Abstract

Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) has been shown to evolve from a relatively slowly replicating and mildly cytopathic virus early in the infection (SIVMneCL8) to a faster replicating and more cytopathic virus at later stages of the infection (SIVMne170). It has recently been demonstrated that the early and mildly cytopathic variant SIVMneCL8 out-competed the late and highly cytopathic strain SIVMne170 in cell culture experiments, because the fitness disadvantage derived from the higher cytopathicity was not matched by a sufficient increase in the viral replication rate. However, in another set of experiments where the life span of cells in culture was artificially limited, the late and more cytopathic virus won the competition, because under this condition cytopahticity was not an important determinant of viral fitness. It was hypothesized that the limited life span experiment reflected the immune-mediated high turnover environment in vivo more accurately, and that the presence of immune responses accounts for the selection of the cytopathic strain SIVmne170 during later stages of the infection. This paper investigates the effect of immune responses, in particular cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses, on the competition dynamics between these two SIV strains with the help of mathematical models. Model analysis and parameter estimates derived from previously published data on SIV growth kinetics suggest that the SIV-specific CTL response might not be the driving force that leads to the selection of the cytopathic strain SIVMne170 during later stages of the infection. This implies that more complex evolutionary mechanisms might have to be invoked in order to explain the emergence of these strains in vivo. One possibility is that the ability of multiple virus particles to infect the same cell (coinfection) might be a prerequisite for the emergence of the cytopathic strain SIVMne170 as the disease progresses.

1. Introduction

Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) is an animal model for HIV infection and the two viruses share many characteristics of disease progression (Kimata et al. 1999). Initial infection results in an acute phase where virus load rises to high levels and the CD4 T helper cells, the targets for the virus, drop to relatively low levels, especially in the gut associated lymphoid tissue (Veazey et al. 1998). Subsequently, immune responses rise, and this induces a down-regulation of virus load to lower levels, marking the beginning of the asymptomatic phase. Over time, virus load eventually increases to relatively high levels, marking the onset of AIDS. A major difference between experimental SIV infection and HIV infection of humans is that SIV infection progresses to AIDS over a shorter period of time.

In a set of experiments, macaques were inoculated with a relatively slowly replicating and mildly cytopathic strain, called SIVMneCL8. As the disease progressed towards AIDS at later stages, a faster replicating and more cytopathic virus has been isolated, called SIVMne170 (Kimata 2006; Kimata and Overbaugh 1997). The fitness of these two virus strains has recently been compared by in vitro competition experiments, using CEMx174 cells (Voronin et al. 2005). In basic competition experiments, the early stage virus SIVMneCL8 had a higher fitness and outcompeted the late stage virus SIVMne170. The reason was as follows. While the late virus replicated with a faster rate than the early virus, it also showed a significantly higher degree of cytopathicity, killing the infected cells with a faster rate. While a faster replication rate increases viral fitness, a higher cytopathicity decreases viral fitness. The increased cytopathicity in the late stage virus was not matched by a sufficient increase in the viral replication rate, thus resulting in a reduced net fitness. This experiment was repeated with the addition, that the life-span of the target cells was limited by removing them from culture after a certain period of time (Voronin et al. 2005). Under this condition, the life-span of the cells was less than 2 days, independent of viral replication. Now, the opposite result was observed. The late stage virus SIVMne170 had a higher fitness and outcompeted the early stage virus SIVMneCL8. The reason is that now the infected cells die before the virus had a chance to kill them. Therefore, differences in viral cytopathicity do not impact viral fitness significantly, while the higher replication rate of the late stage viruses increases viral fitness. It was argued that limiting the life-span of cells in culture is a more realistic experiment because immune responses in vivo generate a rapid turnover environment (Voronin et al. 2005). It was concluded that the presence of a CTL response can account for the selection of the more cytopathic SIV strain during later stages of the infection. It was speculated that at early stages of the infection, the life-span of cells is longer because killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) is not important. This provides an advantage for non-cytopathic viruses which are amplified by selection. At later times, under conditions of rapid turnover, however, being non-cytopathic does not provide an advantage anymore, and the variant with the faster replication rate is selected (Voronin et al. 2005). While other factors can also contribute to a higher turnover environment in vivo compared to the in vitro experiments (such as a higher death rate of activated cells in vivo or bystander cell death), CTL responses have been shown to be actively fighting the virus and are likely to be a very important factor that determines the life span of infected cells. Also, the effectiveness of CTL responses can vary in different stages of the infection and could thus potentially account for the selection of different viral variants during different phases of the disease.

This paper uses mathematical models to examine the competition dynamics between SIVMneCL8 and SIVMne170, especially focusing on the effect of a specific CTL response on the outcome of competition. This analysis, and parameter estimates derived from the literature, suggest that the presence of the SIV-specific CTL response might not account for the selection of the more cytopathic strain SIVMne170 during later stages of the infection. If this is true other, more complex mechanisms must account for the rise of the cytopathic strain observed in vivo. It is speculated that the ability of multiple virus strains to infect the same cell (coinfection) could account for the observed evolutionary dynamics.

