Abstract

Aim:

To evaluate and compare the effect of antibacterial intracanal medicaments on inter-appointment flare-up in diabetic patients.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty diabetic patients requiring root canal treatment were assigned into groups I, II, and III. In group I, no intracanal medicament was placed. In groups II and III, calcium hydroxide and triple antibiotic pastes were placed as intracanal medicaments, respectively. Patients were instructed to record their pain on days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 14. Inter-appointment flare-up was evaluated using verbal rating scale (VRS).

Results:

Overall incidence of inter-appointment flare-up among diabetic patients was found to be 16%. In group I, 50% of the patients and in group II, 15% of the patients developed inter-appointment flare-up. However, no patients in group III developed inter-appointment flare-up. The comparison of these results was found to be statistically significant (P = 0.002; χ2 = 12.426). However, with respect to intergroup comparison, only the difference between groups I and III was found to be statistically significant (P = 0.002; χ2 = 12.00).

Conclusions:

Calcium hydroxide and triple antibiotic paste are effective for managing inter-appointment flare-ups in diabetic patients. Triple antibiotic paste is more effective than calcium hydroxide in preventing the occurrence of flare-up in diabetic patients.

Keywords: Calcium hydroxide, diabetes, inter-appointment flare-up, intra-canal medicament, triple antibiotic

INTRODUCTION

Inter-appointment flare-up may be defined as the occurrence of severe pain, swelling, or both, following an endodontic treatment appointment, which requires an unscheduled visit for emergency treatment.[1,2] It is reported that patients with diabetes mellitus are prone to severe endodontic infections and have increased incidence of flare-up.[3] This is attributed to alterations in immune functions and the presence of more virulent microorganisms in root canals of diabetic patients.[4,5,6]

Various intracanal medicaments are advocated to eliminate bacteria and prevent multiplication of bacteria between the appointments.[3] Calcium hydroxide (CH) has been the most commonly used medicament, and its dressing is shown to provide more bacteria-free canals than those devoid of any dressing.[7]

Local application of antibiotics in the root canal has been suggested to overcome the potential risk of adverse systemic effects of antibiotics and as an effective mode for drug delivery in teeth lacking blood supply due to necrotic pulps or pulp-less status.[8] Because root canal infections are polymicrobial consisting of both aerobic and anaerobic bacterial species, single antibiotic may not be effective in canal disinfection. Therefore, combination of antibiotics, mainly consisting of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, and minocycline, referred to as triple antibiotic (TA) paste has been suggested for root canal disinfection.[9,10]

Because diabetic patients are prone to severe endodontic infections and increased flare-up, antibacterial intracanal medicaments such as CH and TA paste may play an important role in reducing the incidence of inter-appointment flare-up in diabetic patients. Few studies have evaluated the role of CH on the incidence of flare-up.[11,12] However, hardly any studies have evaluated the effect of these antibacterial intracanal medicaments on the incidence of flare-up in diabetic patients. Therefore, the present in vivo study was conducted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

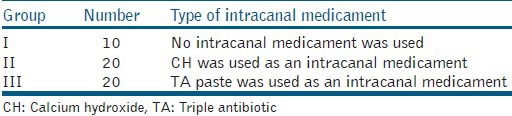

The following study was carried out after obtaining the approval of the institutional ethics committee (Reference no. 09077). Fifty male and female adult patients aged between 18-60 years and having diabetes mellitus and requiring root canal treatment in single rooted anterior and premolar teeth were selected. The selected patients were considered irrespective of type and control status of diabetes, and the selected tooth was considered irrespective of its pulpal, periapical, and periodontal status. However, patients with systemic factors such as pregnancy, immunocompromised status, and tooth-related factors such as root fractures, open apex, intraoral and extraoral swelling, extraoral sinus opening, and need for retreatment were excluded from the study. The selected patients, who signed the informed consent, were randomly assigned into following groups as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Type of study groups and number of diabetic patients

