Abstract

Big Potassium (BK) ion channels have several splice variants. One splice variant initially described within human glioma cells is called the glioma BK channel (gBK). Using a gBK-specific antibody, we detected gBK within three human small cell lung cancer (SCLC) lines. Electrophysiology revealed that functional membrane channels were found on the SCLC cells. Prolonged exposure to BK channel activators caused the SCLC cells to swell within 20 minutes and resulted in their death within five hours. Transduction of BK-negative HEK cells with gBK produced functional gBK channels. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis using primers specific for gBK, but not with a lung-specific marker, Sox11, confirmed that advanced, late-stage human SCLC tissues strongly expressed gBK mRNA. Normal human lung tissue and early, lower stage SCLC resected tissues very weakly expressed this transcript. Immunofluorescence using the anti-gBK antibody confirmed that SCLC cells taken at the time of the autopsy intensely displayed this protein. gBK may represent a late-stage marker for SCLC. HLA-A*0201 restricted human CTL were generated in vitro using gBK peptide pulsed dendritic cells. The exposure of SCLC cells to interferon-γ (IFN-γ) increased the expression of HLA; these treated cells were killed by the CTL better than non-IFN-γ treated cells even though the IFN-γ treated SCLC cells displayed diminished gBK protein expression. Prolonged incubation with recombinant IFN-γ slowed the in vitro growth and prevented transmigration of the SCLC cells, suggesting IFN-γ might inhibit tumor growth in vivo. Immunotherapy targeting gBK might impede advancement to the terminal stage of SCLC via two pathways.

Keywords: Small cell lung cancer, BK ion channel, glioma BK ion channel, real time PCR, CTLs, interferon-γ

Introduction

Immunotherapy of malignant tumors has improved patient survival with some cancers. Recent examples include FDA approved treatment for castrate resistant prostate cancer patients using “Provenge”, which targets a prostate-specific antigen via dendritic cells (DC) to stimulate the host T cells [1]. Encouragingly, DC-based vaccines are also improving the survival of patients with Glioblastoma Multiforme [2], and in some lung cancers (reviewed in [3]). The success of these vaccines is due to the actions of the potent antigen-presentation cells, namely DC, to stimulate the host’s own T cells to recognize the autologous tumor antigens. These activated T cells seek out the remaining tumor cells and eliminate them. This approach is dependent on finding appropriate tumor antigen(s) that will elicit a cytotoxic T cell response. Further, targeting a key cancer cell function may prove more cytoreductive than using any ordinary tumor antigen as evidenced by the success with the herceptin antibody, which interferes with an obligatory growth factor signaling pathway, while simultaneously permitting antibody dependent cytotoxicity to occur [4].

Big Potassium (BK) channels are over-expressed by malignant glioma cells [5-8]. A splice variant of the BK channel, called the glioma Big Potassium (gBK) channel, was initially described in human gliomas; hence its utilitarian name [9]. Our recent work with human glioma cells identified two epitopes within the gBK channel that could induce human cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) [10]. BK channel expression is nearly universal in every cell throughout the body and helps play an important role in normal ionic concentration homeostasis, while gBK manifestation is much more tumor-specific [9,10]. The gBK isoform contains an additional 33 amino acids inserted only within the intracellular region of the hbr5 isoform (hbr5 has an additional 29 amino acid insert) of the basic BKα chain. gBK are only highly expressed within cancer cells. Three putative binding sites [9] within the gBK region (casein kinase IIα, protein kinase C and calmodulin dependent kinase II) may provide the cancer cell with altered biochemical processes, distinct from normal BK channel properties. Gliomas are highly invasive tumors, and this characteristic makes them difficult to treat. All medical interventions currently allow the escape of a few glioma cells that later initiate the recurrence. Ion channels provide a possible mechanism by which cancer cells can squeeze through tight spaces of its surrounding environment [11,12]. While at rest and in homeostasis, the cancer cell maintains its balanced physiological ionic composition, which is a high intracellular level of K+ ions, with concurrent lower concentrations of Na+, Ca+2, Cl- ions and water. When there is a change to the environment, a disruption of normal ionic homeostasis can occur at the leading edge of the cell. When the potassium channels such as gBK and BK are activated and internal K+ ions are released, Na+ replaces the K+ cations. As Na+ cations enter, so do Cl- anions and water, hence the cell can swell at the tip and create the osmotic forces that assist the rest of the cell to pull itself through the normal tissue. BK channels are described as being mechano-sensitive ion channels, where membrane proteins are responding to mechanical stimuli, such as membrane stretching these channels are activated [13]; i.e. K+ release. Ionizing radiation of human T98G and U87 glioma cells directly activates BK channels and makes these cells more invasive [14]; this provides further support that BK ion channels play an active role in cancer cell migration.

Small cell lung cancers (SCLC) are derived from the “Kulchitsky” neuroendocrine/epithelial cells [15,16]. Similar to gliomas, SCLC is very invasive [16,17]. SCLC cells may share common biochemical and motility processes involving gBK like they are thought to occur with glioma cells. With 3 SCLC lines, we showed that gBK is present within these cells using a gBK-specific antibody. Cell-surface patch clamping revealed functional gBK channels on the HTB-119 SCLC cells. These BK ion channels proved to be physiologically functional, in that BK channel activators caused all the SCLC cells to swell within 20 minutes and ultimately die after five hours of prolonged BK channel activation. To prove the gBK isoform was functional, the gBK gene was stably transduced into BK channel-negative HEK cells and these cells responded to BK channel activators and demonstrated identical electrophysiological tracings characteristic of BK channel. We further observed that SCLC autopsy specimens displayed very high gBK expression levels by quantitative reverse transcriptase-real time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) compared to those SCLC taken from initial surgical resections or from noncancerous lung samples. When clinical SCLC samples were immuno-stained with anti-gBK channel specific antibody, we confirmed that SCLC cases taken at the autopsy possessed high levels of gBK proteins, whereas the SCLC at the initial time of diagnosis had minimal gBK protein expression. CTLs that were generated towards the two gBK specific epitopes killed SCLC cell lines, which were both gBK+ and HLA-A2+. These effector cells failed to kill human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells that were HLA-A2+, but gBK negative. The addition of recombinant interferon-γ (IFN-γ) caused the SCLC cells to up-regulate MHC class I protein, while concomitantly inhibiting the expression of gBK. The continued exposure to IFN-γ slowed the growth of SCLC cells in vitro. Recombinant IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor and iberiotoxin prevented the SCLC cells from migrating through 5 micron pores. The gBK antigen may provide a unique target antigen that will prevent progression from early to late-stage disease. Targeting this tumor antigen after the initial radiation and chemotherapy may prolong patient survival by an active immunotherapy strategy. In non-small cell lung cancer COX2 inhibitors and irradiated tumor cells generated significantly more IFN-γ producing T cells, and enhanced the immune response towards those lung cancers [18]. Therefore, a passive immunotherapy strategy using adoptive transfer of in vitro sensitized CTL in combination with checkpoint inhibitors could slow SCLC cell growth in vivo. So finding appropriate late stage tumor antigens might be quite valuable.

Experimental procedures

Cell lines

Three SCLC cell lines, HTB-119, HTB-180, and H1436 [NCI-H69, NCI-H345, and NCI-H1436, respectively] were obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). These three cell lines were selected, since prior literature reported these cells were HLA-A2-positive [19,20]. Human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells [also HLA-A2+, 10] were obtained from Dr. Michael Myers (California State University, Long Beach, CA).

Antibody based analyses

The goat polyclonal antibody directed towards human gBK was made by GenScript Inc. (Piscataway, NJ) [10]. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics test was used to show significant differences (P<0.05) between antibody staining of the isotypic control and the various cell lines by flow cytometry.

VAMC-LB archived paraffin blocks of SCLC, either from the initial surgical or autopsy specimens were sectioned. Four normal lung samples without any cancer, two specimens from newly diagnosed SCLC (Stage I) and six specimens (Stage IV) from autopsy cases were examined by immunofluorescent staining using the anti-gBK antibody staining. The intensity of the fluorescent signal was averaged from 3 representative and separate fields. The cumulative amount of the fluorescence from each field of the three conditions was then calculated and data is presented as the average and standard deviation of the replicates.

Patch clamping techniques

Cells were plated onto glass coverslips coated with poly-L-lysine and washed twice with phosphate buffered saline as described previously [21].

A whole-cell configuration was achieved and currents were measured at room temperature (20-25°C). The holding potential in all patches was -80 mV. For drug testing, the whole-cell patch was pulsed with 30 mV or 120 mV test potential for 50-100 ms every 10 s [22]. A syringe-driven perfusion system was applied to completely exchange the bath solution. Pimaric acid (PiMA) was purchased from Alomone Labs (Jerusalem, Israel) and paxilline was bought from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MI).

Tumor tissue

IRB approval from the VALBMC was granted for this project before its initiation. We collected either autopsy material or remnant surgical material not needed for diagnostic purposes. Surgical material was collected only after informed consent was given. Next of kin signed the autopsy consent forms which allow scientific investigations. We purchased 8 surgical SCLC cases from Oncomatrix, (San Diego, CA), who obtained their tissues from Eastern Europe, where they still surgically resect SCLC patients. The stages of these surgical patients were: three-Stage IA, one-Stage IB, three-Stage IIIA and two-Stage IIIB. The three autopsy samples from our SCLC cases (Stage IV, all patients had multiple (>5) distant metastases documented), along with three lung samples taken at autopsy from individuals who did not have lung cancer were derived from the VAMC and analyzed. All the autopsy samples were acquired within 24 hrs of the patient’s demise. All the specimens were first mechanically homogenized and the RNA was extracted with Trizol. The quality of the RNA was first assessed by a 260/280 ratio of >1.9. The amount of the 18S RNA was assessed; all samples had identical amounts to assure no biases occurred in the results obtained between the autopsy and surgical samples.