The article starts by looking at basic in vivo competition dynamics between two virus strains in the absence of any immune responses. Then an SIV-specific CTL response is added to the equations. Based on published experimental data on SIV replication in vivo and in vitro, an attempt is made to obtain crucial parameter estimates.

2. Basic competition dynamics without immune responses

We build on the standard model of infection dynamics (De Boer and Perelson 1998; Nowak and Bangham 1996; Perelson 2002) which has been used to describe the spread of a virus through a population of host cells. Instead of considering one virus population, the model takes into account two virus populations which differ in their rate of replication and in their cytopathicity. Therefore, the model contains the following variables: uninfected host cells, x, cells infected with virus strain 1, y1, and cells infected with virus strain 2, y2. Note that the model does not include a variable that describes the number of free viruses. This is because the population of free viruses turns over with a significantly faster rate than the population of infected cells. It is therefore assumed that the free virus population is in a quasi-steady state. For a review of general virus dynamics models, see (Nowak and May 2000). The model is given by the following set of ordinary differential equations which describe the development of these populations over time.

| (1) |

Uninfected host cells are produced with a rate λ and are characterized by a natural death rate, d. They become infected by virus strain 1 with a rate β1, and by virus strain 2 with a rate β2. Infected cells die with a rate d+a1 and d+a2, respectively. These death rates are a composite between the natural death rate, d, and the virus-induced death rate, a (cytopathicity). If the cell is naturally long lived, then the value of d is low relative to the value of a, and the viral cytopathicity is the major determinant of the life-span of infected cells. On the other hand, if the cell is naturally short lived, then the value of d is large relative to the value of a, and the viral cytopahticity is not a significant determinant of the life span of infected cells.

While this model will be analyzed in general terms, it is important to point out that in the SIV situation described above, the replication kinetics and cytopathicity parameters are linked. The early strain SIVmneCL8 is not only less cytopathic, it also replicates slower. On the other hand, the late strain SIVMne170 is more cytopathic, but also replicates faster. Data indicate that the increase in cytopathicity observed for the late strain SIVMne170 is higher than the increase in the replication rate (Voronin et al. 2005). While I do not include an explicit relationship between the viral replication rate, β, and the viral cytopathicity, a, this correlation will be kept in mind when using the model to interpret the experiments and data regarding the growth kinetics of the early and late SIV strains. Therefore, many aspects of the model discussed here have direct counter-parts in the extensive literature on the evolution of virulence, e.g. (Anderson and May 1982; Ebert and Herre 1996; Ebert and Mangin 1997; Frank 1996), and are therefore not novel. However, the focus of the paper is different: the aim is to apply these models to the data on SIV growth kinetics and investigate more deeply whether the presence of CTL indeed can account for the rise of a cytopathic strain during the late stages of the infection, or whether other explanations will have to be invoked.

This model can be used to explore the high-turnover argument made by (Voronin et al. 2005) in the context of in vivo infection dynamics. In the absence of immune responses, this simply means that the natural death rate of susceptible cells is high relative to the virus-induced death rate of infected cells. That is, the value of d is large relative to the value of a. We will assume that virus strain 1 is slow and mildly cytopathic, while virus strain 2 is faster and strongly cytopathic. We will further assume that the difference between the two strains in the cytopathicity is higher than the difference in the replication rate, as shown by (Voronin et al. 2005).

In this model, each virus in isolation can establish a successful infection in the host if its basic reproductive ratio, R0, is greater than one (Anderson and May 1991). From now on, it is assumed that this will be the case. The basic reproductive ratio of the virus describes the average number of newly infected cells generated by one infected cell at the beginning of the infection. For further information regarding the concept of R0 in the context of in vivo virus dynamics, see (Nowak and May 2000). In the model presented here, it is given by R01 = λβ1/[d(a1+d)] and R02 = λβ1/[d(a1+d)], respectively. Assuming that both viruses can establish a successful infection on their own, two outcomes can be observed if they simultaneously infect the same host, and are thus in competition with each other.

Virus 1 wins and drives virus 2 extinct. This is described by the following equilibrium expressions. x*=(d+a1)/β1, y*1=λ/(d+a1) − d/β1, y*2=0.

Virus 2 wins and drives virus 1 extinct. This is described by the following equilibrium expressions. x̂=(d+a2)/β2, ŷ1=0, ŷ2= λ/(d+a2) − d/β2.

The relative value of R0 determines the outcome of competition. The virus strain with the higher basic reproductive ratio wins and out-competes the other virus strain. Both the viral replication rate, β, and the viral cytopathicity, a, influence the basic reproductive ratio of the virus. From the expressions, it is clear that both the viral replication rate and the viral cytopathicity influence the basic reproductive ratio of the virus to a similar degree if the natural death rate of cells is low (low value of d). In this case, the less cytopathic virus wins, because we assume that there is a higher difference in the cytopathicity between the virus strains compared to the difference in the viral replication rate (Figure 1a). In other words, the fitness reduction as a result of high cytopathicity was not matched by a sufficient increase in the viral replication rate. However, if the natural death rate of cells is high (high value of d), the basic reproductive ratio of the virus does not depend significantly on the viral cytopathicity, a. In this case, the faster replication rate of the cytopathic virus increases viral fitness, and thus the cytopathic virus wins (Figure 1b). These model results are consistent with the arguments made by (Voronin et al. 2005) in the context of in vitro experiments: If the natural death rate of cells is high relative to the virus-induced death rate of infected cells, then the more cytopathic virus, which also replicates faster, is fitter.

