Abstract

Purpose

To explain why very preterm newborns who develop retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) appear to be at increased risk of abnormalities of both brain structure and function.

Methods

A total of 1,085 children born at <28 weeks’ gestation had clinically indicated retinal examinations and had a developmental assessment at 2 years corrected age. Relationships between ROP categories and brain abnormalities were explored using logistic regression models with adjustment for potential confounders.

Results

The 173 children who had severe ROP, defined as prethreshold ROP (n = 146) or worse (n = 27) were somewhat more likely than their peers without ROP to have brain ultrasound lesions or cerebral palsy. They were approximately twice as likely to have very low Bayley Scales scores. After adjusting for risk factors common to both ROP and brain disorders, infants who developed severe ROP were at increased risk of low Bayley Scales only. Among children with prethreshold ROP, exposure to anesthesia was not associated with low Bayley Scales.

Conclusions

Some but not all of the association of ROP with brain disorders can be explained by common risk factors. Most of the increased risks of very low Bayley Scales associated with ROP are probably not a consequence of exposure to anesthetic agents.

Very preterm newborns who develop severe retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) are more likely than their peers unaffected by ROP to have evidence of brain damage, including cerebral palsy,1 developmental delay,1 “severe disability,”2 and lower scores on measures of verbal and performance IQ,3 general conceptual ability,4 and spatial ability.4 The retina and brain are linked by the optic nerve and vasculature as well as by shared vulnerability to certain disease risk factors. Among the most well studied antecedents shared by retinopathy of prematurity and encephalopathy of prematurity (and their presumed consequences) are immaturity (low gestational age and its correlates), abnormally high Scores for Neonatal Acute Physiology, hyperoxemia, bacteremia, fetal and postnatal growth restriction, and prolonged ventilator assistance (for references, see e-Supplement 1, paragraph 1, available at jaapos.org). The purpose of the present study was to evaluate how much of the association between ROP and brain disorders can be explained by these shared antecedents. To our knowledge, this is the first such study to appear in the literature.

Subjects and Methods

The Extremely Low Gestational Age Newborn (ELGAN) Study was designed to identify characteristics and exposures that increase the risk of structural and functional neurological disorders in extremely low gestational age newborns (ELGANs).5 During the years 2002–2004, women who delivered before 28 weeks’ gestation at one of 14 participating institutions were invited to enroll in the study. The enrollment and consent processes were approved by the individual institutional review boards. A total of 1,249 mothers of 1,506 infants consented. Of the 1,200 children who survived to age 2 years post-term equivalent, 1,085 who had an eye examination for ROP while in the intensive care nursery and a developmental assessment at 24 months form the sample for the present study.

Demographic, Pregnancy, and Newborn Variables

The clinical circumstances that led to each maternal admission and ultimately to each preterm delivery were operationally defined using both data from the maternal interview and data abstracted from the medical record.6 The gestational age estimates were based on a hierarchy of the quality of available information.5

The birth weight Z-score is the number of standard deviations the infant’s birth weight is above or below the mean weight of infants of the same gestational age in a standard data set.7 Children whose birth weight Z-score was −2 (ie, more than 2 standard deviations below the mean in the standard data set) are identified as severely growth restricted, whereas those whose birth weight Z-score was ≥ −2 but < −1 (ie, between 1 and 2 standard deviations below the mean) are identified as moderately growth restricted.

Physiology, laboratory, and therapy data needed to calculate a Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology-II (SNAP-II) were collected during the first 12 postnatal hours.8 The present study classified newborns as having a SNAP-II in the highest quartile or in the lower three quartiles.

ELGANs were classified as hyperoxemic if their highest PaO2 within gestational age categories (23–24, 25–26, 27 weeks) on postnatal days 1, 2, and 3 was in the highest quartile. Because an extreme measure on one day could reflect a fleeting event, an infant had to be in the extreme quartile on at least 2 of the 3 days to be considered “exposed” to elevated oxygen concentrations.