Polymerase chain analysis

Quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was done as previously described [23,24]. The sequences of the primers used were: gBK Forward: 5’-CGTTGGGAAGAAC ATTGTTC-3’; gBK Reverse: 5’-AACTGGCTCGGTCACA AG-3’ to identify the gBK/hbr5 region within the gBK transcripts. Sox 11 Forward: 5’-GTAGTGGTGA TGATGATGATG-3’ and Sox11 Reverse: 5’-GCGTCACGACATCT TATC-3’. 18S RNA Forward and 18S Reverse were 5’-CAGGATTGACAGATTGATAGC TCT-3’ and Reverse-5’-GAGTCTCGTTCGT TATCGGAATTA-3’, respectively.

To determine the size of the BK amplicons, the cDNA from the lung tissue was analyzed by 35 cycles of amplification using the primers to detect the 5’ and 3’ flanking regions of the BK native channel. The primers were: Forward: 5’-GACATCACAGATCCCAAAAG-3’ Reverse: 5’-GTGTTGACGGCTGCTCATC-3’. If the PCR products contained both the gBK region and hbr5 region, the PCR product was 253 bps; if the PCR amplicon contained the hbr5 and no gBK region, the PCR product size was 157 bps. If the PCR product size was 67 bps then the PCR products did not contain gBK and hbr5. The amplicons were then run on a 2% agarose gel and then stained with ethidium bromide and viewed under the UV transilluminator and photographed with the ChemiDoc MP workstation (BioRad, Hercules, CA). The densitometric reading was calculated using the Un-Scan-It Software (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT).

Cloning of gBK cDNA and transfection

gBK cDNA was initially cloned into the plasmid pcDNA3.1 [10]. The gBK and the wild type BK sequences were engineered into the lentiviral vector, pLNCX2 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). The pLNCX2/gBK plasmid was transfected into the packaging cell line PT67 (Clontech) using Xfect Transfection Reagent from Clontech. After transfection, the cells were cultured in DMEM containing 1 mg/ml G418 (Gemini Bioproducts, West Sacramento, CA). The supernatant was harvested and transduced into HEK cells. The gBK expression was confirmed by using qRT-PCR using gBK specific primers and flow cytometry using gBK specific antibody. After the gBK was transduced into HEK cells, the same cells were co-transduced with the wild type BK to model the SCLC cells which have both gBK and BK expression.

Generation of human CTL

The first type of CTL effector populations generated for this study were tumor associated antigen-directed, gBK-specific CTL. The anti-gBK CTL were generated by lymphocyte dendritic cell reactions using PBMC responder and gBK peptide-pulsed, DC stimulator cells from the same A*0201+ individual [10].

The second type of CTL effector populations generated were alloreactive CTL. PBMC from two different HLA-A*0201+ individuals, but otherwise HLA-mismatched, served as responders in one-way mixed lymphocyte reactions. Inactivated stimulator cells were PBMC from an individual who was also HLA-A*0201+ but mismatched at HLA-A*30, -B*72, -B*61, -C*2, and -C*10. Thus, the alloresponsive CTL would target these latter class 1 antigens.

Cytotoxicity data from quadruplicate cultures at each effector to tumor target cell ratio (E:T) is presented as mean specific killing ± standard deviation as previously described [10,23]. The HLA-A*30+ individual who served as a source of stimulator cells to make alloreactive CTL, also supplied PBMC that were nonspecifically-activated with PHA and interleukin-2. The resulting lymphoblasts served as targets (positive control) in the cytotoxicity assays. Values were considered significantly different, if P<0.05 was achieved using the Student’s t test.

Cell proliferation assay

The SCLC proliferation assay was performed using the PrestoBlueTM Cell Viability Reagent (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Ten thousand cells were added to each well of a 96-well plate. Afterwards, the plate was analyzed using the NOVOStar fluorescence plate reader BMG LABTECH Inc. (Cary, NC). Cell numbers were then calculated accordingly.

Transmigration studies

The Chemo-Tx disposable chemotaxis system with 5 μm pores from NeuroProbe (Gaithersburg, MD) were used according to the manufacturer’s directions. Twenty thousand SCLC cells in PBS were loaded in the top chamber with either PBS alone, 0.05 μM iberiotoxin, 10 ng/ml rhIFN-γ, or 10 ng/ml rhTNF-α. The bottom chamber contained 100 ng/ml of recombinant interleukin-6 to induce SCLC transmigration [25]. The human cytokines were purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). The number of cells transmigrating from the upper to lower chambers after an overnight incubation (18 hrs) was determined in octuplicate replicates. Fluorescent cells at the bottom of the wells in the 96 well plates were determined by the NOVOStar plate reader. A student’s t test was then used to verify significant differences (P<0.05) occurred between the experimental groupings from the control.

Results

gBK protein expression within SCLC cell lines

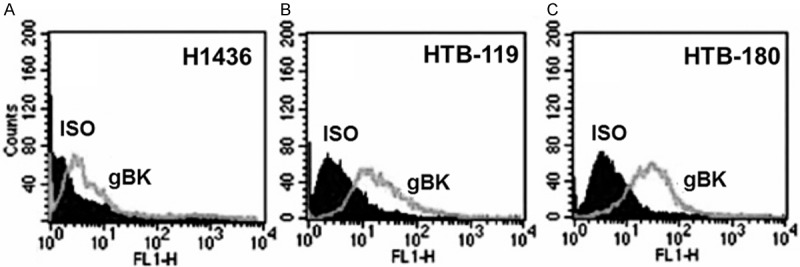

gBK was initially described within high-grade human gliomas, but it was also found in many other cancers [9,10]. SCLC is thought to originate from neuro-endocrine precursor cells (Kulshitsky cells). SCLC are also highly invasive [15,16]. We hypothesized that gBK would also be highly expressed in SCLC, too. Three SCLC cell lines, H1436, HTB-119, and HTB-180 were tested to determine whether the gBK protein was detected. The exponentially growing cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained with a gBK specific antibody that we previously used [10]. All the SCLC cell lines expressed gBK (Figure 1A-C). H1436 displayed the least, while HTB-180 possessed the greatest amount of gBK of the three SCLC cell lines tested. These results allowed us to do functional studies with the SCLC in vitro.

Figure 1.

gBK-specific antibody detects gBK within 3 human SCLC cell lines. The three gBK protein profiles of the SCLC cells (H1436, HTB-119 and HTB-180) were analyzed by using intracellular flow cytometry (Panels A-C respectively). Flow cytometric analysis of 104 cells is shown. The gBK expression is displayed by the gray line while the isotypic control (ISO) is shown as the dark shaded region.

Functional membrane BK channels are present at the plasma membrane of SCLC

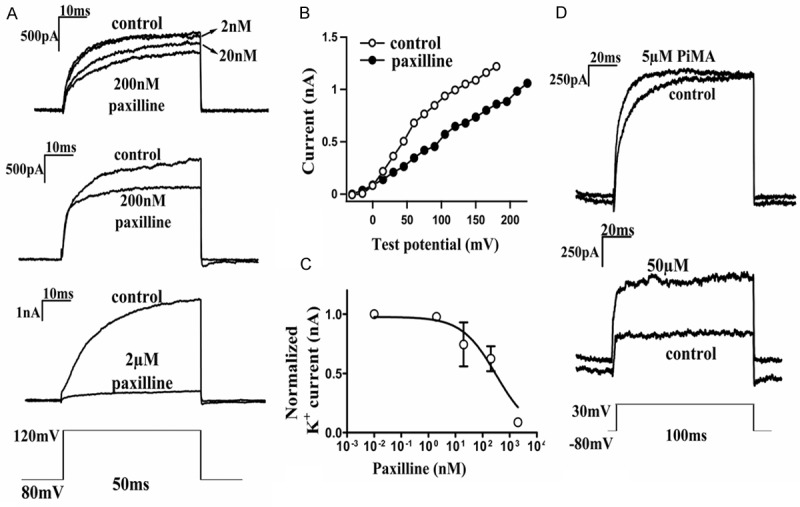

The cell line HTB-119 was used to test the presence of functional BK channels by whole-cell patch-clamping techniques. Applying a test potential of 30 mV or 120 mV to the voltage-clamped SCLC induced whole-cell K+ currents consistent with known properties of BK channels [22]. The perfusion of paxilline induced a dose-dependent block of the K+ currents (Figure 2A-C), consistent with the known electrophysical properties of BK channels. A currentvoltage (I-V) plot generated from the stable region of K+ current traces from the patches treated with 200 nM paxilline showed a strong reduction in the currents at the higher voltages (Figure 2B). Plotting normalized currents showed a half-maximal block of the K+ current expressed by the HTB-119 cells with a value of 313 ± 145 nM. A dose-dependent opening of K+ current was observed upon stimulation with various doses of a specific BK channel activator, pimaric acid (PiMA) (Figure 2D). Thus, functional BK channels are present on the membranes of the SCLC cells.

Figure 2.

