Abstract

Public opinion polarization is here conceived as a process of alignment along multiple lines of potential disagreement and measured as growing constraint in individuals’ preferences. Using NES data from 1972 to 2004, the authors model trends in issue partisanship—the correlation of issue attitudes with party identification—and issue alignment—the correlation between pairs of issues—and find a substantive increase in issue partisanship, but little evidence of issue alignment. The findings suggest that opinion changes correspond more to a resorting of party labels among voters than to greater constraint on issue attitudes: since parties are more polarized, they are now better at sorting individuals along ideological lines. Levels of constraint vary across population subgroups: strong partisans and wealthier and politically sophisticated voters have grown more coherent in their beliefs. The authors discuss the consequences of partisan realignment and group sorting on the political process and potential deviations from the classic pluralistic account of American politics.

INTRODUCTION

According to theorists of political pluralism (Truman 1951; Dahl 1961; Lowi 1969; Walker 1991; see also Galston 2002; Starr 2007) as well as many scholars who have studied the structural characteristics of contemporary societies (Simmel [1908] 1955; Coser 1956; Lipset, Trow, and Coleman 1956; Lipset 1963; Lipset and Rokkan 1967; Blau 1974; Blau and Schwartz 1984), an integrated society is not a society in which conflict is absent, but rather one in which conflict expresses itself through non-encompassing interests and identities. In open societies, “segmental participation in a multiplicity of conflicts constitutes a balancing mechanism within the structure” (Coser 1956, p. 154): intrasocial conflict is sustainable as long as there are multiple and nonoverlapping lines of disagreement.

In the attempt to propose a pragmatic alternative to both the ideal of direct, popular democracy and the belief that American politics is governed by a small, unitary power elite (Mills [1956] 1970; Domhoff 1978), pluralism scholars recognize that, in practice, representative democracies do not support the ideal of equal representation. Nonetheless, these scholars maintain that a multitude of interest groups, not a close circle, have access to power. Intergroup competition, as well as institutional differentiation, limits the influence of single actors, thus securing the openness of the democratic process.2 At the same time, crosscutting interests inhibit the emergence of encompassing identities, because members’ allegiance is often spread among many groups, thus diminishing the possibility of overt conflict.

Political polarization constitutes a threat to the extent that it induces alignment along multiple lines of potential conflict and organizes individuals and groups around exclusive identities, thus crystallizing interests into opposite factions. In this perspective, opinion alignment, rather than opinion radicalization, is the aspect of polarization that is more likely to have consequences on social integration and political stability. From a substantive viewpoint, if people aligned along multiple, potentially divisive issues, even if they did not take extreme positions on each of them, the end result would be a polarized society. Analytically, it can be shown that people's ideological distance and, thus, polarization depend not only on the level of radicalization of their opinions but also on the extent to which such opinions are correlated with each other—their constraint, in the language of Converse (1964). Nonetheless, the study of public opinion polarization has been mostly oriented to capture the radicalization of people's attitudes on single issues (looking at the variation of responses on an individual issue in the population, where more variation corresponds to more people on the extremes and fewer in the middle), while questions concerning the coherence of people's opinions across issues have generally been overlooked. In contrast, in this article we focus on the level of attitude constraint and trace time trends in issue partisanship and issue alignment in the population as a whole and within population subgroups.

According to the political pluralism model, democratic systems are characterized by crosscutting interests and identities and actual (if not equal) access to political representation for most (if not all) social groups. Results from our analysis will be used to evaluate potential deviations from this model due to alignments of interests that might sharpen divisions in the political arena and group or partisan sorting that might lead to the systematic underrepresentation (or even exclusion) of certain groups (and related interests) from the political process.3 In so doing, we connect the debate on political polarization to broader dynamics of interest representation and political integration.

There is virtually full agreement among scholars that political parties and politicians, in recent decades, have become more ideological and more likely to take extreme positions on a broad set of political issues (McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal 2006). Though many observers have concluded that a similar polarization process has extended to public opinion at large, scholars have shown that, over the last 40 years, American public opinion has remained stable or even become more moderate on a large set of political issues, while people have assumed more extreme positions only on some specific, hot issues, such as abortion, sexual morality, and, lately, the war in Iraq (DiMaggio, Evans, and Bryson 1996; Evans 2003; Fiorina, Abrams, and Pope 2005; Shapiro and Bloch-Elkon 2006). More systematic polarization appears in mass partisanship: those who are politically active or identify themselves with a party or ideology tend to have more extreme positions than the rest of the population. Moreover, the relation between party identification (or liberal-conservative political ideology) and voting behavior has reached its highest level in the last 50 years, after the era of partisan dealignment of the 1960s and 1970s (Bartels 2000; Hetherington 2001; Bafumi 2004).

For those scholars according to whom political polarization must imply a divergence of public opinion on a broad set of issues (DiMaggio et al. 1996) and reflect a consistent set of alternative beliefs (Fiorina et al. 2005), American public opinion is not polarized: there is evidence of attitude polarization only on a few issues, and people are often ambivalent in their preferences. Conversely, for those scholars who think that polarization is in place when broad ideological or partisan dividing lines exist, even though public opinion polarizes only on certain issues, American public opinion is polarized (Kohut et al. 2000; Green, Palmquist, and Schickler 2002; Greenberg 2004; Mayer 2004; Abramowitz and Saunders 2005; Bafumi and Shapiro 2007).

With respect to the increased partisanship of the general public, two different explanations can be advanced. One hypothesis is that citizens are changing, becoming more coherent in their political preferences over time; the other is that, even though their preferences have remained stable, citizens have responded to the growing party extremism by splitting into alternative camps.

The substantive contribution of our analysis is to offer support for the latter hypothesis by showing that Americans have become more coherent in matching their issue preferences with their party and ideology, but their level of issue constraint has remained essentially stable—and low. Thus, increased issue partisanship is not due to higher ideological coherence; rather, as suggested by Fiorina et al. (2005), it mostly arose from parties’ being more polarized and therefore doing a better job at sorting individuals along ideological lines. Individuals themselves have not moved; simply, they now perceive parties as being more radical, and they split accordingly. However, party polarization might have gained momentum as party voters became more clearly divided in their preferences, thus establishing a self-reinforcing dynamic.

Outline

The article unfolds as follows: First, we summarize the current debate on elite and public opinion polarization and outline our hypotheses about the trends in issue partisanship and issue alignment. Second, we claim that the coherence of individuals’ beliefs systems is relevant when discussing polarization, and we support our argument by using a simple theoretical model to show that variations in the level of correlation of political preferences induce variations in the overall ideological distance between individuals.

We next present our method and data. We use the American National Election Study (NES) cumulative data set (1972–2004) to study trends in issue partisanship (bivariate correlations of issues with party identification or ideology) and issue alignment (correlations between pairs of issues).4

We report results in three sections. The first section focuses on issue partisanship and suggests that citizens’ opinions on some issues—especially, but not exclusively, moral issues—have become substantially more correlated with party identity and political ideology over time. In the second section, we turn to issue alignment and show that there is no comparable increase in the correlation between issues. Moreover, we do not observe increasing correlation between issue domains, and we therefore conclude that there is no evidence of issue alignment in the mass public. In the third section, we look at trends in issue partisanship and issue alignment within population subgroups. This allows us to conclude that political activists, southerners, and churchgoers have experienced patterns of issue partisanship and alignment similar to those observed in the rest of the population. In contrast, politically sophisticated and wealth-ier voters have seen faster growth in issue partisanship and alignment. Finally, patterns of issue alignment differ somewhat between Republican and Democratic voters. In the discussion, we focus on the consequences of these opinion changes on the political process, inviting a reconsideration of the traditional liberal-pluralistic account of American politics.

THE DEBATE OVER POLITICAL POLARIZATION

Political polarization is not new in American politics. According to Brady and Han's (2006, p. 120) historical analysis, “For many years, our political institutions and policy-making processes have withstood sharp divisions between the parties”; this includes the Civil War era, the turn of the 20th century, and the New Deal era. What is distinctive about the present period is the division between elite and mass polarization. There is in fact ample evidence of polarization in the party-in-government and the party-as-organization—to use the classical categories of V. O. Key (1958)—but a veil of ambiguity remains (despite a decade of research) with respect to the party in the electorate.5

Party and Activist Polarization

After a long period of depolarization that began at the end of World War I, political parties started to move further apart in the early 1970s. As documented by the extensive analysis of congressional roll-call voting (Poole and Rosenthal 1984, 2007; Rohde 1991; Aldrich 1996), interest groups’ ratings (Poole and Rosenthal 2007, chap. 8), and other sources (Layman, Carsey, and Horowitz 2006), members of Congress have aligned at opposite ends of the liberal–conservative spectrum, and the number of moderate representatives has steadily decreased.

The electoral realignment of the southern states (Carmines and Stimson 1989; Rohde 1991; Layman et al. 2006; Ansolabehere and Snyder 2008) and the mobilization, in the middle of the 1960s, of grassroots conservative groups during the Goldwater campaign (Perlstein 2001; Brady and Han 2006) marked the beginning of a consistent movement of the Republican Party toward more conservative positions. Exiting moderate Republican members of Congress were replaced by a new cohort of socially conservative Republicans. This trend became even more prominent in the early 1990s. Simultaneously, moderate Democrats retired or were defeated, and new Democratic members were more liberal, and so the divisions between northern and southern Democrats in Congress were diminished (Wilcox 1995; Fleisher and Bond 2000; Jacobson 2005). The political issues at stake in this period well reflected the declining bipartisanship of the national elite, from Ronald Reagan's economic and social program, to the socially conservative program and confrontational strategy that characterized the Republican Party in the early 1990s, to Bill Clinton's liberal policies on matters of gay rights, abortion, taxation, and health insurance (Trubowitz and Mellow 2005).

