Abstract

Purpose

Weill-Marchesani syndrome (WMS) is a rare connective tissue disorder, characterized by short stature, microspherophakic lens, and stubby hands and feet (brachydactyly). WMS is caused by mutations in the FBN1, ADAMTS10, and LTBP2 genes. Mutations in the LTBP2 and ADAMTS17 genes cause a WMS-like syndrome, in which the affected individuals show major features of WMS but do not display brachydactyly and joint stiffness. The main purpose of our study was to determine the genetic cause of WMS in an Indian family.

Methods

Whole exome sequencing (WES) was used to identify the genetic cause of WMS in the family. The cosegregation of the mutation was determined with Sanger sequencing. Reverse transcription (RT)–PCR analysis was used to assess the effect of a splice-site mutation on splicing of the ADAMTS17 transcript.

Results

The WES analysis identified a homozygous novel splice-site mutation c.873+1G>T in a known WMS-like syndrome gene, ADAMTS17, in the family. RT–PCR analysis in the patient showed that exon 5 was skipped, which resulted in the deletion of 28 amino acids in the ADAMTS17 protein.

Conclusions

The mutation in the WMS-like syndrome gene ADAMTS17 also causes WMS in an Indian family. The present study will be helpful in genetic diagnosis of this family and increases the number of mutations of this gene to six.

Introduction

Weill-Marchesani syndrome (WMS, OMIM 277600) is a rare connective tissue disorder, characterized by microspherophakia, severe myopia, acute and/or chronic glaucoma, and cataract [1,2]. Other symptoms include brachydactyly and short stature. Patients may also have stiff joints and thickened skin, especially on the hands. Occasionally, cardiac defects or an abnormal heart rhythm can occur in people with WMS [3-6]. Despite clinical homogeneity, two modes of inheritance have been reported for WMS: autosomal dominant (AD) and autosomal recessive (AR). Although AD WMS is caused due to mutations in the fibrillin 1 (FBN1; gene ID 2200, OMIM 134797) gene located on chromosome 15q21.1 [7], AR WMS results due to mutations in the ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 10 (ADAMTS10; gene ID 81794, OMIM 608990) gene located on chromosome 19p13.2 [8] and the latent transforming growth factor-beta-binding protein 2 (LTBP2; gene ID 4053, OMIM 602091) gene on chromosome 14q24 [9], which demonstrates genetic heterogeneity for WMS. Mutations in the LTBP2 [9] and ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 17 (ADAMTS17; gene ID 170691, OMIM 607511) gene located on chromosome 15q24 result in a WMS-like syndrome [10], in which the affected individuals show major features of WMS but do not display brachydactyly and decreased joint flexibility. Mutations in LTBP2 also cause primary congenital glaucoma 3D (PCG) [11,12], isolated microspherophakia [13], and megalocornea, microspherophakia, ectopia lentis, and secondary glaucoma [14]. We report the genetic analysis of an Indian family with WMS, using whole exome sequencing.

