Abstract

The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act exempted menthol from a flavoring additive ban, tasking the Tobacco Products Safety Advisory Committee to advise on the scientific evidence on menthol. To inform future tobacco control efforts, we examined the public debate from 2008 to 2011 over the exemption. Health advocates regularly warned of menthol’s public health damages, but inconsistently invoked the health disparities borne by African American smokers. Tobacco industry spokespeople insisted that making menthol available put them on the side of African Americans’ struggle for justice and enlisted civil rights groups to help them make that case. In future debates, public health must prioritize and invest in the leadership of communities most affected by health harms to ensure a strong, unrelenting voice in support of health equity.

Menthol flavoring in tobacco remains a top public health concern.1 Because menthol makes smoking less irritating, menthol cigarettes can act as a starter product2 for adolescents: nearly half of smokers aged 12 to 17 years use menthol cigarettes compared with less than a third of smokers older than 26 years.3 Smoking menthol cigarettes is also linked with higher rates of disease4 and lower rates of cessation, especially among African American smokers.5

In the 1960s, the tobacco industry began a campaign of “masterful manipulation” targeting menthols to African Americans.6 By 2008, 83% of African American smokers smoked menthol cigarettes compared with 24% of White smokers.3 African Americans bear a disproportionate share of smoking-related health consequences7,8 even though they smoke at similar rates as White Americans, suggesting that menthol cigarettes may confer greater health harms.4 Cigarettes marketed as menthol constitute more than a quarter (28%) of the US cigarette market,9 including leading brands Newport (Lorillard) and Marlboro Menthol (Philip Morris).10

In 2009, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (FSPTCA)11 authorized the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to regulate tobacco products.12,13 The law also established the Center for Tobacco Products, and Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC). Though hailed by some commentators as an important tobacco control opportunity,14 the legislation controversially excluded menthol from an immediate ban on flavoring additives in cigarettes.15 As a concession for the exemption, TPSAC’s first order was to make a recommendation about menthol to the FDA on the basis of the available scientific evidence.

In March 2011, TPSAC concluded that the “removal of menthol cigarettes from the marketplace would benefit the public health in the United States.”16(p225) In July 2013, the FDA released a preliminary scientific evaluation on the public health effects of menthol, confirming menthol’s harmful effects on smoking initiation and cessation, and called for public comment on the report.17 In September 2013, the FDA extended the public comment period for an additional 60 days,18 with any potential rulemaking to be announced after that time.

We analyzed the policy debate over whether to ban menthol flavoring in cigarettes. We examined, in news coverage and committee proceedings, the arguments made by ban proponents and opponents on this question from the passage of the act through TPSAC’s review of the scientific evidence. We examined how racial disparities in African American use of and health harms from menthol cigarettes were portrayed and whether racial arguments were used in the debate.

Regulatory proceedings are a significant source of information about policy debates19; investigating them has established the tobacco industry’s long history of efforts to weaken or defeat regulation of their products by health advocates.20–22 News coverage influences policy debates by setting the agenda for the public and policymakers,23–25 and framing the terms of those debates.26,27 Analyzing news coverage and regulatory documents can reveal the full range of speakers and how they present arguments that advance their divergent goals to policymakers and the public.28

METHODS

We conducted a content analysis of arguments made during the passage of the act and committee proceedings on menthol, including (1) news coverage of the menthol policy debate from 2008, when the exemption was proposed, through the release of the TPSAC report, (2) documents submitted to TPSAC, and (3) transcripts of TPSAC meetings.

Sample Selection

We sampled coverage from 28 sources: 8 national papers, a leading newspaper from each of 6 major tobacco-producing states, and 14 African American publications (Appendix A, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org). We analyzed newspapers because, despite their declining readership, they serve the key agenda-setting function for policymakers and for other media, including TV and social media.29 We searched these sources for articles, editorials, op-eds, letters to the editor, and blog posts including the keyword “menthol” published between January 1, 2008, and June 1, 2011. We eliminated duplicates and irrelevant articles (e.g., food columns that described a wine’s “menthol flavor”).

Using committee hearing agendas and the manual index search on the Center for Tobacco Products’ Web site,30 we located relevant documents submitted to the committee, as well as presentations given during TPSAC meetings from March 1, 2010, through March 31, 2011. Because of the volume of material presented to the TPSAC, we selected only documents that addressed 1 or more topics central to menthol regulation: mentholated cigarettes’ health harms, health disparities facing youths and African American menthol smokers, the potential of banning menthol to produce a black market or other unintended consequences, and concerns over restrictions on consumers’ freedom of choice.

