Abstract

Objective

Optimism has been associated with a lower risk of rehospitalization after coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, but little is known about how optimism affects treatment of depression in post-CABG patients.

Methods

Using data from a collaborative care intervention trial for post-CABG depression, we conducted exploratory post hoc analyses of 284 depressed post-CABG patients (2-week posthospitalization score in the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire ≥10) and 146 controls without depression who completed the Life Orientation Test – Revised (full scale and subscale) to assess dispositional optimism. We classified patients as optimists and pessimists based on the sample-specific Life Orientation Test – Revised distributions in each cohort (full sample, depressed, nondepressed). For 8 months, we assessed health-related quality of life (using the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey) and mood symptoms (using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HRS-D]) and adjudicated all-cause rehospitalization. We defined treatment response as a 50% or higher decline in HRS-D score from baseline.

Results

Compared with pessimists, optimists had lower baseline mean HRS-D scores (8 versus 15, p = .001). Among depressed patients, optimists were more likely to respond to treatment at 8 months (58% versus 27%, odds ratio = 3.02, 95% confidence interval = 1.28–7.13, p = .01), a finding that was not sustained in the intervention group. The optimism subscale, but not the pessimism subscale, predicted treatment response. By 8 months, optimists were less likely to be rehospitalized (odds ratio = 0.54, 95% confidence interval = 0.32–0.93, p = .03).

Conclusions

Among depressed post-CABG patients, optimists responded to depression treatment at higher rates. Independent of depression, optimists were less likely to be rehospitalized by 8 months after CABG. Further research should explore the impact of optimism on these and other important long-term post-CABG outcomes.

Keywords: optimism, pessimism, depression, coronary artery bypass graft, collaborative care, randomized controlled trial

INTRODUCTION

Optimism, or a person's expectation that good things will happen, has been associated with favorable cardiac and other health-related outcomes. Optimistic postmenopausal women have a lower risk of first myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease–related mortality, and all-cause mortality than those who report to be pessimistic (1), a finding that has also been documented in older men (2,3). Compared to pessimists, optimistic individuals have a lower risk of subclinical cardiovascular disease (CVD) progression (4) and lower rates of rehospitalization after coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery (5). However, the previous study on rehospitalization did not select for depression, and thus, results may not apply to a depressed population.

Depressive symptoms are common after CABG surgery (6) and are associated with worse clinical outcomes, including poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and functional status (7), persistent chest pain (8,9), higher rates of hospitalization, and death (10–14). Optimism is negatively associated with depressive symptoms (1) and with reduced incidence of depression during long-term follow-up (15). However, the impact of optimism in predicting success for treatment of depression after CABG has not been studied. Although the precise mechanisms underlying the relationship between optimism and cardiovascular health remain unclear, optimism may modify the experience of mood symptoms, which have been linked to increased risk of cardiovascular events. Optimists cope more effectively with adversity and are more likely to engage in health-promoting behaviors (16). They may also be more adherent to medical treatment (17).

Optimism and pessimism have usually been considered as anchors on opposite ends of the same spectrum (i.e., optimism/pessimism is a bipolar trait). However, a growing body of literature recognizes that these traits may not be mutually exclusive and may thus contribute independently to health (i.e., optimism and pessimism are unipolar traits). Accordingly, these studies have included analyses designed to disaggregate optimism from pessimism and have tended to conclude that pessimism is more robustly related to health, even after controlling for the degree of optimism (18–22).

We examined these issues in a secondary analysis of data from the Bypassing the Blues study (23,24), the first randomized controlled trial (RCT) designed to examine the impact of telephone-delivered collaborative care for treating post-CABG depression on HRQoL, physical functioning, and mood (23). We hypothesized that depressed individuals reporting high optimism (versus those with high pessimism) would demonstrate: a) more favorable baseline profiles of sociodemographic, clinical, psychiatric, and HRQoL variables; b) higher rates of response to treatment of depression after CABG; and c) lower rates of rehospitalization after CABG independent of their depressive moods. We further attempted to disaggregate optimism from pessimism to determine whether either trait was independently related to the outcomes of interest.

METHODS

The research design for the Bypassing the Blues Study has been detailed previously (23,24) and was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pittsburgh and each participating hospital.

Participants

Post-CABG patients were recruited before hospital discharge at two university-affiliated and five community-based hospitals in the greater Pittsburgh, PA, region between 2004 and 2007. Trained nurse-recruiters were directed to medically stable post-CABG patients at each study site and obtained their signed informed consent to undergo screening with the two-item version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) (25). An affirmative answer to either the mood or the anhedonia question was considered a positive depression screen.

Because mood symptoms such as fatigue and sleeplessness commonly follow CABG surgery and possibly represent the routine sequelae of this surgery, patients were administered the full PHQ-9 (26) via telephone 2 weeks after hospital discharge to confirm the positive PHQ-2 inpatient depression screen. Those who scored 10 or higher on the PHQ-9, signifying at least a moderate level of depressive distress, remained protocol-eligible. Nurse-recruiters also enrolled 151 patients who screened negative on the PHQ-2 before discharge, were not using antidepressants, met all other protocol eligibility criteria, and scored less than 5 on the 2-week PHQ-9 into the nondepressed cohort.