Figure 1.

Simulation of the competition dynamics between two virus strain in the absence of immune responses, according to model (1). Strain 1 replicates more slowly and is less cytopathic. Strain 2 replicates faster and is more cytopathic. (a) Competition dynamics assuming a relatively long life span of host cells. In this case, being less cytopathic influences viral fitness significantly, and the mildly cytopathic strain wins. (b) Competition dynamics assuming a relatively short life span of host cells. In this case, the cytopathicity is not an important determinant of viral fitness, and only the replication rate counts. Hence, the more cytopathic but faster replicating strain wins. Parameters were chosen as follows. λ=10, β1=0.2, β2=0.3, a1=0.1, a2=0.6, p=1, c=0.04, b=0.1. For (a) d=0.1; for (b) d=1.

3. The effect of CTL-mediated lysis on the outcome of competition

Here, we add a CTL response to the model and examine how this modulates the competition dynamics. We use one of the simplest CTL models published so far (De Boer and Perelson 1998; Nowak and Bangham 1996), which assumes that CTL proliferate in response to antigenic stimulation, and decay with a slow rate in the absence of antigenic stimulation. The population of CTL is denoted by z. The rate of CTL proliferation is given by cz(y1+y2). In words, upon stimulation by both viruses, the CTL proliferate with a rate c. In the absence of antigenic stimulation, the CTL decay with a rate bz. Finally, the CTL kill infected cells with a rate pyz. Thus, the above model is re-written as follows:

| (2) |

It is important to note that the term used to describe CTL dynamics is over-simplified and in several ways unrealistic. On the other hand, it provides the advantage of analytical simplicity. Therefore, more complex and realistic CTL dynamics equations were explored by numerical simulations, and I found that results were not changed on a qualitative level. Therefore, the simplified model suffices in the current context. Among more complex CTL models, previously published equations were considered which include saturated CTL proliferation (Wodarz and Nowak 2000), as well as programmed CTL division and differentiation pathways (Wodarz and Thomsen 2005). According to the programmed proliferation concept, a single encounter with antigen programs the CTL to undergo a certain number of cell divisions, and to differentiate into effector and memory cells, without the need for further antigenic stimulation. If the infection is still present following this programmed expansion, then the memory cells become repeatedly activated and undergo further rounds of divisions, although exact mechanisms remain to be elucidated. While such a model has different properties during acute infection compared to the model considered here, it has been shown that the properties during a persistent infection, which involves convergence to a steady state, are the same (Wodarz and Thomsen 2005). Since this paper is concerned with SIV, which is a persistent infection that remains at relatively steady states over prolonged periods of time, the conclusions reached here remain robust in such more complex settings. Also, note that the model considered here does not allow the CTL response to drive the virus extinct because it is a deterministic model. Again, this is not a problem in the context of SIV which always persists in the host. For a detailed discussion of different approaches to modeling CTL dynamics, see (Wodarz 2006)

Assume that each virus in isolation can successfully establish an infection. In this case, the CTL response can either become established successfully, or it fails to become established. If the CTL fail to become established, the system reduces to model (1). The condition for the establishment of a CTL response depends on which virus strain is present. If strain 1 is present, then the CTL response invades if cy1* > b. If strain 2 is present, the CTL response invades if cŷ2> b. In the following we assume that both conditions are fulfilled. In this case, the system can converge to one of the following equilibria (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Different outcomes of the competition dynamics between two virus strains in the presence of CTL, according to model (2). Strain 1 replicates more slowly and is less cytopathic. Strain 2 replicates faster and is more cytopathic. (a) Strain 1 out-competes strain 2. (b) Both strains coexist. (c) Strain 2 out-competes strain 1. Parameters were chosen as follows. d=0.1, β1=0.01, β2=0.02, a1=0.1, a2=0.6, p=1, c=0.04, b=0.1. (a) λ = 5; λ = 7; λ = 9.

Virus 1 wins and virus 2 goes extinct. This outcome is described by the following expressions. x(1) = λc/(dc + bβ1), y1(1)=b/c, y2(1) = 0, z(1) = (β1x − d − a1)/p.

Virus 2 wins and virus 1 goes extinct. This is described by x(2) = λc/(dc + bβ2), y1(2) = 0, y2(2)=b/c, z(2) = (β2x − d − a2)/p.

Both virus1 and virus 2 coexist. This is described by the following expressions.

