Abstract

Engineered nanomaterials (ENMs) continue to attract significant attentions because they have novel physicochemical properties that can improve the functions of products that will benefit human lives. However, the physicochemical properties that make ENMs attractive could interact with biological systems and induce cascades of events that cause toxicological effects. Recently, there are more studies suggesting inflammasome activation may play an important role in ENMs-induced biological responses. Inflammasomes are a family of multi-protein complexes and are increasingly recognized as major mediators of host immune system. Among these, NLRP3 inflammasome is the most studied one that could directly interact with ENMs to generate inflammatory responses. In this review, we aim to link the ENM physicochemical properties to NLRP3 inflammasome activation. The understanding of the mechanisms of ENMs-NLRP3 inflammasome interaction will provide us strategies for safer nanomaterial design and therapy.

Keywords: Engineered Nanomaterials (ENMs), Inflammasome, Inflammation, Nanotoxicology, NLRP3, Oxidative Stress

1. Introduction

Nanotechnology offers the prospect of utilizing nano-sized materials with novel physicochemical properties to improve the functions of commercial products, which could significantly improve the quality of life. In fact, engineered nanomaterials (ENMs) with various physicochemical properties have been used in many applications including cosmetics, electronic devices, drug delivery systems, and other personal health care products.[1-3] With the rapid commercialization and widespread use of ENMs, there is an increase in the opportunity of ENM exposure to human beings and environment, which has generated substantial concern that the ENMs could induce adverse health effects.[4-6] Increased studies have demonstrated that some of the ENMs are not inherently benign,[1] and the physicochemical characteristics of nanoparticles are critical in determining their in vivo biocompatibility.[7] For example, studies in the University of California Center for Environmental Implications of Nanotechnology (UC CEIN) have demonstrated that dissolution, ROS generation, aspect ratio, material bandgap, surface chemistry and surface charge play important roles in ENMs induced toxicity (Please see accompanying article in this issue).[8] And Nanotechnology Characterization Laboratory (NCL) at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) evaluated more than 200 different types of nanoparticles for diagnostics and therapeutics, and identified that the hydrophobicity, size and surface charge could be the main parameters affecting the biocompatibility of nanoparticles.[9] In spite of these progresses, the toxicological mechanisms by which ENMs could generate biological injury at the nano-bio interface are still not fully understood. Recently, more studies show that ENM properties could influence immune system and cause undesirable side-effects.[10] Immune cells could recognize and then internalize ENMs. And these processes could initiate inflammatory responses. Among the proposed mechanisms of inflammation, inflammasomes are drawing significant attention since they respond to a wide range of stimuli including ENMs;[11, 12] and it has been demonstrated that inflammasome activation is associated with various inflammatory diseases.[13] The core components of inflammasomes belong to two families, the Nod-like receptor (NLR) family including NLRP1, NLRP3, and IPAF, as well as PYHIN (pyrin and HIN200 (haematopoietic interferon-inducible nuclear antigens with 200 amino-acid repeats) domain-containing protein) family including AIM2.[13] They are intracellular multi-protein complexes assembled upon various stimuli, which control the activation of caspase-1 and modulate the secretion of cytokines including interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-18 (IL-18) in innate immune system.[14, 15] Furthermore, the production of cytokines induces activation of the adaptive immunity to regulate host defenses.[16] Among these inflammasomes, NLRP3 inflammasome is the most studied one and its activation has been linked to various stimuli including ENMs with different physicochemical properties. In this review, we aim to bridge ENM physicochemical properties to NLRP3 inflammasome activation. The understanding of activation mechanisms will provide knowledge to design safer nanomaterials as well as to prevent or treat potential ENMs-induced adverse health effects.

2. Inflammasome Family and Their Roles in Inflammatory Diseases

Inflammasomes comprise a group of intracellular multi-protein complexes that can respond to exogenous stimuli.[15, 17] There are mainly four types of inflammasomes that include NLRP1, NLRP3, IPAF and AIM2 inflammasomes[15] (Figure 1). Inflammasomes are mainly expressed in immune cells including dendritic cells,[18-21] macrophages,[22-25] mast cells,[26] microglial cells,[27] and primary monocytes.[28-30] However, inflammasomes are also found in cell types beyond the immune system, including astrocytes,[31] epithelial cells,[32] fibroblasts,[33] keratinocytes,[34-36] and neurons,[31] which suggests inflammasomes could play a bigger role in response to stimuli and induction of inflammatory response/disease outcomes in biological system (Table 1). Each type of inflammasome contains distinctive domains and is responsive to specific stimuli (Table 2). NLRP1 is the first identified among NLR families. It contains a pyrin domain (PYD), a nucleotide-binding domain (NBD), a carboxy-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain, a caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD) and a domain with unknown function (FIIND) (Figure 1). It responds to anthrax lethal toxin[22, 37] and muramyl dipeptide (MDP),[38] a peptidoglycan component of both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. The second one is IPAF inflammasome, which is also known as NLRC4 inflammasome. IPAF contains an N-terminal CARD, a central NBD, and a C-terminal LRR domain. It is stimulated by gram-negative bacteria.[39, 40] The third one is AIM2 inflammasome, which belongs to PYHIN family. It contains PYD and HIN domains, and is specifically activated by dsDNA.[24] The last one is NLRP3 (also known as NALP3) inflammasome, which currently is the most studied NLR family member. It contains a PYD, a central NBD and a LRR domain. NLRP3 inflammasome is activated through a wide range of stimuli including pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as viral RNA;[41] damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), such as ATP;[42] fibers/particles including asbestos,[12] quartz,[43] and alum;[44] metabolic products, such as monosodium urate (MSU) crystals;[45] and environmental hazards, such as UV radiation.[34] Recent studies show that NLRP3 inflammasome also responds to ENMs including long aspect ratio materials such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs),[46] titanium oxide nanobelts[47] and cerium oxide nanowires,[48] as well as nanoparticles with cationic charge or certain surface functionalization[49] (Figure 2). Upon activation, NLRP3 recruits the adaptor protein ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein) via PYD-PYD interaction. Further, the ASC binds to the pro-caspase-1 and produces active caspase-1,[50, 51] which processes pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 to the bioactive IL-1β and IL-18. IL-1β is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that is responsible for a diverse array of injuries and infections, and it has been recognized as one of the primary causes of inflammation.[52] IL-18, which shares similar structure and functions with IL-1β, is also recognized as an important regulator of innate and acquired immune responses.[53] IL-1β can cause fever, increase level of circulating nitrogen oxide (NO), recruit neutrophils, and costimulate T cell activation,[54] which is necessary for the clearance of bacterial infection or foreign substances. IL-1β itself also has been shown to exhibit the adjuvant capacity to enhance humoral immunity,[55] and is involved in Th17 cell differentiation from naive T cells.[56] There is a study showing that reduced IL-1β production in NLRP3-/- mice was found to be more susceptible to experimental colitis.[57] However, excessive IL-1β production promotes the production of profibrogenic cytokines and growth factors in the epithelial mesenchymal trophic unit (EMTU) that may lead to lung fibrosis.[46] The activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and subsequent secretion of IL-1β in in vivo models have been associated with several types of diseases including asbestosis (induced by asbestos fibers),[58] silicosis (induced by quartz),[58] gout (induced by long aspect ratio MSU crystals),[45] Alzheimer's disease (induced by fibrillar amyloid-β),[27] and type II diabetes (induced by oligomers of islet amyloid polypeptide)[59] (Figure 2). Also, the NLRP3 gene mutation-induced over-production of IL-1β have been associated with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS)[60]; and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the NLRP3 gene has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn's disease)[61] (Figure 2). Recent studies showed that ENMs with various physicochemical properties could activate NLRP3 inflammasome,[46, 48, 62, 63] suggesting the important role of NLRP3 inflammasome in mediating host defense system against ENM exposures. In the following sections, we'll review the major mechanisms of ENMs-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation. The elucidation of mechanisms of ENMs-NLRP3 inflammasome interaction will help us to link physicochemical properties of ENMs to NLRP3 inflammasome activation, which will provide strategies to minimize potential toxic effects induced by nanomaterials.