Coding the Sample

Trained coders assessed all selected news and TPSAC documents by identifying the author’s name, publication date, publication name, document type (news vs TPSAC submission), and slant on banning menthol (favored, opposed, or mixed). Following an iterative process,31 coders assessed the frames in each story to refine an instrument we developed for a previous content analysis of similar material.19 Krippendorff’s α32 on all measures for news documents was 0.73 or greater, and 0.75 or greater for TPSAC documents (Figure A, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org).

For all frames, coders recorded the speaker and whether the speaker argued for or against banning menthol. Each frame invocation could only have 1 valence, but across the documents a frame could be used with both valences. For example, different speakers used the claim that “Menthol usage is high among African Americans” to support or oppose banning menthol.

For news documents, the sentence was the primary unit of analysis26; if multiple frames appeared in a sentence, we recorded all instances of each frame. The TPSAC documents were extremely long and unwieldy to code sentence by sentence; we captured any frames that occurred at least once per document. Following the news methodology, we recorded each frame appearing within a single sentence, and coded sentence fragments that appeared in a bulleted list of scientific findings. To assess variations among frames used and speakers quoted, we conducted a 2-sample proportion test with Stata software version 13.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

We found 199 relevant news articles and 154 TPSAC documents (Table 1). Most news articles presented a mix of perspectives for and against banning menthol (71%), and nearly half of TPSAC documents advocated against a ban (44%).

TABLE 1—

Slant of News and Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee Documents on Banning Menthol: United States, 2008–2011

| Documents | Against Ban, % | For Ban, % | Mixed, % |

| News (n = 199) | |||

| National newspapers (n = 117) | 6 | 14 | 80 |

| Tobacco state newspapers (n = 46) | 15 | 11 | 74 |

| African American media (n = 36) | 33 | 28 | 39 |

| % of all news documents | 13 | 16 | 71 |

| TPSAC (n = 154) | |||

| Scientific report (n = 71) | 21 | 37 | 42 |

| Letter (n = 40) | 55 | 43 | 3 |

| Nonscientific report (n = 35) | 67 | 25 | 8 |

| E-mail submission (n = 8) | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| % of all TPSAC documents | 44 | 34 | 22 |

Note. TPSAC = Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. Not all totals add to 100% because of rounding.

Balanced News Coverage of Menthol Policy

National newspaper articles and those from tobacco state newspapers included both sides of the debate (80% and 74%, respectively), though in tobacco states antiban pieces outnumbered proban coverage. Less than half (39%) of African American news and blog coverage was mixed, with slightly more antiban than proban pieces.

The most common TPSAC documents (46%) were scientific reports offering original evidence or reviewing the scientific literature on menthol cigarettes, including 6 white papers commissioned from University of California scholars reviewing internal documents for tobacco industry knowledge of menthol’s health harms.33–38 Most letters—formal communications submitted to the committee—were antiban, such as the National Association of Convenience Stores’ submission about a ban’s potential economic consequences.39 Nonscientific reports (23%) analyzed policy consequences of banning menthol, such as modeling a ban’s health effects.

The scientific practice of acknowledging all evidence, even if contrary, helps explain the antiban preponderance among TPSAC documents. Although private health authorities authored the most submissions, only a modest majority (58%) submitted exclusively proban documents, and the remainder presented the strengths and weaknesses of evidence on menthol’s public health harms. By contrast, industry submissions never allowed for unique menthol-related harms, and only presented arguments against a ban.

The Evolution of the Menthol Debate in the News

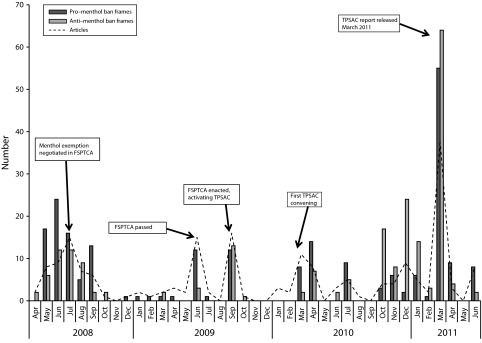

From 2008 to 2011, news coverage of the menthol debate shifted from proban during the act to antiban as TPSAC deliberated (P < .01; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Pro– and anti–menthol ban frames (n = 442) and articles (n = 199) in news coverage of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act and Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee: United States, 2008–2011.

Note. FSPTCA = Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; TPSAC = Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee.

News coverage of the act peaked in mid-2008, when language of the bill was being negotiated.40 In June 2009, passage of the act generated a brief flurry of coverage that was almost completely proban.

