Abstract

Understanding forgetting from working memory, the memory used in ongoing cognitive processing, is critical to understanding human cognition. In the last decade a number of conflicting findings have been reported regarding the role of time in forgetting from working memory. This has led to a debate concerning whether longer retention intervals necessarily result in more forgetting. An obstacle to directly comparing conflicting reports is a divergence in methodology across studies. Studies which find no forgetting as a function of retention-interval duration tend to use sequential presentation of memory items, while studies which find forgetting as a function of retention-interval duration tend to use simultaneous presentation of memory items. Here, we manipulate the duration of retention and the presentation method of memory items, presenting items either sequentially or simultaneously. We find that these differing presentation methods can lead to different rates of forgetting because they tend to differ in the time available for consolidation into working memory. The experiments detailed here show that equating the time available for working memory consolidation equates the rates of forgetting across presentation methods. We discuss the meaning of this finding in the interpretation of previous forgetting studies and in the construction of working memory models.

Keywords: Short-term Memory, Working Memory, Forgetting, Decay, Consolidation

Forgetting of information crucial to performance in everyday tasks is ubiquitous to the human experience. Surprisingly, more than half a century of research on forgetting has not produced a consensus as to the causes of forgetting over the short-term. Perhaps the largest point of dispute is about whether the passage of time is responsible for forgetting from working memory (Barrouillet, Bernardin, & Camos, 2004; Cowan, 1988, 1995, Ricker & Cowan, 2010), or if interference alone can account for all forgetting (Berman, Jonides, & Lewis, 2009; Farrell, 2012; Lewandowsky, Duncan, & Brown, 2004; Oberauer & Kliegl, 2006; Oberauer & Lewandowsky, 2008; White, 2012). To be clear, by working memory we mean memory traces which can be immediately accessed and used to perform a cognitive task. Even among authors who propose that time does contribute to forgetting, some argue that the length of the retention interval contributes to forgetting (Ricker & Cowan, 2010; McKeown & Mercer, 2012), while others argue that, in mature individuals, decay is counteracted by processes that refresh the representation, thereby preventing duration-based forgetting (Barrouillet et al. 2004).

The presence or absence of forgetting based on the passage of time is in some ways the most basic question that can be asked about working memory. The proposition that there is a short-term memory faculty separate from long-term memory often depends on the existence of forgetting over time, as in the notion of a temporarily activated portion of long-term memory (Cowan, 1988, 1995; Barrouillet et al., 2004; Barrouillet, Portrat, & Camos, 2011). Forgetting over time is also one of the most problematic to investigate because of confounds that occur with the passage of time, such as increased interference with longer retention intervals or the presence of verbal rehearsal during retention. Despite the difficulty, some well-designed investigations in recent years have been able to test the issue, apparently with few, if any, identifiable confounds. In these studies, though, some find no time-based forgetting (Lewandowsky et al., 2004; Lewandowsky, Oberauer, & Brown, 2009; Oberauer & Lewandowsky, 2008), others find an effect of the relative amount of occupied time but no effect of the length of the retention interval (Barrouillet et al., 2004, 2011; Barrouillet, De Paepe, & Langerock, 2012), and yet others find time-based forgetting based on the length of the retention interval (McKeown & Mercer, 2012; Morey & Bieler, 2012; Ricker & Cowan, 2010, Woodman, Vogel & Luck, 2012, Zhang & Luck, 2009).

We wished to bring some order to these diverse results by exploring what factors may determine when there is or is not an effect of the length of the retention interval. One of the largest methodological differences between those that generally find time-based effects of retention interval duration and those that generally do not is the method of item presentation. Ricker and Cowan (2010), Morey and Bieler (2012), Woodman et al. (2012), and Zhang and Luck (2009) all used brief simultaneous presentation of items and found an effect of retention interval duration on memory performance, whereas those using the complex span task and serial recall paradigms, which have a longer sequential item presentation method, generally have found no effect of retention length (i.e., Barrouillet et al., 2004; Lewandowsky et al., 2004). Here we detail four experiments in which various factors were held constant while we varied both the retention interval duration and the method of presentation, in which the items were shown either sequentially or simultaneously.

In previous research, most sequential presentation studies have used verbal memoranda, such as words, letters, or digits, whereas many recent simultaneous presentation studies have used non-verbal items that are difficult to label. This difference, however, does not appear to be driving the differences in forgetting rates across methodologies. For example, Verguawe and colleagues used both visual and verbal items following the sequential method of Barrouillet et al. (2004) and found similar patterns of effects with both presentation modalities (Verguawe, Dewaele, Langerock, & Barrouillet, 2012; Vergauwe, Barrouillet, & Camos, 2009, 2010). Nevertheless, in this study we eliminate any such factor by using the same materials, unfamiliar characters, across simultaneous and sequential presentation methods.

As a preview, Experiments 1 and 2 demonstrate that the simple manipulation of presentation method has a profound effect on forgetting. With basic sequential presentation of items much less forgetting was observed as a function of retention interval duration than was observed under simultaneous item presentation. Experiments 3 and 4 demonstrate the reason for this difference. Studies with sequential presentation tend to have an increased period of working-memory consolidation, which modifies the rate of forgetting. When the time allowed for working-memory consolidation is equated across presentation methods, rates of forgetting become equivalent. This finding has profound implications for the study and modeling of forgetting in working memory.

We hasten to make a distinction between processes we term encoding and consolidation. Encoding is defined here as a phase of stimulus processing establishing the stimulus identity and characteristics, which can be terminated by a pattern mask (for single stimuli see Turvey, 1973; for multi-item arrays see Vogel, Woodman, & Luck, 2006). In contrast, consolidation is further processing that can occur even after a mask, and that helps makes the representation of the stimulus more resistant to forgetting (Jolicouer & Dell’acqua, 1998). Massaro (1975) could have characterized encoding as the formation of synthesized sensory memory and consolidation as the formation of generated abstract memory. Similarly, in a different theoretical framework, Cowan (1988, 1995) could characterize encoding as the use of a brief, literal phase of sensory memory to create the activation of long-term memory features, and could characterize consolidation as the entry of these activated features into the focus of attention, with a concomitant improvement in the representations and their integration. (We later suggest more specific possible mechanisms for this short-term consolidation but do not try to distinguish it empirically from long-term consolidation, a major and difficult future issue for the field.) To anticipate the findings, the time available for consolidation matters for the stability of representations over time, even if the exposure time and the time available for encoding both have been equated across presentation conditions.