Final Study Sample

This report focuses on the 430 post-CABG patients who completed the Life Orientation Test – Revised (LOT-R), the measure of optimism/pessimism (see next section), including 284 of the depressed cohort (PHQ-2 [+]/PHQ-9 ≥10) and 146 of the nondepressed controls (PHQ-2 [–]/PHQ-9 <5). There were 23 subjects of the original sample who did not complete the LOT-R and who were therefore not included. These subjects did not differ significantly from LOT-R completers in age, sex, race, and marital status.

Definition of Optimism and Pessimism

LOT-R Full Scale (Optimism/Pessimism as a Bipolar Trait)

An individual's degree of optimism or pessimism is considered a personality trait (27) and may be assessed by several validated scales. Optimism and pessimism have been associated with self-reported health outcomes including subjective well-being and HRQoL, in addition to adjudicated health outcomes such as incident CVD and mortality (28,29). The LOT-R (30) is a standardized measure of optimism/pessimism that was administered to all participants after confirmation of participant eligibility at the 2-week follow-up. The six items, each rated from 0 to 4, yield a total score ranging from 0 to 24. In this full-scale measure, higher scores indicated greater optimism, whereas lower scores indicated greater pessimism. LOT-R scores were first categorized into approximate quartiles based on the full sample distribution, with the following cutoffs in the full sample: highest (19+) (termed optimists), mid high (between 17 and 18), mid low (between 14 and 16), and lowest (<14) (termed pessimists). We further calculated sample-specific quartiles as follows: higher than 18, between 16 and 17, between 13 and 15, and 12 or lower in the depressed cohort (n = 284) and as higher than 20, between 18 and 19, between 15 and 17, and 14 or lower in the nondepressed cohort (n = 146). These sample-specific quartiles were used in stratified analyses. LOT-R scores were also considered separately as a continuous variable.

LOT-R Subscales (Optimism and Pessimism as Unipolar Traits)

To disaggregate optimism from pessimism, we also considered each subscale of the LOT-R separately. The optimism subscale was the sum of the three positively worded questions to yield a total score ranging from 0 to 12 (higher scores indicating greater optimism, lower scores indicating neutrality). A sample positively worded question is, “In uncertain times, I usually expect the best.” The pessimism subscale was the sum of responses to the three negatively worded questions to yield a total score ranging from 0 to 12 (with higher scores indicating greater pessimism and lower scores indicating neutrality). A sample negatively worded question is, “If something can go wrong for me, it will.” Both of these subscales were treated as continuous measures.

Assessments and Other Outcome Measures

Nurse-recruiters collected information on patients’ sociodemographic characteristics and conducted a detailed medical chart review. At baseline, the Perceived Social Support Scale, with higher scores indicating greater support (31), was administered to assess social support, and adherence to physician advice was assessed with the Ziegelstein Healthy Lifestyle Questionnaire (32). Blinded telephone assessors also administered the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (33) to determine mental (Mental Health Composite Score) and physical (Physical Health Composite Score) HRQoL, the 12-item Duke Activity Status Index (34) to determine disease-specific physical functioning, the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders anxiety module to determine the presence of an anxiety disorder (35), and the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRS-D) (36) to track mood symptoms at 2 weeks (baseline) and at 2, 4, and 8 months after hospital discharge.

We defined response to treatment of depression as achieving at least 50% improvement in HRS-D score at 8 months compared to baseline. Eight-month hospitalization was adjudicated by a physician committee. Each hospitalization event was classified by blinded dual-physician review process regarding the reason for hospitalization (e.g., cardiac or noncardiac) (24).

Randomization Procedure

After completion of the 2-week postdischarge assessment and confirmation of protocol eligibility, depressed subjects were randomized either to the collaborative care intervention or to their physicians’ usual care (UC) in a 1:1 ratio.

Usual Care

For ethical reasons (37), we informed UC patients of their depression status, as well as their primary care physicians (PCPs). UC participants received treatment as usual from their clinical health care providers without additional treatment from the research study team, unless we detected suicidality on a follow-up assessment.

Nature of Collaborative Care Intervention

Initial Telephone Contact

A nurse care manager telephoned patients randomized to the collaborative care intervention and educated them about the effect of depression on cardiac health and presented them with different treatment options. These included a) a workbook to enhance the patient's ability to self-care for depression, b) antidepressant pharmacotherapy prescribed by the PCP, c) “watchful waiting” for mildly elevated mood symptoms, and d) referral to a local mental health specialist.

Case Review

At weekly case review meetings, the clinical team (study psychiatrist and internist) formulated treatment recommendations consistent with the patient's needs, current preferences, and insurance coverage. The recommendations were then conveyed to the patient and his/her physician.

Antidepressant Pharmacotherapy

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can be safely prescribed to cardiac patients (38,39), and none have superior efficacy in treatment-naive patients (40,41). For those lacking a history of previous SSRI use or brand preference, we typically recommended citalopram because it has limited drug interactions with other medications, requires few dosage adjustments, and is available in generic form. For patients with depression already using an SSRI, we advised a dosage increase or a switch to another SSRI if they were taking the maximum amount. PCPs had to approve and prescribe all adjustments to their patients’ pharmacotherapy.