Functional Big Potassium (BK) channel currents of HTB-119 SCLC cells, as documented by electrophysiology. The HTB-119 cells were plated on glass coverslips and paxilline was added after a stable whole-cell configuration was achieved. Panel A shows the: The active blockage of BK current by various doses of paxilline (2, 20, or 200 nM) with 50 ms pulses at 120 mV test potential. Panel B: Illustrates the current-voltage plot generated from the stable region of BK current traces, with and without 200 nM paxilline treatment. Panel C: Plots the dose-dependent blockage of BK current by paxilline treatment. Panel D: Represents the effect of various doses of pimaric acid (5 or 50 μM) on the opening of the BK current with various doses of pimaric acid treatment (5 or 50 μM) with pulses at 30 mV for 100 ms.

SCLC cells swell in response to the specific BK channel activator, pimaric acid, which kills the SCLC cells

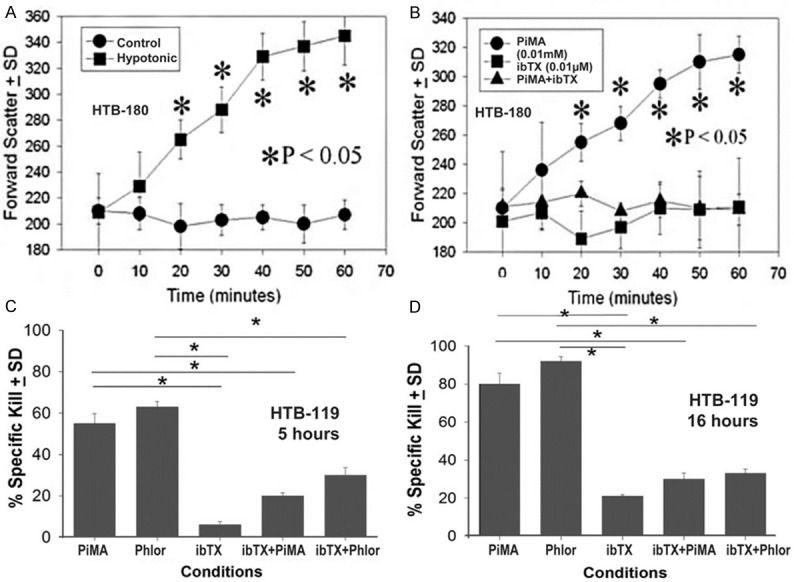

In vitro cell swelling assays were next performed with PiMA (Figure 3) using the flow cytometer’s sensitive forward scatter detector to measure changes in cell size. All three SCLC cells were analyzed this way and showed identical results. The cells were exposed to a hypotonic solution (0.9X PBS) as a positive control, and those cultured in a1X PBS solution were used as a negative control. HTB-180 cells were exposed to these agents and the cells were analyzed at 10-minute intervals for one hour. As shown in Figure 3A, all values induced by hypotonic PBS incubation at 20 minutes or later were statistically different from the comparable control values. After 20 minutes of exposure to PiMA, cell swelling occurred and was considerably elevated above baseline values observed at Time 0 (Figure 3B). During this assay, additional experiments were performed in which r-iberiotoxin (iberio), a specific BK channel inhibitor, was added to the cultures for specific blocking of the BK channel-induced swelling. When iberiotoxin was added to the SCLC cells (Figure 3B) no swelling occurred, but iberiotoxin’s presence significantly antagonized the swelling induced by pimaric acid.

Figure 3.

BK channel activators induce cell swelling and cell death by 5 hrs in SCLC cells. HTB-180 cells in single cell suspensions were incubated with hypotonic PBS (0.9X PBS), 0.01 mM pimaric acid (PiMA), phloretin (Phlor) or 0.01 μM recombinant iberiotoxin (ibTX) at 37°C. At timed intervals, the samples 104 cells were analyzed on the flow cytometer’s forward scatter detector. (Panel A) Shows the time kinetics with hypotonic PBS; (Panel B) Shows the: inhibitory effect of ibTX (0.01 μM) preventing cell swelling in response to pimaric acid, a BK channel activator (0.01 mM PiMA). The asterisks indicate a significant difference (P<0.05) between the treated cells and their respective controls. Each point represents the values of 10,000 cells. (Panel C) Cytotoxicity after 5 hours and (Panel D) Shows the cytotoxicity after 16 hrs. One million Cr51 labeled HTB-119 SCLC cells were incubated with 0.01 mM pimaric acid (PiMA), 1.0 mM phloretin (Phlor), 0.01 μM recombinant iberiotoxin (ibTX), or 0.01 PiMA and 0.01 μM iber, 0.1 μM (ibTX), and 1.0 mM (Phlor) and 0.01 μM ibTX. Data shown at the indicated times show the percentage of specific release ± standard deviation of triplicate cultures. The asterisks indicate significant differences (P<0.05) between the experimental and their respective controls as indicated by the various lines.

Next, we showed that prolonged BK channel activation killed the SCLC cells like we earlier observed with human glioma cell lines [26,27]. SCLC cells labeled with 51Cr were allowed to incubate 5 or 16 hours with various BK channel activators or inhibitors. Figure 3C shows the typical killing response that we observed with HTB-119 cells after 5 hrs of exposure to the activators and/or inhibitors. PiMA and phloretin (phlor; another BK channel opener) significantly killed these cells starting at five hours. Cytotoxicity was further enhanced at 16 hours (Figure 3D), compared to cells incubated in the presence of iberiotoxin alone. When iberiotoxin was co-incubated with either pimaric acid or phloretin, the killing of the SCLC cells was significantly reduced (P<0.05). Similar responses were recorded for HTB-180 or H1436 cells (data not shown).

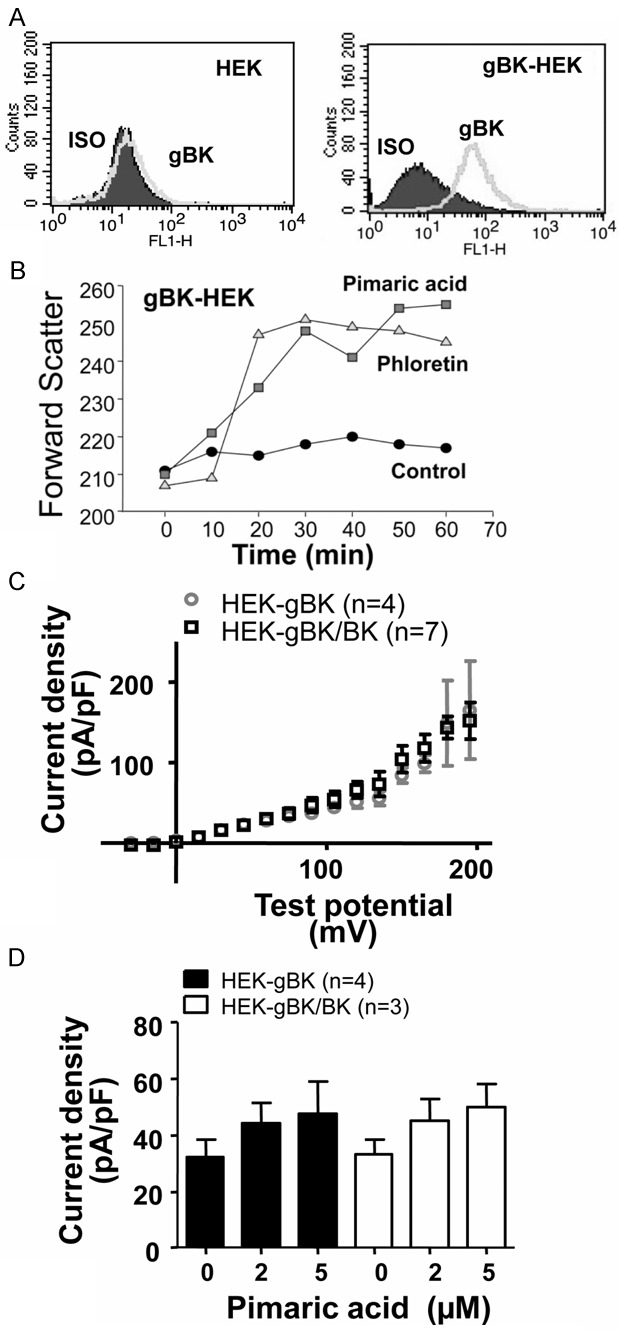

gBK transduced into HEK induces functional channels

The previous experiments (Figures 2 and 3) suggest, but do not prove conclusively that gBK is functional within the SCLC cells. The possibility exists that the more abundant gBK could be non-functional, while the fewer remaining BK channels could mediate those functional effects of the BK activators. To date there are no chemical inhibitors which can discriminate between BK and gBK. Likewise it is impossible to specifically knock-down or silence BK without affecting gBK. To prove that gBK are functional ion channels, we genetically cloned the gBK isoform and stably transduced human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells. HEK cells do not express BK channels [22]. Figure 4A, Right Panel shows the flow cytometric profile of gBK transduced HEK cells with regards to anti-gBK staining, while the Left Panel shows negligible gBK staining of the empty viral vector transduced HEK cells. The gBK transduced HEK cells swelled when exposed to either pimaric acid or phloretin (Figure 4B). Figure 4C shows the current-voltage plot of both the gBK and co-gBK/BK transduced HEK cells. Identical currents were produced when both cell lines were tested from the -40 mV to 120 mV test range. Figure 4D illustrates that an ion flux current density (pA/pF) occurred during whole cell configuration using the HEK-gBK and HEK-gBK/BK co-transduced cells. This ion flux was recorded when the exposed membrane was activated by various concentrations of pimaric acid in a dose-dependent manner. Thus, the HEK cells transduced by gBK appear to have the same functional properties as HEK cells possessing the wild type BK channel.

