Abstract

The use of helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS) for the transportation and treatment of trauma patients, while commonplace in most developed nations, remains controversial. The purported beneficial effects of HEMS compared to ground emergency medical services is likely to be some combination of speed, crew expertise, and the fact that HEMS is part of an organized trauma system. When the HEMS literature is assessed as a whole, considerable heterogeneity of effects and study methodologies preclude an accurate estimate of composite effect. However, when the outcome of mortality is studied using advanced multivariable regression techniques to control for multiple known confounders, an improved odds of survival has been repeatedly demonstrated. Future HEMS research must rely on robust observational study designs and assessments of a variety of patient outcomes. Questions about the role of speed, distance, and other potentially beneficial elements of HEMS remain.

The use of helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS) for the transportation and treatment of trauma patients is commonplace in most developed nations. Current research has questioned which traumatically injured patients derive the greatest benefit from the utilization of this limited and resource-intensive modality. In the previous issue of Critical Care, Andruszkow and colleagues [1] report a retrospective cohort including over 13,000 patients with traumatic injuries from a trauma registry maintained by the German Society for Trauma Surgery.

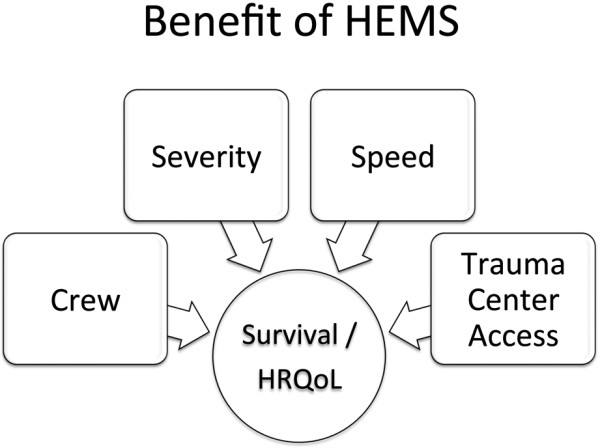

HEMS are capable of transporting patients with serious injury over greater distances significantly faster than ground emergency medical services (GEMS), and the speed benefit is more pronounced as the distance from a trauma center increases. HEMS crews are typically staffed by experienced providers and exist as an integral part of regional trauma systems. Thus, any beneficial effect of HEMS compared to GEMS is likely to be some combination of speed, crew expertise, and the fact that HEMS, as part of an organized trauma system, may afford seriously injured patients timely access to trauma centers [2,3] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Determinants of improved outcomes associated with helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS). HrQoL, health-related quality-of-life.

The question of which elements of HEMS are most beneficial for patients has not been fully answered, and the present study by Andruszkow and colleagues attempts to evaluate features of HEMS that may provide benefits for patients with major trauma. Crew expertise is likely to be an important contributing factor for improved survival in HEMS patients. HEMS in Germany and Europe is exclusively physician-staffed, unlike many HEMS systems in the US. In the present study, HEMS patients were statistically significantly more likely to be intubated, have a chest thoracostomy tube placed, receive sedation, or be treated with vasopressors [1]. HEMS patients were more frequently admitted to Level I trauma centers compared to GEMS patients even though a subgroup analysis demonstrated improved survival for HEMS patients independently of Level I admission status. Indeed, the accurate identification and triage of patients most likely to benefit from HEMS remains an elusive goal. Even when staffed by well-trained physicians, the accuracy of suspected diagnoses during resuscitation was problematic; future studies are required to accurately predict which groups of patients are most likely to benefit from HEMS.

To date, most HEMS comparative effectiveness studies have dealt with the outcome of survival, and less is known about posttraumatic outcomes and clinical course. Duration of ventilation, ICU length of stay, and overall hospital length of stay were significantly increased for HEMS patients in the present study. Future HEMS outcomes research must consider assessments for additional dimensions, such as health-related quality of life, rather than the traditionally studied endpoints of morbidity and mortality [4].

When the HEMS literature is assessed as a whole, considerable heterogeneity of effects and study methodologies preclude an accurate estimate of composite effect [3]. In the present study, a multivariable regression analysis found an improved odds of survival for HEMS compared to GEMS patients when 11 confounding variables were included in the model. Indeed, when the outcome of mortality is studied using advanced multivariable regression techniques to control for multiple known confounders, an improved odds of survival has been repeatedly demonstrated (Table 1) [1,5-9]. The use of advanced methods, such as propensity scores and instrumental variables, should be considered for future HEMS studies to minimize biased effect estimates [3,10].

Table 1.

