Abstract

Purpose

We assess the association of men's exposure to violence in childhood--witnessing physical violence against one’s mother and being hit or beaten by a parent or adult relative--with their attitudes about intimate partner violence (IPV) against women. We explore whether men’s perpetration of IPV mediates this relationship and whether men’s attitudes about IPV mediate any relationship of exposure to violence in childhood with perpetration of IPV.

Methods

522 married men 18–51 years in Vietnam were interviewed. Multivariate regressions for ordinal and binary responses were estimated to assess these relationships.

Results

Compared to men experiencing neither form of violence in childhood, men experiencing either or both had higher adjusted odds of reporting more reasons to hit a wife (aORs, 95%CIs: 1.43, 1.03–2.00 and 1.66, 1.05–2.64, respectively). Men’s lifetime perpetration of IPV accounted fully for these associations. Compared to men experiencing neither form of violence in childhood, men experiencing either or both had higher adjusted odds of ever perpetrating IPV (aORs, 95%CIs: 3.28, 2.15–4.99 and 4.56, 2.90–7.17, respectively). Attitudes about IPV modestly attenuated these associations.

Conclusion

Addressing violence in childhood is needed to change men’s risk of perpetrating IPV and greater subsequent justification of it.

Keywords: Men's health, Family violence, Vietnam

BACKGROUND

Intimate Partner Violence against Women: Prevalence and Justification

Intimate partner violence (IPV) refers to aggressive or coercive behaviors among dating, cohabiting, or marital partners [1]. Globally, 15%–71% of women report lifetime exposure to physical or sexual IPV [2], and adverse health consequences are common [2–4]. Global advocacy and legislation have ensued to mitigate IPV [5–7].

Attitudes about IPV are one point of intervention, as justifying IPV against women is associated with perpetration and victimization [8]. Beyond the demographic correlates [9–11], exposure to violence in childhood, including witnessing IPV and being hit or beaten, may influence attitudes about IPV into adulthood [12–14]. In poorer settings, the effects of men’s exposure to violence in childhood on their attitudes about IPV, and the reciprocal influences of attitudes and perpetration, are understudied [15]. We assess whether men’s experiences in childhood of witnessing physical IPV against their mother (witnessing IPV) and/or of being hit or beaten by a parent or adult relative (experiencing physical maltreatment) are associated with justifying IPV against women in Vietnam. We, then, explore whether violence in childhood operates, (1) by increasing the risk of perpetrating IPV, which reinforces its justification, and/or (2) by increasing the tendency to justify IPV, which then elevates the risk of perpetration.

Violence in Childhood

Prevalence and Health Consequences

Children may experience many forms of violence [16]. They may witness violence between their parents or other adults and become involved by intervening on the victim’s behalf. Worldwide, approximately 133–175 million children witness IPV annually [17]. Such children often are exposed to direct physical or sexual maltreatment in the family [16]. Some of this exposure may result from children being harmed during an incident of IPV. More often, children are the object of corporal punishment, a form of physical maltreatment.

Influences on Attitudes about IPV and IPV Perpetration

Exposure to IPV and maltreatment in childhood may influence formative perceptions of “normal” intimate relationships. According to social learning theory [18], children who witness inter-parental violence or are maltreated come to see such violence as normal [19 20]. Early normalization of IPV against women may then increase the risk of perpetration [21–23]. In turn, perpetrating IPV may reinforce its justification [24]. Thus, justifying and perpetrating IPV may be mutually causal, especially among those exposed to violence in childhood.

In India, men who witnessed father-to-mother or reciprocal physical violence in childhood were more likely to perpetrate IPV [19]. In meta-analyses, experiencing corporal punishment in childhood has been associated with adult aggression and spousal abuse [25]. Among Chinese immigrant men in the U.S., attitudes about IPV have mediated the relationship of physical violence in childhood and prior-year perpetration of IPV [26]. Among women in Nigeria, tolerance for IPV has mediated the relationship of witnessing violence in childhood and experiencing IPV [27]. Yet, the latter two studies were cross-sectional, precluding directional inferences. A panel study in South Africa showed positive bidirectional associations over time between boys’ attitudes about and perpetration of IPV [24].