Figure 4.

qRT Functional gBK is found in HEK cells transduced with gBK. BK and gBK negative HEK cells were stably transduced with the gBK gene. Panel A: The i.c. flow cytometry demonstrating the presence of gBK on the gBK transduced HEK cells (Right Panel) and in empty vector transduced HEK (Left). Panel B: Cell swelling of these gBK-HEK cells upon incubation with either pimaric acid (0.01 mM) or phloretin (1.0 mM) over 60 minutes period of incubation. Electrophysiological tracings of gBK-HEK cells were compared to the HEK cells that were co-transduced with both gBK and BK. Panel C: HEK-gBK (n=4) and HEK-gBK/BK (n=7) showed similar current density (pA/pF) vs. voltage profile during whole cell configuration. Whole cell K+ currents were elicited by applying test potential of -15 to 195 mV with 15 mV increments. Panel D: Pimaric acid showed similar channel opening in both HEK-gBK (n=4) and HEK-gBK/BK (n=3) cells when pulsed with 30 mV for 50 ms every 30 s.

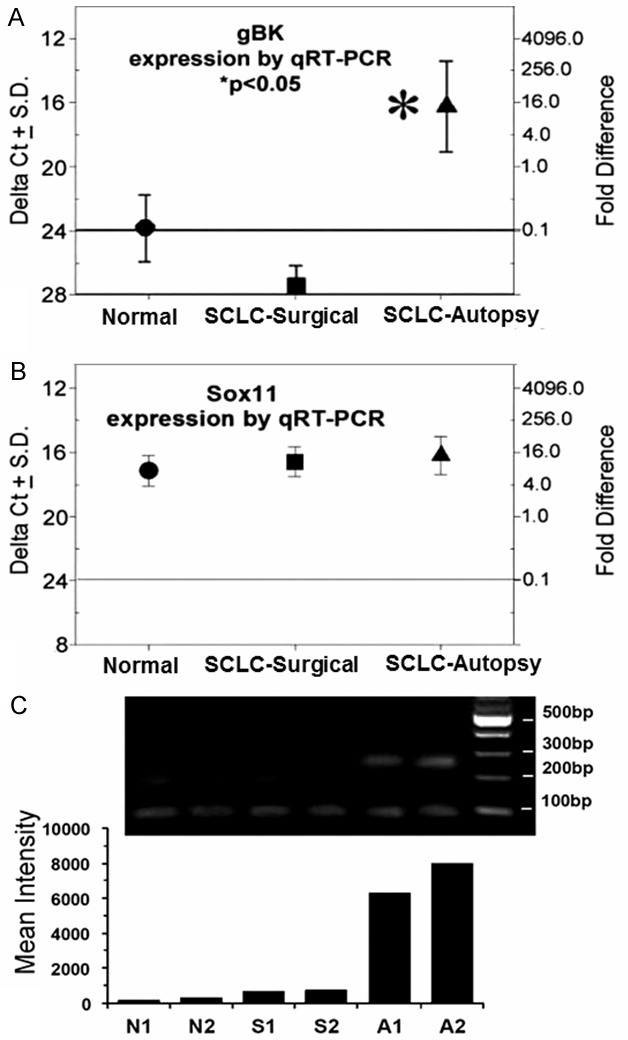

Clinical small cell lung cancers possess more gBK mRNA taken at autopsy than from initial surgical resected specimens

Specimens taken from patients at autopsy (n=3) who did not have any cancer in the lung and were used as negative controls. Autopsy-derived SCLC (Stage IV with multiple metastases) expressed elevated levels of gBK mRNA compared by using qRT-PCR (Figure 5A). We estimated the degree of gBK expression was about 160-fold higher than that in normal lung tissue. The detection of gBK mRNA from the nine primary SCLC samples (Stages IA, IB, IIIA IIIB, all localized tumors to primary nodular or draining lymph nodes) taken from surgical resections at initial diagnosis was also low. These lower transcription levels are assumed to be at the limitation of detection with this technology and not significantly different from that displayed by the non-cancerous lung tissue. By a Student’s t test, the mRNA levels derived from the SCLC autopsy tissue was significantly elevated (P<0.05) compared to the two other sets of samples, non-cancerous lung or early-stage surgical SCLC specimens. Samplings taken from other parts of the same extensive tumor at autopsy showed no differences in qRT-PCR results, eliminating the possibility of tumor heterogeneity or sampling error.

Figure 5.

RT-PCR of detection of gBK mRNA in normal tissue and in surgical and autopsy samples show a differential pattern within SCLC specimens. The RNA was extracted from three non-cancer containing lungs derived from autopsies (circles), nine samples derived from surgical resections of SCLC (squares), and three SCLC autopsy specimens (triangles). The amount of gBK mRNA was quantitated by a ΔCt value (left y-axis) compared to the 18S RNA. The ΔCt value of 20 was given an arbitrary value of 1 and the fold-difference is presented on the corresponding point on the right y-axis. The horizontal line represents the cut-off value (0.1-fold) that we believe represents a biologically significant value (23). (Panel A) Shows the data using gBK-specific primers, while (Panel B)Shows the data using Sox11 qRT-PCR specific primers. Asterisk indicates a P<0.05. (Panel C) Displays the amplicons isolated from non-cancerous lung (N1 + N2), surgical resected SCLC (S1 + S2) and SCLC autopsy samples (A1 + A2) after being amplified 35 times and run on a 2% agarose gel. The right lane shows the molecular weight markers. The smallest bands (67 base pairs) represent the native BK channel, the middle sized bands are the hbr5 isoform (157 base pairs) and the largest band (253 base pairs) is the gBK. The bottom histogram represents the densitometric readings of the 253 base pair bands.

We used Sox 11, a transcription factor found in lung cells [28,29], as a specificity control. The expression of Sox11 mRNA was indistinguishable among the three lung tissues subsets (Figure 5B). We also saw an identical expression patterns with Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein L (HNRPL), which had ΔCt scores between 16 and 18 (data not shown). These findings eliminate the possibility that RNA degradation or other non-specific artifacts were complicating the analysis of gBK expression within the SCLC autopsy samples.

We designed primers to detect the 5’ and 3’ flanking regions of the BK native channel so that we could also detect the hbr5 (the hbr5 isoform contains an additional 29 amino acids inserted into the basic BK channel; hbr5 is always associated with gBK, but hbr5 can be expressed without the gBK insert) and gBK inserts, and confirm the expression of these splice variants using differential gel electrophoresis. Figure 5C shows the gel electrophoretic pattern of samples of the PCR amplification of non-cancerous lung, SCLC surgical and autopsy specimens. The samples derived from the noncancerous and surgical SCLC displayed little, if any gBK could be found at the predicted 260 base pairs, while these specimens showed weak bands of the native BK and hbr5 amplicons. In contrast, only the SCLC autopsy material displayed the amplified gBK sequences. The densitometric readings of the gBK specific bands are shown as a histogram under the gel and confirm the visual observations. Thus, genetic studies confirm the presence of the gBK mRNA within the SCLC.

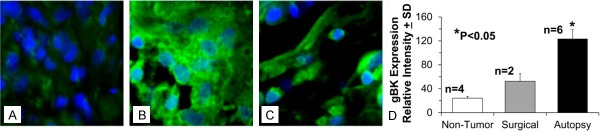

gBK protein expression is detected very highly in late stage SCLC

We next examined archival SCLC tissues to confirm whether the gBK protein was present within SCLC at the time of the autopsy. We found two cases of surgical SCLC from patients at their initial diagnosis (Stage IB and Stage IIIA) and six autopsy cases with late stage IV disease each with multiple (>5) metastatic lesions. Immunostained sections of the specimens with the gBK-specific channel antibody (Figure 6) show representative surgical SCLC (Stage IB; Figure 6A) and autopsy (Stage IV; Figure 6B and 6C) cases. The surgical sample taken at the time of initial diagnosis (Stage IB) had minimal gBK expression. The other surgical SCLC (Stage IIIA) also was negative (negative data not shown). The autopsy derived SCLC cells possessed the higher amount of gBK protein. We noted that when the SCLC cells taken from autopsy are densely packed, the gBK staining pattern is uniform (Figure 6B), but at the periphery of the tumor, where there is a more loose association of the tumor cells, there appears to be some polarity of gBK expression within the SCLC cells (Figure 6C). The composite summary showing the average fluorescence of 4 non-cancer lung tissues, 2 SCLC surgical and 6 additional autopsies from SCLC patients are displayed in Figure 6D. There is a statistical significant difference (P<0.05) between the gBK fluorescent intensity obtained from the SCLC autopsy tissue when compared to the non-cancerous lung or surgical SCLC tissue.

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescence demonstrates that only SCLC autopsy samples display gBK protein by immunofluorescence. Histology blocks were from a patient with the SCLC taken at the initial analysis of SCLC (Panel A) Stage 1B; two other SCLC samples were obtained from two other the autopsy of patients at with (Stage IV) of the time of their autopsies are examined. The blocks were cut and then stained with the anti-gBK antibody (green) and counterstained with a nuclear dye (blue). Only autopsy SCLC samples (shown in Panels B and C) were deemed to be strongly gBK-positive. (Panel B) Shows SCLC when the cancer cells are densely packed, while (Panel C) shows the SCLC at the periphery of the tumor. Magnification is 100X. The data showing the isotypic control staining is not shown, since it was negative and is not shown for the sake of brevity. Additional paraffin blocks were cut from different patients, stained, and analyzed for gBK expression. (Panel D) Shows the quantitative fluorescent pixel intensity analysis of gBK staining in non-tumor lung tissue (4 samples), SCLC surgical (2 samples), and SCLC autopsy (6 different patients). Only autopsy samples were determined to be strongly gBK positive. Statistical significance (P<0.05) by a Student’s t test is denoted by the asterisk.

