Abstract

Leprosy is a chronic infectious condition caused by Mycobacterium leprae(M. leprae). It is endemic in many regions of the world and a public health problem in Brazil. Additionally, it presents a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, which are dependent on the interaction between M. leprae and host, and are related to the degree of immunity to the bacillus. The diagnosis of this disease is a clinical one. However, in some situations laboratory exams are necessary to confirm the diagnosis of leprosy or classify its clinical form. This article aims to update dermatologists on leprosy, through a review of complementary laboratory techniques that can be employed for the diagnosis of leprosy, including Mitsuda intradermal reaction, skin smear microscopy, histopathology, serology, immunohistochemistry, polymerase chain reaction, imaging tests, electromyography, and blood tests. It also aims to explain standard multidrug therapy regimens, the treatment of reactions and resistant cases, immunotherapy with bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine and chemoprophylaxis.

Keywords: Clinical evolution; Communicable disease prevention; Diagnosis, differential; Drug resistance; Education, continuing; Laboratory research; Leprosy; Mycobacterium leprae; Prognosis; Therapeutics

INTRODUCTION

Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae(M. leprae) and affects mainly skin and peripheral nerves. It is endemic in many regions of the world and a public health problem in Brazil. Additionally, it presents a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations dependent on the interaction of M. leprae with host and related to the degree of immunity to the bacillus. The diagnosis of this disease is a clinical one. However, in some situations laboratory exams are necessary to confirm the diagnosis of leprosy or classify its clinical form. Leprosy is cured by multidrug therapy (MDT), and standard therapy regimens are applied according to the operational classification established by the World Health Organization (WHO). The drugs used in the treatment are usually well tolerated and cases of relapse disease are rare. The prognosis for leprosy is good, as long as the patient has an early diagnosis and treatment; otherwise, sequelae may occur.1

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS

No laboratory test alone is considered enough to diagnose leprosy. Clinical data, complemented by semiological techniques such as evaluation of skin sensitivity and histamine or pilocarpine testing, usually conclude the diagnosis. In doubtful cases, Mitsuda intradermal reaction, smear and histopathology often make it possible to confirm the diagnosis of leprosy and classify its clinical form. Electroneuromyography and imaging tests, such as simple radiography, scintigraphy, ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging may help in the evaluation of peripheral neural involvement, thus assuming great importance in cases of neuritis and primary neural leprosy, in which sural nerve biopsy may also be helpful. The assessment the clinical and laboratory correlation between these imaging tests and blood tests is essential to detect the presence of systemic changes in reactional episodes and in advanced disease. New tools are currently available for specific cases or for research purposes, including serological tests with the phenolic glycolipid 1 antigen (PGL-1) and protein antigens; immunohistochemical reaction with antibodies against bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG), PGL-1 and S-100 protein; polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with several primers aiming at different genomic targets of M. leprae.2,3

Presently, the research priority is to identify molecular markers specific for M. leprae and develop sensitive laboratory tests to diagnose asymptomatic cases or those with few symptoms and to predict disease progression among exposed individuals, since early diagnosis and timely treatment are key elements to break the chain of leprosy transmission.

Intradermal reaction

Intradermal reaction consists of performing an intradermal injection of the lepromin antigen (synthesized from M. leprae) on the flexor surface of the forearm. There are two types of response: an early response, Fernandez reaction, which is assessed from 48 to 72 hours after injection and is considered positive if the onset of an erythema measuring between 10 and 20 mm is observed; and a delayed response, Mitsuda reaction, which is assessed 4 weeks after injection and is considered positive if the onset of a papule measuring 5 mm or more is observed. These two responses are not parallel between themselves, i.e., it is possible that only one of them is present. Mitsuda reaction expresses the level of cellular immunity and is the exteriorization of the tuberculoid granuloma observed in histopahological studies. Although the analysis of this reaction helps classify the clinical form of the disease, it does not allow making the diagnosis. Mitsude reaction is positive in tuberculoid patients, who show good cellular immune response, and negative in lepromatous patients, who have deficient response. In borderline patients, it was found that reaction positivity gradually decreases as cellular immune response decreases near the lepromatous pole and gradually increases as cellular immune response increases near the tuberculoid pole.4

Inoculation

M. leprae can be isolated from infected tissues after bacillus inoculation on the foot pad of mice, nine-banded armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus), athymic mice, and monkeys.5-8 It is a cumbersome and time-consuming technique that is employed only in referral centers. Additionally, it can be used to identify M. leprae and determine its viability outside the human body, select therapeutic and immunoprophylactic agents (vaccines), conduct studies to determine minimum inhibitory concentration and minimum effective dose of compounds against leprosy, and investigate the presence of resistant bacteria in relapsed cases. Currently, after the discovery of molecular detection techniques, the cultivation of bacillus in animals is almost limited to laboratories that investigate antimicrobial drugs. This resource is still useful in studies that aim to understand the biology of M. leprae and host-pathogen interaction.9

Skin smear microscopy

Skin smear microscopy is used to detect alcohol-acid resistant bacilli (AARB) in skin smears collected from standard sites (skin lesions, ear lobes, elbows). It is performed using the Ziehl Neelsen staining technique, which consists of staining bacilli with red dyes10 and makes it possible to assess the morphology index (MI) and the bacterial index (BI).

MI determines whether the bacillus is viable or not and is represented by the percentage of intact bacilli with regard to the total number of bacilli analyzed in the study. Intact (viable) bacilli are completely stained red and can be observed before treatment or in cases of relapsed disease. Fragmented bacilli show small gaps, due to the interruption in the synthesis of their components, while granular bacilli show great gaps with spots stained red. These two last types of bacilli comprise non-viable or killed microorganisms and are observed in treated patients.11

The BI represents the quantitative bacillary load (number of bacilli) and is expressed according to a logarithmic scale ranging from 0 to 6+. Smear is positive in the multibacillary group (MB), which helps establish a definite diagnosis of leprosy, but sensitivity is low in the paucibacillary group (PB), in which smear is often negative, with a limit of microscopy detection of 104 AARB bacilli per gram of tissue.11,12

Histopathology

Histopathological examination is usually performed in fragments of skin lesions or nerves. Hematoxylin-eosin staining should be complemented with Faraco-Fite staining or one of its variations for the investigation of AARB. Next, some histopathological characteristics are presented, according to the criteria established by Ridley and Jopling.13