Infants were classified by the cumulative number of days they received mechanical ventilation (either high-frequency or conventional mechanical ventilation) during the first month. Here we dichotomized infants by whether or not they were ventilated for at least 14 days.

Documented bacteremia was defined as recovery of an organism from blood drawn during the first postnatal month. Specific organisms were not identified.

Growth velocity, a measure of average daily weight gain between days 7 and 28, is defined as the difference between the day 28 and day 7 weights divided by the weight on day 7, and then divided once again by 21 (the number of days between days 7 and 28). This number was multiplied by 1000 to express growth velocity in gms/kg/day, so that GV7–28 = 1000 × ((wt28 – wt7)/wt7)/21. Infants were again classified as either in the top or lower three quartiles of growth velocity.

Eye Examinations

Participating ophthalmologists helped prepare a manual and data collection form and then participated in efforts to minimize observer variability. Definitions of terms were those accepted by the International Committee for Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP).9 In keeping with guidelines during enrollment,10 the first ophthalmologic examination was by 31 weeks’ postmenstrual age or 4 weeks actual age, whichever was later. Follow-up examinations were performed as clinically indicated until vascularization extended into zone III or until disease regression was evident. The present study defined severe ROP according to previously published criteria11–13: (1) stage 3 or higher, (2) zone I disease, (3) any prethreshold or worse, and (4) plus disease. The comparison groups always include infants with nonsevere or no ROP.

Protocol Ultrasound Scans

Procedures for obtaining and reading ultrasound scans are reported elsewhere.14,15 The three sets of protocol scans were defined by the postnatal day on which they were obtained. Protocol 1 scans were obtained between days 1 and 4; protocol 2 scans were obtained between days 5 and 14; and protocol 3 scans were obtained between day 15 and week 40.

Developmental Assessment at 24 months

Certified examiners administered and scored the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (2nd ed).16 Main outcomes were a Mental Development Index (MDI) and a Psychomotor Development Index (PDI) <55 because that score is 3 standard deviations below the expected mean and therefore constitutes a severe impairment and because the predictive ability of indices <55 is higher than that of scores <70, which is 2 standard deviations below the expected mean.17 Procedures to standardize the neurological examination and minimize examiner variability are presented elsewhere.18 The topographic diagnosis of CP (quadriparesis, diparesis, or hemiparesis) was based on an algorithm using these data.19

Data Analysis

The null hypothesis is that infants who had severe ROP were not at increased risk of any brain structure or function abnormality. First, how gestational age and birth weight were associated with severe forms of ROP was evaluated (Table 1). Second, the frequency that infants with and without severe forms of ROP had ultrasound-defined brain lesions, low indices of mental and motor development, and forms of cerebral palsy and small head circumference was explored (Table 2). To gauge how the association between ROP and brain disorders can be explained by potential confounders, logistic regression models of these brain structure and function abnormalities associated with risk of severe forms of ROP were created. The models permitted calculation of odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals after adjustment for gestational age, birth weight Z-score categories, hyperoxemia (a PaO2 in the highest quartile on 2 of the first 3 postnatal days), SNAP-II in the highest quartile, culture-proven bacteremia in the first 28 days, mechanical or high frequency on 14 or more days, and growth velocity in the lowest quartile (Table 3).

Table 1.

Percentage of newborns with specific ROP and birth characteristics

| Retinopathy of prematurity | Gestational age, weeks | Birth weight Z-score | Maximum row N |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23–24 | 25–26 | < −2 | ≥ −2, < −1 | ||

| Stage | |||||

| 3–5 | 37 | 50 | 10 | 17 | 305 |

| ≤3 | 14 | 45 | 4 | 12 | 780 |

| Plus disease | |||||

| Yes | 48 | 45 | 9 | 20 | 119 |

| No | 17 | 46 | 5 | 12 | 966 |

| Zone I | |||||

| Yes | 46 | 53 | 62 | 36 | 83 |

| No | 18 | 46 | 34 | 45 | 1002 |

| Surgery indication | |||||

| Threshold ROPb | 63 | 33 | 11 | 33 | 27 |

| Type 1 prethreshold ROPc | 45 | 49 | 10 | 18 | 146 |

| Neither | 16 | 46 | 5 | 12 | 939 |

| Maximum column N | 219 | 503 | 58 | 143 | 1085 |

Numbers are row percentages.

