Abstract

While T1DM has been traditionally seen as a minor concern in the larger picture of pediatric ailments, new data reveals that the incidence of T1DM has assumed alarming proportions. It has long been clear that while the disease may be diagnosed at an early age, its impact is not isolated to afflicted children. The direct impact of the disease on the patient is debilitating due to the nature of the disease and lack of proper access to treatment in India. But this impact is further compounded by the utter apathy and often times antipathy, which patients withT1DM have to face. Lack of awareness of the issue in all stakeholders, low access to quality healthcare, patient, physician, and system level barriers to the delivery of optimal diabetes care are some of the factors which hinder successful management of T1DM. The first international consensus meet on diabetes in children was convened with the aim of providing a common platform to all the stakeholders in the management of T1DM, to discuss the academic, administrative and healthcare system related issues. The ultimate aim was to articulate the problems faced by children with diabetes in a way that centralized their position and focused on creating modalities of management sensitive to their needs and aspirations. It was conceptualized to raise a strong voice of advocacy for improving the management of T1DM and ensuring that “No child should die of diabetes”. The unique clinical presentations of T1DM coupled with ignorance on the part of the medical community and society in general results in outcomes that are far worse than that seen with T2DM. So there is a need to substantially improve training of HCPs at all levels on this neglected aspect of healthcare.

Keywords: Awareness creation, guidelines on insulin use, patient centric approach, role of policy makers and Government, Type 1 Diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, T1DM accounts for approximately 78,000 children, with 70,000 new cases diagnosed each year.[1] These individuals have an absolute deficiency of insulin secretion, primarily due to T-cell mediated pancreatic islet beta cell destruction, making them prone to ketoacidosis.[2] The number of children developing this form of diabetes is increasing rapidly every year, especially, amongst the youngest age groups.[1] While there are geographic differences in trends, the overall annual increase in the incidence of T1DM among children (especially < 15 years) is estimated at around 3% worldwide. Increased incidence can be explained by an increased detection rate and autoimmunity among children.[1] However, unlike west, increasing trends in T1DM with a nonautoimmunological etiology might be responsible for increased incidence in India; of the cases diagnosed with T1DM, 23% did not show much correlation with autoimmunity in physician-reported clinical experience, showing high levels of C-peptide (>0.8%) and presence of glutamate decarboxylase and IL-2 antibodies. Many factors such as environmental pollution, toxins in food, chemical-intensive cultivation practices, sanitation, stress factors, and viral infections have been implicated in the increased incidence of T1DM in children, apart from conventional risk factors such as history of T2DM and genetic predisposition.

INCIDENCE AND PREVALENCE IN INDIA

Globally, around 78,000 children under the age of 15 years are estimated to develop T1DM. Of the estimated 4,90,000 children living with the disorder, 24% come from the European Region and 23% from the South-east Asian Region, according the IDF 2011.[1] Although studies on the incidence of T1DM in India are scarce (with documented statistics available only from three studies), it is estimated that there are over 1,00,000 cases of T1DM in India with a 3-5% increase annually.[1] A study conducted in Karnal showed that the overall prevalence of T1DM is 10.20/1,00,000 population. The prevalence was higher in urban populations (26.6/1,00,000) and in men (11.56/1,00,000) as compared to rural areas (4.27/1,00,000) and women (8.6/1,00,000).[3] Two other previous studies, conducted in Chennai and Karnataka, showed the overall prevalence to be 10.5 and 3.8 cases per 100,000 population, respectively.[4,5] Currently data collection for the ICMR-led “Diabetes in Young” registry for T1DM is under progress at more than 70 centers across the country and efforts are underway to begin these registries in all the states. From the data currently available, around 6,600 cases of T1DM have been identified and center-wise variations in the prevalence were found, in certain cases. Though the incidence of T1DM in the population is low when compared to the west, the burden of diabetes is high in India due to a large population.[6]

Surprisingly, the prevalence of T2DM in children also showed a rising trend. Increasing sedentary lifestyle seen in all sections of the population, including people with diabetes, further amplify the incidence rate.[7] Irrespective of the socioeconomic status, this disease is equally prevalent among all sections of the society. It is a well-known fact that socioeconomic factors and poverty are the most important barriers impeding access to quality healthcare in India.[8] Thus, it is highly likely that a majority of the children with T1DM who belong to the poorer sections of the society, show far worse outcomes in India than in developed nations.

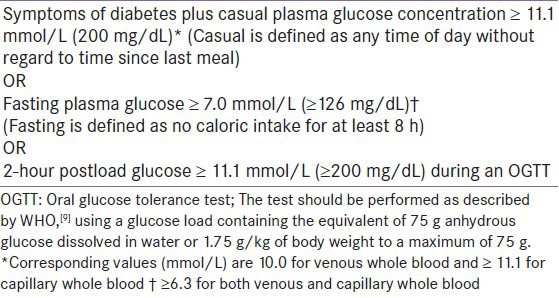

Table 1.