Coverage around the first TPSAC convenings41 was primarily proban; this shifted around the October 7, 2010, meeting when internal tobacco industry documents on menthol were reviewed.42 From then until the committee released its findings, antiban frames dominated every spike in coverage. Proban arguments reappeared with coverage of the TPSAC report.

Menthol in Act News

Debate over the act in news coverage was mostly balanced, led modestly by proban arguments (Table 2).

TABLE 2—

Percentage of Arguments in News and Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee Documents on Banning Menthol: United States, 2008–2011

| Arguments | FSPTCA News (Apr 2008–Jun 2009; n = 142), % | TPSAC News (Jul 2009–Jun 2011; n = 300), % | TPSAC Documents (Jul 2009–Jun 11; n = 235), % |

| Proban | |||

| Ban would improve public health | 21 | 24 | 8 |

| Tobacco industry targets African Americans, youths | 8 | 3 | 11 |

| Menthol cigarettes are uniquely dangerous | 6 | 10 | 14 |

| Menthol cigarettes contribute to health disparities | 3 | 2 | 9 |

| Industry negotiates in bad faith | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Proban total | 39 | 40 | 42 |

| Antiban | |||

| Ban would create a black market | 16 | 22 | 14 |

| Ban would harm industry, government revenue | 6 | 8 | 9 |

| Ban would harm freedom, choice | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Menthol not uniquely dangerous | 5 | 5 | 9 |

| Menthol science is uncertain | 3 | 6 | 8 |

| Antiban total | 35 | 46 | 44 |

| Racial bias | |||

| Proban: policy discriminates against African American smokers | 18 | 4 | 3 |

| Antiban: policy discriminates against African American smokers | 2 | 8 | 0 |

| Proban: menthol usage is high among African American smokers | 6 | 0 | 9 |

| Antiban: menthol usage is high among African American smokers | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Racial bias total | 27 | 14 | 15 |

Note. FSPTCA = Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; TPSAC = Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. Columns do not add to 100% because of rounding.

Arguments for banning menthol.

Private medical and public health authorities frequently voiced the key argument that banning menthol would benefit public health (Table 3). Few health spokespeople expressed antiban positions, though the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids suggested that an immediate ban “would negatively impact the public’s health.”43

TABLE 3—

Prevalence (%) of Speakers Quoted in Menthol Policy News Coverage and Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee Documents: United States, 2008–2011

| Speaker | FSPTCA News (Apr 2008–Jun 2009; n = 142), % | TPSAC News (Jul 2009–Jun 2011; n = 300), % | TPSAC Documents (Jul 2009–Jun 2011; n = 235), % |

| Private health authority (doctors and health NGOs) | 46 | 18 | 43 |

| Industry representative | 16 | 20 | 25 |

| Opinion author | 11 | 12 | 0 |

| Elected official | 11 | 1 | 3 |

| Nonelected official (FDA, Public Health Service) | 4 | 14 | 4 |

| Nonattributed (journalist) | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Advocacy groups | 3 | 22 | 15 |

| Nonindustry business representative | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| Concerned citizen | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Worker or employee | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Plaintiff lawyer | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Note. FDA = US Food and Drug Administration; FSPTCA = Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; NGO = nongovernmental organization; TPSAC = Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. Columns do not add to 100% because of rounding.

Ban advocates cited the tobacco industry’s history of targeting menthol cigarettes to vulnerable consumers, claiming that menthol brands “are products designed specifically to lure young blacks into a lifetime of tobacco use.”44 They emphasized the unique harms of menthol, especially in aiding initiation and impeding cessation of smoking. Supporters occasionally articulated how menthol exacerbates health disparities for African Americans, or how the industry could not be trusted to negotiate compromises like the menthol exemption.45

Arguments against banning menthol.

The tobacco industry led ban opposition during the act debate (Table 3); its main claim was that a menthol ban would create a black market (Table 2). Lorillard executive Martin Orlowsky went so far as to invoke terrorism:

There is ample evidence that criminal enterprises and terrorist organizations already find the profit from black market cigarettes easy to generate and conceal. And that’s when the product is legal everywhere, and the only differences in availability are the taxes from one jurisdiction to another.46

Other opponents, such as Representative John Dingell (D–MI), threatened economic losses: “In a perfect world, we’d ban all cigarettes. But the hard fact is that there are a lot of jobs depending on this.”47 Detractors such as the Congress of Racial Equality’s Niger Innis also tied a ban to government overreach into consumer freedoms:

Yet government efforts to demonize menthol flavored cigarettes will inevitably lead to adding yet another government imposed prohibition on a legal activity, hence another government restriction on people’s ability to exercise their liberty.48

Led by industry spokespeople, opponents made 2 criticisms against the science used to support a ban. They defended mentholated cigarettes as not measurably more harmful than nonmentholated cigarettes, and suggested that whatever evidence existed was uncertain enough to render a ban unwarranted.