Methods

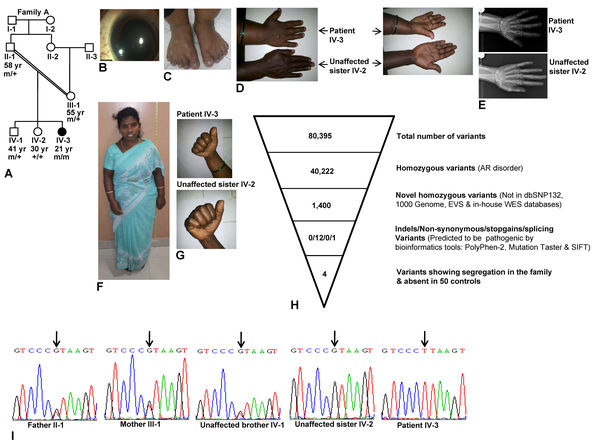

We recruited a 21-year old female patient along with her 58-year old unaffected father, 55-year old unaffected mother, 41-year old unaffected brother and 30-year old unaffected sister (Figure 1A) at the Bangalore West Lions Superspeciality Eye Hospital, Bangalore in April 1999 for decreased vision in the right eye for two years. The family belongs to the city of Bangalore, state of Karnataka, India. On examination, in the right eye there was no perception of light. She improved to 6/9, N8 vision in the left eye with a correction of −10 D (lenticular myopia). The anterior segment examination showed the right eye had exotropia and a fixed dilated pupil. In the left eye, the pupil reacted normally. There was microspherophakia (Figure 1B) with iridodonesis and phacodonesis in both eyes. Gonioscopy showed grade 2 angles in the right eye with peripheral anterior synechiae and grade 2 angles with no synechiae in the left eye. Intraocular pressure (IOP) was 23 mmHg in the right eye and 16 mmHg in the left eye. Fundus evaluation with indirect ophthalmoscopy showed glaucomatous optic atrophy in the right eye and glaucomatous cupping (CD 0.6–0.7) in the left eye. The axial length was 22.5 mm and 21.65 mm in the right eye and the left eye, respectively. She had short stature (131 cm), brachydactyly, and the absence of joint stiffness (Figure 1C–G). There was no cardiac abnormality in the patient. These features suggested that the patient was affected with WMS.

Figure 1.

Clinical phenotype and whole exome sequence analysis. A: Pedigree diagram of family A. B: Microspherophakic lens in the right eye. C: Brachydactyly of the toes. D: Dorsal and ventral sides of hands from the patient and her unaffected sister to show brachydactyly only in the patient. E: X-ray images of the hands of the patient and her unaffected sibling to show brachydactyly in the patient. Both images are at the same magnification. F: Short stature. G: The absence of stiffness of joints in the patient and her unaffected sister is shown by the ability to make fists. H: Whole exome sequencing (WES) data. I: Sequencing chromatograms of individuals from family A. Arrows mark the nucleotide change G>T. + and m represent the wild-type and mutant alleles, respectively. The age of individuals in years is given below the symbols.

Her father (II:1), mother (III:1), unaffected brother (IV:1), and unaffected sister (IV:2) were 150, 140.2, 158.50, and 155.5 cm tall, respectively. None of her parents and siblings had any ocular, joint, and cardiac problems, except her father had undergone cataract surgery for both eyes at the age of 48. The parents of the patient are uncle and niece.

The patient was advised and had undergone Nd:Yag peripheral iridotomy in the left eye and was put on Glucomol (timolol maleate, Allergan, Bangalore, India) eye drops for the left eye. The patient was followed up regularly for IOP and fundus evaluation. Her IOP was 40 mmHg and 34 mmHg in the right eye and the left eye, respectively, in August 2000. Since the IOP was not controlled by maximum medical management, transscleral cyclophotocoagulation was performed for the right eye to decrease the pressure and control the pain. In April 2001, trabeculectomy was performed in the left eye. The IOP was under control at 10 mmHg in subsequent follow-ups. The patient’s vision decreased in the left eye due to cataract changes, and the patient underwent lens aspiration with scleral-fixated intraocular lens implantation in July 2009. She has been on a regular follow-up schedule for vision, IOP, and fundus since then. A retinal hole was detected in her left eye in June 2013 for which a prophylactic laser procedure was performed. There is no history of retinal detachment. On her last visit in December 2013, her unaided vision in the left eye was 6/9 with IOP of 12 mmHg in both eyes and stable retina in the left eye.