Summary of studies using multivariate logistic regression to compare HEMS versus GEMS

| Study | Number of patients | Odds ratio for survival favoring HEMS | 95% confidence interval | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas et al. 2002 [5] | HEMS: 2,292 GEMS: 14,407 |

1.32 | 1.03-1.71 | Blunt trauma patients only |

| Brown et al. 2010 [6] | HEMS: 41,987 GEMS: 216,400 |

1.22 | 1.18-1.27 | Standard multivariable regression |

| Stewart et al. 2011 [7] | HEMS: 2,739 GEMS: 6,473 |

1.49 | 1.19-1.89 | Cox proportional hazards regression, including a propensity score as a confounding variable |

| Sullivant et al. 2011 [8] | HEMS: 10,049 GEMS: 46,695 |

1.64 | 1.45-1.87 | Standard multivariable regression |

| Galvagno et al. 2012 [9] | HEMS: 47,637 GEMS: 111,874 |

1.16 | 1.14-1.17 | Results for patients taken to Level I centers only; propensity score matched regression analysis |

| Andruszkow et al. 2013 [1] | HEMS: 4,989 GEMS: 8,231 |

1.33 | 1.16-1.57 | Standard multivariable regression |

GEMS, ground emergency medical services; HEMS, helicopter emergency medical services.

The trauma and injury severity score (TRISS) and Revised Injury Severity Classification (RISC) were used to compare mortality between HEMS and GEMS. As the authors acknowledge, there are several limitations that must be considered when these methodologies are used to compare study groups. Although used in several previous HEMS studies, TRISS has been shown to have a high misclassification rate, particularly in patients with severe trauma [11]. Additionally, since TRISS probability of survival is compared to a historical cohort, survival probabilities may be incomparable due to advances in trauma care. The authors did not report M and W statistics for the TRISS-based analysis. Reporting of these statistics is important because the M statistic for non-US populations may be below the cutoff for non-standardized TRISS analyses, thereby rendering comparisons invalid [12]. The RISC, while a more contemporary and potentially more accurate system for comparing outcomes [13], did not reveal a statistically significant survival benefit for HEMS compared to GEMS.

Given the infeasibility of conducting a randomized controlled trial comparing HEMS versus GEMS, future studies to estimate treatment effects for trauma patients will need to rely on robust observational study designs. Questions about the role of speed, distance, and other potentially beneficial elements of HEMS remain. Improvements in statistical techniques and the continued development of large databases, with minimization of missing data, are warranted to advance the science of aeromedical critical care [14].

Abbreviations

GEMS: ground emergency medical services; HEMS: helicopter emergency medical services; RISC: Revised Injury Severity Classification; TRISS: Trauma and Injury Severity Score.

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

See related research by Andruszkow et al., http://ccforum.com/content/17/3/R124

References

- Andruszkow H, Lefering R, Frink M, Mommsen P, Zeckey C, Rahe K, Krettek C, Hildebrand F. Survival benefit of helicopter emergency medical services compared to ground emergency medical services in traumatized patients. Crit Care. 2013;17:R124. doi: 10.1186/cc12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SH, Biddinger PD. Helicopter trauma transport: an overview of recent outcomes and triage literature. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2003;17:153–158. doi: 10.1097/00001503-200304000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvagno SM Jr, Thomas S, Stephens C, Haut ER, Hirshon JM, Floccare D, Pronovost P. Helicopter emergency medical services for adults with major trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;17:CD009228. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009228.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvagno S. Assessing health-realted qualtiy of life with the EQ-5D: is this the best instrument to assess trauma outcomes? Air Med J. 2011;17:258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.amj.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SH, Cheema F, Wedel SK, Thomson D. Trauma helicopter emergency medical services transport: annotated review of selected outcomes-related literature. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2002;17:359–371. doi: 10.1080/10903120290938508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JB, Stassen NA, Bankey PE, Sangosanya AT, Cheng JD, Gestring ML. Helicopters and the civilian trauma system: national utilization patterns demonstrate improved outcomes after traumatic injury. J Trauma. 2010;17:1030–1034. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f6f450. discussion 4-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart K, Cowan L, Thompson D, Sacra J, Albrecht R. Association of direct helicopter versus ground transport and in-hospital mortality in trauma patients: A propensity score analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;17:1208–1216. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivent E, Faul M, Wald M. Reduced mortality in injured adults transported by helicopter emergency medical services. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2011;17:295–302. doi: 10.3109/10903127.2011.569849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvagno SM Jr, Haut ER, Zafar SN, Millin MG, Efron DT, Koenig GJ Jr, Baker SP, Bowman SM, Pronovost PJ, Haider AH. Association between helicopter and ground emergency medical services and survival for adults with major trauma. JAMA. 2012;17:1602–1610. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunsch H, Linde-Zwirble W, Angus D. Methods to adjust for bias and confounding in critical care health services research involving observational data. J Crit Care. 2006;17:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetriades D, Chan L, Velmanos G, Sava J, Preston C, Gruzinski G. TRISS methodology: an inappropriate tool for comparing outcomes between trauma centers. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;17:250–254. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(01)00993-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluter PJ, Nathens A, Neal ML, Goble S, Cameron CM, Davey TM, McClure RJ. Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS) coefficients 2009 revision. J Trauma. 2010;17:761–770. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181d3223b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brilej D, Vlaovic M, Kamadina R. Improved prediction from revised injury severity classification (RISC) over trauma and injury severity score (TRISS) in an independent evaluation of major trauma patients. J Int Med Res. 2010;17:1530–1538. doi: 10.1177/147323001003800437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent J. We should abandon randomized controlled trials in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2010;17(Suppl):S534–S538. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f208ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]