Criteria for the Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus in Children and Adolescents

CHALLENGES IN MANAGEMENT OF T1DM IN CHILDREN

A child with T1DM needs to follow a structured self-management plan including proper insulin use coupled with blood glucose monitoring, physical activity, and a healthy diet. In addition, awareness of diabetes and diabetes care is needed for successful disease management. However, in many parts of the world, especially in developing countries, access to self-care tools including self-management education and to insulin therapy is limited.[1] Low levels of awareness of diabetes and its complications and inadequate physician recommendation of insulin,[10] coupled with financial[11] and emotional burden of the cost of treatment and monitoring equipment, result in poor glycemic control.[12] Poor glycemic control in turn is associated with frequent hyperglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis, dehydration, thrombosis and early death in children with diabetes.[13] Although insulin treatment is life-saving and lifelong, perceived non-flexibility of insulin regimens, in terms of administration and multiple doses, contribute to non-adherence to treatment.[14] The ease of administration and flexibility of use is an important factor affecting the acceptance of treatment recommendations[15] and numerous studies have shown low levels of compliance to therapy.[16,17] Children find using insulin therapy inconvenient due to its perceived interference with eating, exercise and daily routines. In addition, fear associated with hypoglycemia, pain of injection, time required for administration and embarrassment hinder the use of insulin by children.[18] Regular monitoring of blood glucose through self-monitoring devices is insufficiently practised among children as they find it painful and cumbersome.

Diabetes can result in discrimination and may limit social relationships, particularly in children and adolescents, who may find it difficult to cope emotionally with their condition. Children with T1DM often show low levels of compliance to therapy, as they avoid/skip taking injections at school.[16,17] The burden of timely dosing of insulin, religious sensitivities about dietary taboos, and low awareness among teachers about the disease may adversely affect patients’ ability to comply with medical advise.[19]

The problems facing successful T1DM management are further compounded by the benign neglect of T1DM in the public healthcare system. Due to the sheer number of patients with T2DM (i.e. more than 61 million cases in India),[1] T1DM often is relegated to being its “poor cousin” in the matter of receiving administrative attention and allocation of resources. The focus while teaching, managing and allocating resources is always on T2DM; doctors are poorly trained in managing T1DM cases resulting in several long-term implications. The quality of medical education for T1DM is low with an allocation of a maximum of 3 hours for undergraduate- quite generous when compared to the one hour that is deemed necessary as per MCI guidelines. This adds to the lack of knowledge about the management of T1DM among healthcare professionals.

Inadequately trained primary care providers (PCPs) fail to provide quality diabetes care and/or disseminate the information necessary for adequate diabetes awareness. The variable levels of awareness of diabetes among the general public and government is also manifested through the disparity in funding for diabetes seen among different state governments in India. The unique clinical presentations of T1DM coupled with ignorance on the part of the medical community and society in general results in outcomes that are far worse than that seen with T2DM. So there is a need to substantially improve training of HCPs at all levels on this neglected aspect of healthcare.

TREATMENT APPROACH FOR MANAGEMENT OF T1DM

Rationale and implementation

Optimal use of insulin helps to redress the balance between hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia when administered in consideration to the continuous availability of insulin, and assuring access to tools for self-monitoring of blood glucose in order to enable titration of insulin doses based on carbohydrate intake. For ensuring effective T1DM management, it is important to focus on a multidimensional strategy which involves:

Enabling access to insulin and providing tool for the optimal use of insulin in a convenient manner

Tailoring the treatment according to the patient/family convenience

Diabetes education of patient/family to empower them with appropriate information about insulin use

Context-sensitive training and education of HCPs.

Evidence base

The strong relationship between HbA1c levels and long-term complications warrants good glycemic control, early after diagnosis.[20,21,22,23,24] Novel options in insulin therapy are crucial necessity to address efficacy and safety concerns. The basal-bolus concept, as either multiple daily injections or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII), has been shown to give the best results with regard to this aspect.[25,26,27,28] Evidence suggest that rapid-acting analogues given immediately before meals reduce postprandial hyperglycemia as well as nocturnal hypoglycemia.[29] Rapid-acting analogs are approved for pediatric use e.g. insulin as part for children above 2 years, insulin lispro for those above 3 years and insulin glulisine for those above 4 years of age. They also offer the useful option of being given after food when needed (e.g. for infants and toddlers who are reluctant to eat). Insulin detemir is approved for children above 2 years of age and has shown lowest within-subject variability,[30] reduced hypoglycemia rates, improved adherence, and greater treatment satisfaction.[23,28]

With adequate education and support, use of external pumps (CSII) in young infants is successful.[31,32,33,34,35] Combining intensive insulin therapy and glucose sensors with real-time display is associated with a significant improvement of glycemic control, when worn continuously compared to conventional self-monitoring of blood glucose.[36]

Guideline on insulin dosage: At diabetes onset[37]

Day 1 (throughout the night): Give regular insulin every second hour until blood glucose is < 11 mmol/l or (198mg/dL), then every fourth hour.

Dose: <5 years - 0.1 U/kg, 5 years or older 0.2 U/kg. If hourly monitoring of blood glucose cannot be provided, begin with half the above doses.

Day 2 (from morning/breakfast): 0.5-0.75 U/kg/day, distribution of insulin as below: adjust doses daily according to blood glucose levels. The morning (and 3 a.m.) blood glucose is used for adjusting the bedtime basal dose, premeal levels to adjust the daytime basal insulin. Two-hour postprandial blood glucose is used to tailor the meal bolus doses. The breakfast premeal dose is usually the largest bolus dose, due to insulin resistance in the morning.

Insulin needs[37]

During the partial remission phase, the total daily insulin dose is often < 0.5 IU/kg/day.

Prepubertal children (outside the partial remission phase) usually require 0.7-1.0 IU/kg/day.

During puberty, requirements may rise substantially above 1 U/kg/day and even up to 2 U/kg/day.