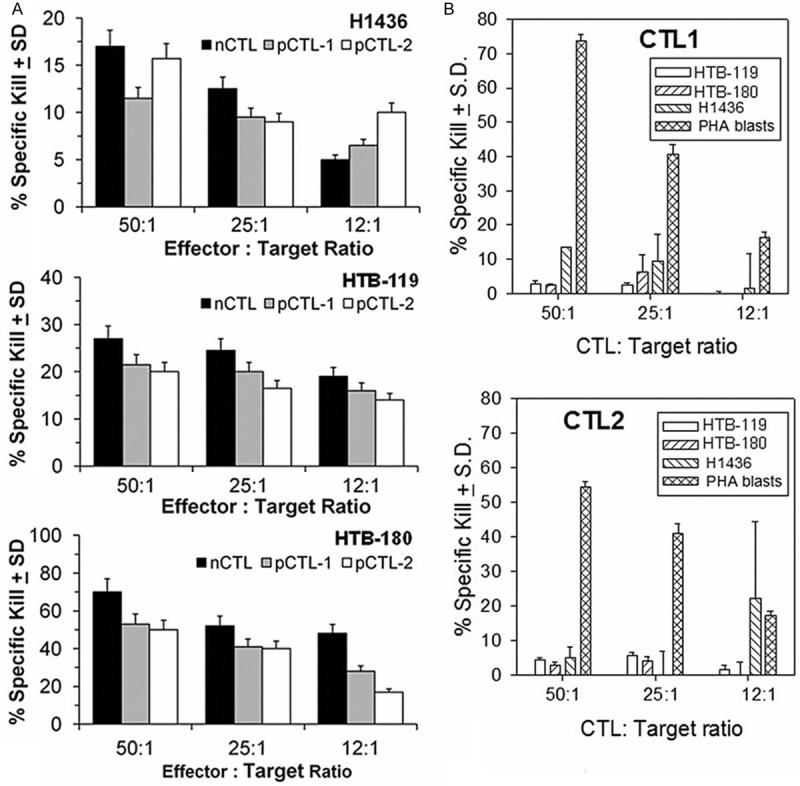

Human gBK-specific CTL will kill HLA-A2+ cells expressing the gBK peptides

In prior work [10] with the human U251 glioma model, we showed there are two peptides derived from the gBK: SLWRLESKG (gBK704-712 or gBK1 peptide) and GQQTFSVKV (gBK722-730 or gBK2 peptide), both peptides could elicit CTL responses that were HLA-A*0201 restricted and killed those glioma cells. The CTL also showed killing of the SCLC cells, which are HLA-A2+ and gBK+. Two of the donors of the CTL came from glioma patients who had gBK+ gliomas and were HLA-A*0201 positive [10]. These gBK1- and gBK2- specific CTL lysed HLA-A2+ SCLC tumor cells that also express gBK (HTB-119, HTB-180, H1436) in 6 hr Cr51 release assays (Figure 7A); the killing displayed against H1436 was the weakest. Nevertheless, the CTL killed the HLA-A2+ SCLC that possessed gBK.

Figure 7.

Only gBK-specific CTLs kill SCLC cell lines. CTL generated from a normal donor and 2 patients with a gBK+ tumors can kill SCLC cell lines. Panel A: Shows the CTLs specifically lyse the three different Cr51-labeled SCLC target cell lines (H1436, HTB-119 and HTB-180) at multiple effector to target cell ratios. The CTL were derived from one HLA-A2+ normal donor (nCTL) and two HLA-A2+ GBM patients (pCTL1 + pCTL2), whose tumors were gBK-positive. The gBK-specific CTL were stimulated by gBK peptides and were used to kill the 3 SLCL cell lines (H1436, HTB-119 and HTB-180) that were pre-labeled with Cr51. Panel B: Illustrates that the SCLC cell lines are not susceptible to alloresponsive CTLs. Alloreactive CTL from two different normal donors were sensitized towards the class 1 antigens of the HLA-A*30+ donor supplying the stimulator cells. They were tested against the same three SCLC cell lines or against the positive control PHA-stimulated lymphoblasts in 6 hr cytolytic assays.

As a further specificity control, we showed that not all CTL will spontaneously lyse the SCLC cells. We used alloresponsive CTL directed towards the HLA-A*30, HLA-B*72/B*61 and HLA-C*2/C*10 haplotype. Two different CTL preparations were generated and allowed to interact with the SCLC target cells along with lymphoblasts (PHA stimulated) displaying the HLA antigens to which the CTL were sensitized. Figure 7B shows that both of these allogeneic CTL populations fail to kill the HLA-A2+ SCLC cells, but specifically killed the HLA-A30+ PHA blasts with the alloantigens to which they were sensitized. Thus, the three SCLC cell lines were not naturally susceptible to killing by every CTL.

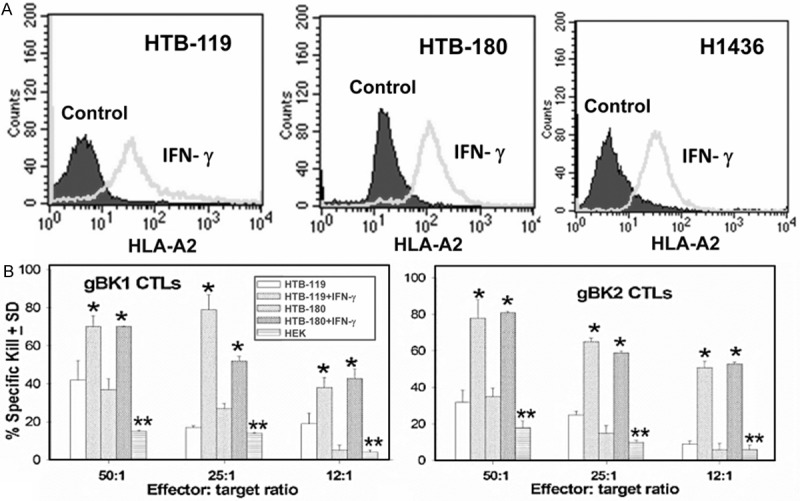

Human IFN-γ enhances the CTL-mediated killing of the HTB-119 and HTB-180 SCLC cells

Human SCLC are reported as expressing low amounts of MHC on their surfaces; the amount of MHC class I on the surfaces of SCLC can be up-regulated upon exposure to IFN-γ [30,31]. CTL and NK cells do mediate other biological responses besides cytotoxicity, such as release of cytokines, such as IFN-γ and TNF-α, which can have differential effects. Upon culture of the SCLC cells with IFN-γ, MHC class I was enhanced (Figure 8A), as expected. We used anti-gBK specific CTL to kill the target cells HTB-119 and HTB-180 SCLC, which were stimulated for one day with or without IFN-γ. The CTLs showed enhanced-cytotoxicity against the SCLC cell lines that were stimulated overnight with IFN-γ, compared to their untreated counterparts (Figure 8B) (P<0.05). We also tested HEK cells, which are HLA-A2+, but are gBK-negative, as negative control targets. None of the CTL killed the HEK cells, as would be predicted.

Figure 8.

IFN-γ augments HLA-A2 expression on SCLC cell lines and induces better gBK-specific CTL-mediated cytolysis of the SCLC cells. SCLC cells were either incubated with or without (control) IFN-γ overnight. Aliquots of the cells were stained for cell surface HLA-A2 by using the monoclonal anti-HLA-A2 antibody (Panel A). Ten thousand cells were analyzed. By Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics, significant differences (P<0.05) were seen with in gBK expression within all three SCLC cell lines. (Panel B) Afterwards, aliquots of those IFN-γ treated cells were used as target cells by the CTLs were incubated at various effector to target cell ratios with CTL directed towards the gBK1 (Left Panel B, left) or gBK2 (Right Panel). HEK cells which are HLA-A0201+ but gBK negative were used as negative controls. The cytotoxicity assay was assessed at 6 hrs. The asterisks indicate significant differences (P<0.05) in lysis were obtained between the SCLC untreated and the respective SCLC cell line treated with IFN-γ. The double asterisk represents the significant values of the killing of between SCLC cells with the HEK cells (P<0.05).

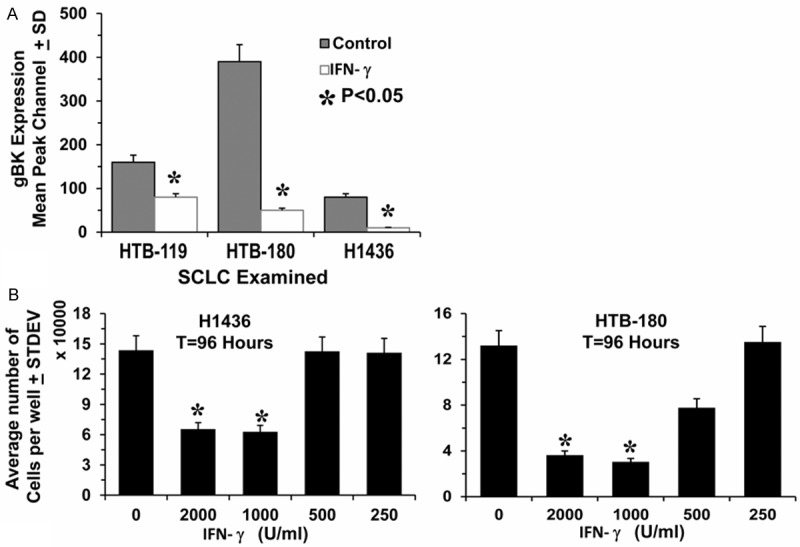

Human IFN-γ diminishes gBK expression and inhibits the proliferation of SCLC cells

There was an unexpected inhibition of gBK expression after 1 day of treatment with recombinant IFN-γ (Figure 9A). This observation was successfully confirmed twice.