Root canal treatment was initiated under local anesthesia and rubber dam isolation. Working length was established 1 mm from the radiographic apex. The coronal one-third of the canal was enlarged using Gates Glidden drills (Mani, Inc., Tochigi, Japan). The apical portion of the canal was enlarged using K-files (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) to size 3-4 files larger than the initial apical file, and the rest of the canal was prepared using step-back technique. The canals were irrigated copiously with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite (Novo Dental Products Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India), 17% EDTA (B. N. Laboratories, Mangalore, India), normal saline, and 0.2% chlorhexidine (Vishal Dentocare Pvt. Ltd., Ahmedabad, India). The final irrigation was done with normal saline. Following instrumentation and irrigation, canals were dried and treated in the following manner:

Group I: Access opening was restored temporarily with zinc oxide eugenol cement (Dental Products of India, Mumbai, India), without any intracanal medicament.

Group II: CH was placed as an intracanal medicament. A total of 100 mg of CH powder (Dento Kem, Faridabad, India) was dispensed and mixed with one drop of propylene glycol on a clean and dry glass slab to prepare a thick paste-like consistency. This paste was carried into the canal and gently compacted using a finger pluggers, and access opening was restored temporarily with zinc oxide eugenol cement.

Group III: TA paste was used as an intracanal medicament. It was prepared by removing the coating and crushing of antibiotic ciprofloxacin (Ciplox 500 mg, Cipla, India), metronidazole (Metrogyl 400 mg, J. B. Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals Ltd., India), and minocycline (Minoz 100mg, Cipla, India) tablets separately using a mortar and pestle. The crushed powder was passed through a fine sieve to remove heavy filler particles and obtain a fine powder. The ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, and minocycline powders thus obtained were weighed separately and mixed in a 1:3:3 proportions, respectively, to obtain TA mixture. A total of 100 mg of this TA mixture was dispensed and mixed with one drop of propylene glycol to get a thick paste-like consistency. This paste was placed and gently compacted into the canal using a finger plugger, and access opening was restored with zinc oxide eugenol cement. The patients belonging to group II and group III were recalled after 7 days following the first visit to change the intracanal medicament.

All the treated patients were prescribed paracetamol tablets and received a questionnaire to record their pain on days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 14. Inter-appointment flare-up was assessed using verbal rating scale (VRS) using the following criteria:[13,14]

VRS-0 (the treated tooth felt normal)

VRS-1 (the treated tooth was slightly painful for a time, regardless of the duration, but there was no need to take analgesics)

VRS-2 (the treated tooth caused discomfort and/or pain, which was rendered comfortable by taking one tablet of paracetamol)

VRS-3 (the treated tooth caused discomfort and/or pain, which was rendered comfortable by taking two tablets of paracetamol at a 6-h interval)

VRS-4 (the treated tooth caused discomfort and/or pain, which was rendered tolerable by taking two tablets of paracetamol at every 6 h for 3 days)

VRS-5 (severe pain and/or swelling caused by the treated tooth that disturbed normal activity or sleep and paracetamol tablet had little or no effect.)

Cases with VRS 4 and 5 were regarded as inter-appointment flare-up. The results were analyzed using Chi-square test and statistical package Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 16.

RESULTS

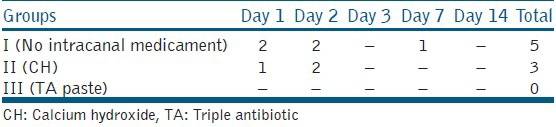

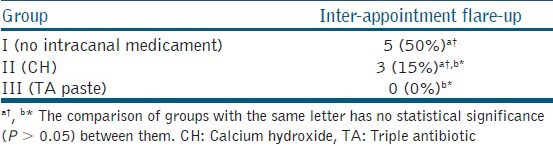

Among the total 50 diabetic patients evaluated, 16% of the patients (8 of 50 patients) developed inter-appointment flare-up. The groups with number of patients who developed inter-appointment flare-up at different time intervals are shown in Table 2. In group I (no intracanal medicament) 50% (5 of 10 patients) of the patients and in group II (CH) 15% (3 of 20 patients) of the patients developed inter-appointment flare-up. However, none of the patients in group III (TA paste) developed inter-appointment flare-up [Table 3].