This study was approved by an Institution Review Board (an Ethics Committee) and that the study adhered to the tenets of Declaration of Helsinki and the ARVO statement on human subjects. Three to five ml of blood was drawn from each individual in a sodium-EDTA Vacutainer tube (Beckton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) for DNA isolation, using the Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Since the cost of sequencing 101 coding exons of four WMS and WMS-like syndrome genes (viz., ADAMTS10, ADAMTS17, LTBP2, and FBN1) was high, we used whole exome sequencing (WES) on patient IV:3 to find the genetic cause of WMS in this family. For WES, 1 μg of total genomic DNA from the patient was randomly fragmented, size selected to 350–400 bp products, and ligated to adapters on both ends. The resulting library was then amplified and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencer (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA) and run to 45.90X coverage. The resulting reads with an average read length of 101 base pairs were mapped to the human genome (UCSC human genome hg19 build) with the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) program. SNPs and coding indels were detected with the SAMTOOLS program. All genetic variants were then compared to those in dbSNP132, exome variant server (EVS), the 1000 Genomes project, and in-house WES databases to determine if they were known or novel. The pathogenicity of the variants was tested with PolyPhen-2, Mutation Taster, and SIFT bioinformatics tools. The domain structure of the ADAMTS17 protein (GenBank accession number NP_620688.2) was identified using the Pfam program.

Specific coding regions of the ADAMTS17, calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ID (CAMK1D; gene ID 57118, OMIM 607511), pyridine nucleotide-disulphide oxidoreductase domain 2 (PYROXD2; gene ID 84795), and signal-induced proliferation-associated 1 like 3 (SIPA1L3; gene ID 23094) genes were amplified using gene-specific primers to confirm the variants identified with WES. Primer pairs were designed using gene sequences from the UCSC Bioinformatics site (http//genome.ucsc.edu/). The sequences and PCR conditions of the primers are provided in Table 1. Variants were confirmed by sequencing the PCR products from the patient on an ABIprism A370-automated sequencer (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA). PCR was performed using a standard laboratory procedure. Once a mutation (variant) was identified, we then examined 50 ethnically matched controls for the presence of the mutation, using restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis or Sanger sequencing.

Table 1. Details of PCR primers used to confirm the variants.

| Gene | GenBank accession number | Exon | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) | Tm (°C) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ADAMTS17 |

NM_139057 |

5 |

F:TCTTTTCTGTGTCCCAAGTTCCCAT

R:ACAGAGAGTGACGGAGACTGGCA |

64 |

295 |

|

CAMK1D |

NM_020397 |

4 |

F:GGGCAACATCTCAATCTGAAGATGG

R:ACTCTACATCAGAGCAGCTGCATG |

60 |

372 |

|

PYROXD2 |

NM_032709 |

9 |

F:GGGCTGAAGATCAAGATGGAAAGGA

R:TCCCCTCATGGCCCCTCTGTTCA |

60 |

352 |

| SIPA1L3 | NM_015073 | 9 | F:AGAGTGAGACCTGTCTCGATAAAACA R:CTGCACTGTGCTGCTCAGCGCCA | 60 | 442 |

Abbreviations: F, forward primer; R, reverse primer; bp, base pairs; and Tm, Annealing temperature.

To determine the effect of a splice-site mutation on the splicing of the ADAMTS17 transcript (NM_139057.2), total RNA was isolated from peripheral blood samples using the Tri-Reagent BD (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Total RNA was then converted into the first-strand cDNA using a RevertAid H Minus First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Fermentas, Burlington, Canada). Primers specific to exons 4 (5′-ACG CCG ACA TGG TGC AGT ACC AC-3′) and 8 (5′-GGC GAT GGT AAA GGC CAA ATT GAG) were used in the reverse transcription (RT)–PCR analysis, and the amplicons were visualized in a 1.5% agarose gel with ethidium bromide.