Racial bias.

Both sides evoked racial bias to contest whether banning or exempting menthol discriminated against African American smokers. In act news coverage, 90% of the arguments invoking racial bias were proban. A widely reported statement from the National African American Tobacco Prevention Network and former health secretaries Joseph Califano and Louis Sullivan claimed the exemption

discriminates against African-Americans—the segment of our population at greatest risk for the killing and crippling smoking-related diseases. . . . It sends a message that African American youngsters are valued less than white youngsters.49

Writer Paul Smalera added that the exemption “practically paints a bull’s-eye on the lungs of African-American smokers.”50 Ban proponents also cited statistics on African American smokers’ disproportionate menthol use to criticize the exemption.

A few speakers used discrimination to support antiban positions, as when Atlanta Journal-Constitution columnist Jim Wooten criticized proban advocacy as race baiting: “Goodness gracious. Just plain goodness gracious. Is there no race card we won’t play to win an election, legislation or policy debate?”51 Opponents also argued that a ban should not be justified on the basis of the demographic composition of menthol’s smokers.

Menthol in TPSAC News

News coverage more than doubled after TPSAC was convened as fewer private health authorities spoke (P < .01) and the industry’s presence rose. Advocacy groups—often including African American organizations allied with the tobacco industry52,53—became a significantly larger presence in the news (P < .01).

Arguments for banning menthol.

Proponents continued to argue most often that banning menthol carried few risks and would benefit public health. The conclusion by TPSAC that the “removal of menthol cigarettes from the marketplace would benefit the public health in the United States”16(p225) was widely quoted in the news. Ban supporters also increasingly spoke about menthol’s unique health harms. The Los Angeles Times editorialized about menthol’s role in stalling tobacco control progress, noting, “Studies have found that menthol makes it easier for young smokers to get started and harder for habitual smokers to stop.”54

During this period we found fewer arguments about the importance of protecting African American smokers’ health, whether from tobacco industry predatory targeting practices or menthol-related health disparities. One of the few proban groups quoted during this period, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Legal Defense and Education Fund, called industry’s statements that smokers deserve the right to choose menthol cigarettes “so hypocritical it’s unbelievable” because “Addiction is the absolute opposite of choice.”55 Occasionally proban speakers accused the industry of acting in bad faith and undermining the policy process.56

Arguments against banning menthol.

During TPSAC deliberations, opponents’ arguments consolidated around the black market, increasingly voiced by a set of African American organizations with a history of tobacco industry ties.52 Through widely quoted opinion pieces, they invoked the legacy of discriminatory treatment of African Americans to criticize a ban. The Congress of Racial Equality’s Innis denounced “the federal government acting as Big Daddy to individuals exercising a legal choice.”57 Malik Aziz of the National Black Police Association suggested that an illicit market would worsen health harms, especially for youths:

[I]f menthol cigarettes are banned, contraband versions mimicking name brands will enter the flourishing illegal market. These new unregulated illegal products would be sold in cigarette houses, on corners, in cars and back alleyways. Who will ask the young smoker to present identification in the back alley or at the door of a vehicle?58

Jessie Lee of the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives argued that a ban would deepen policing inequities suffered by African American communities.59 News publications began to suggest that antiban organizations “echoed Lorillard’s argument that a menthol ban would lead to a contraband market for menthol cigarettes.”55

Racial bias.

During TPSAC’s process, two thirds of discrimination arguments claimed that a ban would be biased against African Americans. Lorillard even portrayed ban opposition as part of the struggle for Black liberation, claiming, “the history of African Americans in this country has been one of fighting against paternalistic limitations and for freedoms.”60 The few proban arguments invoking discrimination blasted the exemption. As tobacco control leader Carol McGruder wrote,

Though 95% of young Black smokers initiate smoking with mentholated cigarettes, the health and welfare of these young people were not a priority of the legislation.56

Menthol in TPSAC Documents

In documents submitted to TPSAC, proponents shifted from touting a ban’s health benefits to voicing concerns over the tobacco industry’s, and menthol’s, impact on African American smokers’ health (Table 2). Private health authorities were again the most prevalent speakers. Antiban advocates were joined by non–tobacco industry business representatives before the committee (Table 3). Compared with the news, the discrimination discussion dissipated, though both sides invoked African American smokers’ disproportionate menthol use.

Arguments for banning menthol.

