Abstract

Incontinentia pigmenti is a rare X-linked genodermatosis that affects mainly female neonates. The first manifestation occurs in the early neonatal period and progresses through four stages: vesicular, verruciform, hyperpigmented and hypopigmented. Clinical features also manifest themselves through changes in the teeth, eyes, hair, central nervous system, bone structures, skeletal musculature and immune system. The authors report the case of a patient with cutaneous lesions and histological findings that are compatible with the vesicular stage, emphasizing the importance of early diagnosis and appropriate therapeutic management.

Keywords: Genetic diseases, X-linked; Incontinentia pigmenti; Pigmentation disorders

INTRODUCTION

Incontinentia pigmenti or Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome is a rare genodermatosis, linked to X chromosome, of autosomal dominant character, which affects ectodermal and mesodermal tissues, such as skin, eyes, teeth and central nervous system.1-4 There are around 800 registered cases worldwide and the estimated incidence is about 1 to every 40.000 children.5

It is a disease of difficult diagnosis, which manifests itself during the first months of life and affects mainly female neonates, being lethal, in most cases, when it occurs in males.4 It was described for the first time by Garrod in 1903, and Sulzberger was the one who recognized the pathogenesis involved in the syndrome, in 1926.5

The authors report a case of typical clinical manifestations and histopathological findings compatible with incontinentia pigmenti in the vesicularbullous stage, emphasizing the importance of recognizing this disease due to great possibility of extracutaneous manifestations, which must be treated early to avoid sequelae.

CASE REPORT

Female patient, one month-old, with onset of small papules, vesicles and linear crusts on upper and lower limbs since birth. Prenatal and delivery occurred without complications and the child did not present comorbidities.

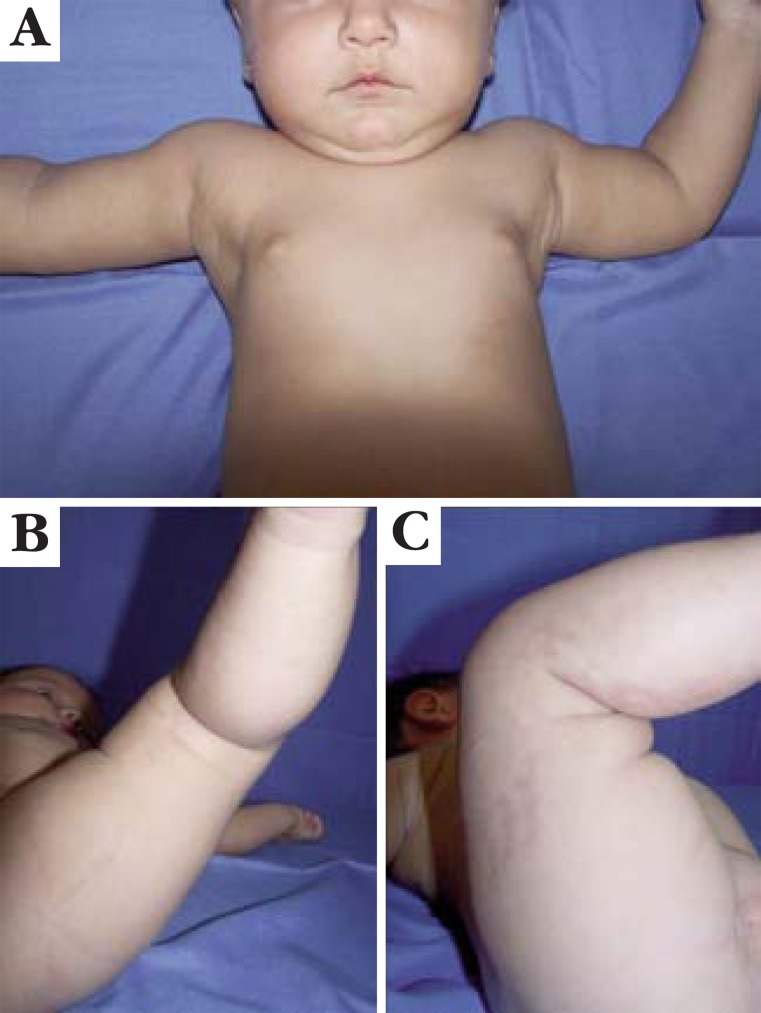

During the dermatological exam vesiculobullous injuries and crusts were found in a linear disposition along the lines of Blaschko, grouped, located on flexural surfaces of the upper limbs, lateral face of the right lower limb and posterior face of the left lower limb (Figures 1 and 2).

FIGURE 1.

A) Vesicular- Bullous linear lesions of flexural surfaces of upper limbs B) Vesicular- Bullous lesions and crusts on lateral side of lower right limb

FIGURE 2.