Results and Discussion

The WES analysis of patient IV:3 yielded 80,395 variants (Figure 1H). Since WMS is an autosomal recessive disorder, we looked for homozygous variants and identified 40,222 homozygous variants (Figure 1H). By comparing these variants to known variant databases, we identified 1,400 novel homozygous variants (Figure 1H). We then limited our analysis to novel homozygous indels, non-synonymous, stop gain, and splicing variants because they are more likely to be pathogenic. This filtering led to the identification of 13 variants: 12 non-synonymous and one splice variants (Figure 1H). Using segregation analysis of the variants in the family, and the PolyPhen-2, Mutation Taster, and SIFT bioinformatics tools, we identified four novel homozygous variants in four genes in the patient (Figure 1H; Table 2). One of the variants, the splice-site mutation c.873+1G>T in intron 5, was in a known WMS-like syndrome gene ADAMTS17 in the patient in a 1.21 Mb homozygous region (ch15: 100,340,228–101,550,858). None of the other WMS and WMS-like syndrome genes (ADAMTS10, LTBP2, and FBN1) showed a mutation in the patient. Both parents (II:1 and III:1) and an unaffected brother (IV:1) were heterozygous for the mutation, and an unaffected sister (IV:2) was homozygous for the wild-type allele (Figure 1I). The mutation created a novel restriction enzyme site for Bsp TI. Therefore, the digestion of the 295 bp amplicon from the mutant allele is expected to generate two fragments of 177 bp and 118 bp. We then developed a Bsp TI RFLP analysis and did not detect the mutation in 50 ethnically matched controls. This mutation was not observed in the 1000 Genome and EVS databases.

Table 2. Bioinformatics analysis of the novel homozygous variants.

| Gene | Accession Number | Variation | PolyPhen-2 | Mutation Taster | SIFT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ADAMTS17 |

NM_139057.2 |

c.873+1G>T |

- |

Disease causing

(p value 1) |

- |

|

CAMK1D |

NM_020397.2 |

c.326G>A (p.R109Q) |

Probably damaging

(score 1.00) |

Disease causing

(p value 0.99) |

Damaging

(score 0.03) |

|

PYROXD2 |

NM_032709.2 |

c.847G>A (p.V283I) |

Probably damaging

(score 0.907) |

Disease causing

(p value 0.99) |

Damaging (score 0.01) |

| SIPA1L3 | NM_015073.1 | c.2488G>A (p.E830K) | Possibly damaging (score 0.617) | Disease causing (p value 0.99) | Damaging (score 0.01) |

Note: PolyPhen-2 score ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 is neutral, less than 0.14 is benign, 0.14–0.84 is possibly damaging, and 0.85–1.0 probably damaging. Mutation Taster p value (probability) ranges from 0 to one, where 0 is polymorphism, and 1 is disease causing. SIFT score ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 is damaging and 1 is neutral.

Three other novel homozygous variants of unknown significance in three other genes [c.326G>A (p.R109Q) in CAMK1D located on chromosome 10p13, c.847G>A (p.V283I) in PYROXD2 located on chromosome 10q24.2 and c.2488G>A (p.E830K) in SIPA1L3 located on chromosome 19q13.13] were also identified. These three variants were not observed in 50 ethnically matched controls, and were predicted to be damaging by bioinformatics tools (Table 2). These variants were not observed in the 1000 Genome and EVS databases. Although these variants could be low-frequency polymorphisms in the southern Indian population, we cannot formally exclude that they contribute to some aspects of the phenotype.

Morales et al. [10] have earlier identified three homozygous mutations [c.2458_2459insG (p.E820Gfs*23), c.1721+1G>A and c.760C>T (p.Q254*)] in the ADAMTS17 gene in three Saudi Arabian families with WMS-like syndrome. Khan et al. [15] subsequently identified a homozygous novel mutation, c.652delG (p.Asp218Thrfs*41), in a Saudi Arabian family. Interestingly, a splice-site mutation, c.1473+1 G>A, in the ADAMTS17 gene has been reported to be widespread among dog breeds with primary lens luxation [16,17].

