bypass graft.

Bleeding and prognosis

Despite the variation in incidence across studies, a strong association with a worse short-term as well as long-term prognosis was found for patients exhibiting bleeding complications [3,58-60]. In 2006, the data from a group of 34,146 ACS patients enrolled in the OASIS Registry, OASIS-2, and CURE studies were analyzed to examine the association between bleeding and death or ischemic events. Patients with bleeding complications presented a 5-fold higher incidence of death during the first 30 days and a 1.5-fold higher incidence of death between 30 days and 6 months after an invasive procedure. An association was found between the severity of bleeding and an increased risk of death [3]. Also, the type of bleeding, in the context of location (access and non-access bleeding), may significantly affect the prognosis. The data analysis from the REPLACE-2, ACUITY, and HORIZONS-AMI trials found increased total 1-year mortality for patients presenting bleeding complications, but the risk was significantly higher when manifested as non-access bleeding compared with access-site bleeding (HR 2.27, 95% CI 1.42 to 3.64, P < 0.0007) [61].

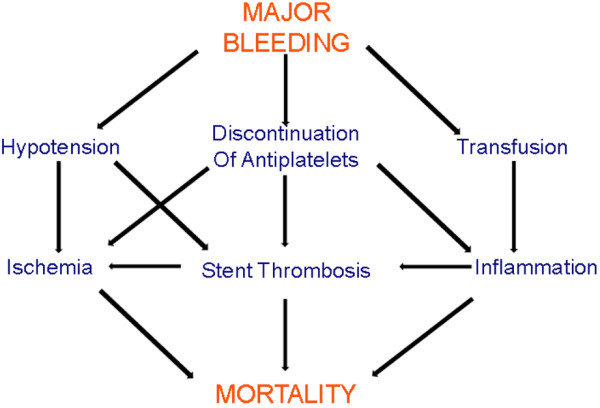

The reason for the worse outcomes in patients exhibiting bleeding was not completely explained. It is assumed that bleeding leads to hemodynamic compromise, decreasing tissue oxygenation (for example, because of anemia or hypotension) and consequently activating adaptive mechanisms, which may trigger a chain of other adverse complications [62] (Figure 1). Antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs are often interrupted or at least reduced with an increased risk of subsequent ischemic events. Finally, blood transfusion administration is assumed to have protrombotic effects and therefore influence the higher mortality rate [63].

Figure 1.

Bleeding and prognosis of patients with acute coronary syndrome.

Management

The management of bleeding complications ideally should be focused mainly on preventive measures, especially in high-risk patients. For each patient, the therapy should be personally tailored according to the bleeding risk score. These recommendations demonstrate the importance of an individual approach to each of the many steps associated with the treatment of patients with ACS, particularly patients with stable forms of ischemic heart disease [64]. Firstly, the real benefit versus the risk from an invasive procedure should be considered thoroughly. For risk score assessment, the scoring method described in the 'Incidence and predictors of bleeding complications' section may be used [12]. In regard to the invasive procedure itself, a radial approach and a smaller sheath size are assumed to be associated with a lower risk of bleeding complication and therefore should be preferred, when available, for patients with a higher risk of bleeding [29]. The same decrease in the rate of bleeding complications may be achieved with the use of specific closure devices. There are several types of vascular closure devices. The most often used active closure devices (for example, Angio-Seal (St Jude Medical, Minnetonka, Minnesota) or Perclose A-T (Abbott Vascular, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA)) were part of the several studies comparing standard manual compression with these devices [65]. These studies showed decrease in incidence of access-site bleeding when special vascular closure devices were used (similar to decrease achieved using radial access) [66,67]. Independent randomized trials are necessary, but these devices should be thoroughly considered for patients exhibiting a higher risk of bleeding [68]. To avoid gastrointestinal bleeding, proton pump inhibitors should be used for patients with a history of gastrointestinal bleeding, especially when dual antiplatelet therapy is necessary, and rehydratation therapy needs to be emphasized for patients with renal insufficiency. The administration of a specific drug and its dosage for anticoagulant and antitrombotic therapy are other important criteria that require a highly individual perspective [69]. According to evidence-based medical data from large randomized trials (SYNERGY, OASIS-, ACUITY, and HORIZONS-AMI), the guidelines of the American College of Chest Physicians noted that there is a decrease in the risk of bleeding complications when using unfractionated heparin rather than low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction receiving fibrinolytic therapy, whereas in patients with non-ST-elevation ACS and unstable angina pectoris, fondaparinux appears to be safer than LMWH, and bivalirudin (a direct thrombin inhibitor) is associated with a lower bleeding risk than GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors in combination with heparin [70]. In the era of new antitrombotic drugs, data from large randomized trials and the guidelines arising from them should provide clues for treatment, and the optimal therapy should be considered according to individual risk stratification [19,20,71].