A) Vesicular-Bullous lesions on posterior face of lower left limb B) Lesions on lateral face of lower right limb

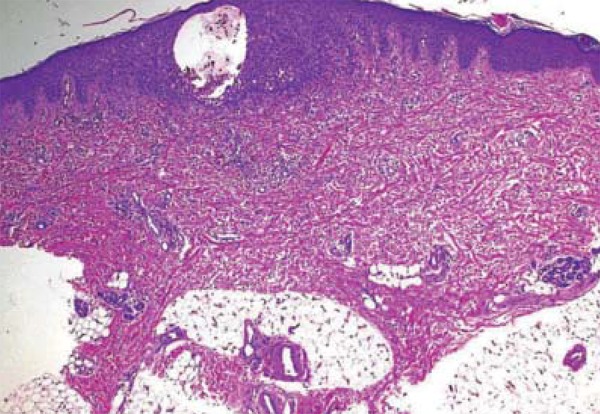

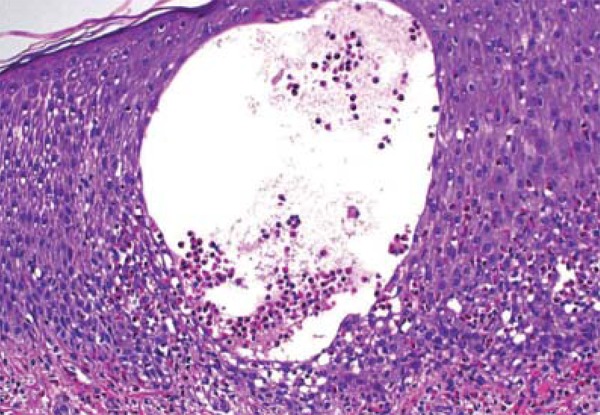

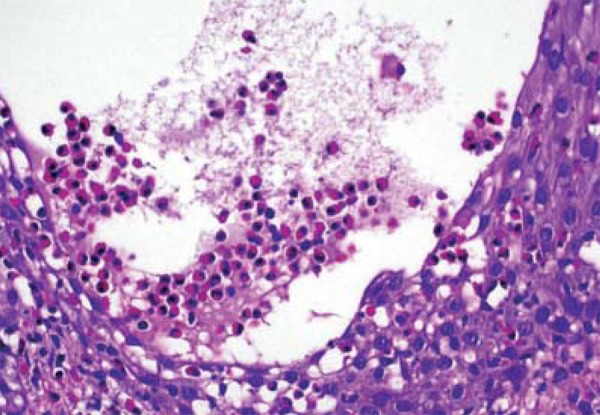

The anatomopathological exam revealed spongiosis and intraepidermal vesicles containing numerous eosinophils (Figures 3, 4 and 5). The Tzanck test identified no viral inclusions or bacterial colonies.

FIGURE 3.

Anatomopathological exam: Intraepidermal vesicles (H&E, 40x)

FIGURE 4.

Anatomopathological exam: Spongiosis and numerous eosinophils inside of the intraepidermal vesicle (H&E, 100x)

FIGURE 5.

Anatomopathological exam: In the detail, eosinophils inside of intraepidermal vesicle (H&E, 200x)

Physical exam findings and the result of complementary exams were compatible with the diagnosis of Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome in the vesicular-bullous stage. The cutaneous lesions were treated with low-potency topical corticoid and emollients; the child was referred to neurological, ophthalmological and pediatric evaluation, which were within normal standards. Relatives were oriented regarding the evolution phases of the disease and the need of multidisciplinary follow-up.

After six months there was an onset of linear hypochromic lesions on the locations previously affected by vesiculobullous lesions, corresponding to the hypopigmentation stage of Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

A) Absence of lesions on upper limbs B) Residual linear hypochromic lesions on posterior face of left lower limb C) Linear hypochromic lesions on posterior face of right lower limb

DISCUSSION

Incontinentia pigmenti is caused by a mutation on the NEMO gene, located on the q28 portion of X chromosome. It affects the skin and several systemic organs with variable clinical expression.6

The first manifestations occur in the neonatal period and progress through several well-defined steps, possibly occurring concomitantly or sequentially. The first stage is named vesicular or vesicular-bullous, characterized by vesicles and linear inflammatory bubbles that appear at birth or during the first two months and can last from weeks to months. The second stage is the verrucous, when linear verrucous hyperkeratotic plaques appear with variable duration. Next the hyperpigmentation stage occurs, with the onset of brown or bluish-gray pigmentation, distributed in Blaschko lines, starting in infancy and slowly fading until it disappears in adulthood. The last stage is the hypopigmentation, when linear hypopigmented macules appear, with absence of cutaneous appendixes on trunk and limbs during adult age.4,7

In the case reported, there was the predominance of vesiculobullous lesions, which allowed the clinical picture classification as vesicular-bullous stage. However, some lesions presented with a verrucous aspect and the onset of crusts, suggesting the start of the second stage of the disease, corresponding to the verrucous stage.

