Abstract

Importance

The 50th anniversary of the first Surgeon General’s Report on smoking and health is celebrated in 2014. This seminal document inspired efforts by government s, non-governmental organizations, and the private sector to reduce the toll of cigarette smoking through reduced initiation and increased cessation.

Objective

To quantify reductions in smoking -related mortality associated with implementation of tobacco control since 1964.

Design, Setting and Participants

Smoking histories for individual birth cohorts that actually occurred and under likely scenarios had tobacco control never emerged were estimated. National mortality rates and mortality rate ratio estimates from analytical studies of the effect of smoking on mortality yielded death rates by smoking status. Actual smoking -related mortality from 1964–2012 was compared to estimated mortality under no tobacco control that included a likely scenario (primary counterfactual) and upper and lower bounds that would capture plausible alternatives.

Exposure

National Health Interview Surveys yielded cigarette smoking histories for the US adult population from 1964–2012.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Number of premature deaths avoided and years of life saved were primary outcomes. Change in life expectancy at age 40 associated with change in cigarette smoking exposure constituted another measure of overall health outcomes.

Results

From 1964–2012, an estimated 17.6 million deaths were related to smoking, an estimated 8.0 (7.4–8.3, for the lower and upper tobacco control counterfactuals, respectively) million fewer premature smoking-induced deaths than what would have occurred under the alternatives and thus associated with tobacco control (5.3 (4.8–5.5) million males and 2.7 (2.5–2.7) million females). This resulted in an estimated 157 (139–165) million years of life saved, a mean of 19.6 years for each beneficiary, (111 (97–117) million for males, 46 (42–48) million for females). During this time, estimated life expectancy at age 40 increased 7.8 years for males and 5.4 years for females, of which tobacco control is associated with2.3 (1.8–2.5) years [30% (23–32%)] of the increase for males and 1.6 (1.4–1.7) years [29% (25–32%)] for females.

Conclusions and Relevance

Tobacco control is associated with avoidance of millions of premature deaths, and an estimated extended mean lifespan of 19–20 years. While tobacco control represents an important public health achievement, smoking continues to be the leading contributor to the nation’s death toll.

Keywords: Smoking, Mortality, Tobacco control, Surgeon General’s Report

January 2014 marks the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the first Surgeon General’s report on smoking and health.1 The report inaugurated new multi-pronged efforts to reduce cigarette smoking and its toll. Those efforts by governments, voluntary organizations, and the private sector – education on smoking’s dangers, increases in cigarette taxes, smoke-free air laws, media campaigns, marketing and sales restrictions, lawsuits, and cessation treatment programs – have comprised the nation’s tobacco control efforts. Recently, Warner et al.2 documented an important reduction in cigarette consumption associated with tobacco control. This report estimates how many Americans have gained additional years of life from 1964 through 2012 as a result of tobacco control-influenced decisions to quit smoking or to never start.

The Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) estimated 800,000 lung cancer deaths avoided between 1975 and 2000 as a result of tobacco control.3 CISNET used a common set of smoking history and mortality parameters in population cancer models to estimate the expected difference in the number of lung cancer deaths between smoking rates under actual tobacco control and under no tobacco control, i.e., if smoking behavior subsequent to 1964 had not been affected by tobacco control.4,5 These results were extended to consider all deaths rather than just lung cancer deaths and expand the examined time period from 1975–2000 to 1964–2012 to estimate the number of early deaths avoided and life-years saved that were associated with reduced cigarette smoking during this period. The relationship between tobacco control and life expectancy was also estimated.

METHODS

Smoking histories prior to 1964 were used to estimate likely patterns of smoking in the absence of tobacco control, which are referred to as counterfactual scenarios. In conjunction with national mortality rates and epidemiological studies of smoking and mortality, death rates expected under these counterfactuals were estimated. The differences in premature deaths, and associated life-years gained, under observed smoking rates and those under counterfactual scenarios were used to estimate the benefits associated with tobacco control.

Smoking history estimation

Holford et al.6 refined the Anderson et al.7 technique, using National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS) for 1965–2009 to estimate smoking prevalence, initiation and cessation for birth cohorts born after 1864. Thirty-three surveys provided smoking status, 13 of which also provided age at initiation, cessation, and intensity, thereby enabling retrospective construction of smoking histories. Higher mortality among smokers implies that survey participants represent a biased sample of the population born in a given year. The method corrects for this bias,6 providing ever-smoker (individuals who have smoked 100 or more cigarettes) prevalence for ages 0–99 and birth cohorts from 1864–1980 by one-year intervals. Conditional cessation probabilities were similarly obtained, yielding cumulative estimates of cessation. Multiplying the cumulative cessation probability by ever-smoker prevalence provided former smoker prevalence, and multiplying by the complement yielded current -smoker prevalence. Never-smoker prevalence is one minus ever-smoker prevalence. These estimates reflect smoking patterns under actual tobacco control since 1964.