This model and its properties are very similar to those of early ecological models that described the interactions between competing species that were also subject to predation (Butler and Wolkowicz 1986; Caswell 1978). Among other things these studies examined the concept of predator-mediated coexistence of competing species that would otherwise exclude each other. A variety of models with different mathematical formulations was considered in the literature (Butler and Wolkowicz 1986; Caswell 1978), and some of them exhibited various types of oscillating dynamics rather than stable equilibra. Extensive computer simulations of the virus-CTL model considered here indicate that over wide parameter regions, the dynamics involve damped oscillations that converge towards a stable equilibrium (Figure 2). However, there are parameter regions in which sustained limit cycles are observed. The occurrence of the limit cycles does not even require the presence of two virus strains that share the CTL response, they can be observed in the context of simple models that take into account a single virus population and a CTL response. However, we do not concentrate on cycling dynamics here because limit cycles have never been observed in data that document the dynamics of HIV/SIV and specific immune responses. While temporary blips and instabilities in virus load are observed, this is thought to be the result of virus mutations, for instance mutations that allow the escape from immune responses. Therefore, the parameter values which give rise to limit cycle dynamics are likely to be not biologically relevant.

Now, we examine the conditions under which the different equilibirum outcomes are observed. We do this by determining the basic reproductive ratio of an invading virus in the presence of the competing virus strain and its specific immune response. For virus strain 1, this is given by R0(1) = β1x(2)/(d + a1 + pz(2)). For invasion of virus strain 2, this is given by R0(2) = β2x(1)/(d + a2 + pz(1)). The conditions for the outcome of the dynamics are as follows.

Virus 1 wins if R0(1) > 1 and R0(2) < 1.

Virus 2 wins if R0(2) > 1 and R0(1) < 1.

Coexistence is observed if R0(1) > 1 and R0(2) > 1.

As expected, if the CTL response is higher, the basic reproductive ratio of the invading strain is reduced. How much viral cytopathicity influences this measure depends on the magnitude of the rate of virus-induced cell death, a, relative to the rate of CTL-induced cell killing, pz. The rate of virus-induced cell killing, in turn, is given by βx′ − d − a. where x′ is the equilibrium number of uninfected host cells in the presence of the established virus strain and is given by x′ = λc/(dc + bβ). Whether cytopathicity is an important determinant of the ability of a virus to invade or not is therefore dictated by the relative magnitudes of the parameters a and βx′. With this in mind, the basic reproductive ratios given above can be re-written as R0(1) = β1x(2)/(β2x(2)− a2 + a1) and R0(2) = β2x(1)/(β1x(1)− a1 + a2).

It is interesting to consider these expressions in the context of the ability of the CTL response to control the infection. If the CTL response is strong and controls the infection very efficiently, the value of x′ approaches λ/d (i.e. the number of uninfected cells approaches pre-infection levels). Whether viral cytopathicity makes a significant contribution to the ability of the virus to invade depends in this case on the relative magnitude between the values of a and λ/d. If λ/d is of the same order of magnitude as a or lower, then the viral cytopathicity is an important determinant of the ability of the virus to invade. In this case, a sufficient increase in the rate of virus-induced cell killing can be significantly disadvantageous for the virus and result in the inability to invade, despite a faster rate of replication. If the immune system is less efficient, the relevance of the viral cytopathicity for the ability of a virus strain to invade increases. On the other hand, if the value of λ/d is higher relative to the value of a, then the viral cytopathicity is a less significant parameter, and the viral replication rate predominantly determines the growth kinetics, especially in the context of efficient CTL-mediated virus control.

Note that the analysis presented here relies on the equilibrium properties of the model. It was determined whether a second strain can invade an equilibrium between a given virus strain and its specific CTL response. During the asymptomatic phase of the infection, virus load remains relatively stable over time. Changes in population sizes can be observed probably as a result of viral evolution to escape immune responses or to replicate more efficiently. Progression of the infection can thus be viewed as a shifting equilibrium (Nowak and May 2000). The approach taken here assumes that the evolutionary processes considered occur over a time frame during which virus load is relatively stable. If the dynamics are in a phase during which virus load is changing, e.g. as a result of immune escape mutants rising, then this analysis does not apply. In this case, the escape mutant would come to dominate the virus population, rather than mutants with a changed cytopathicity that are still susceptible to the immune responses (this situation would be different if immune escape is directly linked to changes in viral cytopathicity).

In summary, the presence of a CTL response may or may not erase the relevance of the viral cytopathicity for determining whether a virus strain can invade or not. Even if the CTL response is very efficient and controls the virus at low levels, the viral cytopathicity can still remain an important determinant of the ability of the virus to invade. This is because the number of CTL at equilibrium is also determined by host parameters that are not directly related to the CTL response, such as the production and death rates of target cells. What is the situation with HIV infection? I will try to examine this in the next section in the context of parameter estimates derived from the literature.