Experiment 1

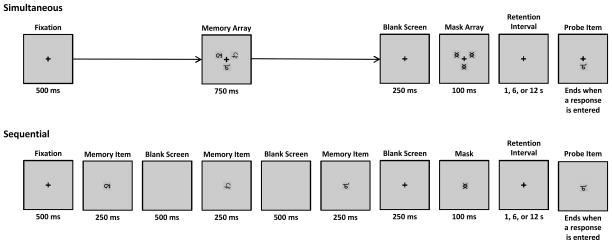

In Experiment 1 participants had to remember 3 unfamiliar characters over a variable retention period. On some trials the items were presented simultaneously, while on other trials the items were presented sequentially (Figure 1). If presentation method plays a role in determining whether or not increased forgetting occurs as the retention interval increases, then we should see more forgetting as a function of time in the simultaneous presentation condition than in the sequential presentation condition.

Figure 1.

An example of a single simultaneous presentation trial, top, and a single seqential presentation trial, bottom, in Experiment 1.

Method

Design

The experiment consisted of the presentation of 3 items that were to be remembered over a variable retention interval. Presentation Method and Retention-Interval Duration were manipulated. Presentation of items was either sequential or simultaneous. Each participant performed the task with both presentation methods and all retention intervals. The presentation method was blocked so that the first half of the experiment consisted entirely of trials of one presentation method and the second half consisted entirely of trials with the other presentation method. Presentation method order was counterbalanced so that half of the participants received the sequential trials first, while the other half received the simultaneous trials first. Retention-Interval Duration for any given trial was randomly chosen from one of three durations (1, 6, or 12s), with the constraint that there were an equal number of trials with each retention interval duration. Following 12 practice trials, there were 108 test trials for each Presentation Method (36 trials for each Retention-Interval Duration).

Participants

Thirty-two college students (28 female, 4 male, ages 18–23) enrolled in introductory psychology at the University of Missouri participated in the experiment in exchange for partial course credit. The participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 counterbalancing orders, with an equal number of participants in each group. All participants were screened to ensure that they did not speak or read any of the languages from which the memory stimuli were taken, and had not lived in any of the countries in which they may have regularly been exposed to the characters used in the experiment.

Materials

The stimuli were presented to participants on standard CRT monitors while seated in a sound attenuated room. Responses were collected by button press on a standard computer keyboard. Participants sat at a comfortable distance from the screen while performing the experiment. The items used as stimuli were black characters presented on a grey background. These items consisted of 231 characters used in written languages other than English and resembling no English letters, English numerals, or other characters likely to be familiar to students attending a university in the rural central United States. These items were used in order to ensure that participants could not easily verbally encode the characters. Ricker, Cowan, & Morey (2010) used a similar item set and demonstrated that verbal recoding of the stimuli did not contribute to memory performance. In the present study, each stimulus subtended roughly 2.3 × 2.3 degrees of visual angle.

Procedure

The sequence of events for an experimental trial is shown graphically in Figure 1. Participants began each trial by pressing the space bar. At the beginning of each trial a fixation cross appeared at the center of the screen and remained on screen throughout the trial, except during sequential item presentation. This fixation cross was alone on screen for 500 ms and was followed by the presentation of the memory-set items. In the simultaneous presentation condition all items were presented together for 750 ms (see the upper sequence of Figure 1). In the sequential presentation condition each item was presented alone for 250 ms, with 500ms of only the background onscreen between the presentations of items 1 and 2, and items 2 and 3 (bottom sequence of Figure 1). In the simultaneous condition, items were presented in the same three locations on every trial. These locations were near the center of the screen with one item above and to the left of fixation, one above and to the right, and one directly below fixation. In the sequential condition, the presentation of items was always in the center of the screen, at the location of the fixation cross.

After item presentation there was 250 ms of only background screen presentation, followed by a post-perceptual mask which was presented for 100 ms. The post-perceptual mask consisted of the two symbols “<“ and “>“ superimposed on top of one another with line thickness approximately equal to the memory stimuli (see Figure 1 for a graphical example). After mask offset the retention interval began. This interval was 1, 6, or 12s in length. At the end of the retention interval a single item memory probe was presented in the same location as one of the memory items. Participants responded to the probe by pressing the “s” key if they believed that the item was the same as the item shown in that position during memory-item presentation, or by pressing the “d” key if they believed that item was different. On half of the trials the item was the same as the originally presented item. Different probe items were never items presented at the non-probed positions in the memory set, rather they were always new items.

Before the experimental trials of each presentation method participants completed 12 practice trials. The practice trials were the same as the experimental trials in all respects except that there were only 2 items to remember and the retention interval duration was always 1s in length.

In all of the experiments, the presentation times of the stimuli were 250 ms for each of three characters in the sequential condition, and 750 ms for the three characters together in the simultaneous condition, equating presentation time per character across conditions. In this first experiment, to prevent characters in the sequential condition from perceptually interfering with one another, a 500-ms blank screen was placed between each two characters, as noted above. The result was that both the encoding time and the consolidation time per item were shorter in the simultaneous condition than in the sequential condition.

Results

Mean proportion correct is presented for all conditions in Figure 2. Visual inspection of the means shows that performance was better with sequential presentation than with simultaneous presentation. Most time-based forgetting appears between 1s and 6s, with forgetting in the simultaneous condition being greater than in the sequential condition. Forgetting over time appears to occur for both presentations methods, although to a much greater degree with simultaneous presentation of memory items. Mean performance for each serial position under all sequential presentation conditions is given in Table A1 of the appendix.

Figure 2.