Satisfied CRYO-ROP criteria for ablative surgery.

Satisfied ET-ROP criteria for ablative surgery.

Table 2.

Percentage of newborns with specific ROP and brain-related characteristicsa

| Retinopathy of prematurity |

Ultrasound lesions | MDI <55 | PDI <55 | Cerebral palsy (-paresis) | HCZ ≤ −2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VMa | HOLb | Quadri- | Di- | Hemi- | ||||

| Stage | ||||||||

| 3–5 | 13 | 9 | 24 | 23 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 18 |

| ≤3 | 9 | 6 | 11 | 13 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 7 |

| Plus disease | ||||||||

| Yes | 15 | 13 | 30 | 30 | 11 | 8 | 3 | 19 |

| No | 9 | 6 | 13 | 14 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 9 |

| Zone 1 | ||||||||

| Yes | 16 | 13 | 25 | 20 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 18 |

| No | 9 | 6 | 14 | 16 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 10 |

| Surgery indication | ||||||||

| Threshold ROPb | 22 | 15 | 38 | 33 | 12 | 8 | 0 | 24 |

| Type 1 prethreshold | 14 | 11 | 28 | 29 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 19 |

| Neither | 9 | 6 | 13 | 14 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 9 |

| Maximum column N | 108 | 76 | 151 | 160 | 64 | 37 | 19 | 106 |

HCZ, head circumference Z-score; HOL, hypoechoic lesion; MDI, Mental Development Index; PDI, Psychomotor Development Index; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity; VM, ventriculomegaly.

Numbers are row percentages.

Satisfied CRYO-ROP criteria for ablative surgery.

Table 3.

Odds ratios (and 95% CIs) of specific brain structure abnormality or dysfunction identified and retinopathy characteristicsa

| Retinopathy of prematurity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 3+ | Plus disease | Zone 1 | Threshold | Prethreshold | |

| Ultrasound lesions | |||||

| Ventriculomegaly | 1.2 (0.8–2.0) | 1.3 (0.7–2.3) | 1.1 (0.5–2.1) | 2.3 (0.8–6.5) | 1.0 (0.6–1.8) |

| Hypoechoic lesion | 1.2 (0.7–2.1) | 1.8 (0.9–3.5) | 1.8 (0.8–4.0) | 3.4 (0.99–12) | 1.3 (0.7–2.6) |

| Bayley Scales MDI | |||||

| <55 | 1.9 (1.2–2.9) | 1.9 (1.1–3.2) | 1.5 (0.8–2.9) | 2.2 (0.8–6.2) | 1.7 (1.00–2.7) |

| 55–69 | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 2.1 (1.1–4.0) | 2.4 (1.2–4.7) | 3.6 (1.3–10) | 2.1 (1.2–3.8) |

| Bayley Scales PDI | |||||

| <55 | 1.6 (1.03–2.4) | 1.8 (1.1–3.1) | 1.1 (0.6–2.2) | 1.8 (0.6–5.0) | 1.9 (1.1–3.1) |

| 55–69 | 1.6 (1.03–2.5) | 1.4 (0.7–2.6) | 2.2 (1.2–4.2) | 2.1 (0.7–6.6) | 1.6 (0.9–2.9) |

| Cerebral palsy | |||||

| Quadriparesis | 1.2 (0.7–2.0) | 1.2 (0.6–2.6) | 0.9 (0.4–2.3) | 1.3 (0.3–4.8) | 0.9 (0.5–1.9) |

| Diparesis | 1.2 (0.5–2.7) | 2.4 (0.99–5.9) | 2.1 (0.8–6.0) | 1.5 (0.3–7.6) | 2.2 (0.9–5.2) |

| Hemiparesis | 1.1 (0.4–3.1) | 1.3 (0.3–4.9) | 1.0 (0.2–5.1) | ---- | 0.9 (0.2–3.3) |

| Head circ Z-score | |||||

| < −2 | 1.6 (1.00–2.6) | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) | 1.7 (0.8–3.5) | 1.6 (0.5–4.8) | 1.2 (0.7–2.1) |

| ≥ −2, < −1 | 1.0 (0.7–1.6) | 1.0 (0.6–1.7) | 1.9 (1.04–3.5) | 1.4 (0.5–3.9) | 1.0 (0.6–1.7) |

