Abstract

Aims

Natriuretic peptide-guided (NP-guided) treatment of heart failure has been tested against standard clinically guided care in multiple studies, but findings have been limited by study size. We sought to perform an individual patient data meta-analysis to evaluate the effect of NP-guided treatment of heart failure on all-cause mortality.

Methods and results

Eligible randomized clinical trials were identified from searches of Medline and EMBASE databases and the Cochrane Clinical Trials Register. The primary pre-specified outcome, all-cause mortality was tested using a Cox proportional hazards regression model that included study of origin, age (<75 or ≥75 years), and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF, ≤45 or >45%) as covariates. Secondary endpoints included heart failure or cardiovascular hospitalization. Of 11 eligible studies, 9 provided individual patient data and 2 aggregate data. For the primary endpoint individual data from 2000 patients were included, 994 randomized to clinically guided care and 1006 to NP-guided care. All-cause mortality was significantly reduced by NP-guided treatment [hazard ratio = 0.62 (0.45–0.86); P = 0.004] with no heterogeneity between studies or interaction with LVEF. The survival benefit from NP-guided therapy was seen in younger (<75 years) patients [0.62 (0.45–0.85); P = 0.004] but not older (≥75 years) patients [0.98 (0.75–1.27); P = 0.96]. Hospitalization due to heart failure [0.80 (0.67–0.94); P = 0.009] or cardiovascular disease [0.82 (0.67–0.99); P = 0.048] was significantly lower in NP-guided patients with no heterogeneity between studies and no interaction with age or LVEF.

Conclusion

Natriuretic peptide-guided treatment of heart failure reduces all-cause mortality in patients aged <75 years and overall reduces heart failure and cardiovascular hospitalization.

Keywords: Natriuretic peptides, B-type Natriuretic peptide, Heart failure

See page 1507 for the editorial comment on this article (doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu134)

Introduction

How best to guide the complex pharmacotherapy of chronic heart failure is in dispute. Whereas some medications, namely angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), angiotensin receptor antagonists, certain beta-blockers (BB), and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) have been shown to improve survival in patients with chronic heart failure and a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF),1 the optimal dosage of these agents in individuals is guided largely by subjective indices, namely the clinician's assessment of symptoms, bedside signs and tolerability. Consequently, evidence-based target doses of these proven medications are rarely achieved outside the clinical trial setting, even in eligible patients.2 Despite lack of trial evidence for longevity benefit, loop and/or thiazide-like diuretics are seen as central to the treatment of almost all patients with chronic heart failure. Here again, optimal or target doses are dictated largely by clinician interpretation of the patient's symptoms and signs. It would obviously be useful if pharmacotherapy could be directed not only by subjective bedside indices but also by an objective index of circulatory status. In this regard, it has been proposed that circulating levels of the B-type cardiac natriuretic peptides (BNP and NT-proBNP), which are released from the heart in proportion to stretch of the cardiac chambers, might provide such an objective guide. This proposition is reinforced first, by evidence that circulating levels of these peptides and change in their levels over time provide a robust prognostic index in chronic heart failure3 and second, each of the drug groups which demonstrably increase longevity, as well as loop diuretics, reduce their levels in the circulation.4

Several studies have addressed the hypothesis, first proposed in the late 1990s, that pharmacotherapy guided by BNP or NT-proBNP levels (NP-guided treatment) would improve clinical outcomes.5–15 While some of these studies demonstrated a reduction in combined clinical events, no single study was adequately powered to test the effect of this strategy on all-cause mortality—the ultimate clinically relevant endpoint.

In viewing results from published studies, the European Society of Cardiology,1 the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE),16 the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association,17 the National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry,18 and the National Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand19 opined that the evidence is insufficient to support routine NP-guided treatment over conventional care.

Previous literature-based meta-analyses using aggregate data have suggested that NP-guided treatment may be associated with a 20–30% reduction in all-cause mortality.20–22 Such meta-analyses, however, can have important limitations relating to potential heterogeneity of patient characteristics and outcome definitions. In contrast, meta-analyses based on individual patient data allow more rigorous testing with the incorporation of standard outcome definitions and provide the opportunity to consider important patient characteristics that could influence outcomes or mitigate/moderate the effects of treatment interventions on outcomes.23 Accordingly, we performed an individual patient data meta-analysis, which includes data from studies published subsequent to two of the earlier aggregate data meta-analyses7,12,13 to test the hypothesis that compared with conventional clinically guided management, NP-guided therapy results in a reduction in all-cause mortality.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched MEDLINE and EMBASE for studies published between 1 January 2000 and 29 February 2012. The search query included keywords and corresponding MeSH terms for natriuretic peptide, brain natriuretic peptide, B-type natriuretic peptide, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, heart failure, treatment, and therapy. Similar searches were made of the Cochrane Controlled Clinical Trials Register database and of the clinicaltrials.gov website. Only randomized controlled clinical trials reporting all-cause mortality and comparing B-type natriuretic peptide-guided treatment of heart failure with clinically guided treatment were included. The exception was one study which, while not providing all-cause mortality data, was randomized and provided robust secondary endpoint results.13 The search strategy was similar to that described in publications reporting meta-analyses based on aggregate data.20–22

Data extraction

Individual patient data from eligible studies were entered into the meta-analysis database and included patient age, gender, baseline BNP or NT-proBNP level (pg/mL), baseline creatinine (µmol/L), baseline LVEF (%), treatment assignment (NP-guided or clinically guided), and randomization date. Outcome data included all-cause mortality and date of all-cause death or last follow-up. First hospitalization for any cause, for heart failure or for any cardiovascular disease, along with the date of hospitalization was also included. Only events occurring during application of the treatment strategy were included in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

The pre-specified primary outcome was all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included death or any hospitalization, cardiovascular hospitalization, heart-failure hospitalization, and all-cause hospitalization.