Table 2.

Incidence of inter-appointment flare-up in diabetic patients at different time intervals

Table 3.

Number and percentage of diabetic patients with inter-appointment flare-up

Although the results were statistically significant (P = 0.002; χ2 = 12.426), only the difference between groups I and III was significant (P = 0.002; χ2 = 12.00). However, the differences between groups I and II (P = 0.07; χ2 = 4.176) and groups II and III (P = 0.23; χ2 = 3.243) were statistically not significant.

DISCUSSION

Pain is inherently subjective and its measurements primarily rely on the verbal report of the patients. Several scales and methods have been used for the assessment of pain after endodontic therapy. Among them, the VRS is considered to be a valid and reliable scale for the measurement of pain.[15] Therefore, VRS was used in this study to evaluate inter-appointment flare-up. The scores of VRS were categorized into six groups (ranging from 0 to 5) based on the need and quantity of analgesic intake for any pain relief. This was done to make the patient understand the pain scale better and make it clinically more relevant.[16]

The recommended retention period for the intracanal medicament is no less than 14 days. However, recontamination of the canal may take place if the medicament is retained for 2 weeks.[17,18] Considering a minimum 1-week retention period, medicaments were changed after 7 days in the current study.

A flare-up is said to be those incidences of either severe pain or swelling in 48 h (2 days) after the initiation of the endodontic procedure without any correlation with the number of visits of endodontic treatment.[19] Furthermore, inflammation is said to take at least 10–14 days to subside.[6,17] Therefore, the incidence of inter-appointment flare-up in the present study was evaluated on days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 14.

In the present study, overall incidence of inter-appointment flare-up in diabetic patients was found to be 16%. A retrospective study that evaluated the effect of diabetes mellitus on the endodontic treatment outcome, using data from an electronic patient record, showed an incidence of flare-up of 4.8 and 2.3% in diabetic and non-diabetic patients, respectively. Though it was not statistically significant, it was said that diabetic patients had twice as many flare-ups than nondiabetic patients.[6] The increased incidence of flare-up in diabetic patients could be a result of the alterations in immune functions, such as depressed leukocyte adherence, chemotaxis, and phagocytosis, or the presence of more virulent microorganisms in root canals with necrotic pulp of such patients as shown by various studies.[4,5] A study by Fouad et al., showed a positive association between the presence of diabetes and certain virulent root canal bacteria.[4]

In the present study, highest incidence of inter-appointment flare-up was found in no intracanal medicament group, as half the patients in it developed the flare-up. This signifies that diabetic patients undergoing endodontic therapy without medicaments between the visits are more prone to flare-ups.

In comparison with no intracanal medicament group, though statistically insignificant, fewer diabetic patients in CH group developed inter-appointment flare-up. This could be attributed to the chemical, physical, and antimicrobial effects of CH. CH due to the release and diffusion of its hydroxyl (OH−) ions leads to a highly alkaline environment, which is not conducive to the survival of microorganisms in the root canal.[20]