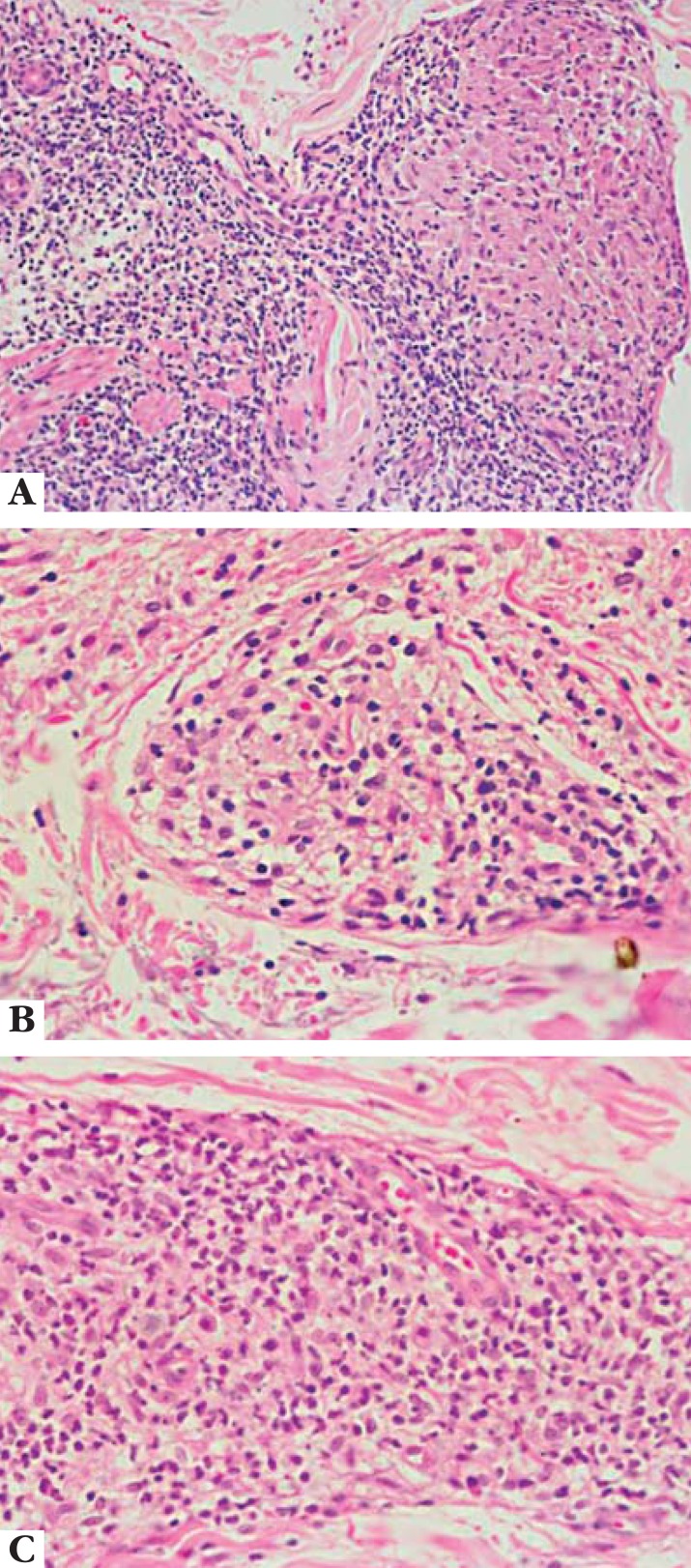

In the indeterminate group, a nonspecific inflammatory infiltrate is observed, with the predominance of lymphocytes. Diagnosis is suggested by periadnexal and perineural locations. The histopathological examination sometimes reveals that, despite disease clinical aspect, an evolution towards one of the poles may already be observed. There are no bacilli or they are scarce (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Indeterminate leprosy. Foci of non-granulomatous lymphohistocystic inflammatory infiltrate, selectively accompanying and/or penetrating nervous branches; HE, 100x. Archives of Lauro de Souza Lima Institute

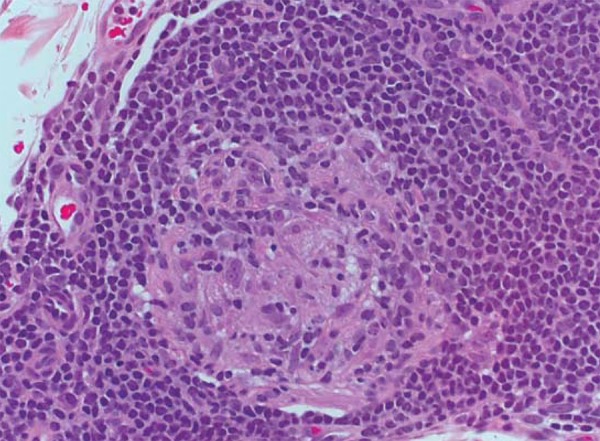

The tuberculoid-tuberculoid form (TT) presents with well-defined tuberculoid granulomas constituted by macrophages with epithelioid differentiation and Langhans multinucleated giant cells, as well as by lymphocytes in the center and surrounded by a dense lymphocytic halo. Granulomas extend from deep dermis to basal layer, with no bright area (free subepidermal grenz zone) (band of Unna), and may accompany nervous fillets, which are often destroyed by granulomas. There are no bacilli or they are scarce (Figure 2). These manifestations are an expression of good cellular immune response from the host.

FIGURE 2.

Tuberculoid leprosy. Granuloma of well differentiated epithelioid cells penetrated and circumvented by lymphocytes; HE, 400x. Archives of Lauro de Souza Lima Institute

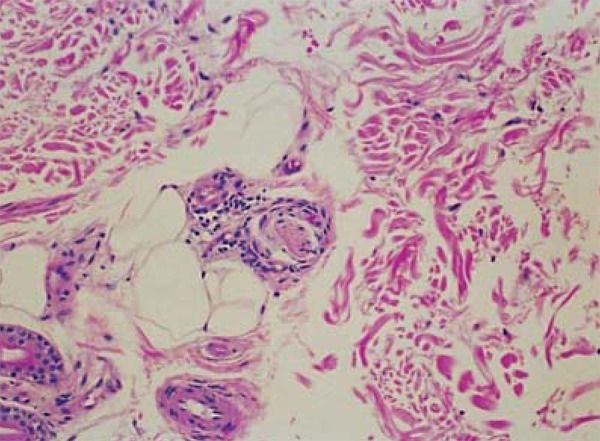

The lepromatous-lepromatous form (LL) presents with granulomas of hystocitic cells affecting hypodermis, with different levels of lipid change, forming vacuolated foamy cells (lepromatous cells) rich in bacilli, which may present in isolation or arranged in globi. Lymphocytes are scarce and sparse. Epidermis is flat and separated from the inflammatory infiltrate by a band of collagen fibers known as band of Unna, corresponding to the rectified papillary dermis (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Lepromatous leprosy. Extensive macrophagic granulomas, constituted by voluminous cells, presenting with homogeneous or slightly vacuolar cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei; HE, 400x. Archives of Lauro de Souza Lima Institute

The difference between a borderline group with higher resistance and another with lower resistance is based on progressive macrophage undifferentiation, on the decrease in the number of lymphocytes, and on the increase in the number of bacilli in granulomas and nerve branches.

The borderline-tuberculoid subgroup (BT) can be distinguished from the TT form due to the presence of free subepidermal grenz zone, and from the borderline-borderline subgroup (BB) due to the presence of granulomas formed by foci of epithelioid cells and Langhans multinucleated giant cells surrounded by lymphocytic halos. It is possible to observe strongly infiltrated but discernible nerve fibers (Figure 4). There are no bacilli or they are scarce, ranging from + to ++.

FIGURE 4.

Borderline leprosy (A: BT; B: BB; C: BL). Granulomatous reaction with progressive undifferentiation of macrophages, and reduction in number of lymphocytes through the DT to DV subgroups; HE, 400x. Archives of Lauro de Souza Lima Institute

The BB subgroup shows well developed epithelioid cells dispersed throughout the granulomas, no foci of lymphocytes, and scarce Langhans multinucleated giant cells and lymphocytes. Nervous fibers can be easily identified, exhibiting moderate proliferation of Schwann cells (Figure 4). The BI is greater, ranging from +++ to ++++.

The borderline-lepromatous (BL) subgroup shows undifferentiated macrophages and few lymphocytes or, most commonly, histiocytes with a trend to vacuolation, dense areas of perineural or granulomatous lymphocytic infiltration, and few changes in nerve fibers. There is a great number of bacilli (+++++) and not many globi. The free subepidermal grenz zone is maintained (Figure 4).

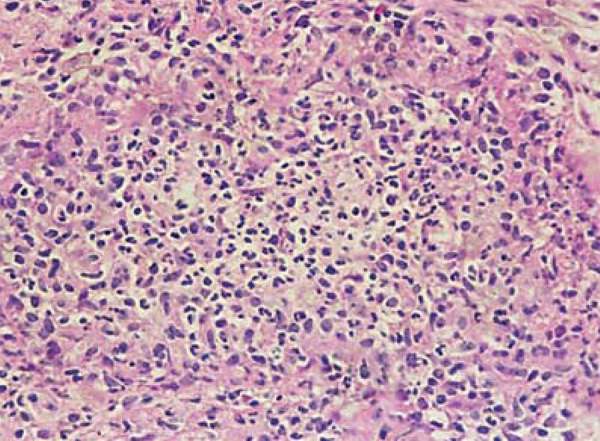

Extracellular edema may be observed in type 1 leprosy reactions. In the reverse reaction, granulomas become more organized and there is an increase in the number of lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and giant cells. A reduction in bacillary load and decrease or disappearance of intact bacilli can be observed, but neural aggression is greater and may lead to caseous necrosis (Figure 5). In the degradation reaction, granulomas become more loose and there is an increase in the amount of intact bacilli. The degeneration of elastic and collagen fibers may occur, as well as the presence of foci of necrosis in the granulomas and fibrinoid necrosis in the collagen.14

FIGURE 5.

Type 1 reaction. More extensive, confluent and poorly delimited granulomas; presence of interstitial and intracellular edema and multinucleated giant cells; HE, 400x. Archives of Lauro de Souza Lima Institute

Erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) may lead to vasodilation, exudation of polymorphonuclear neutrophils in previously infiltrated tissues, and predominance of granular bacilli (Figure 6). Intravascular thrombi may be found in necrotizing ENL.14

FIGURE 6.

Type 2 reaction. Acute inflammatory reaction presenting with a serofibrinous and neutrophilic exudation results in disorganization of pre-existing granulomas and formation of microabscesses; HE, 400x. Archives of Lauro de Souza Lima Institute

Serological testing

A laboratory test that can be easily performed, has low cost, and detects specific antibodies against M. leprae would be very helpful in field work, because most leprosy patients did not show visible changes and existing laboratory resources are usually not available. In order to find this test, researchers have been looking for the ideal serological test.