We analysed all outcomes as time-to-event data using Cox proportional hazards regression models. The time-to-event data include follow-up as reported in the publications from each study and therefore does not extend beyond the period of the guided treatment in each study. Age (<75, ≥75 years), LVEF (≤45%, >45%) at enrolment, study (as a fixed effect), treatment allocation (NP-guided vs. clinically guided), treatment*age, treatment* LVEF, and treatment*study were included as terms in the regression models. The interaction terms (treatment*age and treatment* LVEF) were used to test the consistency of treatment effects across age and LVEF groups. We used the treatment*study interaction effect to test the heterogeneity of treatment effects across studies. The impact of study geographical location on treatment strategy and medication changes was tested by adding geographical location (Europe, USA, or New Zealand) as a covariate within the Cox model.

Hazard ratios comparing outcomes in the NP-guided and clinically guided treatment groups were summarized for all studies pooled and for each study individually with 95% confidence intervals. Kaplan–Meier curves were used to portray the comparative time to event results.

We compared changes in medications, plasma natriuretic peptide, and creatinine levels between groups using general linear models. These models included age, LVEF, study, and treatment as factors.

We performed all individual patient analyses with SPSS (v19) software. Analyses using aggregated measures and production of the associated forest plots were undertaken with RevMan5.

Results

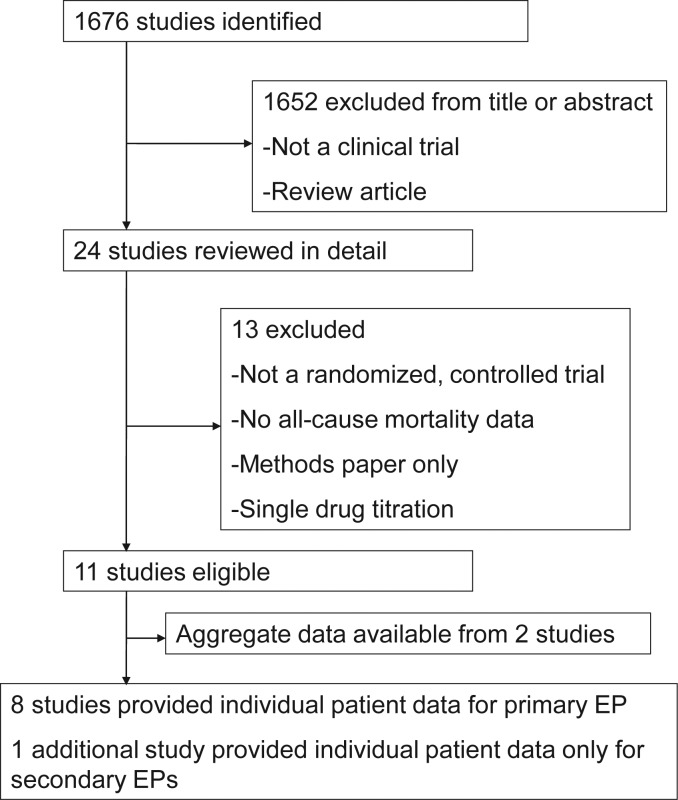

We identified 11 eligible studies (Figure 1, Table 1),5–15 8 of which provided individual patient data for all-cause mortality (n = 2000).5–12 Based on excellent concordance between data provided for the meta-analysis and the original published reports, the quality of data was judged to be high. All studies reported endpoints on an intention-to-treat basis. For two studies, data from only two treatment groups (NP-guided and clinically guided) who received intensive clinical follow-up were considered for the analysis, whereas data from the third (‘usual care’) groups were not included.7,10 For two studies, complete individual patient data were not available but aggregate data on overall mortality were obtained from published reports (n = 2431 when aggregate data included).14,15 Finally, the ProBNP Outpatient Tailored Chronic Heart Failure Therapy (PROTECT) trial, while not providing overall mortality data, gave robust secondary endpoint results (n = 2151 for individual patients with data for secondary end-points).13

Figure 1.

Flow diagram outlining search strategy, study selection, and reasons for exclusion.

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Peptide target | Clinical target | Primary endpoint | Study period | Duration | Follow-up | Treatment algorithm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies providing individual patient data | |||||||

| Christchurch Pilot5 | NT-proBNP <1700 pg/mL | HF score | Mortality + CV hospitalization + out-patient HF | 1997–99 | 9.5 months | 2-weekly until target met, then 3-monthly | Stepwise increase in ACEi, diuretic, AA, additional vasodilator |

| TIME-CHF6 | NT-proBNP <400a; NT-proBNP <800b | NYHA ≤II | Survival free of hospitalization | 2001–06 | 18 months | 1, 3, 6, 12, 18 months | Investigator determined stepwise increase in therapy via algorithm |

| Vienna7 | NT-proBNP <2200 pg/mL | Clinical assessment | Survival without HF hospitalization | 2003–04 | ≥12 months | 2-weekly to meet target, 1, 3, 6, and 12 months | Investigator determined increase in therapy |

| PRIMA8 | Individual: lowest NT-proBNP at discharge or at 2-week follow-up | Clinical assessment | Days alive and out of hospital | 2004–07 | ≥12 months | 2 and 4 weeks, then 3 monthly | Investigator determined increase in guideline based therapy |

| SIGNAL-HF9 | NT-proBNP reduction >50% from baseline | Clinical assessment | Composite of days alive, days out of hospital and symptom score | 2006–09 | 9 months | 1, 3, 6, and 9 months | Investigator determined stepwise increase in guideline-based therapy |

| BATTLESCARRED10 | NT-proBNP <1300 pg/mL | HF score | All-cause mortality | 2001–06 | 24 months | 2-weekly until target met, then 3-monthly | Stepwise increase in ACEi, BB, diuretic, AA, additional vasodilator |