The “correct” dose of insulin[37]

Achieves the best attainable glycemic control for an individual child or adolescent

Does not cause obvious hypoglycemia problems

Leads to appropriate growth according to children's weight and height charts.

Distribution of insulin dose

Children on twice daily regimens often require around two-thirds of their total daily insulin in the morning and around one-third in the evening.

On this regimen, approximately one-third of the insulin dose may be short-acting insulin and approximately two thirds may be intermediate-acting insulin

On basal-bolus regimens the night-time intermediate- acting insulin may represent between 30% (for regular insulin) and 50% (for rapid-acting insulin) of the total daily insulin dose. Approximately, 50% as rapid-acting or 70% as regular insulin is divided between three to four premeal boluses. When using rapid-acting insulin for premeal boluses, the proportion of basal insulin is usually higher, as regular insulin also provides some basal effect.

Recently introduced rapid-acting analogs are safer and better because of shorter duration of action so higher percentage of basal insulin required as no basal coverage is provided by rapid-acting analogs.

ADDRESSING BARRIERS IN T1DM MANAGEMENT

Ambulatory diabetes care

A team of specialists with expertise in diabetes and pediatrics should care for children with diabetes and their families with an aim to provide:

Specialized hospital care including the diagnosis and initial treatment using established protocols for diabetic ketoacidosis

Comprehensive ambulatory care of diabetes and associated complications and comorbid conditions, including advice on all aspects of the child's home/school care

Thoughtful introduction of new therapies and technologies; emergency access to advice for patients, 24 hours a day.

Insulin treatment

Novel options in insulin therapy with better features, has been a crucial necessity to address the efficacy and safety concerns. Patients either skip doses or take less than the recommended dose due to concerns about the deficiencies in efficacy or safety profile of existing insulins. Independent factors like multiple injections, interference with daily activities, injection pain, and embarrassment play a significant role in insulin omission. To avoid multiple dosing, a truly basal insulin must be designed which requires once daily administration, has a flat profile, which mimics the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic action of physiological insulin and ensures minimal intra-patient variability and longer duration of action.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR INSULIN USE

There is no perfect insulin preparation, but good glycemic control can be reached with insulin suitable to the patients’ needs. The choice of suitable insulin should be individual and based on the desired characteristics of the insulin as well as the availability and cost of the insulin.

Insulin treatment must be started as soon as possible, after diagnosis in all children with hyperglycaemia to prevent metabolic decompensation and DKA.

Multiple subcutaneous injection (MSI) of insulin, is feasible for a majority of patients that minimises the risk of hypos while offering the best control.

The dynamic relationship between carbohydrate intake, physical activity and insulin should be properly communicated to the patient/family from the very first moment.

The insulin selected should be as physiological as possible, but with consideration of the patient's and caregiver's preferences.

Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) should be made available and considered as an essential tool for adjusting insulin doses.

Good technical skill with regard to handling syringes, insulin pens, and pumps must be stressed upon to make insulin administration easier.

Rapid- and long-acting insulin analogs should generally be available, alongside regular (soluble) and NPH insulin.

-

Insulin storage:

- Insulin must never be frozen · Direct sunlight or warming (in hot climates) damages insulin

- Patients should not use insulin that has changed in appearance (clumping, frosting, precipitation, or discoloration)

- Unused insulin should be stored in a refrigerator (4-8°C)

- After first usage, an insulin vial should be discarded after 3 months if kept at 2-8°C or 6 weeks if kept at room temperature.

A basal bolus regimen with regular and NPH insulin should be preferred to pre-mixed insulin preparations. NPH insulin should be given twice daily in most cases, in addition, regular insulin needs to be given 2-4 times daily to match carbohydrate intake.

Pre-mixed insulin may be convenient (i.e. few injections), but they limit the customisation of the insulin regimen, and their use can be difficult in cases where regular food supply is not available.

Insulin pump therapy should be made available and considered wherever suitable.

Severe hyperglycemia detected under conditions of acute infection, trauma, surgery, respiratory distress, circulatory or other stress may be transitory and may require treatment. But it should not in itself be regarded as diagnostic of diabetes.

Screening for diabetes associated antibodies may be useful in selected patients with stress hyperglycemia.

Sick-day guidance

Whenever the child is having a minor illness such as a cold, flu, an upset stomach, emotional stress or any surgical stress, these guidelines can be used:

Test and record of blood sugar (glucose) and urine ketones every 2-4 hours.

-

Check and record of temperature every 4 hours

- If child has a fever (temperature greater than 99.5°F), drink some liquid at least once every half an hour.

- Even if no fever, drink 120 ml of sugar-free, caffeine-free liquid every hour.

-

Call the doctor for any of the following:

- Rising urine ketone levels – if moderate to large.

- Urine ketones present for more than 12 hours.

- Two blood sugar levels in a row higher than 250 mg/dL or lower than 60 mg/dl.

- Vomiting or diarrhea that lasts longer than 6 hours.

- High (101°F) or rising fever or fever for more than 24 hours.

ADDRESSING NUTRITIONAL MANAGEMENT

A specialist pediatric dietician should be involved if possible in giving tailored advice to children and their families about the amount, type and distribution of carbohydrate to be included in regular balanced meals and snacks over the day, to promote optimal growth, development and blood glucose control. This advice should be regularly reviewed to accommodate changes in energy requirements, physical activity and insulin therapy.