Several scholars have identified the increased polarization of party activists as the element that has triggered party polarization. Indeed, activists have become more important in the selection of party nominees in recent decades, and they tend to have more radical views than the average citizen. In addition, the growth, starting in the 1970s, of single-issue-based interest groups has had a radicalizing effect on parties’ primaries and legislative behavior in Congress (Saunders and Abramowitz 2004; Brady and Han 2006; Layman et al. 2006). Polarization shows similar trends among activists as among congressional representatives, although a clear causal relation has yet to be established. Nonetheless, once activated, party and activist polarization dynamics might have reinforced each other: the more party leaders “emphasize ideological appeals, the more likely that party will be to attract ideologically motivated activists. The involvement of these ideologically motivated activists may, in turn, reinforce ideological extremism among party leaders” (Saunders and Abramowitz 2004, p. 287). Both mechanisms of persuasion and mechanisms of selective recruitment were at work in radicalizing leaders (Fleisher and Bond 2000) and activists (Layman and Carsey 2002), with the final outcome of making the core of the Democratic Party more liberal and its Republican counterpart more conservative.

It does not come as a surprise, therefore, that after a period of decline in the importance of party identification and ideology, partisan loyalties have started to count more, to the point that, in the middle of the 1990s, their impact on voting behavior reached its highest level in at least 50 years (Abramowitz and Saunders 1998; Bartels 2000; Hetherington 2001; Bafumi 2004). Nonetheless, the fact that self-identified Republicans (or conservatives) are more likely to vote for the Republican Party today than they were 30 years ago—and the same is true of Democrats—should not be interpreted per se as a sign of public opinion polarization. Rather, “Elite polarization has clarified public perceptions of the parties’ ideological differences” (Hetherington 2001, p. 619), and therefore “the public may increasingly come to develop and apply partisan predispositions” (Bartels 2000, p. 44). To what extent increased mass partisanship has brought about (or is related to) public opinion polarization—and to what extent individuals’ partisanship conforms with their issue preferences—is still an open question.

Public Opinion Polarization

The debate among scholars on the level of polarization of the American public has grown along with a certain ambiguity on what opinion polarization really means and how it should be empirically measured. One way to look at public opinion polarization is to focus on the distribution of political attitudes across all Americans. If there is polarization, we should observe a change in the shape of the opinion distribution, moving from a unimodal to a flat or bimodal distribution. DiMaggio et al. (1996), looking at the population as a whole, have documented a general trend toward consensus on racial, gender, and crime issues, stability on numerous others, and evidence of polarization only on attitudes toward abortion, the poor, and, more recently, sexual morality (Evans 2003).

But one might want to track changes between subgroups of the population, distinguishing people along sociodemographic lines. For this purpose, DiMaggio et al. (1996) looked at the level of opinion disagreement between subgroups by comparing different categories of respondents. The results suggest that evidence of intergroup polarization is scarce. With respect to age, gender, education, region, and religious affiliation, the results portray stability or even instances of depolarization. Fiorina et al. (2005) and Fischer and Hout (2006) reach more or less the same conclusions. In contrast, Abramowitz and Saunders (2005) suggest that the mass public is deeply divided between red states and blue states and between churchgoers and secular voters.

Alternatively, one can look for changes in the distance between partisan subgroups, distinguishing people along ideological lines. In this case, there is clear evidence of polarization between self-identified liberals and conservatives, as well as among party affiliates and political activists (DiMaggio et al. 1996; Abramowitz and Saunders 2005; Fiorina et al. 2005). Bafumi and Shapiro (2007), analyzing the trend in the mean position of Democrats and Republicans and liberals and conservatives with respect to a large set of political issues, have found that partisans and ideologues are increasingly divided not only on issues such as abortion, gay rights, and the role of religion, but also on issues of race and civil rights. Similarly, Layman and Carsey (2002) have found that attitude constraint between social welfare and moral issues has increased among party identifiers (i.e., people who identify with a political party). Finally, looking at party voters, the divide between Democrats and Republicans has greatly increased on many issues (Jacobson 2005, 2007).

In general, scholars’ analyses differ because of the social or partisan categories (class, ethnicity, religious affiliation, party identification, etc.) that are thought to be relevant for mapping social division and the dimensions around which public opinion is expected to split (polarization might be confined to people's attitudes on specific issues or instead spread across a broad set of issues). The way in which these two aspects have been combined has led different scholars to different conclusions.

When the focus is on the population as a whole or on different social groups (thus slicing the population along socioeconomic lines), scholars find evidence of polarization only on a few political attitudes. This has led them to conclude that, in general, American citizens are uncertain and ambivalent and therefore more likely to take central positions than extreme positions and to combine conservative and liberal attitudes on different issues. The same scholars have also tended to look at polarization across multiple issue domains, thus emphasizing the overall stability of public opinion. In contrast, scholars who look primarily at partisan affiliations and thus slice the population along party or ideological lines have concluded that the nation is increasingly divided. They also tend to give disproportionate attention to currently salient issues such as abortion or the war in Iraq. These scenarios do not necessarily contradict each other (Baldassarri and Bearman 2007). Indeed, both are realistic—although not complete—descriptions of contemporary America.

In this article we provide a comprehensive account of trends in issue partisanship (the relation between issues and ideology) and issue alignment (the level of constraint within and between diverse issue domains), thus disentangling the effect of party ideology from dynamics of alignment in attitude preferences. Increased issue partisanship can be thought of as a reflection of parties’ differentiation and elite polarization, whereas higher levels of issue alignment would suggest that citizens are increasingly splitting along multiple lines of potential conflict. While both dynamics might have consequences on political integration—an aspect that we will discuss in the conclusion of this article—issue alignment is more likely to amplify the ideological distance between citizens and thus increase public opinion polarization, while issue partisanship might foster dynamics of unequal representation.

By separately investigating the extent to which the electorate has become more ideological and actual changes in the way in which people (or some population subgroups) combine their issue preferences, we can properly address the two most popular explanations of the changes in American public opinion. One explanation argues that elite polarization has made it easier for ordinary citizens to see the differences between parties and that therefore citizens are now better at sorting themselves between Republicans and Democrats or liberals and conservatives (Hetherington 2001; Fiorina et al. 2005; Levendusky 2004). The other argues that citizens (or subgroups of them) have themselves changed and that moral issues have lined up with economic and civil rights issues to substantially radicalize people's preferences and boost their partisanship (Layman and Carsey 2002; Abramowitz and Saunders 2005; Bafumi and Shapiro 2007). Two hypotheses follow:

Hypothesis 1.—If it is parties that are moving, while people's opinions have not changed, we expect to observe increasing issue partisanship (evidence that parties are better at sorting out their voters) but no increase in constraint in people's political attitudes—and thus no issue alignment.

Hypothesis 2a.—If a real movement has occurred within the population, we expect instances of issue alignment in public opinion and thus higher levels of constraint among issues and between issue domains.

In general, growing levels of alignment of interests might challenge the political pluralist model of crosscutting interests, but this might occur solely among the political elite (hypothesis 1) or among the larger public as well (hypothesis 2a). A second potential deviation from the political pluralism model is introduced by dynamics of group or partisan sorting, leading to the systematic underrepresentation of certain social categories. We study this second aspect by analyzing time trends within population subgroups and consider some possible variants of hypothesis 2a.

In the literature on public opinion, the theme of issue consistency and constraint has been investigated for a long time, usually with the conclusion that only a minority of very interested and informed people show real opinion constraint, while the large majority of the public is “innocent of ideology” (Converse 1964, p. 241). In the last two decades, the debate has been reframed in terms of population heterogeneity, and scholars have focused on the different heuristics people deploy in their political reasoning (Sniderman, Brody, and Tetlock 1991; Lupia, McCubbins, and Popkin 2000; Baldassarri and Schadee 2006). In both cases, results suggest that there are substantial differences across citizens with respect to their level of political sophistication and that only a small group of them fully deploy ideological categories. Since politically sophisticated and active citizens are more likely to be politically influential (Katz and Lazarsfeld 1955) but also have more extreme political views (Baldassarri 2008), it is relevant to investigate whether trends in issue partisanship and alignment among the subset of politically committed citizens differ from trends in the entire population. In fact, an influential minority can affect, in the long term, the political preferences of the rest of the electorate (Layman and Carsey 2002). We therefore consider the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2b.—A real movement has occurred within the subset of the population that is politically more sophisticated or active.

Within a broad set of social categories (gender, age, ethnicity, class, geographic location, etc.) some social groups are, or have the potential to become, politically influential (through lobbying and interest groups) and thus have an impact on the policy-making process—for instance, by setting the agenda. If instances of polarization occur within such groups, this might reverberate with the political elite, if not with the mass public. Present-day lines of potential social division seem to be based on economic status—often measured through education or income (Frank 2004; Ansolabehere, Rodden, and Snyder 2006b; Bartels 2006; Fischer and Hout 2006; McCarty et al. 2006;)—and cultural values, captured here by region and religion (Abramowitz and Saunders 2005; McVeigh and Soboleski 2007). We therefore study the differences between trends in partisanship and issue alignment for different population subgroups.