Violence in Childhood in East Asia and Vietnam

In East Asia and the Pacific, the lifetime prevalence of moderate physical maltreatment of children is high (39.5%–66.3%) [28]. In Vietnam, almost one third of women (31.5%) have ever experienced physical IPV, of whom more than half have stated that their children witnessed it [29]. “Corporal discipline” in childhood is used strategically to instruct boys about gendered family hierarchies [30]. About 23.7% of mothers have reported that their children experienced physical maltreatment at least once by their husband [29].

In East Asia and the Pacific, various forms of child maltreatment have been associated with poorer mental and physical health, and higher odds of engaging in risky behavior [22]. In a systematic review of studies with women and men, witnessing inter-parental violence has been associated positively with experiencing IPV and suicide ideation [22]. In Northern Vietnam, women who witnessed father-to-mother physical violence were more likely to justify IPV [31]. Exposure to physical maltreatment in childhood may encourage greater acceptance of IPV [13 26]. In Vietnam, the influence of men’s exposure to various forms of violence in childhood on their attitudes about and perpetration of IPV against women is understudied.

Hypotheses

Here, we test whether men’s experiences of witnessing IPV and physical maltreatment in childhood are positively associated with justifying IPV against women in Vietnam. We then explore whether (1) men’s ever perpetration of IPV mediates this relationship, and (2) men’s attitudes about IPV against women mediate any relationship of their exposure to violence in childhood with their IPV perpetration.

METHODS

Sample

This cross-sectional survey was conducted in My Hao district, Hung Yen province, Vietnam (population 97,733) [32]. Married men and women 18–51 years in 74 villages across 12 communes and one district city were eligible for participation. Using a cluster-sampling design, villages were paired by the size of the married population, and 20 pairs of villages were selected with probability proportional to the total married population in the pair relative to the total married population in all 74 villages. Thus, village pairs with a higher proportion of the total married population in all villages were more likely to be selected. For privacy, villages within selected pairs were assigned randomly to the men’s and women’s samples. In each village, 27 households with at least one eligible respondent were selected randomly, and one eligible individual was selected randomly per household. Of 532 men selected, 98.1% (n=522) were interviewed. Other surveys of men in Vietnam have similar response rates [33].

Ten attitudinal questions on physical IPV against women asked "[i]n your opinion, does a man have a good reason to hit his wife” if she: (1) “does not complete her household work to his satisfaction,” (2) “disobeys him,” (3) “refuses to have sexual relations with him,” (4) “asks him whether he has other girlfriends,” (6) “goes out without telling him,” (7) “burns the food,” (8) “neglects the children,” (9) “rudely argues with him,” and (10) “argues with her parents-in-law,” as well as (5) “he finds out that she has been unfaithful.” Possible responses were "yes," "no," and "don't know." Questions on perpetration of physical IPV asked whether men had ever committed the following acts against their current wife: (1) “slapped her or thrown something at her that could hurt,” (2) “pushed her, shoved her, or pulled her hair,” (3) “hit her with your fist or something that could hurt her,” (4) “kicked her, dragged her, or beat her up,” (5) “choked or burned her on purpose,” and (6) “threatened to use or used a gun, knife, or other weapon against her." Possible responses were "yes" or "no." Questions on childhood exposure to violence asked "when you were a child,” “did you ever see or hear your mother being hit by your father (or her husband or boyfriend)" and "…were you ever hit or beaten by your mother, father, or another adult relative?" Possible responses were "yes," "no," and "don't know."