In committee documents, ban proponents’ claims were grounded in scientific findings, emphasizing menthol’s unique damage to health.61 Ban advocates also returned to industry targeting, as in Phillip Gardiner and Patricia Clark’s statement:

Probably the hallmark of the history of menthol cigarettes is the relentless and unabashed marketing to African Americans, one of the most vulnerable sectors in the United States population.62

Ban proponents such as the American Academy of Pediatrics underscored menthol’s contribution to health disparities, highlighting the “particular disease burden experienced by [the African American] community as a result of menthol cigarettes.”63(p4)

Arguments against banning menthol.

Opponents continued to speculate that banning menthol would produce a black market. The Center for Regulatory Effectiveness claimed a ban would fuel trafficking in “counterfeit cigarettes” more damaging to health than menthol.64 The National Troopers Coalition suggested “significant demand for contraband”65 would overstress law enforcement resources. Industry spokespeople estimated that black market sales of menthol would cost the government “billions of dollars” in tax revenues66 as well as “500,000 American jobs.”67

Industry speakers attacked scientific justifications for banning menthol including whether worsened health outcomes or health disparities were suffered by African American smokers.68 Altria claimed “Research on the effect of menthol cigarette use on smoking cessation outcomes is characterized by null and inconsistent findings,” while “Research on the topic of menthol cigarette use and smoking initiation is limited and constrained by measurement issues.”69(p11) Lorillard even criticized the committee itself:

TPSAC’s methods are neither transparent nor evidence-based. . . . TPSAC’s methods in reaching its conclusions cannot be replicated and many conclusions are not scientifically justified.70(p2)

DISCUSSION

The effort to regulate menthol spawned an acrimonious discussion in news coverage and during the TPSAC’s inaugural hearings. During act news coverage, private health authorities consistently advocated banning menthol though the exemption divided advocates over whether to support the act.71,72 By May 2008, the National African American Tobacco Prevention Network withdrew its support for the bill. Other health groups such as the American Legacy Foundation continued to press for banning menthol while supporting the act, and the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids advocated for the bill and against an immediate ban.

Once the exemption became law, ban advocates’ presence in news coverage shrank. Antiban statements in the news rose during TPSAC deliberations, as did the industry’s presence. During TPSAC hearings, the industry—especially Lorillard—now had the financial incentive to influence the news and the committee proceedings to prevent a menthol ban.

News emphasis on the health community’s argument that menthol discriminated against African Americans, introduced during act negotiations, shifted during TPSAC proceedings to the opponents’ claim that a ban unfairly curtailed African American smokers’ freedom to choose menthol cigarettes. Increasingly, groups with a history of industry ties52,53,56 spoke on behalf of African Americans, and others, such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and most health advocates, either left the debate over disagreement with the exemption, or were no longer quoted in news coverage.62,73 In news coverage, the industry strategically reframed the value of fairness to prevent banning menthol.

Though not as visible in TPSAC news coverage, health advocates were well represented in TPSAC proceedings with arguments for banning menthol, but, in commitment to scientific honesty, also acknowledged limitations in the data. In some instances, they summarized, but did not refute, tobacco industry’s defense of menthol. By contrast, tobacco industry submissions denied any additional harm from menthol without acknowledging contravening findings. The committee also saw opposition from industry allies across business, labor, civil rights, and law enforcement.

In TPSAC testimony, the industry denied harm from mentholated cigarettes. Yet in news coverage, industry representatives used inflammatory language claiming a ban risked benefiting “terrorist organizations” through a potential black market, eliminating jobs, and reversing civil rights gains.

Implications for Public Health

In TPSAC news coverage and in documents submitted to the committee, industry and its allies had a greater presence than did the health community. With health leaders divided over the exemption, the industry increasingly controlled the message that a ban would create a black market and discriminate against the African American community.

These arguments are not mere rhetoric, but materially affect our regulatory bodies. The report on menthol from TPSAC repeated the industry’s argument that “a black market for menthol cigarettes could be created, criminal activity could ensue, and different methods might be used to supply such a black market,”16(p225) which some have suggested may give the FDA an excuse not to ban menthol.74 Given the tobacco industry’s history of manipulating news coverage,75,76 undermining scientific consensus,23,77 and disrupting public health interventions21,22,78 to achieve their self-interested goals, advocates must inform regulatory bodies and the public debate that influences policymakers. The tobacco industry’s tremendous economic resources no doubt affect their ability to be present in these proceedings compared with health practitioners. To neutralize this advantage, funding institutions must invest in the organizations that represent the communities most at risk from public health disparities to elevate these voices in health equity debates.

Conclusions

These findings illustrate the tobacco industry’s tenacious opposition during every policymaking moment, legislative or regulatory.