Once bleeding complications have occurred, the specific treatment is always determined on the basis of a combination of several factors: (a) the severity of bleeding, associated with hemodynamic compromise of the patient; (b) the possibility of applying specific, local treatment; and (c) the need for anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy versus the risk of discontinuous treatment. Local minor bleeding usually does not require any specific treatment, and manual compression may be sufficient, without a need for a change in the established therapy. For more severe bleeding, the applied treatment will be individually determined while the patient is closely monitored. If the patient is hemodynamically unstable, antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy should preferably be interrupted until the bleeding is under control and its administration is safe again, despite the higher risk of ischemic events [62,72]. In the context of blood transfusion, the administration should be considered carefully [73]. According to recent guidelines for ACS, blood transfusion is recommended only in case of compromised hemodynamical status or hematocrit of less than 25% or hemoglobin level of less than 7 g/dL [19].

Conclusions

As percutaneous diagnostic coronary angiography and coronary intervention have become widespread and more effective therapeutically and with the development of new antiplatelet drugs, it may be stated that we have almost reached the boundary regarding the reduction of ischemic events as complications of these methods. Now is the time to focus on and improve the safety of these procedures. The reduction of bleeding complications associated with invasive procedures in cardiology, which is of both short- and long-term prognostic value, should be the next step and should become a point of interest for all clinical physicians as well as for researchers.

Abbreviations

ACS: acute coronary syndrome; ACUITY: Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy; ARISTOTLE: Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation; ASSENT-3: Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic-3; AVERROES: Apixaban versus acetylsalicylic acid to prevent stroke in atrial fibrillation patients who have failed or are unsuitable for vitamin K antagonist treatment; BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CI: confidence interval; CURE: Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events; CURRENT OASIS-7: Clopidogrel Optimal Loading Dose Usage to Reduce Recurrent Events/Optimal Antiplatelet Strategy for Interventions; GPI: glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor; GRACE: Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; GUSTO: Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Arteries; HERO-2: Hirulog and Early Reperfusion or Occlusion-2; HORIZONS-AMI: Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction; HR: hazard ratio; LMWH: low-molecular-weight heparin; NOAC: novel oral anticoagulant; OAC: oral anticoagulant; OASIS: Organization to Assess Strategies for Ischemic Syndrome; PARAGON: Platelet IIb/IIIa Antagonism for the Reduction of Acute Coronary Syndrome Events in a Global Organization Network; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; PLATO: Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes; PURSUIT: Platelet Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa in Unstable Angina: Receptor Suppression Using Integrilin Therapy; RELY: Randomised Evaluation of Long term anticoagulant therapY; REPLACE: Randomized Evaluation in percutaneous coronary intervention Linking Angiomax to Reduced Clinical Events II; RIVAL: RadIal Vs femorAL access for coronary intervention; ROCKET-AF: Rivaroxaban Once daily oral direct factor Xa inhibition Compared with vitamin K antagonism for prevention of stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation; SYNERGY: Superior Yield of the New Strategy of Enoxaparin: Revascularization and Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibitors; TIMI: Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction; TRITON: TRial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet InhibitioN with Prasugrel.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Magdalena Doktorova, Email: magdalena.doktorova@fnkv.cz.

Zuzana Motovska, Email: motovska.zuzana@gmail.com.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by The Charles University Prague, Research Project PRVOUK P35 and Third Faculty of Medicine, Charles University Prague, Research Project UNCE204010.