Seven patients from three Saudi Arabian families with WMS-like syndrome with mutations in the ADAMTS17 gene had short stature, microspherophakia, myopia, and high IOP, but did not have brachydactyly, joint stiffness, and congenital heart abnormalities [10]. Glaucomatous nerve damage, average axial length, shallow anterior chamber, and peripheral iris synechiae were inconsistent findings in these patients [10]. A brother and a sister from a Saudi Arabian family reported by Khan et al. [15] with a mutation in the ADAMTS17 gene showed high myopia and microspherophakia, but narrow angles in the sister only. Although both had short stature, none had increased IOP, brachydactyly, joint stiffness, or non-ocular congenital abnormalities [15]. Radner et al. [18] recently reported four Tunisian patients with autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis (ARCI) harboring a homozygous deletion of 100.96 kb that encompasses the first three exons of ADAMTS17, including the entire sequence of a non-coding RNA gene FLJ42289 (gene ID 388182) and exon 13 of the ARCI gene CERS3 (gene ID 204219, OMIM 615276). In addition to ichthyosis, these patients also had short stature and microspherophakia [18]. Of the four patients reported by Radner et al. [18], two patients had brachydactyly and joint stiffness, one patient did not have either brachydactyly or joint stiffness, and one patient was similar to our patient and showed only brachydacyly. Further, glaucoma, cataract, and myopia were inconsistent findings in these patients [18]. These observations suggest that all patients with ADAMTS17 mutations described to date showed a consistent finding of microspheropkaia and short stature, but other clinical features such as brachydactyly, joint stiffness, glaucoma, cataract, and heart problems were inconsistent findings [10,15,18]. Therefore, the distinction between WMS and WMS-like syndrome based on the absence of brachydactyly and joint stiffness in the latter is not appropriate. We suggest that all patients with mutations in the ADAMTS10, ADAMTS17, LTBP2, and FBN1 genes should be classified as WMS as long as they show a consistent finding of microspherophakia and short stature.

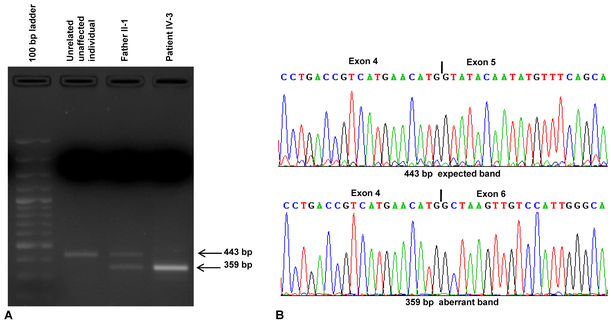

Mutations affecting the 5′ donor splice site have been described in several human genetic disorders. These mutations can result in several types of abnormal mRNAs, involving exon skipping, a combination of exon skipping, and the use of cryptic sites or the inclusion of intronic sequences in mature mRNAs [19]. RT–PCR analysis of total RNA isolated from peripheral blood samples from the patient and her father showed the presence of an expected size band of 443 bp and an aberrant band of 359 bp in the father and the aberrant band only in the patient (Figure 2A). DNA sequence analysis of these bands showed that the aberrant band resulted due to the skipping of the entire exon 5 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Reverse transcription (RT)–PCR analysis and Sanger sequencing to determine the effect of the mutation on splicing. A: Agarose gel electrophoresis of RT–PCR products. Note, the patient has a 359-bp band, whereas the father has two bands of 443 bp and 359 bp. B: Parts of the sequencing chromatograms of the 443- and 359-bp bands. Note that exon 5 is skipped in the 359-bp band (mutant allele).

The ADAMTS17 gene consists of 22 exons and codes for a protein of 1,095 amino acids (longer isoform a). The ADAMTS17 protein contains the following domains, Pep M12B propep (amino acids 36–180), two reprolysin repeats (amino acids 233–314 and 349–449), TSP1 (amino acids 547–597), ADAM spacer1 (amino acids 713–783), three TSP1 repeats (amino acids 868–896, 927–969, and 978–1028), and PLAC (amino acids 1048–1081). It also codes for a 502-amino-acid-long protein (shorter isoform b). Both isoforms are highly expressed in the lung, brain, whole eye, and retina [20]. Using immunohistochemistry of the eye sections from E14.5 mouse embryos, Morales et al. [10] showed diffuse expression of ADAMTS17 within the area of a future ciliary body. ADAMTS17 is a member of the secreted metalloproteinase family of proteins that are believed to bind to the extracellular matrix (ECM) via C-terminal TSP1 domains (repeats) [10,18]. Further, TSP1 domains have a role in activating transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta), a growth factor, which is sequestered and stored in the ECM. Interestingly, fibrillin-1, a constituent of the ECM, interacts with LTBP2 [21] and ADAMTS10 [22]. Sanger sequencing of the RT–PCR product from patient IV:3 showed the deletion of the entire exon 5, resulting in a predicted 1,067-amino-acid-long protein, due to the deletion of 28 amino acids from positions 264 to 291 in the reprolysin domain. The mutant ADAMTS17 protein may disrupt the organization of the ECM and thus its ability to sequester and store TGF-beta, resulting in WMS in the patient reported in this study.