Hypothesis 2c.—A real movement has occurred within some population subgroups (such as more educated and wealthier people, southerners, or churchgoers).

Many studies have documented the increased ideological consistency of party voters (e.g., Abramowitz and Saunders 1998) as well as the growing division between Republicans and Democrats on a broad range of political issues (Bafumi and Shapiro 2007; Jacobson 2007). The sorting of Republicans and Democrats along ideological lines might have translated into greater issue alignment among partisans (Layman and Carsey 2002). Given that the political elite has a vital interest in maintaining its constituency, the consolidation of voters’ preferences might have an impact on parties’ conduct, even if similar patterns are not visible in the population at large. This leads us to our final variation on hypothesis 2a:

Hypothesis 2d.—Issue alignment has occurred among party identifiers.

Correlation as Polarization

The pundits like to slice-and-dice our country into red states and blue states: red states for Republicans, blue states for Democrats. But I've got news for them, too. We worship an awesome God in the blue states, and we don't like federal agents poking around in our libraries in the red states. We coach Little League in the blue states and, yes, we've got some gay friends in the red states. There are patriots who opposed the war in Iraq, and patriots who supported the war in Iraq. (Barack Obama, Democratic National Convention, July 27, 2004)

The fans and the detractors of Senator Barack Obama's celebrated keynote address at the 2004 Democratic National Convention interpreted his lines as a plea for bipartisan politics and national unity. Nonetheless, few observers took it at face value, as an actual picture of the state of the country. This is unfortunate because, in this regard, he got it right.

For instance, in 2004, 40% of the respondents to the NES were self-declared Republicans (including leaners), but only 23% were both self-declared Republicans and conservative (32% if we consider only the subsample of people who answered both questions). Almost half of the Republicans did not perceive themselves as being ideologically conservative. If we also consider issue preferences, the constraint of people's political preferences looks even weaker. Only 12% of the respondents are Republican and conservative and oppose abortion (in part or completely), while 16% are Republican and conservative and do not favor affirmative action, and 13% are Republican and conservative and think that government should not support health insurance programs. Altogether, in our 2004 sample, only 6% of respondents are Republicans who think of themselves as conservatives, oppose abortion, and have conservative views on affirmative action and health policy. Fully 85% of self-declared Republicans are nonconservative or take a nonconservative stand on at least one of these three traditional issues. A similar picture emerges if we look at Democrats. In this case, of the 49% of the sample who are self-declared Democrats, only 36% call themselves liberals. Overall, almost 90% of Democrats are nonliberal or have nonliberal views on abortion, affirmative action, or health policy.

As we have noted above, empirical attempts at assessing the polarization of mass opinion have mostly focused on the distribution of single issues, while rarely looking at the correlation of people's opinions on different political issues. From a substantive point of view, it makes sense that if people align along multiple, potentially divisive issues, even if they do not take extreme positions on single issues, the end result is a polarized society. For instance, consider a population with opinions on two dimensions: color (50% of the people prefer green, 50% prefer yellow) and shape (50% prefer circle, 50% prefer triangle). If opinions are independent (thus, dimensions are orthogonal), 25% of people will prefer green circle, 25% green triangle, 25% yellow circle, and 25% yellow triangle. At the other extreme, if the two dimensions are perfectly correlated, 50% of the people will have one preference (e.g., green circle) and 50% will be in the opposite corner (yellow triangle), but the opinion distribution on the single issues will not change.

For another example, consider a population with opinions on four dimensions, following a multivariate normal distribution with mean 0 and variance 1 on each opinion and correlation r between any pair of issues. In one limiting case, the correlation between dimensions is null and the four opinions are independent; in the other limiting case, the four dimensions have correlation 1, which means that individuals hold exactly the same opinion on all four issues. In between, there are situations in which the four dimensions are correlated, with correlations of different magnitude. As the correlation between issues increases, the opinion distribution on each issue remains the same, but the ideological distance in the population increases.

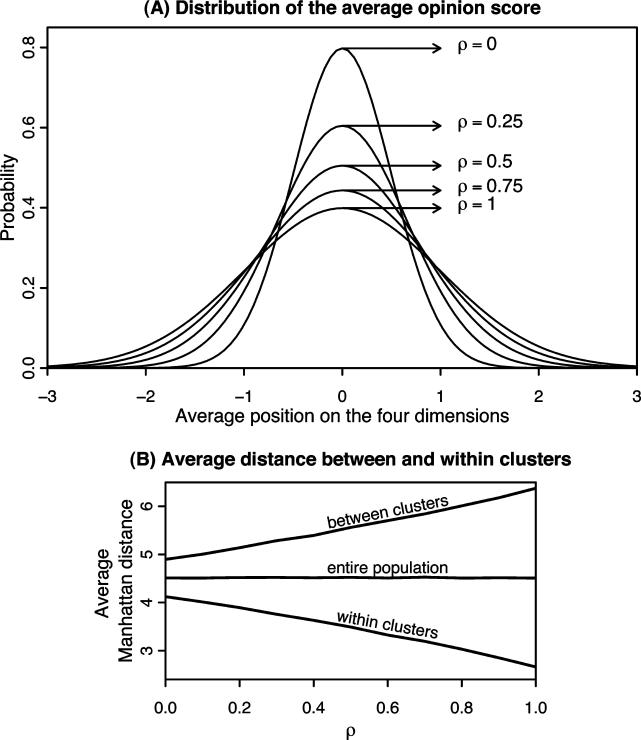

To show this, we measure ideological distance in two ways. First, we compute a synthetic opinion score as the average position on the four dimensions. Figure 1, part A, plots the distribution of the average positions for five different correlations: 0, .25, .5, .75, and 1. As the correlation increases, the variance of the average score distribution grows as well. When dimensions are positively correlated, there are more people with overall extreme views than in a context in which dimensions are not correlated, even though the opinion distribution on each single issue remains the same.

Fig. 1.

Ideological distance for different levels of correlation (ρ) between dimensions, from a simple four-dimensional normal model.

Second, we can measure polarization by returning to the concept presented at the beginning of the article of society's dividing into two homogeneous parts that are far apart from each other, and by therefore focusing on the distribution of distances between pairs of people. The more a population is polarized, the higher the variation of the distance between pairs of individuals, because they are either very close or very distant. According to our argument, we would expect that as the correlation between ideological dimensions increases, the distance between individuals that belong to the same cluster decreases, while the distance between people that belong to alternative clusters increases. Mathematically, we can divide a multivariate distribution into two pieces by finding the optimal separation that will minimize the average distances between people within each piece.6 Here, the population is partitioned into clusters according to the sign of the opinion score previously computed. Figure 1, part B, presents results using Manhattan distance (similar results were obtained using Euclidean distance). In our four-dimensional normal example, where the separate distributions on each issue remain unchanged, we find that, as correlations between issues increase, the average distance between pairs of people remains stable, the average distance between pairs of people within clusters decreases, and the average distance between pairs of people in different clusters increases.

For all these theoretical reasons, we see correlation as an important aspect of polarization that has not been captured in previous analyses of a single question at a time (or in previous analyses such as Ansolabehere, Rodden, and Snyder [2006a], which combine questions in valuable ways to get more useful and precise summaries of issue positions, but do not consider the correlations as informative in themselves). We next turn to the analysis of the correlation between political attitudes in America.

METHODOLOGY AND DATA

High-quality national surveys since the 1970s have included a consistent number of attitude questions on political issues, ranging from state intervention and spending to civil rights, morality, and foreign policy. Unfortunately, few of these questions were asked consistently over time, and so any attempt at tracing the temporal evolution of public opinion on political attitudes is a difficult enterprise. For instance, in what is probably the most comprehensive study of trends in public opinion polarization, DiMaggio et al. (1996) could rely only on seven attitude questions from the NES cumulative data set (of which four were feeling thermometers) and nine attitude questions from the GSS cumulative data set (see also Layman and Carsey 2002; Fischer and Hout 2006).

We overcome the problem that questions were not asked consistently over time and make virtually complete use of the information on respondents’ political attitudes collected through sample surveys. In short, we work with the correlations rather than modeling the data directly.7 We focus on the evolution of the correlation between opinions rather than on the evolution of opinion distributions on single issues. In this way, even though each pair of questions has not been asked for the entire time period, their correlation remains informative to an assessment of the trend in opinion correlations. Specifically, to study the evolution of issue partisanship, we look at the correlation between single issues and party identification or political ideology, while to study trends in issue alignment we focus on the correlation between pairs of issues. Our unit of analysis is issue correlation × year (for issue partisanship) or issue-pair correlation × year (for issue alignment), and the basic idea is that every attitude question that has been asked at least twice can be potentially informative to an assessment of the overall trends in issue partisanship and issue alignment.

Our primary interest lies in time trends of correlation. In any given year, the available data sample is large but not huge, and thus correlation estimates and their trends can be unstable, especially for questions that were asked only for a few years. The simple way to handle this problem is to estimate a common time trend for all the correlations in the study. However, this would not allow us to differentiate between issues and to tell if some are becoming more correlated while others remain stable or show patterns of decreasing correlation. Multilevel models—in this case, varying-intercept, varying-slope models—allow us to estimate variation and trends in the presence of uncertainty in the correlation estimates (Snijders and Bosker 1999; Raudenbush and Bryk 2002; Gelman and Hill 2007).8

Here, we present results from the NES, cumulative data file 1948–2004.9 Questions coded in a comparable fashion across years are merged in this data set. Considering all the attitude questions that were asked at least three times, we analyzed a total of 47 issues. Since most of them were asked beginning in 1972, we present results for the time period 1972–2004.10 To facilitate the interpretation of the results, all questions were coded in order to range opinions on a scale from liberal to conservative, and thus correlations are generally positive.