| STARBRITE11 | Individual BNP at discharge | Congestion score | Days alive and out of hospital | 2003–05 | >3 months | 10, 30, 60, 90, 120 days and additional visits as required | Investigator determined increase in therapy |

| UPSTEP12 | BNP <150 ng/La; BNP <300 ng/Lb | Clinical assessment | Composite of all-cause mortality, hospitalization, or HF worsening | 2006–09 | ≥12 months | Weeks 2, 6, 10, 16, 24, 36, 48, then 6-monthly | Investigator determined stepwise increase in therapy via algorithm |

| PROTECTc13 | NT-proBNP <1000 pg/mL | Clinical assessment | Total cardiovascular events | 2006–10 | ≥6 months | As required to achieve target then 3-monthly | Investigator determined increase in guideline based therapy |

| Studies providing aggregate data | |||||||

| STARS-BNP14 | BNP < 100 pg/mL | Clinical assessment | HF mortality + HF hospitalization | 2001–05 | 15 months | Months 1, 2, 3 and then 3-monthly | Investigator determined increase in guideline based therapy |

| Anguita et al.15 | BNP < 100 pg/mL | Clinical Score | Survival free of HF hospitalization | 16 months | 1, 2, 3, 6, 12, and 18 months | Investigator determined increase in guideline-based therapy | |

HF, heart failure; CV, cardiovascular; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; BB, beta-blocker; AA, aldosterone antagonist; NYHA, New York Heart Association functional class.

aPatients aged <75 years.

bPatients aged ≥75 years.

cThe PROTECT study provided only secondary endpoint data.

Study characteristics

There were differences between studies regarding design relating to duration, target plasma level for the B-type natriuretic peptides, and treatment algorithm (Table 1), but all studies compared a treatment strategy guided by BNP/NT-proBNP with clinically guided treatment. The majority of studies used a single target BNP or NT-proBNP level for the NP-guided group. In two studies, age-stratified NT-proBNP targets were utilized.6,12 In one study, a target of ≥50% reduction in NT-proBNP was used9 and in a further two studies an individualized BNP or NT-proBNP target was utilized based on levels at discharge from hospital.8,11 Treatment algorithms differed slightly between studies, but were all based upon stepwise up-titration of guideline-recommended drug therapies.

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics for the meta-analysis cohort and for individual studies are summarized in Table 2. The average age of participants was 72 years and two-thirds were male. The majority of subjects had LV systolic dysfunction and only 10% had an LVEF >45%.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| Number (BNP-guided /clinical) | Age (years) (mean ± SD) (% >75 years) | Gender (M/F) | LVEF (%) (mean ± SD) (% ≤0.45) | Creatinine (µmol/L) (mean ± SD) | NT-proBNP (pg/mL) [median (IQR)] | BNP (pg/mL) (mean ± SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual patient data | |||||||

| Christchurch Pilot5 | 33/36 | 70 ± 10 (35) | 53/16 | 27 ± 8 (100) | 100 ± 30 | 1980 (1077–2806) | – |

| TIME-CHF6 | 251/248 | 76 ± 8 (58) | 327/172 | 30 ± 8 (100) | 117 ± 38 | 4194 (2270–7414) | – |

| Vienna7 | 92/96 | 71 ± 12 (47) | 147/76 | 29 ± 9 (94) | 125 ± 49 | 2280 (1255–5192) | – |

| PRIMA8 | 174/171 | 72 ± 12 (48) | 199/146 | 36 ± 14 (73) | 138 ± 58 | 2949 (1318–5445) | – |

| SIGNAL-HF9 | 127/125 | 78 ± 7 (73) | 180/72 | 32 ± 8 (98) | 102 ± 38 | 2362 (1372–4039) | – |

| BATTLESCARRED10 | 121/121 | 74 ± 9 (57) | 157/85 | 39 ± 15 (63) | 119 ± 45 | 2001 (1235–2974) | – |

| STARBRITE11 | 68/69 | 60 ± 16 (18) | 95/42 | 20 ± 6 (100)a | 131 ± 57 | – | 134 (54–346) |

| UPSTEP12 | 140/128 | 71 ± 10 (39) | 196/72 | – | 108 ± 34 | – | 608 (356–947) |

| PROTECT13b | 75/76 | 63 ± 14 (25) | 127/24 | 27 ± 9 (100) | 130 ± 40 | 2118 (1121–3830) | – |

| TOTAL | 1081/1070 | 72 ± 11 (49) | 1459/692 | 31 ± 12 (91) | 120 ± 46 | 2697 (1425–5110) | 446 (208–821) |

| Aggregate data | |||||||

| STARS-BNP14 | 110/110 | 66 ± 5 | 127/93 | 31 ± 8 | 95 ± 40 | – | 352 ± 260c |

| Anguita et al.15 | 30/30 | 70 ± 10 | 41/19 | – | – | – | 136 ± 149 |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

aIndividual LVEF data dichotomized as <30 or 30–45%.

bThe PROTECT study provided only secondary endpoint data.

cIn the STARS-BNP study, plasma BNP levels available only in the BNP guided arm.