Mental Health Referral

Referral to a mental health specialist was advised for patients displaying a poor treatment response, severe psychopathology, complex psychosocial problems, and for those expressing this treatment preference.

Follow-Up

Care manager telephone contacts of 15 to 45 minutes were conducted every other week during the immediate phase (2–4 months) and diminished in frequency as the patients’ conditions improved.

Analyses

We used χ2 analyses and t tests to determine unadjusted associations between optimism/pessimism (i.e., full LOT-R scores) and sociodemographic characteristics, cardiac risk factors, HRQoL, mental health, and adherence to physician's advice in the full sample, the depressed cohort, and the nondepressed cohort. We used logistic regression models to assess the unadjusted and adjusted associations of trait optimism/pessimism with improvement in mood symptoms among depressed patients randomized to treatment, and Cox proportional hazard models to assess unadjusted and adjusted associations of trait optimism/pessimism with post-CABG rehospitalization. Analyses were conducted in the full sample, depressed, and nondepressed participants. Baseline depression severity was included as a covariate in all adjusted analyses. Separate analyses treated the LOT-R score as a) a continuous variable and b) compared highest versus lowest quartiles of LOT-R scores (i.e., optimists versus pessimists) to increase the clinical relevance of results. We used the Holm test to address the issue of multiple comparisons (42).

We repeated the analyses for response to treatment of depression in patients randomized to treatment (n = 284) and with post-CABG rehospitalization in the full sample (n = 430) using the optimism and pessimism subscales. All subscale analyses include both optimism and pessimism subscales, such that results for each subscale (i.e., optimism) control for the other subscale (i.e., pessimism). The Spearman correlation coefficients between the subscales themselves, each subscale and the HRS-D, and the full LOT-R and the HRS-D were also calculated.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

LOT-R Full-Scale Analyses

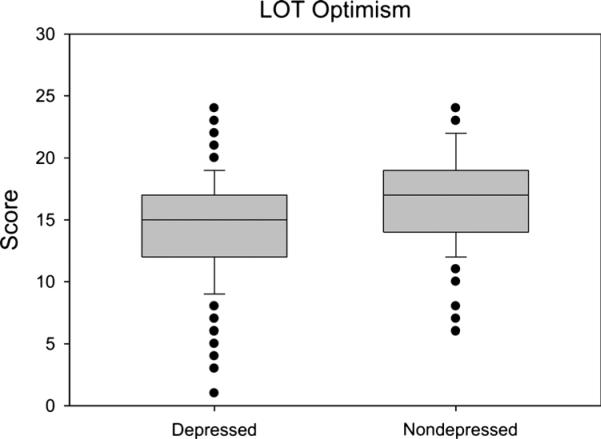

The distribution of LOT-R full-scale scores for depressed (n = 284) and nondepressed (n = 146) patients is shown in Figure 1. Scores were lower among depressed patients (M [standard deviation {SD}] = 14.4 [4.2]) compared with non-depressed patients (M [SD] = 16.9 [3.7], p < .001). Cronbach α for the full LOT-R in this sample was 0.72. The LOT-R score was modestly correlated with depression (HRS-D) in the full cohort (r = –0.34, p < .001) and the depressed cohort (r = –0.25, p < .001) but not in the nondepressed cohort (r = –0.07, p = .41). The LOT-R was also correlated with the cognitive and somatic subscales of HRS-D in the full sample (r = –0.29, p < .001 and r = –0.24, p < .001, respectively) but in the depressed sample only the correlation with the cognitive subscale was significant (r = –0.18, p = .003 and r = –0.075, p = .21).

Figure 1.

Distribution of LOT-R full-scale scores among depressed (n = 284) and nondepressed (n = 146) patients.

In the full sample of 430 patients, the M (SD) LOT-R score was 15.2 (4.2), with a minimum to maximum observed score of 1 to 24. Of these patients, 130 (30%) were classified as pessimists and 82 (19%) were classified as optimists based on the sample-specific distribution of the LOT-R (Table 1). Compared with pessimists, optimists were more educated (p = .03), were physically active (p = .02), had higher mental HRQoL (p < .001), had lower mean HRS-D scores (p < .001), and were less likely to have anxiety at baseline (p < .001). Optimists also reported higher perceived social support (p < .001) and greater adherence to physician advice (p = .01) than pessimists.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of All Post-CABG Study Patients (n = 430)a

| Quartile 1 Pessimists (n = 130, 30%) | Quartile 2 (n = 121, 28%) | Quartile 3 (n = 97, 23%) | Quartile 4 Optimists (n = 82, 19%) | pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 63 (11) | 66 (10) | 65 (11) | 66 (10) | .21 |

| Sex, n (%) | .74 | ||||

| Male | 75 (58) | 73 (60) | 63 (65) | 49 (60) | |

| White, n (%) | 113 (87) | 102 (84) | 87 (90) | 73 (89) | .71 |

| Greater than high school education, n (%) | 61 (47) | 64 (53) | 59 (61) | 54 (66) | .03 |

| Marital status, n (%) | .08 | ||||

| Single | 16 (12) | 8 (7) | 5 (5) | 4 (5) | |

| Married | 82 (63) | 77 (64) | 71 (73) | 64 (78) | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 32 (25) | 36 (30) | 21 (22) | 14 (17) | |