The referent group for these analyses comprises children who did not have that retinopathy characteristic. Logistic regression models adjusted for gestational age, birth weight Z-score PaO2 in the highest quartile on 2 or more of the first 3 postnatal days, culture-proven bacteremia in weeks 2 to 4, growth velocity in the lowest quartile, SNAP-II in the highest quartile, and mechanical or high frequency on 14 or more days.

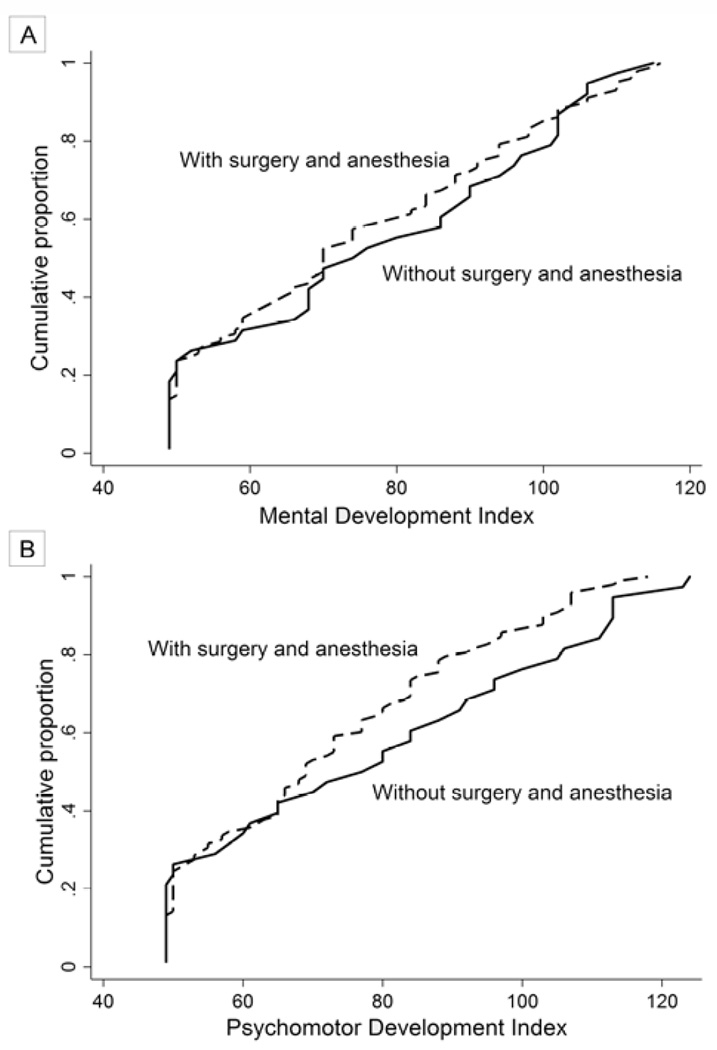

The criteria for retinal ablation (by cryotherapy and/or laser photocoagulation) to preserve vision in infants who developed severe retinopathy of prematurity were expanded at the end of 2003 from confining therapy to infants with threshold disease (CRYO-ROP criteria)20 to include infants with type 1 ROP (ETROP criteria).21 This allowed us to compare the 38 infants who had type 1 ROP and peripheral retinal ablation to their 98 peers with type 2 ROP who did not (Table 4 and Figure 1).

Table 4.