In contrast, none of the diabetic patients with TA paste developed any inter-appointment flare-up. This finding was statistically significant in comparison with no intracanal medicament group and could be attributed to the combined spectrum of antimicrobial activity and synergetic or additive actions of antibiotics ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, and minocycline found in TA paste. Individually, ciprofloxacin has broad spectrum activity and acts against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria by inactivating enzymes and inhibiting cell division.[21] Metronidazole is effective against obligate anaerobes, which are common in the deep dentin of infected root canals and acts by disrupting bacterial DNA.[21] Minocycline is a broad-spectrum tetracycline antibiotic and acts by inhibiting protein synthesis and inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase enzyme.[21] Combination of these three antibiotics overcomes bacterial resistance and achieves higher antimicrobial action.[9] Previous studies have shown favorable results when antibiotic mixture of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, and minocycline has been used as topical root canal agents.[9,10,22] The absence of inter-appointment flare-up with TA paste can also be attributed to the anti-inflammatory property of antibiotic minocycline.[23] However, TA paste can have few drawbacks. It is shown to be most cytotoxic to human periodontal ligament fibroblasts and cause persistent and exacerbated inflammatory reaction in mouse subcutaneous connective tissue.[24,25] This might be potentially significant in diabetic patients due to their immunocompromised status as any overextrusion of TA paste can become counterproductive. Additionally, TA paste is said to cause most severe discoloration of the tooth due to minocycline component.[26]

In the current study, though no statistical significance was found between CH and TA paste groups, few patients in CH group had developed inter-appointment flare-up when compared with none in TA paste group. Therefore, it may be clinically relevant to consider that CH may not be as effective intracanal medicament as TA paste. It is suggested that CH may fail to exert its beneficial effects due to factors such as increased bacterial adhesion to dentin, buffering capacity of dentine, presence of biofilm, and necrotic tissue. Further, certain bacteria like Enterococcus faecalis and opportunistic infection causing organisms such as Candida, which are commonly found in diabetic patients, are found to be highly resistant to CH.[20,27] Recent studies also have supported this and showed that CH has limited efficacy against the above organisms and lesser antimicrobial activity when compared with other intracanal medicaments tested in the studies.[28,29]