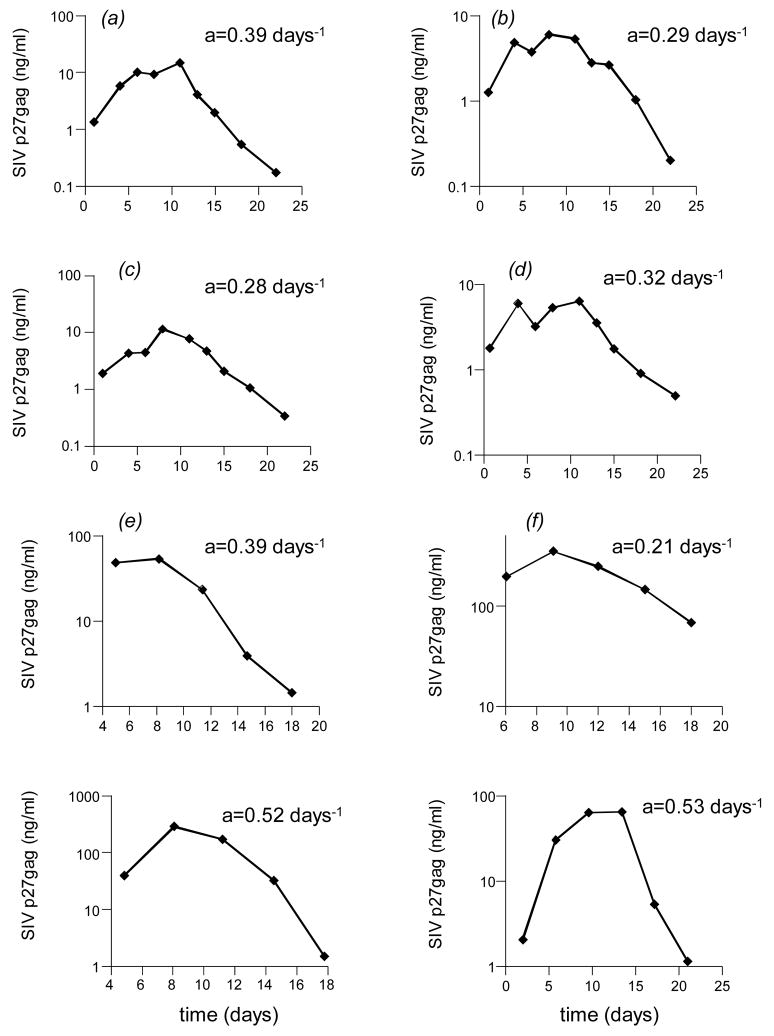

4. SIV dynamics

How do our results apply to SIV infection? According to the data available from the in vitro competition experiments (Voronin et al. 2005), it is hard to estimate parameters of the model. However, parameters have been estimated in SIV infection in general, and this might provide some insights. Animals were infected with SIV, and the infection was allowed to settle around a post-acute steady state (Nowak et al. 1997) (Figure 3a). During this steady state, the level of the virus population changes only little and hence we can assume that βx′ = a + pz′. That is, the rate of new infections equals the rate of cell death (virus + CTL-induced). The animals were treated with the anti-viral drug PMPA and virus load declined exponentially (Figure 3a). The slope of this decline provided an estimate of the death rate of the infected cells (a+pz′), and hence also of the rate of new infections, βx′ (Figure 3a). On average, the result was about βx′ = 0.7 (Nowak et al. 1997). However, these experiments did not provide an estimate of the virus-induced death rate of infected cells, a, because the relative amounts of virus-induced and immune-mediated cell killing could not be distinguished in this study. However, it is possible to obtain a general idea about how fast SIV kills its cells from in vitro experiments in which SIV growth is monitored over time in PBMC (Forte et al. 2003; Ilyinskii and Desrosiers 1996; Reitter and Desrosiers 1998). In such experiments, the virus first grows exponentially to a peak, and then declines exponentially (Figure 3b). If the virus has infected most target cells in the culture by the time when virus load reaches the peak, the subsequent decline of the virus population allows us to determine the death rate of infected cells by measuring the slope of the exponential decay of virus load on a log scale (Figure 3b). This approach was applied to published data. In general it is hard to find studies which document SIV growth in vitro in sufficient detail to measure parameters of a model. Figure 4 lists and plots the data which have been used here to measure the rate of SIV-induced cell death in such experiments. The results from these measurements are quite consistent across different experiments and publications (Forte et al. 2003; Ilyinskii and Desrosiers 1996; Reitter and Desrosiers 1998). The death rate of SIV-infected PBMC in culture tends to be around a=0.3 days−1 (Figure 4) This corresponds to a half life of infected cells which is slightly greater than 2 days. This might be an underestimate if at peak virus load there are still susceptible cells to infect in the culture, thus reducing the subsequent slope of virus decline. In general, however, it is unclear whether such in vitro data correctly reflect the virus-induced death rate of infected cells. On the other hand, in vivo data from macaques infected with single cycle SIV can provide a system in which to estimate the death rate of viruses in the absence of immune responses (Evans et al. 2005). Genetically engineered SIV that is limited to a single cycle of infection was inoculated at high doses into the animals. Virus load peaked at around 4 days post infection and subsequently declined to undetectable levels over the next 4 weeks. CTL did not peak until 2–3 weeks post infection. Thus, the initial decline of the virus population might reflect virus-induced cell death in vivo, without the contribution of immunity. The data from (Evans et al. 2005) are re-plotted in Figure 5, and estimates of viral cytopathicity are given. They range approximately between a=0.3 days−1 and a=0.7 days−1. These values are a little higher than the ones obtained from the in vitro data, but remain in the same general order of magnitude.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the way in which SIV parameters were measured. (a) Measurement of the overall spread rate βx′ using in vivo data. When a monkey is infected with SIV, virus replicates up to a peak during the acute phase and subsequently settles around a post-acute set-point level. While virus stays around this set-point level, the virus population does not grow significantly, and thus βx′ = a + pz′. Drug treatment, indicated by the shaded box, essentially prevents the spread of the virus to new cells, and thus sets β≈0. Consequently, virus decays, and the slope of virus decay on a log axis provides a measure of the death rate of infected cells. This in turn is a composite of the virus- and CTL-mediated death rates (a+pz). Since before therapy, βx′ = a + pz′, this slope also provides a measure of βx′. (b) Measurement of the SIV-induced death rate of infected cells, using in vitro replication of SIV in PBMC. Because in vivo, the virus- and CTL-mediated killing terms cannot be separated from the data, we tried to obtain an estimate of the death rate of infected cells in vitro, in the absence of immunity. While we can expect that the value might differ somewhat from the true in vivo situation, it can provide an estimate of the general order of magnitude. When a culture of PBMC is infected with SIV, the virus grows exponentially with a rate βx0−a, where x0 is the initial number of cells in culture. As the virus approaches peak loads, we can assume that most cells have been infected, i.e. x≈0. Subsequently, the virus decays, and the initial virus decay slope on a log scale can provide an estimate of the virus-induced death rate of infected cells.