Our study has several limitations. Our coding criteria likely overestimated the prevalence of mixed documents submitted by private health authorities to TPSAC that provided antiban and proban perspectives in the course of responding to TPSAC’s specific questions, even though the document authors felt a ban was warranted. Outside the TPSAC venue, for instance, the University of California San Francisco scholars commissioned to review internal industry documents articulated how their evidence supported a ban.79–85 By analyzing only the first instance of each argument in TPSAC documents we underestimated the prevalence of the frames used before the committee; we also examined only a subset of TPSAC documents. Future research could reexamine these documents to assess the entire debate. Furthermore, although we examined the public discourse around banning menthol, future work could investigate whether or how funding decisions, power relationships within public health, and other institutional factors can produce inequitable policymaking.86

Discussing race in America is often divisive, as we found in the debate over eliminating menthol. Tobacco industry spokespeople insisted that making menthol available connected them to African Americans’ struggle for justice, and enlisted civil rights groups to help them make that case. Public health groups made the opposite argument that banning menthol was necessary to protect African Americans’ health, but their voices were inconsistent and diminished over time. In future debates, public health must prioritize and invest in the leadership of communities most affected by health harms to ensure a strong and unrelenting voice in support of health equity.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge grant support from the National Cancer Institute (2R01CA087571).

We thank Laura Nixon, MPH, Priscilla Gonzalez, MPH, Maggie Corcoran, and Megan Skillman for their research assistance, and Makani Themba, Philip Gardiner, DrPH, and Lissy C. Friedman, JD, for providing critical feedback on the article.

Human Participant Protection

Human participant protection was not required because this research did not involve human participants.

References

- 1.Tan CE, Kyriss T, Glantz S. Tobacco company efforts to influence the Food and Drug Administration–commissioned Institute of Medicine report clearing the smoke: an analysis of documents released through litigation. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kreslake JM, Wayne GF, Alpert HR, Koh HK, Connolly GN. Tobacco industry control of menthol in cigarettes and targeting of adolescents and young adults. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(9):1685–1692. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.125542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Use of Menthol Cigarettes. 2009. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k9/134/134MentholCigarettes.htm. Accessed October 21, 2013.

- 4.Benowitz NL, Herrera B, Jacob P., III Mentholated cigarette smoking inhibits nicotine metabolism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310(3):1208–1215. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.066902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delnevo CD, Gundersen DA, Hrywna M, Echeverria SE, Steinberg MB. Smoking-cessation prevalence among US smokers of menthol versus non-menthol cigarettes. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4):357–365. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardiner PS. The African Americanization of menthol cigarette use in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(suppl 1):S55–S65. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001649478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ries L, Melbert D, Krapcho MS . SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2005. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tobacco use among US racial/ethnic minority groups—African Americans. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1998. American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: a report of the Surgeon General. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Federal Trade Commission. Cigarette report for 2007 and 2008. 2011. Available at: http://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-cigarette-tobacco-report-2007-and-2008/110729cigarettereport.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2014.

- 10.Hetherington K. FDA could send Lorillard share up in smoke. 2013. Available at: http://seekingalpha.com/article/1798382-fda-could-send-lorillard-shares-up-in-smoke. Accessed November 5, 2013.

- 11. Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. Pub L No. 111-31, 123 Stat 1776 (2009)

- 12.Fritschler A, Rudder C. Smoking and Politics: Bureaucracy Centered Policymaking. 6th ed. New York, NY: Pearson/Prentice Hall; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derthick M. Up in Smoke: From Legislation to Litigation in Tobacco Politics. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: CQ Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson D. Senate approves tight regulation over cigarettes. New York Times. 11, June 2009;sect 1:1. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Action on Smoking and Health. 2009. Help ban lethal menthol loophole. Available at: http://www.ash.org/menthol. Accessed November 5, 2013.

- 16. Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. Menthol Cigarettes and Public Health: Review of the Scientific Evidence and Recommendations. 2011. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM269697.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2013.

- 17. US Food and Drug Administration. Preliminary Scientific Evaluation of the Possible Public Health Effects of Menthol Versus Nonmenthol Cigarettes. 2013. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/PeerReviewofScientificInformationandAssessments/UCM361598.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2013.

- 18. Menthol in cigarettes, tobacco products; request for comments; extension of comment period. Fed Regist. 2013. Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2013/09/11/2013-22015/menthol-in-cigarettes-tobacco-products-request-for-comments-extension-of-comment-period. Accessed October 21, 2013.

