Abstract

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is an important risk factor for endocrine cancers; however, the association with thyroid cancer is not clear. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to clarify the association between thyroid cancer and DM.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, PUBMED and EMBASE databases through July 2012, using search terms related to diabetes mellitus, cancer, and thyroid cancer. We conducted a meta-analysis of the risk of incidence of thyroid cancer from pre-existing diabetes. Of 2,123 titles initially identified, sixteen articles met our inclusion criteria. An additional article was identified from a bibliography. Totally, 14 cohort and 3 case-control studies were selected for the meta-analysis. The risks were estimated using random-effects model and sensitivity test for the studies which reported risk estimates and used different definition of DM.

Results

Compared with individuals without DM, the patients with DM were at 1.34-fold higher risk for thyroid cancer (95% CI 1.11–1.63). However, there was heterogeneity in the results (p<0.0001). Sensitivity tests and studies judged to be high quality did not show heterogeneity and DM was associated with higher risk for thyroid cancer in these sub-analyses (both of RRs = 1.18, 95% CIs 1.08–1.28). DM was associated with a 1.38-fold increased risk of thyroid cancer in women (95% CI 1.13–1.67) after sensitivity test. Risk of thyroid cancer in men did not remain significant (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.80–1.53).

Conclusions

Compared with their non-diabetic counterparts, women with pre-existing DM have an increased risk of thyroid cancer.

Introduction

Thyroid cancer incidence has been increasing worldwide since the early 1980s, most dramatically in the past decades [1], [2]. In Korea, the incidence rate of thyroid cancer in adults was about 91 per 100,000 persons in 2010, substantially higher than anywhere else in the world. Thyroid cancer has been most common cancer occurring in Korea since 2005, especially among women. In 2009, a total of 31,811 new incident thyroid cancers were diagnosed; 73.9% (26,682 cases) in women (2009 Cancer Registry data from Korea National Cancer Center). Despite the increase in incidence, the thyroid cancer survival remains high [3], [4].

Risk factors for thyroid cancer are not well established. Only neck irradiation and for follicular thyroid cancer, insufficient iodine intake, are known risk factors for thyroid cancer [5]–[7]. The dramatically increasing incidence of thyroid cancer might be partly attributed to detection bias due to increasing screening by neck ultrasound; however the increase cannot be fully explained by increased medical surveillance or improved detection methods alone [8]. The role of other risk factors in the development of thyroid cancer and in its increasing incidence needs further elucidation. Here we address the possible role of diabetes mellitus (DM).

Type II DM is one of the most rapidly increasing public health issues in Korea, as well as elsewhere. The prevalence of DM is expected to an increase from 2.8% in 2000 to 4.4% in 2030, with the rate increase being greater in developing countries than in developed ones [9]. In Korea, the prevalence rate of DM in adults 30 years of age and older has increased from 1–4% in the 1970s to 9.5% in 2007 (the National Nutrition Survey) [10]. DM has been associated with an increased risk of several types of cancer, including pancreas [11], liver [12], and endometrium. While several observational studies have previously examined cancer risk or mortality [13]–[16], the results in relation to thyroid cancer have not been consistent, due largely to the small number of incidence cases of thyroid cancer in any given study [13], [17], [18]. Although two recent large-sized population-based longitudinal studies indicate that a history of DM may be a risk factor for thyroid cancer [19], [20], this risk may be overestimated in the study of Radiologic Technologists as this is a high risk population. Thus, the present review and meta-analysis was designed to determine whether type II DM effects thyroid cancer incidence and whether the effects differ by gender.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy

We performed a literature search up through August 2012 using the PubMed, Medline and EMBASE databases with the following search terms: (diabetes and thyroid cancer), (diabetes and cancer) (diabetes and thyroid), (type 2 diabetes and cancer), (thyroid cancer and fasting glucose), (thyroid cancer and hyperglycemia), (thyroid cancer and risk factor) and (thyroid cancer and metabolic syndrome). Furthermore, to find any additional published studies, a manual search was also performed by checking all the references of all the studies. All studies included in the meta-analysis were scored for quality using the quality reporting standards for meta-analyses outlined by Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) [21].