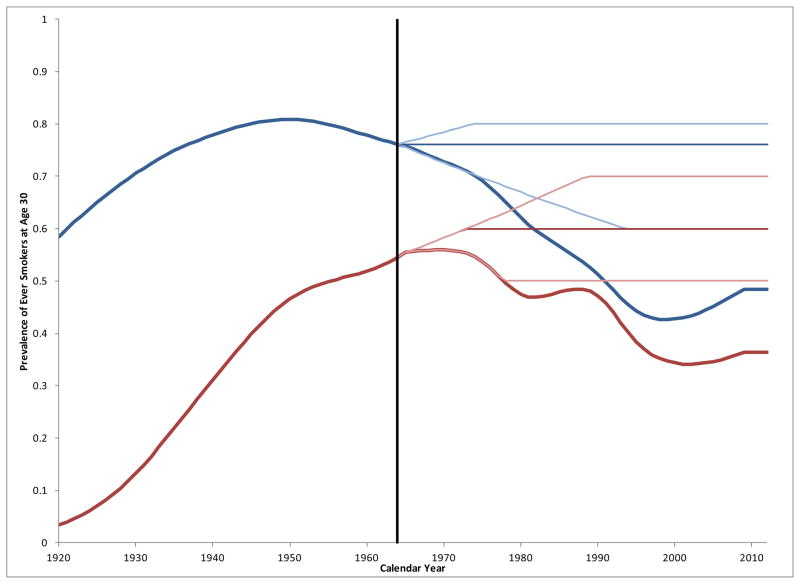

For the no tobacco control counterfactuals, Holford and Clarke’s method4 was modified to estimate smoking prevalence, initiation, and cessation rates that could be expected had the era of tobacco control following the 1964 Surgeon General’s Report1 (SGR) not occurred. Ever-smoker prevalence by cohort was considered to develop a plausible range of counterfactuals. Most all initiation has generally taken place by age 30, so this provides a useful reference for positing alternative initiation scenarios. Figure 1 shows ever -smoker prevalence estimates at age 30 by year and sex.6

Figure 1.

Estimated ever-smoker prevalence at age 306 by gender (male=blue, female=red) [actual (heavy), counterfactuals (light)].

Male smoking prevalence began to decline before 1964, possibly reflecting awareness of research from the early 1950s showing an association with lung cancer.8,9 The 1920 birth cohort achieved the male maximum ever-smoking prevalence of about 80 percent at age 30, and a return to this was defined as the upper no tobacco control counterfactual for males. The actual level in 1964 was the primary counterfactual, and a decline to60% was defined as the lower bound.

Increasing social acceptance of smoking and advertising targeting women tended to increase smoking prevalence in females just when awareness of adverse health effects was taking hold. The rate of smoking among females was increasing at a rate that paralleled that of males about three decades earlier.10 As an upper bound counterfactual, female ever-smoker prevalence at 30 was assumed to have continued its upward trajectory, eventually reaching70%, 10 percentage points below the maximum for males. Amore conservative increase to 60% prevalence was defined as the primary counterfactual, and decline to 50% was defined as the lower limit, despite clear indications that this would have been unlikely.

All-cause mortality rates by birth-cohort and smoking status

Rosenberg et al developed methodology for estimating cause -specific cohort life tables by smoking status.11 As described in the supplementary material, the method was adapted to obtain all-cause cohort life tables by gender and smoking status (never, former and current) for the 1864–1980 birth cohorts. The methodology uses (1) mortality relative risk estimates by gender and smoking status derived from the first two American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Studies12,13 and the NHANES Epidemiologic Follow-up Studies14 and (2) smoking prevalence described above to partition US all-cause mortality tables15 by smoking status.

Population estimates

US population estimates by single years of age (0–85+) were obtained from US government websites: 1964–1968—US Census,16 1969–2011—Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results,17 and 2012 —US Census.18

Calculation of premature deaths

The difference between mortality rates for both current or former smokers and never-smokers measures the avoidable increase related to cigarette smoking exposure. The number of premature deaths is the product of this difference and the corresponding number of current or former smokers (population × smoking prevalence). These were calculated by single year of age, calendar year, smoking status, and gender, and summed over the appropriate age range for each year yielding total premature deaths. These were calculated for all ages and for those <65 years old. The difference under the actual and no tobacco control scenarios provided a measure of mortality reduction related to tobacco control.

Years of Life Lost

Yearly death rates for a cohort were used to estimate expected years of life remaining given that an individual is alive at a given age (see supplementary material). All deaths were assumed to occur before age 100, the upper limit of reported age-specific death rates. If a rate was not available for a particular age, the value from the nearest cohort was used. Expected years of life remaining estimates years of life lost (YLL) for a premature death. Total YLL is the sum of the product of number of premature deaths and expected years of life remaining for a never-smoker. Total YLL before age 65 was calculated to examine this outcome of smoking associated mortality on the working-age population.