References

- Fox KA, Steg PG, Eagle KA, Goodman SG, Anderson FA Jr, Granger CB, Flather MD, Budaj A, Quill A, Gore JM. Decline in rates of death and heart failure in acute coronary syndromes, 1999-2006. JAMA. 2007;17:1892–1900. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.17.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;17:71–86. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eikelboom JW, Mehta SR, Anand SS, Xie C, Fox KA, Yusuf S. Adverse impact of bleeding on prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2006;17:774–782. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.612812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox KA, Carruthers K, Steg PG, Avezum A, Granger CB, Montalescot G, Goodman SG, Gore JM, Quill AL, Eagle KA. Has the frequency of bleeding changed over time for patients presenting with an acute coronary syndrome? The global registry of acute coronary events. Eur Heart J. 2010;17:667–675. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer MA, Karweit JA, Cascade EF, Lin ND, Topol EJ. Practice patterns and outcomes of percutaneous coronary interventions in the United States: 1995 to 1997. Am J Cardiol. 2002;17:924–929. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(02)02240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnaird TD, Stabile E, Mintz GS, Lee CW, Canos DA, Gevorkian N, Pinnow EE, Kent KM, Pichard AD, Satler LF, Weissman NJ, Lindsay J, Fuchs S. Incidence, predictors, and prognostic implications of bleeding and blood transfusion following percutaneous coronary interventions. Am J Cardiol. 2003;17:930–935. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00972-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs S, Kornowski R, Teplitsky I, Brosh D, Lev E, Vaknin-Assa H, Ben-Dor I, Iakobishvili Z, Rechavia E, Battler A, Assali A. Major bleeding complicating contemporary primary percutaneous coronary interventions-incidence, predictors, and prognostic implications. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2009;17:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta SK, Frutkin AD, Lindsey JB, House JA, Spertus JA, Rao SV, Ou FS, Roe MT, Peterson ED, Marso SP. Bleeding in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the development of a clinical risk algorithm from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;17:222–229. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.108.846741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KP, Chen AY, Roe MT, Newby LK, Gibson CM, Allen-LaPointe NM, Pollack C, Gibler WB, Ohman EM, Peterson ED. Excess dosing of antiplatelet and antithrombin agents in the treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2005;17:3108–3116. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.24.3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor WB, Anstrom KJ, Muhlbaier LH, Grosswald R, Weintraub WS, O'Neill WW, Peterson ED. Contemporary outcome trends in the elderly undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions: results in 7,472 octogenarians. National Cardiovascular Network Collaboration. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;17:723–730. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00777-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscucci M, Fox KA, Cannon CP, Klein W, Lopez-Sendon J, Montalescot G, White K, Goldberg RJ. Predictors of major bleeding in acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Eur Heart J. 2003;17:1815–1823. doi: 10.1016/S0195-668X(03)00485-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehran R, Pocock SJ, Nikolsky E, Clayton T, Dangas GD, Kirtane AJ, Parise H, Fahy M, Manoukian SV, Feit F, Ohman ME, Witzenbichler B, Guagliumi G, Lansky AJ, Stone GW. A risk score to predict bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;17:2556–2566. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, Savelieva I, Atar D, Hohnloser SH, Hindricks G, Kirchhof P, Bax JJ, Baumgartner H, Ceconi C, Dean V, Deaton C, Fagard R, Funck-Brentano C, Hasdai D, Hoes A, Knuuti J, Kolh P, McDonagh T, Moulin C, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Vahanian A, Windecker S, Vardas P. et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J. 2012;17:2719–2747. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WE, Wang H, Wang X, Zeng C. A transition of P2Y antagonists for acute coronary syndrome: benefits, risks and costs. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2013. in press . [DOI] [PubMed]