Figure 9.

IFN-γ inhibits gBK expression and inhibits SCLC cell proliferation. (Panel A) Shows aliquots of IFN-γ treated SCLC cells that were used from Figure 7 (Panel A). These cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained for gBK expression (Panel A). The data is presented for the sake of simplicity as only the average of gBK staining, expression minus isotypic control staining is displayed (n=3). (Panel B) Demonstrated that 1,000 U/ml and 2,000 U/ml of recombinant IFN-γ inhibits SCLC cell proliferation in vitro. Ten thousand H1436 and HTB-180 cells were plated within 96 well plates along with graded doses of recombinant IFN-γ for 96 hrs. One hour prior to termination, 20 μl of PrestoBlue was added to the cultures and incubated at 37°C. The plates were read and calculated for the number of viable cells present. Asterisks demonstrate significance (P<0.05) differences from the control values.

The down-regulation of gBK induced by IFN-γ suggested that this cytokine could inhibit the growth of SCLC. It was previously reported that interfering with BK channel function can inhibit cancer cell proliferation and cell migration [32-37]. To determine the effect of IFN-γ on cell proliferation, we incubated the H1436 and HTB-180 cells with varying doses of IFN-γ for 96 hours (Figure 9B). For both cell lines, doses of 1,000 and 2,000 units/ml IFN-γ significantly (P<0.05) inhibited the growth of the cells. HTB-180 cells were slightly more sensitive to the IFN-γ because the concentration of 500 units per ml proved to be somewhat more cytostatic, by inhibiting the growth of the cells by 40%.

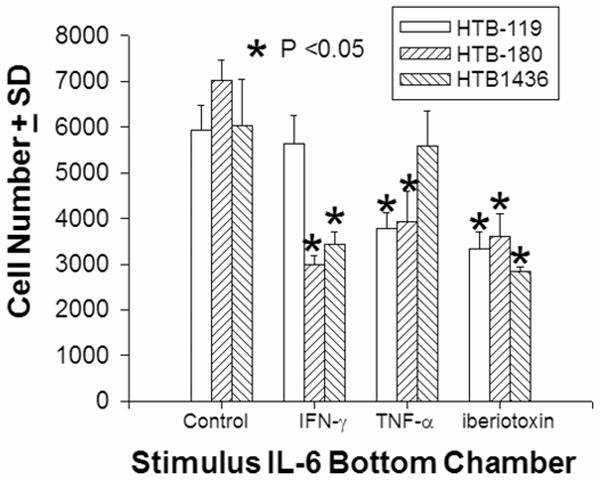

Recombinant IFN-γ, TNF-α and iberiotoxin prevent SCLC transmigration

Th1 T cells and CTL release IFN-γ and TNF-α. We tested the possibility whether these cytokines or direct inhibition of BK channels with iberiotoxin could prevent SCLC from migrating through 5 μm pores in response to interleukin-6. Overnight incubation with IFN-γ, TNF-α or iberiotoxin, prevented the 3 SCLC cells from penetrating through 5 μm pores (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

IFN-γ, TNF-α, and Iberotoxin prevent SCLC transmigration. Fluorescent-labeled SCLC cells were placed in the top chamber of a transwell plate with either 10 ng/ml rhIFN-γ or rhTNF-α or 0.05 μM iberiotoxin; 100 ng/ml of rhIL-6 was placed in the bottom chamber of the (NeuroProbe, 5 μm pore size chemotaxis system), then incubated at 37°C for 5 hours. Cells that passed through the pores into the bottom chamber were collected. The average cell number ± standard deviation is presented. Asterisks denote significance (P<0.05) differences from the control values.

Discussion

Ions (potassium, sodium, calcium, chloride) are ubiquitously found on almost every cell in the body. Ion channels which regulate these ions play multiple roles in nerve conductance, muscle contraction, secretion, cell division, and motility. Ion channels are speculated to play an important role in glioma biology, including such functions as cell migration and division [32,33]; these channels may have identical roles in other tumor cell types, including SCLC [34-37]. BKα channels have a complex splicing pattern with multiple known isoforms [38]. Isoform 7 was genetically cloned by Liu and coworkers in 2002 and was called the glioma BK channel, gBK [9]; this splicing variant containing an extra inserted 33 amino acid sequence was associated with cancer cells displaying a more aggressive phenotype. gBK has three possible intracellular phosphorylation sites, which may have interactions with casein kinase IIα, protein kinase C, and calmodulin kinase protein kinase II that may produce a more malignant behavior than those that only utilize BK channels.

SCLC originate from neuro-endocrine precursor cells [15,16], and SCLC are considered invasive cancers [16,17]. Both SCLC and gliomas have similar mechanisms of motility, although not identical. SCLC is described as having an amoeboid type of migration while gliomas are considered to have a mesenchymal pattern of motility [39]. The possibility does exist that these types of migration can be interchanged with slight genetic alterations [39]. We postulated that ion channels like gBK could be playing a similar type role with SCLC, as they supposedly do with glioma cells. In this respect gBK may act more like a tumor facilitator, which helps the tumor cells spread, as opposed to being considered a classic oncogene, which transforms cells into a more malignant phenotype.

In the present study, we showed that gBK is expressed within 3 human SCLC cell lines (HTB-119, HTB-180 and H1436) (Figure 1). These ion channels proved to be functional, in that whole-cell K+ currents confirmed conductance patterns consistent with BK channels. The compound, paxilline, inhibited the whole-cell K+ currents produced by gBK channels in dose-dependent kinetics (Figure 2A and 2C). The BK specific activator, pimaric acid, released a K+ dependent current (Figure 2D). The gBK insert resides within the C-terminal region away from the key functional domains of the BK channel; i.e., the voltage sensitive region, pore domain and Ca2+ binding pockets in the RCK1 and RCK2 regions. So these functional properties are consistent with other BK channel tracings [22]. Prolonged exposure to pimaric acid induced cell swelling within 20 minutes (Figure 3B); the specific BK channel inhibitor, iberiotoxin, prevented the pimaric acid-induced swelling. The extended exposure to BK channel activators killed the SCLC by five hours (Figure 3C and 3D). Likewise, iberiotoxin also prevented this cell lysis by BK channel activation (Figure 3C and 3D). Upon gBK transduction into HEK cells we conclusively demonstrate that gBK channels are functional by electro-physiological tracings and by cell swelling (Figure 4). From our previous studies with BK channel activation with rat and human gliomas, we noted that using the same dose of pimaric acid or phloretin killed the brain cancers in 12 or 16 hours, respectively [26,27]. Killing of SCLC by prolonged BK activation could be used as a novel whole tumor cell vaccine like we saw with rat glioma cells [26]. The mRNA for gBK is only highly expressed within SCLC autopsy specimens using quantitative real time PCR technology (Figure 5A), suggesting this might be a marker of end stage disease. We further confirmed the qRT-PCR data by doing immunofluorescence analysis with 6 randomly chosen archival paraffinembedded SCLC autopsy cases (Figure 6D). Thus, the gBK protein is indeed present within terminal SCLC specimens.

The presence of gBK in SCLC might therefore be considered a “Death Biosignature.” The transcription factor, Sox11, known to be active in lung development [28,29], failed to show any contrasting expression within the three sampled populations (Figure 5B); this eliminated the possibility of any systemic experimental artifact. Using a differential gel electrophoretic technique with the BK amplicons, we showed that the BK channel mRNA within the terminal SCLC samples have the larger gBK transcripts (Figure 5C) and confirm the qRT-PCR analysis. The specific-gBK antibody showed that this molecule is displayed as a protein (Figure 6B and 6C) in autopsy samples. The flow cytometric analysis revealed that gBK was strongly present on the HTB-119 and HTB-180 cells, while being weakly displayed by the H1436 cells. The initial paper that described the origins of these SCLC cell lines reported that HTB-119 and HTB-180 cells came from patients who received prior chemo and radiation therapy after their respective diagnosis. In contrast, the H1436 cells were isolated from an untreated cancer [40,41]. So the expression of gBK within these cell lines may reflect the evolution of SCLC cancer as it progresses towards its terminal phase. Electron microscopy revealed that SCLC cells have scant amounts of endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi and mitochondria [40-42]. Glioma cells in contrast have more cytoplasmic internal organelles. BK can be found in all those organelles and therefore glioma cells have more intracellular potassium ion stores to deplete before cytotoxicity occurs. The gBK was found on the membrane of the SCLC. The shortened time to kill the SCLC cells by prolonged BK channel activation could reflect that only membrane BK activation is needed. Therefore, SCLC has a somewhat different BK channel biology than that of glioma cells. If one wants to only study membrane BK biology without the effects of the other BK channels coming from other organelles, then SCLC are perhaps the best cells to use.