Ethical Considerations

The Institutional Review Boards of Emory University and the Center for Creative Initiatives in Health and Population in Hanoi, Vietnam, approved the study. The Vietnam Union of Science and Technology Associations (VUSTA) and My Hao District Health Center granted permission to conduct the study in Vietnam and in My Hao. Verbal informed consent was confirmed before starting the survey. Interviewers were advanced students at the Hanoi School of Public Health with prior survey experience and two days of training on the questionnaire for this study. Interviewers were gender-matched with participants to enhance disclosure. The survey was administered in private rooms at the commune health station to maintain privacy. Respondents were reimbursed for their travel expenses.

Variables

Outcomes

For attitudes about IPV against women, we created a 0–6 summative scale from 6 of the 10 attitudinal items (3,4,5,6,8,9) that we confirmed using factor analysis to be reliable indicators of a unidimensional construct [34]. The 0–6 and 0–10 scales were highly correlated (Pearson’s r=0.96). Inferences using the two scales were similar, but associations for variables of interest were slightly attenuated with the 0–10- scale (available on request). For this analysis, we trichotomized the 0–6 scale to differentiate men who (1) found no good reason ("no" to all 6 items), (2) some good reasons ("yes" to 1–2 items), or (3) many good reasons ("yes" to 3–6 items) to hit a wife. For lifetime perpetration of physical IPV, we captured whether (=1) or not (=0) the man reported ever committing any of the above six acts against his wife.

Exposure

From questions about witnessing IPV and physical maltreatment in childhood, we created one variable capturing exposure to (1) neither, (2) either but not both, and (3) both. Ninety percent of the 273 men who witnessed IPV or were physically maltreated in childhood experienced the latter alone. Eight men who experienced violence and responded "don't know" to witnessing violence were coded "either, not both." Three men who did not witness violence and responded "don't know" to experiencing violence were coded "neither."

Confounders / Control Mediators

Confounders

The respondents' age in years captured unmeasured period and life-course exposures. Childhood residence before age 12 (grew up in another town versus lived in same commune as a child) captured other childhood experiences. Three men who did not know or specify their childhood residence were coded as living in the same commune as a child.

Control Mediators

Adult socioeconomic mediators included the respondent’s age relative to his wife (same [reference], older, younger), living arrangement (living with neither in-laws nor natal family [reference], living with either/both), number of children ever fathered, completed grades of schooling, schooling relative to wife (same [reference], more, less), income relative to wife (same [reference], more, less), and household wealth index. For respondents with missing data on own (n=2) or wife’s (n=15) schooling, we imputed the average number of completed grades in the observed sample (9.58 and 9.62, respectively). The household wealth index was the score, categorized into tertiles, derived from a principle components analysis of 14 assets and amenities (e.g., computer, flushing toilet; full list available on request).

Analysis

Rao-Scott chi-square tests and t-tests were used to estimate the relationships of childhood exposure to violence with covariates. Using ordinal logistic regression, we estimated three models for the association of childhood exposure to violence with the attitudinal outcome: (1) unadjusted, (2) adjusted for confounders and control mediators, and (3) adding perpetration of IPV as a potential mediator. In Model 3, the proportional odds assumption was met and there was no evidence of multicollinearity [35]. Estimates are interpreted as the (log) odds of finding more versus fewer good reasons for a husband to hit his wife (3–6 versus 1–2 versus 0) per unit change in the explanatory variable. We used logistic regression to estimate three models for the association of men’s exposure to violence in childhood with their lifetime perpetration of physical IPV: (1) unadjusted, (2) adjusted for confounders and control mediators, and (3) adding attitudes about IPV as a potential mediator. Analyses were conducted using SAS-callable SUDAAN 11.0 (RTI, Research Triangle, NC) to account for the complex survey design.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Almost one fourth of the men neither witnessed IPV nor were physically maltreated in childhood (Table 1). Over half experienced one but not both, and almost one fourth experienced both. On most attributes, men exposed to one or neither form of violence in childhood were similar (Table 1); yet, men exposed to one form were younger, on average, and more often were older than their wife, and living in the wealthiest households. Compared to their counterparts, men exposed to both forms of violence in childhood were younger and had fewer children, on average. They also more often were living in the wealthiest and joint households, had more schooling, and compared to their wives, had more schooling, earned more, and were older.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics, Overall and by Type of Exposure to Violence in Childhood, N=522 Married Men 18–51 Years, My Hao district, Vietnam