In conclusion, our study provides evidence that the mutation in the WMS-like syndrome gene ADAMTS17 also causes WMS. With the mutation reported in this study, the total number of mutations in the human ADAMTS17 gene is six (Table 3).

Table 3. Known mutations in the human ADAMTS17 gene.

| Sl. # | Mutation | Exon/ Intron | Nature of the mutation | State of zygosity | Ethnic origin of the family | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

c.2458_2459insG

(p.E820Gfs*23) |

Exon 18 |

Frameshift |

Homozygous |

Saudi Arabian |

[10] |

| 2 |

c.1721+1G>A |

Intron 12 |

Splice site |

Homozygous |

Saudi Arabian |

[10] |

| 3 |

c.760C>T

(p.Q254*) |

Exon 4 |

Nonsense |

Homozygous |

Saudi Arabian |

[10] |

| 4 |

c.652delG

(p.Asp218Thrfs*41) |

Exon 4 |

Frameshift |

Homozygous |

Saudi Arabian |

[15] |

| 5 |

106.96 Kb Deletion |

Exon 1–3 |

Deletion |

Homozygous |

Tunisian |

[18] |

| 6 | c.873+1G>T | Intron 5 | Splice site | Homozygous | Indian | Present study |

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the patient and her family for their participation in this study. This work was funded by a grant (BT/PR11609/BRB/10/668/2008) from the Department of Biotechnology (Government of India), New Delhi.