In up to 80% of the cases of incontinentia pigmenti there are associated extracutaneous manifestations.2,4,5 The following structures may be affected: teeth, manifesting as anodontia, delayed dentition and malformed teeth; retinal and corneal, microphthalmia, cataract, iris hypoplasia, uveitis, nystagmus, strabismus and myopia changes indicate ocular involvement; baldness may represent hair involvement; central nervous system involvement may have variable clinical presentation with convulsions, seizures, mental retardation, ischemic strokes, hydrocephalus and anatomical abnormalities; bone structures and skeletal musculature may have their development compromised and the child evolves with syndactyly, cranial deformities, dwarfism, supernumerary ribs, hemiatrophy and shortening the legs and arms. 8,9 There may be immunological changes due to defective neutrophil chemotaxis and lymphocyte function. Since it is a genodermatosis, there is also the possibility of association with malignancies, such as hematological neoplasms, Wilms' tumor and retinoblastoma.2,4,5

The patient in question underwent multidisciplinary evaluation by a team composed of pediatricians, neurologists and ophthalmologists and up to now no extracutaneous manifestation was identified. It is known, however, that extracutaneous involvement may appear late, which justifies the continuous follow-up of these patients even after the vesicularbullous lesions have disappeared.

Histopathology varies according to the evolutionary stage of the disease. In the first stages it shows an increase of eosinophils and formation of intraepidermal vesicules. In the verrucous phase hyperkeratosis, dyskeratosis, acanthosis and papillomatosis can be identified. Later, melanine deposits on the dermis with melanophages are found in the hyperpigmentation stage. Finally, in the hypopigmentation stage discreet epidermal atrophy and absence of annexes may be seen.4,10

Histopathological findings associated with physical characteristics are enough to define the diagnosis. Recently diagnostic criteria were proposed for the syndrome, the major criterium being the typical cutaneous alterations of one of the evolutionary phases of the disease. The minor criteria correspond to dental, ocular, neurological, osseous and immunological alterations, as well as compatible anatomopathological exam. Genetic alteration and presence of family members also affected by the disease should also be taken into consideration.10

The cutaneous manifestations do not need specific treatment; spontaneous resolution of lesions occurs normally. Emollients and topical corticoids can be used in the first stages of the disease. Secondary bacterial infections may occur and must be treated with antibiotics. The management of extracutaneous manifestations must be done by a multidisciplinary team and varies according to the affected organ. Furthermore, genetic counseling is also important since the disorder is of autosomal dominant transmission.1,2,4,5

Therefore, in spite of the rarity of this pathology, one must be alert for early diagnosis, recognizing the typical cutaneous manifestations of each evolutionary phase of the disease, for adequate genetic counseling and better management of extracutaneous manifestations when these are present.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests: none

Financial Support: none

Work performed at Instituto Lauro de Souza Lima (ILSL) - Bauru (SP), Brazil.

How to cite this article: Borges J, Cuzzi T, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA, Manela-Azulay M. Incontinentia pigmenti or Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome: a rare X-linked genodermatosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(3):486-9.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mühlenstädt E, Eigelshoven S, Hoff NP, Reifenberger J, Homey B, Bruch-Gerharz D. Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome. Hautarzt. 2010;61:831–833. doi: 10.1007/s00105-010-2046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ehrenreich M, Tarlow MM, Godlewska-Janusz E, Schwartz RA. Incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome): a systemic disorder. Cutis. 2007;79:355–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motamedi MH, Lotfi A, Azizi T, Moshref M, Farhadi S. Incontinentia pigmenti. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:302–304. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.64291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pereira MAC, Mesquita LAF, Budel AR, Cabral CSP, Feltrim AS. X-linked incontinentia pigmenti or Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome: a case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:372–375. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962010000300013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buinauskiene J, Buinauskaite E, Valiukeviciene S. Incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome) in neonates. Medicina (Kaunas) 2005;41:496–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee Y, Kim S, Kim K, Chang M. Incontinentia pigmenti in a newborn with NEMO mutation. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26:308–311. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.2.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llano-Rivas I, Soler-Sánchez T, Málaga-Diéguez I, Fernández-Toral J. Incontinentia pigmenti. Four patients with different clinical manifestations. An Pediatr (Barc) 2012;76:156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.anpedi.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minic S, Trpinac D, Gabriel H, Gencik M, Obradovic M. Dental and oral anomalies in incontinentia pigmenti: a systematic review. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0721-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minic S, Trpinac D, Obradovic M. Systematic review of central nervous system anomalies in incontinentia pigmenti. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:25–25. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minić S, Trpinac D, Obradović M. Incontinentia pigmenti: diagnostic criteria update. Clin Genet. 2013 Jun 26; doi: 10.1111/cge.12223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]