Several immunodominant antigens of M. leprae capable of activating specific B lymphocyte clones have been described, but so far the best standardized and more assessed test uses PGL-1, which has an antigenically specific trisaccharide of M. leprae. This antigen was initially described by Brennan & Barrow in 1980 and was used in serological studies on leprosy for the first time by Payne et al. in 1982.15,16 Due to its glycolipid nature, humoral immune response induces the production of antibodies without the participation of T lymphocyte with isotypes predominantly formed by immunoglobulin M (IgM). Subsequently, PGL-1 was synthesized as mono-, di- and trisaccharide compounds, and currently it is used by means of the immunoenzymatic assay (ELISA), passive hemagglutination test, hemagglutination in gelatin particles, dipstick, and rapid lateral flow test (ML flow).17 ML flow is a rapid test to be used in field work that showed 91% of agreement with the ELISA method, sensitivity of 97.4% in correctly classifying multibacillary (MB) patients, and specificity of 90.2%.18

The presence of anti-PGL-1 antibodies reflects bacillary load and helps classify clinical forms, since MB patients show high antibody titers and paucibacillary (PB) patients show scarce or absent titers, with a percentage of PGL-1 seropositive patients ranging from 80-100% in cases of lepromatous leprosy and 30-60% in those of tuberculoid leprosy.19-21 Therefore, the diagnostic value of the ML flow test is limited in PB leprosy. High levels of indeterminate leprosy seem to be associated with evolution towards the lepromatous pole.22

High levels of anti-PGL-1 antibodies are found in reactional episodes.23,24 When present at the beginning of the treatment, these antibodies indicate risk for type 1 reaction.25

During therapy monitoring, the decrease in antiPGL-1 antibodies is accompanied by antigen clearance and is correlated with bacterial indexes; persistence may represent resistance to therapy; and increase in PGL-1 antibodies in treated individuals indicates relapsed disease.23,26 However, as PGL-1 antigen is not soluble in water, it remains in tissues for a long time, which stimulates the production of IgM antibodies in the absence of viable bacilli.27 Therefore, the presence of anti-PGL-1 antibodies does not always mean active disease, since it may correspond to previous infection.28

Serological tests with PGL-1 antigen may identify individuals with subclinical infection, showing that seropositive contacts present a 7.2 times higher risk to develop leprosy than seronegative contacts, especially the MB form of the disease (24 times higher risk).29,30 In highly endemic areas, distribution of PGL1 positivity in leprosy cases is similar between household contacts and non-household contacts, but there is a significant difference between contacts and non-contacts in areas of low endemicity.31 However, there is no cutoff point for anti-PGL-1 levels to distinguish between subclinical infection and disease, both in the healthy population and in leprosy patients.32 Thus, the investigation for IgM antibodies against PGL-1 should not be the only population screening tool to detect leprosy cases, but seropositive individuals should be followed up.26,33 Notwithstanding, not all seropositive individuals will develop the disease.28

In the Brazilian population, the detection of IgG and IgA antibodies in rapid anti-PGL-1 tests, in addition to the detection of IgM antibodies, did not increase sensitivity nor did it influence performance in the serological test among patients with PB and MB leprosy.34

More recently, studies on the genomic sequences of M. leprae identified proteins and peptides specific for this bacillus and tested its immunoreactivity in leprosy patients and their contacts, through the detection of antigen-specific G immunoglobulins (IgG) of several recombinant proteins of M. leprae.35-38 Serological studies with these proteins, as well as those with PGL-1 antibodies, reflect spectral concept of leprosy, with high antibody titers in the lepromatous pole and low or absent titers in the tuberculoid pole.

Antigenic differences or differences in the human leukocyte antigen of strains of M. leprae seem to have an influence on antigen immunogenicity, resulting in different serological patterns among the countries in which proteins were studied. The most seroreactive recombinant proteins were ML0308 in South Korea and ML0405 and ML2331 in Brazil, the Philippines, and Venezuela; additionally, ML0678, ML0757, ML2177, ML2244 and ML2498 showed to be strong epitopes of B cells in Mali and Bangladesh. Combining these proteins with PGL-1 improves test specificity and sensitivity.35-38

The Infectious Disease Research Institute, located in Seattle, USA, developed a fusion protein that incorporated ML0405 and ML2331 antigens, known as LID-1. This protein was found to have high specificity in a hyperendemic area of Venezuela and in Brazil, maintaining the immunoreactivity of the original proteins. Furthermore, it is being tested for the rapid diagnosis of leprosy.37

ML0405, ML2331 and LID-1 were efficient in detecting new cases. Responses against these antigens has been shown to be correlated with bacillary load and clinical forms at the time of diagnosis.37 It was also found that the levels of circulating anti-LID-1, anti-ML0405 and anti-ML2331 IgG antibodies decreased both in MB and PB patients (more rapidly in PB patients) during treatment, which suggests that the serological analysis of these proteins is useful to evaluate treatment efficacy and disease relapsed.39

Currently, studies has been focusing on serological diagnosis based on the cell immune response to candidate antigens of M. leprae (recombinant proteins and peptides) as assessed by the measurement of the production of gamma interferon (IFN-γ), an indirect indicator of protective cellular immunity. This method may detect earlier evidence of infection by M. leprae and diagnose PB cases. Both peripheral mono-nuclear cells and whole blood have been successfully used in this type of serological test. In general, studies on leprosy based on immune cellular response show that cell stimulation with selected antigens induces a higher IFN-γ production in MB within-household contacts and in PB patients. Other current studies also aimed to identify indirect markers of protective immunity other than IFN-γ.40

Immunohistochemical reaction

Immunohistochemical reaction using monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies to detect M. leprae antigens may provide higher sensitivity and specificity than conventional methods, representing an important auxiliary tool in the diagnosis of leprosy, especially at the initial phases or in PB cases.41-48 Additional advantages of this technique include the fact that it is not dependent on bacillary viability and preserves tissue morphology, which makes it possible to determine bacillus location in the tissues.47,49

Several antibodies are used in the diagnosis of leprosy, such as those directed against proteins (e.g. S100 and heat shock proteins like 35 kDa and 65 kDa), and against lipoarabinomannan and PGL-1 glycolipids.27,45,46,50-52 Except for anti-PGL-1 antibody, which is directed against an antigen specific for M. leprae, the remaining antibodies may produce positive results in normal human skin or in some chronic and autoimmune infectious diseases.27

Taking advantage of the cross reaction between mycobacterium antigens, the anti-BCG antibody has also been used to demonstrate M. leprae in the tissues of individuals with leprosy.39-43,46-48,53, 54

The antibody against S-100 protein, a molecule expressed in the peripheral nervous system, may demonstrate remnants of dermal nerves and inflammatory infiltrate neurotropism in skin fragments.47,55,56 Additionally, the positive staining may make it possible to exclude leprosy if it shows intact nerve endings in granulomatous diseases of other etiology.57

Molecular identification of M. leprae bacillus

PCR allows detecting slow growth or uncultivable microorganisms, and, based on the available genetic data, has been used to detect M. leprae, since 1989.58-60

PCR made it possible to detect, quantify and determine M. leprae viability, showing significantly better results compared to common microscopic examinations. It is based on the amplification of specific sequences of M. leprae genome and in the identification of the fragment of amplified deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) or ribonucleic acid (RNA).60 However, this technique is limited to research centers, due to the high cost of reagents and to the need of specific equipment and qualified professionals.

Among its many utilities, PCR may allow confirming cases of initial, PB and pure neural leprosy; demonstrating subclinical infection in contacts; monitoring treatment; determining patients' cure or their resistance to MDT drugs; distinguishing reaction from recurrence; and help understand the mechanisms of M. leprae transmission.61-67

The investigation of M. leprae by PCR has been conducted in different types of samples, such as smear, biopsy fragment, or skin biopsy imprint; nasal swab; fragment of nasal concha biopsy; swab or fragment of oral mucosa biopsy; urine; nerve; blood; lymph node; and hair.63,65,68-75

Several factors may interfere with detection rates, such as the different primers aiming at different genomic targets of M. leprae, the size of amplified fragments, and the amplification technique used in the investigation are.60.61

Primers that amplify very large amplicons may reduce reaction positivity. Primers that amplify short amplicons have been successfully used, even in damaged DNA or at low concentrations, which demonstrates that amplicon size may be a limiting factor for the detection of M. leprae DNA.76

In addition to conventional PCR techniques, other techniques have been used to detect M. leprae, including nested-PCR, total genomic amplification, and real-time PCR.77-79 Reverse transcriptase PCR of M. leprae ribosomal RNA may determine bacillus viability.80 Real-time PCR allows achieving a rapid, sensitive and specific detection and quantification. However, it is little used in the context of leprosy, and there is controversy regarding its advantages over conventional techniques, since the literature shows reports of both better and similar results.78.79

IMAGING TESTS

Imaging tests may be useful in leprosy mainly to assess bone and joint involvement and peripheral nerve lesions.