Literature search

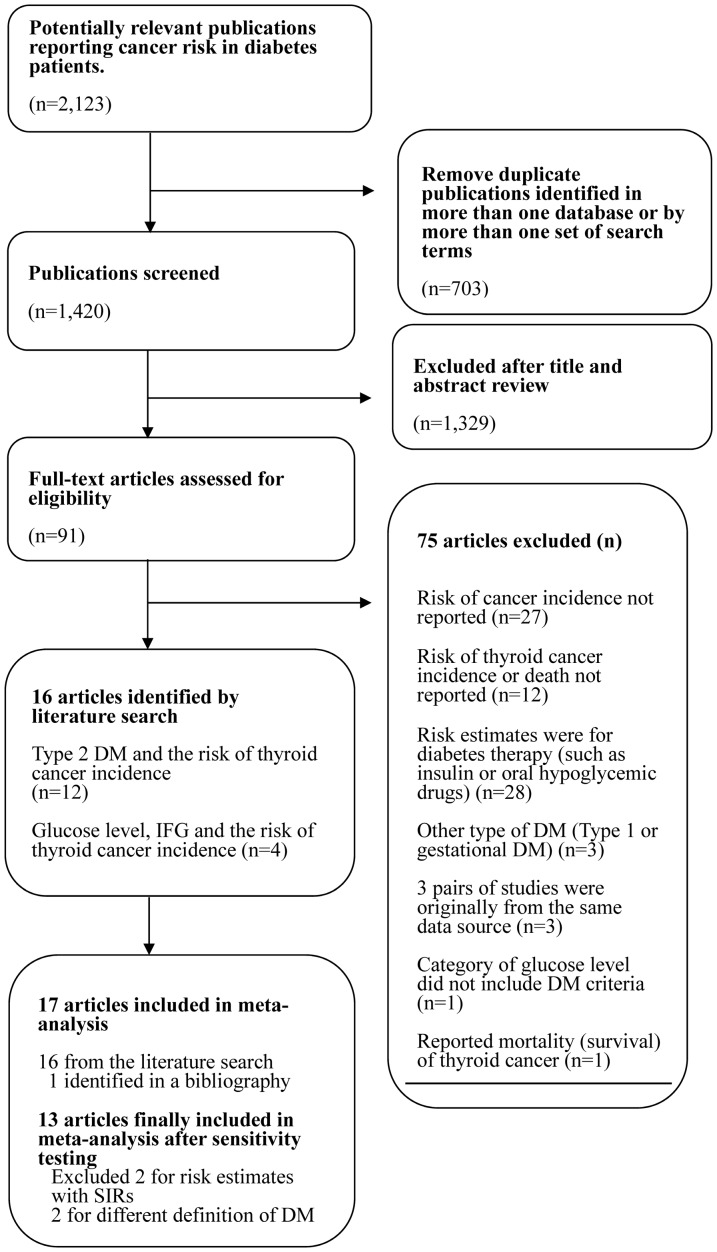

Of 2,123 articles originally identified, we excluded 703 duplicates (i.e., those that appeared in more than one database or from more than one set of search terms) (Figure 1). Another 1,329 articles were excluded after screening the title and abstract. For the remaining 91 articles, we conducted a full-text assessment for relevance. Of these 91, 75 studies were excluded as follows: the studies did not reported the risk of thyroid cancer incidence with a 95% CI (27 studies); the studies analyzed the effects of diabetes therapy (such as insulin or metformin) only (28 studies); the studies did report the risk of thyroid cancer incidence (12 studies); the studies did not address type II DM (3 studies) [22]-[24]; the study populations were originally from the same data source among 6 studies (3 studies) [25]–[27]; or the study examined only thyroid cancer mortality (1 study) [28]; or the categorical levels of glucose such as 2.2–4.1, 4.2–5.2, 5.3–6.0, 6.1–6.9, and 7.0 mmol/L+ (1 study) [29]. Of remained 16 relevant articles, one study [30] showed the results from five prospective studies such as NIH-AARP, USRT, PLCO, AHS, and BCDDP, however we included only PLCO study results in our meta-analysis because the source population from NIH-AARP and USRT were duplicated with the selected two studies [19], [20] and the risk estimates were not estimated from AHS and BCDDP due to few cases. Moreover, we found the additional article [31] by a manual search using the reference lists of 16 articles. Therefore, 17 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Figure 1. Literature search algorithm.

Study selection and assessment

Studies were required to meet the following inclusion criteria to be eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis: case-control studies that recruited thyroid cancer cases and controls without thyroid cancer; or cohort studies conducted among healthy individuals or that were reconstructed among type 2 diabetic patients to estimate the thyroid cancer risk compared with the total population of the country where the study was performed. In addition, studies that compared type 2 DM patients to the source population in order to estimate the risk of thyroid cancer using the standardized incidence ratio (SIR) were also included but these studies were excluded [14], [32] when we performed sensitivity analysis.

The exposure of interest was the presence of pre-existing type 2 DM. If there was lack of the information about whether a diagnosis of type 2 DM had been made, we used the number of patients with impaired fasting glucose levels relative to the reference level identified by the WHO (100<fasting glucose<126 mg/dl). Crude risk estimates for the patients with impaired glucose metabolism, compared with normal glucose levels, were calculated. However, we excluded the studies which used a different or definition of DM [33] or an unavailable glucose level (quintile) in sensitivity analysis [34]. We used the mean level of glucose for each category to justify the patients in normal or abnormal glucose status. Furthermore, if the number of each category divided as the quartile of glucose level, we used the 95 confidence interval to infer the risk in one study [35]. The risk was recalculated by each level of 0.01 mmol/L for glucose level and we estimated the risk by summarized relative risks whose level were higher than the lower limit of confidence interval whom the glucose level were under the confidence interval as the reference.

The main outcome of interest was the reported odd ratios (OR), relative risk (RR), or hazard ratio (HR) or estimates and their corresponding 95% confident intervals (95% CIs). If risk estimates were only given for males and females separately, we recalculated the risk for all patients combined. There were 3 studies that provided risk estimates only for females [13], [35], [36] In addition, there were no observed incident cases among men in 2 studies [20], [35].

The following data were abstracted from each article: the first author's last name, publication year, country where the study was performed, study period, participant's age range, sample size (cases and controls or cohort size, and number with a past history of type 2 DM), variables adjusted for in the analysis, and the RRs and their 95% CIs. The countries with low or high incidence rates of thyroid cancer were classified according to Globocan comparing to the worldwide average incidence (4.0 age-standardized rate per 100,000) [37]. The countries with high incidence included United States [19], [20], [30], [36], [38], Iceland [35], Italy [18], Canada [39], Israel [40], Taiwan [41] and Turkey [33]. Other countries including Sweden [17], [32], [34], Norway [34], Denmark [14], and Japan [13], [31], were classified into “around or lower than worldwide average”. The quality of the study was assessed using the 9-star Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (range: 0 to 9) [21]. Data extraction was conducted independently by two investigators, with disagreements resolved by consensus.

Statistical analysis

We used a random-effect model to obtain the summary relative risk and 95% CI for the association between DM and thyroid cancer risk. Statistical heterogeneity among studies (i.e., whether the differences obtained between studies was due to chance) was evaluated by using the Cochran Q and I2 statistics. For the Q statistic, a p-value<0.10 was considered statistically significant for heterogeneity; for I2, a value>50% is considered a measure of heterogeneity. All HRs from cohort studies and ORs from case-control studies were estimated as RRs. Publication bias was evaluated with the use of the Egger regression asymmetry test in which a p-value less than 0.05 was considered representative of statistically significant publication bias based on a funnel plot.

Subgroup analyses were performed according to the following characteristics: gender (males, females, combined); study designs (cohort or case-control); quality of the study methodology across the studies (6 or more, less than 6); and geographical area (high incidence of thyroid cancer, low incidence of thyroid cancer relative to the global average). All the sub-analyses were performed after excluding 4 studies using the risk estimates with SIRs [14], [32] and the different definition of diabetes [33], [34] for sensitivity analysis. All statistical analyses were performed with the STATA software, version 10 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas).