Life expectancy

Life expectancy provides an alternative summary measure of mortality rates, and it is commonly used to assess the overall health of a population. It essentially envisions a hypothetical population that experiences a set of age-specific mortality rates that occur in a year, and determines the resulting expected length of life after a given age. This was calculated using actual and counterfactual mortality rates beginning at age 40 to better measure the effect of cigarette smoking and to remove infant and childhood mortality effects. Life expectancy at ages 50 and 60 are reported in the supplementary material (Figure A9).

RESULTS

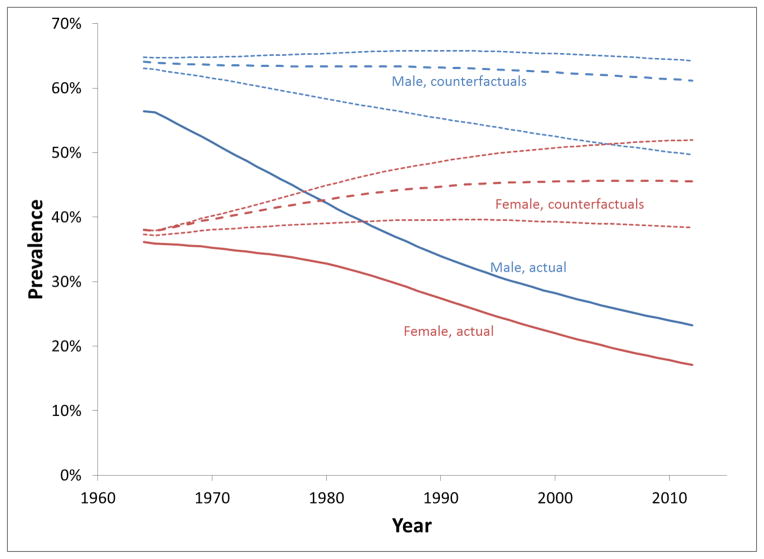

Figure 2 shows prevalence of current-smokers, ages 18 and older, under the actual and counterfactual scenarios. For males, the actual trend was steadily downward, and while the decrease for females was initially slow, it accelerated after1980. For the lower male counterfactual, prevalence declined steadily, while the upper and primary estimates were fairly flat initially, but declined slightly after 1990. For females, there was a modest increase for the lower counterfactual and greater increases for primary and higher scenarios. By 2012, under the counterfactual scenarios, smoking prevalence would have ranged from 50% to 64% for males and from 38% to 52% for females. Age-specific prevalences are shown in the supplementary material (Figures A1–A3).

Figure 2.

Estimated prevalence of current smokers: actual (solid), primary counterfactual (dashed) and bounds (dotted).

Table 1 shows estimated number of premature deaths related to smoking in the US from 1964–2012 compared to number of deaths estimated under the counterfactual scenarios. With tobacco control, the model estimates a total of 17.7 million smoking-attributable deaths between 1964 and 2012. Overall, a reduction of 8.0 (7.4–8.3) million premature smoking-attributable deaths (subsequently referred to as “lives saved”) were associated with tobacco control from 1964–2012 (5.3 (4.8–5.5) million males and 2.7 (2.5–2.7) million females). More than half of these, 4.4 (3.8–4.6) million, occurred before age65 (3.4 (2.9–3.6) million males and 1.0 (0.9–1.1) million females). The number of lives saved each year has increased steadily over time. So too has the percent saved as a fraction of smoking-attributable deaths that are projected (applying the counterfactuals to both men and women) to have occurred in the absence of tobacco control, from 11%in the first decade to 48% (44–49%) in 2004–2012. For deaths before age 65, the estimated percent of lives saved increased from 15% to 64% (59%–66%). In recent years, the proportion of lives saved among women [69% (64%–72%)] appear to be even greater than among men [63% (57%–64%)].

Table 1.

Estimated smoking attributable deaths (x1000) avoided by tobacco control (all ages and ages <65).

| Actual | Stable | Decrease | Increase | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| No. | Saved | % | No. | Saved | % | No. | Saved | % | ||

| All ages | ||||||||||

| Males | ||||||||||

| 1964–1973 | 2,512 | 2,867 | 355 | 12% | 2,867 | 355 | 12% | 2,867 | 355 | 12% |

| 1974–1983 | 2,711 | 3,377 | 665 | 20% | 3,374 | 663 | 20% | 3,380 | 668 | 20% |

| 1984–1993 | 2,903 | 3,930 | 1,027 | 26% | 3,897 | 994 | 25% | 3,953 | 1,050 | 27% |

| 1994–2003 | 2,744 | 4,257 | 1,514 | 36% | 4,119 | 1,375 | 33% | 4,328 | 1,584 | 37% |

| 2004–2012 | 2,271 | 4,028 | 1,758 | 44% | 3,729 | 1,458 | 39% | 4,150 | 1,879 | 45% |

| Total | 13,141 | 18,460 | 5,319 | 29% | 17,986 | 4,845 | 27% | 18,678 | 5,537 | 30% |