Managing diabetic ketoacidosis

Children and adolescents with DKA should be managed in centers with expertise in its treatment and where vital signs, neurological status, and laboratory results can be monitored frequently.

Patient-centric approach

A patient-centric approach of diabetes care must be built, which is sensitive to the needs of patients and their ability to adhere to treatment recommendations.[38,39] Such an approach must respect socio-cultural factors (fasting, religious requirements, etc.) that may play an important role in determining patient attitude to diabetes management.[40] India being a culturally diverse country, keeping the psychosocial factors in mind becomes all the more important. Socio-culturally responsive Indian national guidelines were evolved so that physicians can make treatment decisions accommodating Indian socio-cultural aspects. A greater degree of customization of therapy to individual needs can be achieved through a pool of well-informed and adequately trained paramedical personnel who facilitate better and easier adherence to therapy.[41]

Diabetes education and awareness

It is evident that in order to effectively manage diabetes, comprehensive education encompassing a variety of components of management such as blood glucose monitoring, insulin replacement, diet, exercise, and problem-solving strategies must be delivered to the patient and family. People who are well educated often can manage their diabetes well. An effective diabetes awareness program needs to encompass:

Strategies to reach out to the general population to spread awareness of the disease and its complications.

Educate and reach out to diabetes patients and physicians to improve outcomes.

Public health campaigns led by associations and policy makers to overcome social stigma of T1DM.

Educational programs to educate and sensitize concerned persons in diabetes management must be uniform with respect to content, especially with regard to insulin therapy.[42] There is a need to create space for specialized diabetes educators who will satisfactorily educate patients and their families, and raise awareness of diabetes and insulin therapy.[43] Designing family-centric education programs using a team of HCPs, to address the immediate care environment i.e. the family, will help in encouraging insulin use by patients. Below are 10 best practices for creating awareness of diabetes among public:

Diabetes through media and public posters with catchy phrases like “Jaanch Kijiye Do Jaan Bachayiye” or “Ek Boond Jindagi ke Liye”.

Display visual posters on T1DM in every clinic irrespective of the treatment area across the country.

Inclusion of diabetes and its management as topics of instruction in school curriculum.

Training teachers at school level about the management of diabetes in children.

Launching diabetes oriented short films/movies.

Special incentives to be provided by the government to people with T1DM.

Developing specific websites for T1DM.

Diabetes education through celebrity endorsements.

Printing diabetes awareness messages on train/bus tickets.

Celebration of world diabetes day especially forT1DM.

Training of healthcare professionals

T1DM is a special situation and requires special training of medical fraternity across all levels of healthcare, on a large scale, in all parts of the country. Integrating diabetes education and diabetes treatment protocols within a uniform framework across all levels of healthcare (HCPs, patients and community) will ensure effective care. There is an immediate need for special clinics for T1DM with specialized personnel such as nurses, doctors, and pediatricians for improved prognosis of children with T1DM.

Documentation

Documentation of non-communicable diseases on field, or through cost-effective means such as online registries, is a much needed initiative for obtaining undeniable, logically correct and accurate data. This will facilitate assessment of the current epidemiological status of the disease and the direction of progress of implemented programs. In addition, there is a need to delineate clear mechanisms to comprehensively capture clinical data which in turn is essential for effective advocacy for funding, which gains credibility through proper documentation. In rural areas, if any child is detected with diabetes, it should be made mandatory for schools, hospitals and pharmacies to report to the government for effective data collection. In case pediatric of death in pediatric cases, a verbal autopsy of how the child died should also be undertaken to rule out/ascertain T1DM. All children with onset of diabetes below 14 years age should be categorized as T1DM and should be included in registry. Although, clinical manifestation characterised by presence of ketosis, atypical body mass index (BMI) of < 23.5 kg/m2 and high blood glucose levels are sufficient to confirm T1DM registry cases, there are many other criteria which can be made the basis of inclusion in the registry but may not be a mandated (e.g. C-peptide, test and GAD test).[44] Borderline cases of C peptides should also be included for further diagnostic accuracy. In addition to epidemiological surveys to capture the true state of affairs, case findings beyond registries have to be highlighted for better understanding of the disease state in a country like India.

MANAGING DIABETES IN CHILDREN: THE ROLE OF STAKEHOLDERS

Designing and implementing comprehensive strategies at a scale befitting the T1DM situation in the country requires collaboration and partnership between different constituents with an interest in diabetes care. Multiple partnerships between the government and the private sector in diabetes education should also be explored. There is a strong and unequivocal need for a paradigm shift in the management of T1DM by the medical community, government and society in general. NGOs, religious leaders and school teachers can also play an important role in creating awareness about diabetes as they influence the thought process of a vast majority of population. A multipronged approach is needed to tackle this situation. The roles and steps proposed to achieve this goal are discussed below.

Role of government and policy makers

The government should support the collection and generation of countrywide epidemiological data to capture the true state of the disease along with appropriate socio-economic criteria for proper disease management. Epidemiological surveys should be done, in at least one rural and one urban school, at 4 different geographical locations/population centers to know the true state of the disease in the country. If any child is detected with diabetes, it should be made mandatory for schools, hospitals and pharmacies to report to the government for effective data collection. The government should declare patients with T1DM as being metabolically-challenged and provide them with special privileges such as free admission to any hospital, in case of emergency. Insulin is a lifesaving drug for children with T1DM and thus the government should exempt tax on insulin and ensure its availability at a cost-effective price. Diabetes should be specifically targeted by making provisions for insurance coverage to include patients with T1DM and facilitate equitable access to everyone, regardless of income. Government should be involved in developing comprehensive diabetes care programs and establish “centers of excellence” (e.g. NDCDCS in Andhra Pradesh), which can provide education and support for preventing complications in children with T1DM.