Results

Table 1 summarizes the study characteristics of the 17 studies included in the meta-analysis. Two studies [14], [32] out of 17 studies used SIRs as the measure of relative risk, and the other two studies [33], [34] used different definitions for DM (also included IFG and IGT or used quintile of glucose level). The 13 studies,which remained after sensitivity analysis, finally consisted of 2 case-control [18], [31] and 11 cohort studies [13], [17], [19], [20], [30], [35], [36], [38]–[41], published between 1992 and 2012. Six studies were performed in the United States and Canada [19], [20], [30], [36], [38], [39], three were in Europe (Sweden, Iceland and Italy) [17], [18], [35] and other four were in Asia (Japan, Israel and Taiwan) [13], [31], [40], [41]. Ten of the studies were deemed of high quality [13], [17], [19], [20], [30], [31], [35], [38], [39], [41] (Table S2).

Table 1. Details of studies on type 2 diabetes for thyroid cancer risk.

| Author [Reference] | Design | Control type or reference population | Country | Age range | Study period | N of thyroid cancer cases | N of controls (or person years) | Comment |

| Cohort studies | ||||||||

| Aschebrook-Kilfoy et al. 2011 [19] NIH-AARP | Cohort | - | US | 50–71 | 1995–2006 | 585 | The NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study cohort [Study qualitya by (Selection:3, Comparability:1, Outcome:2)] | |

| Wideroff et al. 1994 [14] b | Cohort | Danish population | Denmark | - | 1977–1989 | 31 | N/A | Standardized incidence rate Using Danish Central Hospital Discharge Register [Study qualitya by (Selection:3, Comparability:0, Outcome:2)] |

| Adami et al. 1991 [17] | Cohort | Swedish population | Sweden | - | 1984–1991 | 19 | N/A | Using the national population register. [Study quality a by (Selection:4, Comparability:1, Outcome:2)] |

| Chodick et al. 2010 [40] | Cohort | - | Israel | >21 | 2000–2008 | 114 | (671,089) | Using MHS national registry of DM [Study quality a by (Selection:4, Comparability:0, Outcome:1)] |

| Inoue et al. 2010 [13] | Cohort | - | Israel | 40–69 | 1990–2003 | 103 (Women) | (1,002,037) | Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective [Study [Study quality a by (Selection:3, Comparability:1, Outcome:2)] |

| Johnson et al. 2011 [39] | Cohort | - | Canada | - | 1994–2006 | 126 | (185,100) | Using British Columbia Linked Health Database [Study quality a by (Selection:4, Comparability:2, Outcome:2)] |

| Hemminki et al. 2010 [32] b | Cohort | Swedish population | Sweden | >39 | 1964–2006 | 71 (2.9) | 9,298 | Standardized incidence rate, using hospital discharge register linking it to cancer register [Study quality a by (Selection:3, Comparability:1, Outcome:2)] |

| Atchison et al. 2010 [38] | Cohort | - | US | 18∼100 | 1969–1996 | 1,053 | (4,501,578) | Hospital discharge register linking it to cancer register [Study quality a by (Selection:4, Comparability:1, Outcome:2)] |

| Meinhold et al. 2009 [20] USRT study | Cohort | - | US | - | 1982–2006 | 116 (Women) | (90,713) | US Radiologic Technologists Study for occupational irradiation exposure [Study quality a by (Selection:3, Comparability:2, Outcome:2)] |

| Lo et al. 2012 [41] | Cohort | Population in the same database | Taiwan | - | 1996–2009 | 1,309 | 895,434 | Taiwan National Health Research Institute (NHRI) database [Study quality a by (Selection:3, Comparability:2, Outcome:2)] |

| Kabat et al. 2012 [36] | Cohort | - | US | 1993–2009 | 331 (Women) | 159,009 | Women's Health Initiative (WHI) study [Study quality a by (Selection:3, Comparability:2, Outcome:2)] | |

| Stocks et al. 2009 d [34] | Cohort | - | Norway, Sweden, Austria | - | 1972–2005 | 277 | (2,738,701) | The Metabolic syndrome and Cancer project (Me-Can) [Study quality a by (Selection:4, Comparability:1, Outcome:3)] |

| Tulinius et al. 1997 [35] | Cohort | - | Iceland | - | 1967–1995 | 46 (Women) | 22,946 | The Icelandic study of risk factors for cardiovascular disease (Reyjavik Study) [Study quality a by (Selection:4, Comparability:2, Outcome:2)] |

| Kitahara et al, 2012 [30]PLCO study c | Cohort | US | 52–75 | 1993–2009 | 51 | 48,446 | Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial [Study quality a by (Selection:3, Comparability:0, Outcome:2)] | |

| Case-control studies | ||||||||

| Vecchia et al. 1994 [18] | Case-control | Hospital | Italy | <75 | 1983–1992 | 208 | 7,834 | [Study quality by (Selection:1, Comparability:1, Outcome:1)] |

| Kuriki et al. 2007 [31] | Case-control | Hospital | Japan | >18 | 1988–2000 | 215 | 47,768 | Data from the Hospital-Based Epidemiologic Research Program at Aichi Cancer Center, Japan (HERPACC) [Study quality a by(Selection:2, Comparability:2, Outcome:2)] |

| Duran et al. 2012 [33] e , f , | Case-control | Hospital | Turkey | 15–97 | 2003–2009 | 106b | 2,224b | Data from single hospital of clinic of the Medical School at Baskent University [Study quality a by (Selection:3, Comparability:1, Outcome:2)] |

NIH-AARP (National Institutes of Health-American Association of Retired Persons) study; USRT (United States Radiologic Technologists) study; PLCO (Prostate, lung, colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial) study.

Study quality was judged based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (range, 1–9 stars).

Standardized incidence ratio (SIR) per 1,000,000 within reference population.

Prostate, lung, colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO) data.

Participants who were classified into the highest quintile (quintile 5) were regarded as diabetic patients (including level for impaired fasting glucose metabolism).

Participants with Impaired Fasting Glucose (IFG, 100≤FBS or OGTT<125) or Impaired Glucose Tolerance (IGT, 140≤OGTT≤199) by 2009 ADA criteria.