We classified attitude questions according to four different issue domains: economic, civil rights, moral, and security and foreign policy.11 Examples of economic issues are government's involvement in the provision of health insurance and a jobs guarantee, or federal spending for the poor, welfare, or food stamps. Civil rights issues concern the treatment of African-Americans and other minorities, as well as affirmative action and equality of opportunities and chances, while moral issues range from abortion to gay rights, women's role in society, traditional values, and new lifestyles. Finally, security and foreign policy issues (hereafter referred to as simply foreign policy issues) include, among others, international cooperation, federal spending for defense and crime prevention, and how to handle urban unrest.

In addition to these questions, we measured party identification using the standard seven-point self-identification scale, ranging from strong Democrat (1) to strong Republican (7), and measured political ideology with a seven-point scale that ranges from extremely liberal (1) to extremely conservative (7). We also considered classic sociodemographic variables to study the trend in partisanship and alignment within population subgroups.

RESULTS

Analysis 1: Issue Partisanship

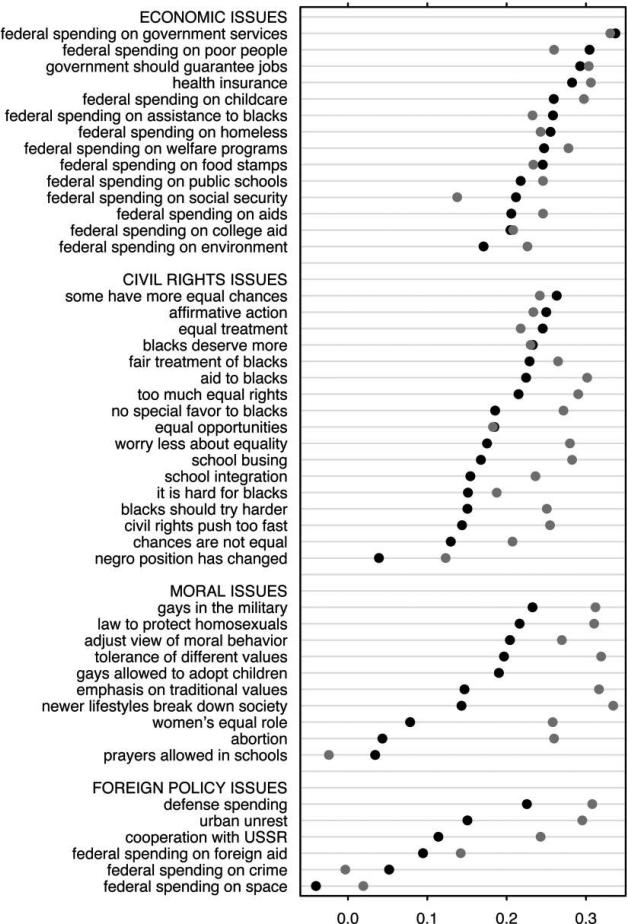

To what extent does party identification or liberal-conservative political ideology predict individuals’ opinions on specific issues? As previously anticipated, the constraint between partisanship and issue attitudes is generally weak. Average correlations between party identification or ideology and issue opinions range between 0 and .3. Figure 2 reports the average correlation between each of the 47 issues and both party identification (black dots) and political ideology (gray dots). Issues are divided among the four domains, and within each domain, they are sorted according to the intensity of the correlation with party identification.

Fig. 2.

Average correlations of issue attitudes with party identification (black dots) and liberal-conservative political ideology (gray dots), by issue domain. For each domain, issues are listed in decreasing order of correlation with party identification. Questions have been coded in order to range opinions from liberal to conservative, so that expected correlations are all positive.

Economic issues have the highest average correlation with party identification, followed by civil rights issues. In contrast, foreign policy issues are loosely related to party affiliation, which confirms their bipartisan nature. Results are similar if we look at the correlation between issues and self-placement on the liberal-conservative continuum, with one interesting exception: moral issues are substantially more linked to ideology than to party identification. The magnitude of the correlation between moral issues and political ideology is similar to that observed for economic issues.

Let us now consider the variation over time. To test the hypothesis of increasing issue partisanship, we fit a multilevel model with varying intercepts and slopes in which the unit of analysis is issue pair × year and the second-level units are issues. This model allows the average correlation (intercept) and time trend (slope) to vary by issue. Formally,

| (1) |

where ρit is the correlation between issue i and the measure of partisanship in the year t (i ranges from 1 to 47, while t is time in decades).12 Table 1 displays the results for this model, fit separately to correlations of issue attitudes with party identification (col. A) and with political ideology (col. B).

TABLE 1.

Correlation Results from Multilevel Models for Issue Partisanship

| ρ ≡ Issue × Party ID | ρ ≡ Issue × Ideology | |

|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | |

| Intercept . . . . . . . . . . . | .17 (.01) | .22 (.01) |

| Time (decades) . . . . | .05 (.01) | .04 (.01) |

| Residual SD: | ||

| Intercepts . . . . . . . | .08 | .08 |

| Trends . . . . . . . . . . | .03 | .03 |

| Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .04 | .04 |

Notes.—Results for the correlation between issues and (A) party identification and (B) liberal-conservative political ideology. Varying-intercept and varying-slope models; 47 pairs, 383 observations.The time variable is zeroed at 1980, and thus the intercept corresponds to the estimate for that year. Numbers in parentheses are SEs.

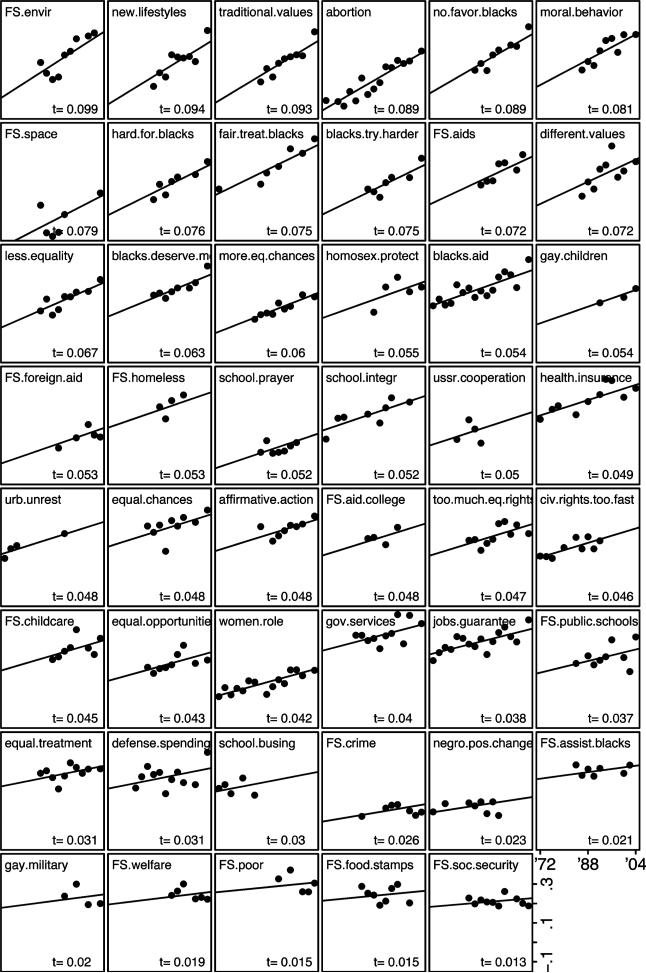

Consider in detail the model for party identification. The average correlation between issues and party identification is .17, with an estimated standard deviation among issues of .08, which means that about two-thirds of the correlations are in the interval between .09 and .25. This confirms that the level of constraint of opinions and partisanship is low: party identification predicts, on average, only the 17% of people's opinions on political issues. Central to our analysis is the coefficient estimate for the time parameter t: on average, correlations have increased by .05 per decade (SE = .01). With a standard deviation of .03, most of the trends are positive, with an estimated 95% between –.01 and .11. This suggests that, for almost all issues, trends are either positive or close to zero. To portray this result graphically, figure 3 plots the trend of the correlations for all the issues along with the regression line from the multilevel model. Issues are sorted according to the intensity of the change over time, starting from those that show the steepest increase, such as (perhaps surprisingly) federal spending for the environment and (less surprisingly) new lifestyles, traditional values, abortion, affirmative action, and moral behavior, to those that are stable overall, such as federal spending on welfare, the poor, food stamps, and social security.

Fig. 3.

Trends in the correlation between issues and party identification. Regression lines as estimated in equation (1); at the bottom of each plot is reported the coefficient ti. The x-axis is time (1972–2004), and the y-axis is correlation (–.1 to .4).