CONCLUSION

CH and TA paste are effective for managing inter-appointment flare-up in diabetic patients. However, TA paste is more effective than CH in preventing the occurrence of flare-up in diabetic patients. However, more controlled studies are required for further clinical validation of the findings pertaining to the present study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Ramya Shenoy (Associate Professor, Department of Public Health Dentistry, MCODS [Manipal University], Mangalore) for her contribution in carrying out the statistical analysis of the study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Walton RE, Fouad A. Endodontic interappointment flare-ups: A prospective study of incidence and related factors. J Endod. 1992;18:172–7. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81413-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siqueira JF., Jr Microbial causes of endodontic flare-ups. Int Endod J. 2003;36:453–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2003.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Athanassiadis B, Abbott PV, Walsh LJ. The use of calcium hydroxide, antibiotics and biocides as antimicrobial medicaments in endodontics. Aust Dent J. 2007;52:S64–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2007.tb00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fouad AF. Diabetes mellitus as a modulating factor of endodontic infections. J Dent Educ. 2003;67:459–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delamaire M, Maugendre D, Moreno M, Le Goff MC, Allannic H, Genetet B. Impaired leucocyte functions in diabetic patients. Diabet Med. 1997;14:29–34. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199701)14:1<29::AID-DIA300>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fouad AF, Burleson J. The effect of diabetes mellitus on endodontic treatment outcome. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:43–51. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shuping GB, Orstavik D, Sigurdsson A, Trope M. Reduction of intracanal bacteria using nickel-titanium rotary instrumentation and various medications. J Endod. 2000;26:751–5. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200012000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohammadi Z, Abbott PV. On the local applications of antibiotics and antibiotic-based agents in endodontics and dental traumatology. Int Endod J. 2009;42:555–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2009.01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoshino E, Kurihara-Ando N, Sato I, Uematsu H, Sato M, Kota K, et al. In vitro antibacterial susceptibility of bacteria taken from infected root dentine to a mixture of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole and minocycline. Int Endod J. 1996;29:125–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1996.tb01173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Windley W, 3rd, Teixeira F, Levin L, Sigurdsson A, Trope M. Disinfection of immature teeth with a triple antibiotic paste. J Endod. 2005;31:439–43. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000148143.80283.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trope M. Relationship of intracanal medicaments to endodontic flare-ups. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1990;6:226–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1990.tb00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghoddusi J, Javidi M, Zarrabi MH, Bagheri H. Flare-ups incidence and severity after using calcium hydroxide as intracanal dressing. N Y State Dent J. 2006;72:24–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Andrade Risso P, da Cunha AJ, de Araujo MC, Luiz RR. Postoperative pain and associated factors in adolescent patients undergoing two-visit root canal therapy. Aust Endod J. 2009;35:89–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2008.00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Negrish AR, Habahbeh R. Flare up rate related to root canal treatment of asymptomatic pulpally necrotic central incisor teeth in patients attending a military hospital. J Dent. 2006;34:635–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lund I, Lundeberg T, Sandberg L, Budh CN, Kowalski J, Svensson E. Lack of interchangeability between visual analogue and verbal rating pain scales: A cross sectional description of pain etiology groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bodian CA, Freedman G, Hossain S, Eisenkraft JB, Beilin Y. The visual analog scale for pain: Clinical significance in postoperative patients. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:1356–61. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200112000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abbott PV. Medicaments: Aids to success in endodontics. Part 2. Clinical recommendations. Aust Dent J. 1990;35:491–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1990.tb04678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomes BP, Sato E, Ferraz CC, Teixeira FB, Zaia AA, Souza-Filho FJ. Evaluation of time required for recontamination of coronally sealed canals medicated with calcium hydroxide and chlorhexidine. Int Endod J. 2003;36:604–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2003.00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pickenpaugh L, Reader A, Beck M, Meyers WJ, Peterson LJ. Effect of prophylactic amoxicillin on endodontic flare-up in asymptomatic, necrotic teeth. J Endod. 2001;27:53–6. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200101000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siqueira JF, Jr, Lopes HP. Mechanisms of antimicrobial activity of calcium hydroxide: A critical review. Int Endod J. 1999;32:361–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.1999.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL. 11th ed. New York: McGraw Hill companies; 2006. Goodman and Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics; pp. 1111–26. (1049-72). 1182-7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alam T, Nakazawa F, Nakajo K, Uematsu H, Hoshino E. Susceptibility of Enterococcus faecalis to a combination of antibacterial drugs (3 mix) in vitro. J Oral Biosci. 2005;47:315–20. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunston CR, Griffiths HR, Lambert PA, Staddon S, Vernallis AB. Proteomic analysis of the anti-inflammatory action of minocycline. Proteomics. 2011;11:42–51. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yadlapati M, Souza LC, Dorn S, Garlet GP, Letra A, Silva RM. Deleterious effect of triple antibiotic paste on human periodontal ligament fibroblasts. Int Endod J. 2013 doi: 10.1111/iej.12216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pereira MS, Rossi MA, Cardoso CR, da Silva JS, da Silva LA, Kuga MC, et al. Cellular and molecular tissue response to triple antibiotic intracanal dressing. J Endod. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lenherr P, Allgayer N, Weiger R, Filippi A, Attin T, Krastl G. Tooth discoloration induced by endodontic materials: A laboratory study. Int Endod J. 2012;45:942–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2012.02053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waltimo TM, Sirén EK, Orstavik D, Haapasalo MO. Susceptibility of oral Candida species to calcium hydroxide in vitro. Int Endod J. 1999;32:94–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.1999.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinha N, Patil S, Dodwad PK, Patil AC, Singh B. Evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy of calcium hydroxide paste, chlorhexidine gel, and a combination of both as intracanal medicament: An in vivo comparative study. J Conserv Dent. 2013;16:65–70. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.105302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eswar K, Venkateshbabu N, Rajeswari K, Kandaswamy D. Dentinal tubule disinfection with 2% chlorhexidine, garlic extract, and calcium hydroxide against Enterococcus faecalis by using real-time polymerase chain reaction: In vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2013;16:194–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.111312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]