Controls were benign thyroid diseases.

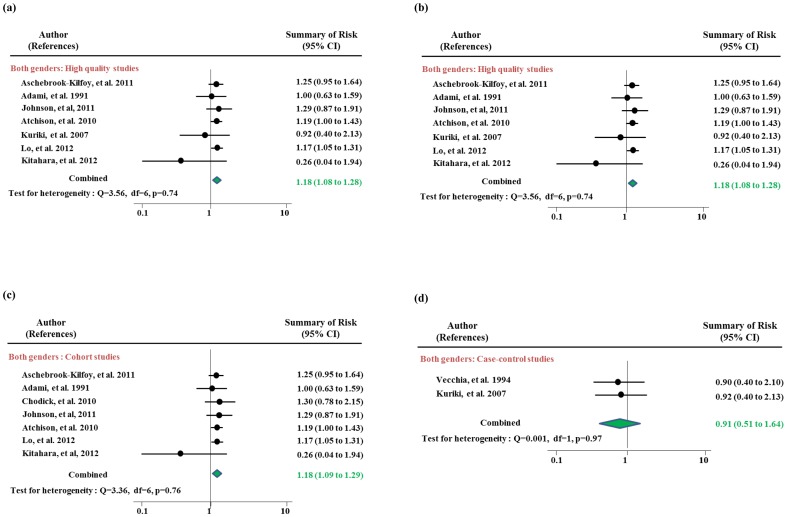

Table 2 and Figure 2 show risk estimates for DM-associated thyroid cancer risk in all studies and subgroups according to study design, geographic region, and study quality. People with type 2 DM were at an increased risk for thyroid cancer relative to non-diabetic people in all studies combined (RR = 1.34, 95% CI 1.11–1.63). However, there was heterogeneity across the studies (p-heterogeneity<0.0001). For the sensitivity analysis, we excluded the studies which reported risk estimates of SIR [14], [32] and had different definition of DM [33], [34]. When we excluded these studies, people in 9 studies remaining after sensitivity testing showed about a 20% increased risk of thyroid cancer associated with pre-existing DM (RR 1.18, 95% CI 1.08–1.28) (Figure 2-(a)). In the cohort studies, DM was associated with a greater increased risk for thyroid cancer (RR 1.18, 95% CI 1.09–1.09) without any heterogeneity (p for heterogeneity = 0.76) and no evidence for publication bias (p by Egger test = 0.39) (Figure 2-(b)). The risk estimate for case-control studies resulted in a relative risk of 0.91 (95% CI 0.51–1.64) which were estimated from the 2 studies. The results for studies from countries with a high incidence of thyroid cancer were similar to the results overall (RR 1.18, 95% CI 1.09–1.29). In low-rate geographic areas, the thyroid cancer risk associated with DM was no longer apparent. In high quality studies, type 2 DM was associated with a RR of thyroid cancer of 1.18 (95% CI 1.08–1.28) after sensitivity testing.

Table 2. Risk estimates for diabetes mellitus-associated thyroid cancer overall and within subgroups.

| N of studies | N of thyroid cancer cases | Summary RR (95% CI) a , c | p-heterogeneity | ||

| All studies | 13 | 4,051 | 1.34 (1.11–1.63) | <0.001 | |

| Sensitivity analysis b | 9 | 3,566 | 1.18 (1.08–1.28) | 0.84 | |

| Study design b | Cohort studies | 7 | 3,143 | 1.18 (1.09–1.29) | 0.76 |

| Case-control studies | 2 | 423 | 0.91 (0.51–1.64) | 0.97 | |

| Geographical area b | High incidence regions | 7 | 3,446 | 1.18 (1.09–1.29) | 0.76 |

| Low incidence regions | 2 | 120 | 0.98 (0.66–1.47) | 0.98 | |

| Study quality b | Score ≥6 | 7 | 3224 | 1.18 (1.08–1.28) | 0.74 |

| Score <6 | 2 | 322 | 1.18 (0.76–1.81) | 0.46 |

All summary ORs/RRs (95% CIs) were calculated by the random-effect model.

We excluded three studies using the risk estimates with SIRs ([14] and [32]) and the different definition of diabetes ([33]was included with IFG and IGT and [34] used quintile of glucose level).

No publication bias by Egger and Begg test (p>0.05).

Figure 2. Meta-analysis of the association between diabetes mellitus and thyroid cancer in men and women: (a) all studies, (b) high quality studies (c) cohort studies and (d) case-control studies.