Figure 1. Inflammasomes and inflammasome activation.

Four inflammasomes including NLRP1, NLRP3, IPAF and AIM2 inflammasomes have been identified. Each type of inflammasome contains distinctive domains. NLRP1 contains a pyrin domain (PYD), a nucleotide-binding domain (NBD), a carboxy-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain, a caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD) and a domain with unknown function (FIIND). NLRP3 contains a PYD, a central NBD and a LRR domain. IPAF contains an N-terminal CARD, a central NBD, and a C-terminal LRR domain. AIM2 contains PYD and HIN domains. Different inflammasomes are responsive to specific stimuli. Upon activation, inflammasome complexes are assembled and active caspase-1 is produced, which processes pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 to mature IL-1β and IL-18.

Table 1. Inflammasomes are presenting in various cell types and are associated with various disease outcomes.

| Cell type | Inflammasome | Disease outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Astrocytes | NLRP1[31] | CNS diseases[31] |

|

| ||

| Dendritic cells | NLRP1[18] | Anthrax disease[18] |

| IPAF[19] | Regulation of noncognate effector function[19] | |

| AIM2[20] | Tularemia[20] | |

| NLRP3[21] | Type II diabetes[59] | |

|

| ||

| Epithelial cells | NLRP3[32] | Chlamydial infection[32] |

|

| ||

| Fibroblasts | AIM2[33] | Periodontal disease[33] |

| NLRP3[33] | Periodontal disease[33] | |

|

| ||

| Macrophages | NLRP1[22] | Anthrax disease[18] |

| IPAF[23] | Gram-negative bacterial infection[114] | |

| AIM2[24] | Tularemia[20] | |

| NLRP3[25] | Gout,[45] Lung silicosis,[58] Lung fibrosis[46] | |

|

| ||

| Mast cells | NLRP3[26] | Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS)[26] |

|

| ||

| Microglial cells | NLRP3[27] | Alzheimer's disease[27] |

|

| ||

| Monocytes (primary) | NLRP1[28] | N/A |

| AIM2[30] | Tularemia[30] | |

| NLRP3[29] | Autoimmune diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus)[115] | |

|

| ||

| Neurons | NLRP1[31] | Traumatic brain injury (TBI)[116] |

|

| ||

| Keratinocytes | NLRP1[34] | Muckle-Wells Syndrome[34] |

| AIM2[35] | Lesional psoriasis vulgaris (PSV) on skin[35] | |

| NLRP3[36] | Inflammatory skin disease[117] | |

Table 2. Activators of inflammasomes.

| Inflammasome | Activators |

|---|---|

| NLRP1 | Anthrax lethal toxin[22, 37] |

| Muramyl dipeptide (MDP)[38] | |

|

| |

| IPAF | Gram-negative bacteria[39, 40] |

|

| |

| AIM2 | dsDNA[24, 118] |

|

| |

| NLRP3 | Bacterial pore-forming toxins[119] |

| Glucose[120] | |

| Oligomers of islet amyloid polypeptide[59] | |

| Amyloid-β[27] | |

| Viruses[121] | |

| Asbestos [12] | |

| Quartz[43] | |

| Alum[44] | |

| ATP[42] | |

| MSU[45] | |

| UV radiation[34] | |

| ENMs (Ag,[68] CeO2,[48] CNTs,[46, 101] HAP,[66] Polystyrene,[63, 67] TiO2,[47, 103] SiO2[49]) | |

Figure 2. Stimuli for NLRP3 inflammasome activation and NLRP3 inflammasome-associated diseases.

NLRP3 inflammasome is activated through a wide range of stimuli including pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), metabolic products, environmental hazards including engineered nanomaterials (ENMs). The activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and subsequent secretion of IL-1β have been associated with many diseases including asbestosis, silicosis, gout, Alzheimer's disease, inflammatory bowel disease, type II diabetes, and cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS).

3. NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation Induced by ENMs

Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome involves coordinated processes between stimuli and cells. Based on in vitro studies, it has been demonstrated that two signals are generally required to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome.[15] For signal 1, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) molecule is recognized by Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) residing on cell membrane, which further leads to NF-κB activation through adaptor protein MyD88, and increases the production of pro-IL-1β and NLRP3 proteins.[64] For signal 2, upon activation and assembly of NLRP3 inflammasome complex by various stimuli including particles, fibers, and ENMs, the pro-IL-1β is further processed to mature IL-1β (Figure 3). However, for in vivo inflammasome activation, it is not clear if signal 1 is needed.[65] After the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated, IL-1β and IL-18 are secreted, which further lead to the recruitment of other immune cells to the affected cells or tissues and the induction of clearance of nanomaterials. If the clearance is not successful, sustained NLRP3 inflammasome activation may result in chronic inflammation and subsequent tissue damage. The mechanisms of inflammasome activation induced by ENMs are not fully understood; however, more studies are suggesting that the physicochemical properties of ENMs including the ability to generate ROS, aspect ratio,[48, 66] dispersion state,[46] size[49, 67, 68] and surface functionalization[49, 63]could play major roles in NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Table 3). And the major mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation involve ROS, potassium (K+) efflux, lysosomal damage and subsequent cathepsin B release (Table 4).

Figure 3. Major mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

NLRP3 inflammasome activation requires two signals in vitro. For signal 1, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) is recognized by Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) residing on cell membrane, which further leads to NF-κB activation through adaptor protein MyD88, and the production of pro-IL-1β. For signal 2, upon the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome complex by various stimuli including metabolic products, environmental hazards, vaccine adjuvants and ENMs, the pro-IL-1β is further processed to mature IL-1β. NLRP3 inflammasome activation mechanisms include ROS generation, potassium efflux, lysosomal damage and cathepsin B release. After phagocytosis of particles, fibers, and ENMs, NADPH oxidase is activated to generate ROS. The over-production of ROS may cause the destabilization and permeabilization of lysosomes and cathepsin B release, which will initiate the inflammasome activation cascade. ROS production could also lead to oxidation of the redox-active thioredoxin (TXN) and its subsequent dissociation from thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP). The freed TXNIP could interact with NLRP3 and trigger a conformational change of NLRP3 and subsequent binding of adaptor protein ASC, which lead to the inflammasome activation and IL-1β release. Mitochondrion is another important source of ROS in cells. Over-production of mitochondrial ROS could cause the destabilization of lysosomes and release of cathepsin B, which then activates caspase-2 to cause mitochondrial permeabilization and cytochrome c release. Similarly, lysosomal enzymes such as cathepsin B can cleave Bid to its active form tBid; and another lysosomal protease, cathepsin D activates Bax to cause the mitochondrial rupture and cytochrome c release. Cytochrome c release will further induce mitochondrial ROS production and promote NLRP3 inflammasome activation. In addition, potassium efflux induced by particles and fibers could also induce cellular ROS production and NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Table 3. Physicochemical properties of ENMs that affect the NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Table 4. Proposed NLRP3 inflammasome activation mechanisms induced by ENMs.