Figure 4.

Data on the in vitro replication of SIV in PBMC. Virus load is plotted on a log scale against time. The virus population first increases to a peak, and subsequently declines exponentially. The slope of this decline provides a measure for the virus-induced death rate of SIV-infected cells, a, which is indicated in the plots. The following describes where the data have been taken from. (a) SIVMneCL8 growth in PBMCs from HIV-1 seronegative donors, taken from Fig 1B in (Forte et al. 2003) (b) SIVMneCL8 growth in PBMCs from HIV-1 seronegative donors, taken from Fig 1B in (Forte et al. 2003) (c) SIVMneCL8(35wkSU) growth in PBMCs from HIV-1 seronegative donors, taken from Fig 1C in (Forte et al. 2003) (d) SIVMneCL8(25wkSU) growth in PBMCs from HIV-1 seronegative donors, taken from Fig 1C in (Forte et al. 2003) (e) Growth of SIVmac239 in rhesus PBMC. Taken from Fig 6C in (Reitter and Desrosiers 1998) (f) Growth of SIVmac239 in rhesus PBMC. Taken from Fig 11C in (Reitter and Desrosiers 1998) (g) Growth of SIVmac239 in rhesus PBMC. Taken from Fig 3A in (Ilyinskii and Desrosiers 1996) (h) Growth of SIVmac239 in rhesus PBMC. Taken from Fig 3B in (Ilyinskii and Desrosiers 1996).

Figure 5.

Data from (Evans et al. 2005) that document virus load as a function of time in macaques that were inoculated with a concentrated dose of single cycle SIV (i.e. an engineered SIV strain that is limited to a single cycle of infection). The increase of virus load towards the peak was not documented in the data. Only the subsequent virus decline was documented, and is plotted here. The slope of this decline provides a measure for the virus-induced death rate of SIV-infected cells, a, which is indicated in the plots.

Assuming that the above parameter estimates represent the right order of magnitude, it is possible to ask whether a more virulent virus with both an increased replication rate and an increased cytopathicity will be able to grow in the presence of a competing virus. Assume that the more virulent virus replicates n times as fast and has an m times higher cytopathicity than the less virulent virus. The invasion condition for the virulent virus becomes nβx′ − ma > βx′ − a, where x′ is the equilibrium number of target cells in the presence of the less virulent virus only. The more virulent virus will fail to invade if m > βx′ (n−1)/a + 1. If βx′ = 0.7 (Nowak et al. 1997) and if we set a = 0.4 days−1 (Figure 4 & 5), then the more virulent virus will fail to invade if m > 1.75 (n−1) + 1. In words, if the increase in viral cytopathicity is less than twice the increase in the replication rate.

It is likely that this condition is fulfilled with SIVMneCL8 and SIVMne170. Cell viability assays showed a very significant difference in cytopathicity. Cells were infected with a high multiplicity of infection (MOI, essentially initial amount of virus relative to the number of cells) in culture such that all cells quickly became infected (Voronin et al. 2005). For the early strain SIVMneCL8 only modest cytopathicity was osbserved and cell viability measures never fell below 70%. No exponential decline of the virus population was observed, indicating that infected cells divided faster than they die (Voronin et al. 2005). On the other hand, strong cytopathic effects were observed with the late strain SIVMne170 (Voronin et al. 2005). Once all cells in culture became infected after a few days, the number of life cells decreased exponentially with a half life of about 1 day, until most cells in the culture were dead. This indicates that this virus is highly cytopathic. On the other hand, such differences were not observed in the replication rate of the two viruses. In the competition experiments with an unlimited life span of cells, the relative frequency of the two virus strains remained constant during the initial growth phase, and the early strain SIVMneCL8 only started to increase in relative frequency once most target cells were infected (Voronin et al. 2005). If there was a significant difference in the replication rate between these two virus strains, the faster strain would have increased in relative frequency already during the initial growth phase in the experiment. Note that I do not argue that these two strains must have the same replication rate; based on other data that document growth kinetics of these two strains it is likely that the more cytopathic strain replicates somewhat faster, especially in vivo. However, these data indicate that the difference between the two strains in the viral cytopathicity is significantly larger than the difference in the viral replication rate. This means that the CTL response might not be the driving force that accounts for the emergence of the cytopathic strain SIVMne170 during later stages of the infection. This raises the questions of why the cytopathic strain emerges and invades late in the disease course.