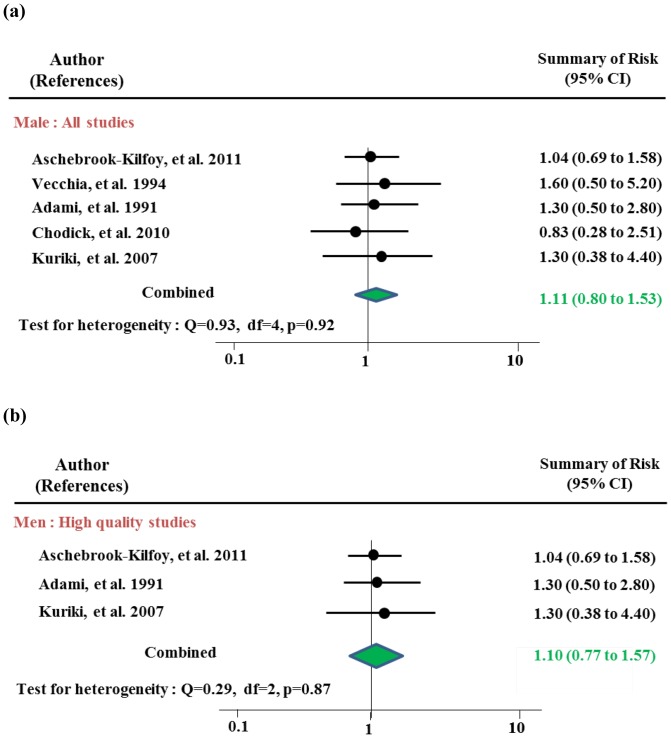

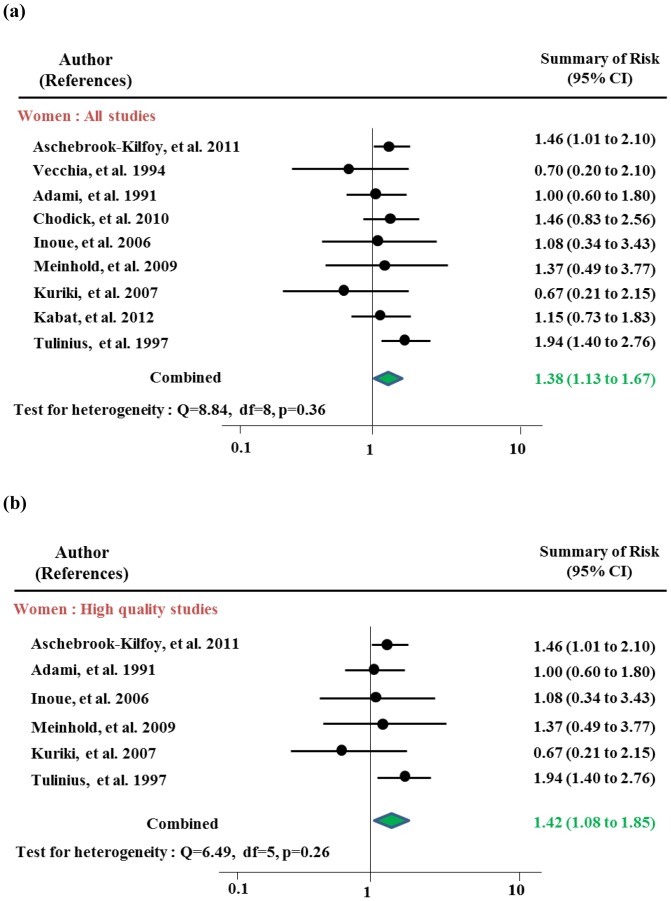

Table 3 and Figure 3 and 4 present risk estimates stratified by gender. After sensitivity testing, women with type 2 DM had an increased risk of thyroid cancer of 1.38 (95% CI 1.13–1.67) overall and 1.42 (95% CI 1.08–1.85) among high quality studies, with risks among the cohort studies and in high incidence rates reached statistical significance Indication of publication was observed both in overall (p by Egger test = 0.01, respectively) which disappeared after excluding studies for sensitivity analysis. No publication bias was observed in sub-analyses. The risks among the cohort studies showed an increased risk of thyroid cancer with RR of 1.45 (95% CI 1.21–1.75). Rates of people in high incidence area were observed with RR of 1.32 (95% CI 1.04–1.68) without any heterogeneity. Men with DM were not at increased risk of thyroid cancer overall (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.80–1.53) or in any of subgroup analysis strata after sensitivity analyses.

Table 3. Gender specific risk estimates for diabetes mellitus-associated thyroid cancer overall and within subgroups.

| N of studies | N of thyroid cancer cases | Summary RR (95% CI) a | p-heterogeneity | ||

| Women | |||||

| All studies | 11 | 1,542 | 1.24 (0.98–1.58) c | 0.11 | |

| Sensitivity analysis b | 9 | 1,244 | 1.38 (1.13–1.67) | 0.36 | |

| Study design b | Cohort studies | 7 | 929 | 1.45 (1.21–1.75) | 0.44 |

| Case-control studies | 2 | 315 | 0.69 (0.30–1.57) | 0.96 | |

| Geographical area b | High incidence regions | 6 | 1,055 | 1.50 (1.23–1.83) | 0.40 |

| Low incidence regions | 3 | 189 | 0.95 (0.60–1.50) | 0.81 | |

| Study quality b | Score ≥6 | 6 | 687 | 1.42 (1.08–1.85) | 0.26 |

| Score <6 | 3 | 557 | 1.20 (0.86–1.69) | 0.52 | |

| Men | |||||

| All studies | 7 | 506 | 1.15 (0.86–1.54) | 0.49 | |

| Sensitivity analysis b | 5 | 219 | 1.11 (0.80–1.53) | 0.92 | |

| Study design b | Cohort studies | 3 | 111 | 1.06 (0.74–1.50) | 0.81 |

| Case-control studies | 2 | 108 | 1.45 (0.62–3.38) | 0.81 | |

| Geographical area b | High incidence regions | 3 | 148 | 1.06 (0.73–1.53) | 0.71 |

| Low incidence regions | 2 | 71 | 1.30 (0.64–2.63) | 1.00 | |

| Study quality b | Score ≥6 | 3 | 123 | 1.10 (0.77–1.57) | 0.87 |

| Score <6 | 2 | 96 | 1.13 (0.51–2.51) | 0.42 |

All summary ORs/RRs (95% CIs) were calculated by the random-effect model

We excluded three studies using the risk estimates with SIRs ([14] and [32]) and the different definition of diabetes ([33] was included with IFG and IGT and [34] used quintile of glucose level)

Publication bias by Egger and Begg test (p<0.05).

Figure 3. Meta-analysis of the association between diabetes mellitus and thyroid cancer in men: (a) all studies and (b) high quality studies.

Figure 4. Meta-analysis of the association between diabetes mellitus and thyroid cancer in women: (a) all studies and (b) high quality studies.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the association between type 2 DM and the incidence of thyroid cancer. The meta-analysis indicates that type 2 DM was associated with a statistically significant increase in thyroid cancer risk of approximately 20% of overall study populations, with a 30% increase among women, but not among men. This association was seen clearly in the cohort studies, in geographic areas in which there is a high incidence of thyroid cancer, and among high quality studies as measured by NOS scale.