| By exposure to violence in childhood: |

P-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N=522) |

Botha (N=122) |

Oneb (N=273) |

Neitherc (N=127) |

both vs. neither |

one vs. neither |

both vs. one |

|

| Percent of population (%) | 24.4 | 50.9 | 24.7 | ||||

| Covariates/Control Mediators | |||||||

| Childhood residence (%) | |||||||

| Same residence | 95.9 | 95.6 | 95.5 | 96.9 | 0.517 | 0.287 | 0.961 |

| Other residence | 4.1 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 3.1 | |||

| Age, years | 35.9 | 31.7 | 36.8 | 38.4 | <0.001 | 0.016 | <0.001 |

| Living situation (%) | 0.001 | 0.124 | 0.014 | ||||

| In-laws, natal family, or both | 37.0 | 47.5 | 35.6 | 29.6 | |||

| Neither in-laws or natal family | 63.0 | 52.5 | 64.4 | 70.4 | |||

| Number of children ever born | 1.9 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.1 | <0.001 | 0.312 | <0.001 |

| Completed grades of schooling (%) | <0.001 | 0.090 | <0.001 | ||||

| 0–7 grades | 38.6 | 23.1 | 40.1 | 50.6 | |||

| 8–12 grades | 47.1 | 55.6 | 47.0 | 38.9 | |||

| >12 grades | 14.3 | 21.3 | 12.9 | 10.5 | |||

| Schooling relative to wife (%) | 0.001 | 0.662 | 0.010 | ||||

| Less education | 24.4 | 19.4 | 25.2 | 27.8 | |||

| Same education | 49.5 | 45.6 | 51.2 | 50.0 | |||

| More education | 26.1 | 35.0 | 23.7 | 22.2 | |||

| Age relative to wife (%) | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.033 | ||||

| Younger | 11.0 | 6.9 | 11.1 | 14.8 | |||

| Same | 14.3 | 10.6 | 17.1 | 12.4 | |||

| Older | 72.9 | 81.3 | 71.0 | 68.5 | |||

| Don't Know | 1.8 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 4.3 | |||

| Household Economic Index (%) | 0.029 | 0.018 | 0.087 | ||||

| Lowest Tertile | 32.8 | 30.6 | 29.3 | 42.0 | |||

| Middle Tertile | 35.4 | 29.4 | 38.9 | 34.0 | |||

| Highest Tertile | 31.9 | 40.0 | 31.7 | 24.1 | |||

| Income relative to wife (%) | 0.001 | 0.218 | 0.012 | ||||

| More | 41.3 | 47.5 | 39.5 | 38.9 | |||

| Less | 10.2 | 13.8 | 10.5 | 6.2 | |||

| Same | 39.5 | 34.4 | 39.5 | 44.4 | |||

| Don't Know | 9.0 | 4.4 | 10.5 | 10.5 | |||

Exposed to both witnessing IPV against mother and physical maltreatment

Exposed to either witnessing IPV against mother or physical maltreatment, but not both

Exposed to neither witnessing IPV against mother nor physical maltreatment

Attitudes about and Perpetration of Physical IPV against Wives

More than one fourth of men reported to have ever perpetrated physical IPV against their wife (Table 2). A dose-response relationship between exposure to violence in childhood and IPV perpetration was apparent. More than one fourth of men agreed that a husband has good reason to hit his wife if she rudely argues with him (47.2%), has been unfaithful (46.5%), or neglects the children (25.7%). Compared to men exposed to neither form of violence in childhood, those exposed to one form less often found good reason to hit a wife if she goes out without telling him (5.1% vs. 8.6 %), and those exposed to both forms more often found good reason to hit a wife if she has been unfaithful (56.3% vs. 37.0%). Compared to men exposed to one form of violence in childhood, men exposed to both forms more often found good reason to hit a wife if she has been unfaithful (56.3% vs. 46.4%) or goes out without telling him (10.0% vs. 5.1%). Otherwise, men’s responses on the individual attitudinal items did not differ.