Primary endpoint

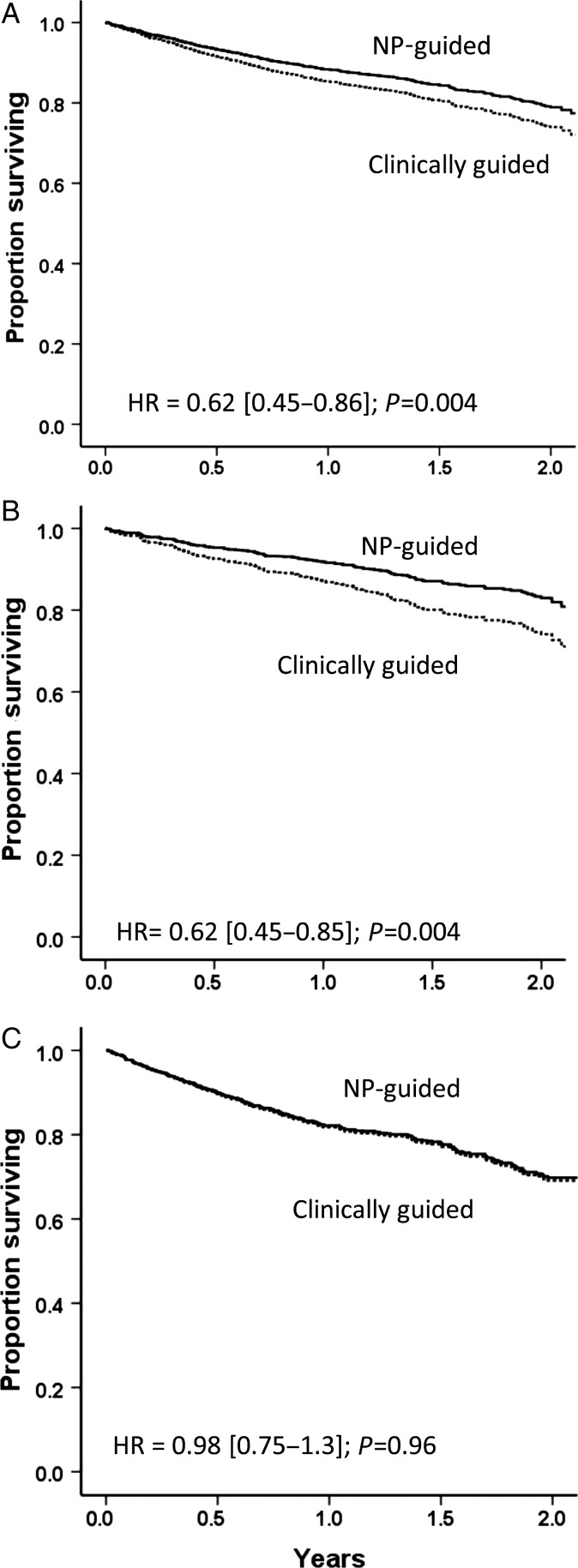

During active treatment, there were 207 deaths among patients assigned to clinically guided treatment compared with 172 deaths in the NP-guided group [HR = 0.62 (CI 0·45–0.86); P = 0.004, Figure 2]. There was no significant heterogeneity in the effect of NP-guided therapy on all-cause mortality between studies (P = 0.57, Cox interaction term). There was, however, a significant interaction between age and treatment efficacy (P = 0.028), with a survival benefit for NP-guided vs. clinical treatment in patients aged <75 years [HR = 0.62 (0.45–0.85); P = 0.004] but not in patients ≥75 years [HR = 0.98 (0.75–1.3); P = 0.96, Figure 2]. No interaction was evident for LVEF. There was no significant interaction between geographical location and treatment efficacy for the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality (P = 0.8 for interaction term) or any other endpoint (P ≥ 0.6 for all).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the primary endpoint, overall mortality: (A) total group, (B) below age 75 years (n = 982), (C) 75 years and above (n = 1018).

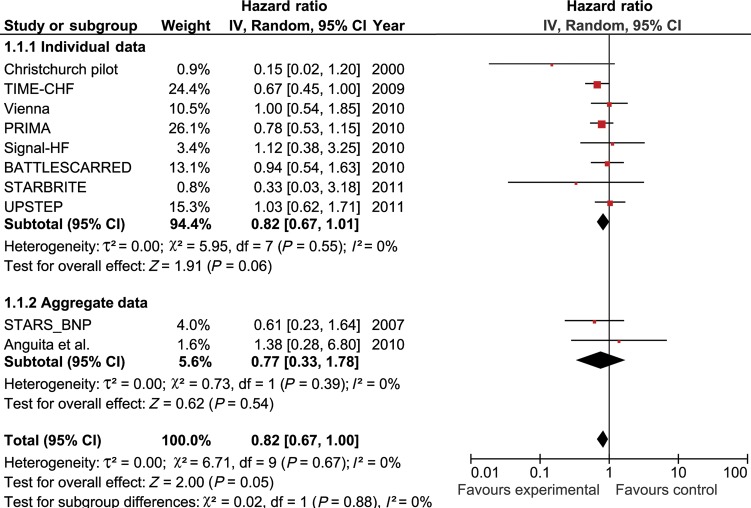

Combining the eight studies providing individual patient data with the two studies reporting aggregated data using a random effects model demonstrated a significant (P = 0.045) reduction in all-cause mortality with NP-guided therapy (unadjusted, Figure 3). There was no significant heterogeneity exhibited between studies.

Figure 3.

FOREST plot of the primary endpoint, overall mortality, showing unadjusted individual and mean hazards ratios with 95% confidence intervals for eight studies providing individual patient data and two studies providing aggregate data.