Mean proportion correct for all conditions in Experiment 1. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

A 2 (Presentation Method) x 3 (Retention Interval Duration) x 2 (Counter-balance Order) Mixed Factors ANOVA of proportion correct demonstrates several effects. Significant main effects were found for Presentation Method, F(1, 30)=16.84, p<.001, ηp2= 0.36 (means; sequential=.83, simultaneous=.78), and Retention-Interval Duration, F(2,60)=20.57, p<.001, ηp2=0.41 (means; 1s=.85, 6s=.77, 12s=.79), indicating that overall performance was better for sequential than simultaneous presentation and that performance was better with shorter retention intervals. Most importantly, there was also a significant interaction of Presentation Method with Retention-Interval Duration, F(2,60)=4.52, p<.05, ηp2=0.13 (means: sequential 1s=.86, 6s=.82, 12s=.81; simultaneous 1s=.85, 6s=.73, 12s=.76), indicating that the rate of time-based forgetting was different for sequential and simultaneous presentation methods. Inspection of the condition means shows that forgetting time-based forgetting was more severe in the simultaneous condition than in the sequential condition. The main effect of Counter-Balance Order was not significant, and all interactions of Counter-Balance Order with other factors failed to approach significance, all p>.3.

In order to determine whether duration-based forgetting in the sequential condition reached the threshold for significance, a one-factor (Retention-Interval Duration) Repeated Measures ANOVA of accuracy was conducted with the data from the sequential condition only. A significant effect of Retention-Interval Duration was found, F(2,62)=4.11, p<.05, ηp2=0.12 (means: 1s=.86, 6s=.82, 12s=.81). The same analysis was also conducted using only data from the simultaneous condition. This analysis produced a significant result with a much larger effect size, F(2,62)=18.60, p<.001, ηp2=0.37 (means: 1s=.85, 6s=.72, 12s=.76).

We also estimated the amount of forgetting across the retention interval by fitting Cowan’s k for all participants at each retention interval. Cowan’s k is a measure of the number of items maintained in working memory after accounting for guessing (Cowan, 2001). The k-values reported here were estimated following the method described by Morey (2011a), using the WMCapacity package for the R Statistical environment (Morey, 2011b). When the sequential presentation method was used participants forgot, on average, 0.19 items between 1 and 12s (mean number of items remembered: 1s=2.20, 6s=2.00, 12s=2.01). When the simultaneous presentation method was used participants forgot, on average, 0.39 items between 1 and 12s (mean number of items remembered: 1s=2.03, 6s=1.57, 12s=1.64). Although we report non-integer values for the number of items remembered and forgotten, it could be that participants only remember whole items on any given trial and that non- integer values simply represent variation in the number of items remembered from trial to trial.

Discussion

Experiment 1 demonstrated a clear effect of presentation method on performance. Sequential presentation of stimuli resulted in more accurate performance than simultaneous presentation and less forgetting as a function of time. A small amount of forgetting was found with sequential presentation, but roughly double that forgetting rate was found with simultaneous presentation. These results provide clear evidence that, under the present conditions, sequential presentation of memory items led to better performance overall and slower rates of forgetting than simultaneous presentation.

Experiment 2

The conclusion from Experiment 1 is clear: Simultaneous presentation led to greater rates of forgetting than sequential presentation. There is, however, a potential confound which prevents us from identifying the mechanism driving the difference in forgetting rates. In Experiment 1, the total time memory items were onscreen was held constant across presentation methods, but the total time between item offset and mask onset was different (see Figure 1). The type of mask we used, a post-perceptual pattern mask, is used to overwrite retinal afterimages and sensory memory representations of the stimuli, thereby halting further encoding (Massaro, 1970; Saults & Cowan, 2007; Vogel et al., 2006). If longer encoding times lead to a working memory trace that is more robust against time-based forgetting, then this difference in unmasked time should result in lower decay rates with sequential presentation.

In Experiment 2 we tested whether differences in encoding time could account for the greater rate of forgetting with simultaneous presentation. In this experiment, the simultaneous presentation condition remains the same as in Experiment 1, while the sequential condition is changed so as to preserve across conditions the equal presentation times while now also equating the encoding time per character (Figure 3). Recall that in the simultaneous condition, the three-character array is followed by a 250-ms blank screen, and then by a mask. In this experiment, to match this encoding time across conditions, in the sequential condition the blank screen after each character was 83 ms, followed by a mask. Consequently, encoding time per character in both conditions was 250+83 ms (because 250/3 is approximately 83 ms).

Figure 3.

An example of a single simultaneous presentation trial, top, and a single seqential presentation trial, bottom, in Experiment 2.

It should be noted that while this change equates across conditions the total time that could be used for sensory and perceptual encoding, it also introduced more interfering events in the sequential presentation conditions. These additional events may drive down overall accuracy in the sequential presentation conditions of Experiment 2 relative to Experiment 1 (Oberauer & Lewandowsky, 2008).

If equating the total encoding time results in equal rates of forgetting for both sequential and simultaneous presentation methods, then it clearly indicates that increasing the amount of time for sensory and perceptual encoding leads to memory traces which are more resistant to time-based forgetting.

Method

Participants

Thirty-six college students (18 female, 18 male, ages 18–21) enrolled in introductory psychology at the University of Missouri participated in the experiment in exchange for partial course credit. The participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 counterbalancing orders, with an equal number of participants in each group. All participants were screened to ensure that they did not speak or read any of the languages from which the memory stimuli were taken, and had not lived in any of the countries in which they may have regularly been exposed to the figures used in the experiment.

Materials

All materials were the same as in Experiment 1.

Procedure

The procedure was identical to Experiment 1 except for one change. In the sequential condition, the blank period following each item presentation (see Figure 3) was now used differently. After item presentation in the sequential condition there was an 83-ms blank screen, followed by a mask which remained onscreen for 100-ms. There was an additional blank period of 317 ms after the mask following Items 1 and 2, but not following Item 3. This was done in order to maintain the constant 500-ms time period between each memory item offset to onset.

