Abstract

Purpose

To explore the multicaregiving roles African American grandmothers assume while self-managing their diabetes.

Design & Methods

This longitudinal, qualitative pilot study explored the challenges of self-managing diabetes among six African-American caregiving grandmothers. Data were collected at 5 times points across 18 months. Content analysis, guided by the Adaptive Leadership framework, was conducted using data matrices to facilitate within-case and cross-case analyses.

Results

Although participants initially stated they cared only for grandchildren, all had additional caregiving responsibilities. Four themes emerged which illustrated how African-American caregiving grandmothers put the care of dependent children, extended family and community before themselves. Using the Adaptive Leadership framework, technical and adaptive challenges arising from multicaregiving were described as barriers to diabetes self-management.

Implications

When assisting these women to self-manage their diabetes, clinicians must assess challenges arising from multicaregiving. This might require developing collaborative work relationships with the client to develop meaningful and attainable goals.

Keywords: Caregiving, grandmothers raising grandchildren, older adults, diabetes, African American, qualitative, longitudinal, multicaregiving, self-management, chronic illness management

Introduction

African-American older adult women are heralded as the backbone of the African-American family and community, adapting to ever-changing societal and psychosocial changes dating back to slavery [1]. These women have multiple roles in the family and community providing care as the matriarch, healer, confidant, advocate, teacher [2] and, increasingly, the primary caregiver of their grandchildren [3]. However, they are also often burdened with chronic illnesses such as diabetes which they must self-manage while serving in these multiple roles. Thus, the pathway to self-management for these women may prove challenging because of multiple caregiving roles [4].

As the 7th leading cause of death [5], the incidence of diabetes has soared to epidemic proportions with diabetes projected to double or triple by 2050 [6]. African-Americans are 77% more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes than non-Hispanic whites [7]. Older African-American women disproportionately suffer from diabetes with 25% over the age of 55 diagnosed with the disease [8].

African-American women have been found to have greater perceived barriers to self-management than men [9]. However, few studies examine why these barriers exist. Several studies have found that the multicaregiving role, including primary caregiving of a grandchild, serves as a barrier to diabetes self-management [10–12]. It is also well documented that primary caregiving of a grandchild may exacerbate and/or impact the self-management of chronic illnesses such as diabetes [13–15]. Primary caregiving in addition to other high-demand roles within the family and community may have serious implications on the self-management of their diabetes. However, few studies have examined how these grandmothers self-manage their diabetes, and no studies were found that examined this phenomenon in the context of multicaregiving. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore the multicaregiving roles these grandmothers assume while self-managing their diabetes.

Theoretical Framework

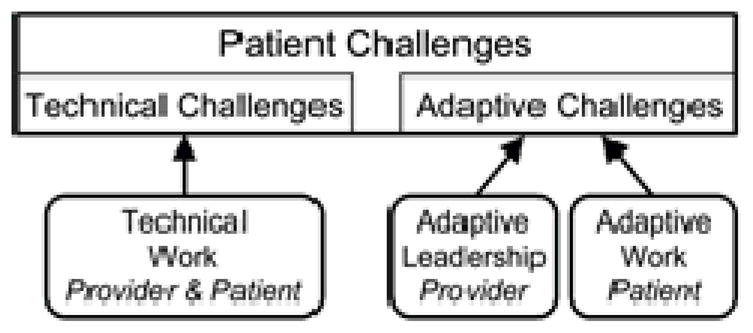

We used the Adaptive Leadership framework as a lens to identify technical and adaptive challenges [16] (see Fig 1). The framework helped us to differentiate technical challenges, those that might be addressed by technical expertise of the providers, from adaptive challenges and the adaptive work that patients must learn and perform for themselves. Technical challenges, such as an elevated Hemoglobin A1c are easily defined with clear cut solutions such as the provider prescribing medications. Adaptive challenges represent the disparity between the capabilities of familiar methods, habits or values and the demands of the present clinical circumstances[16]. Adaptive challenges require that patient adjust to a new situation and to do the work of adapting, learning, and behavior change to address the problem. Adaptive work might involve changing lifestyle to include exercise or practicing stress management; things that only patient can do for themselves. As shown in Figure 1, providers might do technical work in response to identified technical challenges but could engage in adaptive leadership in response to identified adaptive challenges, such as supporting the patients to perform adaptive work.