- Antman EM, Wiviott SD, Murphy SA, Voitk J, Hasin Y, Widimsky P, Chandna H, Macias W, McCabe CH, Braunwald E. Early and late benefits of prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a TRITON-TIMI 38 (TRial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet InhibitioN with Prasugrel-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction) analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;17:2028–2033. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker RC, Bassand JP, Budaj A, Wojdyla DM, James SK, Cornel JH, French J, Held C, Horrow J, Husted S, Lopez-Sendon J, Lassila R, Mahaffey KW, Storey RF, Harrington RA, Wallentin L. Bleeding complications with the P2Y12 receptor antagonists clopidogrel and ticagrelor in the PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Eur Heart J. 2011;17:2933–2944. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SA, Antman EM, Wiviott SD, Weerakkody G, Morocutti G, Huber K, Lopez-Sendon J, McCabe CH, Braunwald E. Reduction in recurrent cardiovascular events with prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes from the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial. Eur Heart J. 2008;17:2473–2479. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli P, Wallentin L, Reyes E, Horrow J, Husted S, Angiolillo DJ, Ardissino D, Maurer G, Morais J, Nicolau JC, Oto A, Storey RF, James SK, Cannon CP. Reduction in first and recurrent cardiovascular events with ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel in the PLATO Study. Circulation. 2013;17:673–680. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.124248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, Bax J, Boersma E, Bueno H, Caso P, Dudek D, Gielen S, Huber K, Ohman M, Petrie MC, Sonntag F, Uva MS, Storey RF, Wijns W, Zahger D. ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2011;17:2999–3054. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, Badano LP, Blömstrom-Lundqvist C, Borger MA, Di Mario C, Dickstein K, Ducrocq G, Fernandez-Aviles F, Gershlick AH, Giannuzzi P, Halvorsen S, Huber K, Juni P, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Lenzen MJ, Mahaffey KW, Valgimigli M, van 't Hof A, Widimsky P, Zahger D. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;17:2569–2619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurram Z, Chou E, Minutello R, Bergman G, Parikh M, Naidu S, Wong SC, Hong MK. Combination therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel and warfarin following coronary stenting is associated with a significant risk of bleeding. J Invasive Cardiol. 2006;17:162–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeEugenio D, Kolman L, DeCaro M, Andrel J, Chervoneva I, Duong P, Lam L, McGowan C, Lee G, Ruggiero N, Singhal S, Greenspon A. Risk of major bleeding with concomitant dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients receiving long-term warfarin therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;17:691–696. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.5.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lip GY, Huber K, Andreotti F, Arnesen H, Airaksinen JK, Cuisset T, Kirchhof P, Marín F. Consensus Document of European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis. Antithrombotic management of atrial fibrillation patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and/or undergoing coronary stenting: executive summary - a Consensus Document of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis, endorsed by the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) Eur Heart J. 2010;17:1311–1318. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewilde WJ, Oirbans T, Verheugt FW, Kelder JC, De Smet BJ, Herrman JP, Adriaenssens T, Vrolix M, Heestermans AA, Vis MM, Tijsen JG, van 't Hof AW, ten Berg JM. WOEST study investigators. Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;17:1107–1115. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, Pogue J, Reilly PA, Themeles E, Varrone J, Wang S, Alings M, Xavier D, Zhu J, Diaz R, Lewis BS, Darius H, Diener HC, Joyner CD, Wallentin L. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;17:1139–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, Breithardt G, Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Piccini JP, Becker RC, Nessel CC, Paolini JF, Berkowitz SD, Fox KA, Califf RM. ROCKET AF Investigators. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;17:883–891. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly SJ, Eikelboom J, Joyner C, Diener HC, Hart R, Golitsyn S, Flaker G, Avezum A, Hohnloser SH, Diaz R, Talajic M, Zhu J, Pais P, Budaj A, Parkhomenko A, Jansky P, Commerford P, Tan RS, Sim KH, Lewis BS, Van Mieghem W, Lip GY, Kim JH, Lanas-Zanetti F, Gonzalez-Hermosillo A, Dans AL, Munawar M, O'Donnell M, Lawrence J, Lewis G, Afzal R, Yusuf S. Apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;17:806–817. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, Al-Khalidi HR, Ansell J, Atar D, Avezum A, Bahit MC, Diaz R, Easton JD, Ezekowitz JA, Flaker G, Garcia D, Geraldes M, Gersh BJ, Golitsyn S, Goto S, Hermosillo AG, Hohnloser SH, Horowitz J, Mohan P, Jansky P, Lewis BS, Lopez-Sendon JL, Pais P, Parkhomenko A, Verheugt FW, Zhu J, Wallentin L. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;17:981–992. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor WJ, Mahaffey KW, Huang Z, Das P, Gulba DC, Glezer S, Gallo R, Ducas J, Cohen M, Antman EM, Langer A, Kleiman NS, White HD, Chisholm RJ, Harrington RA, Ferguson JJ, Califf RM, Goodman SG. Bleeding complications in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing early invasive management can be reduced with radial access, smaller sheath sizes, and timely sheath removal. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;17:73–83. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchler JR, Ribeiro EE, Falcao JL, Martinez EE, Buchler RD, Feres F, Maielo JR, Haddad N, Ramires JF, Ellis SG. A randomized trial of 5 versus 7 French guiding catheters for transfemoral percutaneous coronary stent implantation. J Interv Cardiol. 2008;17:50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2007.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SV, Ou FS, Wang TY, Roe MT, Brindis R, Rumsfeld JS, Peterson ED. Trends in the prevalence and outcomes of radial and femoral approaches to percutaneous coronary intervention: a report from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;17:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan S, Rao SV. Radial versus femoral access for percutaneous coronary intervention: implications for vascular complications and bleeding. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2012;17:502–509. doi: 10.1007/s11886-012-0287-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand OF, Larose E, Rodes-Cabau J, Gleeton O, Taillon I, Roy L, Poirier P, Costerousse O, Larochelliere RD. Incidence, predictors, and clinical impact of bleeding after transradial coronary stenting and maximal antiplatelet therapy. Am Heart J. 2009;17:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyal D, Bertrand OF, Rinfret S, Shimony A, Eisenberg MJ. Meta-analysis of ten trials on the effectiveness of the radial versus the femoral approach in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2012;17:813–818. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly SS, Yusuf S, Cairns J, Niemela K, Xavier D, Widimsky P, Budaj A, Niemela M, Valentin V, Lewis BS, Avezum A, Steg PG, Rao SV, Gao P, Afzal R, Joyner CD, Chrolavicius S, Mehta SR. Radial versus femoral access for coronary angiography and intervention in patients with acute coronary syndromes (RIVAL): a randomised, parallel group, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2011;17:1409–1420. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao AK, Pratt C, Berke A, Jaffe A, Ockene I, Schreiber TL, Bell WR, Knatterud G, Robertson TL, Terrin ML. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Trial - phase I: hemorrhagic manifestations and changes in plasma fibrinogen and the fibrinolytic system in patients treated with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator and streptokinase. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;17:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passamani E, Hodges M, Herman M, Grose R, Chaitman B, Rogers W, Forman S, Terrin M, Knatterud G, Robertson T. et al. The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) phase II pilot study: tissue plasminogen activator followed by percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;17(5 Suppl B):51B–64B. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(87)80429-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An international randomized trial comparing four thrombolytic strategies for acute myocardial infarction. The GUSTO investigators. N Engl J Med. 1993;17:673–682. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309023291001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic Regimen (ASSENT)-3 Investigators. Efficacy and safety of tenecteplase in combination with enoxaparin, abciximab, or unfractionated heparin: the ASSENT-3 randomised trial in acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 2001;17:605–613. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05775-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HD, Ellis CJ, French JK, Aylward P. Hirudin (desirudin) and Hirulog (bivalirudin) in acute ischaemic syndromes and the rationale for the Hirulog/Early Reperfusion Occlusion (HERO-2) Study. Aust N Z J Med. 1998;17:551–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1998.tb02109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International, randomized, controlled trial of lamifiban (a platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor), heparin, or both in unstable angina. The PARAGON Investigators. Platelet IIb/IIIa Antagonism for the Reduction of Acute coronary syndrome events in a Global Organization Network. Circulation. 1998;17:2386–2395. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.24.2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moliterno DJ. Patient-specific dosing of IIb/IIIa antagonists during acute coronary syndromes: rationale and design of the PARAGON B study. The PARAGON B International Steering Committee. Am Heart J. 2000;17:563–566. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(00)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson JJ, Califf RM, Antman EM, Cohen M, Grines CL, Goodman S, Kereiakes DJ, Langer A, Mahaffey KW, Nessel CC, Armstrong PW, Avezum A, Aylward P, Becker RC, Biasucci L, Borzak S, Col J, Frey MJ, Fry E, Gulba DC, Guneri S, Gurfinkel E, Harrington R, Hochman JS, Kleiman NS, Leon MB, Lopez-Sendon JL, Pepine CJ, Ruzyllo W, Steinhubl SR, Teirstein PS, Toro-Figueroa L, White H. Enoxaparin vs unfractionated heparin in high-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes managed with an intended early invasive strategy: primary results of the SYNERGY randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;17:45–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa with eptifibatide in patients with acute coronary syndromes. The PURSUIT Trial Investigators Platelet Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa in Unstable Angina: Receptor Suppression Using Integrilin Therapy N Engl J Med 199817436–443.9705684 [Google Scholar]