The gBK inserted region contains protein sequences that can be processed into peptides that bind to the MHC antigens and provoke human immune responses restricted to the HLA-A*0201 allele [10]. Two peptides, SLWRLESKG gBK704-712 (gBK1 peptide) and GQQTFSVKV gBK722-730 (gBK2 peptide) successfully generated human HLA-A0201-restricted CTL. These CTLs strongly killed two HLA-A2+ human SCLC cells (HTB-119 and HTB-180 cells) that co-expressed gBK (Figure 7A). These CTL failed to kill HLA-A2+ HEK cells, which are gBK-negative (Figure 8B). Our work also illustrates that the SCLC cells do sufficiently process gBK peptides so that the T cells can respond to them in the context of HLA-A2. The gBK1 and gBK2 specific CTL also specifically killed human T2 hybridoma cells that were exogenously loaded with their respective gBK peptides; these CTL failed to kill T2 cells loaded with the irrelevant influenza M1 peptide [10].

CTL do have other anti-tumor functions besides cytotoxicity, such as proinflammatory cytokine secretion, including IFN-γ and TNF-α. SCLC have low expression of MHC class I expression [19,20,30,31]. This diminished HLA expression however is not zero (Figure 9), so some initial recognition of the in vivo SCLC by T cells is possible. Upon culturing the SCLC cells with IFN-γ, MHC class I expression was enhanced (Figure 9A) as expected. These IFN-treated SCLC then became better targets for the gBK-specific CTL (Figure 9B). An unexpected finding was that gBK protein was significantly reduced within the SCLC cells, as determined by intracellular flow cytometry (Figure 9A) after 24 hrs. When we performed in vitro quantitative proliferation assays, recombinant IFN-γ significantly inhibited the growth of the SCLC cells. IFN-γ slowed but did not completely inhibit the proliferation of the SCLC cells (Figure 9B). Ion channels are thought to play a role in cell division; hence they may provide a mechanism through which IFN-γ can slow the growth of cancer cells. It has been known for many years that IFN-γ inhibits cancer cell growth through a pathway independent of direct cytotoxicity [43,44]. IFN-γ along with TNF-α induces tumor cell senescence, including the Hop-62 SCLC cell line [45]. CTL may display anti-tumor functions distinct from direct cellmediated killing. Interfering with BK channel transcription inhibited the proliferation of some tumor cells [5,34-37]. Hence, activated T cells may release cytokines upon recognition of gBK peptides in the context of the MHC, thereby providing an additional anti-tumor mechanism used against many tumor types, since almost all tumor cells express gBK [9,10]. We tested this possibility by showing that the BK channel inhibitor, iberiotoxin, directly prevented SCLC from passing through 5 μ pores. Both IFN-γ and TNF-α inhibited SCLC transmigration (Figure 10). IFN-γ does inhibit human A172 glioma cell transmigration [46]; A172 cells do express gBK (Ge, Hoa and Jadus, unpublished results). Similar anti-invasive effects of IFN-γ were noted with B16 melanoma [47] and thyroid cancer cells, too [48].

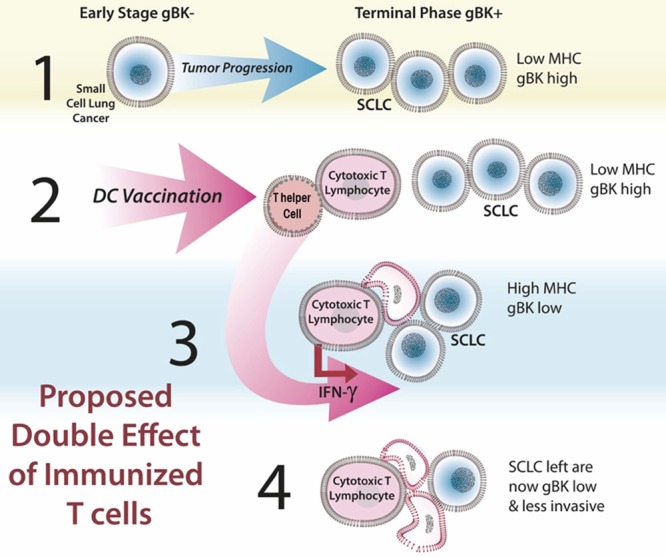

We propose a model by which immunity based on gBK could operate, Figure 11. During the early stages of SCLC, these cancer cells normally express low levels (but not zero amounts) of MHC class I and are largely gBK negative (Step 1). As the tumor progresses, the cancer cells will express more gBK; this “Death Biosignature” may be a prognostic marker indicating the terminal phases of SCLC. Thus, vaccination of SCLC patients with an anti-gBK strategy should be done after the initial chemo and radiation therapies before the appearance of the gBK neoantigen becomes manifest. If the patient could be vaccinated with autologous dendritic cells pulsed with the gBK protein or peptides, endogenous T cells (both CD4 and CD8) could be induced (Step 2) and these immunized lymphocytes could search for SCLC cells that begin to display gBK and attack the SCLC in two ways, according to the previously proposed “immunoprevention” model [49]. The first way could be through the traditional cell-mediated cytotoxicity by CD8+ T cells (Step 3). However, CTLs and CD4 Th1 cells can release IFN-γ, which may be released and stimulate the SCLC to produce more MHC class I and II, so that better recognition of the SCLC occurs in return. By SYFPEITHI analysis, gBK does have several sequences that are predicted to bind to human HLA-DRB1 alleles (*0101, *0301, *0401, *0701 and *1501). The released IFN-γ could suppress the expression of gBK and slow the growth and invasion of the SCLC cells via senescence (Step 4). Even if only the high expressing gBK SCLC cells are prevented from expanding by an immunotherapeutic approach, using either active or passive methods, then the tumor cell population as a whole might be sufficiently reduced, thereby slowing the progression of SCLC to terminal stage while concurrently improving patient survival.

Figure 11.

Proposed model by which a gBK-based immunity can inhibit SCLC growth.

In summary, we find that gBK channels are genetically expressed within human SCLC taken from autopsies but not from early surgical resections. This may indicate that gBK is an antigen prognostic for the end stage of the cancer. A gBK specific antibody confirmed that the gBK protein is found within human clinical SCLC samples and in SCLC cell lines. Exposure to BK channel activators caused the cells to swell within 20 minutes and after five hours the SCLC cancer cells were killed. gBK specific peptides provided sufficient stimulation to produce HLA-A2 restricted human CD8+ CTL that killed gBK+ SCLC cells. Upon stimulation of SCLC with IFN-γ, the amount of HLA-A2 increased, allowing the gBK-specific CTL to better kill the gBK+ SCLC cells. IFN-γ reduced the expression of gBK and recombinant IFN-γ slowed the growth and transmigratory behavior of the SCLC cells in vitro. Thus, immunological targeting of glioma BK associated ion channels may be a novel way to treat the terminal stages of SCLC. Vaccination using gBK may provide a temporary remission for these SCLC patients through two distinct processes; i.e., through a classic CTL-mediated pathway and a cytokine inducing down-regulation of gBK, which may inhibit SCLC function.