Figure 1.

Adaptive Leadership Framework

(Adapted from Thygeson, 2010)

Assessing the adaptive challenges of African American caregiving grandmothers with diabetes is the first step in understanding the challenges faced by these grandmothers so that interventions might be developed to support their adaptive work. The multifaceted challenges of caregiving, intertwined with the intricate nature of diabetes self-management, require highly complex and adaptive approaches [17] which are the hallmark of the Adaptive Leadership Framework.

Methodology

This exploratory, longitudinal, qualitative pilot study was part of a larger study examining the trajectory of self-management activities among diabetic African-American primary caregiving grandmothers, Data were collected at 5 time-points across 18 months at approximately 3–4 months intervals. Qualitative interview data were used to explore the multicaregiving roles these grandmothers assumed while managing their diabetes. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the universities of the authors.

Sample and Setting

The inclusion criteria were: 1) African-American females aged 55-years or older 2) primary caregiver of at least one grandchild under age 18, 3) diagnosed with Type-2 diabetes; and, 4) English-speaking. Individuals caring for someone other than grandchildren in the home were excluded during initial screening. Although participants initially stated that they were only caring for their grandchildren, during the course of the interviews we identified that all women had additional caregiving responsibilities.

To ensure comfort and feelings of security, interviews were conducted in the participants’ home or a location of their choosing. Participants selected the time of day for the interviews, and were encouraged by the Principal Investigator to select a time when the child was in school to ensure a quiet environment.

Recruitment

Purposive sampling was used to recruit six diabetic African-American primary caregiving grandmothers living in central North Carolina. The PI used an existing database of grandparents who had consented to be contacted for future studies from a Grandparent Center of a local university. The database indicated if the grandmother had diabetes. Potential participants were telephoned, provided information regarding the study, asked about their interest in participating in the study and screened using the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Flyers were posted throughout the Grandparent Center. We recruited four participants through the Center. Two additional participants were recruited using snowball sampling, in which participants referred others. Once a potential participant expressed interest and met the inclusion criteria, an appointment was scheduled in a location of their choosing to provide additional information regarding the study and, if they remained interested sign a consent form. All participants received a $25 Wal-mart gift card after completing each interview to compensate for their time.

Interviews

The interview guide was developed by the investigators based on a review of literature and previous pilot data. These interviews explored the context in which the participants managed their diabetes while caring for their grandchildren using the global question “Tell me what it is like to manage your diabetes while caring for your grandchildren.” Probes were used to assist the grandmother in elaborating and clarifying statements. The interview guides for the five time points (table 1) were refined throughout the study based on analysis.

Table 1.

| Interview | Activity | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Interview to explore the lived experience of being diabetic and caring for grandchild | Pilot revealed that grandmothers wanted to discuss experiences as a caregiver before they were ready to discuss health. |

| 2 | Self-management interview & survey of self-management activities | Explore lived experience and identify self-management activities. |

| 3 | Same as interview 2 | Same as interview 2 with addition of asking about changes in self-management trajectory. |

| 4 | Same as interviews 3 | Same as interview 3 |

| 5 | Synthesis interview | To explore any final comments from participant. |

Data Collection

The PI conducted all interviews which were digitally recorded and lasted 45–90 minutes. Contextual information and details about the interview experience were documented in field notes. All members of the research team listened to recordings of the interviews and, together adjusted the interview approaches and refined questions to ensure that research questions were addressed. The research team met weekly to discuss coded data and identified areas for follow up in subsequent interviews.

Data preparation

The interviews were transcribed verbatim. The PI reviewed each transcript for accuracy by listening to the recording and prepared them for coding in Atlas TI 6.2 which is a comprehensive network analysis software package used to classify and sort the data.