References

- 1.Wright KW, Chrousos GA. Weill-Marchesani syndrome with bilateral angle-closure glaucoma. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1985;22:129–32. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19850701-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chu BS. Weill-Marchesani syndrome and secondary glaucoma associated with ectopia lentis. Clin Exp Optom. 2006;89:95–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2006.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rennert O-M. The Marchesani syndrome: a brief review. Am J Dis Child. 1969;117:703–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1969.02100030705016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herrera J, Morales M. Weill-Marchesani syndrome. Rev Chil Pediatr. 1986;57:571–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giordano N, Senesi M, Battisti E, Mattii G, Gennari C. Weill-Marchesani syndrome: report of an unusual case. Calcif Tissue Int. 1997;60:358–60. doi: 10.1007/s002239900243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kojuri J, Razeghinejad MR, Aslani A. Cardiac findings in Weill-Marchesani syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2007;143A:2062–4. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faivre L, Gorlin RJ, Wirtz MK, Godfrey M, Dagoneau N, Samples JR, Le-Merrer M, Collod-Beroud G, Boileau C, Munnich A. Inframe fibrillin-1 gene deletion in autosomal dominant Weill-Marchesani syndrome. J Med Genet. 2003;40:34–6. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dagoneau N, Benoist-Lasselin C, Huber C, Faivre L, Megarbane A, Alswaid A, Dollfus H, Alembik Y, Munnich A, Legeai-Mallet L. ADAMTS10 mutations in autosomal recessive Weill-Marchesani syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:801–6. doi: 10.1086/425231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haji-Seyed-Javadi R, Jelodari-Mamaghani S, Paylakhi SH, Yazdani S, Nilforushan N, Fan J-B, Klotzle B, Mahmoudi MJ, Ebrahimian MJ, Chelich N, Taghiabadi E, Kamyab K, Boileau C, Paisan-Ruiz C, Ronaghi M, Elahi E. LTBP2 mutations cause Weill-Marchesani and Weill-Marchesani-like syndrome and affect disruptions in the extracellular matrix. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:1182–7. doi: 10.1002/humu.22105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morales J, Al-Sharif L, Khalil DS, Shinwari JM, Bavi P, Al-Mahrouqi RA, Al-Rajhi A, Alkuraya FS, Meyer BF, Al-Tassan N. Homozygous mutations in ADAMTS10 and ADAMTS17 cause lenticular myopia, ectopia lentis, glaucoma, spherophakia, and short stature. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:558–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ali M, McKibbin M, Booth A, Parry DA, Jain P, Riazuddin SA, Hejtmancik JF, Khan SN, Firasat S, Shires M, Gilmour DF, Towns K, Murphy AL, Azmanov D, Tournev I, Cherninkova S, Jafri H, Raashid Y, Toomes C, Craig J, Mackey DA, Kalaydjieva L, Riazuddin S, Inglehearn CF. Null mutations in LTBP2 cause primary congenital glaucoma. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:664–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narooie-Nejad M, Paylakhi SH, Shojaee S, Fazlali Z, Kanavi MR, Nilforushan N, Yazdani S, Babrzadeh F, Suri F, Ronaghi M, Elahi E, Paisan-Ruiz C. Loss of function mutations in the gene encoding latent transforming growth factor beta binding protein 2, LTBP2, cause primary congenital glaucoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3969–77. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar A, Duvvari MR, Prabhakaran VC, Shetty JS, Murthy GJ, Blanton SH. A homozygous mutation in LTBP2 causes isolated microspherophakia. Hum Genet. 2010;128:365–71. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0858-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Désir J, Sznajer Y, Depasse F, Roulez F, Schrooyen M, Meire F, Abramowicz M. LTBP2 null mutations in an autosomal recessive ocular syndrome with megalocornea, spherophakia, and secondary glaucoma. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:761–7. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan AO, Mohammed A. Aldahmesh, Al-Ghadeer H, Jawaher Y, Mohamed, Alkuraya FS. Familial spherophakia with short stature caused by a novel homozygous ADAMTS17 mutation. Ophthalmic Genet. 2012;33:235–9. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2012.666708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farias FH, Johnson GS, Taylor JF, Giuliano E, Katz ML, Sanders DN, Schnabel RD, McKay SD, Khan S, Gharahkhani P, O'Leary CA, Pettitt L, Forman OP, Boursnell M, McLaughlin B, Ahonen S, Lohi H, Hernandez-Merino E, Gould DJ, Sargan DR, Mellersh C. An ADAMTS17 splice donor site mutation in dogs with primary lens luxation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:4716–21. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-5142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gould D, Pettitt L, McLaughlin B, Holmes N, Forman O, Thomas A, Ahonen S, Lohi H, O'Leary C, Sargan D, Mellersh C. ADAMTS17 mutation associated with primary lens luxation is widespread among breeds. Vet Ophthalmol. 2011;14:378–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-5224.2011.00892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radner FPW, Marrakchi S, Kirchmeier P, Kim G-J, Ribierre F, Kamoun B, Abid L, Leipoldt M, Turki H, Schempp W, Heilig R, Lathrop M, Fischer J. Mutations in CERS3 cause autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis in humans. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krawczak M, Reiss J, Cooper DN. The mutational spectrum of single base-pair substitutions in mRNA splice junctions of human genes: causes and consequences. Hum Genet. 1992;90:41–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00210743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kutz WE, Wang LW, Dagoneau N, Odrcic KJ, Cormier-Daire V, Traboulsi EI, Apte SS. Functional analysis of an ADAMTS10 signal peptide mutation in Weill-Marchesani syndrome demonstrates a long-range effect on secretion of the full-length enzyme. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:1425–34. doi: 10.1002/humu.20797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirani R, Hanssen E, Gibson MA. LTBP-2 specifically interacts with the N-terminal region of fibrillin-1 and competes with LTBP-1 for binding to this microfibrillar protein. Matrix Biol. 2007;26:213–23. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kutz WE, Wang LW, Bader HL, Majors AK, Iwata K, Traboulsi EI, Sakai LY, Keene DR, Apte SS. ADAMTS10 protein interacts with fibrillin-1 and promotes its deposition in extracellular matrix of cultured fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:17156–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.231571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]