- 19.Dorfman L, Cheyne A, Gottlieb M et al. Cigarettes become a dangerous product: tobacco in the rearview mirror, 1952–1965. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):37–46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandt AM. Inventing conflicts of interest: a history of tobacco industry tactics. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):63–71. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glantz SA, Balbach ED. Tobacco War: Inside the California Battles. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Proctor RN. Golden Holocaust: Origins of the Cigarette Catastrophe and the Case for Abolition. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dearing JW, Rogers EM. Agenda-Setting. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCombs M, Reynolds A. How the news shapes our civic agenda. In: Bryant J, Oliver M, editors. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis; 2009. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gamson W. Talking Politics. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Entman RM. Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J Commun. 1993;43(4):51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iyengar S. Is Anyone to Blame? How Television Frames Political Issues. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hilgartner S, Bosk C. The rise and fall of social problems: a public arenas model. Am J Sociol. 1988;94:53–78. [Google Scholar]

- 29.State of the Media Annual Report. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Food and Drug Administration. Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. 2013. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/default.htm. Accessed October 21, 2013.

- 31.Altheide D. Reflections: ethnographic content analysis. Qual Sociol. 1987;10(1):65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krippendorff K. Testing the reliability of content analysis data: what is involved and why. In: Krippendorff K, Bock MA, editors. The Content Analysis Reader. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2008. pp. 350–357. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yerger V, McCandless P. Menthol sensory qualities and possible effects on topography: a white paper. 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM228128.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2013.

- 34.Salgado M. Potential health effects of menthol: a white paper. 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/advisorycommittees/committeesmeetingmaterials/tobaccoproductsscientificadvisorycommittee/ucm228124.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2014.

- 35.Anderson SJ. Menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation behavior: a white paper. 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM228119.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2014.

- 36.Yerger VB. Menthol’s potential effect on nicotine dependence: a white paper. 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM228127.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2014.

- 37.Anderson SJ. Marketing of menthol cigarettes and consumer perceptions: a white paper. 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM228120.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2014.

- 38.Klausner K. Menthol cigarettes and the initiation of smoking: a white paper. 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM228121.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2014.

- 39.Beckwith L. TPSAC report and recommendation on menthol cigarettes. 2011. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM262378.pdf. Accessed December 27, 2013.

- 40.Redhead CS, Garvey T. FDA final rule restricting the sale and distribution of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco. 2010. Available at: http://www.nacsonline.com/Issues/Tobacco/Documents/CRSReport.pdf. Accessed November 6, 2013.

- 41.Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. 2010 TPSAC meeting materials and information. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/ucm180903.htm. Accessed November 6, 2013.

- 42.Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. October 7. 2010: Meeting of the Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/ucm226455.htm. Accessed November 6, 2013.

- 43.Young A. Tobacco-regulation bills: menthol not on banned list. Atlanta Journal-Constitution. May 29, 2008;sect A:1. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones T. Blacks seen as targets of menthol; exemption for additive troubles many critics. Chicago Tribune. August 13, 2008;sect C:1. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCullough M. Senate bill gives FDA power over tobacco. Philadelphia Inquirer. June 12, 2009;sect A:1. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Orlowsky ML. Menthol cigarettes. 2008. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/10/opinion/lweb10tobacco.html. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- 47.Saul S. Bill to regulate tobacco as a drug is approved by a House committee. New York Times. April 3, 2008;sect 3:3. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Innis N. When good intentions have disastrous effects. Philadelphia Tribune. December 14, 2010;sect A:11. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saul S. Opposition to menthol cigarettes grows. New York Times. July 17, 2008;sect C:1. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smalera P. Cool, refreshing legislation for Philip Morris. 2009. Available at: http://www.theroot.com/articles/politics/2009/06/why_its_politically_impossible_to_ban_menthol_cigarettes.html. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- 51.Wooten J. Thinking right; CRCT, menthol, a “bloody fortune.” Atlanta Journal-Constitution. 2008. Available at: http://www.ajc.com/opinion/content/shared-blogs/ajc/thinkingright/entries/2008/05/30/crct_menthol_a_bloody_fortune.html. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- 52.Yerger VB, Malone RE. African American leadership groups: smoking with the enemy. Tob Control. 2002;11(4):336–345. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.4.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yerger VB. 2011. Who’s still smoking with the enemy? Available at: http://sh.exdep.com/presentations/177492/index.html. Accessed April 17, 2014.