Data Analysis

Data collection, coding, and analysis occurred simultaneously so that all new text was compared with previously coded text [18]. The members of the research team immersed themselves in the data, coded the first interview for each participant, and identified codes which were refined in weekly meetings. All codes were defined in a code book. Using the code book, the first author coded the remaining interviews. All coding decisions were reviewed by the full research team and coding disagreements were resolved with discussion. After reviewing all codes, categories were established and themes developed. Data from each interview were organized in a matrix for each case to facilitate deep understanding of each case and to facilitate cross case analysis. Raw data quotes were not altered or changed to ensure the integrity of the findings.

Scientific Rigor

Multiple techniques were used to address credibility, dependability confirmability and transferability (Creswell & Clark, 2011). These are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

| Strategies For Assuring Rigor of the Case Study Design |

Confirmability—freedom from unrecognized researcher biases

|

Dependability—the process of the study is consistent across researchers and settings

|

Credibility—authenticity and plausibility, or truth value of the results

|

Transferability—usefulness beyond the individual participants in the study

|

Findings

Although these participants initially stated that they were not caring for anyone other than their grandchildren, they later shared that they provided care to other family members or the community. Four themes emerged from the analysis of the data: Physical Caregiving, Financial Caregiving, Spiritual Caregiving and Community Caregiving.

Physical caregiving

Four of the six participants were involved in physical caregiving to their dependent adult children or extended family members. Three participants assisted with activities of daily living (ADLs) for their adult children that included preparing meals, personal care, and preparing them for bed at night. One participant often put the care of her disabled son before the care of her granddaughter because she felt that if he was well, then the household was well.

“And you know, I make sure that physically, emotionally and all those things are stable for her. She’s as well kept as any young lady could possibly be. And everything she needs in her life is there. But my son is my only child and he is coming through his third recovery from being paralyzed. And, I’m all he’s got. That’s the way I look at it. And I have to make sure everything’s in place for him; if everything’s in place for him and he’s well, he’s not in the hospital, our lives are better on this side.”

The adaptive challenges of physical caregiving impacted her diabetic self-care activities due to fatigue, exhaustion, and time constraints. Many participants stated that they forgot to check their blood sugar because they were too busy or did not take it because they were “too exhausted” to do so. Fatigue and exhaustion also limited their ability to exercise.

Financial Caregiving

The adaptive challenge of financial caregiving was evident among five of the participants which prevented them from diabetes self-care activities. Some expressed difficulty in purchasing glucose testing strips because they had no money left over after paying their own bills as well as providing financially for their extended family. Two participants ensured that her dependent children’s expenses were taken care while they had to “stretch their medication” by taking a pill every other day. Three participants were unable to pay for all of their medications and had to make decisions as to which ones they felt were most important to their health. Another stated that she used a medication that was prescribed daily as a “booster” if her blood sugars were out of hand.

“You know I can’t always afford $30 for a refill. But I know I need that boost every now and then; if my blood sugars get out of control I need the boost of the Actose.”

Two participants sent money monthly to their sons who were incarcerated and one also supported her homeless daughter in addition to caregiving for her grandson. One participant exhausted all of her retirement savings raising her grand and great grandchildren yet she continued to send money to her incarcerated son on a monthly basis. She stated that the mother of the children received state benefits but did not help her support the children.

“I found out that, when I was tryin’ to get food stamps - she was gettin’ $415 dollars’ worth of food stamps and I couldn’t get none. I gotta use my own money for these kids which is hard sometimes because [son] needs his money, too.”

Despite this participant’s limited financial resources due to raising her grandchildren she continued to support her adult son which decreased available monies needed to make healthy food choices and obtain diabetes testing supplies.