| Working, n (%) | 72 (36) | 62 (32) | 50 (34) | 46 (35) | .85 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 107 (82) | 106 (88) | 82 (85) | 62 (76) | .16 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 59 (45) | 48 (40) | 43 (44) | 29 (35) | .46 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 104 (80) | 99 (82) | 77 (79) | 63 (77) | .86 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 27 (21) | 20 (17) | 14 (14) | 11 (13) | .47 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 54 (42) | 58 (48) | 45 (46) | 40 (49) | .69 |

| HRS-D, M (SD) | 15 (9) | 12 (8) | 11 (8) | 8 (7) | <.001 |

| PRIME-MD anxiety | 42 (32) | 20 (17) | 15 (16) | 8 (10) | <.001 |

| Duke Activity Status Index, M (SD) | 8 (7) | 9 (8) | 10 (7) | 11 (7) | .02 |

| SF-36v2 MCS, M (SD) | 43 (14) | 50 (13) | 51 (12) | 55 (10) | <.001 |

| SF-36v2 PCS, M (SD) | 32 (7) | 32 (8) | 33 (8) | 35 (8) | .05 |

| PSSS, M (SD) | 67 (13) | 70 (12) | 73 (10) | 74 (10) | <.001 |

| Adherence to medical advice, n (%) reporting adherence | 74 (57) | 84 (70) | 71 (74) | 63 (77) | .01 |

CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; HRS-D = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; PRIME-MD = Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders; SF-36v2 = 36-item Short-Form Health Survey; MCS = Mental Health Composite Score; PCS = Physical Health Composite Score; PSSS = Perceived Social Support Scale.

Quartile ranges for LOT-R scores: Quartile 1 (pessimists) = from 0 to 13, Quartile 2 = between 14 and 16, Quartile 3 = between 17 and 18, and Quartile 4 (optimists) = 19 and higher. Note that sample-specific quartiles were calculated for depressed and nondepressed samples and are reported in the text.

p values are from χ2 tests (categorical variables) or t tests (continuous variables) of optimists versus pessimists (Quartile 4 versus Quartile 1).

In the depressed cohort (n = 284), 89 (31%) were classified as pessimists and 65 (23%) were classified as optimists based on the sample-specific distribution of the LOT-R. Among depressed patients, compared with pessimists, optimists were older (M [SD] = 65 [11] versus 62 [11], p = .04), more educated (69% versus 47% reporting greater than high school education, p = .006), had higher mental HRQoL (M [SD] = 47 [10] versus 37 [10], p < .001), greater social support (M [SD] = 71 [11] versus 66 [12], p = .008), and greater adherence (68% versus 47%, p = .01). Optimists were less likely to have baseline anxiety (18% versus 43%, p = .002) and had lower M (SD) baseline HRS-D scores (15 [6] versus 18 [7], p = .001). In the nondepressed cohort (n = 146), 25% were classified as pessimists and 22% were classified as optimists. Among nondepressed patients, compared with pessimists, optimists were more likely to be white (88% versus 65%, p = .03) and less likely to be married (6% versus 11%, p = .008) and to have diabetes (25% versus 57%, p = .008). These sample-specific baseline associations were included in all subsequent adjusted analyses.

LOT-R Subscale Analyses

The M (SD) optimism subscale score was 11 (2), with a minimum to maximum observed score of 4 to 12, whereas the M (SD) pessimism subscale score was 8 (3), with a minimum to maximum observed score of 3 to 12. In a factor analysis, two main factors emerged, with the three positively worded questions (i.e., optimism subscale) and the three negatively worded questions (i.e., pessimism subscale) loading onto separate factors. Together, these factors explain 63% of the variance observed. Analyses using these optimism and pessimism subscales, respectively, are presented separately here. Cronbach α for the optimism subscale was 0.59 and that for the pessimism subscale was 0.74. In the full sample, both the optimism (r = –0.35, p < .001) and the pessimism (r = 0.24, p < .001) subscales were moderately correlated with HRS-D scores and with each other (r = –0.37, p < .001).

Response to Treatment Among Depressed Patients

LOT-R Full-Scale Analyses

Depressed optimists were more likely than depressed pessimists to achieve a response to treatment of depression: M (SD) 8-month HRS-D scores were 8 (6) for optimists and 13 (8) for pessimists (p < .001).

After adjustment for intervention type, education level, physical functioning, perceived social support, mental HRQoL, and baseline depression severity, optimists overall were more than three times more likely than pessimists to respond to treatment of depression (p = .01; Table 2). In sex-stratified adjusted analyses, the point estimate appeared larger for men (odds ratio [OR] = 6.31, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.63–24.48, p = .008) than for women (OR = 2.21, 95% CI = 0.55–8.85, p = .26), but statistical power was limited, and the interaction term for optimism/pessimism and sex was not significant (p = .29).

TABLE 2.

Response to Treatment of Depression Among Optimistic Versus Pessimistic Depressed Patients: LOT-R Full-Scale Analysesa,b,c,d

| Response to Treatment | Optimists Versus Pessimists, OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Full samplec,f | ||

| Unadjusted | 3.81 (1.93–7.53) | <.001 |

| Adjusted | 3.02 (1.28–7.13) | .01 |

| Usual care armd,f | ||

| Unadjusted | 5.60 (1.78–17.57) | .003 |

| Adjusted | 5.70 (1.53–21.33) | .01 |

| Collaborative care arme,f | ||

| Unadjusted | 2.77 (1.10–6.95) | .03 |

| Adjusted | 1.60 (0.47–5.44) | .46 |

LOT-R = Life Orientation Test – Revised; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; HRS-D = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; PRIME-MD = Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders; HRQoL = health-related quality of life.