A previous pooled analysis of five prospective studies [30] that included NIH-AARP, USRT, PLCO, AHS, and BCDDP reported no evidence of an association between a history of DM and thyroid cancer risk (HR = 1.08, 95% CI 0.83–1.40). The risk among women was higher risk (HR 1.19, 95% CI 0.84–1.69) but remained statistically non-significant. Subgroup analyses by smoking status, histologic type of thyroid cancer, educational attainment, and other factors all suggested no significant associations. The lack of association might be explained by the small number of cancer cases among the exposed group. In AHS and BCDDP, there were no thyroid cancer cases developing among persons with DM, and PLCO had only 1 thyroid cancer case in this group. In addition, all of these studies were conducted in the US, possibly limiting the heterogeneity of exposure and limiting statistical power. In our meta-analysis, we included studies conducted throughout the world, providing substantial population heterogeneity, and demonstrating that the risk associated with DM is most pronounced among women residing in areas which experience high rates of thyroid cancer relative to other geographic areas of the world.

Several biological mechanisms may account for this association. The first is via activation of insulin and the IGF pathway which share affinity with insulin and important to cell proliferation and apoptosis [42]. The chronically elevated circulating insulin levels associated with DM [43] may influence thyroid cancer risk mediated by insulin receptors overexpressed by cancer cells. IGF-1, a well-known pathway with an affinity for insulin, is also critical to cell proliferation and apoptosis and has been shown to be related to various types of cancer, such as breast and colon [44], [45]. A number of studies have also suggested that thyroid cancer risk is increased among persons with Metabolic Syndrome, which includes a glucose level in the diagnostic criteria [46]–[52]. Chronic metabolic disturbances, which are characteristics of type 2 DM and include aberrations in the insulin-like growth factor pathway, also affect steroid hormone metabolism suggesting that this pathway may also be involved [53]–[55].

A second possible mechanism involves long-term exposure to elevated thyroid-stimulating hormones (TSH). Concordant with the increase in anti-thyroid antibody level, primary hypothyroidism and the elevation of TSH, is 3 times more frequent in type 2 diabetics than in non-diabetics [56]. Even though the roles of TSH in thyroid carcinogenesis have not been established, there were several studies which reported the association of autonomous TSH regulation with reduction in thyroid cancer risk [57], or prediction of aggressive carcinoma of thyroid with higher TSH concentration [58]. Chronic high serum TSH concentration also predicted higher likelihood of differentiated thyroid cancer in that people whose TSH level were above the mean of population had higher risk of thyroid cancer compared to those with lower TSH level than the mean [59].

A third possible mechanism involves the impact of hyperglycemia on tumor cell growth and proliferation [60]. The possible mechanism is an increased oxidative stress [61] and as a metabolic factor, glucose can increase the production of reactive oxygen species, especially nitric oxide [62]. These seem to be much more complex because glucose metabolism is also influenced by sex hormones [63], [64]. The relationship between female reproductive hormones, glucose and thyroid cancer is still unclear. Recently, intracellular deiodinase, a regulating enzyme that controls expression of intracellular thyroid hormone levels, has been implicated as a potential carcinogenic mechanism in relation to diabetes and thyroid cancer [65], [66].

In our meta-analysis, the overall results showed heterogeneity across the studies. The heterogeneity problems disappeared after sensitivity analysis in all sub-group analyses and publication bias did not appear to be present. There were 2 studies which were excluded for using different criteria for DM in sensitivity analysis. In one study, blood glucose levels were inversely associated with thyroid cancer in women [34]. Since the quintile cut-points in this study were not provided, whether any of the quintiles were indicative of DM is not clear and may have resulted in the observed inverse association. Another one [33] is a case-control study with study population who conducted fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) after confirmed thyroid mass. They reported the risk of malignant neoplasm compared with that of benign thyroid tumors as an exposure for glucose metabolism disorder, such as impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and impaired fasting glucose (IFG) among those patients.

While the results for men was consistent, and there was no evidence for between study heterogeneity or publication bias, the lack of a statistically significant association between DM and thyroid cancer risk in this subgroup may simply be a result of a smaller number of cases and lack of information for prevalence of DM.

The possibility that the occurrence of thyroid cancer precedes the development of DM cannot be entirely excluded. The mean age for diagnosis of type 2 DM is similar to that of thyroid cancer around the age of 40 and since thyroid cancer is usually a slow-growing tumor and the diagnosis of DM can be delayed due to its often silent nature, the temporal sequence of which came first or the concurrent development of both cannot be ruled out even in cohort studies. The accurate time between incidence of DM and thyroid cancer is an important element in evaluating this relationship but is beyond the scope of this meta-analysis to examine it. Although, when provided, we used study results which excluded early incident cases.

Moreover, how long subjects were comorbid with DM and which drugs they used were not available in studies. Neither could we estimate whether they were under-controlled with DM or not. As hemoglobin A1C, one of the useful parameters that are usually examined for regular follow-up in clinics, was not available in the studies, we could not estimate any correlation of thyroid cancer risk with HbA1C. Duration of prevalent DM of participants, which might be related to the risk of thyroid cancer in the aspect of dose-response relationship, could not be taken into the analyses, either.

There are some additional potential limitations to this meta-analysis. Some studies which were included were based on patients' self-report. In addition, information on diabetes treatment was unknown, thus, controlled vs uncontrolled DM could not be distinguished. Some studies did not adjust for potentially confounding factors, such as obesity and age. In several studies when we estimated the RRs using the frequency data from the published tables, it was not available to adjust for potential confounding effects. Since DM is represented in most studies as a yes/no variable, we could not we could not characterize the shape of curve associated with different degrees of DM. Moreover, the overall results showed heterogeneity and publication bias was indicated across the studies among women. However, it was improved after excluding studies for sensitivity analysis. Finally, we were unable to conduct sub-group analysis for pathophysiologic types of thyroid cancer, thus, potentially attenuating risk estimates.

Nevertheless, this study had several strengths. We were able to conduct gender-specific analyses which suggested that the DM-thyroid cancer association may be more pronounced among women. If this is not simply a matter of statistical power, it may have implications for the mechanisms involved. In addition, we included studies that reported only glucose levels as the exposure of interest. We performed a sub-group analysis according to the type of risk estimates and found that the risk type did not influence on the direction or strength of thyroid cancer risk.

Our results indicate that DM may increase the risk of thyroid cancer in women. Thus, given the rapidly increasing risk of thyroid cancer worldwide, regular thyroid examination for type 2 DM patients may be worthwhile until these results can be further confirmed or clarified.