| Females | ||||||||||

| 1964–1973 | 497 | 526 | 29 | 5% | 526 | 29 | 5% | 526 | 29 | 5% |

| 1974–1983 | 834 | 980 | 146 | 15% | 979 | 146 | 15% | 980 | 146 | 15% |

| 1984–1993 | 1,148 | 1,590 | 442 | 28% | 1,584 | 436 | 28% | 1,591 | 442 | 28% |

| 1994–2003 | 1,155 | 2,064 | 909 | 44% | 2,028 | 873 | 43% | 2,074 | 918 | 44% |

| 2004–2012 | 895 | 2,050 | 1,155 | 56% | 1,935 | 1,040 | 54% | 2,101 | 1,206 | 57% |

| Total | 4,529 | 7,210 | 2,681 | 37% | 7,053 | 2,524 | 36% | 7,271 | 2,742 | 38% |

| Both | ||||||||||

| 1964–1973 | 3,009 | 3,393 | 384 | 11% | 3,393 | 384 | 11% | 3,393 | 384 | 11% |

| 1974–1983 | 3,545 | 4,357 | 811 | 19% | 4,353 | 808 | 19% | 4,359 | 814 | 19% |

| 1984–1993 | 4,052 | 5,520 | 1,469 | 27% | 5,481 | 1,430 | 26% | 5,544 | 1,492 | 27% |

| 1994–2003 | 3,899 | 6,322 | 2,423 | 38% | 6,147 | 2,248 | 37% | 6,402 | 2,503 | 39% |

| 2004–2012 | 3,166 | 6,079 | 2,913 | 48% | 5,664 | 2,498 | 44% | 6,251 | 3,086 | 49% |

| Total | 17,670 | 25,670 | 8,000 | 31% | 25,039 | 7,368 | 29% | 25,950 | 8,279 | 32% |

| Ages <65 | ||||||||||

| Males | ||||||||||

| 1964–1973 | 1,335 | 1,593 | 258 | 16% | 1,593 | 258 | 16% | 1,593 | 258 | 16% |

| 1974–1983 | 1,214 | 1,615 | 400 | 25% | 1,612 | 398 | 25% | 1,618 | 403 | 25% |

| 1984–1993 | 1,041 | 1,613 | 572 | 35% | 1,580 | 539 | 34% | 1,636 | 595 | 36% |

| 1994–2003 | 835 | 1,773 | 938 | 53% | 1,636 | 801 | 49% | 1,842 | 1,007 | 55% |

| 2004–2012 | 738 | 1,975 | 1,236 | 63% | 1,708 | 970 | 57% | 2,069 | 1,331 | 64% |

| Total | 5,164 | 8,569 | 3,405 | 40% | 8,129 | 2,965 | 36% | 8,758 | 3,594 | 41% |

| Females | ||||||||||

| 1964–1973 | 284 | 306 | 22 | 7% | 306 | 22 | 7% | 306 | 22 | 7% |

| 1974–1983 | 366 | 443 | 78 | 18% | 443 | 77 | 17% | 443 | 78 | 18% |

| 1984–1993 | 347 | 504 | 156 | 31% | 498 | 151 | 30% | 504 | 157 | 31% |

| 1994–2003 | 248 | 548 | 300 | 55% | 513 | 264 | 52% | 558 | 309 | 55% |

| 2004–2012 | 198 | 649 | 451 | 69% | 555 | 357 | 64% | 699 | 500 | 72% |

| Total | 1,443 | 2,450 | 1,007 | 41% | 2,315 | 871 | 38% | 2,510 | 1,067 | 42% |

| Both | ||||||||||

| 1964–1973 | 1,619 | 1,900 | 281 | 15% | 1,900 | 281 | 15% | 1,900 | 281 | 15% |

| 1974–1983 | 1,580 | 2,058 | 478 | 23% | 2,055 | 475 | 23% | 2,061 | 481 | 23% |

| 1984–1993 | 1,389 | 2,117 | 728 | 34% | 2,078 | 689 | 33% | 2,141 | 752 | 35% |

| 1994–2003 | 1,083 | 2,321 | 1,238 | 53% | 2,149 | 1,065 | 50% | 2,400 | 1,316 | 55% |

| 2004–2012 | 936 | 2,624 | 1,687 | 64% | 2,263 | 1,327 | 59% | 2,768 | 1,831 | 66% |

| Total | 6,607 | 11,019 | 4,412 | 40% | 10,444 | 3,837 | 37% | 11,268 | 4,661 | 41% |

Table 2 shows estimated YLL and estimated lives saved under the counterfactual scenarios by calendar year and gender for all ages and ages less than 65. Overall, a gain of 157 (139–165) million years of life was associated with tobacco control, 111 (98–117) million for males and 46 (42–48) million for females. This suggests that individuals who avoided a premature smoking-related death gained 19.6 years of life on average (157 million years divided by 8.0 million lives saved). Before age 65, 42 (35–44) million years of life were saved, 34 (29–36) million for males and 8 (6–8) million for females. Similar to the pattern for premature deaths, the trend in proportion of years of life saved has shown a steady increase over time, increasing to 69% (63–71%) in 2004–2012 from 15%in 1964–1973. The proportion of years of life saved has been greater among women than men.