Middle quartiles of LOT-R full-scale score excluded (only lower quartile “pessimists” and upper quartile “optimists” are shown). Pessimists are the reference group for all analyses

Response to treatment of depression defined as 50% or higher decline in HRS-D score from baseline to 8 months of follow-up.

In the full sample, there are 154 total (89 pessimists and 65 optimists).

In the usual care sample, there are 75 total (48 pessimists and 27 optimists).

In the collaborative care intervention sample, there are 79 total (41 pessimists and 38 optimists).

Adjusted analyses in the full sample control for intervention type (collaborative care versus usual care), age, education level, baseline level of depression on HRS-D, PRIME-MD anxiety, mental HRQoL, perceived social support, and adherence to medical advice. Intervention-stratified adjusted analyses control for all of these except intervention type.

Optimistic depressed patients randomized to their physicians’ UC were more than five times as likely as pessimists to respond to treatment (p = .01; Table 2). Among optimistic depressed patients randomized to intervention, odds of treatment response tended to be 60% higher than among pessimists (Table 2), although results were not statistically significant in this smaller treatment group. In adjusted analyses, each 1-point increase on the LOT-R was associated with higher odds of response to treatment of depression: both arms combined (OR = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.04–1.21, p = .002), UC arm (OR = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.05–1.35, p = .005), and intervention arm (OR = 1.09, 95% CI = 0.99–1.20, p = .07).

LOT-R Subscale Analyses

Among the 284 depressed patients, the optimism subscale was independently related to response to treatment of depression after adjustment for intervention type, age, education, baseline severity of depression, anxiety, mental HRQoL, perceived social support, and self-reported adherence to medical advice. Findings for optimism remained unchanged after adjusting for degree of pessimism. Each 1-point increase on the optimism subscale (i.e., higher optimism) was associated with 15% higher odds of response to treatment of depression (OR = 1.15, 95% CI = 1.01–1.32, p = .04). Every 1-point increase on the pessimism subscale (i.e., higher pessimism) tended to be associated with a 9% lower odds of response to treatment, but this did not remain statistically significant after adjustment (OR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.82–1.01, p = .08).

Rehospitalization After CABG

LOT-R Full-Scale Analyses

During follow-up, there were 197 hospitalizations (148 in the depressed group, 49 in the nondepressed group) (23). Table 3 shows the risk of rehospitalization by 8 months for optimists versus pessimists in the full sample as stratified by depression status. In the full sample, compared with pessimists, the risk of rehospitalization was 46% lower among optimists. Examination of the point estimates for optimists versus pessimists in the depressed (17% lower risk) and nondepressed (65% lower risk) samples suggests that this effect is driven by lower hospitalization risk in the nondepressed group, although statistical power was limited in these stratified analyses. When the LOT-R full scale was treated as a continuous measure in the full sample, each 1-point increase (i.e., higher optimism/lower pessimism) was associated with a 5% lower risk of rehospitalization (OR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.91–0.99, p = .04).

TABLE 3.

Cox Proportional Hazard Models for 8 Months of Rehospitalization: LOT-R Full-Scale Analyses

| Optimists Versus Pessimists, HR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Full samplea (n = 430) | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.56 (0.33–0.94) | .03 |

| Adjusted | 0.54 (0.32–0.93) | .03 |

| Depressed groupb (n = 284) | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.74 (0.41–1.33) | .31 |

| Adjusted | 0.83 (0.44–1.58) | .58 |

| Nondepressed groupc (n = 146) | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.27 (0.09–0.81) | .02 |

| Adjusted | 0.35 (0.11–1.13) | .08 |

LOT-R = Life Orientation Test – Revised; HR = hazards ratio; CI = confidence interval; HRS-D = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; PRIME-MD = Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders; HRQoL = health-related quality of life.

Adjusted analyses for the full sample (depressed and nondepressed) control for education level, baseline level of depression on HRS-D, PRIME-MD anxiety, physical activity, mental HRQoL, physical HRQoL, perceived social support, and adherence to medical advice.

Adjusted analyses for the depressed group control for intervention type (collaborative care versus usual care), age, education level, baseline level of depression on HRS-D, PRIME-MD anxiety, mental HRQoL, perceived social support, and adherence to medical advice.

Adjusted analyses for the nondepressed group control for race, marital status, and diabetes status.

LOT-R Subscale Analyses

In the adjusted analyses in the full sample, the optimism subscale was negatively associated with the risk of all-cause rehospitalization: for each 1-point increase (i.e., higher optimism), the risk of rehospitalization was 9% lower (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.83–1.00, p = .048). Similar to the LOT-R full-scale results, the point estimate was larger in the nondepressed group (HR = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.69–1.01, p = .06) than in the depressed group (HR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.84–1.03, p = .15), although statistical power was limited in the stratified analyses. By contrast, rehospitalization risk did not vary by pessimism subscale scores (effect sizes close to 1.00 in all analyses).