Supporting Information

Risk estimates and their 95% confidence intervals in previous studies in relation to association between diabetes mellitus and thyroid cancer risk.

(DOCX)

Judged study quality based on the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (range, 1-9 stars),

(DOCX)

PRISMA Checklist 2009.

(DOCX)

Funding Statement

This research was supported by BRL (Basic Research Laboratory) program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2012-0000347) and by the Research Grant Number CB-2011-03-01 of the Korean Foundation for Cancer Research. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Kilfoy BA, Zheng T, Holford TR, Han X, Ward MH, et al. (2009) International patterns and trends in thyroid cancer incidence,1973–2002. Cancer Causes Control 20: 525–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kilfoy BA, Devesa SS, Ward MH, Zhang Y, Rosenberg PS, et al. (2009) Gender is an age-specific effect modifier for papillary cancers of the thyroid gland. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 18: 1092–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jung K-W, Park S, Kong H-J, Won Y-J, Boo Y-K, et al. (2010) Cancer Statistics in Korea: Incidence, Mortality and Survival in 2006–2007. Journal of Korean Medical Science 25: 1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korean National Cancer Information Center, Cancer Statistics in Korea, 2009; 2011.

- 5. Ron E (1987) A population-based case-control study of thyroid cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 79: 1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ron E, Schneider AB (2006) Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. New York: Oxford University Press.

- 7. Hirohata T (1976) Radiation Carninogenesis. Semin Oncol 3: 25–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Busco S, Paolo GR, Isabella S, Pezzotti P, Buzzoni C, et al. (2013) Increased incidence of thyroid cancer in Latina, Italy: A possible role of detection of subclinical disease. Cancer Epidemiology 37: 262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H (2004) Global prevalence of diabetes. Diabetes Care 27: 1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korea centers for Disease Control & Prevention, In-depth analysis report on the examination part of the third national health and nutrition examination survey; 2007.

- 11. Ben Q, Xu M, Ning X, Liu J, Hong S, et al. (2011) Diabetes mellitus and risk of pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Cancer 47: 1928–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yang WS, Va P, Bray F, Gao S, Gao J, et al. (2011) The role of pre-existing diabetes mellitus on hepatocellular carcinoma occurrence and prognosis: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. PLoS ONE 6: e27326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Inoue M, Iwasaki M, Otani T, Sasazuki S, Noda M, et al. (2006) Diabetes mellitus and the risk of cancer. Arch Intern Med 166: 1871–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wideroff L, Gridley G, Chow WH, Linet M, Keehn S, et al. (1997) Cancer Incidence in a population-based cohort of patients hospitalized with diabetes mellitus in Denmark. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 89: 1360–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davey-Smith G, Egger M, Shipley MJ, Marmot M (1992) Post-challenge glucose concentration, impaired glucose tolerance, diabetes, and cancer mortality in men. Am J Epidemiol 136: 1110–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weiderpass E, Gridley G, Nyren O, Pennello G, Landstrom AS, et al. (2001) Cause-specific mortality in a cohort of patients with diabetes mellitus: a population-based study in Sweden. J Clin Epidemiol 54: 802–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Adami HO, McLaughlin J, Ekbom A, Berne C, Silverman D, et al. (1991) Cancer risk in patients with diabetes mellitus. Cancer Causes & Control 2: 307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vecchia CL, Negri E, Franceschi S, D'Avanzo B, Boyle P (1994) A case -control study of diabetes mellitus and cancer risk. Br J Cancer 70: 950–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, Sabra MM, Brenner A, Moore SC, Ron E, et al. (2011) Diabetes and Thyroid Cancer Risk in the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study. Thyroid 21: 957–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Meinhold CL, Ron E, Schonfeld SJ, Alexander BH, Freedman DM, et al. (2009) Nonradiation Risk Factors for Thyroid Cancer in the US Radiologic Technologists Study. American Journal of Epidemiology 171: 242–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stang A (2010) Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. European Journal of Epidemiology 25: 603–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sella T, Chodick G, Barchana M, Heymann AD, Porath A, et al. (2011) Gestational diabetes and risk of incident primary cancer: a large historical cohort study in Israel. Cancer Causes & Control 22: 1513–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shu X, Ji J, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K, et al. (2010) Cancer risk among patients hospitalized for Type 1 diabetes mellitus: a population-based cohort study in Sweden. Diabetic Medicine 27: 791–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zendehdel K (2003) Cancer Incidence in Patients With Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: A Population-Based Cohort Study in Sweden. CancerSpectrum Knowledge Environment 95: 1797–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Almquist M, Johansen D, Björge T, Ulmer H, Lindkvist B, et al. (2011) Metabolic factors and risk of thyroid cancer in the Metabolic syndrome and Cancer project (Me-Can). Cancer Causes & Control 22: 743–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kabat GC, Kim MY, Thomson CA, Luo J, Wactawski-Wende J, et al. (2012) Anthropometric factors and physical activity and risk of thyroid cancer in postmenopausal women. Cancer Causes & Control 23: 421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kitahara CM, Platz EA, Freeman LEB, Hsing AW, Linet MS, et al. (2011) Obesity and Thyroid Cancer Risk among U.S. Men and Women: A Pooled Analysis of Five Prospective Studies. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 20: 464–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu X, Ji J, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Hemminki K (2012) The impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus on cancer-specific survival. Cancer 118: 1353–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rapp K, Schroeder J, Klenk J, Ulmer H, Concin H, et al. (2006) Fasting blood glucose and cancer risk in a cohort of more than 140,000 adults in Austria. Diabetologia 49: 945–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kitahara CM, Platz EA, Beane Freeman LE, Black A, Hsing AW, et al. (2012) Physical activity, diabetes, and thyroid cancer risk: a pooled analysis of five prospective studies. Cancer Causes & Control 23: 463–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kuriki K, Hirose K, Tajima K (2007) Diabetes and cancer risk for all and specific sites among Japanese men and women. Eur J Cancer Prev 16: 83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hemminki K, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K (2010) Risk of Cancer Following Hospitalization for Type 2 Diabetes. The Oncologist 15: 548–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Duran AO, Anil C, Gursoy A, Nar A, Altundag O, et al. (2012) The relationship between glucose metabolism disorders and malignant thyroid disease. International Journal of Clinical Oncology 18: 585–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stocks T, Rapp K, Bjørge T, Manjer J, Ulmer H, et al. (2009) Blood Glucose and Risk of Incident and Fatal Cancer in the Metabolic Syndrome and Cancer Project (Me-Can): Analysis of Six Prospective Cohorts. PLoS Medicine 6: e1000201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tulinius H, Sigfusson N, Sigvaldason H, Bjarnadottir K, Tryggvadottir L (1997) Risk factors for malignant diseases: a cohort study on a population of 22,946 Icelanders. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 6: 863–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kabat GC, Kim MY, Wactawski-Wende J, Rohan TE (2012) Smoking and alcohol consumption in relation to risk of thyroid cancer in postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiology 36: 335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, et al. (2013) GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013 Available: http://globocaniarcfr.