One possibility would be that the real reason for the emergence of this strain is that it has escaped immune responses. For this to be true, the escape mutation must render the virus more cytopathic. While the increased cytopathicity would confer a disadvantage to this virus strain, the escape from immune responses would outweigh this cost, resulting in a rise of this strain. Data indicate that late stage variants have escaped immune responses (Kimata et al. 1999). When they are infected into a new animal, they establish significantly higher set point virus loads than early stage variants, and consequently induce faster disease progression in the new animals. Establishment of high set point virus load and fast progression correlated with the inability of the host animal to mount neutralizing antibodies to the infecting virus in this study. However, it is unclear whether the mutation that leads to immune escape also renders the virus more cytopathic. Another possibility is that the standard virus dynamics assumptions considered here do not entirely apply. It has recently been shown that multiple virus particles can infect the same cell, a process called coinfection (Levy et al. 2004). Ecological theory (Nowak and May 1994), and a mathematical application of this to HIV dynamics (Wodarz and Levy submitted), indicates that coinfection can result in the emergence of virus strains with a reduced basic reproductive ratio. These strains can coexist with viruses characterized by a higher basic reproductive ratio. It is intriguing to consider the hypothesis that coinfection is required for the emergence of cytopathic viruses that cause the onset of AIDS, and this has also implications for understanding SIV dynamics in naturally infected monkeys that never develop AIDS (Broussard et al. 2001; Goldstein et al. 2000; Silvestri et al. 2003).

5. Discussion and Conclusion

In a set of basic in vitro experiments, it was shown that a more cytopathic SIV strain, isolated late during the infection process, lost in competition experiments to a less cytopathic virus strain, isolated earlier during the infection process. In a second set of experiments, the background death rate of the target cells was artificially reduced. In this case, the more cytopathic late strain outcompeted the less cytopathic early strain because the rate of virus-induced cell death was small compared to the background rate of cell death. It was argued that the latter scenario better reflects the in vivo environment where CTL kill infected cells, and that this could explain why the cytopathic viruses emerge during the later stages of the infection. Here, mathematical models were used to examine how the presence of CTL responses influences the effect of viral cytopathicity on the replicative fitness of the virus. Depending on the parameter values of the system, viral cytopathicity may or may not be an important determinant of viral fitness in the presence of CTL. Importantly, there is no clear correlation between the relevance of viral cytopathicity and the ability of the CTL response to control the infection. Even in the presence of very efficient CTL-mediated virus control, viral cytopathicity can still be a major determinant of viral fitness. The reason is that according to the model, the number of CTL is determined by host parameters that are not directly related to the immune system, such as the natural production and death rates of target cells.

Using published data from SIV infection in vitro and in vivo, an attempt was made to parameterize the model in order to get more insights into whether CTL responses could confer a selective advantage to the late stage and cytopathic virus SIVMne170. The calculations indicate that the presence of specific CTL responses might not lead to the selection of the cytopathic SIV strain late in the infection process. This assumes that the property of cytopathicity is not directly linked to an immune escape phenotype. Therefore, the analysis presented here raises the possibility that the in vitro experiment, where the general background death rate of target cells was artificially increased (Voronin et al. 2005), does not explain why the cytopathic strain SIVMne170 arises during the later stages of the infection. Having said this, I would like to point out that while the parameter estimates are a useful guide, they have been obtained from previously published data that were not specifically geared towards answering the questions examined here. Therefore, more detailed experimental and computational work should be done to examine parameter estimates more closely. However, the reasoning presented here is further supported by the fact that reducing the level of virus control results in viral cytopathicity having a higher impact on viral fitness. During the initial stages of HIV infection, after the acute phase, anti-viral immunity is strongest and virus load is lowest. The degree of immune-mediated virus control declines over time as the disease progresses. Therefore, if the cytopathic virus does not invade in the presence of an efficient CTL response that controls SIV replication during the earlier stages of the infection, it certainly cannot invade once the immune response has weakened during later stages of the infection. If these arguments are true, then the data presented by (Voronin et al. 2005) indicate that SIV strains with a reduced basic reproductive ratio emerge during disease progression, requiring more complex evolutionary explanations. As mentioned above, the ability of multiple HIV particles to infect the same cell (coinfection) could account for the rise of the cytopathic strain during the later stages of the infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH grant 1R01AI058153-01A2. The author thanks Jeff Lifson for very helpful comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson RM, May RM. Coevolution of hosts and parasites. Parasitology. 1982;85 (Pt 2):411–26. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000055360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RM, May RM. Infectious diseases of humans. Oxofrd, England: Oxfors University Press; 1991 . [Google Scholar]