Table 2.

Years of life lost (x1000) by tobacco control and gender (all ages and ages <65).

| Actual | Stable | Decrease | Increase | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| No. | Saved | % | No. | Saved | % | No. | Saved | % | ||

| All ages | ||||||||||

| Males | ||||||||||

| 1964–1973 | 40,585 | 47,579 | 6,994 | 15% | 47,579 | 6,994 | 15% | 47,579 | 6,994 | 15% |

| 1974–1983 | 40,625 | 52,565 | 11,939 | 23% | 52,466 | 11,841 | 23% | 52,661 | 12,035 | 23% |

| 1984–1993 | 40,640 | 59,639 | 18,999 | 32% | 58,535 | 17,895 | 31% | 60,375 | 19,735 | 33% |

| 1994–2003 | 37,446 | 69,866 | 32,419 | 46% | 65,676 | 28,230 | 43% | 71,838 | 34,392 | 48% |

| 2004–2012 | 32,287 | 73,132 | 40,845 | 56% | 65,013 | 32,725 | 50% | 76,085 | 43,797 | 58% |

| Total | 191,584 | 302,781 | 111,197 | 37% | 289,269 | 97,685 | 34% | 308,537 | 116,953 | 38% |

| Females | ||||||||||

| 1964–1973 | 8,970 | 9,609 | 640 | 7% | 9,609 | 640 | 7% | 9,609 | 640 | 7% |

| 1974–1983 | 13,591 | 16,305 | 2,715 | 17% | 16,293 | 2,702 | 17% | 16,305 | 2,715 | 17% |

| 1984–1993 | 16,852 | 24,166 | 7,314 | 30% | 23,964 | 7,112 | 30% | 24,191 | 7,339 | 30% |

| 1994–2003 | 15,266 | 30,193 | 14,927 | 49% | 29,133 | 13,867 | 48% | 30,496 | 15,230 | 50% |

| 2004–2012 | 11,717 | 32,103 | 20,386 | 64% | 29,166 | 17,449 | 60% | 33,585 | 21,868 | 65% |

| Total | 66,396 | 112,377 | 45,981 | 41% | 108,164 | 41,769 | 39% | 114,187 | 47,791 | 42% |

| Both | ||||||||||

| 1964–1973 | 49,555 | 57,188 | 7,633 | 13% | 57,188 | 7,633 | 13% | 57,188 | 7,633 | 13% |

| 1974–1983 | 54,216 | 68,870 | 14,654 | 21% | 68,759 | 14,543 | 21% | 68,966 | 14,750 | 21% |

| 1984–1993 | 57,493 | 83,805 | 26,313 | 31% | 82,499 | 25,007 | 30% | 84,566 | 27,073 | 32% |

| 1994–2003 | 52,712 | 100,059 | 47,347 | 47% | 94,809 | 42,096 | 44% | 102,334 | 49,622 | 48% |

| 2004–2012 | 44,004 | 105,235 | 61,231 | 58% | 94,178 | 50,174 | 53% | 109,670 | 65,666 | 60% |

| Total | 257,980 | 415,157 | 157,178 | 38% | 397,433 | 139,454 | 35% | 422,724 | 164,744 | 39% |

| Ages <65 | ||||||||||

| Males | ||||||||||

| 1964–1973 | 12,095 | 14,589 | 2,494 | 17% | 14,589 | 2,494 | 17% | 14,589 | 2,494 | 17% |

| 1974–1983 | 9,876 | 13,391 | 3,515 | 26% | 13,333 | 3,457 | 26% | 13,447 | 3,572 | 27% |

| 1984–1993 | 8,343 | 13,733 | 5,390 | 39% | 13,146 | 4,802 | 37% | 14,115 | 5,772 | 41% |

| 1994–2003 | 7,007 | 17,282 | 10,275 | 59% | 15,386 | 8,379 | 54% | 18,089 | 11,082 | 61% |

| 2004–2012 | 5,792 | 18,232 | 12,440 | 68% | 15,272 | 9,480 | 62% | 19,124 | 13,332 | 70% |

| Total | 43,113 | 77,227 | 34,114 | 44% | 71,726 | 28,613 | 40% | 79,364 | 36,251 | 46% |

| Females | ||||||||||

| 1964–1973 | 2,751 | 2,973 | 222 | 7% | 2,973 | 222 | 7% | 2,973 | 222 | 7% |

| 1974–1983 | 2,827 | 3,427 | 600 | 17% | 3,420 | 593 | 17% | 3,427 | 600 | 17% |

| 1984–1993 | 2,270 | 3,429 | 1,159 | 34% | 3,332 | 1,062 | 32% | 3,442 | 1,172 | 34% |

| 1994–2003 | 1,359 | 3,694 | 2,336 | 63% | 3,319 | 1,961 | 59% | 3,819 | 2,460 | 64% |