Evaluation of bone and joint involvement

Although computed tomography (CT) is a more accurate test to analyze bone and joint lesions, especially those secondary to neurological involvement, a simple radiography may show many changes. The most common radiological findings are signs of osteomyelitis and resorption of the extremities such as hands and feet, causing loss of digits and neuropathic osteoarthropathy of the small joints, as well as osteopenic changes.81 Scintigraphy may help differentiate between active and inactive disease, because it allows performing a functional assessment of organs and systems, making it possible to analyze infection activity and evaluate therapeutic results. An example of changes that can be assessed by scintigraphy is the increase in arterial perfusion and abnormal focal radiopharmaceutical absorption in cases of hand and foot mutilations caused by osteomyelitis.82

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may more accurately reveal soft tissue changes, such as subcutaneous fat infiltration, cellulitis, and abscess, in addition to osteomyelitis and neuropathic osteoarthropathy. Thus, it is the test of choice for the early diagnosis of these disorders in clinically asymptomatic neuropathic feet.83-87

Evaluation of peripheral nerve involvement

The assessment of peripheral nerve changes by clinical examination is subjective and consists of comparing the nerve of interest with its contralateral nerve. It is a very difficult task in some nerves, such as the median nerve, because of their location. Ultrasound (US) and MRI provide a more accurate and objective evaluation.

US may evaluate thickening, structural anomalies, edema, and neural vascularization, in addition to identifying nerve abscess and compression. The cross-sectional area of the nerve may be measured in order to assess thickening. High resolution color Doppler US shows an increase in neural vascularization at the acute phase of neuritis in type 1 and 2 reactions, with greater signs of blood flow in perineural plexus or in intrafascicular vessels in type 1 reactions. When repetitive, these reactions may lead to hypoechoic changes in the epineurium and to fusiform edema in the fasciculi of thickened musculoskeletal nerves.83,88 In cases of advanced leprosy, structural anomalies may be observed, such as the lack of fascicular echotexture, and the absence of edema.81 Therefore, US is especially useful to monitor therapeutic responses of reactional neuritis when clinical evaluation becomes difficult and surgical decompression or neurolysis is recommended. Additionally, it may differentiate primary neural leprosy from other conditions affecting nerves, such as benign tumors, or conditions affecting neighboring structures, such as sinovial cysts and tenosynovitis, in cases of compressive syndromes.81

MRI is a supplementary tool in the differential diagnosis between leprosy neuropathy and other peripheral nerve diseases and has the advantage, compared to clinical neuropathophysiologic investigation and US, of not being dependent on an operator. It is used in specific cases, especially due to its high cost, and may show endoneural structural anomalies, thickening, nerve abscess, and compressive signs.89 Compared to US, which detects active type 1 reaction in 74% of the cases, MRI sensitivity is 92%, showing a contrast hypervascular enhancement pattern in acute neuritis.90

CT may also be used to diagnose peripheral nerve thickening in leprosy patients. The tissue adjacent to the peripheral nerve usually has different fat and tendon densities.91

In tuberculoid patients, simple radiographies sometimes reveal calcifications, especially on ulnar and fibular nerves, and thickened nerves. These calcifications are linear throughout the nerve or flake-shaped, but may also be oval-shaped as a result of perineural abscess. An injection of contrast throughout nerve sheaths may locate the calcification.91.92

Electroneuromyography

Electroneuromyography is indicated at the time of diagnostic evaluation in cases of suspected primary neural leprosy in order to help choose the site of nerve biopsy. During and after treatment, it is useful in cases of worsening of neurological function, especially in reactional neurites. In neurites, it helps in treatment monitoring and provides parameters for the indication of surgical treatment and for postoperative control. Almost all leprosy patients show electroneuromyographic changes, which are discreet in the indeterminate type of the disease, moderate in the tuberculoid form, and severe in borderline and lepromatous forms.93 Anomalies may occur even in individuals with normal neurological exams showing unthickened nerves.94 Electroneuromyographic changes include peripheral neurogenic involvement, with no evidence of disease in cells from the ventral horn of the spinal cord, usually leading to multiple mononeuropathy or, less commonly, to isolated mononeuropathy or distal polyneuropathy. In general, no changes are observed in the muscles not affected by leprosy.93 Paralyzed muscles showed good response to stimulation, which suggests evidence of axonal interruption without actual degeneration, a finding that was consistent with the involvement of Schwann cells or interstitial tissue.95 The most common and early finding is the decrease in the amplitude of motor and sensitive responses, which is usually more common than the decrease in the velocity of nerve conduction. The most frequently altered nerve seems to be the ulnar nerve, with the possible presence of cubital and carpal tunnel syndromes; however, a study demonstrated the involvement of the following nerves, in descending order of frequency: sural, median, ulnar, fibular, posterior tibial, and frontal branch of the facial nerve.93,94 In view of the multifocal involvement and the frequency of subclinical abnormalities, the study on nerve conduction should be extensive and cover the four limbs.

Blood changes

In the MB forms of leprosy, especially in the lepromatous form, there is a high prevalence of hematologic changes, such as hemolytic anemia, leukopenia and lynphopenia, and of immunological changes, including the presence of antinuclear factor, rheumatoid factor, anticardiolipin antibodies, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, often mimicking the clinical and laboratory picture of inflammatory diseases, such as those of the connective tissue.96-98

Additionally, low iron serum levels and slightly high ferritin serum concentrations may be observed, resulting from the disorganized iron transportation that is typically present in cases of anemia in patients with chronic disease.99 Lipid antigens are responsible for false positive reactions for syphilis.100 The concentration of C-reactive protein is significantly high in patients with ENL and arthritis compared to those without arthritis. Hemosedimentation velocity is high, but it is not associated with the increase in the concentration of C-reactive protein.99

In lepromatous patients at more advanced stages of leprosy, who may present with multisystemic involvement, it is important to perform a laboratory investigation directed to patient's complaints. In cases of suspected kidney involvement, blood urea and creatinine levels should be measured, and the presence of anemia, hypercalcemia, and metabolic acidosis should be investigated. Urinalysis should be performed with the purpose of seeking for changes in urinary concentration, leukocituria, proteinuria, and hematuria.101 Testicular involvement may lead to decrease in testosterone levels and increase in plasma estradiol, luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels. Hyperprolactinemia may be related to hypogonadism and hyperestrogenemia. Plasma cortisol levels are found to be high or normal in adrenal lesions. Exceptionally, reduced T3 and T4 levels are observed, especially in leprosy reactions.102 Liver enzymes, i.e., glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT) and glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (GPT) may be increased in type 2 reactions, but are rarely altered in type 1 reactions and in the chronic course of the disease.103.104

EVOLUTION AND PROGNOSIS

Indeterminate leprosy can cure spontaneously or evolve to one of the disease forms. After the disease is established, its course is chronic throughout the years, sometimes having asymptomatic periods that may be interrupted by exacerbation episodes (reactions), which are the main causes of disability.

The prognosis for leprosy is good, as long as the patient has an early diagnosis and treatment. Otherwise, it may lead to sequelae, especially neurological ones. Complications may also occur, resulting from reactions and from adverse effects caused by drugs used in the treatment, which can occasionally be severe and lead to death. Long-lasting lepromatous cases may result in the involvement of several organs.105

TREATMENT

There was no effective treatment for leprosy until 1942, with the development of sulfone. Due to the report of cases resistant to this drug, MDT started to be recommended by the WHO in 1982, and was extensively and officially established in Brazil in 1993. Therapeutic regimens are standardized according to operational classification and follow well established protocols set forth in the Directive no. 3.125 of 7 October 2010, issued by the Brazilian Ministry of Health.106 After the case is notified, drugs are provided free of charge for the patient. For PB cases, the treatment consists of 6 doses given in a period of up to 9 months, including, for adults, a supervised monthly dose of rifampicine (RFM) 600 mg and of dapsone (DDS) 100 mg and a self-administered daily dose of DDS 100 mg. For children, the recommended dose is 450 mg of RFM and 50 mg of DDS. MB cases are treated with 12 doses given in a period of up to 18 months using the same drugs mentioned in the previous regimen, but adding a monthly supervised dose of 300 mg of clofazimin (CFZ) and a self-administered daily dose of 50 mg of CFZ to the previous regimen. For children, the recommended monthly dose of CFZ is 150 mg, and the self-administered dose of 50 mg is given at alternate days. For children and adults weighing less than 30 kg, the doses should be adjusted according to weight: 10-20 mg/kg of RFM, 1.5 mg/kg of DDS, and 5 mg/kg of CFZ for the monthly dose and 1 mg/kg of CFZ for the daily dose. The disease transmission is interrupted immediately at the beginning of treatment.