- Mehta SR, Yusuf S. The Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) trial programme; rationale, design and baseline characteristics including a meta-analysis of the effects of thienopyridines in vascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2000;17:2033–2041. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone GW, Bertrand M, Colombo A, Dangas G, Farkouh ME, Feit F, Lansky AJ, Lincoff AM, Mehran R, Moses JW, Ohman M, White HD. Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage strategY (ACUITY) trial: study design and rationale. Am Heart J. 2004;17:764–775. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta SR, Granger CB, Eikelboom JW, Bassand JP, Wallentin L, Faxon DP, Peters RJ, Budaj A, Afzal R, Chrolavicius S, Fox KA, Yusuf S. Efficacy and safety of fondaparinux versus enoxaparin in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: results from the OASIS-5 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;17:1742–1751. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal V, Lincoff AM, Cohen DJ, Gurm HS, Hu T, Desmet WJ, Kleiman NS, Bittl JA, Feit F, Topol EJ. Outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes who are treated with bivalirudin during percutaneous coronary intervention: an analysis from the Randomized Evaluation in PCI Linking Angiomax to Reduced Clinical Events (REPLACE-2) trial. Am Heart J. 2006;17:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Afzal R, Pogue J, Granger CB, Budaj A, Peters RJ, Bassand JP, Wallentin L, Joyner C, Fox KA. Effects of fondaparinux on mortality and reinfarction in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the OASIS-6 randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;17:1519–1530. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.joc60038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehran R, Brodie B, Cox DA, Grines CL, Rutherford B, Bhatt DL, Dangas G, Feit F, Ohman EM, Parise H, Fahy M, Lansky AJ, Stone GW. The Harmonizing Outcomes with RevasculariZatiON and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction (HORIZONS-AMI) Trial: study design and rationale. Am Heart J. 2008;17:44–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta SR, Bassand JP, Chrolavicius S, Diaz R, Fox KA, Granger CB, Jolly S, Rupprecht HJ, Widimsky P, Yusuf S. Design and rationale of CURRENT-OASIS 7: a randomized, 2 × 2 factorial trial evaluating optimal dosing strategies for clopidogrel and aspirin in patients with ST and non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes managed with an early invasive strategy. Am Heart J. 2008;17:1080–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.07.026. e1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiles MK, Dabbous OH, Fox KA. Bleeding events with antithrombotic therapy in patients with unstable angina or non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; insights from a large clinical practice registry (GRACE) Heart Lung Circ. 2008;17:5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2007.02.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SV, O'Grady K, Pieper KS, Granger CB, Newby LK, Mahaffey KW, Moliterno DJ, Lincoff AM, Armstrong PW, Van de Werf F, Califf RM, Harrington RA. A comparison of the clinical impact of bleeding measured by two different classifications among patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;17:809–816. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhubl SR, Kastrati A, Berger PB. Variation in the definitions of bleeding in clinical trials of patients with acute coronary syndromes and undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions and its impact on the apparent safety of antithrombotic drugs. Am Heart J. 2007;17:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serebruany VL, Atar D. Assessment of bleeding events in clinical trials - proposal of a new classification. Am J Cardiol. 2007;17:288–290. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.07.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SV, Eikelboom J, Steg PG, Lincoff AM, Weintraub WS, Bassand JP, Rao AK, Gibson CM, Petersen JL, Mehran R, Manoukian SV, Charnigo R, Lee KL, Moscucci M, Harrington RA. Standardized reporting of bleeding complications for clinical investigations in acute coronary syndromes: a proposal from the academic bleeding consensus (ABC) multidisciplinary working group. Am Heart J. 2009;17:881–886. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.10.008. e881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, Gibson CM, Caixeta A, Eikelboom J, Kaul S, Wiviott SD, Menon V, Nikolsky E, Serebruany V, Valgimigli M, Vranckx P, Taggart D, Sabik JF, Cutlip DE, Krucoff MW, Ohman EM, Steg PG, White H. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;17:2736–2747. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle BJ, Rihal CS, Gastineau DA, Holmes DR Jr. Bleeding, blood transfusion, and increased mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention: implications for contemporary practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;17:2019–2027. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle BJ, Ting HH, Bell MR, Lennon RJ, Mathew V, Singh M, Holmes DR, Rihal CS. Major femoral bleeding complications after percutaneous coronary intervention: incidence, predictors, and impact on long-term survival among 17,901 patients treated at the Mayo Clinic from 1994 to 2005. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;17:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segev A, Strauss BH, Tan M, Constance C, Langer A, Goodman SG. Predictors and 1-year outcome of major bleeding in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: insights from the Canadian Acute Coronary Syndrome Registries. Am Heart J. 2005;17:690–694. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheugt FW, Steinhubl SR, Hamon M, Darius H, Steg PG, Valgimigli M, Marso SP, Rao SV, Gershlick AH, Lincoff AM, Mehran R, Stone GW. Incidence, prognostic impact, and influence of antithrombotic therapy on access and nonaccess site bleeding in percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;17:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steg PG, Huber K, Andreotti F, Arnesen H, Atar D, Badimon L, Bassand JP, De Caterina R, Eikelboom JA, Gulba D, Hamon M, Helft G, Fox KA, Kristensen SD, Rao SV, Verheugt FW, Widimsky P, Zeymer U, Collet JP. Bleeding in acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous coronary interventions: position paper by the Working Group on Thrombosis of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2011;17:1854–1864. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shishehbor MH, Madhwal S, Rajagopal V, Hsu A, Kelly P, Gurm HS, Kapadia SR, Lauer MS, Topol EJ. Impact of blood transfusion on short- and long-term mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;17:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauerman HL, Rao SV, Resnic FS, Applegate RJ. Bleeding avoidance strategies. Consensus and controversy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;17:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz BG, Burstein S, Economides C, Kloner RA, Shavelle DM, Mayeda GS. Review of vascular closure devices. J Invasive Cardiol. 2010;17:599–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marso SP, Amin AP, House JA, Kennedy KF, Spertus JA, Rao SV, Cohen DJ, Messenger JC, Rumsfeld JS. Association between use of bleeding avoidance strategies and risk of periprocedural bleeding among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2010;17:2156–2164. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora N, Matheny ME, Sepke C, Resnic FS. A propensity analysis of the risk of vascular complications after cardiac catheterization procedures with the use of vascular closure devices. Am Heart J. 2007;17:606–611. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavris DR, Wang Y, Jacobs S, Gallauresi B, Curtis J, Messenger J, Resnic FS, Fitzgerald S. Bleeding and vascular complications at the femoral access site following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI): an evaluation of hemostasis strategies. J Invasive Cardiol. 2012;17:328–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SV. Strategies to reduce bleeding among patients with ischemic heart disease treated with antiplatelet therapies. Am J Cardiol. 2009;17(5 Suppl):60C–63C. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman S, Beyth RJ, Kearon C, Levine MN. Hemorrhagic complications of anticoagulant and thrombolytic treatment: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition) Chest. 2008;17(6 Suppl):257S–298S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K, Garcia MA, Ardissino D, Buszman P, Camici PG, Crea F, Daly C, De Backer G, Hjemdahl P, Lopez-Sendon J, Marco J, Morais J, Pepper J, Sechtem U, Simoons M, Thygesen K, Priori SG, Blanc JJ, Budaj A, Camm J, Dean V, Deckers J, Dickstein K, Lekakis J, McGregor K, Metra M, Osterspey A, Tamargo J, Zamorano JL. Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris: executive summary: The Task Force on the Management of Stable Angina Pectoris of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2006;17:1341–1381. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannucci PM, Franchini M. Mechanism of hemostasis defects and management of bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Eur J Intern Med. 2010;17:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SV, Jollis JG, Harrington RA, Granger CB, Newby LK, Armstrong PW, Moliterno DJ, Lindblad L, Pieper K, Topol EJ, Stamler JS, Califf RM. Relationship of blood transfusion and clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2004;17:1555–1562. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.13.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]