Table 2.

Prevalence of perpetrating physical IPV in adulthood and of finding 'good reason' for a husband to hit his wife in specific situations, overall and by type of exposure to violence in childhood, N=522 married men 18– 51 Years in My Hao district, Vietnam

| By exposure to violence in childhood: | P-Value | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N=522) | Botha (N=122) | Oneb (N=273) | Neitherc (N=127) | both vs. neither |

one vs. neither |

both vs. one |

|||||

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | ||||

| Lifetime Perpetration of Physical IPV | |||||||||||

| Yes | 28.1 | (24.7, 31.7) | 36.3 | (31.5, 41.3) | 31.1 | (26.7, 35.9) | 13.6 | (9.4, 19.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.037 |

| No | 72.0 | (68.3, 75.3) | 63.8 | (58.7, 68.5) | 68.9 | (64.1, 73.3) | 86.4 | (80.1, 90.6) | |||

| Finding Good Reason to Hit a Wife if: | |||||||||||

| She refuses to have sexual relations with him | 4.0 | (2.2, 7.0) | 1.3 | (0.5, 3.2) | 4.8 | (2.4, 9.3) | 4.9 | (2.6, 9.4) | 0.057 | 0.921 | 0.053 |

| She asks him whether he has other girlfriends | 3.7 | (2.3, 5.9) | 4.4 | (2.2, 8.7) | 3.0 | (1.4, 6.3) | 4.3 | (2.5, 7.5) | 0.979 | 0.094 | 0.479 |

| He finds out that she has been unfaithful | 46.5 | (41.9, 51.2) | 56.3 | (48.1, 64.1) | 46.4 | (40.4, 52.5) | 37.0 | (30.3, 44.4) | 0.001 | 0.054 | 0.019 |

| She goes out without telling him | 7.2 | (5.0, 10.1) | 10.0 | (5.8, 16.7) | 5.1 | (3.5,7.4) | 8.6 | (5.9, 12.6) | 0.627 | 0.017 | 0.040 |

| She neglects the children | 25.7 | (21.1, 31.0) | 30.6 | (23.3, 39.1) | 24.8 | (18.7, 32.0) | 22.8 | (18.9, 27.3) | 0.070 | 0.568 | 0.161 |

| She rudely argues with him | 47.2 | (42.0, 52.4) | 51.9 | (44.8, 58.9) | 47.0 | (39.7, 54.4) | 42.9 | (36.1, 49.9) | 0.069 | 0.368 | 0.210 |

| Overall | 0.016 | 0.002 | 0.113 | ||||||||

| Agree with none | 34.6 | (30.0, 39.5) | 30.6 | (23.9, 38.3) | 31.4 | (25.9, 37.5) | 45.1 | (37.4, 53.0) | |||

| Agree with 1–2 items | 45.7 | (42.3, 49.2) | 44.4 | (37.3, 51.7) | 51.5 | (47.2, 55.8) | 35.2 | (29.0, 42.0) | |||

| Agree with 3 or more items | 19.7 | (16.2, 23.7) | 25.0 | (18.9, 32.3) | 17.1 | (12.5, 22.9) | 19.8 | (15.7, 24.6) | |||

Exposed to both witnessing IPV against mother and physical maltreatment

Exposed to either witnessing IPV against mother or physical maltreatment, but not both

Exposed to neither witnessing IPV against mother nor physical maltreatment

Overall, 19.7% of men agreed that a husband has good reason to hit his wife in three or more situations (Table 2). Compared to men exposed to neither form of violence in childhood, men exposed to one or both forms more often agreed that a husband has at least one good reason to hit his wife (68.6% and 69.4% versus 55.0%).