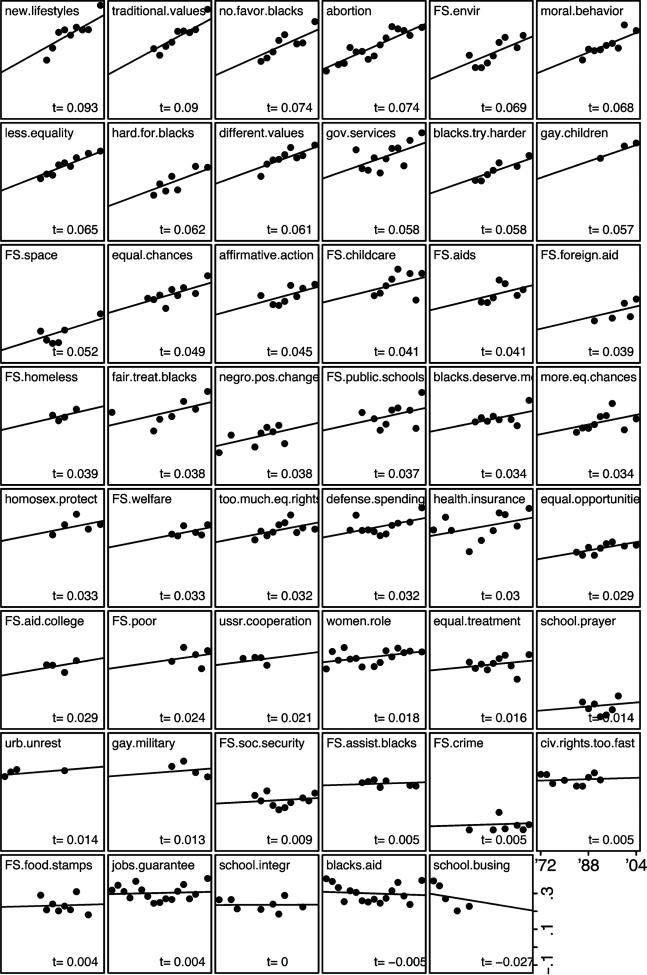

Modeling the correlation between issues and political ideology, we obtain similar results (see table 1, col. A). In this case, the mean correlation is .22, and the correlations increase, on average, by .04 every 10 years. Again, most of the change is in the direction of a strengthened relation between issues and ideology, as the plots in figure 4 demonstrate. Here, we report the trend over time of the correlation between each issue and self-placement on the liberal-conservative scale. With only few exceptions, the slopes are positive or close to zero.

Fig. 4.

Trends in the correlation between issues and political ideology. Regression lines as estimated in equation (1); at the bottom of each plot is reported the coefficient ti. The x-axis is time (1972–2004), and the y-axis is correlation (–.1 to .5).

In sum, our results suggest that issue partisanship has increased over time. Nonetheless, as a careful inspection of figures 3 and 4 indicates, it is possible that the rise in the correlations has occurred mostly (or only) in some issue domains and less (or not) in others. To test this hypothesis, we specify a model that distinguishes issue types according to the four issue domains. Results are reported in table 2. With respect to both party identification and political ideology, we notice that economic issues have the highest average correlation (.24 in both cases), followed by civil rights issues (.18 and .22, respectively), moral issues (.11 and .20), and foreign policy issues (.10 and .16). More interesting, the temporal variations of the correlation coefficients vary among issue domains. For economic issues the increase is, on average, .04 per decade with party identification and .03 with political ideology, but the correlations of moral issues with party and ideology have grown by .08 and .07 per decade, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Correlation Results from Multilevel Models for Issue Partisanship by Issue Domains

| ρ ≡ Issue × Party ID | ρ ≡ Issue × Ideology | |

|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | |

| Intercept . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .24 (.02) | .24 (.02) |

| Economic issues . . . . . . . . . . . . | baseline | baseline |

| Civil rights issues . . . . . . . . . . | –.06 (.02) | –.02 (.03) |

| Moral issues . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | –.13 (.03) | –.01 (.03) |

| Foreign policy issues . . . . . . . | –.14 (.03) | –.08 (.04) |

| Time (decades) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .04 (.01) | .03 (.01) |

| Time × economic . . . . . . . . . . | baseline | baseline |

| Time × civil rights . . . . . . . . | .02 (.01) | .01 (.01) |

| Time × moral . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .04 (.02) | .04 (.02) |

| Time × foreign policy . . . . . | .00 (.02) | .00 (.02) |

| Residual SD: | ||

| Intercepts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .06 | .08 |

| Trends . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .03 | .03 |

| Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .04 | .04 |

Notes.—Results for the correlation between issues and (A) party identification and (B) liberal-conservative ideology. Varying-intercept and varying-slope models; 47 pairs, 383 observations. The time variable is zeroed at 1980, and thus the intercept corresponds to the estimate for that year. Numbers in parentheses are SEs.

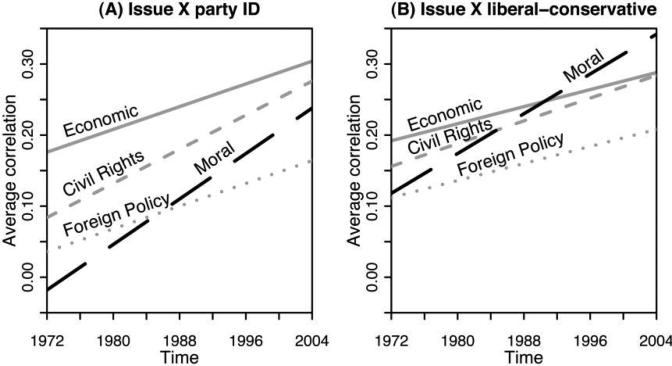

Figure 5 summarizes these trends and allows a direct comparison of the four issue domains. Both measures of partisanship show similar patterns: since the beginning of the time period considered here, economic issues have been the most partisanly aligned, followed by civil rights and then foreign policy and moral issues. While the increment has proceeded more or less at the same pace in the first three issue domains, thus keeping stable the distance between these domains, the partisanship of moral issues has grown faster, to the point that moral issues have substantially reduced the gap with other issue domains in regard to their correlation with party identification (starting from a situation, in the 1970s, in which there was virtually no relation). Even more striking, with respect to political ideology, the domain of moral issues has recently become the most partisan among the four.

Fig. 5.

Trends in issue partisanship for different issue domains

We conclude that issue partisanship has increased in all issue domains, although at different speeds, and that citizens now divide along ideological lines not only on economic and civil rights issues but also on matters of morality. This tendency in issue partisanship was somewhat expected. Our goal is now to assess if the increased coherence between issue preferences and party affiliation or ideology is simply the by-product of the strengthened partisanship and polarization of parties or, instead, if it is the case that increasing issue partisanship goes along with increasing issue alignment. In other words, we will investigate whether people now are not only better at combining their opinions with their partisanship but also show greater coherence in combining their preferences on multiple issues.

Analysis 2: Issue Alignment

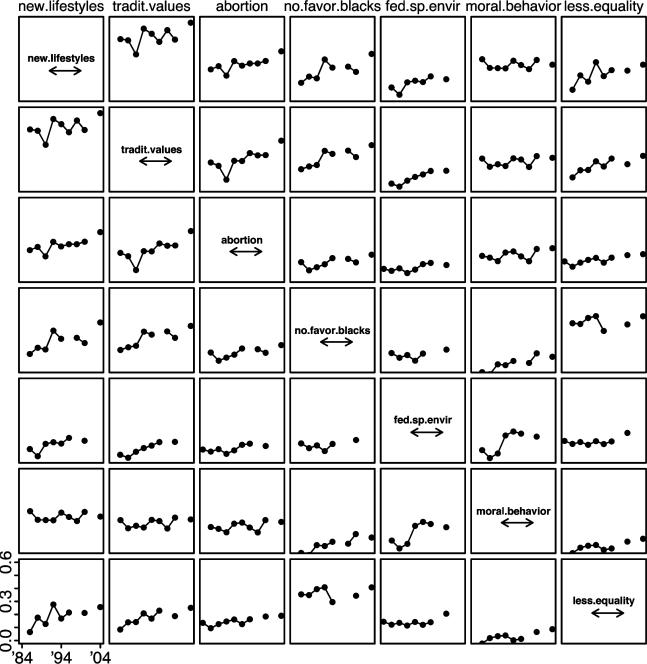

One can have a first, suggestive idea of the trend in issue alignment by looking at the correlation between pairs of issues over time. Unfortunately, since 47 issues generate 1,081 potential pairs, we cannot show the trend for all pairs. Logically, one would expect the greatest increase in correlations among pairs of issues that have had the steepest increase in partisanship. Accordingly, we select the seven issues with the highest correlation with party identification and ideology (figs. 3 and 4 reveal that the top issues are almost the same in both instances). These issues include new lifestyles, traditional values, abortion, affirmative action, federal spending for the environment, moral behavior, and equality. Figure 6 plots the correlation between these pairs of issues over time. Despite their increase in partisanship over the past few decades, the correlation between these issues seems to have remained stable or, in a few cases, increased only modestly. This offers scarce support to the hypothesis of issue alignment (hypothesis 2a).13 Compare this result to figures 3 and 4, which show much more dramatic increases in issue partisanship.

Fig. 6.

Trends in correlations between pairs of hot issues. The x-axis is time (1984–2004), and the y-axis is correlation (0 to .6). The plots are redundant: each pair of issues is plotted twice so that the reader can see on the same row (or column) the correlation between one issue and all the others.

To test this hypothesis more formally, we deploy a model that is similar to the one described previously. Namely, we run a multilevel model with varying intercept and varying slope in which the unit of analysis is issue-pair correlations × year. Formally,

| (2) |

where ρpt is the correlation between the pair of issues p in the year t. Results are shown in part A of table 3.

TABLE 3.