Secondary endpoints

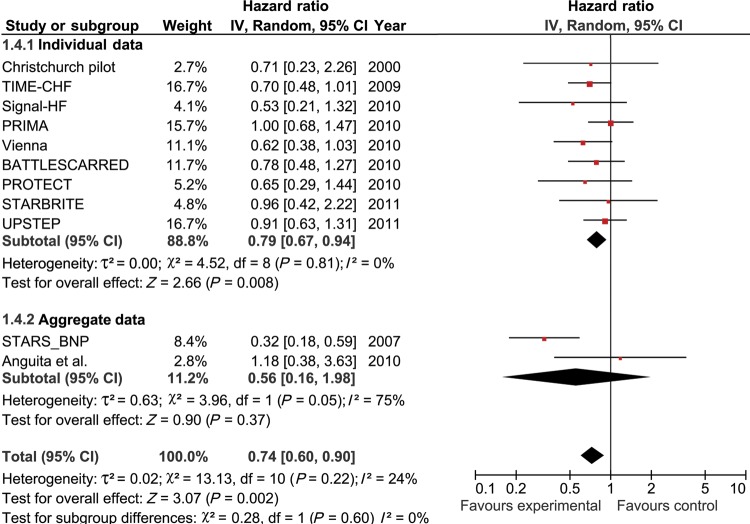

Heart failure hospitalizations were reduced in the NP-guided group, n = 247 compared with n = 294 in clinically guided patients [HR = 0.80 (0.67–0.94); P = 0.009] as were cardiovascular admissions [n = 430 in the NP-guided group compared with n = 448, HR = 0.82 (0.67–0.99); P = 0.048] with no heterogeneity between studies and no interaction with age or LVEF. When combined with aggregate data from two additional studies, a significant reduction in HF hospitalization was observed (unadjusted, Figure 4). All-cause hospitalization [HR = 0.94 (0.84–1.07); P = 0.38] was not reduced by NP-guided treatment (n = 555 NP-guided, n = 560 clinically guided); however, the combined endpoint of all-cause mortality or all-cause hospitalization was lower for NP-guided treatment (n = 587) compared with clinically guided therapy (n = 605) [HR = 0.84 (0.71–0.99); P = 0.037].

Figure 4.

FOREST plot of the secondary endpoint, heart failure hospitalization, showing unadjusted individual and mean hazards ratios with 95% confidence intervals for nine studies providing individual patient data and two studies providing aggregate data.

Effects on natriuretic peptide levels

Follow-up plasma NT proBNP levels were available in 1313 participants at the end of the study (NP-guided group 668, clinically guided group 645). Among these subjects, there was a similar fall in NT-proBNP levels in the former [35.0% (28.5–41.0)] and latter groups [31.5% (24.5–37.8); P = 0.44]. The fall in NT-proBNP was significantly (P < 0.001) greater for patients aged <75 years. There was, however, no interaction between age and treatment effect (P = 0.38), with comparable differences in the fall in NT-proBNP between treatment groups in the younger [NP-guided group 43.4% (34.8–50.9), clinical group 40.8% (31.2–49.0); P = 0.67] and older age groups [NP-guided group 26.4% (15.3–36.0), clinical 19.9% (8.8–29.7); P = 0.38].

Plasma creatinine levels, available in 1396 patients at the end of the study (713 patients in the NP-guided group and 683 in the clinical group), showed a tendency to rise similarly in both groups (+12.6 ± 1.9 µmol/L and +12.7 ± 1.9 µmol/L, respectively, P = 0.98).

Medication changes

The percentage of patients receiving medications recommended by heart failure guidelines was very high and similar to percentages reported in large randomized controlled trials performed during the same time period. Among NP-guided patients, ACEi/ARB, BB, and MRA were prescribed in 91, 78, and 29%, respectively, compared with 89, 73, and 29% in clinically guided patients. Loop diuretics were prescribed in 87% of patients in both treatment groups. Baseline doses of medications and the percent of patients receiving target doses as defined by guidelines were similar in both treatment groups (Table 3). By the time of last follow-up ACEi/ARB dosing had increased in the NP-guided group [+8.4% (3.4–13.5) enalapril equivalents] but changed little in the clinical group [−1.2% (−6.1–3.7)] (P = 0.007 for group comparison). There was a strong age interaction with change in ACEi/ARB drug doses which increased among younger patients (<75 years) in both treatment groups [+11.7% (5.3–18.0) in the NP-guided group and +4.3% (−2.3–10.8) in the clinical group, P < 0.01], whereas in older patients (≥75 years), ACEi/ARB doses increased in the NP-guided group by +5.2% [−1.8–12.2] but tended to fall in the clinical group −6.7% [−13.4–0.5], (P < 0.01), (P = 0.006 for age comparison).

Table 3.

Medications

| Baseline |

Study end |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (mean ± SEM) |

Percent of patients at target (%) |

Dose (mean ± SEM) |

Percent of patients at target (%) |

|||||

| Clinical | NP | Clinical | NP | Clinical | NP | Clinical | NP | |

| ACEi/ARBa | 61 ± 2 | 64 ± 2 | 32% | 36% | 60 ± 2 | 70 ± 3 | 34% | 41% |

| Beta-blockera | 32 ± 1 | 38 ± 1 | 11% | 14% | 39 ± 2 | 42 ± 2 | 19% | 19% |

| Spironolactone (mg) | 9.1 ± 0.6 | 9.5 ± 0.6 | 26% | 26% | 9.8 ± 0.6 | 11.1 ± 0.7 | 26% | 28% |

| Loop diuretic (mg) | 72 ± 3 | 66 ± 3 | – | – | 66 ± 5 | 67 ± 5 | – | – |

ACEi/ARB, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin type 1 receptor blocker; clinical, clinically guided treatment group; NP, natriuretic peptide guided group.

aACEi/ARB and beta-blocker doses are expressed as percent of target values as defined by guidelines (1) and reported as mean ± standard error of the mean for all subjects within each treatment group; percent at target, percentage of patients within each treatment group who were at 100% of target dose as defined by guidelines.

Doses of BB had increased to a similar extent in both treatment groups by the end of follow-up [+12.6% (8.7–16.5) metoprolol equivalents in the NP-guided group and +13.4% (9.6–17.3) in the clinical group]. There were, however, significantly greater increases in younger (<75 years) patients [+16.1% (11.2–21.0) in the NP-guided group, and +15.0% (9.9–20.0) in the clinical group] compared with older (≥75 years) patients [+9.1% (3.7–14.4) in NP-guided and +11.9% (6.6–17.1) in the clinical group −6.7% (−13.4–0.5)] (P = 0.037 for age comparison).