In the case of contraindication to any of the drugs, ofloxacin and/or minocycline can be used as alternative drugs. Exceptionally, monthly doses of the ROM regimen are recommended (RFM 600 mg + ofloxacin 400 mg + minocycline 100 mg), 6 doses in PB patients and 24 doses in MB patients.106 Other fluorquinolones (such as pefloxacin, spafloxacin, and moxifloxacin), clarithromycin, rifapentine, linezolid, and fusidic acid have been tested.106.107

Adverse effects to these drugs are infrequent and are most usually related to DDS, including dyspeptic symptoms, hemolytic anemia (which is severe only in cases of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency), dapsone syndrome (skin rash, lymphadenomegaly, jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly, and lymphocitosis with atypical lymphocytes), hepatitis, erythroderma, agranulocytosis, and methemoglobinemia. CFZ causes skin pigmentation and dryness and may lead to severe gastrointestinal manifestations when given at high doses (such as those used in reactions), due to the deposition of crystals on the intestinal wall. RFM may cause dyspeptic symptoms, skin rash, influenza-like syndrome, thrombocytopenia, hepatitis, respiratory failure, and renal failure caused by interstitial nephritis or by acute tubular necrosis.108 In the case of a more severe reaction, MDT should be temporarily stopped and the physician should establish the appropriate treatment for each case.106

Treatment is not contraindicated during pregnancy and breastfeeding, although the occurrence of reactions is common in the third trimester of pregnancy and puerperium. In women of childbearing age, it should be taken into account that RFM may interact with oral contraceptives by reducing their action.106

In addition to MDT, it is important to take measures to evaluate and prevent physical disabilities and promote educational activities, including those related to self-care. After completing the regular treatment, patients are considered cured, regardless skin smear is negative or not. MB patients which did not show improvement should receive 12 additional doses.106

MDT should be maintained in cases of reaction, adding prednisone (1-1.5 mg/kg/day) in patients with type 1 reaction and thalidomide (100-400 mg/day) in patients with type 2 reaction. Doses should be reduced as the patient improves. Since thalidomide is contraindicated for women at childbearing age, due to its teratogenic potential, prednisone (1-1.5 mg/kg/day) is the most indicated drug for this population and others available options are pentoxifylline (400-1200 mg/day) and CFZ (200-300 mg/day). In cases of chronic or intermittent reaction, the presence of intestinal parasitosis, infections (including dental ones), and emotional stress should be investigated, and CFZ should be given at 300 mg/day for 30 days in combination with prednisone or thalidomide. Subsequently, this dose should be reduced by 100 mg every 30 days,106,109

Cases of neuritis are treated with prednisone (1-1.5 mg/kg/day); additionally, it is important to keep the affected limb at rest and monitor neural function. Uncontrollable neuritis should be treated with intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy (1g/day) for 3 days. Surgical neural decompression is indicated in cases of nerve abscess, neuritis unresponsive to clinical treatment, intermittent neuritis, or neuritis of the tibial nerve (which is usually a silent disease that shows poor response to corticosteroid therapy).106

Corticosteroid therapy is also recommended in cases of ENL, erythema polymorphous-like reaction, sweet-like syndrome, ocular lesions, reactive hands and feet, glomerulonephritis, orchiepididymitis, arthritis, and vasculitis.106 In situations in which corticosteroid therapy is indicated, a previous treatment for verminosis should be started and side effects should be monitored during corticosteroid use.106

Neuropathic pain resulting from sequelae of neuritis may be treated with tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline 25-300 mg/day and nortriptyline 10-150 mg/day, or with anticonvulsivants, such as carbamazepine 200-3000 mg/day and gabapentin 900-3600 mg/day.106

Disease relapse is rare after the patient is considered cured and usually occurs after five years. Clinical criteria are based on operational classification once the possibility of reaction is ruled out. Suspected cases include PB patients presenting with pain along nerve paths, new areas with altered sensitivity, new lesions and/or exacerbated previous lesions that have not responded to corticosteroid therapy for at least 90 days; or cases of delayed reaction. Similarly, are suspicious MB cases with skin new lesions and/or exacerbated previous lesions, new neurological changes unresponsive to treatment with thalidomide and/or corticosteroids given at the recommended posology, as well as positive skin smear microscopy, or delayed reactions, or presenting with an increase in BI by 2+ compared to that of the day of discharge. In these cases, the occurrence of drug resistance should be investigated.106

RESISTANCE TO MDT

Monotherapy, such as the isolated use of DDS, and irregular treatment are the main causes of emergence of resistant bacilli. Since M. leprae cannot be cultured, the sensitivity of this bacterium to drugs can only be tested on the foot pad of mice, which is a slow method. Currently, PCR based on sequence analysis is the technique of choice to understand the molecular events responsible for M. leprae resistance to MDT drugs and is conducted in referral centers. Resistance to RFM is associated with mutations in the rpoB gene, which codifies the β subunit of RNA polymerase. Resistance to ofloxacin is associated with mutation in the gyrA and gyrB genes, which codify the A subunit of DNA gyrase of several mycobacteria, including M. leprae. Resistance to DDS has been associated with three mutations in the folP1 gene of M. leprae at positions 157, 158 and 164, changing the positions of amino acids 53 and 55. It is important to rule out the possibility of reinfection, since people who are susceptible to the bacillus, even after being cured, remain at the place where they have been previously infected and have come in contact with possible sources of transmission. 110

In 1998, the Technical Consul tative Committee of WHO recommended the following regimen for adults with suspected resistance to RFM: daily doses of CFZ 50 mg, ofloxacin 400 mg, and minocycline 100 mg during 6 months, followed by daily doses of CFZ 50 mg, minocycline 100 mg or ofloxacin 400 mg for an additional period of at least 18 months.111 In 2009, the WHO Report of the Global Programme Managers' Meeting on Leprosy Control Strategy suggested the following doses: 400 mg of moxifloxacin, 50 mg of CFZ, 500 mg of clarithromycin, and 100 mg of minocycline daily for six months with a maintenance phase including moxifloxacin 400 mg, clarithromycin 1000 mg, and minocycline 200 mg once a month for an additional period of 18 months.112

PREVENTION

BCG vaccine

Currently, the main strategy for the prophylaxis of leprosy is early diagnosis and treatment, because there is no specific vaccine against M. leprae. However, BCG vaccine is recommended and widely used in endemic countries, with consistent evidence of its protection against leprosy.113-119 However, the magnitude of such protection is variable and may be higher among high-risk populations, such as family contacts, and in observational studies (60%) compared to experimental studies (41%).114 A BCG vaccine containing M. leprae killed by heat seems to be more effective, but this presentation has not been available for commercial use yet.116, 117

Apparently, BCG is better in preventing MB forms than PB forms, although this point of view is not unanimous, 114,115,118 with the displacement of leprosy cases from the MB pole to the PB pole, due to the increase in cellular immune response, which may even stimulate positive results in the Mitsuda test.119

However, who should be vaccinated is still a matter of debate, as well as when and how often vaccinations should be performed. It seems that protection is higher in individuals vaccinated at younger ages (below 15 years) and that the exposure to other mycobacteria may interfere with vaccine efficacy. Nevertheless, there seem to be no difference between individuals who were vaccinated once and those who were vaccinated twice or more. On the other hand, revaccination seems to provide additional protection to adults (not to children), in whom the efficacy of the first vaccine decreases with time. Although the protection obtained with BCG decreases over time, it may last for 30 years or more.114

In Brazil, one BCG dose is recommended for all within-household contacts with no or only one BCG scar, and no vaccine dose is recommended for those with two scars and individuals below 1 year who have already been vaccinated.106

Several studies demonstrate an increased risk for the onset of clinical manifestations of leprosy during the first year after taking the BCG vaccine. This fact may be explained by the possible manifestation of symptoms among asymptomatic infected individuals who would develop the disease later if they had not taken the vaccine. However, it is possible that BCG leads to the manifestation of symptoms among individuals who would not develop the disease if they had not taken the vaccine.114

The benefits of the combination between BCG and MDT in MB patients is controversial, especially in those with high BI. Some reports warns about the risk of the onset of reactions, especially type 1 reactions; other reports, in turn, show that, rather than causing reactions, immunotherapy may reduce the time of reactions and of treatment to achieve bacillary clearance.120,121

Maintaining BCG coverage in countries with high load of leprosy is a good strategy, because it seems to provide long-lasting protection. However, it should be noted that BCG may be an exacerbating factor when given to individuals infected with HIV, especially children.114

Genomic information about M. leprae, together with the identification of a large number of antigens, gene cloning, and tools for recombinant protein expression, opens the way for the development of new vaccines. However, in view of the success of MDT in eliminating leprosy, vaccines are not currently a practical alternative to prevent this condition.