| Phagocytosis | K+ efflux | ROS (NADPH oxidase) | ROS (Mitochondria) | Lysosome damage/Cathepsin B | P2X7 | Syk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag spheres[68] | + | + | - | + | + | - | - |

| Asbestos[12] | + | + | + | - | + | - | - |

| Monosodium urate[104, 105, 122] | + | + | + | + | + | - | + |

| Alum[43, 122] | + | + | + | + | + | - | + |

| Quartz[12, 43] | + | + | + | + | + | - | - |

| Poly (lactide-co-glycolide)[67] | + | + | - | - | + | - | - |

| Polystyrene nanosphere[63] | + | + | - | + | + | - | - |

| TiO2 nanosphere[36] | - | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| TiO2 nanobelt[47] | + | + | - | - | + | - | - |

| CeO2 nanorod[48] | + | + | - | - | + | - | - |

| Hydroxyapatite[66] | + | + | + | - | + | - | - |

| Multi-wall carbon nanotubes[46, 101] | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

3.1. ROS Induced by Nanomaterials Are Activators of NLRP3 Inflammasome

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive free radicals containing oxygen atoms, which are commonly found in the forms of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), cellular superoxide (O2•-), and hydroxyl radical (OH•) in biological systems.[69, 70] ROS is critical in cellular signal transduction in response to stress during physiological processes.[71] However, if the ROS generation is prolonged, over production of ROS will overwhelm the cellular anti-oxidant system to induce oxidative stress, cell damage and even cell death. ROS generation and oxidative stress have become the best-developed paradigms to explain the toxic effects of inhaled particles and fibers.[1] Recent studies have also demonstrated that ROS generated by NADPH oxidase[12] and mitochondria[72] play an important role in the NLRP3 inflammasome activation induced by particulates and ENMs.

Asbestos and silica are incidental fibers and particles that can become airborne and inhaled; and experimental evidence has shown that they could induce pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancer.[73] Recent studies have suggested that NLRP3 inflammasome activation is involved in the pathogenesis of these diseases, and have shed light on the mechanisms of inflammasome activation induced by particles and fibers. A study by Dostert et al. demonstrated that asbestos and quartz can be recognized by NLRP3 inflammasome, which leads to the secretion of proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β in both in vitro and in vivo models.[12] The inflammasome activation involves ROS, which is generated by NADPH oxidase after phagocytosis of particles. NADPH oxidase (NOX) is a transmembrane enzyme complex including membrane components (gp91phox, p22phox) and cytosol components (p67phox, p47phox, p40phox, and Rac-GTP binding protein). It functions to transfer electrons from NADPH to molecular oxygen to produce superoxide anions via the NOX catalytic subunit.[74] During the process of phagocytosis of invading microbes or particulates, cytosolic components including p67phox, p47phox, p40phox and Rac-GTP binding protein translocate to membrane and assemble with membrane components gp91phox and p22phox. Further, the phosphorylation of p67phox, p47phox and p40phox leads to the activation of NADPH oxidase that in turn catalyzes the reduction of molecular oxygen to produce superoxide, a precursor of hydrogen peroxide which will undergo further reactions to generate ROS for the clearance of engulfed invading microbes[75] (Figure 3). Long aspect ratio materials, such as asbestos, could induce “frustrated phagocytosis”, which triggers the activation of NADPH oxidase, ROS generation and oxidative stress.[12] Knockdown of the NADPH oxidase subunit p22phox significantly reduced the level of IL-1β production, and down-regulation of ROS detoxifying protein (thioredoxin) increased IL-1β secretion.[12] In addition, particles themselves could generate ROS because of their physicochemical properties. Quartz could lead to the formation of the superoxide radical because of its surface reactivity and metal impurity such as iron that can catalyze Fenton reaction.[1] And a recent study by Zhang et al. showed that overlapping of the conduction band energy levels of nanoparticles with the cellular redox potential could induce electron transfer, ROS generation and oxidative stress.[76] The over-production of ROS induced by particles and/or NADPH oxidase activation may cause oxidative stress in cells and ROS could also destabilize the phagosomal membrane, which will release enzymes including cathepsin B and D to initiate the inflammasome activation cascade that will be discussed in later section.

In addition to NADPH oxidase-induced ROS, recent studies have demonstrated that mitochondrion-induced ROS may also be involved in NLRP3 inflammasome activation induced by stimuli including metabolic product monosodium urate (MSU) crystals and popular vaccine adjuvant, alum.[72, 77, 78] Mitochondrion is the central site of cellular energy metabolism, and is an important source of ROS within most mammalian cells.[79, 80] The mitochondrial electron transfer-generated ROS accounts for about 1-3% of total oxygen consumed by the cells under normal physiological conditions.[81] However, under certain physiological and pathological conditions, up-regulation of ROS production in mitochondria could happen. Calcium (Ca2+) is an important regulator of mitochondrial function, and mitochondrial matrix Ca2+ overload can lead to enhanced generation of ROS due to Ca2+-induced tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle or nitric oxide synthase (NOS) or enhanced cytochrome c dislocation from mitochondrial inner membrane.[82] Mitochondrion is cell's energy source through synthesizing majority of the cellular ATP, and the depletion of ATP in cells could stimulate the production of mitochondrial ROS, followed by depolarization of mitochondrial membrane potential.[83] Also, K+ efflux through plasma membrane could cause the disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential.[84] ENMs, such as long aspect ratio nanomaterials (MWCNTs,[46] CeO2 nanowires [48] and TiO2 nanobelts[47]) or nanoparticles with surface functionalization and coating (SiO2[49] and polystyrene[63]) could induce these changes directly or indirectly, e.g. through plasma and lysosomal membrane damage, Ca2+ influx, K+ efflux, ATP depletion, as well as ROS generation by NADPH oxidase, leading to increased mitochondrial ROS production. Furthermore, studies have shown that ENMs could directly interact with mitochondria. For example, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) could induce a dose-dependent loss in mitochondria membrane potential and therefore a loss of the functionality of mitochondria.[85] Similarly, silver nanoparticles could also reduce mitochondrial membrane potential.[86] Cationic polystyrene nanoparticles could promote a dose-dependent calcium influx in mitochondria.[87] Also, there is evidence showing that ultrafine particles (< 0.15 µm) could localize inside mitochondria.[88] The ENMs-mitochondria interaction could cause the mitochondrial membrane disruption, mitochondrial membrane potential loss and subsequent ROS generation. Over-production of ROS by mitochondria could subsequently destabilize lysosome membrane and cause cathepsin B release, which can activate caspase-2 to promote further mitochondrial permeabilization and cytochrome c release.[89] In addition, released lysosomal enzymes such as cathepsin B can cleave Bid to its active form tBid; and another lysosomal protease, cathepsin D can activate Bax to cause mitochondrial rupture and cytochrome c release[90, 91] (Figure 3). Cytochrome c is a component of electron transfer chain in mitochondria and its release is a central event during the process of apoptosis that can lead to further ROS generation by mitochondria.[92, 93] These studies suggest that mitochondria-induced ROS can form a positive feedback loop of that can further enhance ROS generation. In supporting the role of mitochondrial ROS in NLRP3 inflammasome activation, Zhou et al. demonstrated that mitophagy/autophagy blockade leads to the accumulation of damaged, ROS-generating mitochondria, and this in turn activates the NLRP3 inflammasome.[72] Treatment of macrophages with NLRP3 activators leads to recruitment of resting NLRP3 from endoplasmic reticulum structures together with ASC to the perinuclear space where they co-localize with endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria organelle clusters. Through blocking the expression of voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) on the mitochondrial outer membrane, both ROS generation and inflammasome activation are suppressed.[72] Lunov et al. also showed mitochondrial damage and subsequent ROS production induced by amino-functionalized polystyrene nanoparticles could lead to oxidation of the redox-active thioredoxin (TXN) and its subsequent dissociation from thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP). The freed TXNIP could interact with NLRP3 and trigger a conformational change of NLRP3 and subsequent binding of adaptor protein ASC, which lead to the inflammasome activation and IL-1β release.[63] Additionally, a recent study by Shimada et al. demonstrated that oxidized mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) released during programmed cell death could bind to NLRP3 and lead to NLRP3 inflammasome activation; and both binding of oxidized mtDNA to the NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-1β production were inhibited in the presence of oxidized nucleoside 8-OH-dG.[94] These studies build a link between mitochondria and inflammasome activation. Collectively, ROS generated by ENMs, NADPH oxidase[12] and mitochondria[72] have been demonstrated to promote NLRP3 inflammasome activation induced by ENMs; and physicochemical properties of ENMs play an important role in mediating the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome.