Beta-blocker doses as a percent of target were slightly higher at baseline in the NP-guided compared with clinical groups in the studies from Europe (43 vs. 35%, respectively, compared with 31 vs. 30% in the USA and 15 vs. 14% in New Zealand; P = 0.044 for interaction). Lower BB doses in the NZ studies were largely due to the pilot study,5 which commenced before BB therapy was endorsed in guidelines. There were no other significant interactions between geographical study location and medication doses at baseline or final follow-up.

Inclusion of change in ACEi/ARB dose, change in BB dose, and change in MRA dose demonstrated that increasing doses of each of these medications was significantly (P < 0.001 for each) associated with reduced all-cause mortality. When baseline medication doses and the change in medication doses during follow-up were included as co-variates in the Cox regression model, both the NP-guided treatment strategy and the age by treatment group interaction remained significant predictors of all-cause mortality [HR for overall effect = 0.64 (0.46–0.89); P = 0.008]. There was no significant interaction between treatment strategy and change in ACEi/ARB dose (P = 0.7), change in BB dose (P = 0.24), and change in MRA dose (P = 0.7), indicating that there was no differential effect of medications dependent on treatment strategy such that in both treatment groups an increase in medications was associated with improved outcomes.

There was a significant age effect on the change in loop diuretic dosing (furosemide equivalents) across the study with the dose increasing in younger patients [+13 mg (0.7–25) in the NP-guided group and +6.4 mg (−6.1–19.0) in clinical group] but not in the older patients [−0.6 mg (−13.9–12.8) and −7.1 mg (−20.1–5.9)], respectively; (P = 0.027 for age comparison).

Discussion

The hypothesis that circulating levels of the B-type natriuretic peptides, by providing an objective index of circulatory status in patients with chronic heart failure, should allow clinicians to more accurately target pharmacotherapy to the individual patient has intuitive appeal. Based on evidence from individual studies and aggregate data meta-analyses, however, advice to clinicians from specialty societies regarding the use of BNP-guided management remains cautious,1,16–19 with none proposing that the approach should be used as a routine. The results of the study reported here should, we believe, lead to reconsideration of these recommendations.

In our meta-analysis, we used individual patient data from studies included in and subsequent to those utilized in the earlier meta-analyses. There were 2000 patients randomized to NP-guided or clinically guided treatment among whom 379 deaths were recorded, 172 in those randomized to NP-guidance vs. 207 in the clinically guided group. There was no significant heterogeneity across the studies. Furthermore, no interaction with LVEF was observed although, since only 10% of patients included in this meta-analysis had a LVEF >45%, such an interaction may possibly have been seen had a substantial number of patients with heart failure and preserved left ventricular systolic function been included. We did, however, observe a significant interaction with age, the all-cause mortality benefit being seen in patients <75 years but not in those aged ≥75 years. One explanation for the lack of mortality benefit in the older cohort could be that increases in the dose of some drugs were less overall than in <75 year old patients. It is conceivable, based on results from the PROTECT study,13,24 that elderly patients will exhibit benefit with more gradual, careful up-titration of medications according to BNP/NT-proBNP levels than younger patients. The value of performing an individual patient data meta-analysis is highlighted by comparing the powerful effect estimate for the NP-guided strategy demonstrated in Figure 2A, where there is adjustment for key patient characteristics, with the more modest effect and nominal significance shown in Figure 3, based on unadjusted aggregate data.

The most obvious explanation for the superior mortality outcome with NP-guided therapy is that selected individual patients, based on plasma BNP/NT-proBNP levels, received appropriately higher doses of the ACEi and ARB groups of drugs. Although changes across the studies in doses of the other three groups of drugs (BB, MRA and loop diuretics) did not differ overall between the two treatment groups, it is conceivable that alterations in doses of these agents either upward or downward in individuals within the NP-guided group, as dictated by BNP/NT-proBNP levels, were more ‘appropriate’ than in clinically guided patients and thereby contributed to the superior mortality outcome.

Beyond considerations of total mortality, our meta-analysis showed that NP-guided treatment reduced substantially the readmission rate for heart failure and for cardiovascular disease. With regard heart failure, this observation has major financial implications since hospitalizations dominate the cost of managing this increasingly common disorder. In the USA, for example, hospitalizations account for the majority of the US$39 billion spent annually on heart failure care.25 Accordingly, widespread implementation of NP-guided therapy has the potential to reduce considerably the costs of heart failure care—as indeed was reported by Laramee et al.26 from studies utilizing serial measurements of natriuretic peptide levels by a specialist—except in patients aged >75 years. An added impetus to the implementation of NP-guided pharmacotherapy in the USA is likely given that hospitals with high risk-standardized readmission rates will be subjected to a Medicare reimbursement penalty as of 2013.27

Since any therapeutic plan has the potential to unexpectedly induce or exacerbate concomitant disorders, it is noteworthy that there was no increase in overall hospitalizations and no deterioration in renal function as gauged by serum creatinine levels, with NP-guided treatment. It seems unlikely, therefore, that unexpected harm results from the implementation of NP-guided treatment.

Some limitations in our study should be noted. There were differences in study design particularly regarding BNP/NT-proBNP targets, although these did not produce heterogeneity in key results as tested in this meta-analysis. With respect to application of the NP-guided strategy, use of a single, low target level of BNP or NT-proBNP may provide more opportunities to up-titrate therapy. Our meta-analysis, however, cannot provide firm advice on this matter. Individual patient data were not available from two published studies;14,15 however, it is unlikely that inclusion of individual data from these or other unpublished studies would have altered the overall findings of this meta-analysis. Individual data for adverse events were not available for analysis from any of the studies. However, published original reports of each individual study did not identify any significant difference in adverse events between study groups. In a subset of the current study cohort, as reported above, changes in renal function, as measured by plasma creatinine levels, did not differ between the two study groups.