Multivariate Results

Attitudes about IPV

Compared to men exposed to neither form of violence in childhood, men exposed to one or both forms had higher unadjusted proportional odds of reporting such attitudes (Model 1, Table 3). These associations changed little with adjustments for confounders and control mediators (Model 2). In Model 3, men’s perpetration of physical IPV was associated with 2.57 times the proportional odds of finding more good reasons for a husband to hit his wife, and exposure to violence in childhood was no longer significantly associated with attitudes about IPV. Men’s age, schooling, and household wealth were negatively associated with reporting more good reasons for wife hitting (Models 2 and 3). No other covariates were associated with men’s attitudes about IPV.

Table 3.

Odds ratios from ordered logistic models of the relationship between childhood exposure to violence and attitudes about IPV against women (0, 1–2, 3–6 good reasons to hit a wife), N=522 married men 18–51 years in My Hao district, Vietnam

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | p | OR | (95% CI) | p | OR | (95% CI) | p | |

| Exposure to Violence in Childhood | |||||||||

| Experienced or witnessed violence (ref: neither) | 1.41 | (1.03, 1.93) | * | 1.43 | (1.03, 2.00) | * | 1.21 | (0.86, 1.69) | |

| Experienced and witnessed violence (ref: neither) | 1.74 | (1.13, 2.67) | ** | 1.66 | (1.05, 2.64) | * | 1.33 | (0.83, 2.14) | |

| Lifetime Perpetration of IPV in Adulthood | |||||||||

| Perpetrated physical IPV as an adult (ref: no) | 2.57 | (1.93, 3.41) | *** | ||||||

| Covariates/Control Mediators | |||||||||

| Childhood residence other (ref: same town) | 0.58 | (0.32, 1.07) | 0.59 | (0.31, 1.14) | |||||

| Age, years | 0.96 | (0.94, 0.98) | *** | 0.96 | (0.94, 0.98) | *** | |||

| Living with in-laws or natal family (ref: neither) | 0.80 | (0.58, 1.10) | 0.85 | (0.61, 1.19) | |||||

| Number of children ever born | 1.05 | (0.89, 1.22) | 1.05 | (0.90, 1.23) | |||||

| Completed grades of schooling (ref: 0–7) | |||||||||

| 8–12 | 0.84 | (0.62, 1.15) | 0.85 | (0.64, 1.13) | |||||

| >12 | 0.49 | (0.33, 0.75) | *** | 0.55 | (0.36, 0.84) | ** | |||

| Schooling relative to wife (ref: same) | |||||||||

| More | 1.04 | (0.74, 1.44) | 0.98 | (0.72, 1.33) | |||||

| Less | 0.82 | (0.64, 1.05) | 0.80 | (0.63, 1.02) | |||||

| Age relative to wife (ref: same age) | |||||||||

| Younger | 1.42 | (0.83, 2.42) | 1.45 | (0.83, 2.55) | |||||

| Older | 1.20 | (0.80, 1.81) | 1.29 | (0.87, 1.93) | |||||

| Household Economic Index (ref: middle tertile) | |||||||||

| Lowest tertile | 1.03 | (0.78, 1.36) | ** | 1.00 | (0.76, 1.33) | *** | |||

| Highest tertile | 0.60 | (0.44, 0.81) | 0.57 | (0.42, 0.77) | |||||

| Income relative to wife (ref: same) | |||||||||

| More | 1.13 | (0.72, 1.76) | 1.11 | (0.71, 1.74) | |||||

| Less | 1.39 | (0.76, 2.54) | * | 1.36 | (0.77, 2.40) | ||||

Note. Models also control for “don’t know” responses for age and income relative to wife.