Results

Mean proportion correct is presented for all conditions in Figure 4. Visual inspection of the means shows that performance tended to be better in the sequential condition than the simultaneous condition. This difference was smaller than in Experiment 1, likely because accuracy was shifted down in the sequential presentation condition of Experiment 2 due to the introduction of multiple interfering masking events and reduced encoding time. Just as in Experiment 1, forgetting over time appears to occur for both presentations methods, and once again it is to a much greater degree with simultaneous presentation of memory items. Mean performance for each serial position under all sequential presentation conditions is given in Table A2 of the appendix.

Figure 4.

Mean proportion correct for all conditions in Experiment 2. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

A 2 (Presentation Method) x 3 (Retention Interval Duration) x 2 (Counter-balance Order) Mixed Factors ANOVA of proportion correct demonstrates several effects. A significant main effect was found for Retention-Interval Duration, F(2,68)=27.28, p<.001, ηp2=0.45 (means; 1s=.80, 6s=.72, 12s=.71), indicating that performance was better with shorter retention intervals. The main effect of Presentation Method was marginal F(1,34)=3.96, p=.055, ηp2=.10. Most importantly, there was also a significant interaction of Presentation Method with Retention-Interval Duration, F(2,68)=7.11, p<.005, ηp2=0.17 (means: sequential 1s=.79, 6s=.74, 12s=.74; simultaneous 1s=.81, 6s=.71, 12s=.68), indicating that the rate of time-based forgetting was different for sequential and simultaneous presentation methods. Inspection of the condition means shows that duration-based forgetting was again greater in the simultaneous condition than in the sequential condition. The main effect of Counter-Balance Order was not significant, and all interactions of Counter-Balance Order with other factors failed to approach significance, all p>.3.

A 2 (Presentation Method) x 3 (Retention Interval Duration) x 2 (Experiment) Mixed Factors ANOVA of proportion correct was conducted in order to confirm that the rates of forgetting were equivalent across Experiments 1 and 2. A change in the overall rate of forgetting would emerge as a significant interaction between Duration and Experiment, while a change in the forgetting rate difference across presentation methods would emerge as a significant three-way interaction between Presentation Method, Duration, and Experiment. While there was a main effect of Experiment, F(1,66)=8.75, p<.005, ηp2=.12, and a marginal interaction of Experiment with Presentation Method, F(1,66)=3.61, p=.062, ηp2=.05, the key interactions that included Experiment as a factor were not significant. Duration x Experiment, F(2,132)=1.05, p>.3, ηp2=.02, Presentation Method x Duration x Experiment, F(2,132)=2.34, p>.1, ηp2=.03.

We also estimated the amount of forgetting across the retention interval by fitting Cowan’s k (Cowan, 2001) for all participants at each retention interval following the method detailed by Morey (2011a). When the sequential presentation method was used participants forgot, on average, 0.22 items between 1 and 12s (mean number of items remembered: 1s=1.76, 6s=1.52, 12s=1.55). When the simultaneous presentation method was used participants forgot, on average, 0.67 items between 1 and 12s (mean number of items remembered: 1s=1.87, 6s=1.36, 12s=1.20).

Discussion

In Experiment 2 the amount of time that could be used for encoding while the memory items were not onscreen was equated across presentation methods. This was implemented through the presentation of a mask 83 ms after the offset of each memory item in the sequential presentation condition. The addition of this mask did not change the rate of forgetting in the sequential condition from that observed in Experiment 1. We again observed a significant interaction between Presentation Method and Retention-Interval Duration due to a larger rate of loss in the simultaneous presentation condition than in the sequential presentation condition (see Figure 4). This result indicates that the difference in time-based forgetting does not arise from differences in encoding time, but rather from differences in forgetting processes, maintenance, or some other cognitive process that comes into play after basic encoding processes.

Although the critical comparisons of interest were obtained within Experiment 1 and were replicated within Experiment 2, is worthwhile to compare performance levels across experiments. The simultaneous conditions of Experiments 1 and 2 used identical procedures, and produced mean proportions correct that were similar, perhaps differing only because of sampling differences (Experiment 1,.78; Experiment 2,.74). In contrast, the procedures of the sequential conditions of these experiments differed by the introduction of a mask in Experiment 2, which resulted in a larger decrease in performance level compared to the first experiment (Experiment 1, .83; Experiment 2, .75). Thus, even though limiting encoding time in the sequential condition did not eliminate the time-based loss, it did lower overall performance.

Experiment 3

Jolicouer and Dell’acqua, (1998) differentiate between the processes of encoding, basic sensory and perceptual processing that allow one to recognize and attend to a stimuli, and consolidation of a working memory trace, processes that lead to remembering an item over the short-term. The masking of memory stimuli using pattern masks such as those used in our experiments is thought to overwrite the perceptual afterimage and sensory memory traces of the stimuli which they follow (Massaro, 1970; Saults & Cowan, 2007; Vogel et al., 2006), thereby ending the encoding of these stimuli, but not necessarily ending the consolidation of already encoded traces. If consolidation into working memory relies on central resources and the existence of an encoded memory trace, as suggested by Jolicouer & Dell’acqua, (1998), presentation of a mask should not halt it.

In the sequential conditions of Experiments 1 and 2, there was extra free time after each mask that could be used by the consolidation process, if it exists. If working memory consolidation exists and serves to protect memory traces against forgetting, then the decreased rate of forgetting we observed with sequential presentation should be expected. In Experiment 3 we test this consolidation hypothesis by removing the free periods of time between the presentations of memory items in the sequential condition (Figure 5). In this way item presentation time, total encoding time, and total working memory consolidation time are all held constant across both sequential and simultaneous presentations. In both conditions, there was 250 ms per character available for encoding, followed by a 250-ms blank period, and then a mask. This differs from Experiment 2 in that the previous experiment equated only presentation and encoding time, but not the time available for any consolidation of working memory that continues after masking.

Figure 5.

An example of a single simultaneous presentation trial, top, and a single seqential presentation trial, bottom, in Experiment 3.