3.2. Long Aspect Ratio ENMs-induced Lysosomal Damage and Cathepsin B Release Activates NLRP3 Inflammasome

Long aspect ratio ENMs, such as nanorods, nanotubes, and nanowires, have attracted greater attention due to their unique chemical, mechanical, electric, and optical properties and their applications in nanodevices. It is known that asbestos, long aspect ratio fibrillar metabolic products, such as fibrillar peptide amyloid-β[27] and monosodium urate (MSU) crystals[45] could activate NLRP3 inflammasome. Similarly, recent studies have suggested that long aspect ratio ENMs could also activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, which plays an important role in the generation of chronic granulomatous inflammation and fibrosis in murine lung.[46] Mechanistic studies revealed that NLRP3 inflammasome activation induced by long aspect ratio ENMs involves lysosomal damage, and subsequent cathepsin B release that provides a signal for the assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome.[46, 48] Cathepsin B is one type of lysosomal proteases; it maintains the normal metabolism of cells, specifically the intracellular protein catabolism.[95, 96] Cathepsin B also has other functions, its activity has been found to be higher in many human tumors,[97] and it has been linked to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease.[27] A study by Hornung et al. demonstrated that the rupture of lysosomal compartments induced by crystalline silica and aluminum salt crystals and subsequent leakage of lysosomal contents into cytosol could trigger NLRP3 inflammasome activation that is dependent on cathepsin B activity.[43] More interestingly, the lysosomal damage induced by hypertonic and hypotonic solutions treatment in the absence of stimuli could also induce inflammasome activation, which could be impaired by either inhibition of phagosomal acidification or cathepsin B activity.[43] However, the detailed mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation induced by cathepsin B either directly or indirectly remains to be clarified.[14]

Among all long aspect ratio nanomaterials, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are one of the most extensively studied materials that can induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation. CNTs are drawing greater attention because of their widely potential applications in electronics, optics, drug delivery and cancer therapy.[98, 99] However, the extensive use of CNTs also raises safety concerns.[100] One type of CNTs are needle-like long aspect ratio tubes that are tube aggregates resembling asbestos fibers. Palomaki et al. compared the effect of size and shape of CNTs on NLRP3 inflammasome activation using carbon black, short CNTs, long, tangled CNTs, long, needle-like CNTs, and crocidolite asbestos.[101] It's been demonstrated that needle-like CNTs activated NLRP3 inflammasome and induced the secretion of IL-α and IL-1β. Similar to asbestos, needle-like CNTs induced frustrated phagocytosis, lysosome damage and cathepsin B release. Also, Nagai et al. demonstrated that diameter and rigidity of CNTs also play an important role in their bioreactivity,[102] with thin needle-like MWCNTs (diameter ∼50 nm) being more cytotoxic, inflammogenic, and carcinogenic than thick MWCNTs (diameter ∼150 nm) of similar lengths. In spite of these findings, we do not consider these heavily agglomerated needle-like CNTs with diameter >30 nm as typical CNTs. Instead, for typical CNTs with diameter < 30 nm, we have to consider material dimensions (length, diameter and aspect ratio), suspension state, and surface catalytic properties are more likely contributors of CNT-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation.[8] To systematically dissect the proportional contribution of each property, in our UC CEIN and UCLA Center for Nanobiology and Predictive Toxicology (CNPT), we have recently established a MWCNTs library containing as-prepared (AP), purified (PD), and carboxylated (COOH) forms.[62] AP- and PD-MWCNTs are hydrophobic and COOH-MWCNTs are hydrophilic and negatively charged. In general, the NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β production induced by these nanotubes are in the order of AP > PD >> COOH, reflecting their difference in purity, hydrophobicity, and surface charge.[62] To clarify the role of CNT dispersion, we compared the effects of non-dispersed to dispersed CNTs using protein-based dispersant (a mixture of bovine serum albumin (BSA) and dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC)).[46] We showed that BSA-dispersed tubes induced increased lysosomal damage, cathepsin B release, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, IL-1β production, and lung fibrosis in mice compared to non-dispersed tubes. Interestingly, the profibrogenic effect of CNTs could be inhibited by Pluronic F108 (PF108) coating on CNTs. PF108 is a nonionic triblock copolymer composed by two hydrophilic poly (ethylene oxide) (PEO) chains and an interspersed hydrophobic poly (propylene oxide) (PPO) domain.[46] It could passivate the tube surface to form a protective “brush-like” layer that provides steric hindrance and interferes in tube aggregation as well as prevents lysosomal damage and cathepsin B release, therefore reducing the NLRP3 inflammasome activation, IL-1β production and lung fibrosis (Figure 4). This results demonstrated that PF108 coating could be considered as a promising safe-by-design feature for potential use of CNTs in nanoproducts or nanotherapeutics.[46]

Figure 4. NLRP3 inflammasome activation induced by MWCNTs and CeO2 nanowires.

NLRP3 inflammasome activation studies induced by MWCNTs and CeO2 nanorods have been performed in UC Center of Environmental Implications of Nanotechnology (UC CEIN) and the UCLA Center for Nanobiology and Predictive Toxicology (CNPT). Well-dispersed MWCNTs by BSA and DPPC could induce lysosomal damage, cathepsin B release and NLRP3 inflammasome activation without causing frustrated phagocytosis. However, MWCNTs coated by Pluronic F108 (PF108) decreases lysosomal damages, cathepsin B release and IL-1β production in THP-1 cells as compared to BSA-dispersed MWCNTs. The mechanism of the protective effects involves decrease in surface reactivity of CNTs by PF108 coating. For CeO2 nanorods, when their length is ≥200 nm and aspect ratio is ≥ 22, the CeO2 nanorods progressively induce more lysosomal damage, cathepsin B release and IL-1β production compared to spherical or short CeO2 nanorods. TEM and SEM showed that CeO2 nanorods formed stacking bundles, which could pierce through cell membrane, a feature that is known as “frustrated phagocytosis”. The CeO2 stacking bundles could also pierce through lysosomes and cause cathepsin B release and induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Although various long aspect ratio materials (asbestos, CNTs) have been shown to induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation, it is not clear what the critical lengths and aspect ratios are needed to induce this effect. To answer this question, we synthesized a ceria nanomaterial library with precisely controlled lengths and finely tuned aspect ratios.[48] The successful creation of a comprehensive CeO2 combinatorial library allows, for the first time, the systematic study of pure length and aspect ratio effect on lysosomal damage, cathepsin B release, NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β production. We showed that when the length of CeO2 nanorods is ≥200 nm and aspect ratio is ≥ 22, the CeO2 nanorods could progressively induce more lysosomal damage, cathepsin B release and IL-1β production in THP-1 cells.[48] SEM analysis showed that at the critical length of 200 nm, CeO2 nanorods formed micron-sized stacking bundles, which could pierce through cell membrane, a feature that is known as “frustrated phagocytosis”. We also found that the stacking bundles were capable of piercing through lysosomes (1.1-2.9 μm in diameter). The lysosome damage and following cathepsin B release induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β production (Figure 4). In addition, a separate study by Hamilton et al., demonstrated that the long fiber-shaped titanium dioxide nanobelts (60-300 nm in diameter and 15-30 µm in length) induced inflammasome activation and release of inflammatory cytokines through lysosomal damage and cathepsin B release while the spherical (60-200 nm in diameter) and short nanobelts (60-300 nm in diameter and 0.8-4 µm in length) did not.[47]