Correlation Results from Fitted Multilevel Models for Issue Alignment

| Model | ρ ≡ Pairs of Issues |

|---|---|

| A. No grouping of pairs: | |

| Intercept . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .15 (.00) |

| Time (decades) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .02 (.00) |

| Residual SD: | |

| Intercepts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .11 |

| Trends . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .02 |

| Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .04 |

| B. Within and between issue domains: | |

| Intercept . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .12 (.00) |

| Within domain pairs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .11 (.01) |

| Time (decades) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .02 (.00) |

| Time × within domain . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .00 (.00) |

| Residual SD: | |

| Intercepts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .09 |

| Trends . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .02 |

| Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .04 |

| C. Types of issue domains: | |

| Intercept . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .25 (.01) |

| Economic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | baseline |

| Civil rights . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .00 (.01) |

| Moral . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | –.07 (.02) |

| Foreign policy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | –.23 (.03) |

| Mixed pairs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | –.14 (.01) |

| Time (decades) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .02 (.00) |

| Time × economic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | baseline |

| Time × civil rights . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .00 (.01) |

| Time × moral . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .00 (.01) |

| Time × foreign policy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .00 (.02) |

| Time × mixed pairs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .00 (.00) |

| Residual SD: | |

| Intercepts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .09 |

| Trends) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .02 |

| Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | .04 |

Notes.—Results for the correlation between pairs of issues in (A) a model with no grouping of pairs, (B) a model with pairs grouped by location within or between domains, and (C) a model with pairs grouped by issue domain. Varying-intercept and varying-slope models; 1,054 pairs, 5,635 observations. Numbers in parentheses are SEs.

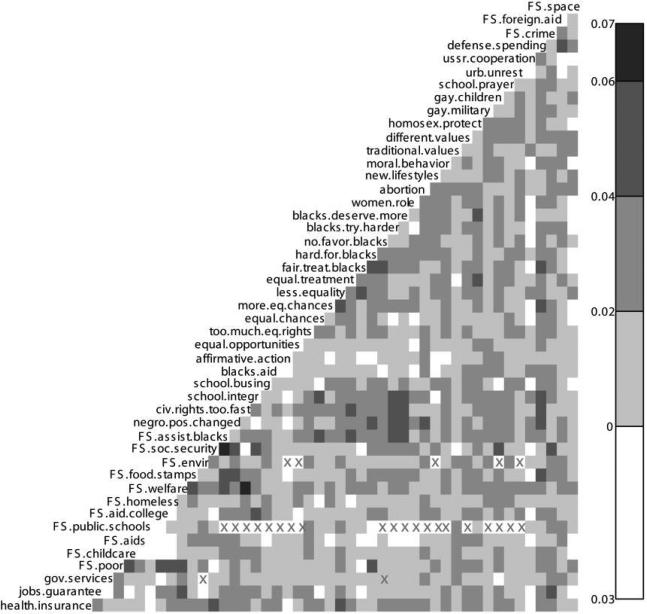

The average correlation between issues is .15, with a standard deviation of .11, which means that about two-thirds of the pairs’ correlations range between .04 and .26. With respect to the trend in issue alignment, we observe that, on average, the coefficients have increased by .02 per decade. Although statistically significant (SE = .00), this trend is substantially lower than the one observed for issue partisanship. Moreover, the estimate coefficient is close to zero or even negative for most of the pairs: 95% of issue pairs show trends between –.02 and .06. Figure 7 plots the trend βt estimate for each pair of issues. We highlight the intensity of the change using different shades of gray. Correlation between issues has substantially increased in only a few cases; moreover, there are no discernible patterns within or between issue domains.

Fig. 7.

Time trends in correlations for all pairs of issues. The plot shows the trend estimates for each pair of issues from the multilevel model for issue alignment as estimated in equation (2) (a summary of the model is presented in table 3, model A). X's indicate pairs for which no observation was available (to compute the estimate, it was necessary for both issues in a pair to have been asked about in at least two different years).

According to our hypothesis 2a, issue alignment is expected to induce increased correlation between issue domains, as a consequence of the increased coherence in people's belief systems. We test this hypothesis first by distinguishing between pairs that belong to the same domain and those that belong to two different domains. In model B of table 3, we report the results of this test. At any time, we expect higher correlation between issues that belong to the same domain, and in fact the average correlation is .23 for within-domain pairs and .12 for between-domain pairs. In the case of issue alignment, we would expect to observe coefficients for between-domain pairs growing more substantially than the coefficients of pair correlations within domains. However, this is not what we find: the modest growth of .02 per decade affects within- and between-domain pairs alike.

It might be the case, nonetheless, that issue alignment is occurring only between some domains. In particular, since we have observed a substantial increase of partisanship with respect to moral issues, we might expect opinions on moral issues to have become more constrained. Model C of table 3 induces us to reject this hypothesis. In this model, we distinguish pairs according to their issue domain. The correlation within issue domains is, on average, .25 for economic and civil rights issues, lower for moral issues (.18), and generally null for foreign policy issues. The average correlation for between-domain (mixed) pairs is .11. Once again, we find that the intensity of change over time is the same within and between issue domains.

In sum, evidence in favor of our hypothesis on issue alignment is limited to a modest trend of increasing correlation between pairs of issues. Moreover, this trend is undifferentiated (since it manifests within each issue domain and between domains in similar ways) and not generalized (since several issues show no tendency toward alignment and some are even moving toward dealignment). This is too little evidence, we conclude, to talk about actual issue alignment.

Nonetheless, it is possible that different patterns in issue partisanship and alignment are occurring within subsets of the population or subgroups of people. This is the subject of our last set of analyses.

Analysis 3: Partisanship and Alignment in Subgroups

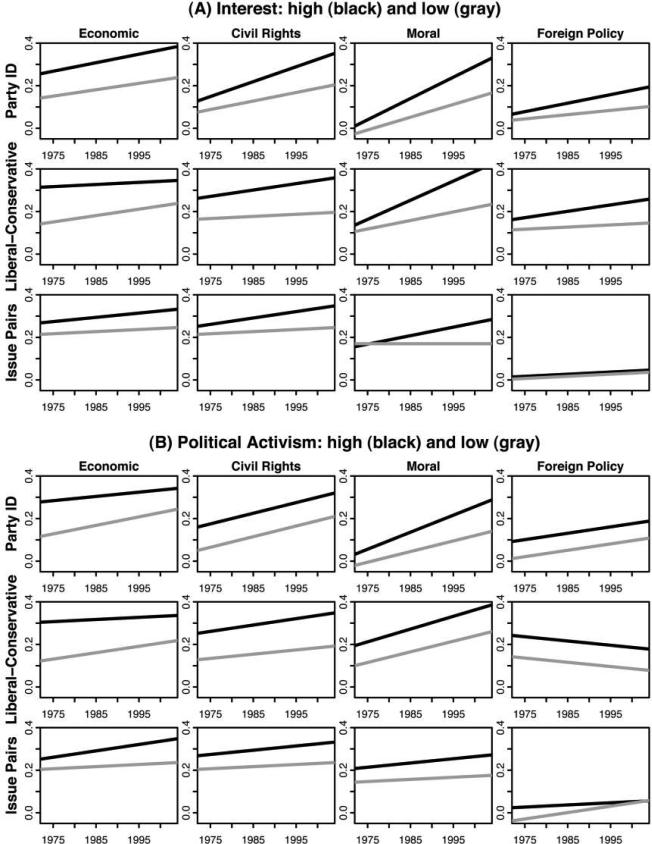

Patterns observed in the population as a whole might hide trends in population subgroups or even cancel out contrasting trends. Hypothesis 2b considers the subset of the population that is politically more sophisticated or active. Some citizens are more interested in politics than others and thus, on average, have a more structured political belief system. Their opinions show higher constraint and are more consistent over time. The question for us is whether patterns in partisanship and issue alignment are different among the politically sophisticated. The following analysis shows that, indeed, they are.

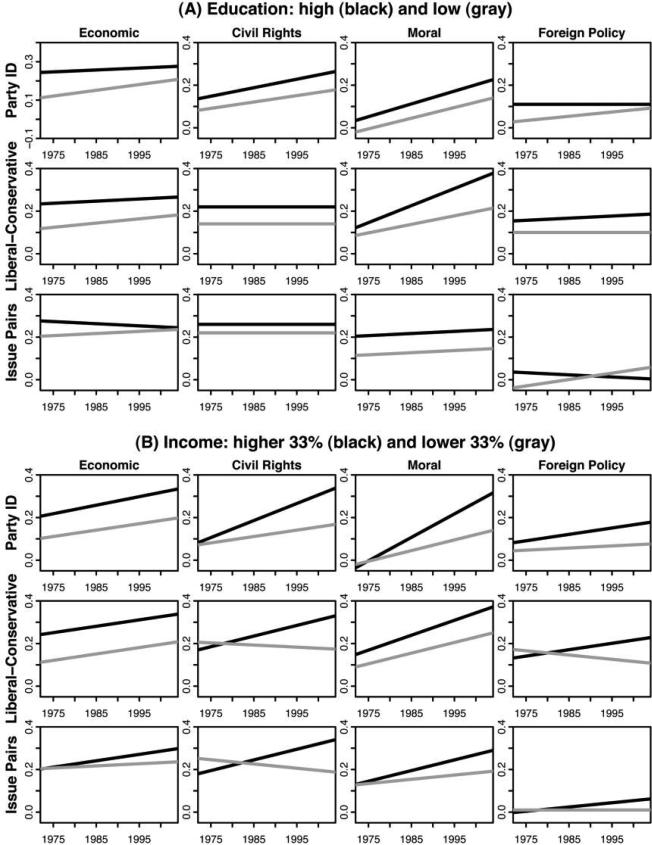

Part A of figure 8 shows the trends in partisanship and issue alignment, distinguishing highly interested people (black line) from people who follow politics only sporadically (gray line). Each row reports the results from a multilevel regression model with varying intercept, varying slope, and correlations grouped by issue domain. The first and second row report models of issue partisanship, issue × party identification and issue × political ideology, respectively; the third row reports estimates for the model of issue alignment (issue-pair correlations). As expected, those who are interested in politics show higher levels of issue constraint. Moreover, issue partisanship on civil rights and moral issues has increased at a faster pace among those who are interested in politics. And a similar, although less pronounced, trend is visible for issue alignment.