Acknowledgements

C.A.K. is funded by NIH grants: R01CA125244 and R01CA154256. M.R.J. is supported by a VA Merit Review. C.B. is funded by Department of Defense grant BC096018.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Gulley L, Drake CG. Immunotherapy for prostate cancer: Recent advances, lessons learned, and areas for further research. Clin Can Res. 2011;17:3884–3891. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prins RM, Soto H, Konkankit V, Odesa SK, Eskin A, Yong WH, Nelson SF, Liau LM. Gene expression profile correlates with T cell infiltration and survival in glioblastoma patients vaccinated with dendritic cell immunotherapy. Clin Can Res. 2011;17:1603–1615. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jadus MR, Natividad J, Mai A, Ouyang Y, Lambrecht N, Szabo S, Ge L, Hoa N, Dacosta-Iyer MG. Lung Cancer: a classic example of tumor escape and progression while providing opportunities for immunological intervention. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:160724. doi: 10.1155/2012/160724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnould L, Gelly M, Penault-Llorca F, Bonnetain F, Migeon C, Cabaret V, Fermeaux V, Bertheau P, Garnier J, Jeannin JF, Coudert B. Trastuzumab- based treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer: an antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity mechanism? Brit J Cancer. 2006;94:259–267. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weaver AK, Liu X, Sontheimer H. Role for calcium-activation channels (BK) in growth control of human malignant glioma cells. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78:224–234. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ransom CB, Xiaojin L, Sontheimer H. BK channels in human glioma cells have enhanced calcium sensitivity. Glia. 2002;38:281–91. doi: 10.1002/glia.10064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ransom CB, Sontheimer H. BK channels in human glioma cells. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:790–801. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.2.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Debska G, Kicinska A, Dobrucki J, Dworakowska B, Nurowska E, Skalska J, Dolowy K, Szewczyk A. Large-conductance K+ channel openers NS1619 and NS004 as inhibitors of mitochondrial function in glioma cells. Biochem Pharm. 2003;65:1827–1834. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X, Chang Y, Reinhart PH, Sontheimer H. Cloning and characterization of glioma BK, a novel BK channel isoform highly expressed in rat glioma cells. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1840–1849. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01840.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ge L, Cornforth AN, Hoa N, Bota DA, Mai A, Kim DI, Chiou SK, Hickey MJ, Kruse CA, Jadus MR. Glioma BK channel expression in human cancers and possible T cell epitopes for their immunotherapy. J Immunol. 2012;189:2625–2634. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sontheimer H. An unexpected role for ion channels in brain tumor metastasis. Exp Biol Med. 2008;233:779–791. doi: 10.3181/0711-MR-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dang AQ, Hoa NT, Ge L, Arismendi Morillo G, Paleo B, Gomez EJ, Shon DJ, Hong E, Aref AM, Jadus MR. Using REMBRANDT to paint in the details of glioma biology: Applications for future immunotherapy. In: Lichtor T, editor. Evolution of the Molecular Biology of Brain Tumors and the Therapeutic Implications. Chapter 6. 2013. pp. 167–200. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao H, Sokabe M. Tuning the mechanosensitivity of a BK channel by changing the linker length. Cell Res. 2008;18:871–878. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinle M, Palme D, Misovic M, Rudner J, Dittman K, Lukowski R, Ruth P, Huber SM. Ionizing radiation induces migration of glioblastoma cells by activating BK K+ channels. Radiother Oncol. 2011;101:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forster BB, Müller NL, Miller RR, Nelems B, Evans KG. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the lung: clinical, radiologic, and pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1989;170:441–445. doi: 10.1148/radiology.170.2.2536187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink K, Harris CC. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. In: Travis WD, Brambilla E, Müller-Hermelink EK, Harris CC, editors. World health organization classification of tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. pp. 9–122. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackman DM, Johnson BE. Small-cell lung cancer. Lancet. 2005;366:1385–1396. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67569-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma S, Zhu L, Yang SC, Zhang L, Lin J, Hillinger S, Gardner B, Reckamp K, Strieter RM, Huang M, Batra RK, Dubinett SM. Cyclooxygenase 2 inhibition promotes IFN-γ-dependent enhancement of antitumor responses. J Immunol. 2005;175:813–819. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aladin F, Lautscham G, Humphries E, Coulson J, Blake N. Targeting tumour cells with defects in the MHC class I antigen processing pathway with CD8+ T cells specific for hydrophobic TAP- and Tapasin-independent peptides: the requirement for directed access into the ER. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:1143–1152. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0263-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen HL, Gabrilovich D, Tampe R, Girgis KR, Nadaf S, Carbone DP. A functionally defective allele of TAP1 results in loss of MHC class I antigen presentation in a human lung cancer. Nature Genet. 1996;13:210–213. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beeton C, Pennington MW, Wulff H, Singh S, Nugent D, Crossley G, Khaytin I, Calabresi PA, Chen CY, Gutman GA, Chandy KG. Targeting effector memory T cells with a selective peptide inhibitor of Kv1.3 channels for therapy of autoimmune diseases. Mol Pharm. 2005;67:1369–1381. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.008193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu X, Laragione T, Sun L, Koshy S, Jones KR, Ismailov II, Yotnda P, Horrigan TF, Pércio S, Gulko S, Beeton C. KCa1.1 potassium channels regulate key proinflammatory and invasive properties of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4014–4022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.312264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang JG, Eguchi J, Kruse CA, Gomez H, Fakhrai H, Schroter S, Ma E, Hoa N, Minev B, Delgado C, Wepsic HT, Okada H, Jadus MR. Antigenic profiling of glioma cells to generate antigenic vaccines or dendritic cell-based therapeutics. Clin Can Res. 2007;13:566–575. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ge L, Cornforth AN, Hoa NT, Delgado C, Zhou YH, Jadus MR. Differential glioma-associated tumor antigen expression profiles of human glioma cells grown in hypoxia. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042661. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang CL, Liu YY, Ma YG, Xue YX, Ren Y, Liu XB, Li Y, Li Z. Curcumin blocks small cell lung cancer cells migration, invasion, angiogenesis, cell cycle and neoplasia through janus kinase-STAT3 signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037960. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoa N, Zhang G, Delgado C, Myers MP, Callahan LL, Vandeusen G, Wepsic HT, Jadus MR. BK channel activation results in paraptosis: a possible mechanism to explain monocyte-mediated killing of tumor cells expressing membrane macrophage colony stimulating factor. Lab Invest. 2007;87:115–129. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoa NT, Myers MP, Zhang JG, Delgado C, Driggers L, Callahan LL, Vandeusen G, Schiltz PM, Wepsic HT, Douglass TG, Pham T, Bhakta N, Ge L, Jadus MR. Molecular mechanisms of paraptosis induction: implications for a non-genetic modified tumor vaccine. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004631. doi 10.1371/journal. pone0004631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jay PC, Gozé C, Marsollier C, Taviaux S, Hardelin JP, Koopman P, Berta P. The human SOX11 gene: cloning, chromosomal assignment and tissue expression. Genomics. 2005;29:541–545. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.9970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sock E, Rettig SD, Enderich J, Bosl MR, Tamm ER, Wegner M. Gene targeting reveals a widespread role for the high-mobility group transcription factor Sox11 in tissue remodeling. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6635–6644. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6635-6644.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Traversari C, Meazza R, Coppolecchia M, Basso S, Verrecchia A, van der Bruggen P, Ardizzoni A, Gaggero A, Ferrini S. IFN-γ gene transfer restores HLA-class I expression and MAGE-3 antigen presentation to CTL in HLA-deficient small cell lung cancer. Gene Ther. 1997;4:1029–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marley GM, Doyle LA, Ordóñez JV, Sisk A, Hussain A, Chiu RW. Potentiation of interferon induction of class I major histocompatibility complex antigen expression by human tumor necrosis factor in small cell lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6232–6236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bordey A, Sontheimer H, Trouslard J. Muscarinic activation of BK channels induces membrane oscillations in glioma cells and leads to inhibition of cell migration. J Membrane Biol. 2000;176:31–40. doi: 10.1007/s00232001073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraft R, Krause P, Jung S, Basrai D, Liebmann L, Bolz J, Patt S. BK channel openers inhibit migration of human glioma cells. Pflügers Archiv Eur J Physiol. 2003;446:248–255. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spitzner M, Ousingsawat J, Scheidt K, Kunzelmann K, Schreiber R. Voltage-gated K+ channels support proliferation of colonic carcinoma cells. FASEB J. 2007;21:35–44. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6200com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han X, Wang F, Yao W, Xing H, Weng D, Song X, Chen G, Xi L, Zhu T, Zhou J, Xu G, Wang S, Meng L, Iadecola C, Wang G, Ma D. Heat shock proteins and p53 play a critical role in K+ channel-mediated tumor cell proliferation and apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2007;12:1837–46. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pancrazio JJ, Tabbara IA, Kim YI. Voltage-activated K+ conductance and cell proliferation in small-cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 1993;13:1231–1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han X, Xi L, Wang H, Huang X, Ma X, Han Z, Wu P, Ma X, Lu Y, Wang G, Zhou J, Ma D. The potassium ion channel opener NS1619 inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in A2780 ovarian cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;375:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shipston MJ. Alternative splicing of potassium channels: a dynamic switch of cellular excitability. Trends Cell Biology. 2001;11:353–358. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedl P, Wolf K. Tumour-cell invasion and migration: diversity and escape mechanisms. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2003;3:362–374. doi: 10.1038/nrc1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bepler G, Jaques G, Neumann K, Aumüller G, Gropp C, Havemann K. Establishment, growth properties, and morphological characteristics of permanent human small cell lung cancer cell lines. J. Clin. Oncol. 1987;113:31–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00389964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carney DN, Gazdar AF, Bepler G, Guccion JG, Marangos PG, Moody TW, Zweig MH, Minna JD. Establishment and identification of small cell lung cancer cell lines having classic and variant features. Cancer Res. 1985;45:2913–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsumoto T, Terasaki T, Mukai K, Wada M, Okamoto A, Yokota J, Yamaguchi K, Kato K, Nagatsu T, Shimosato Y. Relation between nucleolar size and growth characteristics in small cell lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Sci. 1991;82:820–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1991.tb02708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Denz H, Lechleitner M, Marth C, Daxenbichler G, Gastl G, Braunsteiner H. Effect of human recombinant Alpha-2-and Gamma-interferon on the growth of human cell lines from solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. J Interfer Res. 1985;5:147–157. doi: 10.1089/jir.1985.5.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ücer Y, Bartsch H, Scheurich P, Pfizenmaier K. Biological effects of γ-interferon on human tumor cells: Quantity and affinity of cell membrane receptors for γ-IFN in relation to growth inhibition and induction of HLA-DR expression. Intl J Cancer. 1985;36:103–108. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910360116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Braumüller H, Wieder T, Brenner E, Aßmann S, Hahn M, Alkhaled M, Schilbach K, Essmann F, Kneilling M, Griessinger C, Ranta F, Ullrich S, Mocikat R, Braungart K, Mehra T, Fehrenbacher B, Berdel J, Niessner H, Meier F, van den Broek M, Häring HU, Handgretinger R, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Fend F, Pesic M, Bauer J, Zender L, Schaller M, Schulze-Osthoff K, Röcken M. T-Helper-1 cell cytokines drive cancer into senescence. Nature. 2013;494:361–365. doi: 10.1038/nature11824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knüpfer MM, Knüpfer H, Jendrossek V, Van Gool S, Wolff JE, Keller E. Interferon-γ inhibits growth and migration of A172 human glioblastoma cells. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:3989–3994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma YM, Sun T, Liu YX, Zhao N, Gu Q, Zhang DF, Qie S, Ni CS, Liu Y, Sun BC. A pilot study on acute inflammation and cancer: a new balance between IFN-γ and TGF-β in melanoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:23. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yip I, Pang XP, Berg L, Hershman JM. Antitumor actions of interferon-γ and interleukin-1β on human papillary thyroid carcinoma cell lines. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:1664–1669. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.5.7745015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Forni G, Lollini PL, Musiani P, Colombo MP. Immunoprevention of cancer: is the time ripe? Cancer Res. 2000;60:2571–2575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]