DISCUSSION

Among depressed post-CABG patients, those who were most optimistic (versus pessimistic) were more than three times as likely to respond to treatment of depression. Treatment response seemed to be largely driven by the high rates of improvement among depressed optimistic patients randomized to UC, who were under the UC of their PCPs. Results persisted after controlling for a variety of factors that may be related to treatment response for depression. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of improved response to treatment of depression among optimists compared with pessimists. Our findings confirm prior findings and extend our understanding to this clinical population.

By 8 months of follow-up, compared with pessimists, optimists had a lower rehospitalization rate after CABG. Although our study lacked power to definitively address this question in analyses stratified by depression, the point estimate for optimism was larger in the nondepressed group. Our results thus confirm previous work by Scheier et al. (5), who found that among adults who had recently undergone CABG (and who, in contrast to the current sample, were not selected for depression), optimists were rehospitalized at lower rates than pessimists. Larger studies are needed to understand whether optimism is important for rehospitalization in both depressed and nondepressed populations.

Overall, optimists also reported at baseline better mental and physical HRQoL, lower mood symptoms, higher physical activity, increased perceived social support, and increased adherence to physician advice. These findings confirm and extend similar results in a community-dwelling population, where optimists demonstrated globally favorable CVD risk profiles, including lower prevalence of depressive symptoms (1). We further extend this work by examining baseline factors associated with optimism in both depressed and nondepressed adults.

In analyses aimed at disaggregating optimism from pessimism, the LOT-R subscales were not highly correlated, supporting the hypothesis that these traits may contribute independently to outcomes of interest. Consistent with this idea is the finding that only the optimism subscale was independently related to odds of response to treatment of depression (15% higher for each 1-point increase). These results are intriguing because they differ from prior evidence suggesting that pessimism may be the key psychological trait associated with poorer health outcomes, rather than optimism being associated with favorable health outcomes. For example, pessimism has been more robustly linked to biomarkers of inflammation and immunosenescence, as well as to health outcomes such as incident coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality (43–45).

Results of the current study suggest that optimism may be protective among people with mood disorders. Optimism has been linked to reduced incidence of depression among elderly adults (15), and an intervention designed to increase optimism among high-risk adolescents seemed to decrease pessimistic thoughts (46). The current study demonstrates that optimism, when considered as a bipolar construct, is related to higher odds of response to treatment of depression. In addition, when optimism and pessimism are considered as unipolar traits, optimism is independently associated with response to treatment of depression, whereas pessimism is not. The implication of such findings is that optimism seems to be clinically relevant as a trait, even among depressed individuals. Studies of future interventions designed to alter psychological attitudes should seek to address hypotheses regarding increasing optimistic attitudes (in addition to decreasing pessimistic ones on the basis of previous research). Additional research is also needed to assess the relevance of related psychological factors such as resilience, positive affect, and self-efficacy for depression-related outcomes.

In our sample, it is unclear why optimism did not seem to have the same effect among depressed individuals randomized to the collaborative care intervention (compared with those randomized to UC). It is possible that the strong beneficial effects of this intervention have mitigated the differences between depressed optimists and depressed pessimists in their tendency to respond to treatment of depression. Absolute treatment response rates were high for collaborative care (23), and the relatively small sample in the optimistic collaborative care group may lack power for these post hoc analyses. We encourage future studies to include these scales or similar measures to replicate our findings.

Why should optimistic depressed patients tend to respond to treatment at higher rates than pessimistic depressed patients do? Treatment response is likely to be determined by multiple factors, and possibly related to patient and provider-level factors. Patient-level factors, many of which we were able to correct for, included physical activity and social support. Although speculative, it is possible that depressed optimists (versus depressed pessimists) are better able to control the negative automatic thoughts that are known to contribute to persistent depression (47). As noted, healthy adult optimists (compared with pessimists) tend to cope better with stress (16) and seem to be protected from situational dysphoria (48) and incident depression (15). Thus, the same factors that help optimists avoid depression in the first place may facilitate recovery from post-CABG dysphoria. Pessimists may be subject to the opposite circumstances, which are less favorable from a health perspective.

Strengths of the study include data from a unique clinical population of depressed patients and nondepressed controls undergoing CABG. Validated baseline instruments were used and important factors were assessed, thus allowing for adjustment for a number of variables related to both response to treatment of depression and to rehospitalization after CABG. The study also featured a high follow-up rate and adjudicated outcomes for hospitalization events. Importantly, we included analyses to disaggregate the effects of optimism and pessimism on rates of response to treatment of depression and rehospitalization after CABG. This distinction is important to help guide future studies aimed at determining the extent to which altering attitudes may reduce CVD risk.

Our study is limited by several factors aside from the post hoc nature of the analyses. First, the intervention was not designed specifically to alter optimism or pessimism, and we did not obtain LOT-R scores after treatment. Similarly, it is possible that depression itself could have affected individuals’ responses on the LOT-R, a question that could only be addressed with predepression LOT-R scores. Although the inclusion of optimism and pessimism subscales is a strength, the results are limited by the low α for the optimism subscale. In addition, the study was not designed to assess provider-level (i.e., therapist or PCP) factors that could theoretically have contributed to the differential outcomes observed between optimists and pessimists. For example, more detailed information on interactions between optimists, pessimists, and therapists may have yielded valuable information on mechanisms of response to treatment of depression. Unfortunately, the absolute number of recovering optimistic depressed individuals in the UC and collaborative care groups is too small to permit additional analyses. Finally, we did not follow participants for an extended period to assess the association of optimism and pessimism on long-term outcomes (e.g., mortality).