Role of partnerships between various stakeholders

Governments, in partnership with the industry and all other stakeholders, must consider supporting and augmenting the sustainability of programs such as CDiC to enable children with T1DM to have perfectly normal lives as their brethren in other countries. Public health campaigns must be designed to educate the lay public about this disease and its possible management with appropriate medicines, insulin, and education for achieving a normal life for the afflicted. Anganwadi programs like “Choti si asha” should be conducted in rural areas to identify and educate children with T1DM. Doctors, parents and school teachers should take onus for best optimal care. To ensure the delivery of quality care, specified private hospitals and clinics should be designated as centers for free disbursal of insulin, in addition to government hospitals. Furthermore, government along with the industry should encourage special courses for diabetes educators, to manage diabetes in children, and funding research for the development of low cost meters and non-invasive sticks for glucose measurements.

Role of industries

Industries as a part of corporate-social responsibility should be involved in diabetes management programs in the public private partnership (PPP) mode. They should be encouraged to sponsor the treatment cost for children diagnosed with diabetes locally, apart from contributing toward education and awareness programs.

Role of physicians

Physicians should offer free service and run holiday clinics for children with T1DM, particularly for those in the lower socio-economic strata. They should actively be involved in organizing camps for children with T1DM. They should form a link with school teachers and educate them about diabetes and its management in children. If possible, they should rope-in local pathological labs to perform free tests for T1DM as the number of patients is lower when compared to T2DM. Physicians should adopt “Learn globally and think locally approach” and substantially improve the quality of medical education with regards to T1DM considering the disproportionately poor clinical outcomes in this class of patients. Physicians should make use of training manuals from ISPAD and CDiC websites that are available free of cost. Training programs for paramedics and healthcare professionals for diabetes specific situations such as diagnosis, treatment, and management of children with T1DM should be undertaken by associations and government.

CONCLUSIONS

While T1DM has been traditionally seen as a minor concern in the larger picture of pediatric ailments, new data reveals that the incidence of T1DM has assumed alarming proportions. It has long been clear that while the disease may be diagnosed at an early age, its impact is not isolated to afflicted children. The direct impact of the disease on the patient is debilitating due to the nature of the disease and lack of proper access to treatment in India. But this impact is further compounded by the utter apathy and often times antipathy, which patients withT1DM have to face.

Lack of awareness of the issue in all stakeholders, low access to quality healthcare, patient, physician and system level barriers to the delivery of optimal diabetes care are some of the factors which hinder successful management of T1DM. With coordinated action by all the stakeholders, effective mechanisms to manage T1DM can be evolved. This must be a priority that should occupy our foremost thoughts to achieve the ultimate goal of “No child should die of diabetes”.