Fig. 8.

Trends in issue partisanship and alignment for different levels of interest and political activism. Estimates from the multilevel regression models with varying intercept, varying slope, and correlations grouped by issue domain. Each box compares the correlation trends in an issue domain for two mutually exclusive subgroups. The x-axis is time (1972–2004), and the y-axis is correlation (–.05 to .4).

Part B of figure 8 compares the trend for political activists to the rest of the population. As was true of the subset of interested citizens, politically active people have higher issue constraint. But their change over time is parallel to that of other citizens, a result suggesting that dynamics of issue partisanship and alignment are more related to cognitive capabilities than to partisan political involvement (although the two often go together).

We use the same analytical strategy to test hypothesis 2c, considering first population subgroups defined by education and income (see fig. 9). While people who attended college differ from those who did not only in terms of their overall level of constraint (fig. 9, part A), profound differences exist between the wealthiest—the top 33% of the income distribution—and the poorest people—the bottom 33% of the income distribution (fig. 9, part B). Over time, the wealthiest part of the population has become more ideological and internally more consistent on civil rights and moral issues. In contrast, the poorest third shows minimal (or even decreasing) partisanship and issue alignment on civil rights issues and a moderate growth in partisanship and alignment on moral issues. While the richest part of the nation has sorted along partisan lines, the poorest part has not (or not to the same extent). In line with recent studies on the relation between inequality and politics (McCarty et al. 2006), this result seems to suggest that economically marginal individuals are growing increasingly more detached from the political discourse.

Fig. 9.

Trends in issue partisanship and alignment for different levels of education and income. Estimates from the multilevel regression models with varying intercept, varying slope, and correlations grouped by issue domain. Each box compares the correlation trends in an issue domain for two mutually exclusive subgroups. The x-axis is time (1972–2004), and the y-axis is correlation (–.05 to .4). In the education models, high education means college or higher, low education means no college.

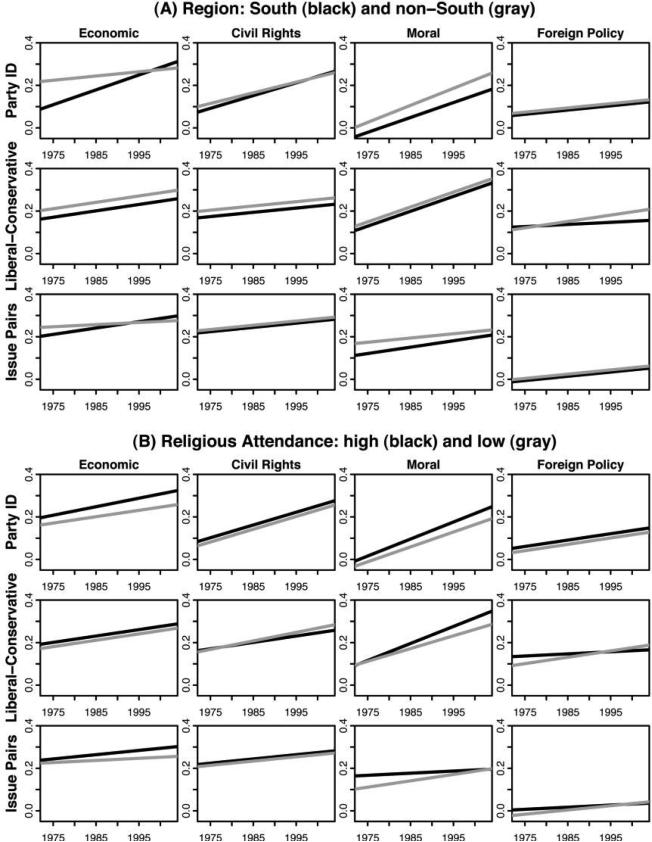

Figure 10 considers two factors that have been often associated with the current wave of polarization: region and religious attendance. Perhaps surprising to some, the process of partisan realignment along moral issues has taken place in the same way among southerners and nonsoutherners and among churchgoers and nonchurchgoers. The only remarkable difference is the strong party realignment of southerners on economic issues. This does not mean that people in these different subgroups think alike—indeed, they do not (Ansolabehere et al. 2006b)—but it means that patterns of increasing polarization on moral issues are not disproportionally driven by some population subgroups. They involve the entire population.

Fig. 10.

Trends in issue partisanship and alignment by region and religious attendance. Estimates from the multilevel regression models with varying intercept, varying slope, and correlations grouped by issue domain. Each box compares the correlation trends in an issue domain for two mutually exclusive subgroups. The x-axis is time (1972–2004), and the y-axis is correlation (–.05 to .4).In the religious attendance models, high attendance means twice a month or more, and low attendance means less than twice a month.

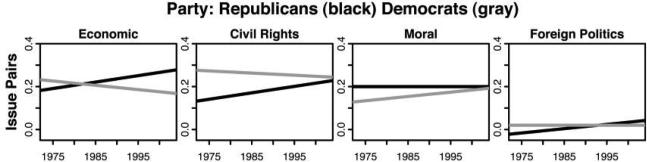

Last, we consider the possibility that issue alignment has occurred among party voters (hypothesis 2d). Looking separately at trends among Republican and Democratic voters (see fig. 11), we find clear evidence of increasing constraint within issue domains, especially among Republicans. In fact, Republicans have become more consistent on economic and civil rights issues, while Democrats have lost constraint on these issues and become a bit more coherent in their moral views. In both groups of voters, the constraint is growing faster than in the populace as a whole. Overall, alignment has occurred among party voters, but asymmetrically. Republicans are aligning on social themes, whereas Democrats are catching up on moral issues. In neither group is there evidence of alignment along issue domains.14 This reinforces our argument about the role of parties in sorting voters along partisan lines, but it simultaneously suggests that the increasing coherence of party voters—who are usually the primary concern for many elected officials—might have (or have had) an impact on the views and strategies of the political elite.

Fig. 11.

Trends in issue alignment, separately considering Democratic and Republican voters. Estimates from the multilevel regression models with varying intercept, varying slope, and correlations grouped by issue domain. The x-axis is time (1972–2004), and the y-axis is correlation (–.05 to .4).

DISCUSSION

Why are Americans so worried about political polarization? And should they be worried? Scholars and pundits seem to be concerned with polarization because of its consequences for interest representation, political integration, and social stability. Political polarization constitutes a threat to the extent that it induces alignment along multiple lines of potential conflict and organizes individuals and groups around exclusive identities, thus crystallizing the public arena into opposite factions. In contrast, intrasocial conflict is sustainable as long as there are multiple and non-overlapping lines of disagreement. Starting from these premises, we have argued that polarization has to be conceived not only as a phenomenon of opinion radicalization, but also as a process of ideological division and preference alignment.

Thinking of polarization as a process of alignment along multiple dimensions of potential conflict led us not simply to study an aspect of polarization yet to be considered, but also to address broader concerns related to its potential consequences for the political process and to ask to what extent contemporary America is moving away from the ideal of political pluralism. By distinguishing between trends in issue partisanship and issue alignment, we were able to disentangle dynamics of interest alignment that might sharpen divisions in the political arena and of group or partisan sorting that might give disproportionate voice to certain population subgroups and lead to the systematic underrepresentation of others, thus making the democratic process more unequal. In the next paragraphs, we summarize our main findings and discuss their potential consequences for political representation.

In general, we have found that people's preferences are loosely connected, and even the correlation between their preferences and partisan-ship is low. But this alone cannot be regarded as a decisive proof of the crosscutting nature of people's political interests, since such a low level of constraint is only partially interpretable as an indicator of the composite, multifaceted nature of people's political views. The scarce coherence in people's attitudes is to some extent due to their low level of political sophistication: in fact, much of the population is not interested in politics, does not follow political debate, and is minimally capable of organizing its preferences according to classical ideological categories (Converse 1964; Delli Carpini and Keeter 1996). That said, it is nonetheless informative to look at temporal and group variations in levels of issue constraint.

We first considered the trend of issue partisanship over time and concluded that the relation between people's political attitudes and their party identification or political ideology has tightened. A substantial growth in the correlation between issues and partisanship is observable for all issue domains, but the change is significantly more intense in the case of moral issues. At the beginning of the 1970s, the partisan divide was visible only for economic and, to a lesser extent, civil rights issues. Thirty years later, Democrats and Republicans (and liberals and conservatives) divided in their opinions on moral issues as well. The economic domain remains the most tightly related to party identification, followed by civil rights and moral issues, while, with respect to political ideology, moral issues are now the most distinct dividing line.