Method

Participants

Thirty college students (18 female, 12 male, ages 18–22) enrolled in introductory psychology at the University of Missouri participated in the experiment in exchange for partial course credit. The participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 counterbalancing orders, with an equal number of participants in each group. All participants were screened to ensure that they did not speak or read any of the languages from which the memory stimuli were taken, and had not lived in any of the countries in which they may have regularly been exposed to the figures used in the experiment.

Materials

All materials were the same as in Experiments 1 and 2.

Procedure

The procedure was identical to Experiment 1 except for one change. In the sequential condition, the blank periods following the presentations of items 1 and 2 were removed (see Figure 5).

Results

Mean proportion correct is presented for all conditions in Figure 6. Visual inspection of the means shows that performance tended to be better with simultaneous presentation than with sequential presentation. Time-based forgetting is clearly present for both presentation methods and clearly occurs at a comparable rate. Mean performance for each serial position under all sequential presentation conditions is given in Table A3 of the appendix.

Figure 6.

Mean proportion correct for all conditions in Experiment 3. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

A 2 (Presentation Method) x 3 (Retention Interval Duration) x 2 (Counter-balance Order) Mixed Factors ANOVA of proportion correct demonstrates two significant effects. Significant main effects were found for Presentation Method, F(1,28)= 10.44, p<.01, ηp2= 0.27 (means; sequential=.69, simultaneous=.73), and Retention-Interval Duration, F(2,56)= 32.07, p<.001, ηp2= 0.53 (means; 1s=.77, 6s=.69, 12s=.67), indicating that performance was better with simultaneous presentation and shorter retention intervals. Most importantly, unlike Experiments 1 and 2, in this experiment there was no interaction of Presentation Method with Retention-Interval Duration, F(2,56)= 1.11, p=.34, indicating that the rate of time-based forgetting was similar for sequential and simultaneous presentation methods. The main effect of CounterBalance Order was not significant, nor were any interactions of Counter-Balance Order with other factor, all p>.3.

We also estimated the amount of forgetting across the retention interval by fitting Cowan’s k (Cowan, 2001) for all participants at each retention interval following the method detailed by Morey (2011a). When the sequential presentation method was used participants forgot, on average, 0.41 items between 1 and 12s (mean number of items remembered: 1s=1.44, 6s=1.08, 12s=1.03). When the simultaneous presentation method was used participants quite similarly forgot, on average, 0.45 items between 1 and 12s (mean number of items remembered: 1s=1.69, 6s=1.39, 12s=1.24).

Discussion

The results of Experiment 3 are in clear contrast to Experiments 1 and 2. In Experiment 3 sequential and simultaneous presentation methods resulted in equal rates of forgetting. The key difference between this experiment and the previous two experiments is that the total time from the start of item presentation to the onset of the final mask was held constant across conditions in this experiment. Experiment 1 only held constant the amount time items were shown onscreen and Experiment 2 held constant the amount of time items were shown onscreen and the amount of time from stimulus offset to mask. Neither of these equalities resulted in equal rates of forgetting. Instead it seems that the total amount of time available to consolidate the stimuli into working memory is what is important. (Note, though, that this finding was obtained always with fairly substantial encoding times of at least 250 ms per item.) Critically, this consolidation period is not stopped by overwriting sensory and perceptual information.

Although the rates of forgetting in Experiment 3 were comparable across conditions, the levels of performance were different. The sequential condition now produced poorer performance than the simultaneous condition. This could be explained on the grounds that the sequential condition did not provide the spatial cues available in the simultaneous condition, and did not allow as much flexibility in when attention is allocated to each item. This lower level of performance was presumably not seen in Experiments 1 and 2 because performance did not fall off much across delays in the sequential condition, given the more ample consolidation time available for that condition in those experiments. In Experiment 4, we control consolidation across conditions in a different way, and in doing so we manage to reduce greatly the main effect of condition as well as the interaction between condition and delay.

Experiment 4

The results of Experiment 3 indicate that the amount of time available for consolidation of working memory is the key factor in determining the magnitude of time-based forgetting. If this is true, then lengthening the time available for consolidation in the simultaneous presentation condition should decrease the associated rate of forgetting. In Experiment 4 we replicate Experiment 1, but change the simultaneous presentation condition so that its presentation method matches the timing of the sequential condition. Specifically, in the simultaneous presentation condition the full array is presented 3 times for 250ms each time. These presentations are separated by 500ms of free time without a mask, just as in the sequential presentation condition of both this experiment and Experiment 1 (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

An example of a single simultaneous presentation trial, top, and a single seqential presentation trial, bottom, in Experiment 4.

If our hypothesis is correct and consolidation time is what creates a difference between sequential and simultaneous presentation methods, then we should again observe no differences in the rate of forgetting across presentation conditions in this experiment. We might also observe a lower rate of forgetting than in Experiment 3 due to the increased amount of time for consolidation.

Method

Participants

Thirty college students (19 female, 11 male, ages 18–23) enrolled in introductory psychology at the University of Missouri participated in the experiment in exchange for partial course credit. The participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 counterbalancing orders, with an equal number of participants in each group. All participants were screened to ensure that they did not speak or read any of the languages from which the memory stimuli were taken, and had not lived in any of the countries in which they may have regularly been exposed to the figures used in the experiment.

Materials

All materials were the same as in Experiments 1, 2, and 3.

Procedure

The procedure was identical to Experiment 1 except for one change. In Experiment 4, item presentation proceeded in the same manner for simultaneous presentation as in the sequential presentation condition, except that the full array was presented during the period that each of the individual items would have been presented in the sequential condition (see Figure 7). Thus, in the present condition called simultaneous, the full array was presented for 250ms, followed by a 500ms blank period, then the full array was presented again for 250ms, followed by a 500ms blank period, and then the full array was presented for a final 250 ms.

Results

Mean proportion correct is presented for all conditions in Figure 8. Visual inspection of the means shows that performance tended to be very similar for both presentation methods. Time-based forgetting is clearly present and occurs at a very comparable rate across conditions. It is noteworthy that the rate of forgetting here appears to be roughly half the rate of forgetting as in Experiment 3. Mean performance for each serial position under all sequential presentation conditions is given in Table A4 of the appendix.