CONSENSUS STATEMENT

List of participants

Dr. A K Das, Dr. Abdul Jaleel M, Dr. Ajay Hanumanthu, Dr. Ajish T P, Dr. Ajit Kumar Goyal, Dr. Alexandra Greene, Dr. Alka Chadha, Dr. Alok Kanungo, Dr. Amarendra Pragad Singh, Dr. Ananth B M, Dr. Ananthala Upendra bai, Dr. Aniket V Inamdar, Dr. Anil Vijayakumar, Dr. Animesh Maiti, Dr. Aniruddha Umarji, Dr. Anjana Hulse, Dr. Annappa A Pangi, Dr. Anubhav Thubral, Dr. Appasaheb V Kadam, Dr. Archana Sarda, Dr. Archith Boloor, Dr. Arshith Sujay B, Dr. Arun Krishna, Dr. Aruyerchelvan R, Dr. Asha H S, Dr. Ashok Kumar M, Dr. Ashok R Sonnar, Dr. Aswathamma N, Dr. Atul Gupta, Dr. B A Hanumanthu, Dr. B D Shashidhar, Dr. Babruwad Ramesh G, Dr. Baburajendra B Naik, Dr. Balachandran V, Dr. Basavaraj R Patil, Dr. BaskerWN, Dr. Bedowra Zabeen, Dr. Bhaskar Ganguli, Dr. Bhatt Kalpak, Dr. Bhavya Hari, Dr. Bipin K Sethi, Dr. Boochandran T S, Dr. Bui Phuong Thao, Dr. C Ramachandra Bhat, Dr. Capt. V S Prabhakar, Dr. Cecil C Khakha, Dr. Chalageri H K, Dr. Chandni R, Dr. Chandraprabha S, Dr. Chandrasekhar P, Dr. Chandrashekar M A, Dr. Charles Antony Pillai, Dr. Chetan Srinivas, Dr. Chethana B S, Dr. Chidananda S C, Dr. Chitra S, Dr. D Sen Purkayastha, Dr. D Thankam, Dr. Darivemula Anilkumar, Dr. Dayananda G, Dr. Debasis Bose, Dr. Dee Ann Stanly, Dr. Deepa S, Dr. Deepak S Jadhav, Dr. Deepak Yagnik, Dr. Dehayem Yefou Mesmin, Dr. Devendra Chavan M, Dr. Dhawde Sharad P, Dr. Dhruvi J Hasnani, Dr. Dilipkumar Kandar, Dr. Dipti Sarma, Dr. Diwakar, Dr. Drsharath Madhyastha, Dr. Eldose T Vargese, Dr. Eluru Stephen, Dr. Eswar Prasad S, Dr. Fauzia Mohsim, Dr. Franklin Joseph, Dr. Ganapathy S, Dr. Gangakhed Satish Kumar, Dr. Gaurav Chaudhary, Dr. Gayathri L, Dr. George Thoduka, Dr. Go Bharani, Dr. Govind Rajgarhit, Dr. Gururaj Sattur, Dr. Gururaja Rao K, Dr. H C Gangadhar, Dr. Hareesh K, Dr. Harijanakiraman, Dr. Harikrishna Singh, Dr. Hariprasanna, Dr. Harsha N S, Dr. Hema M, Dr. Hema Prabhu, Dr. Hiren Pravinbhai Patt, Dr. Honnaiah Siddappa, Dr. I P S Kochar, Dr. Indrasen Reddy P, Dr. Iran Thi Bich Huyen, Dr. J S Kumar, Dr. Jayakumar, Dr. Jayaprakash Sai, Dr. Jijith Krishnan, Dr. Joison Abraham, Dr. K G Prakash, Dr. K L Udapudi, Dr. K M Prasanna Kumar, Dr. Kalpana Dash, Dr. Kalpana Thai, Dr. Karthik Rao N, Dr. Katkar Shashikant, Dr. Kavitha Aditya Khatod, Dr. Kesavaramana, Dr. Khaled Junaidi, Dr. Khandige G K, Dr. Kiran Kinger, Dr. KirankumarMK, Dr. Krishna MurthyMN, Dr. Krishna Rajendra, Dr. Krishnaswamy B L, Dr. Kyaw Myo, Dr. Lakkanna S, Dr. Lakshmamma S N, Dr. Lakshmanan S S, Dr. Lakshmi V, Dr. Lakshmi V Reddy, Dr. Laxman Giddiyavar, Dr. Louis George, Dr. M C Koshy, Dr. Madhu Prasad K V, Dr. Mahalakshmi, Dr. Mahantesh P Gadag, Dr. Mahendra, Dr. Mahesh V, Dr. Manoj Chadha, Dr. Meenakumari Mohan, Dr. Mir Iftekhar Ali, Dr. Mirza Aziz Baig, Dr. Mobashshir Heyat, Dr. Mohammed Zia Rahaman, Dr. Mohan, Dr. Mridulbera, Dr. Muraleedhar L, Dr. Muralidhara D, Dr. Muralidhara Krishna C S, Dr. Mythili