- Broussard SR, Staprans SI, White R, Whitehead EM, Feinberg MB, Allan JS. Simian immunodeficiency virus replicates to high levels in naturally infected African green monkeys without inducing immunologic or neurologic disease. J Virol. 2001;75:2262–75. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2262-2275.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler GJ, Wolkowicz GSK. Predator-mediated competition in the chemostat. J Math Biol. 1986;24:167–191. [Google Scholar]

- Caswell H. Predator-mediated coexistence: a non-equilibrium model. The American Naturalist. 1978;112:127–154. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer RJ, Perelson AS. Target cell limited and immune control models of HIV infection: a comparison. J Theor Biol. 1998;190:201–14. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1997.0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D, Herre EA. The evolution of parasitic diseases. Parasitol Today. 1996;12:96–101. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(96)80668-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D, Mangin KL. The influence of host demography on the evolution of virulence of a microsporidian gut parasite. Evolution. 1997;51:1828–1837. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb05106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DT, Bricker JE, Sanford HB, Lang S, Carville A, Richardson BA, Piatak M, Jr, Lifson JD, Mansfield KG, Desrosiers RC. Immunization of macaques with single-cycle simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) stimulates diverse virus-specific immune responses and reduces viral loads after challenge with SIVmac239. J Virol. 2005;79:7707–20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7707-7720.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forte S, Harmon ME, Pineda MJ, Overbaugh J. Early- and intermediate-stage variants of simian immunodeficiency virus replicate efficiently in cells lacking CCR5. J Virol. 2003;77:9723–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9723-9727.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank SA. Models of parasite virulence. Q Rev Biol. 1996;71:37–78. doi: 10.1086/419267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein S, Ourmanov I, Brown CR, Beer BE, Elkins WR, Plishka R, Buckler-White A, Hirsch VM. Wide range of viral load in healthy african green monkeys naturally infected with simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2000;74:11744–53. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11744-11753.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilyinskii PO, Desrosiers RC. Efficient transcription and replication of simian immunodeficiency virus in the absence of NF-kappaB and Sp1 binding elements. J Virol. 1996;70:3118–26. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3118-3126.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata JT. HIV-1 fitness and disease progression: insights from the SIV-macaque model. Curr HIV Res. 2006;4:65–77. doi: 10.2174/157016206775197628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata JT, Kuller L, Anderson DB, Dailey P, Overbaugh J. Emerging cytopathic and antigenic simian immunodeficiency virus variants influence AIDS progression. Nat Med. 1999;5:535–41. doi: 10.1038/8414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata JT, Overbaugh J. The cytopathicity of a simian immunodeficiency virus Mne variant is determined by mutations in Gag and Env. J Virol. 1997;71:7629–39. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7629-7639.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DN, Aldrovandi GM, Kutsch O, Shaw GM. Dynamics of HIV-1 recombination in its natural target cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4204–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306764101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak MA, Bangham CR. Population dynamics of immune responses to persistent viruses. Science. 1996;272:74–9. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak MA, Lloyd AL, Vasquez GM, Wiltrout TA, Wahl LM, Bischofberger N, Williams J, Kinter A, Fauci AS, Hirsch VM, Lifson JD. Viral dynamics of primary viremia and antiretroviral therapy in simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 1997;71:7518–25. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7518-7525.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak MA, May RM. Superinfection and the evolution of parasite virulence. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1994;255:81–9. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak MA, May RM. Mathematical principles of immunology and virology. Oxford University Press; 2000 . Virus dynamics. [Google Scholar]

- Perelson AS. Modelling viral and immune system dynamics. Nature Rev Immunol. 2002;2:28–36. doi: 10.1038/nri700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitter JN, Desrosiers RC. Identification of replication-competent strains of simian immunodeficiency virus lacking multiple attachment sites for N-linked carbohydrates in variable regions 1 and 2 of the surface envelope protein. J Virol. 1998;72:5399–407. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5399-5407.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestri G, Sodora DL, Koup RA, Paiardini M, O’Neil SP, McClure HM, Staprans SI, Feinberg MB. Nonpathogenic SIV infection of sooty mangabeys is characterized by limited bystander immunopathology despite chronic high-level viremia. Immunity. 2003;18:441–52. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veazey RS, DeMaria M, Chalifoux LV, Shvetz DE, Pauley DR, Knight HL, Rosenzweig M, Johnson RP, Desrosiers RC, Lackner AA. Gastrointestinal tract as a major site of CD4+ T cell depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. Science. 1998;280:427–31. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voronin Y, Overbaugh J, Emerman M. Simian immunodeficiency virus variants that differ in pathogenicity differ in fitness under rapid cell turnover conditions. J Virol. 2005;79:15091–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15091-15098.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wodarz D. Killer cell dynamics: mathematical and computational approaches to immunology. New York: Springer; 2006 . [Google Scholar]

- Wodarz D, Nowak MA. Immune responses and viral phenotype: do replication rate and cytopathogenicity influence virus load? Journal of Theoretical Medicine. 2000;2:113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Wodarz D, Thomsen AR. Effect of the CTL proliferation program on virus dynamics. Int Immunol. 2005;17:1269–76. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]