To date, only NP-guided therapy has been widely tested in randomized controlled studies. However, a wide range of biomarkers reflecting different aspects of heart failure pathophysiology—including markers of renal dysfunction, fibrosis, myocardial necrosis, and inflammation—provide risk stratification that is incremental to NPs and could potentially play a role in guiding treatment.28–33 Further study is certainly needed to evaluate multi-marker strategies to guide HF therapy.

In summary, this robust individual patient meta-analysis indicates that for patients aged <75 years with chronic heart failure most of whom had impaired left ventricular systolic function, NP-guided treatment reduced all-cause mortality compared with clinically guided therapy. This strategy also reduces hospitalizations for heart failure and cardiovascular disorders, irrespective of age. Therefore, we propose that NP-guided treatment should be considered in such patients, although a well-powered, large scale, randomized, and blinded study which includes adequate numbers of heart failure patients with both reduced and preserved EF would provide reassurance in this regard.

Author contributions

On behalf of the meta-analysis group, R.W.T., M.G.N., and C.M.F. oversaw the search strategy, integration of the data into the meta-analysis database, and writing of the initial draft and final submitted manuscript. C.M.F. performed the statistical analyses.

All other authors contributed equally—overseeing the conduct and data collection of the original randomized controlled studies, agreeing on the original analysis plan, sorting, and extracting the data for inclusion in the meta-analysis, revising the draft of the article and reviewing the final submission.

Funding

None specific to the meta-analysis. Funding related to the original studies included in the meta-analysis is outlined in the attached appendix. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the Christchurch Heart Institute at the University of Otago, Christchurch.

Conflicts of interest: R.T.—grant support and honoraria from Roche Diagnostics and St Jude Medical. L. E.—consultancy fees from Roche Diagnostics. J.J.–grant support from Roche Diagnostics, BG Medicine, Critical Diagnostics, Brahms; Consultancy fees from Sphingotec, Critical Diagnostics. M.R.—Honoraria, travel grants and research grants from Roche Diagnostics and Alere. H.-P.B.L.—grant support from Roche Diagnostics. C.O'C.—institutional grant support from Roche Diagnostics. U.D.—consultancies and honoraria from Vitor Pharma. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

Mr Nick Davis assisted with data entry and analysis.