- 54.Board E. Tobacco regulation: kneecapping the FDA. Los Angeles Times. June 5, 2011;sect A:27. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rubin R. 2011. FDA weighs ban on Newports, other menthol cigarettes. Available at: http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/health/story/health/story/2011/03/FDA-weighs-ban-on–Newports-other-menthol-cigarettes/44877538/1. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- 56.McGruder CO. Big pimping: Big Tobacco is at it again! 2011. Available at: http://sfbayview.com/2011/big-pimping. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- 57.Glanton D. Blacks divided over possible FDA ban of menthol cigarettes. Washington Post. January 2, 2011;sect C:1. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aziz M. Banning menthol cigarettes: the disproportionate effects and the illegal underground market. 2011. Available at: http://www.blacknews.com/news/banning_menthol_cigarettes_illegal_market101.shtml. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- 59.Lee J. Banning menthol cigarettes will create a huge illegal, contraband market. 2010. Available at: http://www.blacknews.com/news/jessie_lee_banning_menthol_cigarettes101.shtml. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- 60.McNichol T. Mint that kills: the curious life of menthol cigarettes. 2011. Available at: http://www.theatlantic.com/life/print/2011/03/mint-that-kills-the-curious-life-of-menthol-cigarettes/73016. Accessed October 28, 2013.

- 61.Hawkins DJ. Eliminating menthol from tobacco. 2011. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM218791.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- 62.Gardiner PS, Clark PI. The harm associated with menthol cigarettes. 2010. Available at: http://www.capitolconnection.net/capcon/fda/fda033010_launch.htm. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- 63.Winickoff JP. Statement before the Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM238828.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2013.

- 64.Center for Regulatory Effectiveness. The countervailing effects of counterfeit cigarettes. 2011. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM263564.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- 65.Hallion D. National Troopers Coalition statement to Caryn Cohen on banning menthol. 2010. Available at. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM246013.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- 66.Carlton DW, Flyer F. 2011. Estimating consequences of a ban on the legal sale of menthol cigarettes. Available at. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM240170.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- 67.Dillard JE. Countervailing effects of a ban on menthol cigarettes. 2010. Available at. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM246043.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- 68.Lorillard Tobacco Company. Briefing regarding the science relating to menthol cigarettes. 2010. Available at. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM218781.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- 69.Dillard JE. Re: March 30–31, 2010 meeting of the Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM218767.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- 70.Lorillard Tobacco Company. Lorillard’s comments to FDA on the TPSAC report on menthol cigarettes. 2011. Available at: http://www.lorillard.com/pdf/fda/Comments_to_FDA_on_TPSAC_Report.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- 71.Healy M. Much heated puffing among minority groups over menthol cigarette ban. Los Angeles Times. 2010. Available at: http://articles.latimes.com/2010/oct/18/news/la-heb-menthol-101810. Accessed November 18, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moffett F. Restrictions sought on menthol cigarettes. The Chicago Defender. 2008;103(11):8. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gardiner PS. Re: January 10 the Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC) public comment written material on banning menthol in cigarettes. 2010. Available at. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM246048.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- 74.Siegel M. A lost opportunity for public health—the FDA advisory committee report on menthol. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(23):2177–2179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1103403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Swisher CK, Reese SD. The smoking and health issue in newspapers: influence of regional economies, the Tobacco Institute and news objectivity. Journalism Mass Commun Q. 1992;69(4):987–1000. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Menashe CL. The power of a frame: an analysis of newspaper coverage of tobacco issues—United States, 1985–1996. J Health Commun. 1998;3(4):307–325. doi: 10.1080/108107398127139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yach D, Bialous SA. Junking science to promote tobacco. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(11):1745–1748. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Proctor RN. “Everyone knew but no one had proof”: tobacco industry use of medical history expertise in US courts, 1990–2002. Tob Control. 2006;15(suppl 4):iv117–iv125. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Salgado M, Glantz SA. Direct disease-inducing effects of menthol through the eyes of tobacco companies. Tob Control. 2011;20(suppl 2):ii44–ii48. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.041962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee YO, Glantz SA. Menthol: putting the pieces together. Tob Control. 2011;20(suppl 2):ii1–ii7. doi: 10.1136/tc.2011.043604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Anderson SJ. Marketing of menthol cigarettes and consumer perceptions: a review of tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2011;20(suppl 2):ii20–ii28. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.041939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Klausner K. Menthol cigarettes and smoking initiation: a tobacco industry perspective. Tob Control. 2011;20(suppl 2):ii12–ii19. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.041954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yerger VB. Menthol’s potential effects on nicotine dependence: a tobacco industry perspective. Tob Control. 2011;20(suppl 2):ii29–ii36. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.041970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yerger VB, McCandless PM. Menthol sensory qualities and smoking topography: a review of tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2011;20(suppl 2):ii37–ii43. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.041988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Anderson SJ. Menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation behaviour: a review of tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2011;20(suppl 2):ii49–ii56. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.041947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Goldfield M. The Color of Politics: Race and the Mainsprings of American Politics. New York, NY: New Press;; 1997. [Google Scholar]