Distribution of Mental Development Indices (MDI) and Psychomotor Development Indices (PDI) among children who had prethreshold disease comparing those who had surgery to those who did not

| Surgery | Row N | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Bayley Scales MDI | |||

| <55 | 26 | 29 | 38 |

| 55–69 | 16 | 18 | 24 |

| ≥70 | 58 | 53 | 74 |

| Bayley Scales PDI | |||

| <55 | 30 | 26 | 39 |

| 55–69 | 22 | 16 | 28 |

| ≥70 | 48 | 58 | 69 |

| Column N | 38 | 98 | 136 |

Numbers are column percentages.

FIG 1.

The cumulative frequency of Mental Development Index (A) and Psychomotor Development Index (B) among children who developed prethreshold ROP for those who were and were not exposed to ablative surgery and anesthesia.

Results

Children with severe ROP were more likely than others to have been born at a very low gestational age (23–24 weeks) and growth restricted (Table 1). They were also more likely to have ventriculomegaly and a hypoechoic lesion identified on an ultrasound scan of the brain (Table 2).

The percentage of children with a Bayley Scale of Infant Development Index, whether mental or psychomotor, >3 standard deviations below the mean (ie, <55) at age 2 years was most prominently increased among those with severe ROP (Table 2). The risk of an index 2–3 standard deviations below the mean (ie, 55–69) was also increased, but not as prominently.

Overall, children with severe ROP were more likely than others to be given a diagnosis of quadriparetic or diparetic cerebral palsy at age 2 years (Table 2). Only those who developed stage 3 or higher ROP were more likely than others to develop hemiplegic cerebral palsy.

At age 2 years, a head circumference >2 standard deviations below the expected mean was more common among those whose ROP had been severe than among others (Table 2). To a lesser extent, a head circumference of 1–2 standard deviations below the expected mean also was more common among those who had severe ROP.

To calculate the risk of developing each of the brain abnormalities displayed in Table 2, we compared children who had each form of severe ROP to all others with either less severe or no ROP, adjusting for potential confounders (Table 3). Children who had plus disease and/or stage 3+ ROP were at significantly increased risk of an MDI <55, while those who had prethreshold ROP were at borderline significantly increased risk. The risk of an MDI of 55–69 was significantly increased among children who developed plus, zone I, threshold, and/or prethreshold disease.

The increased risk of a PDI <55 was statistically significant for plus disease, stage 3+ ROP and/or prethreshold disease, while the increased risk of a PDI of 55–69 was statistically significant for stage 3+ ROP and for zone 1 ROP (Table 3). The risks of ventriculomegaly, a hypoechoic lesion, a cerebral palsy diagnosis and of microcephaly were not significantly increased, regardless of the indicator of ROP severity.

Among all children who developed prethreshold disease, those who had retinal ablation surgery, many of whom were exposed to general anesthetic agents, had a distribution of Mental and Psychomotor Development Indices that differed minimally from those of children who did not have retinal surgery (Table 4). The cumulative frequency of MDIs and PDIs among those who had retinal surgery was very similar to the pattern seen in those who did not (Figure 1). Fully 31% of children who had retinal surgery also had another form of surgery, most often patent ductus ligation, while 18% of children with prethreshold disease who did not have retinal surgery had surgery for another indication, again, most commonly for ligation of a patent ductus arteriosus.

Discussion

The main findings of this study are that children who developed severe ROP were more likely than their peers to have Bayley Scales of Mental and Psychomotor Development of 2–3 standard deviations below the expected mean. For stage 3 or higher ROP and for plus disease, the increased risk was >3 standard deviations below the expected mean. We also found that the risk of a head circumference of 1–2 standard deviations below the mean was associated with zone I ROP. And finally, among children who developed prethreshold disease, those who received ablative surgery (often with general anesthesia) had a distribution of Bayley Scales of Mental and Psychomotor Development that was similar to that of their peers who did not have surgery (or anesthesia). These findings may be interpreted in light of two causal models. In model 1, ROP and structural/functional brain damage share risk factors. In model 2, some characteristic associated with one of these entities (eg, general anesthesia) increases the risk of the other.