Chemoprophylaxis

The use of chemoprophylaxis in contacts, especially in PGL-1 seropositive and Mitsuda negative individuals, seems to help in the prevention of new cases, but is a questionable measure that requires short and accessible therapeutic regimens. A meta-analysis found that RFM (single dose of 300 to 600 mg), DDS (50 or 100 mg once or twice a week for 2 years), or acedapsone (an intramuscular injection of 225 mg every 10 weeks for 7 months) are effective in reducing the incidence of leprosy in contacts of new disease cases.122

Recently, an additional immunoprophylactic effect was observed when BCG vaccine is combined with RFM in the prophylactic treatment of close contacts. While protection with RFM alone was estimated at around 58%, its protective effect raised to 80% when combined with BCG.123

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None.

Financial Support: None.

Work conducted at Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP); Hospital Regional de Presidente Prudente - Universidade do Oeste Paulista (HRPP- UNOESTE) - Presidente Prudente (SP), Brazil.

How to cite this article: Lastória JC, Morgado de Abreu MAM. Leprosy: review of the epidemiological, etiopathogenic, and clinical aspects - Part 2. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(3):389-403.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moschella SL. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of leprosy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:417–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goulart IM, Goulart LR. Leprosy: diagnostic and control challenges for a worldwide disease. Arch Dermatol Res. 2008;300:269–290. doi: 10.1007/s00403-008-0857-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodrigues LC, Lockwood DNj. Leprosy now: epidemiology, progress, challenges, and research gaps. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:464–470. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dharmendra, Loew J. The immunological skin tests in leprosy. Part II. The isolated protein antigen in relation to the classical Matsuda reaction and the early reaction to lepromin. 1942. 9pIndian J Med Res. 2012;136 following 502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy L, Ji B. The mouse foot-pad technique for cultivation of Mycobacterium leprae . Lepr Rev. 2006;77:5–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma R, Lahiri R, Scollard DM, Pena M, Williams DL, Adams LB, et al. The armadillo: a model for the neuropathy of leprosy and potentially other neurodegenerative diseases. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6:19–24. doi: 10.1242/dmm.010215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lahiri R, Randhawa B, Krahenbuhl J. Application of a viability-staining method for Mycobacterium leprae derived from the athymic (nu/nu) mouse foot pad. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:235–242. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45700-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh GP, Dela Cruz EC, Abalos RM, Tan EV, Fajardo TT, Villahermosa LG, et al. Limited susceptibility of cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) to leprosy after experimental administration of Mycobacterium leprae . Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:327–336. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katoch VM. The contemporary relevance of the mouse foot pad model for cultivating M. leprae. Lepr Rev. 2009;80:120–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miranda RN, Dechandt HS, Trauczynski O. Subsídios ao diagnóstico bacteriológico da hanseníase. An Bras Dermatol. 1991;66:117–118. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Vigilância Epidemiológica . Guia de procedimentos técnicos: baciloscopia em hanseníase. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2010. [acesso 19 out 2012]. 54 p. (Série A. Normas e Manuais Técnicos). Disponível em: http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/arquivos/pdf/guia_hanseniase_10_0039_m_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shepard CC, McRae DH. A method for counting acid-fast bacteria. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1968;36:78–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity. A five-group system. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1966;34:255–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahawita IP, Walker SL, Lockwood DNJ. Leprosy type 1 reactions and erythema nodosum leprosum. An Bras Dermatol. 2008;83:75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brennan PJ, Barrow WW. Evidence for species-specific lipid antigens in Mycobacterium leprae . Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1980;48:382–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Payne SN, Draper P, Rees RJ. Serological activity of purified glycolipid from Mycobacterium leprae . Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1982;50:220–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujiwara T, Hunter SW, Cho SN, Aspinall GO, Brennan PJ. Chemical synthesis and serology of disaccharides and trisaccharides of phenolic glycolipid antigens from the leprosy bacillus and preparation of a disaccharide protein conjugate for serodiagnosis of leprosy. Infect Immun. 1984;43:245–252. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.1.245-252.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bührer-Sékula S, Smits HL, Gussenhoven GC, van Leeuwen J, Amador S, Fujiwara T, et al. Simple and fast lateral flow test for classification of leprosy patients and Identification of contacts with high risk of developing leprosy. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1991–1995. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.5.1991-1995.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ananias MTP, Araújo MG, Gontijo ED, Guedes ACM. Estudo do antiPGL-1 em pacientes hansenianos utilizando técnica de ultramicroelisa. An Bras Dermatol. 2002;77:425–433. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barro RPC, Oliveira MLW. Detecção de anticorpos específicos para antígeno glicolipíde fenólico -1 do M. Leprae (anti PGL-1IgM): aplicações e limitações. An Bras Dermatol. 2000;75:745–753. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klatser PR. Serology of leprosy. Trop Geogr Med. 1994;46:115–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verhagen C, Faber W, Klatser P, Buffing A, Naafs B, Das P. Immunohistological analysis of in situ expression of mycobacterial antigens in skin lesions of leprosy patients across the histopathological spectrum. Association of mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan (LAM) and Mycobacterium leprae phenolic glycolipid-I (PGL-I) with leprosy reactions. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1793–1804. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65435-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chin-a-Lien RA, Faber WR, van Rens MM, Leiker DL, Naafs B, Klatser PR. Follow-up of multibacillary leprosy patients using phenolic glycolipid-I based ELISA. Do increasing ELISA-values after discontinuation of treatment indicate relapse? Lepr Rev. 1992;63:21–27. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.19920004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goulart IMB, Penna GO, Cunha G. Imunopatologia da hanseníase: a complexidade dos mecanismos da resposta imune do hospedeiro ao Mycobacterium leprae . Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2002;35:365–375. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822002000400014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roche PW, Theuvenet WJ, Britton WJ. Risk factors for type-1 reactions in borderline leprosy patients. Lancet. 1991;338:654–657. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91232-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Contin LA, Alves CJ, Fogagnolo L, Nassif PW, Barreto JA, Lauris JR, et al. Uso do teste ML-Flow como auxiliar na classificação e tratamento da hanseníase. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:91–95. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962011000100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meeker HC, Schuller-Levis G, Fusco F, Giardina-Becket MA, Sersen E, Levis WR. Sequential monitoring of leprosy patients with serum antibody levels to phenolic glycolipid-I, a synthetic analog of phenolic glycolipid-I, and mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1990;58:503–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cunanan A, Chan GP, Douglas JT. Risk of development of leprosy among Culion contacts. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1998;66:S78A–S78A. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moura RS, Calado KL, Oliveira MLW, Bührer-Sékula S. Sorologia da hanseníase utilizando PGL-I: revisão sistemática. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2008;41:11–18. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822008000700004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bazan-Furini R, Motta AC, Simão JC, Tarquínio DC, Marques W Jr, Barbosa MH, et al. Early detection of leprosy by examination of household contacts, determination of serum anti-PGL-1 antibodies and consanguinity. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2011;106:536–540. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762011000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Douglas JT, Cellona RV, Fajardo TT Jr, Abalos RM, Balagon MV, Klatser PR. Prospective study of serological conversion as a risk factor for development of leprosy among household contacts. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11:897–900. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.5.897-900.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fine PE, Ponnighaus JM, Burgess P, Clarkson JA, Draper CC. Seroepidemiological studies of leprosy in northern Malawi based on an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using synthetic glycoconjugate antigen. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1988;56:243–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cardona-Castro N, Beltrán-Alzate JC, Manrique-Hernández R. Survey to identify Mycobacterium leprae-infected household contacts of patients from prevalent regions of leprosy in Colombia. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2008;103:332–336. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762008000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stefani MM, Grassi AB, Sampaio LH, Sousa AL, Costa MB, Scheelbeek P, et al. Comparison of two rapid tests for anti-phenolic glycolipid-I serology in Brazil and Nepal. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2012;107:124–131. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762012000900019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aráoz R, Honoré N, Cho S, Kim JP, Cho SN, Monot M, et al. Antigen discovery: a postgenomic approach to leprosy diagnosis. Infect Immun. 2006;74:175–182. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.175-182.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reece ST, Ireton G, Mohamath R, Guderian J, Goto W, Gelber R, et al. ML0405 and ML2331 are antigens of Mycobacterium leprae with potential for diagnosis of leprosy. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:333–340. doi: 10.1128/CVI.13.3.333-340.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duthie MS, Goto W, Ireton GC, Reece ST, Cardoso LP, Martelli CM, et al. Use of protein antigens for early serological diagnosis of leprosy. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14:1400–1408. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00299-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aráoz R, Honoré N, Banu S, Demangel C, Cissoko Y, Arama C, et al. Towards an immunodiagnostic test for leprosy. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:2270–2276. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rada E, Duthie MS, Reed SG, Aranzazu N, Convit J. Serologic follow-up of IgG responses against recombinant mycobacterial proteins ML0405, ML2331 and LID-1 in a leprosy hyperendemic area in Venezuela. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2012;107:90–94. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762012000900015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stefani MMA. Desafios na era pós genômica para o desenvolvimento de testes laboratoriais para o diagnóstico da hanseníase. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2008;41:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mshana RN, Belehu A, Stoner GL, Harboe M, Haregewoin A. Demonstration of mycobacterial antigens in leprosy tissues. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1982;50:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mshana RN, Humber DP, Harboe M, Belehu A. Demonstration of mycobacterial antigens in nerve biopsies from leprosy patients using peroxidase-antiperoxidase immunoenzyme technique. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1983;29:359–368. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(83)90039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Narayanan RB, Ramu G, Sinha S, Sengupta U, Malaviya GN, Desikan KV. Demonstration of Mycobacterium leprae specific antigens in leprosy lesions using monoclonal antibodies. Indian J Lepr. 1985;57:258–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khanolkar SR, Mackenzie CD, Lucas SB, Hussen A, Girdhar BK, Katoch K, et al. Identification of Mycobacterium leprae antigens in tissues of leprosy patients using monoclonal antibodies. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1989;57:652–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huerre M, Desforges S, Bobin P, Ravisse P. Demonstration of PGL I antigens in skin biopsies in indeterminate leprosy patients: comparison with serological anti PGL I levels. Acta Leprol. 1989;7:125–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Narayanan RB, Girdhar BK, Malaviya GN, Sengupta U. In situ demonstration of Mycobacterium leprae antigens in leprosy lesions using monoclonal antibodies. Immunol Lett. 1990;24:179–183. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(90)90045-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barbosa Ade A, Júnior, Silva TC, Patel BN, Santos MI, Wakamatsu A, Alves VA. Demonstration of mycobacterial antigens in skin biopsies from suspected leprosy cases in the absence of bacilli. Pathol Res Pract. 1994;190:782–785. doi: 10.1016/s0344-0338(11)80425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Natrajan M, Katoch K, Katoch VM. Histology and immuno-histology of lesions clinically suspicious of leprosy. Acta Leprol. 1999;11:93–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pagliari C, Duarte MI, Sotto MN. Pattern of mycobacterial antigen detection in leprosy. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1995;37:7–12. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651995000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naafs B, Kolk AH, Chin A, Lien RA, Faber WR, Van Dijk G, Kuijper S, et al. Anti-Mycobacterium leprae monoclonal antibodies cross-react with human skin: an alternative explanation for the immune responses in leprosy. J Invest Dermatol. 1990;94:685–688. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12876264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang T, Izumi S, Butt KI, Kawatsu K, Maeda Y. Demonstration of PGL-I & LAM-B antigens in paraffin sections of leprosy skin lesions. Nihon Rai Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;61:165–174. doi: 10.5025/hansen1977.61.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van den Bos IC, Khanolkar-Young S, Das PK, Lockwood DN. Immunohistochemical detection of PGL-1, LAM, 30 kD and 65 kD antigens in leprosy infected paraffin preserved skin and nerve sections. Lepr Rev. 1999;70:272–280. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.19990030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takahashi MD, Andrade HF Jr, Wakamatsu A, Siqueira S, De Brito T. Indeterminate leprosy: histopathologic and histochemical predictive parameters involved in its possible change to paucibacillary or multibacillary leprosy. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1991;59:12–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schettini AP, Ferreira LC, Milagros R, Schettini MC, Pennini SN, Rebello PB. Enhancement in the histological diagnosis of leprosy in patients with only sensory loss by demonstration of mycobacterial antigens using anti-BCG polyclonal antibodies. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 2001;69:335–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fleury RN, Bacchi CE. S-100 protein and immunoperoxidase technique as an aid in the histopathologic diagnosis of leprosy. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1987;55:338–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singh N, Arora VK, Ramam M, Tickoo SK, Bhatia A. An evaluation of the S-100 stain in the histological diagnosis of tuberculoid leprosy and other granulomatous dermatoses. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1994;62:263–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mello ES, Melo IS. O papel da proteína S-100 no diagnóstico imunohistoquímico da forma tuberculóide da hanseníase. An Bras Dermatol. 1993;68:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hartskeerl RA, de Wit MY, Klatser PR. Polymerase chain reaction for the detection of Mycobacterium leprae . J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:2357–2364. doi: 10.1099/00221287-135-9-2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Woods SA, Cole ST. A rapid method for the detection of potentially viable Mycobacterium leprae in human biopsies: a novel application of PCR. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1989;53:305–309. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(89)90235-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roselino AM. Biologia molecular aplicada às dermatoses tropicais. An Bras Dermatol. 2008;83:187–203. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Santos GG, Marcucci G, Guimarães J, Júnior, Margarido LC, Lopes LHC. Pesquisa de Mycobacterium leprae em biópsias de mucosa oral por meio da reação em cadeia da polimerase. An Bras Dermatol. 2007;82:245–249. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Job CK, Jayakumar J, Williams DL, Gillis TP. Role of polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of early leprosy. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1997;65:461–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wichitwechkarn J, Karnjan S, Shuntawuttisettee S, Sornprasit C, Kampirapap K, Peerapakorn S. Detection of Mycobacterium leprae infection by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:45–49. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.45-49.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bezerra da Cunha FM, Werneck MC, Scola RH, Werneck LC. Pure neural leprosy: diagnostic value of the polymerase chain reaction. Muscle Nerve. 2006;33:409–414. doi: 10.1002/mus.20465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patrocínio LG, Goulart IM, Goulart LR, Patrocínio JA, Ferreira FR, Fleury RN. Detection of Mycobacterium leprae in nasal mucosa biopsies by the polymerase chain reaction. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2005;44:311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lini N, Shankernarayan NP, Dharmalingam K. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of Mycobacterium leprae DNA and mRNA in human biopsy material from leprosy and reactional cases. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58:753–759. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.007252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smith WC, Smith CM, Cree IA, Jadhav RS, Macdonald M, Edward VK, et al. An approach to understanding the transmission of Mycobacterium leprae using molecular and immunological methods: results from the MILEP2 study. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 2004;72:269–277. doi: 10.1489/0020-7349(2004)72<269:AATUTT>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bang PD, Suzuki K, Phuong le T, Chu TM, Ishii N, Khang TH. Evaluation of polymerase chain reaction-based detection of Mycobacterium leprae for the diagnosis of leprosy. J Dermatol. 2009;36:269–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cruz AF, Furini RB, Roselino AM. Comparison between microsatellites and Ml MntH gene as targets to identify Mycobacterium leprae by PCR in leprosy. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:651–656. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962011000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pontes ARB, Almeida MGC, Xavier MB, Quaresma JAS, Yassui EA. Deteccção do DNA de Mycobacterium leprae em secreção nasal. Rev Bras Enferm. 2008;61:734–737. doi: 10.1590/s0034-71672008000700013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martinez TS, Figueira MM, Costa AV, Gonçalves MA, Goulart LR, Goulart IM. Oral mucosa as a source of Mycobacterium leprae infection and transmission, and implications of bacterial DNA detection and the immunological status. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1653–1658. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morgado de Abreu MA, Roselino AM, Enokihara M, Nonogaki S, Prestes-Carneiro LE, Weckx LL, et al. Mycobacterium leprae is identified in the oral mucosa from paucibacillary and multibacillary leprosy patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014 Jan;20(1):59–64. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Parkash O, Singh HB, Rai S, Pandey A, Katoch VM, Girdhar BK. Detection of Mycobacterium leprae DNA for 36kDa protein in urine from leprosy patients: a preliminary report. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 46:200. 275–277. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652004000500008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Santos AR, Nery JC, Duppre NC, Gallo ME, Filho JT, Suffys PN, et al. Use of the polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of leprosy. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:170–172. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-2-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Almeida EC, Martinez AN, Maniero VC, Sales AM, Duppre NC, Sarno EN, et al. Detection of Mycobacterium leprae DNA by polymerase chain reaction in the blood and nasal secretion of Brazilian household contacts. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99:509–511. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762004000500009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goulart IM, Cardoso AM, Santos MS, Gonçalves MA, Pereira JE, Goulart LR. Detection of Mycobacterium leprae DNA in skin lesions of leprosy patients by PCR may be affected by amplicon size. Arch Dermatol Res. 2007;299:267–271. doi: 10.1007/s00403-007-0758-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Plikaytis BB, Gelber RH, Shinnick TM. Rapid and sensitive detection of Mycobacterium leprae using a nested-primer gene amplification assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1913–1917. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.1913-1917.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Martinez AN, Britto CF, Nery JA, Sampaio EP, Jardim MR, Sarno EN, et al. Evaluation of real-time and conventional PCR targeting complex 85 genes for detection of Mycobacterium leprae DNA in skin biopsy samples from patients diagnosed with leprosy. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3154–3159. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02250-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rudeeaneksin J, Srisungngam S, Sawanpanyalert P, Sittiwakin T, Likanonsakul S, Pasadorn S, et al. LightCycler real-time PCR for rapid detection and quantitation of Mycobacterium leprae in skin specimens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008;54:263–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Phetsuksiri B, Rudeeaneksin J, Supapkul P, Wachapong S, Mahotarn K, Brennan PJ. A simplified reverse transcriptase PCR for rapid detection of Mycobacterium leprae in skin specimens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2006;48:319–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pereira HLA, Ribeiro SLE, Ciconelli RM, Fernandes ARC. Avaliação por imagem do comportamento osteoarticular de nervos periféricos na hanseníase. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2006;46:30–35. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Braga FJ, Foss NT, Ferriolli E, Pagnano C, Miranda JR, de Moraes R. The use of bone scintigraphy to detect active Hansen's disease in mutilated patients. Eur J Nucl Med. 1999;26:1497–1499. doi: 10.1007/s002590050486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Slim FJ, Faber WR, Maas M. The role of radiology in nerve function impairment and its musculoskeletal complications in leprosy. Lepr Rev. 2009;80:373–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Maas M, Slim EJ, Akkerman EM, Faber WR. MRI in clinically asymptomatic neuropathic leprosy feet: a baseline study. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 2001;69:219–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maas M, Slim EJ, Heoksma AF, van der Kleij AJ, Akkerman EM, den Heeten GJ, et al. MR imaging of neuropathic feet in leprosy patients with suspected osteomyelitis. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 2002;70:97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Slim FJ, Hoeksma AF, Maas M, Faber WR. A clinical and radiological follow-up study in leprosy patients with asymptomatic neuropathic feet. Lepr Rev. 2008;79:183–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Slim FJ, Illarramendi X, Maas M, Sampaio EP, Nery JA, Sarno EN, et al. The potential role of magnetic resonance imaging in patients with Hansen's neuropathy of the feet: a preliminary communication. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2009;8:169–173. doi: 10.1177/1534734609345142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jain S, Visser LH, Praveen TL, Rao PN, Surekha T, Ellanti R, et al. High-resolution sonography: a new technique to detect nerve damage in leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3: doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hari S, Subramanian S, Sharma R. Magnetic resonance imaging of ulnar nerve abscess in leprosy: a case report. Lepr Rev. 2006;77:381–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Martinoli C, Derchi LE, Bertolotto M, Gandolfo N, Bianchi S, Fiallo P, et al. US and MR imaging of peripheral nerves in leprosy. Skeletal Radiol. 2000;29:142–150. doi: 10.1007/s002560050584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chauhan SL, Girdhar A, Mishra B, Malaviya GN, Venkatesan K, Girdhar BK. Calcification of peripheral nerves in leprosy. Acta Leprol. 1996;10:51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lichtman DM, Swafford AW, Kerr DM. Calcified abscess in the ulnar nerve in a patient with leprosy. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61:620–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.DeFaria CR, Silva IM. Electromyographic diagnosis of leprosy. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1990;48:403–413. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1990000400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Morgulis RF, Nóbrega JAM, Lima JGC. Estudo comparativo da evidência de alterações ao exame neurológico e eletromiográfico na hanseníase. Neurobiologia. 1988;51:31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brasil-Neto JP. Electrophysiologic studies in leprosy. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1992;50:313–318. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1992000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Atkin SL, el-Ghobarey A, Kamel M, Owen JP, Dick WC. Clinical and laboratory studies of arthritis in leprosy. BMJ. 1989;298:1423–1425. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6685.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Teixeira Jr GJA, Silva CEF, Magalhães V. Aplicação dos critérios diagnósticos do lúpus eritematoso sistêmico em pacientes com hanseníase multibacilar. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2011;44:85–90. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822011000100019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chao G, Fang L, Lu C. Leprosy with ANA positive mistaken for connective tissue disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:645–648. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lapinsky SE, Baynes RD, Schulz EJ, MacPhail AP, Mendelow B, Lewis D, et al. Anaemia, iron-related measurements and erythropoietin levels in untreated patients with active leprosy. J Intern Med. 1992;232:273–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1992.tb00583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ruge HGS, Fromm G, Fühner F, Guinto RS. Serological findings in leprosy. An investigation into the specificity of various serological tests for syphilis. Bull World Health Organ. 1960;23:793–802. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Silva Jr GB, Barbosa OA, Barros RM, Carvalho PR, Mendoza TR, Barreto DMS, et al. Amiloidose e insuficiência renal crônica terminal associada à hanseníase. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2010;43:474–476. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822010000400031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Leal AMO. Endocrine changes in leprosy. Medicina (Ribeirão Preto) 1997;30:340–344. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Moura AK, Melo BL, Brito AE, Loureiro WR, Valente NY, Naafs B, et al. Letters to the editor. High levels of liver enzymes in five patients with type 1 leprosy reaction. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:96–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Klioze AM, Ramos-Caro FA. Visceral leprosy. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:641–658. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Meneses S, Cirelli NM, Aranzazu N, Rondon Lugo AJ. Lepra visceral: presentacion de dos casos y revision de la literatura. Dermatol Venez. 1988;26:79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Portal.saúde.gov.br. Ministério da Saúde Portaria nº 3.125, de 07 de outubro de 2010. Aprova as Diretrizes para Vigilância, Atenção e Controle da hanseníase. [acesso 19 out 2012]. [Internet] Disponível em: http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/arquivos/pdf/portaria_n_3125_hanseniase_2010.pdf.