Similar shape effect on inflammasome activation has also been examined using hydroxyapatite (HAP).[66] It's been demonstrated that needle-shaped (0-25 µm) and irregular clump or rod (5-30 µm) HAP crystals stimulated significant proinflammatory cytokine production in macrophages, whereas spherical (0-25 µm) and large-sized HAP crystals (80-160 µm) exhibited minimal cytokine production. After cellular uptake, needle-shaped rigid HAP particles could pierce through the lysosome membrane, release lysosomal protease and induce the NLRP3 inflammasome activation. The suppressed IL-1β production in the presence of ROS and cathepsin B inhibitors suggested that reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation by NADPH oxidase and cathepsin B release are possible mechanisms involved in HAP-induced inflammasome activation.[66] In addition, in vivo experiments showed that HAP-induced inflammasome requires NLRP3, ASC and caspase-1 in the air pouch model of synovitis.[66]

3.3. Effect of ENM Size on NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation

Nanomaterial size is another critical factor in determining the bio-nano interactions.[1] As the size of a particle falls into the nanometer regime, it often exhibits very different properties than the bulk material due to its increased surface area, higher density of low-coordinated atoms, and/or quantum size effects caused by spatial confinement of electrons and holes within the particle, which could all lead to increased surface reactivity. The size effect of ENMs on NLRP3 inflammasome activation has been examined by several studies, though contradictory results were obtained. Sharp et al. compared polystyrene particles of 430 nm, 1 µm, 10 µm, and 32 µm in diameter in inducing IL-1β production in dendritic cells and demonstrated that smaller particles were more potent in promoting IL-1β production due to efficient uptake.[67] Winter et al. demonstrated that nano-sized TiO2 particles induced more potent inflammasome activation compared to macro-sized TiO2 particles.[103] Actin-dependent cellular uptake was essential for the induction of inflammasome, and ROS generation was proposed as possible mechanism of inflammasome activation induced by TiO2 particles.[103] Yang et al. compared the inflammasome activation in monocytes in response to silver nanoparticles (NPs) of 5, 28 and 100 nm in diameter.[68] 5 and 28 nm silver NPs induced potent inflammasome activation while 100 nm NPs did not. Studies using inhibitors suggested that mitochondrial superoxide, K+ efflux, and cathepsin release were possible mechanisms of inflammasome activation induced by silver nanoparticles.[68] In contrast, Morishige et al. compared the IL-1β production levels in THP-1 cells induced by unmodified amorphous silica particles (SPs) of different diameters between 30 and 1000 nm.[49] 1000 nm-sized SPs induced significantly higher IL-1β production while smaller SPs did not. In our opinion, size itself may not be the main factor that influences the NLRP3 inflammasome activation, other properties, including chemical composition, surface charge and functionalization could play important roles there.

3.4. Effect of ENM Surface Charge and Functionalization on NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation

Surface functionalization determines the hydrophobicity, lipophobicity and catalytic activity of ENMs. Nanomaterial surface group is a determinant factor for particle binding and wrapping by cell surface membrane as well as defining the possible route of endosomal uptake.[87] Studies have demonstrated that ENM surface functionalization could also determine the level of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Lunov et al. showed that amino-functionalized, but not carboxyl or nonfunctionalized polystyrene nanoparticles induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in human macrophages.[63] The possible mechanisms of inflammasome activation include: increased uptake of highly charged particles could cause the opening of ion channels and subsequent K+ efflux to compensate the charge imbalance;[14] cationic polystyrene nanospheres could promote a dose-dependent calcium influx in mitochondria and subsequent ROS generation;[87] and cationic nanoparticles could induce a proton sponge effect which ruptures the lysosomal compartment and releases lysosomal content.[7] Another study by Morishige et al. demonstrated that surface modification (with -COOH, -NH2, -SO3H, -CHO) of microsized 1000 nm silica particles showed significantly lower IL-1β production compared to non-modified particles.[49] This is because surface modification of silica nanoparticles reduced ROS production, lysosomal damage, and cathepsin B release. These studies suggest that nanoparticle surface charge and functionalization also play a role in NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

3.5. K+ Efflux Is a Common Activator of NLRP3 Inflammasome Induced by ENMs

NLRP3 inflammasome activation could be triggered by various stimuli and mechanisms that seem to have no obvious similarities. However, a study by Petrilli et al. has revealed that K+ efflux may be the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome.[104] Under in vitro conditions, NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and caspase-1 recruitment occur spontaneously at K+ concentrations below 70 mM, and is prevented at higher K+ concentrations. Stimuli such as metabolic products monosodium urate (MSU) crystals and calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) crystals could potentially disrupt membrane and allow the efflux of K+.105 Also, some stimuli, e.g., ATP released from damaged cells could activate endogenous K+ channels through purinergic receptor P2X ligand-gated ion channel 7 (P2X7) residing on cell membrane, which are able to lower cytosolic K+ levels and induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation.[42] Although how exactly the K+ efflux induces NLRP3 inflammasome activation is still not fully understood, there is study showing that K+ efflux could trigger ROS production in human granulocytes.[106] However, the source of ROS is still not clear. It's reasonable to hypothesize that K+ efflux induced by ENMs may mobilize other pathways including ROS to activate NLRP3 inflammasome.

In summary, ENMs could be the activators of NLRP3 inflammasome, and the degree of stimulation is dependent on the physicochemical properties of nanomaterials and the interaction between ENMs and biological systems that happens at the nano-bio interface. The physicochemical properties of ENMs that play major roles in NLRP3 inflammasome activation include length, aspect ratio, dispersion state, size, and surface functionalization, which may mobilize various molecular mechanisms including ROS generation, K+ efflux, lysosomal damage and cathepsin B release. There are increasing evidence showing that these different molecular mechanisms often work collaboratively rather than independently in response to ENM stimuli to activate NLRP3 inflammasome,[107] suggesting the roles of NLRP3 inflammasome as a master integrator of stimuli to induce inflammation.

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

NLRP3 inflammasome is a danger signal receptor that can respond to a wide range of exogenous stimuli including ENMs. To date, there are some studies showing the interaction of ENMs with NLRP3 inflammasome. However, we are facing rapid increases in the production of ENMs with novel physicochemical properties, and their effects on NLRP3 inflammasome activation remains largely unknown. To meet this challenge, we advocate a predictive toxicological approach adopted by our UC CEIN and CNPT centers with the goal to link ENM physicochemical properties to NLRP3 inflammasome activation.[8] Briefly, this approach involves the synthesis of well-characterized compositional and combinatorial ENMs libraries with specific properties including composition, size, charge, aggregation state, crystallinity, aspect ratio, length, and surface functionalization, which allows us to link the physicochemical properties of ENMs to NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Also, we need to improve the existing and develop new assays based on the mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation including ROS generation, K+ efflux, lysosomal damage and cathepsin B release, etc. In addition, where possible, we should develop the in vitro assays into high throughput format that can incorporate large ENMs libraries, multiple cell lines and time points to rapidly perform the screening. Finally, in silico models are needed to establish structure-activity relationships (SARs) that can be used to predict the ENMs-inflammasome interactions.