| 2004–2012 | 1,115 | 4,314 | 3,199 | 74% | 3,627 | 2,512 | 69% | 4,783 | 3,668 | 77% |

| Total | 10,323 | 17,838 | 7,515 | 42% | 16,672 | 6,349 | 38% | 18,444 | 8,121 | 44% |

| Both | ||||||||||

| 1964–1973 | 14,847 | 17,563 | 2,716 | 15% | 17,563 | 2,716 | 15% | 17,563 | 2,716 | 15% |

| 1974–1983 | 12,703 | 16,818 | 4,114 | 24% | 16,753 | 4,050 | 24% | 16,874 | 4,171 | 25% |

| 1984–1993 | 10,613 | 17,162 | 6,549 | 38% | 16,478 | 5,864 | 36% | 17,557 | 6,943 | 40% |

| 1994–2003 | 8,366 | 20,976 | 12,611 | 60% | 18,705 | 10,339 | 55% | 21,908 | 13,542 | 62% |

| 2004–2012 | 6,907 | 22,546 | 15,639 | 69% | 18,900 | 11,993 | 63% | 23,907 | 17,000 | 71% |

| Total | 53,436 | 95,065 | 41,629 | 44% | 88,398 | 34,962 | 40% | 97,808 | 44,372 | 45% |

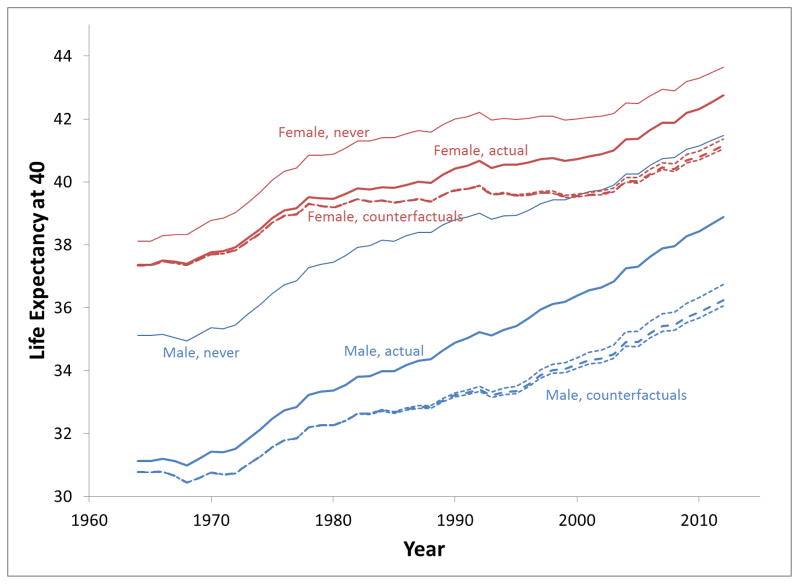

Changing from the perspective of individuals who avoided premature deaths to the population as a whole, the estimated trend in life expectancy at age 40is shown in Figure 3. For males, life expectancy at age 40 increased 7.8 years (31.1 in 1964 to 38.9 in 2012). Without tobacco control the estimated increase would have been 5.5 years (5.3–6.0). Hence, 2.3 (1.8–2.5) years or30 % (23–32%) of improved life expectancy for males is projected to be associated with tobacco control. In females, life expectancy at age 40 increased 5.4 years (37.4 to 42.7), but without tobacco control it would have been projected to increase by only 3.8 years (37.3 to 41.2). Tobacco control appears to be associated with 1.6 (1.4–1.7) years of the improvement in life expectancy for females or 29% (25–32%) of the gain. The supplementary materials show estimates of life expectancy at ages 50 and 60 (Figure A9).

Figure 3.

Life expectancy at age 40: actual (heavy), primary counterfactuals (dashed), bounds (dotted), and never-smokers (light).

DISCUSSION

Tobacco control has made a unique and substantial contribution to public health over the past half century. This study provides a quantitative perspective to the magnitude of that contribution. The collectivity of tobacco control efforts since the first Surgeon General’s report was associated with the avoidance of 8.0 (7.4–8.3) million premature smoking-attributable deaths. Furthermore, with 157 million life years saved, the beneficiaries of these avoided early deaths have gained, on average, nearly two decades of life.

In previous work, Warner concluded that 789,000 premature deaths had been avoided through 1985.19 He estimated that tobacco control -influenced decisions not to smoke through that year would have resulted in 2.1 million additional premature deaths avoided between 1986 and 2000. Estimates from this study are substantially higher than those reported by Warner because this study evaluated a much longer period of time, and the gap between actual smoking and the counterfactual scenarios has changed substantially.

Of the 8.0 million premature smoking deaths, 4.4 (3.8–4.6) million were estimated to occur before age 65. This implies the avoidance of a large productivity loss due to illness and death during those working ages, estimated to impose a cost of about $100 billion annually in the US.20

The relationship between tobacco control and life expectancy was also estimated: an increase of 2.3 (1.8–2.5) years for males and1.6 (1.4–1.7) years for females after age 40. That these figures represent 30% (23–32%) for males and 29% (25–31%) for females of the total life expectancy gain from 1964–2012 demonstrates the important influence of tobacco control on the life expectancy of US adults.