- 107.World Health Organization Report of the Global Programme Managers' Meeting on Leprosy Control Strategy. New Delhi, India, 20-22 April 2009. [cited 2012 mar 1]. Disponível em: http://203.90.70.117/PDS_DOCS/B4292.pdf.

- 108.Opromolla DVA. Terapêutica da hanseníase. Medicina (Ribeirão Preto) 1997;30:345–350. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Penna GO, Martelli CMT, Stefani MMA, Macedo VO, Maroja MF, Chaul A. Talidomida no tratamento do eritema nodoso hansênico: revisão sistemática dos ensaios clínicos e perspectivas de novas investigações. An Bras Dermatol. 2005;80:511–522. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sekar B, Arunagiri K, Kumar BN, Narayanan S, Menaka K, Oommen PK. Detection of mutations in folp1, rpoB and gyrA genes of M. leprae by PCR- direct sequencing--a rapid tool for screening drug resistance in leprosy. Lepr Rev. 2011;82:36–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.World Health Organization . WHO Expert Committee on leprosy: eighth report. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 1998. (WHO technical report series; no. 968). [Google Scholar]

- 112.World Health Organization . Report of the Global Programme Managers' Meeting on Leprosy Control Strategy; 2009 Apr 20-22; New Delhi, India. SEA-GLP-2009; [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zodpey SP. Protective effect of bacillus Calmette Guιrin (BCG) vaccine in the prevention of leprosy: a meta-analysis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:86–93. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.31891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Merle CSC, Cunha SS, Rodrigues LC. BCG vaccination and leprosy protection: review of current evidence and status of BCG in leprosy control. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2010;9:209–222. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Setia MS, Steinmaus C, Ho CS, Rutherford GW. The role of BCG in prevention of leprosy: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:162–170. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70412-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Gupte MD. South India immunoprophylaxis trial against leprosy: relevance of findings in the context of leprosy trends. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 2001;69:S10–S13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sehgal VN, Sardana K. Lepra vaccine: misinterpreted myth. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:164–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zodpey SP, Ambadekar NN, Thakur A. Effectiveness of Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG) vaccination in the prevention of leprosy: a population-based case-control study in Yavatmal District, India. Public Health. 2005;119:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Muliyil J, Nelson KE, Diamond EL. Effect of BCG on the risk of leprosy in an endemic area: a case control study. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1991;59:229–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Narang T, Kaur I, Kumar B, Radotra BD, Dogra S. Comparative evaluation of immunotherapeutic efficacy of BCG and mw vaccines in patients of borderline lepromatous and lepromatous leprosy. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 2005;73:105–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Katoch K, Katoch VM, Natrajan M, Sreevatsa, Gupta UD, Sharma VD, et al. 10-12 years follow-up of highly bacillated BL/LL leprosy patients on combined chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Vaccine. 2004;22:3649–3657. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Reveiz L, Buendía JA, Téllez D. Chemoprophylaxis in contacts of patients with leprosy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2009;26:341:9–341:9. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892009001000009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Schuring RP, Richardus JH, Pahan D, Oskam L. Protective effect of the combination BCG vaccination and rifampicin prophylaxis in leprosy prevention. Vaccine. 2009;27:7125–7128. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]