In general, our analysis adds to other scholars’ findings on the increasing importance of partisanship: we show that partisanship not only has an impact on voting behavior (Bartels 2000; Hetherington 2001), but plays a more important role in partitioning voters according to their issue preferences. We confirm that moral issues have become a stable component of partisan identities, but we argue that it is by no means the only (or the most important) one. Manza and Brooks (1999) have convincingly supported the persistent importance of traditional social cleavages of class, race, and religiosity in determining voting behavior. Accordingly, our study shows that individuals have become more partisan not only on moral issues, but also on economics and civil rights.

Second, we turned to the study of issue alignment, modeling the correlation between pairs of issues, and found only feeble evidence of issue alignment. We observe a minimal increase in the correlations; moreover, the trend does not differentiate pairs of issues within and across issue domains, and it does not involve a large group of issues or a meaningful subset of them.

Taken together, these two results support our hypothesis 1, suggesting that changes in the electorate should be interpreted as an illusory adjustment of citizens to the renovated partisanship of the political elite. In other words, since the parties are now more clearly divided—and on a broader set of issues—it is easier for people to split accordingly, without changing their own views (this is why we use the term illusory). There has been some discussion regarding the directionality of the change, with most scholars suggesting that public opinion polarization is a consequence of elite polarization (Layman et al. 2006). Our results confirm this interpretation, since, despite partisan alignment, we found no real instances of issue alignment. If it were the case that changes in voters’ preferences had affected the party elite, we would instead have found evidence of issue alignment in the electorate, since issue alignment has certainly occurred among the political elite (Poole and Rosenthal 2007). Nonetheless, as we will discuss later, the sorting of voters along party lines is likely to have had an impact on parties’ strategies.

So far, we have reviewed changes in the entire population. Further examining trends in issue partisanship and alignment within population subgroups allowed us to reveal potential mechanisms of unequal representation. Population subgroups differ in their overall levels of constraint: people who are wealthier, more educated, and interested in politics show, at any moment in time, higher correlations in issue attitudes than other members of the population. More interestingly, in some cases, trends in issue partisanship and alignment also differ. Specifically, we noticed that those who are more interested in politics have grown more coherent in their beliefs on moral and civil rights issues at a faster pace than the remainder of the population, thus broadening the gap between these groups’ respective levels of constraint on these issues. A similar and more striking pattern was observed among the richest third of the population, who have become more coherent in their political preferences, and in the relation between these preferences and partisanship, while the poorest have remained essentially inconsistent. We do not observe any pattern, however, when dividing the population by region or by church attendance.

Our work reinforces the findings of McCarty et al. (2006) on the relation between elite polarization and inequality by suggesting that substantial partisan and issue alignment has occurred within the resourceful and powerful group of rich Americans. The wealthier part of the political constituency knows well what it wants, and it is likely, now more than in the past, to affect the political process. This potentially increases inequality in interest representation, not only through lobbying activity and campaign financing, but also in the ballot (Bartels 2008).15

Finally, issue alignment has occurred among party voters, with Republicans becoming more coherent in their economic and civil rights preferences and Democrats lining up on moral issues. Party voters are more divided and therefore constitute an easily identifiable target for a party elite concerned with preserving its constituency. Since parties pay some attention to voters in defining their strategies and political agenda (Stimson 2004; McCarty et al. 2006), nonvoters, by not showing up at the polls, are undermining their representation capacity both because they do not get to choose their representatives and because parties’ strategies are less likely to consider their preferences.

Moreover, it is possible that extreme positions have gained prominence within the two parties: given the partisan realignment, the average opinion within partisan subgroups is now more extreme, as documented, for instance, by Shapiro and Bafumi (2006). Party voters, having become more consistent in their political preferences, are likely to convey more extreme preferences to their party leaders. In addition, given the asymmetries in issue alignment in the two parties, it is reasonable that voters are splitting along party lines according to the issues that are most salient to them, while they do not bother to adjust their (weak) preferences on the remaining issues (Baldassarri and Bearman 2007). This, in turn, gives more leverage to the actions of single-issue advocates and interest groups, which tend to hold extreme positions (Brady and Han 2006; McCarty et al. 2006).

Voting, of course, is not the only way in which citizens can exercise their political influence. In addition, some scholars have argued that, especially in recent decades, new, individualized forms of civic participation have come to permeate large spheres of social life (Schudson 1998; Perrin 2006). Nonetheless, the rise of new participatory forms, or even new forms of citizenship—Schudson's model of “monitoring citizenship”—do not per se eliminate the impact that partisan sorting and biases in group representation might have on the political outcome. Indeed, new participatory forms, especially those requiring supervising and communicative capacity, might be affected by the same asymmetries that characterize traditional ones.

To summarize, we have found that the main change in people's attitudes has more to do with a resorting of party labels among voters than with greater constraint in their issue attitudes. This has occurred mostly because parties are more polarized and therefore better at sorting individuals along ideological lines. Such partisan realignment, although it has not induced realignment in issue preferences, does not come without consequences for the political process. In fact, party polarization may have gained momentum as party voters have become more divided. This, we believe, is the feedback mechanism that has allowed parties to continue to polarize and still win elections. In addition, increased issue partisanship, in a context in which the issue constraint of the general public is extremely low, may have had the effect of handing over greater voice to political extremists, single-issue advocates, and wealthier and more educated citizens, thus amplifying the dynamics of unequal representation.

Footnotes

We thank Peter Bearman, Mario Diani, Aleks Jakulin, Shigeo Hirano, Michael Hout, Arthur Stinchcombe, Robert Shapiro, Yu-Sung Su, the AJS reviewers, and the participants in the Quantitative Political Science workshop at Columbia University for helpful comments. We also thank the Applied Statistics Center and the Institute of Social and Economic Research and Policy at Columbia University, the National Science Foundation, and the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies for financial support.

As argued, e.g., by James Madison in number 10 of the Federalist Papers (Hamilton, Madison, and Jay [1787] 1961).

Like any theory of democracy, political pluralism is, first and foremost, a political philosophy. As such, it might appear ill suited to empirical analysis. Nonetheless, several aspects of the current regulatory system (e.g., norms of party and interest-group competition and division of power, as well as many social policies) are based on the principles and justified according to the logic of political pluralism, making the goal of assessing the validity of its assumptions crucial to both supporters and skeptics of this political theory.

It is hard to come up with a good terminology. What we call issue partisanship has been also referred to as partisan sorting (see Hetherington, in press). Moreover, to study issue alignment we use Converse's (1964) measure of constraint. Nonetheless, we use the term issue alignment instead of constraint, which is most common, because we focus on alignment between issue domains; we only marginally engage the debate on the constraint of mass political belief systems.

For Brady and Han (2006), this disconnect is due to a lag in the nationalization of congressional elections. Polarization in presidential elections has increased, starting in the mid-1960s, while congressional elections have resisted such polarizing trends, and cross-party voting persisted through the early 1990s.

In statistics, this is called k-means clustering, in this case with k = 2; in the special case of the multivariate normal distribution, the clusters are determined by a plane slicing diagonally through the space.

We present results using Pearson correlations. Similar results are obtained using other correlation measures.

We fit the models using the lmer function in R, which estimates multilevel models using a point estimate for the group-level variance parameters; this works well as long as the group-level variances are separate from 0 and group-level correlations are separate from ± 1 (see, e.g., Gelman and Hill 2007).

The NES data are available from the Center for Political Studies at the University of Michigan.

All the analyses were also performed on the 1948–2004 time period, and no substantive differences were found.

To assess the robustness of the classification, we relied on the principles of intercoder reliability. Four different people were asked to independently classify the attitude questions. Differences were minor, occuring for only three questions. Moreover, the classification of these questions does not substantially change the results reported here. It may seem strange, e.g., that the question on urban unrest is included within security and foreign policy. Another option would be to characterize urban unrest as a civil rights issue. But doing so does not change our results, except for increasing the uncertainty in the estimates for security and foreign policy, because this domain has relatively few questions.

The variable t is expressed in decades and centered in 1988 so that the intercepts and slopes can be more directly interpreted. Formally, t = (year – 1988)/10.

Alternatively, one can aggregate survey items on the same issue domain. Following this strategy, we confirm the findings of Ansolabehere et al. (2006a): when we look at averages and when the number of items increases, we observe higher constraint between issue domains.

Results not shown are available from the authors.

We are not suggesting that rich people all think the same; in fact, they show great variation in their partisanship (Manza and Brooks 1999; Bafumi and Shapiro 2007; Gelman, Shor, et al. 2007; Gelman, Park, et al. 2008). We are saying that, whether Republican or Democratic, rich people have a more coherent political agenda, making them more capable of pushing through the system whatever issue they care about.

Contributor Information

Delia Baldassarri, Princeton University.

Andrew Gelman, Columbia University.

REFERENCES

- Abramowitz Alan I., Saunders Kyle L. Ideological Realignment in the U.S. Electorate. Journal of Politics. 1998;60:634–52. [Google Scholar]

- Abramowitz Alan I., Saunders Kyle L. Why Can't We All Just Get Along? The Reality of Polarized America. The Forum. 2005;3(2) http://www.bepress.com/forum/vol3/iss2/art1. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich John. Why Parties? The Origin and Transformation of Party Politics in America. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ansolabehere Stephen, Rodden Jonathan, Snyder James M., Jr. Working paper. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Political Science; 2006a. Issue Preferences and Measurement Error. [Google Scholar]

- Ansolabehere Stephen, Rodden Jonathan, Snyder James M., Jr. Purple America. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2006b;20(2):97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Ansolabehere Stephen, Snyder James. The End of Inequality. Norton; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bafumi Joseph. The Stubborn American Voter.. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association; Chicago. September 2.2004. [Google Scholar]