Spiritual Caregiving

Spiritual caregiving was noted among four of the six participants. These participants felt they had important roles within their churches and were compelled to remain engaged despite other caregiving responsibilities. All of these participants taught Sunday school at least once per month and were involved in home visits in which they “ministered to the sick” church members which ranged from one – four times per month. These activities created adaptive challenges by increasing fatigue and time constraints and subsequently impacted their ability to perform self-management activities. However they also stated that they enjoyed these responsibilities at their church and would forgo other commitments to remain connected to their church family.

“You know, but I don’t forfeit that [church] - because I need that, you know. That’s where my stability comes from and really the majority of my support - even taking care of him [disabled adult son]-comes from my church family. They take care of me so I take care of them.”

While the church responsibilities limited their time for self-management activities, these activities appeared to serve as a solace for the women.

“I love my church. It gives me piece to be in the house of the Lord. There’s always so much to do at church, ministering to the sick, vacation bible school…stuff like that. I’m doing something all the time. It gets tiring.”

Community Caregiving

All participants were active within their communities. Regardless of the time commitment and fatigue they felt an obligation to the African-American community to “train them in the way they should go”. One participant served as a mentor in the Big Brother/Big Sister program to young girls who were being without their mothers. Another participant provided mentoring to students at a historically black college while working a full-time and four different part-time jobs. Another participant felt it was her obligation as an African-American woman to participate in an upcoming presidential election and therefore recruited others to participate, assist with voter registration, and prepare mailings. She reported that on multiple occasions she forgot to check her blood sugar and ate “fast food” on the go.

“I’m very active in the community and my church and all those things, so there’s a couple days a week that we [grandmother and grandchild] don’t eat right. We eat what we can grab something quick. Usually McDonald’s or something.”

Although this provided a sense of purpose and fruitfulness for this participant, it also served as an adaptive challenge to self-management of her diabetes.

Discussion

This study explores multicaregiving and its impact on self-management of diabetes among African-American caregiving grandmothers and describes the varying degrees and categories of multicaregiving roles and activities for which these women were responsible. The decreased ability to self-manage diabetes due to the multicaregiver role is consistent with the literature [11, 19]. However, this “invisible caregiving” (physical, financial, spiritual and community) was not recognized by them as caregiving despite the burden and stress it often placed upon them.

Moreover, multicaregiving may have a far-reaching impact on self-management of diabetes in the context of primary caregiving of a grandchild. The complexity of advancing age and the multiple caregiving responsibilities in the context of raising their grandchildren creates a multitude of challenges which serve as barriers to diabetes self-management; and, subsequently their overall diabetic health. In addition to their role as parent for their grandchildren they often continued their role as “parent” for their adult children often putting their needs even above those of their grandchildren’s. Continuing to parent adult children while simultaneously parenting their grandchildren might induce conflict, stress and time constraints making it even more problematic to engage in diabetes self-management activities.

Multiple adaptive & challenges of diabetes self-management in the context of multicaregiving serve as barriers to self-management. These challenges must be addressed to assist these women in understanding the importance of caring for themselves. Health care providers must understand that these women often do not believe that they control over their life context but rather react to their obligations which influences how they manage their own health. Attempts at educating these women to say “no” to family and community obligations would have limited benefit because of their cultural belief that they are “mothers of black culture and should be responsible for the world” [20]. However, it might be plausible to assist them in prioritizing obligations to decrease fatigue and time constraints while educating them about available financial and community support so they have viable resources to engage in their self-management activities [11, 12].

This study’s findings also feature the traditional and multiple roles of the African-American woman within their families and communities which are often distorted and unbalanced [11] with blurred personal and political boundaries [20] which influences how they manage their health. Because of these unquestioned and unexamined traditions that have become so deeply rooted in these women, any intervention devoted to improving their diabetes self-management must take into account the importance of blood ties, and community and church membership as extended family and the responsibilities that “families” place on these women.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is the small sample size. However, the study is strengthened by the longitudinal design which established a rapport and trust with the participants allowing them to trust the interview and be more forthright with their experiences. Therefore, this study informs future studies, educational strategies and interventions devoted to improving diabetes self-management among this population.