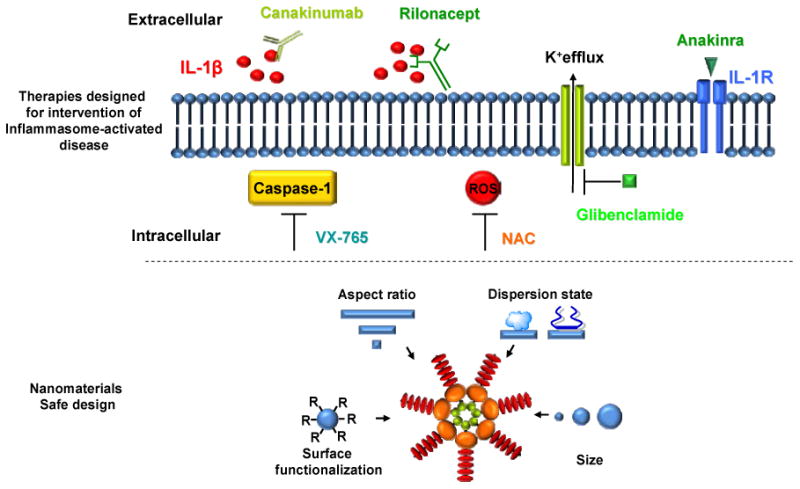

The mechanistic understanding of ENMs-inflammasome interaction could open new avenues for therapies targeting inflammasome-related diseases. To date, several promising drugs have been developed to neutralize IL-1β or interfere with the inflammasome activation pathways. These drugs include canakinumab, a human monoclonal antibody for IL-1β,[108] rilonacept, a fusion protein consisting of human IL-1 receptor extracellular domain and human IgG1 FC domain that binds and neutralizes IL-1;[109] glibenclamide, a K+ efflux inhibitor;[110, 111] anakinra, an IL-1 receptor antagonist;[112] and VX-765, a caspase-1 inhibitor[113]. Also, studies have demonstrated that N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), a pharmaceutical drug assisting in neutralizing damaging reactive oxygen species (ROS), is effective in inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation.[12, 27, 58] In addition, it is possible to modify ENM properties including aspect ratio, dispersion state, size and surface functionalization that could lead to safer ENMs with lower NLRP3 inflammasome activation potentials (Figure 5). Also, most of current knowledge of ENMs-inflammasome interaction is based on in vitro studies and only few in vivo models have been developed. Further exploration of molecular mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation induced by ENMs and its role in inflammation in both in vitro and in vivo models will broaden our knowledge and most importantly will facilitate safe design of nanomaterials and development of new intervention strategies for potential adverse health effects. Furthermore, NLRP3 inflammasome has been identified as a critical player in aluminum hydroxide- and aluminum phosphate-mediated adjuvant effects.[11, 44] As a result, inflammasome has been considered to play a role in the development of adaptive immunity. Better knowledge on the roles of inflammasome in adaptive immunity will provide a deeper understanding on material's adjuvant effect and will facilitate the development of new vaccines.

Figure 5. Intervention strategies for inflammasome activation associated biological effects.

Understanding of inflammasome activation mechanisms has been utilized to develop intervention strategies for inflammasome activation associated diseases. Canakinumab is a human monoclonal antibody that binds to IL-1β. Rilonacept is a fusion protein consisting of human IL-1 receptor extracellular domain and human IgG1 FC domain that binds and neutralizes IL-1. Glibenclamide is a potassium efflux inhibitor. Anakinra is an IL-1 receptor antagonist. VX-765 is caspase-1 inhibitor. N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) is an antioxidant that can neutralize ROS, and is a potential candidate for the treatment of inflammasome-related diseases. In addition, modification of ENM properties including aspect ratio, dispersion state, size and surface functionalization (R= COOH, NH2, PEG, SO3H) could lead to safer ENMs with lower NLRP3 inflammasome activation potentials.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US Public Health Service Grant U19 ES019528 (UCLA Center for NanoBiology and Predictive Toxicology) RC2 ES018766, RO1 CA133697, RO1 ES016746 as well as National Science Foundation and the Environmental Protection Agency under Cooperative Agreement Number DBI 0830117. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation or the Environmental Protection Agency.