p ≤ 0.05;

p ≤ 0.01; p ≤ 0.001

Perpetration of IPV

Compared to men exposed to neither form of violence in childhood, men exposed to one or both forms had higher unadjusted odds of ever perpetrating physical IPV (Model 1, Table 4). These associations strengthened with adjustments for confounders and control mediators (Model 2). In Model 3, men who found some or many good reasons for wife hitting had higher adjusted odds of ever perpetrating physical IPV than those who found no good reason; yet, both categories of exposure to violence in childhood remained significantly associated with the perpetration of IPV. Otherwise, living with in-laws and being older than ones wife were the only variables significantly associated with perpetration.

Table 4.

Odds ratios from logistic models of the relationship between childhood exposure to violence and lifetime perpetration of physical IPV against women, N=522 married men 18–51 years in My Hao district, Vietnam

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | p | OR | (95% CI) | p | OR | (95% CI) | p | |

| Exposure to Violence in Childhood | |||||||||

| Experienced or witnessed violence (ref: neither) | 2.88 | (1.91, 4.34) | *** | 3.28 | (2.15, 4.99) | *** | 3.18 | (2.03, 5.00) | *** |

| Experienced and witnessed violence (ref: neither) | 3.62 | (2.38, 5.51) | *** | 4.56 | (2.90, 7.17) | *** | 4.30 | (2.63, 7.03) | *** |

| Attitudes in Adulthood about IPV against Women | |||||||||

| Found some (1–2) good reasons to hit a wife (ref:none) | 2.38 | (1.73, 3.26) | *** | ||||||

| Found many (3–6) good reasons to hit a wife (ref:none) | 4.50 | (2.74, 7.41) | *** | ||||||

| Covariates/Control Mediators | |||||||||

| Childhood residence other (ref: same town) | 0.68 | (0.36, 1.28) | 0.78 | (0.41, 1.48) | |||||

| Age, years | 1.01 | (0.98, 1.03) | 1.02 | (0.99, 1.05) | |||||

| Living with in-laws or natal family (ref: neither) | 0.68 | (0.51, 0.92) | ** | 0.71 | (0.50, 1.01) | * | |||

| Number of children ever born | 0.88 | (0.67, 1.16) | 0.85 | (0.63, 1.14) | |||||

| Completed grades of schooling (ref: 0–7) | |||||||||

| 8–12 | 0.87 | (0.60, 1.25) | 0.95 | (0.68, 1.32) | |||||

| >12 | 0.49 | (0.30, 0.78) | ** | 0.59 | (0.37, 0.95) | * | |||

| Schooling relative to wife (ref: same) | |||||||||

| More | 1.28 | (0.86, 1.91) | 1.32 | (0.99, 1.76) | |||||

| Less | 1.20 | (0.89, 1.62) | 1.28 | (0.88, 1.86) | |||||

| Age relative to wife (ref: same age) | |||||||||

| Younger | 1.18 | (0.73, 1.93) | 1.06 | (0.64, 1.77) | |||||

| Older | 0.74 | (0.51, 1.07) | 0.69 | (0.48, 1.00) | * | ||||

| Household Economic Index (ref: middle tertile) | |||||||||

| Lowest tertile | 2.03 | (0.63, 6.59) | 2.37 | (0.66, 8.48) | |||||

| Highest tertile | 1.18 | (0.89, 1.58) | 1.17 | (0.88, 1.56) | |||||

| Income relative to wife (ref: same) | |||||||||

| More | 1.20 | (0.73, 1.95) | 1.36 | (0.86, 2.14) | |||||

| Less | 1.25 | (0.92, 1.70) | 1.23 | (0.89, 1.68) | |||||

Note. Models also control for “don’t know” responses for age and income relative to wife.