- 38. Atchison EA, Gridley G, Carreon JD, Leitzmann MF, McGlynn KA (2011) Risk of cancer in a large cohort of U.S. veterans with diabetes. International Journal of Cancer 128: 635–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Johnson JA, Bowker SL, Richardson K, Marra CA (2011) Time-varying incidence of cancer after the onset of type 2 diabetes: evidence of potential detection bias. Diabetologia 54: 2263–2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chodick G, Heymann AD, Rosenmann L, Green MS, Flash S, et al. (2010) Diabetes and risk of incident cancer: a large population-based cohort study in Israel. Cancer Causes & Control 21: 879–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lo S-F, Chang S-N, Muo C-H, Chen S-Y, Liao F-Y, et al.. (2012) Modest increase in risk of specific types of cancer types in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. International Journal of Cancer n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42. Hard GC (1998) Recent developments in the investigation of thyroid regulation and thyroid carcinogenesis. Environ Health Perspect 106: 427–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bach L, Rechler M (1992) Insulin-like growth factors and diabetes. Diabetes Metab Rev 8: 229–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hankinson SE, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Michaud DS, et al. (1998) Circulating concentrations of insulin-like growth factor-I and risk of breast cancer. Lancet 351: 1393–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ma J, Pollak MN, Giovannucci E, Chan JM, Tao Y, et al. (1999) Prospective study of colorectal cancer risk in men and plasma levels of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and IGF-binding protein-3. J Natl Cancer Inst 91: 620–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hsu IR, Kim SP, Kabir M, Bergman R (2007) Metabolic syndrome, hyperinsulinemia, and cancer. Am J Clin Nutr 86: 867–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Borena W, Stocks T, Jonsson H, Strohmaier S, Nagel G, et al. (2010) Serum triglycerides and cancer risk in the metabolic syndrome and cancer (Me-Can) collaborative study. Cancer Causes Control 22: 291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gursoy A (2010) Rising thyroid cancer incidence in the world might be related to insulin resistance. Med Hypotheses 74: 35–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Paes JE, Hua K, Nagy R, Kloos RT, Jarjoura D, et al. (2010) The relationship between body mass index and thyroid cancer pathology features and outcomes: a clinicopathological cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95: 4244–4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wolin KY, Carson K, Colditz G (2010) Obesity and cancer. Oncologist 15: 556–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Potenaza M, Via MA, Yanagisawa R (2009) Excess thyroid hormone and carbohydrate metabolism. Endocr Pract 15: 254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Udiong CE, Udoh AE, Etukudoh M (2007) Evaluation of thyroid function in diabetes mellitus in Calabar, Nigeria. IJCB 22: 74–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Xue F, Michels K (2007) Diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and breast cancer: A review of the current evidence. Am J Clin Nutr 86: 823–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Giovannucci E, Michaud D (2007) The role of obesity and related metabolic disturbances in cancers of the colon, prostate, and pancreas. Gastroenterology 132: 2008–2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hjartåker A, Langseth H, Weiderpass E (2008) Obesity and diabetes epidemics: Cancer repercussions. Adv Exp Med Biol 630: 72–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tamez-Pérez HE, Martínez E, Quintanilla-Flores DL, Tamez-Peña AL, Gutiérrez-Hermosillo H, et al. (2012) The rate of primary hypothyroidism in diabetic patients is greater than in the non-diabetic population. An observational study. Med Clin 138: 475–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fiore E, Rago T, Provenzale MA, Scutari M, Ugolini C, et al. (2009) Lower levels of TSH are associated with a lower risk of papillary thyroid cancer in patients with thyroid nodular disease: thyroid autonomy may play a protective role. Endocr Relat Cancer 16: 1251–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Boelaert K (2009) The association between serum TSH concentration and thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 16: 1065–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Haymart MR, Repplinger DJ, Leverson GE, Elson DF, Sippel RS, et al. (2008) Higher serum thyroid stimulating hormone level in thyroid nodule patients is associated with greater risks of differentiated thyroid cancer and advanced tumor stage. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93: 809–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dang CV, Semenza GL (1999) Oncogenic alterations of metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci 24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61. Shih S-R, Chiu W-Y, Chang T-C, Tseng C-H (2012) Diabetes and Thyroid Cancer Risk: Literature Review. Experimental Diabetes Research 2012: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cowey S, Hardy RW (2006) The metabolic syndrome: A high-risk state for cancer? Am J Pathol 169: 1505–1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Saad F, Gooren L (2009) The role of testosterone in the metabolic syndrome: a review. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 114: 40–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ropero AB, Alonso-Magdalena P, Quesada I, Nadal A (2008) The role of estrogen receptors in the control of energy and glucose homeostasis. Steroids 73: 874–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kohrle J (2007) Thyroid hormone transporters in health and disease: advances in thyroid hormone deiodination. Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 21: 173–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kohrle J (1999) Local activation and inactivation of thyroid hormones: the deiodinase family. Mol Cell Endocrinol 151: 103–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Risk estimates and their 95% confidence intervals in previous studies in relation to association between diabetes mellitus and thyroid cancer risk.

(DOCX)

Judged study quality based on the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (range, 1-9 stars),

(DOCX)

PRISMA Checklist 2009.

(DOCX)