References

- 1.Nel A, Xia T, Madler L, Li N. Science. 2006;311:622. doi: 10.1126/science.1114397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen X, Mao SS. Chem Rev. 2007;107:2891. doi: 10.1021/cr0500535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jain PK, Huang X, El-Sayed IH, El-Sayed MA. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1578. doi: 10.1021/ar7002804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colvin VL. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1166. doi: 10.1038/nbt875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oberdorster G, Oberdorster E, Oberdorster J. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:823. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donaldson K, Stone V, Tran CL, Kreyling W, Borm PJA. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61:727. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.013243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nel AE, Maedler L, Velegol D, Xia T, Hoek EMV, Somasundaran P, Klaessig F, Castranova V, Thompson M. Nat Mater. 2009;8:543. doi: 10.1038/nmat2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nel A, Xia T, Meng H, Wang X, Lin S, Ji Z, Zhang H. Acc Chem Res. 2012 doi: 10.1021/ar300022h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNeil SE. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2009;1:264. doi: 10.1002/wnan.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobrovolskaia MA, McNeil SE. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:469. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenbarth SC, Colegio OR, O'Connor W, Jr, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA. Nature. 2008;453:1122. doi: 10.1038/nature06939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dostert C, Petrilli V, Van Bruggen R, Steele C, Mossman BT, Tschopp J. Science. 2008;320:674. doi: 10.1126/science.1156995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strowig T, Henao-Mejia J, Elinav E, Flavell R. Nature. 2012;481:278. doi: 10.1038/nature10759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gross O, Thomas CJ, Guarda G, Tschopp J. Immunol Rev. 2011;243:136. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schroder K, Tschopp J. Cell. 2010;140:821. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen M, Wang H, Chen W, Meng G. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:549. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinon F, Mayor A, Tschopp J. The Inflammasomes: Guardians of the Body. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:229. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moayeri M, Sastalla I, Leppla SH. Microb Infect. 2012;14:392. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kupz A, Guarda G, Gebhardt T, Sander LE, Short KR, Diavatopoulos DA, Wijburg OLC, Cao H, Waithman JC, Chen W, Fernandez-Ruiz D, Whitney PG, Heath WR, Curtiss R, III, Tschopp J, Strugnell RA, Bedoui S. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:162. doi: 10.1038/ni.2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belhocine K, Monack DM. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:71. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01700.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghiringhelli F, Apetoh L, Tesniere A, Aymeric L, Ma Y, Ortiz C, Vermaelen K, Panaretakis T, Mignot G, Ullrich E, Perfettini JL, Schlemmer F, Tasdemir E, Uhl M, Genin P, Civas A, Ryffel B, Kanellopoulos J, Tschopp J, Andre F, Lidereau R, McLaughlin NM, Haynes NM, Smyth MJ, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L. Nat Med. 2009;15:1170. doi: 10.1038/nm.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newman ZL, Crown D, Leppla SH, Moayeri M. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;398:785. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu J, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Alnemri ES. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30:693. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9425-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hornung V, Ablasser A, Charrel-Dennis M, Bauernfeind F, Horvath G, Caffrey DR, Latz E, Fitzgerald KA. Nature. 2009;458:514. doi: 10.1038/nature07725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajamaki K, Lappalainen J, Oorni K, Valimaki E, Matikainen S, Kovanen PT, Eklund KK. Plos One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura Y, Kambe N, Saito M, Nishikomori R, Kim YG, Murakami M, Nunez G, Matsue H. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1037. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halle A, Hornung V, Petzold GC, Stewart CR, Monks BG, Reinheckel T, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Moore KJ, Golenbock DT. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:857. doi: 10.1038/ni.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gregory SM, Davis BK, West JA, Taxman DJ, Matsuzawa Si, Reed JC, Ting JPY, Damania B. Science. 2011;331:330. doi: 10.1126/science.1199478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pazar B, Ea HK, Narayan S, Kolly L, Bagnoud N, Chobaz V, Roger T, Liote F, So A, Busso N. J Immunol. 2011;186:2495. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi CS, Shenderov K, Huang NN, Kabat J, Abu-Asab M, Fitzgerald KA, Sher A, Kehrl JH. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:255. doi: 10.1038/ni.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silverman WR, Vaccari JPdR, Locovei S, Qiu F, Carlsson SK, Scemes E, Keane RW, Dahl G. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.004804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdul-Sater AA, Koo E, Haecker G, Ojcius DM. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:26789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.026823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bostanci N, Meier A, Guggenheim B, Belibasakis GN. Cell Immunol. 2011;270:88. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feldmeyer L, Keller M, Niklaus G, Hoh D, Werner S, Beer HD. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1140. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dombrowski Y, Peric M, Koglin S, Kammerbauer C, Goess C, Anz D, Simanski M, Glaeser R, Harder J, Hornung V, Gallo RL, Ruzicka T, Besch R, Schauber J. Science Translational Medicine. 2011;3 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yazdi AS, Guarda G, Riteau N, Drexler SK, Tardivel A, Couillin I, Tschopp J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:19449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008155107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyden ED, Dietrich WF. Nat Genet. 2006;38:240. doi: 10.1038/ng1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faustin B, Lartigue L, Bruey JM, Luciano F, Sergienko E, Bailly-Maitre B, Volkmann N, Hanein D, Rouiller I, Reed JC. Mol Cell. 2007;25:713. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki T, Franchi L, Toma C, Ashida H, Ogawa M, Yoshikawa Y, Mimuro H, Inohara N, Sasakawa C, Nunez G. PLoS Path. 2007;3:1082. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mariathasan S, Newton K, Monack DM, Vucic D, French DM, Lee WP, Roose-Girma M, Erickson S, Dixit VM. Nature. 2004;430:213. doi: 10.1038/nature02664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allen IC, Scull MA, Moore CB, Holl EK, McElvania-TeKippe E, Taxman DJ, Guthrie EH, Pickles RJ, Ting JPY. Immunity. 2009;30:556. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Newton K, McBride J, O'Rourke K, Roose-Girma M, Lee WP, Weinrauch Y, Monack DM, Dixit VM. Nature. 2006;440:228. doi: 10.1038/nature04515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, Samstad EO, Kono H, Rock KL, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:847. doi: 10.1038/ni.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kool M, Petrilli V, De Smedt T, Rolaz A, Hammad H, van Nimwegen M, Bergen IM, Castillo R, Lambrecht BN, Tschopp J. J Immunol. 2008;181:3755. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Nature. 2006;440:237. doi: 10.1038/nature04516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X, Xia T, Duch M, Ji Z, Zhang H, Li R, Sun B, Lin S, Meng H, Liao YP, Wang M, Song TB, Yang Y, Hersam M, Nel A. Nano Lett. 2012;12:3050. doi: 10.1021/nl300895y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamilton RF, Jr, Wu N, Porter D, Buford M, Wolfarth M, Holian A. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2009;6 doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-6-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ji Z, Wang X, Zhang H, Lin S, Meng H, Sun B, George S, Xia T, Nel A, Zink J. ACS Nano. 2012;6:5366. doi: 10.1021/nn3012114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morishige T, Yoshioka Y, Inakura H, Tanabe A, Yao X, Narimatsu S, Monobe Y, Imazawa T, Tsunoda Si, Tsutsumi Y, Mukai Y, Okada N, Nakagawa S. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6833. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salvesen GS, Dixit VM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:10964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.10964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mariathasan S, Monack DM. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:31. doi: 10.1038/nri1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dinarello CA. Blood. 1996;87:2095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gracie JA, Robertson SE, McInnes IB. J Leukocyte Biol. 2003;73:213. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0602313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dinarello CA, Cannon JG, Mier JW, Bernheim HA, Lopreste G, Lynn DL, Love RN, Webb AC, Auron PE, Reuben RC, Rich A, Wolff SM, Putney SD. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:1734. doi: 10.1172/JCI112495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Curtsinger JM, Schmidt CS, Mondino A, Lins DC, Kedl RM, Jenkins MK, Mescher MF. J Immunol. 1999;162:3256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sutton C, Brereton C, Keogh B, Mills KHG, Lavelle EC. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1685. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hirota SA, Ng J, Lueng A, Khajah M, Parhar K, Li Y, Lam V, Potentier MS, Ng K, Bawa M, McCafferty DM, Rioux KP, Ghosh S, Xavier RJ, Colgan SP, Tschopp J, Muruve D, MacDonald JA, Beck PL. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1359. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cassel SL, Eisenbarth SC, Iyer SS, Sadler JJ, Colegio OR, Tephly LA, Carter AB, Rothman PB, Flavell RA, Sutterwala FS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803933105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Masters SL, Dunne A, Subramanian SL, Hull RL, Tannahill GM, Sharp FA, Becker C, Franchi L, Yoshihara E, Chen Z, Mullooly N, Mielke LA, Harris J, Coll RC, Mills KHG, Mok KH, Newsholme P, Nunez G, Yodoi J, Kahn SE, Lavelle EC, O'Neill LAJ. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:897. doi: 10.1038/ni.1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kambe N, Nakamura Y, Saito M, Nishikomori R. Allergology International. 2010;59:105. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.09-RAI-0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lissner D, Siegmund B. The Scientific World Journal. 2011;11:1536. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2011.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang X, Xia T, Addo Ntim S, Ji Z, Lin S, Meng H, Chung CH, George S, Zhang H, Wang M, Li N, Yang Y, Castranova V, Mitra S, Bonner JC, Nel AE. ACS Nano. 2011;5:9772. doi: 10.1021/nn2033055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lunov O, Syrovets T, Loos C, Nienhaus GU, Mailänder V, Landfester K, Rouis M, Simmet T. ACS Nano. 2011;5:9648. doi: 10.1021/nn203596e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bryant C, Fitzgerald KA. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:455. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mayer-Barber KD, Barber DL, Shenderov K, White SD, Wilson MS, Cheever A, Kugler D, Hieny S, Caspar P, Nunez G, Schlueter D, Flavell RA, Sutterwala FS, Sher A. J Immunol. 2010;184:3326. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jin C, Frayssinet P, Pelker R, Cwirka D, Hu B, Vignery A, Eisenbarth SC, Flavell RA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111101108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sharp FA, Ruane D, Claass B, Creagh E, Harris J, Malyala P, Singh M, O'Hagan DT, Petrilli V, Tschopp J, O'Neill LAJ, Lavelle EC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804897106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang EJ, Kim S, Kim JS, Choi IH. Biomaterials. 2012;33:6858. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Nature. 2000;408:239. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Droge W. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:47. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kamata H, Hirata H. Cell Signal. 1999;11:1. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(98)00037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J. Nature. 2011;469:221. doi: 10.1038/nature09663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mossman BT, Bignon J, Corn M, Seaton A, Gee JBL. Science. 1990;247:294. doi: 10.1126/science.2153315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Babior BM. Blood. 1999;93:1464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sumimoto H. FEBS J. 2008;275:3249. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang H, Ji Z, Xia T, Meng H, Low-Kam C, Liu R, Pokhrel S, Lin S, Wang X, Liao YP, Wang M, Li L, Rallo R, Damoiseaux R, Telesca D, Mädler L, Cohen Y, Zink JI, Nel AE. ACS Nano. 2012;6:4349. doi: 10.1021/nn3010087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sorbara MT, Girardin SE. Cell Res. 2011;21:558. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Rathinam VAK, Lee SJ, Dolinay T, Lam HC, Englert JA, Rabinovitch M, Cernadas M, Kim HP, Fitzgerald KA, Ryter SW, Choi AMK. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:222. doi: 10.1038/ni.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Turrens JF. J Physiol (Lond) 2003;552:335. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chandel NS, McClintock DS, Feliciano CE, Wood TM, Melendez JA, Rodriguez AM, Schumacker PT. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001914200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM, Ames BN. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:10771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brookes PS, Yoon YS, Robotham JL, Anders MW, Sheu SS. Am J Physiol (Cell Physiol) 2004;287:C817. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00139.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Roy A, Ganguly A, BoseDasgupta S, Das BB, Pal C, Jaisankar P, Majumder HK. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1292. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.050161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.El Kebir D, Jozsef L, Khreiss T, Filep JG. Cell Signal. 2006;18:2302. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pulskamp K, Diabaté S, Krug HF. Toxicol Lett. 2007;168:58. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hussain SM, Hess KL, Gearhart JM, Geiss KT, Schlager JJ. Toxicol In Vitro. 2005;19:975. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xia T, Kovochich M, Liong M, Zink JI, Nel AE. Acs Nano. 2008;2:85. doi: 10.1021/nn700256c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li N, Sioutas C, Cho A, Schmitz D, Misra C, Sempf J, Wang MY, Oberley T, Froines J, Nel A. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:455. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Enoksson M, Robertson JD, Gogvadze V, Bu PL, Kropotov A, Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stoka V, Turk B, Schendel SL, Kim TH, Cirman T, Snipas SJ, Ellerby LM, Bredesen D, Freeze H, Abrahamson M, Bromme D, Krajewski S, Reed JC, Yin XM, Turk V, Salvesen GS. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008944200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bidere N, Lorenzo HK, Carmona S, Laforge M, Harper F, Dumont C, Senik A. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301911200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kushnareva Y, Murphy AN, Andreyev A. Biochem J. 2002;368:545. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cai JY, Jones DP. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shimada K, Crother TR, Karlin J, Dagvadorj J, Chiba N, Chen S, Ramanujan VK, Wolf AJ, Vergnes L, Ojcius DM, Rentsendorj A, Vargas M, Guerrero C, Wang Y, Fitzgerald KA, Underhill DM, Town T, Arditi M. Immunity. 2012;36:401. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Turk B, Turk D, Turk V. Biochim Biophys Acta, Protein Struct Mol Enzymol. 2000;1477:98. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00263-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mort JS, Buttle DJ. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29:715. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(96)00152-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Foghsgaard L, Wissing D, Mauch D, Lademann U, Bastholm L, Boes M, Elling F, Leist M, Jaattela M. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:999. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.5.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liu Z, Robinson JT, Tabakman SM, Yang K, Dai H. Mater Today. 2011;14:316. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Avouris P, Chen Z, Perebeinos V. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:605. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lam CW, James JT, McCluskey R, Arepalli S, Hunter RL. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2006;36:189. doi: 10.1080/10408440600570233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Palomaki J, Valimaki E, Sund J, Vippola M, Clausen PA, Jensen KA, Savolainen K, Matikainen S, Alenius H. ACS Nano. 2011;5:6861. doi: 10.1021/nn200595c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nagai H, Okazaki Y, Chew SH, Misawa N, Yamashita Y, Akatsuka S, Ishihara T, Yamashita K, Yoshikawa Y, Yasui H, Jiang L, Ohara H, Takahashi T, Ichihara G, Kostarelos K, Miyata Y, Shinohara H, Toyokuni S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E1330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110013108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Winter M, Beer HD, Hornung V, Kraemer U, Schins RPF, Foerster I. Nanotoxicology. 2011;5:326. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2010.506957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Petrilli V, Papin S, Dostert C, Mayor A, Martinon F, Tschopp J. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1583. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Schorn C, Frey B, Lauber K, Janko C, Strysio M, Keppeler H, Gaipl US, Voll RE, Springer E, Munoz LE, Schett G, Herrmann M. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.139048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fay AJ, Qian X, Jan YN, Jan LY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607914103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Davis BK, Ting JPY. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:105. doi: 10.1038/ni0210-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lachmann HJ, Kone-Paut I, Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Leslie KS, Hachulla E, Quartier P, Gitton X, Widmer A, Patel N, Hawkins PN, Canakinumab CSG. New Engl J Med. 2009;360:2416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hoffman HM, Throne ML, Amar NJ, Sebai M, Kivitz AJ, Kavanaugh A, Weinstein SP, Belomestnov P, Yancopoulos GD, Stahl N, Mellis SJ. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2443. doi: 10.1002/art.23687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Laliberte RE, Eggler J, Gabel CA. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.36944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lamkanfi M, Mueller JL, Vitari AC, Misaghi S, Fedorova A, Deshayes K, Lee WP, Hoffman HM, Dixit VM. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:61. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.So A, De Smedt T, Revaz S, Tschopp J. Arthrit Res Ther. 2007;9 doi: 10.1186/ar2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Stack JH, Beaumont K, Larsen PD, Straley KS, Henkel GW, Randle JCR, Hoffman HM. J Immunol. 2005;175:2630. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cai S, Batra S, Wakamatsu N, Pacher P, Jeyaseean S. J Immunol. 2012;188:5623. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Shin MS, Kang Y, Lee N, Kim SH, Kang KS, Lazova R, Kang I. J Immunol. 2012;188:4769. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Vaccari JPdR, Lotocki G, Alonso OF, Bramlett HM, Dietrich WD, Keane RW. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1251. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cho KA, Suh JW, Lee KH, Kang JL, Woo SY. Int Immunol. 2012;24:147. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxr110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Fernandes-Alnemri T, Yu JW, Datta P, Wu J, Alnemri ES. Nature. 2009;458:509. doi: 10.1038/nature07710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Craven RR, Gao X, Allen IC, Gris D, Wardenburg JB, McElvania-TeKippe E, Ting JP, Duncan JA. Plos One. 2009;4 [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zhou R, Tardivel A, Thorens B, Choi I, Tschopp J. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:136. doi: 10.1038/ni.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kanneganti TD, Ozoren N, Body-Malapel M, Amer A, Park JH, Franchi L, Whitfield J, Barchet W, Colonna M, Vandenabeele P, Bertin J, Coyle A, Grant EP, Akira S, Nunez G. Nature. 2006;440:233. doi: 10.1038/nature04517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Couillin Isabelle, Petrilli Virginie, Martinon F. The Inflammasomes. 2011 [Google Scholar]