References

- 1.McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Bohm M, Dickstein K, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fonseca C, Gomez-Sanchez MA, Jaarsma T, Kober L, Lip GY, Maggioni AP, Parkhomenko A, Pieske BM, Popescu BA, Ronnevik PK, Rutten FH, Schwitter J, Seferovic P, Stepinska J, Trindade PT, Voors AA, Zannad F, Zeiher A, Bax JJ, Baumgartner H, Ceconi C, Dean V, Deaton C, Fagard R, Funck-Brentano C, Hasdai D, Hoes A, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, McDonagh T, Moulin C, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Vahanian A, Windecker S, McDonagh T, Sechtem U, Bonet LA, Avraamides P, Ben Lamin HA, Brignole M, Coca A, Cowburn P, Dargie H, Elliott P, Flachskampf FA, Guida GF, Hardman S, Iung B, Merkely B, Mueller C, Nanas JN, Nielsen OW, Orn S, Parissis JT, Ponikowski P. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1787–1847. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lenzen MJ, Boersma E, Scholte op Reimer WJM, Balk AHMM, Komajda M, Swedberg K, Follath F, Jimenez-Navarro M, Simoons ML, Cleland JGF. Under-utilization of evidence-based drug treatment in patients with heart failure is only partially explained by dissimilarity to patients enrolled in landmark trials: a report from the Euro Heart Survey on Heart Failure. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2706–2713. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masson S, Latini R, Anand IS, Barlera S, Angelici L, Vago T, Tognoni G, Cohn JN. Prognostic value of changes in N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in Val-HeFT (Valsartan Heart Failure Trial) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:997–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Troughton RW, Richards AM, Yandle TG, Frampton CM, Nicholls MG. The effects of medications on circulating levels of cardiac natriuretic peptides. Ann Med. 2007;39:242–260. doi: 10.1080/07853890701232057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Troughton RW, Frampton CM, Yandle TG, Espiner EA, Nicholls MG, Richards AM. Treatment of heart failure guided by plasma aminoterminal brain natriuretic peptide (N-BNP) concentrations. Lancet. 2000;355:1126–1130. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfisterer M, Buser P, Rickli H, Gutmann M, Erne P, Rickenbacher P, Vuillomenet A, Jeker U, Dubach P, Beer H, Yoon S-I, Suter T, Osterhues HH, Schieber MM, Hilti P, Schindler R, Brunner-La Rocca H-P for the T-CHFI. BNP-guided vs symptom-guided heart failure therapy: The Trial of Intensified vs Standard Medical Therapy in Elderly Patients With Congestive Heart Failure (TIME-CHF) Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2009;301:383–392. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger R, Moertl D, Peter S, Ahmadi R, Huelsmann M, Yamuti S, Wagner B, Pacher R. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide-guided, intensive patient management in addition to multidisciplinary care in chronic heart failure: A 3-Arm, Prospective, Randomized Pilot Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;55:645–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eurlings LW, van Pol PE, Kok WE, van Wijk S, Lodewijks-van der Bolt C, Balk AH, Lok DJ, Crijns HJ, van Kraaij DJ, de Jonge N, Meeder JG, Prins M, Pinto YM. Management of chronic heart failure guided by individual N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide targets: results of the PRIMA (Can PRo-brain-natriuretic peptide guided therapy of chronic heart failure IMprove heart fAilure morbidity and mortality?) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:2090–2100. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Persson H, Erntell H, Eriksson B, Johansson G, Swedberg K, Dahlström U. Improved pharmacological therapy of chronic heart failure in primary care: a randomized Study of NT-proBNP Guided Management of Heart Failure - SIGNAL-HF (Swedish Intervention study - Guidelines and NT-proBNP AnaLysis in Heart Failure) Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:1300–1308. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lainchbury JG, Troughton RW, Strangman KM, Frampton CM, Pilbrow A, Yandle TG, Hamid AK, Nicholls MG, Richards AM. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide-guided treatment for chronic heart failure: results from the BATTLESCARRED (NT-proBNP-Assisted Treatment To Lessen Serial Cardiac Readmissions and Death) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah MR, Califf RM, Nohria A, Bhapkar M, Bowers M, Mancini DM, Fiuzat M, Stevenson LW, Connor CM. The STARBRITE Trial: a randomized, pilot study of B-type natriuretic peptide guided therapy in patients with advanced heart failure. J Cardiac Fail. 2011;17:613–621. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karlström P, Alehagen U, Boman K, Dahlström U. Brain natriuretic peptide-guided treatment does not improve morbidity and mortality in extensively treated patients with chronic heart failure: responders to treatment have a significantly better outcome. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:1096–1103. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Januzzi JL, Jr., Rehman SU, Mohammed AA, Bhardwaj A, Barajas L, Barajas J, Kim HN, Baggish AL, Weiner RB, Chen-Tournoux A, Marshall JE, Moore SA, Carlson WD, Lewis GD, Shin J, Sullivan D, Parks K, Wang TJ, Gregory SA, Uthamalingam S, Semigran MJ. Use of amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide to guide outpatient therapy of patients with chronic left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1881–1889. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jourdain P, Jondeau G, Funck F, Gueffet P, Le Helloco A, Donal E, Aupetit JF, Aumont MC, Galinier M, Eicher JC, Cohen-Solal A, Juilliere Y. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide-guided therapy to improve outcome in heart failure: The STARS-BNP Multicenter Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1733–1739. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anguita M, Esteban F, Castillo JC, Mazuelos F, Lopez-Granados A, Arizon JM, Suarez De Lezo J. Usefulness of brain natriuretic peptide levels, as compared with usual clinical control, for the treatment monitoring of patients with heart failure. Med Clin. 2010;135:435–440. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2009.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Mohammad A, Mant J, Laramee P, Swain S. Diagnosis and management of adults with chronic heart failure: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2010;341:c4130. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jessup M, Abraham WT, Casey DE, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Rahko PS, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Yancy CW. 2009 focused update: ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119:1977–2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang WH, Francis GS, Morrow DA, Newby LK, Cannon CP, Jesse RL, Storrow AB, Christenson RH, Apple FS, Ravkilde J, Wu AH. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory Medicine practice guidelines: clinical utilization of cardiac biomarker testing in heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116:e99–e109. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krum H, Jelinek MV, Stewart S, Sindone A, Atherton JJ. 2011 update to National Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand Guidelines for the prevention, detection and management of chronic heart failure in Australia, 2006. Med J Aust. 2011;194:405–409. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felker GM, Hasselblad V, Hernandez AF, O'Connor CM. Biomarker-guided therapy in chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am Heart J. 2009;158:422–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porapakkham P, Porapakkham P, Zimmet H, Billah B, Krum H. B-type natriuretic peptide-guided heart failure therapy: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:507–514. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savarese G, Trimarco B, Dellegrottaglie S, Prastaro M, Gambardella F, Rengo G, Leosco D, Perrone-Filardi P. Natriuretic peptide-guided therapy in chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis of 2,686 patients in 12 randomized trials. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e58287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riley RD, Lambert PC, Abo-Zaid G. Meta-analysis of individual participant data: rationale, conduct, and reporting. BMJ. 2010;340:c221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deberadinis B, Januzzi JL., Jr. Use of biomarkers to guide outpatient therapy of heart failure. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2012;27:661–668. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3283587c4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunlay SM, Shah ND, Shi Q, Morlan B, Van Houten H, Long KH, Roger VL. Lifetime costs of medical care after heart failure diagnosis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:68–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.957225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laramee P, Wonderling D, Swain S, Al-Mohammad A, Mant J. Cost-effectiveness analysis of serial measurement of circulating natriuretic peptide concentration in chronic heart failure. Heart. 2013;99:267–271. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:520–528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braunwald E. Biomarkers in heart failure. New Engl J Med. 2008;358:2148–2159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weir RA, Miller AM, Murphy GE, Clements S, Steedman T, Connell JM, McInnes IB, Dargie HJ, McMurray JJ. Serum soluble ST2: a potential novel mediator in left ventricular and infarct remodeling after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gullestad L, Ueland T, Kjekshus J, Nymo SH, Hulthe J, Muntendam P, Adourian A, Bohm M, van Veldhuisen DJ, Komajda M, Cleland JG, Wikstrand J, McMurray JJ, Aukrust P. Galectin-3 predicts response to statin therapy in the Controlled Rosuvastatin Multinational Trial in Heart Failure (CORONA) Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2290–2296. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Kimmenade RR, Januzzi JL, Jr., Baggish AL, Lainchbury JG, Bayes-Genis A, Richards AM, Pinto YM. Amino-terminal pro-brain natriuretic Peptide, renal function, and outcomes in acute heart failure: redefining the cardiorenal interaction? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1621–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossignol P, Cleland JG, Bhandari S, Tala S, Gustafsson F, Fay R, Lamiral Z, Dobre D, Pitt B, Zannad F. Determinants and consequences of renal function variations with aldosterone blocker therapy in heart failure patients after myocardial infarction: insights from the Eplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study. Circulation. 2012;125:271–279. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.028282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Damman K, Masson S, Hillege HL, Maggioni AP, Voors AA, Opasich C, van Veldhuisen DJ, Montagna L, Cosmi F, Tognoni G, Tavazzi L, Latini R. Clinical outcome of renal tubular damage in chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2705–2712. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]