Model 1: Shared Risk Factors

Inflammation is perhaps the most prominent antecedent of ventriculomegaly seen on brain ultrasound scan,25 low Bayley Scales of Infant Development,26 and microcephaly years after birth.27 Inflammatory phenomena also appear to place a newborn at heightened risk of ROP.12,13,28,29 Consequently, we consider exposures and characteristics that contribute to inflammation.

The preterm newborn is at increased risk of infection30,31 and inflammation.32 The very preterm infant’s inflammatory response tends to be strong and does not seem to resolve as readily as that of more mature newborns (for references, see e-Supplement 1, paragraph 2). The tendency to achieve and prolong a proinflammatory state may very well reflect multiple processes that vary with gestational age and place ELGANs at heightened risk of retina and brain damage.33–36

A paucity of growth factors might result in heightened vulnerability.37 Although primarily needed for normal development, these growth factors are capable of protecting the developing brain and retina against potential injurious exposures.38–41 In essence, the fetus/newborn is first able to synthesize adequate amounts of some of these proteins sometime between the weeks 30 and 40 of gestation.42 In utero the fetus would have adequate amounts provided by the mother or placenta. Ex utero the ELGAN is deprived of some of what might be very helpful.

This temporal pattern of regulation that varies with gestational age is exemplified by the synthesis of IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor-1), which appears to protect against retinopathy and brain damage, and by the synthesis of BDNF (brain derived neurotropic factor), which also appears to protect against retinopathy, and brain damage (for references, see e-Supplement 1, paragraph 3). Developmental processes unique to the preterm brain, such as myelinogenesis, appear to account for the heightened brain vulnerability.43 Similarly, processes unique to the preterm retina, for example, angiogenesis, appear to account for the retina’s heightened vulnerability.44 It is possible that there are other relevant common antecedents, for example, a low IGF-1 concentration. Unfortunately, we did not measure IGF-1 and thus cannot adjust for low IGF-1 blood concentrations.

Model 2: Brain Damage among ROP Infants Reflects Anesthesia Neurotoxicity

Anesthetic-induced developmental neurotoxicity (AIDN) refers to neurotoxicity attributed to uneventful anesthesia exposures in human newborns or infants.45 Although evidence continues to support the concept that the developing brain is vulnerable to the adversities associated with general anesthesia,46 the clinical relevance remains unsettled.47

In the present study the children who were exposed to surgery (with or without general anesthesia) for their type 1 ROP had MDIs and PDIs similar to those of children who did not undergo surgery for their prethreshold disease. Thus we cannot attribute the low indices among children with severe ROP to anesthesia and consider Model 2 to be highly unlikely.

Ours is an observational study with all the limitations that preclude causal inferences. Interval and not continuous data were all that could be collected. The sickest infants were more likely to be treated aggressively than those who were less sick, making our study prone to confounding by indication.22,23 In addition, we are uncertain about the general anesthesia exposure of some of our subjects who received retinal ablation surgery. The strengths of this study include the large number of infants with only modest attrition, selection of infants based on gestational age and not birth weight,24 and procedures to minimize observer variability.15,19