Conclusion

While “lifestyle change” appears to remain a fundamental part of diabetes education, clinicians should conduct a thorough assessment of these women’s lifestyles and develop a plan that fits into their lifestyle instead of the women changing their lifestyle to fit the diabetes regimen. Goal setting must continue to be a collaborative practice between the client and clinician to ensure that adaptive and technical challenges are examined and resolved so goals are meaningful and attainable. Finally, replicating this study with a larger sample using a mixed methodology may provide further insight into additional challenges surrounding the self-management their diabetes in the context of multicaregiving including serving as the primary caregiver of their grandchildren.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the John A. Hartford, Building Academic Geriatric Nursing Capacity Program and the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Ethnicity, Culture and Health Outcomes Program. The research team used services of the P30 Center, Adaptive Leadership for Cognitive/Affective Symptoms Science in the analysis of this paper (1P30NR014139-01). The authors sincerely thank the women who participated in the study.

Contributor Information

Dana L. Carthron, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Social Medicine.

Donald E. Bailey, Jr., Duke University, School of Nursing.

Ruth A. Anderson, Duke University, School of Nursing.

References

- 1.Woods-Giscombe CL. Superwoman schema: African American women’s views on stress, strength, and health. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(5):668–83. doi: 10.1177/1049732310361892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webel AR, Higgins PA. The relationship between social roles and self-management behavior in women living with HIV/AIDS. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(1):e27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States Census Bureau. 2010 American Community Survey, S1002, Grandparents. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black A, Peacock P. Pleasing the masses: messages for daily life management in African American women’s popular media sources. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(1):144–150. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.167817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Center for Disease Control. Leading causes of death. 2013 [cited 2013 October 30]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/lcod.htm.

- 6.Center for Disease Control. Number of Americans with Diabetes Projected to Double or Triple by 2050. 2010 [cited 2013 October 30]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/media/pressrel/2010/r101022.html.

- 7.National Diabetes Education Program. The facts about diabetes: a leading cause of death in the US. n.d [cited 2013 October 30]; Available from: http://ndep.nih.gov/diabetes-facts/

- 8.Office of Women’s Health. Minority women’s health: diabetes. 2010 [cited 2013 October 30]; Available from: http://womenshealth.gov/minority-health/african-americans/diabetes.html.

- 9.Chlebowy DO, Hood S, LaJoie AS. Gender Differences in Diabetes Self- Management Among African American Adults. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0193945912473370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penckofer S, et al. The Psychological Impact of Living With Diabetes: Women’s Day-to-Day Experiences. The Diabetes Educator. 2007;33(4):680–690. doi: 10.1177/0145721707304079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter-Edwards L, et al. “They care but don’t understand”’: Family support of African American women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educator. 2004;30(3):493–501. doi: 10.1177/014572170403000321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samuel-Hodge CD, et al. Familial roles of older African-American women with type 2 diabetes: testing of a new multiple caregiving measure. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(3):436–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelley SJ, Whitley DM, Campos PE. Psychological distress in African American grandmothers raising grandchildren: the contribution of child behavior problems, physical health, and family resources. Res Nurs Health. 2013;36(4):373–85. doi: 10.1002/nur.21542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carthron DL, et al. “Give me some sugar!” the diabetes self-management activities of African-American primary caregiving grandmothers. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2010;42(3):330–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2010.01336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.del Bene SB. African American grandmother raising grandchildren: a phenomenological perspective of marginalized women. J Gerontol Nurs. 2010;36(8):32–40. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20100330-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heifetz RA, Linsky M, Grashow A. The practice of adaptive leadership: tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world. Cambridge, MA: Haarvard Business Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin C, Sturmberg J. Complex adaptive chronic care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(3):571–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Streubert-Speziale HJ, Carpenter DR. Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative. 5. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samuel-Hodge CD, et al. Influences on day-to-day self-management of type 2 diabetes among African-American women: spirituality, the multi-caregiver role, and other social context factors. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(7):928–933. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott KY. The Habit of Surviving. Random House; New York: 1991. p. 11. [Google Scholar]