Figure 8.

Mean proportion correct for all conditions in Experiment 4. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

A 2 (Presentation Method) x 3 (Retention Interval Duration) x 2 (Counter-balance Order) Mixed Factors ANOVA of proportion correct demonstrates only one significant effect. This was the main effect of Retention-Interval Duration, F(2,56)=8.81, p<.001, ηp2=0.24 (means; 1s=.84, 6s=.81, 12s=.78), indicating that performance was better with shorter retention intervals. All other effects main effects and interactions failed to approach significance, all p>.1.

We also estimated the amount of forgetting across the retention interval by fitting Cowan’s k (Cowan, 2001) for all participants at each retention interval following the method detailed by Morey (2011a). When the sequential presentation method was used participants forgot, on average, 0.22 items between 1 and 12s (mean number of items remembered: 1s=2.04, 6s=1.86, 12s=1.82). When the simultaneous presentation method was used participants forgot, on average, 0.31 items between 1 and 12s (mean number of items remembered: 1s=2.17, 6s=1.99, 12s=1.86).

Discussion

The results of Experiment 4 are clear and replicate the findings of Experiment 3. When total consolidation time is equated, forgetting rates are equivalent for sequential and simultaneous presentation. Forgetting in Experiment 4 was much less than in Experiment 3, likely due to the increased amount of free time for working memory consolidation.

General Discussion

There has been debate in recent years over whether time-based forgetting exists. We, and others, have argued that time-based forgetting occurs as a function of the length of the retention interval (Cowan & Aubuchon, 2008; McKeown & Mercer, 2012; Ricker & Cowan, 2010). Our experiments here corroborate these accounts. Significant forgetting was always observed as a function of the retention-interval duration, regardless of presentation method. This time-based forgetting cannot be explained by existent retro-active interference accounts because there are no interfering events introduced between memory item presentation and memory test that would lead to the disruption of memory traces. Here we find, however, that the amount of consolidation, i.e., processing time with or without a mask, is a key determinant of the amount of loss.

Consolidation and Forgetting: Reconciliation of the Literature

Those researchers who generally use serial recall of letters to investigate forgetting in working memory have argued very persuasively that there is little or no time-based forgetting which occurs based on the length of memory retention (Barrouillet et al. 2004; Gavens & Barrouillet, 2004; Lewandowsky et al., 2004; Oberauer & Lewandowsky, 2008). These findings must be reconciled with the present results, and those of Ricker and Cowan (2010), using arrays of unfamiliar characters that do show loss over time, and those of McKeown & Mercer (2012) using complex tones. We suggest that the difference is in the strength of information consolidated into working memory. We found that greater amounts of time for working memory consolidation lead to slower rates of forgetting. Studies using sequential presentation generally use presentation rates around 1 item per second, with a variable amount of time for further working memory consolidation after each item presentation. This is much longer per item than even the sequential presentation times used here and in other visual array memory studies (i.e., presentation of all memory items concurrently for less than 1 s).

The rate of time-based forgetting we observed across experiments was variable in precise value when similar consolidation times were used but consistent in the general pattern. Long consolidation times always led to much slower rates of time-based forgetting (mean items forgotten between 1 and 12s; Expt. 1 sequential =.19, Expt. 2 sequential =.22, Expt. 4 sequential=.22, simultaneous=.31) than did short consolidation times (mean items forgotten; Expt. 1 simultaneous =.39, Expt. 2 simultaneous =.67, Expt. 3 sequential=.41, simultaneous=.45). Although there may be individual differences in the rate of item consolidation, item decay, or both, the pattern related to consolidation is clear.

Past conclusions from studies using both item presentation methodologies appear to be on target, but bound by method-specific idiosyncrasies. Duration-based forgetting does occur, but can be reduced and possibly alleviated by increasing the amount of time available for working memory consolidation. Even if a small amount of time-based forgetting always remains, detecting the slow rate of forgetting would be very difficult with the sequential presentation methods used by many researchers. Indeed, close inspection of the results of some studies which have been used to argue for no effect of retention-interval duration on accuracy appear to show a small yet consistent duration-based effect (i.e., Altmann & Schunn, 2012; Gavens & Barrouillet, 2004; Lewandowsky et al., 2004) which often fails to reach the threshold for significance.

A study which at first may seem in conflict with our findings is that of Berman et al. (2009). These researchers used simultaneous presentation of memory items and showed results which they argue offer little to no evidence for an effect of time-based forgetting. In this study, four short highly-familiar words were presented for 2s, a period much longer than is generally used with simultaneous presentation. As such, we would expect a relatively long working memory consolidation period and little time-based forgetting with this procedure. While this study did show interference effects despite the long consolidation period and the lack of time-based forgetting, we make no claim that working memory consolidation must abolish both time-based forgetting and interference-based forgetting equally or completely in all circumstances. We did not manipulate the presence or intensity of interference in our study so we can only speculate as to how working memory consolidation would affect interference-based forgetting. That said, it is possible that if Berman et al. had used a shorter consolidation time they would have observed even larger interference effects. Indeed, when Campoy (2012) used a similar approach to Berman et al. (2009) but made very significant changes to the methodology they did find time-based forgetting, although only over a very brief time period (under 3 s). The differences between our own study, Berman et al. (2009), and Campoy (2012), demonstrate the strength of the current work in that here we begin to disentangle the basic reasons behind these differences.

Basis of Consolidation

One explanation of the working memory consolidation process has to do with the relation between memory representations and mnemonic processes that operate on them. Longer periods of free time during item presentation could limit forgetting because they allow executive processes to organize and execute more efficient maintenance strategies which counteract time-based forgetting. Specific examples of this process could be the internal identification of targets for Cowan (1988; 1995)’s focus of attention or Oberauer (2002)’s region of direct access, or time for refreshing the traces according to Barrouillet et al. (2004)’s attentional refreshing cycle. Future research will be necessary to differentiate consolidation based on a strengthening trace versus improvement in maintenance mechanisms.