It is certainly possible that diminished visual acuity secondary to severe ROP contributed to lowering the Bayley Scales of Infant Development. Yet it is highly unlikely that diminished visual acuity contributed to such drastic reductions. Thus it behooves us to consider alternative explanations for associations between severe ROP and severely low Bayley Scales.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of their ELGAN Study colleagues: Bhavesh L. Shah, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Massachusetts; Camilia Martin, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts; Linda Van Marter, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; Robert Insoft, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; Francis Bednarek (deceased), University of Massachusetts Memorial Health Center, Worcester, Massachusetts; Cynthia Cole, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts; Richard A. Ehrenkranz, Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital, New Haven, Connecticut; Stephen C. Engelke, University Health Systems of Eastern Carolina, Greenville, North Carolina; Carl Bose, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina; Mariel Poortenga, Helen DeVos Children's Hospital, Grand Rapids, Michigan; Padima Karna, Sparrow Hospital, Lansing, Michigan; Michael D. Schreiber, University of Chicago Hospital, Chicago Illinois; Daniel Batton, William Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak Michigan; Kenneth Wood, Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation, Amherst, New York; Deborah Hirtz, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, MD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hungerford J, Stewart A, Hope P. Ocular sequelae of preterm birth and their relation to ultrasound evidence of cerebral damage. Br J Ophthalmol. 1986;70:463–468. doi: 10.1136/bjo.70.6.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Msall ME, Phelps DL, DiGaudio KM, et al. Severity of neonatal retinopathy of prematurity is predictive of neurodevelopmental functional outcome at age 5.5 years. Behalf of the Cryotherapy for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group. Pediatrics. 2000;106:998–1005. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.5.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooke RW, Foulder-Hughes L, Newsham D, Clarke D. Ophthalmic impairment at 7 years of age in children born very preterm. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89:F249–F253. doi: 10.1136/adc.2002.023374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stephenson T, Wright S, O’Connor A, et al. Children born weighing less than 1701 g: visual and cognitive outcomes at 11–14 years. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92:F265–F270. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.104000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Shea TM, Allred EN, Dammann O, et al. The ELGAN study of the brain and related disorders in extremely low gestational age newborns. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85:719–725. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2009.08.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McElrath TF, Hecht JL, Dammann O, et al. Pregnancy disorders that lead to delivery before the 28th week of gestation: an epidemiologic approach to classification. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:980–999. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yudkin PL, Aboualfa M, Eyre JA, Redman CW, Wilkinson AR. New birthweight and head circumference centiles for gestational ages 24 to 42 weeks. Early Hum Dev. 1987;15:45–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(87)90099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richardson DK, Corcoran JD, Escobar GJ, Lee SK. SNAP-II and SNAPPE-II: simplified newborn illness severity and mortality risk scores. J Pediatr. 2001;138:92–100. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.109608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Committee for the Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity. An international classification of retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:1130–1134. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030908011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Screening examination of premature infants for retinopathy of prematurity. Pediatrics. 2001;108:809–811. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hauspurg AK, Allred EN, Vanderveen DK, et al. Blood Gases and Retinopathy of Prematurity: the ELGAN Study. Neonatology. 2010;99:104–111. doi: 10.1159/000308454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen ML, Allred EN, Hecht JL, et al. Placenta microbiology and histology, and the risk for severe retinopathy of prematurity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:7052–7058. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tolsma KW, Allred EN, Chen ML, et al. Neonatal bacteremia and retinopathy of prematurity: the ELGAN Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:1555–1563. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teele R, Share J. Ultrasonography of infants and children. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuban K, Adler I, Allred EN, et al. Observer variability assessing US scans of the preterm brain: the ELGAN study. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:1201–1208. doi: 10.1007/s00247-007-0605-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts G, Anderson PJ, Doyle LW. The stability of the diagnosis of developmental disability between ages 2 and 8 in a geographic cohort of very preterm children born in 1997. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:786–790. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.160283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuban KC, O’Shea M, Allred E, et al. Video and CD-ROM as a training tool for performing neurologic examinations of 1-year-old children in a multicenter epidemiologic study. J Child Neurol. 2005;20:829–831. doi: 10.1177/08830738050200101001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuban KCK, Allred EN, O’Shea TM, et al. An algorithm for diagnosing and classifying cerebral palsy in young children. J Pediatr. 2008;153:466.e1–472.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer EA, Flynn JT, Hardy RJ, et al. the Cryotherapy for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group. Incidence and early course of retinopathy of prematurity. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1628–1640. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Early Treatment for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group. Revised indications for the treatment of retinopathy of prematurity: results of the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity randomized trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:1684–1694. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.12.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker AM. Confounding by indication. Epidemiology. 1996;7:335–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Signorello LB, McLaughlin JK, Lipworth L, Friis S, Sorensen HT, Blot WJ. Confounding by indication in epidemiologic studies of commonly used analgesics. Am J Ther. 2002;9:199–205. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnold CC, Kramer MS, Hobbs CA, McLean FH, Usher RH. Very low birth weight: a problematic cohort for epidemiologic studies of very small or immature neonates. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:604–613. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leviton A, Kuban K, O’Shea TM, et al. The Relationship between early concentrations of 25 blood proteins and cerebral white matter injury in preterm newborns: the ELGAN Study. J Pediatr. 2011;158:897.e5–903.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Shea TM, Allred EN, Kuban K, et al. Elevated concentrations of inflammation-related proteins in postnatal blood predict severe developmental delay at two years in extremely premature infants. J Pediatr. 2012;160:395.e4–401.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.08.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leviton A, Kuban KC, Allred EN, et al. Early postnatal blood concentrations of inflammation-related proteins and microcephaly two years later in infants born before the 28th post-menstrual week. Early Hum Dev. 2011;87:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J, Dammann O. Perinatal infection, inflammation, and retinopathy of prematurity. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;17:26–29. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JW, McElrath T, Chen M, et al. Pregnancy disorders appear to modify the risk for retinopathy of prematurity associated with neonatal hyperoxemia and bacteremia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26:811–818. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.764407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cuenca AG, Wynn JL, Moldawer LL, Levy O. Role of innate immunity in neonatal infection. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30:105–112. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1333412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sherman MP. New concepts of microbial translocation in the neonatal intestine: mechanisms and prevention. Clin Perinatol. 2010;37:565–579. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bose CL, Laughon MM, Allred EN, et al. Systemic inflammation associated with mechanical ventilation among extremely preterm infants. Cytokine. 2013;61:315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dammann O, Leviton A. Biomarker epidemiology of cerebral palsy. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:158–161. doi: 10.1002/ana.20014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dammann O. Persistent neuro-inflammation in cerebral palsy: a therapeutic window of opportunity? Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:6–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dammann O. Inflammation and Retinopathy of Prematurity. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:975–977. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01836.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gille C, Dreschers S, Leiber A, et al. The CD95/CD95L pathway is involved in phagocytosis-induced cell death of monocytes and may account for sustained inflammation in neonates. Pediatr Res. 2013;73:402–408. doi: 10.1038/pr.2012.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dammann O, Leviton A. Brain damage in preterm newborns: might enhancement of developmentally-regulated endogenous protection open a door for prevention? Pediatrics. 1999;104:541–550. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.3.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leviton A, Paneth N, Reuss ML, et al. Hypothyroxinemia of prematurity and the risk of cerebral white matter damage. J Pediatr. 1999;134:706–711. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70285-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reuss ML, Paneth N, Pinto-Martin JA, Lorenz JM, Susser M. The relation of transient hypothyroxinemia in preterm infants to neurologic development at two years of age. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:821–827. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603283341303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Semkova I, Krieglstein J. Neuroprotection mediated via neurotrophic factors and induction of neurotrophic factors. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1999;30:176–188. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tabakman R, Lecht S, Sephanova S, Arien-Zakay H, Lazarovici P. Interactions between the cells of the immune and nervous system: neurotrophins as neuroprotection mediators in CNS injury. Prog Brain Res. 2004;146:387–401. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(03)46024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanders EJ, Harvey S. Peptide hormones as developmental growth and differentiation factors. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:1537–1552. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Back SA, Riddle A, McClure MM. Maturation-dependent vulnerability of perinatal white matter in premature birth. Stroke. 2007;38:724–730. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000254729.27386.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quinn GE, Gilbert C, Darlow BA, Zin A. Retinopathy of prematurity: an epidemic in the making. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:2929–2937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCann ME, Soriano SG. Perioperative central nervous system injury in neonates. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109(Suppl 1):i60–i67. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCann ME, Soriano SG. General anesthetics in pediatric anesthesia: influences on the developing brain. Curr Drug Targets. 2012;13:944–951. doi: 10.2174/138945012800675768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davidson AJ. Anesthesia and neurotoxicity to the developing brain: the clinical relevance. Paediatr Anaesth. 2011;21:716–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.