LIMITATIONS

The specifics of the findings of this study depend on a number of assumptions, as well as the methods by which they were incorporated in the analysis. Most importantly, the findings depend on counterfactual estimates of what smoking prevalence would have been in the absence of tobacco control. A cohort analysis was employed, which considered a range of estimates based on smoking histories prior to 1964. Use of smoking prevalence at age 30, when further initiation is unlikely, provided a group whose initiation of smoking would not have been influenced by the Surgeon General’s Report in 1964.

It is much more difficult to isolate the effect on cessation probabilities of what transpired after 1964 from what began in the 1950s. The 1890 birth cohort provides the best estimate of cessation probabilities in the absence of tobacco control, a group in their 60s in 1950 when the first prominent research on smoking and lung cancer appeared. 8,9 The difference in males between actual smoking prevalence and the counterfactuals in 1964 (Figure 2) reflects small decreases in male smoking prevalence during the 1950sin response to those studies, publicity about which itself constituted a form of tobacco control. Somewhat artificially, examination of premature deaths avoided began in 1964, thus ignoring initial stages of tobacco control from the 1950s, because the SGR is considered to have ushered in the tobacco control era. While per capita cigarette consumption declined briefly following publication of the early research, the trend was not sustained, and it resumed its upward trajectory in 1955, continuing through 1963.2 Premature death estimates included males who benefitted from cessation in the 1950s; but their contribution to mortality was small before the 1964 milestone. However, prolonged reduction in male smoking was considered in the lower bound counterfactual scenario, which declines continuously as seen in Figure 2.

While it is conceivable that female smoking rates might have declined after 1964 in the absence of tobacco control, there is considerable evidence to suggest that these smoking rates would have continued upward.2,10 In exploring how high smoking rates would have increased, alternatives of 50%ever -smoker prevalence at age 30as the primary counterfactual and a peak of 60% the upper bound, well below the rate attained by males were considered. Males reached their maximum before 1964, but the level in 1964 was chosen as the primary counterfactual with bounds that decline to 60%or return to 80% ever-prevalence at age 30. In addition, there is uncertainty in the estimates of relative risk used in computing the mortality rates and in the actual smoking rates derived from NHIS, although these are large surveys with precise estimates.

Mortality relative risks associated with smoking are based on CPS-I and CPS-II, which cover the period of 1961–1999. Subsequent relative risks were assumed to have remained constant at the 1999 level. However, a recent study by Thun et al. 21 indicated that mortality relative risk for current compared to never-smokers may be continuing to increase, suggesting that lives saved may have been underestimated in this analysis. Another potential limitation of this analysis is that the cessation probability estimates did not control for smoking duration and years smoked. The increasing mean duration and years quit by age were indirectly accounted for in the actual control scenario by using age- and smoking-status specific mortality rates calibrated to US mortality. The expected longer mean duration for smokers and shorter years quit for former smokers under counterfactuals would not have been captured entirely, however, thereby under estimating death rates and hence health benefits from tobacco control. Further, the role of smoking intensity was not explicitly considered in this analysis, which has been declining steadily since the 1960s.6 Since intensity is likely to have been higher in the absence of tobacco control, there may have been further gains not accounted for in the analysis.

While all of these considerations could affect the findings, the estimates of life expectancy at age 40, for both 1964 and 2012 and for both genders, are close to US federal government statistics.22,23 Since the life expectancy estimates derive from the analysis, this provides strong validation of the methods and calculations.

For the future, a potential factor that may offset the gains estimated in this study is the recent increase in use, particularly among young adults, of non -cigarette forms of tobacco, such as smokeless tobacco, cigars, hookahs and e-cigarettes.24–26 If used instead of cigarettes, the health effects from these products is considerably less than that of cigarettes. However, if used in combination with cigarettes, these products may offset some of the potential benefits, especially as these young adults reach ages when smoking begins to claim its toll. The pattern of alternative tobacco product use that would have evolved had tobacco control never affected cigarette smoking is unknown.

Past successes of tobacco control have relied primarily on tax increases, media campaigns, smoke-free air laws and advertising bans. Cessation treatment policies have also played a role, but could play an increasing one. Physician interventions, such as the 5As27 and the Ask, Advise, and Connect (AAC)28 method, which encourage quitting and the use of effective cessation treatments, can increase quit rates.29 In addition, supply side policies can play an important role with the Food and Drug Administration’s recently granted authority to regulate cigarettes and smokeless tobacco products.