Another interesting candidate for the consolidation process has to do with desyncronization of the firing of neurons which make up the trace. According to some prominent neural theories, (for example, see Lisman & Jensen, 2013), a short-term trace consists of synchronized firing of neurons representing different features of an object, with different working memory objects firing in sequence. Forgetting then could result from desynchronization. This is compatible with our own embedded-process modeling framework (Cowan, 1988, 1995) of memory. Consolidation could be a gradual strengthening of the short-term firing relationship between the neurons that make-up the memory trace. This would occur only when attention is focused upon the trace during the initial life of the memory. Strengthening the firing relationship of neurons within the trace would result in slower desynchronization and forgetting.

A more functional instantiation of the consolidation process could be the identification of known patterns within the memory representation. For example, when unfamiliar visual items are used, as in our own study, consolidation could consist of identifying known patterns within the stimuli which would make them easier to remember by simplifying the memory items. This would increase the functional capacity as more simple items can be maintained than complex items (Awh, Barton, & Vogel, 2007). This process would also include the identification of chunks. For example, a set of oriented line stimuli could be chunked into a single larger shape through the application of attention while the memory representation is still fresh. There is evidence that items that reside in the focus of attention at once can become associated, leading to multi-item chunks (Cowan, Donnell, & Saults, 2013).

An alternative explanation of our results is that verbal rehearsal is responsible for the consolidation effect we observed. This idea seems plausible at first glance, but cannot account for our results given previous research. The argument for a verbal rehearsal explanation would be the following. On each trial verbal labels are given to the symbols and a verbal rehearsal loop is then initiated. This processing would initially require central resources (Naveh-Benjamin & Jonides, 1984) and the longer periods of free time during sequential presentation may have facilitated it. Fortunately, Ricker et al. (2010) showed that articulatory suppression, a manipulation that prevents verbal rehearsal, did not impair memory performance for arrays of unfamiliar characters any more than did finger tapping, an activity that should have no effect on verbal rehearsal, but is otherwise similar to articulatory suppression. If the ability to use verbal rehearsal does not improve memory for arrays of unfamiliar characters it is difficult to imagine how it could change the rate of forgetting.

Impact of Consolidation and Forgetting on Working Memory Research

Those who use methods with longer consolidation periods often compound the difficulty of finding time-based loss by using verbal memory stimuli. Familiar verbal materials have shown a slower rate of forgetting than non-verbal materials (Ricker & Cowan, 2010; Ricker Spiegel, & Cowan, under review). We believe this is due to two factors. First, in some studies participants are free to rehearse verbal materials at their leisure. This likely counteracts decay of at least some items, leading to no forgetting across the retention interval for the rehearsed items. However, verbal rehearsal is not possible in all studies.

A second, complementary, explanation of why verbal materials lead to slower rates of forgetting is that familiar verbal items may have a faster rate of consolidation than unfamiliar visual items. Jolicouer and Dell’acqua (1998) provide some evidence which supports this claim, showing that symbols are consolidated into working memory more slowly than letters. These authors investigated working memory consolidation by asking participants to remember masked letters or symbols and to perform a tone identification task shortly after post-perceptual mask presentation. When presenting the tone identification task at longer stimulus onset asynchronies from the mask stimuli participants responded faster, indicating less disruption from working memory consolidation. Using symbols instead of letters resulted in longer consolidation periods and slower overall tone task performance. This finding implies that disruption of consolidation should occur less often for letters than for symbols in most experimental paradigms. Our conclusions from the experiments presented in the present work in combination with the findings of Jolicoeur and Dell’acqua (1998) would lead one to predict a lower rate of forgetting for familiar verbal letters than for less familiar characters and symbols.

It is clear from our results that working memory consolidation processes determine the robustness of the trace against time-based forgetting. It will be interesting to test in future research whether the same consolidation processes determine both the vulnerability to time-based and interference-based forgetting. Although questions of how the passage of time leads to forgetting from working memory remain, the present research brings light to an ongoing debate and removes a significant hurdle to further understanding of the nature of forgetting from moment to moment. Whether or not time-based forgetting will be observed in a working memory task is largely determined by the amount of time allowed for consolidation of working memory.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Jeff Rouder and Karen Hebert for helpful comments. Funding for this project was provided by NIMH Grant #1F31MH094050 to Ricker and NICHD Grant #2R01HD021338 to Cowan.

Appendix

Tables of Mean Accuracy and SEM in Response to Probes Matching Each Presentation Serial Position in the Sequential Condition of Each Experiment.

Table A1.

Mean Accuracy for all Sequential Presentation Conditions by Serial Position in Experiment 1

| Retention-Interval Duration | Serial Position

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 1s | 0.87 (0.02) | 0.84 (0.03) | 0.86 (0.03) |

| 6s | 0.82 (0.02) | 0.80 (0.02) | 0.83 (0.02) |

| 12s | 0.83 (0.02) | 0.79 (0.02) | 0.82 (0.03) |

Note. Standard Errors of the Mean are in parentheses.

Table A2.

Mean Accuracy for all Sequential Presentation Conditions by Serial Position in Experiment 2

| Retention-Interval Duration | Serial Position

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 1s | 0.81 (0.02) | 0.72 (0.04) | 0.86 (0.02) |

| 6s | 0.72 (0.03) | 0.72 (0.03) | 0.76 (0.04) |

| 12s | 0.69 (0.03) | 0.74 (0.03) | 0.77 (0.03) |

Note. Standard Errors of the Mean are in parentheses.

Table A3.

Mean Accuracy for all Sequential Presentation Conditions by Serial Position in Experiment 3

| Retention-Interval Duration | Serial Position

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 1s | 0.75 (0.02) | 0.69 (0.03) | 0.81 (0.02) |

| 6s | 0.59 (0.03) | 0.62 (0.02) | 0.77 (0.03) |

| 12s | 0.64 (0.02) | 0.61 (0.03) | 0.69 (0.03) |

Note. Standard Errors of the Mean are in parentheses.

Table A4.