In conclusion, depressed optimists compared with depressed pessimists are more likely to experience a clinically important improvement in post-CABG mood symptoms. Overall, optimists were less likely to be rehospitalized after CABG surgery. Further research should explore the impact of optimism and pessimism on these and other important long-term post-CABG outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible and facilitated by Grants R01 HL 070000 (PI Dr. Rollman), R24 HL 076852, and R24 HL 076858 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and by a grant from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the NIH, and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research (KL2 RR024154-05, Dr. Tindle).

Glossary

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- CABG

coronary artery bypass graft

- HRQoL

health-related quality of life

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- PHQ-2

2-item Patient Health Questionnaire

- PHQ-9

9-item Patient Health Questionnaire

- LOT-R

Life Orientation Test – Revised

- SF-36

36-item Short-Form Health Survey

- HRS-D

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression

- UC

usual care

- PCP

primary care physician

- SSRI

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

- SD

standard deviation

- CI

confidence interval

- HR

hazard ratio

Footnotes

Patricia R. Houck, MSH, was with the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh when this work was conducted.

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tindle HA, Chang Y-F, Kuller LH, Manson JE, Robinson JG, Rosal MC, Siegle GJ, Matthews KA. Optimism, cynical hostility, and incident coronary heart disease and mortality in the Women's Health Initiative. Circulation. 2009;120:656–62. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.827642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giltay EJ, Kamphuis MH, Kalmijn S, Zitman FG, Kromhout D. Dispositional optimism and the risk of cardiovascular death: the Zutphen Elderly Study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:431–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giltay EJ, Geleijnse JM, Zitman FG, Hoekstra T, Schouten EG. Dispositional optimism and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a prospective cohort of elderly Dutch men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1126–35. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthews KA, Raikkonen K, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Kuller LH. Optimistic attitudes protect against progression of carotid atherosclerosis in healthy middle-aged women. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:640–4. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000139999.99756.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheier MF, Matthews KA, Owens JF, Schulz R, Bridges MW, Magovern GJ, Carver CS. Optimism and rehospitalization after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:829–35. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.8.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pignay-Demaria V, Lesperance F, Demaria RG, Frasure-Smith N, Perrault LP. Depression and anxiety and outcomes of coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:314–21. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04391-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goyal TM, Idler EL, Krause TJ, Contrada RJ. Quality of life following cardiac surgery: impact of the severity and course of depressive symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:759–65. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000174046.40566.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mallik S, Krumholz HM, Lin ZQ, Kasl SV, Mattera JA, Roumains SA, Vaccarino V. Patients with depressive symptoms have lower health status benefits after coronary artery bypass surgery. Circulation. 2005;111:271–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000152102.29293.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doering LV, Moser DK, Lemankiewicz W, Luper C, Khan S. Depression, healing, and recovery from coronary artery bypass surgery. Am J Crit Care. 2005;14:316–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rumsfeld JS, Ho PM, Magid DJ, McCarthy M, Jr, Shroyer ALW, MaWhinney S, Grover FL, Hammermeister KE. Predictors of health-related quality of life after coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1508–13. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blumenthal JA, Lett HS, Babyak MA, White W, Smith PK, Mark DB, Jones R, Mathew JP, Newman MF. Depression as a risk factor for mortality after coronary artery bypass surgery. Lancet. 2003;362:604–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connerney I, Shapiro PA, McLaughlin JS, Bagiella E, Sloan RP. Relation between depression after coronary artery bypass surgery and 12-month outcome: a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;358:1766–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06803-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oxlad M, Stubberfield J, Stuklis R, Edwards J, Wade TD. Psychological risk factors for cardiac-related hospital readmission within 6 months of coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61:775–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burg MM, Benedetto MC, Soufer R. Depressive symptoms and mortality two years after coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) in men. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:508–10. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000077509.39465.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giltay EJ, Zitman FG, Kromhout D. Dispositional optimism and the risk of depressive symptoms during 15 years of follow-up: the Zutphen Elderly Study. J Affect Disord. 2006;91:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheier MF, Weintraub JK, Carver CS. Coping with stress: divergent strategies of optimists and pessimists. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1257–64. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tinker LF, Rosal MC, Young AF, Perri MG, Patterson RE, Van Horn L, Assaf AR, Bowen DJ, Ockene J, Hays J, Wu L. Predictors of dietary change and maintenance in the Women's Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1155–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herzberg PY, Glaesmer H, Hoyer J. Separating optimism and pessimism: a robust psychometric analysis of the revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R). Psychol Assess. 2006;18:433–8. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson-Whelen S, Kim C, MacCallum RC, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Distinguishing optimism from pessimism in older adults: is it more important to be optimistic or not to be pessimistic? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73:1345–53. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.6.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plomin R, Scheier MF, Bergeman CS, Pedersen NL, Nesselroade JR, McClearn GE. Optimism, pessimism and mental health: a twin/adoption analysis. Pers Individ Dif. 1992;13:921–30. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mroczek DK, Spiro A, 3rd, Aldwin CM, Ozer DJ, Bosse R. Construct validation of optimism and pessimism in older men: findings from the normative aging study. Health Psychol. 1993;12:406–9. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.5.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heinonen K, Raikkonen K, Matthews KA, Scheier MF, Raitakari OT, Pulkki L, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L. Socioeconomic status in childhood and adulthood: associations with dispositional optimism and pessimism over a 21-year follow-up. J Pers. 2006;74:1111–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rollman BL, Belnap BH, LeMenager MS, Mazumdar S, Houck PR, Counihan PJ, Kapoor WN, Schulberg HC, Reynolds CF., III Telephone-delivered collaborative care for treating post-CABG depression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:2095–103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rollman BL, Belnap BH, LeMenager MS, Mazumdar S, Schulberg HC, Reynolds CF., III The Bypassing the Blues treatment protocol: stepped collaborative care for treating post-CABG depression. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:217–30. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181970c1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroenke KMD, Spitzer RLMD, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–92. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang EC, editor. Optimism & Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rasmussen HN, Scheier MF, Greenhouse JB. Optimism and physical health: a meta-analytic review. Soc Behav Med. 2009;37:239–56. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9111-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tindle HA, Chang YF, Kuller LH, Manson JE, Robinson JG, Rosal MC, Siegle GJ, Matthews KA. Optimism, cynical hostility, and incident coronary heart disease and mortality in the Women's Health Initiative. Circulation. 2009;120:656–62. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.827642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:1063–78. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blumenthal JA, Burg MM, Barefoot J, Williams RB, Haney T, Zimet G. Social support, type A behavior, and coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 1987;49:331–40. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198707000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ziegelstein RC, Fauerbach JA, Stevens SS, Romanelli J, Richter DP, Bush DE. Patients with depression are less likely to follow recommendations to reduce cardiac risk during recovery from a myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1818–23. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hlatky MA, Boineau RE, Higginbotham MB, Lee KL, Mark DB, Califf RM, Cobb FR, Pryor DB. A brief self-administered questionnaire to determine functional capacity (The Duke Activity Status Index). Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:651–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, Linzer M, deGruy FV, 3rd, Hahn SR, Brody D, Johnson JG. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care. The PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1994;272:1749–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freedland KE, Skala JA, Carney RM, Raczynski JM, Taylor CB, Mendes de Leon CF, Ironson G, Youngblood ME, Rama Krishnan KR, Veith RC. The Depression Interview and Structured Hamilton (DISH): rationale, development, characteristics, and clinical validity. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:897–905. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000028826.64279.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Degenholtz H, Parker LS, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, Post E, Rollman B. Treatment as usual (TAU) control practices in the PROSPECT study: managing the interaction and tension between research design and ethics. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:602–8. doi: 10.1002/gps.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glassman AH, O'Connor CM, Califf RM, Swedberg K, Schwartz P, Bigger JT, Jr, Krishnan KR, van Zyl LT, Swenson JR, Finkel MS, Landau C, Shapiro PA, Pepine CJ, Mardekian J, Harrison WM, Barton D, McLvor M. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. JAMA. 2002;288:701–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mulsant BH, Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds Iii CF, Katz IR, Abrams R, Oslin D, Schulberg HC. Pharmacological treatment of depression in older primary care patients: the PROSPECT algorithm. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:585–92. doi: 10.1002/gps.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whooley M, Simon G. Managing depression in medical outpatients. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1942–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansen R, Gartlehner G, Lohr K, Gaynes B, Carey T. Efficacy and safety of second-generation antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:415–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-6-200509200-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blakesley RE, Mazumdar S, Dew MA, Tang G, Butters MA, Reynolds Iii CF, Houck PR. Comparisons of methods for multiple hypothesis testing in neuropsychological research. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:255–64. doi: 10.1037/a0012850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tindle HACY, Matthews KA, Kuller LH, Manson JE, Tinker LF, Rosa MC, Fugate Woods N, Messina CR, Hunt JR, Coday MC, Freiberg MS, Scheier M. Psychosom Med. Vol. 73. American Psychosomatic Society; Portland, OR: 2010. Is Trait Optimism or Pessimism More Important for Incident CHD and Mortality? pp. A-81–2. [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Donovan A, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Wolkowitz O, Tillie JM, Blackburn E, Epel E. Pessimism correlates with leukocyte telomere shortness and ele vated interleukin-6 in post-menopausal women. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:446–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roy B, Diez-Roux AV, Seeman T, Ranjit N, Shea S, Cushman M. Association of optimism and pessimism with inflammation and hemostasis in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Psychosom Med. 2010;72:134–40. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181cb981b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seligman ME, Castellon C, Cacciola J, Schulman P, Luborsky L, Ollove M, Downing R. Explanatory style change during cognitive therapy for unipolar depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1988;97:13–8. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beck AT. Cognitive models of depression. J Cogn Psychother. 1987;1:5–37. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carver CS, Gaines JG. Optimism, pessimism, and postpartum depression. Cogn Ther Res. 1987;11:449–62. [Google Scholar]