CONCLUSION

Despite the success of tobacco control efforts in reducing premature deaths in the US, smoking remains a glass-half-full, glass-half-empty story. During the time that tobacco control was associated with extending the lives of 8 million Americans, smoking-attributable mortality occurred in approximately 17.6 million others. Today, a half century after the Surgeon General’s first pronouncement on the toll that smoking exacts from US society, nearly a fifth of adult Americans continue to smoke, and smoking continues to claim hundreds of thousands of lives annually. No other behavior comes close to contributing so heavily to the nation’s mortality burden. Tobacco control has been a great public health success story, but it is an unfinished one and requires continued efforts to eliminate tobacco-related morbidity and mortality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in part by the National Cancer Institute (R01-CA-152956).

Footnotes

Dr. Holford had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study: collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Surgeon General’s Advisory Committee on Smoking and Health. Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service. 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warner KE, Sexton D, Gillespie DB, Levy DT, Chaloupka FJ. The impact of tobacco control on adult per capita cigarette consumption in the United States. Americal Journal of Public Health. 2013 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moolgavkar SH, Holford TR, Levy DT, et al. Impact of the reduction in tobacco smoking on lung cancer mortality in the U.S. during the period 1975–2000. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2012;104:541–548. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holford TR, Clarke LD. Development of the counterfactual smoking histories used to assess the effects of tobacco control. Risk Analysis. 2012;32:S39–S50. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01759.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeon J, Meza R, Krapcho M, Clarke LD, Byrne J, Levy DT. Actual and counterfactual smoking prevalence rates in the U.S. population via microsimulation. Risk Analysis. 2012;32(S1):S51–S68. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01775.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holford TR, Levy DT, McKay LA, et al. Patterns of Birth Cohort–Specific Smoking Histories, 1965–2009. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson CM, Burns DM, Dodd KW, Feuer EJ. Birth-cohort-specific estimates of smoking behaviors for the U.S. population. Risk Analysis. 2012;32(S1):S14–S24. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01703.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wynder EL, Graham EA. Tobacco smoking as a possible etiologic factor in bronchiogenic carcinoma; a study of 684 proved cases. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1950;143:329–336. doi: 10.1001/jama.1950.02910390001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doll R, Hill AB. The mortality of doctors in relation to their smoking habits. A preliminary report. British Medical Journal. 1954;1 (4877):1451–1455. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4877.1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Dept. of Health and Human Services. Reducing the Health Consequences of Smoking: 25 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon Genera. US DHHS, PHS, Centers for Disease Control, Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg MA, Feuer EJ, Yu B, et al. Cohort life tables by smoking status, removing lung cancer as a cause of death. Risk Analysis. 2012;32:S25–S38. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Cancer Society. [Accessed August, 2013];Cancer Prevention Study I. http://www.cancer.org/research/researchtopreventcancer/cancer-prevention-studies.

- 13.American Cancer Society. Current Cancer Prevention Studies. 2013 Aug; http://www.cancer.org/research/researchtopreventcancer/currentcancerpreventionstudies/index.

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed August, 2013];NHANES I Epidemiologic Followup Study (NHEFS) http://www.cancer.org/research/researchtopreventcancer/currentcancerpreventionstudies/index.

- 15.Human Mortality Database. Human Mortality Database 2013. 2013 http://www.motality.org.

- 16.Population Estimates, National Estimates by Age, Sex, Race: 1900–1979 (PE-11) 2013 http://www.census.gov/popest/data/national/asrh/pre-1980/PE-11.html.

- 17.County-Level Population Files-Single Year of Age Groups. 2013 http://seer.cancer.gov/popdata/download.html#state.

- 18.Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Single Year of Age and Sex for the United States, States, and Puerto Rico Commonwealth: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012. 2013 http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk.

- 19.Warner KE. Effects of the antismoking campaign: An update. American Journal of Public Health. 1989;79:144–151. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.2.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses--United States, 2000–2004. Vol. 2008. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Nov 14, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thun MJ, Carter BD, Feskanich D, et al. 50-year trends in smoking-related mortality in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368:351–364. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arias E. United States Life Tables, 2006. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD. Deaths: Final data for 2010. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agaku IT, Vardavas CI, Ayo-Yusuf OA, Alpert HR, Connolly GN. Temporal trends in smokeless tobacco use among US middle and high school students, 2000–2011. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;309(19):1992–1994. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCarthy ME. E-cigarette use doubles among US middle and high school students. British Medical Journal. 2013;11:347. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richardson A, Rath J, Ganz O, Xiao H, Vallone D. Primary and dual users of little cigars/cigarillos and large cigars: demographic and tobacco use profiles. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2013;15(10):1729–1736. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quinn PQ, Hollis JF, Smith KS, et al. Effectiveness of the 5-As Tobacco Cessation Treatments in Nine HMOs. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(2):149–154. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0865-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vidrine JI, Shete S, Cao Y, et al. Ask-Advise-Connect: a new approach to smoking treatment delivery in health care settings. Journal of the American Medical Association Interal Medicine. 2013;173(6):458–464. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy DT, Graham AL, Mabry PL, Abrams DB, Graham AL, Orleans CT. Modeling the Impact of Smoking Cessation Treatment Policies on Quit Rates. Americal Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38(38):S364–S372. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.