Mean Accuracy for all Sequential Presentation Conditions by Serial Position in Experiment 4

| Retention-Interval Duration | Serial Position

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 1s | 0.83 (0.02) | 0.85 (0.02) | 0.82 (0.03) |

| 6s | 0.80 (0.02) | 0.78 (0.02) | 0.81 (0.02) |

| 12s | 0.80 (0.03) | 0.78 (0.03) | 0.76 (0.03) |

Note. Standard Errors of the Mean are in parentheses.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Awh E, Barton B, Vogel EK. Visual working memory represents a fixed number of items regardless of complexity. Psychological Science. 2007;18:622–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmann EM, Schunn CD. Decay versus interference: A new look at an old interaction. Psychological Science. 2012;23:1435–1437. doi: 10.1177/0956797612446027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrouillet P, Bernardin S, Camos V. Time constraints and resource sharing in adults’ working memory spans. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2004;133:83–100. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.133.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrouillet P, De Paepe A, Langerock N. Time causes forgetting from working memory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2012;19:87–92. doi: 10.3758/s13423-011-0192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrouillet P, Portrat S, Camos V. On the law relating processing to storage in working memory. Psychological Review. 2011;118:175–192. doi: 10.1037/a0022324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman MG, Jonides J, Lewis RL. In search of decay in verbal short-term memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2009;35:317–333. doi: 10.1037/a0014873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campoy G. Evidence for decay in verbal short-term memory: A commentary on Berman, Jonides, and Lewis (2009) Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2012;38:1129–1136. doi: 10.1037/a0026934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan N. Evolving conceptions of memory storage, selective attention, and their mutual constraints within the human information processing system. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;104:163–191. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.104.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan N. Attention and memory: An integrated framework. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan N. The magic number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2001;24:87–114. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X01003922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan N, AuBuchon AM. Short-term memory loss over time without retroactive stimulus interference. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2008;15:230–235. doi: 10.3758/PBR.15.1.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan N, Donnell K, Saults JS. A list-length constraint on incidental item-to-item associations. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2013 doi: 10.3758/s13423-013-0447-7. Published on-line ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell S. Temporal clustering and sequencing in short-term memory and episodic memory. Psychological Review. 2012;119:223–271. doi: 10.1037/a0027371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavens N, Barrouillet P. Delays of retention, processing efficiency, and attentional resources in working memory span development. Journal of Memory and Language. 2004;51:644–657. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2004.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jolicoeur P, Dell’Acqua R. The demonstration of short-term consolidation. Cognitive Psychology. 1998;36:138–202. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1998.0684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowsky S, Duncan M, Brown GDA. Time does not cause forgetting in short term serial recall. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2004;11:771–790. doi: 10.3758/BF03196705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowsky S, Oberauer K, Brown GDA. No temporal decay in verbal short term memory. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2009;13:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE, Jensen O. The theta-gamma neural code. Neuron. 2013;77(6):1002–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massaro DW. Perceptual processes and forgetting in memory tasks. Psychological Review. 1970;77:557–567. [Google Scholar]

- Massaro DW. Experimental psychology and information processing. Chicago: Rand McNally; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- McKeown D, Mercer T. Short-term forgetting without interference. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0027749. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey CC, Bieler M. Visual short-term memory always requires general attention. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2012 doi: 10.3758/s13423-012-0312-z. Advanced online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey RD. A hierarchical Bayesian model for the measurement of working memory capacity. Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 2011a;55:8–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jmp.2010.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morey RD. WMCapacity: GUI implementing Bayesian working memory models. R package version 0.9.6.6. 2011b http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=WMCapacity.

- Naveh-Benjamin M, Jonides J. Maintenance rehearsal: A two component analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1984;10:369–385. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.10.3.369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oberauer K. Access to information in working memory: Exploring the focus of attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology-Learning Memory and Cognition. 2002;28:411–421. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.28.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberauer K, Kliegl R. A formal model of capacity limits in working memory. Journal of Memory and Language. 2006;55:601–626. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2006.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oberauer K, Lewandowsky S. Forgetting in immediate serial recall: Decay, temporal distinctiveness, or interference? Psychological Review. 2008;115:544–576. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.3.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricker TJ, Cowan N. Loss of visual working memory within seconds: The combined use of refreshable and non-refreshable features. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2010;36:1355–1368. doi: 10.1037/a0020356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricker TJ, Cowan N, Morey CC. Visual working memory is disrupted by covert verbal retrieval. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2010;17:516–521. doi: 10.3758/PBR.17.4.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricker TJ, Spiegel LR, Cowan N. Time-based loss in short-term visual memory is not from temporal distinctiveness. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saults JS, Cowan N. A central capacity limit to the simultaneous storage of visual and auditory arrays in working memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2007;136:663–684. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.136.4.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turvey MT. On peripheral and central processes in vision: inferences from an information processing analysis of masking with patterned stimuli. Psychological Review. 1973;80:1–52. doi: 10.1037/h0033872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergauwe E, Dewaele N, Langerock N, Barrouillet P. Evidence for a central pool of general resources in working memory. Journal of Cognitive Psychology. 2012;24:359–366. doi: 10.1080/20445911.2011.640625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vergauwe E, Barrouillet P, Camos V. Visual and spatial working memory are not that dissociated after all: A time-based resource-sharing account. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2009;35:1012–1028. doi: 10.1037/a0015859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergauwe E, Barrouillet P, Camos V. Do mental processes share a domain-general resource? Psychological Science. 2010;21:384–390. doi: 10.1177/0956797610361340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel EK, Woodman GF, Luck SJ. The time course of consolidation in visual working memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2006;32:1436–1451. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.32.6.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman GF, Vogel EK, Luck SJ. Flexibility in visual working memory: Accurate change detection in the face of irrelevant variations in position. Visual Cognition. 2012;20:1–28. doi: 10.1080/13506285.2011.630694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White KG. Dissociation of short-term forgetting from the passage of time. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 2012. 2012;38:255–259. doi: 10.1037/a0025197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Luck SJ. Sudden death and gradual decay in visual working memory. Psychological Science. 2009;20:423–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]