Ayyagari, Dr. N Rayees Ahmed, Dr. N S Prasad, Dr. N S Ramesh, Dr. Nagesh S Adiga, Dr. Naina Bhat, Dr. Naveen, Dr. Navoda Atapattu, Dr. Neeta Rohit Deshpande, Dr. Nitin Subrav Gade, Dr. Noor Khan, Dr. P V Ajith Kumar, Dr. P V Rao, Dr. P. Madialagan, Dr. P. Sankar, Dr. PathyVNV, Dr. Pavana, Dr. Pawan K R Goyal, Dr. Piyush Ashok Chaudhari, Dr. Poonam Singh, Dr. Prabhat Kumar Jha, Dr. Prabhavathi M, Dr. Prabhu S, Dr. Pradnya Kamble, Dr. Pramita Vadavi, Dr. Pramod Govardhan Katti, Dr. Prasad J S, Dr. Praveen Ramachandra, Dr. Prema R, Dr. Premkumar A, Dr. Priya Mani, Dr. Pushpa Krishna, Dr. Pushpa Ravikumar, Dr. Radha Unnikrishnan, Dr. Rafiq Ahmed K, Dr. Raghavendra B M, Dr. Raghunath Sharma, Dr. Rajakumar R, Dr. Rajeev Agarwal, Dr. Rajesh Joshi, Dr. Rajesh Kumar J, Dr. Rajiv Garg, Dr. Rajiv Kasiviswanath, Dr. Rajnanda Desai, Dr. Rajneesh Mittal, Dr. Rama Krishnan K, Dr. Ramachandran V A, Dr. Raman K V, Dr. Ramesh Babu, Dr. Ramesh Chandrasekaran, Dr. Ranjit Kumaruhatua, Dr. Ravi Katkar, Dr. Rehana Begum, Dr. Reshma B V, Dr. Revadi S S, Dr. S S Srikanta, Dr. S Vijaya Bhaskar Reddy, Dr. Sabeer A Rasheed, Dr. Sabeer T K, Dr. Sabita Mishra, Dr. Sabu Paul, Dr. Sai Pradeep, Dr. Sameena Banu, Dr. Sameer Aggarwal, Dr. Samin Tayyeb, Dr. Sandhya Kulkarni, Dr. Sandip Mandal, Dr. Sanghita Dasgupta, Dr. Sanjay Gupta, Dr. Sanjay Kalra, Dr. Sanjay Reddy, Dr. Sanjay S, Dr. Sanjeev Chetty, Dr. Santhosh Olety, Dr. Santosh Kumar P K, Dr. Sarita Ramachandran, Dr. Sashidhar Buggi, Dr. Sathish K B, Dr. Sathiss Rajan, Dr. Sathya Prakash, Dr. Saurabh Mishra, Dr. Saurabh Sharma, Dr. Seetharam Buddhavarapu, Dr. Selva Rajan M, Dr. Selvaraj V, Dr. Seshasayanan R N, Dr. Shachin K Gupta, Dr. Sham Mukundan, Dr. Shankar Alingaiah, Dr. Shankar Javarayi Gowda, Dr. Sharwari Paranjape, Dr. Sheila Baskar, Dr. Shetty K J, Dr. Shivaprasad C, Dr. Siddaraj K S, Dr. Somnath Mitra, Dr. Spandan Bhadury, Dr. Sreejith N Kumar, Dr. Sri Hari Reddy, Dr. Sridhar D, Dr. Sridhar S, Dr. Srinivas A N, Dr. Srinivas B, Dr. Subhankar Chowdhury, Dr. Sujaykumar Mukhopadhyay, Dr. Sumathi K, Dr. Sundar Rao CH, Dr. Suneel Kumar L, Dr. Sunil Bohra, Dr. Sunil K Menon, Dr. Sunitha Vidyanand, Dr. Sunu Kurian, Dr. Sureendar Pedamalla, Dr. Suresh Damodharan, Dr. Suresh Devatha, Dr. Suresh Harsoor, Dr. Suresh Hegde, Dr. Suresh Nayak B, Dr. Suresh SM, Dr. Swati Sachin Jadhav, Dr. Syed A Javaz, Dr. Syed Muneer, Dr. Tadi Geetha Prasadini, Dr. Tripty Singh, Dr. Uditha Bulugahapitiya, Dr. Usha Rani R, Dr. V. Ravindranath, Dr. V.C. Nirmala, Dr. Vageesh S, Dr. Vaidehi Dande, Dr. Vasanthi Nath, Dr. Vasu S, Dr. Veena Sreejith, Dr. Venkatakrishna Rao U, Dr. Venkateswarlu D, Dr. Venugopal Rao V, Dr. Vidyadhara Shetty, Dr. Vijay Viswanathan, Dr. Vijaya Sarathi H A, Dr. Vijaya Vardhan R A, Dr. Vijayakumar K, Dr. Vijayashankar S, Dr. Vijaykumar P, Dr. Vimal Kumar Varma, Dr. Vinay Kumar, Dr. Yalamanchi Sadasiva Rao, Dr. Yashdeep Gupta, Dr. Zacharia P S, Dr. Suryanarayana V

A panel 294 eminent doctors

The first international consensus meet on diabetes in children was convened with the aim of providing a common platform to all the stakeholders in the management of T1DM, to discuss the academic, administrative, and healthcare system-related issues. The ultimate aim was to articulate the problems faced by children with diabetes in a way that centralized their position and focused on creating modalities of management sensitive to their needs and aspirations. It was conceptualized to raise a strong voice of advocacy for improving the management of T1DM and ensuring that “No child should die of diabetes”.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Jeevan Scientific Technology Limited for providing editorial assistance in the development of this manuscript. The proceedings and consensus statement has been published in the form of a book titled, “Diabetes in Children.”

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1. [Last accessed on 2013 Jan 20]. Available from: http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas/5e/diabetes-inthe-young .

- 2.Mannering SI, Wong FS, Durinovic-Belló I, Brooks-Worrell B, Tree TI, Cilio CM, et al. Current approaches to measuring human islet-antigen specific T cell function intype 1 diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;162:197–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalra S, Kalra B, Sharma A. Prevalence of type 1 diabetes mellitus in Karnal district, Haryana state, India. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2010;2:14. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asha BP, Murthy BN, Chellamariappan M, Gupte MD, Krishnaswami CV. Prevalence of known diabetes in Chennai City. J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:974–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar P, Krishna P, Reddy SC, Gurappa M, Aravind SR, Munichoodappa C. Incidence of type 1 diabetes mellitus and associated complications among children and young adults: Results from the Karnataka Diabetes Registry 1995-2008. J Indian Med Assoc. 2008;106:708–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Misra P, Upadhyay RP, Misra A, Anand K. A review of the epidemiology of diabetes in rural India. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;92:303–11. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valerio G, Licenziati MR, Tanas R, Morino G, Ambruzzi AM, Balsamo A, et al. Gruppo di Studio Obesità Infantile della Società Italiana di Endocrinologia e Diabetologia Pediatrica. [Management of children and adolescents with severe obesity] Minerva Pediatr. 2012;64:413–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao M, Prasek M, Metelko Z. Organization of diabetes health care in Indian rural areas. Diabetol Croat. 2002:31–3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geneva: World Health Organisation; Tech. Rep. Ser. no. 646-1; World Health Organization: WHO Expert Committee on Diabetes Mellitus. Second Report. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saudek CD, Rastogi R. Assessment of glycemia in diabetes mellitus-self-monitoring of blood glucose. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:809–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chudyk A, Shapiro S, Russell-Minda E, Petrella R. Self-monitoring technologies for type 2 diabetes and the prevention of cardiovascular complications: Perspectives from end users. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2011;5:394–401. doi: 10.1177/193229681100500229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joshi SR, Das AK, Vijay VJ, Mohan V. Challenges in diabetes care in India: sheer numbers, lack of awareness and inadequate control. J Assoc Physicians India. 2008;56:443–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmad J, Pathan MF, Jaleel MA, Fathima FN, Raza SA, Khan AK, et al. Diabetic emergencies including hypoglycemia during Ramadan. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:512–5. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.97996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez JS, Peyrot M, McCarl LA, Collins EM, Serpa L, Mimiaga MJ, et al. Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2398–403. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Kruger DF, Travis LB. Correlates of insulin injection omission. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:240–5. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lahiri SK, Haldar D, Chowdhury SP, Sarkar GN, Bhadury S, Datta UK. Junctures to the therapeutic goal of diabetes mellitus: Experience in a tertiary care hospital of Kolkata. J Midlife Health. 2011;2:31–6. doi: 10.4103/0976-7800.83271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagpal J, Bhartia A. Quality of diabetes care in the middle- and high-income group populace: The Delhi Diabetes Community (DEDICOM) survey. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2341–8. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Lauritzen T, Skovlund SE, Snoek FJ, Matthews DR, et al. ; International DAWN Advisory Panel. Resistance to insulin therapy among patients and providers: Results of the cross-national Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes, and Needs (DAWN) study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2673–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vasan SK, Karol R, Mahendri NV, Arulappan N, Jacob JJ, Thomas N. A prospective assessment of dietary patterns in Muslim subjects with type 2 diabetes who undertake fasting during Ramadan. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:552–7. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.98009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rewers M, Pihoker C, Donaghue K, Hanas R, Swift P, Klingensmith GJ. Assessment and monitoring of glycemic control in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009;10(Suppl 12):S71–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donaghue KC, Chiarelli F, Trotta D, Allgrove J, Dahl-Jorgensen K. Microvascular and macrovascular complications associated with diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009;10(Suppl 12):S195–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kordonouri O, Maguire AM, Knip M, Schober E, Lorini R, Holl RW, et al. Other complications and associated conditions with diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009;10(Suppl 12):S204–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Australian Government: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2005. APEG. (Australasian Paediatric Endocrine Group). Australian Clinical Practice Guidelines: Type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silverstein J, Klingensmith G, Copeland K, Plotnick L, Kaufman F, Laffel L, et al. ; American Diabetes Association. Care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: A statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:186–212. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of longterm complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Effect of intensive diabetes treatment on the development and progression of long-term complications in adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. J Pediatr. 1994;125:177–88. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White NH, Cleary PA, Dahms W, Goldstein D, Malone J, Tamborlane WV Diabetes Control and Complication Trial (DCCT)/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) Research Group. Beneficial effects of intensive therapy of diabetes during adolescence: Outcomes after the conclusion of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) J Pediatr. 2001;139:804–12. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.118887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bangstad HJ, Danne T, Deeb L, Jarosz-Chobot P, Urakami T, Hanas R. Insulin treatment in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009;10(Suppl 12):82–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ford-Adams ME, Murphy NP, Moore EJ, Edge JA, Ong KL, Watts AP, et al. Insulin lispro: A potential role in preventing nocturnal hypoglycaemia in young children with diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2003;20:656–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danne T, Datz N, Endahl L, Haahr H, Nestoris C, Westergaard L, et al. Insulin detemir is characterized by a more reproducible pharmacokinetic profile than insulin glargine in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: Results from a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Pediatr Diabetes. 2008;9:554–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2008.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson DM. Progress in the treatment of childhood diabetes mellitus and obesity. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2002;15(Suppl 2):S745–9. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.2002.15.s2.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brink S, Laffel L, Likitmaskul S, Liu L, Maguire AM, Olsen B, et al. Sick day management in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009;10(Suppl 12):S146–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doyle EA, Weinzimer SA, Steffen AT, Ahern JA, Vincent M, Tamborlane WV. A randomized, prospective trial comparing the efficacy of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion with multiple daily injections using insulin glargine. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1554–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.7.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.García-García E, Galera R, Aguilera P, Cara G, Bonillo A. Long-term use of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion compared with multiple daily injections of glargine in pediatric patients. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2007;20:37–40. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2007.20.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phillip M, Battelino T, Rodriguez H, Danne T, Kaufman F European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology; Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society; International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes; American Diabetes Association; European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Use of insulin pump therapy in the pediatric age-group: Consensus statement from the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology, the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society, and the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes, endorsed by the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1653–62. doi: 10.2337/dc07-9922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamborlane WV, Beck RW, Bode BW, Buckingham B, Chase HP, Clemons R, et al. Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Continuous Glucose Monitoring Study Group. Continuous glucose monitoring and intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1464–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.2011 Global IDF/ISPAD Guideline for Diabetes in Childhood and Adolescence. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 25]. Available from: http://www.idf.org .

- 38.Williams GC, McGregor H, Zeldman A, Freedman ZR, Deci EL, Elder D. Promoting glycemic control through diabetes self-management: Evaluating a patient activation intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baruah MP, Kalra B, Kalra S. Patient centred approach in endocrinology: From introspection to action. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:679–81. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.100629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Osman A, Curzio J. South Asian cultural concepts in diabetes. (30-2).Nurs Times. 2012;108:28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagner EH, Grothaus LC, Sandhu N, Galvin MS, McGregor M, Artz K, et al. Chronic care clinics for diabetes in primary care: A system-wide randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:695–700. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murugesan N, Shobana R, Snehalatha C, Kapur A, Ramachandran A. Immediate impact of a diabetes training programme for primary care physicians-an endeavour for national capacity building for diabetes management in India. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;83:140–4. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soundarya M, Asha A, Mohan V. Role of a diabetes educator in the management of diabetes. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2004;24:65–8. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feng YF, Yao MF, Li Q, Sun Y, Li CJ, Shen JG. Fulminant type 1 diabetes in China: A case report and review of the literature. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2010;11:848–50. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1000080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]