p ≤ 0.05;

p ≤ 0.01; p ≤ 0.001

DISCUSSION

We explored, in the rapidly changing context of rural Vietnam, how men’s exposure to violence in childhood is related to their attitudes about and perpetration of IPV against wives. In models adjusted for confounders and control mediators, men who witnessed physical IPV against their mother and/or who were hit or beaten in childhood by a parent or other adult relative had higher proportional odds of finding more good reasons for a husband to hit his wife. In another study in Vietnam, women witnessing father-to-mother violence in childhood also more often justified IPV in adulthood (not adjusting for confounders) [31]. Our study extends these findings by showing consistencies across gender in the influence of parental violence in childhood on attitudes about IPV. Yet, these associations became insignificant when men's perpetration of physical IPV was added, suggesting that men who perpetrate IPV are more likely to justify it than their counterparts, independent of their childhood exposure to violence.

In models adjusted for confounders and control mediators, men who witnessed and/or experienced violence in childhood had higher adjusted odds of perpetrating IPV. These results corroborate those from South Africa [36] and Uganda [37]. Also, consistent with research in the U.S. [26], men’s attitudes about IPV modestly attenuated the associations between men’s exposure to violence in childhood and their perpetration of IPV.

Limitations

Because our study was cross-sectional, all findings should be interpreted as associational. We did not measure all forms, nor the frequency and severity, of witnessing IPV and child maltreatment. Thus, our estimated effects likely are lower bounds of the true effects. Still, meta-analytic reviews suggest that experiencing corporal punishment in childhood is associated with various forms of violence in adulthood [25]. Too few men (n=18) had witnessed IPV without experiencing child maltreatment to disentangle their separate effects on the outcomes (results available upon request). The attitudinal questions on IPV against wives neither capture degrees of justification nor contextualized the situations by portraying the wife as “at fault” or “not at fault” [38]. Still, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses of the 10 attitudinal items showed that the 6 retained items reflected well a unidimensional construct [34]. Validation of this scale in urban Vietnam and elsewhere is warranted.

Contributions

Our study is one of the few examining violence in childhood, attitudes about IPV, and IPV perpetration in a probability sample of men in a low-income setting. Also, we assessed exposure to two forms of violence in childhood. Because these forms of violence often co-occur, assessing only one would inflate its association with attitudes and perpetration [39].

Future Directions

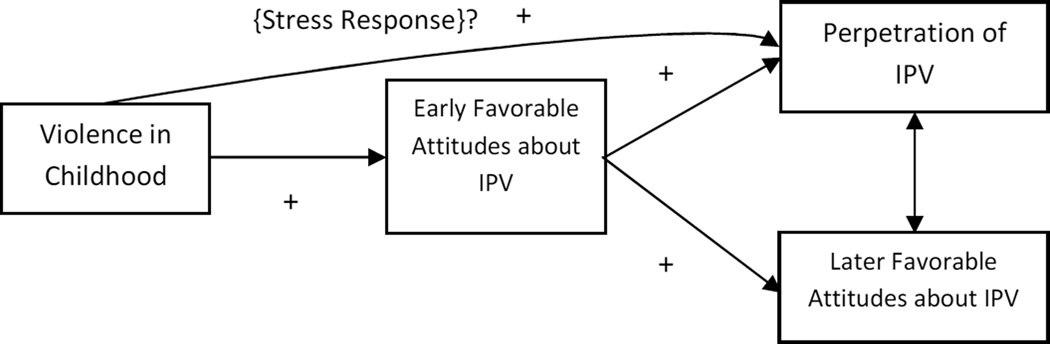

Our findings suggest the need address exposure to violence in childhood, before IPV perpetration occurs. They also suggest pathways from violence in childhood that warrant longitudinal study (Figure 1). Namely, exposure to violence in childhood may be associated with a higher risk of perpetrating IPV directly, and indirectly through justifying IPV. In turn, the perpetration of IPV may lead to ex post facto justification of it. The “direct” pathway from violence in childhood to perpetration in our study suggests altered stress responses [4], which may elevate the risk of perpetrating IPV. Longitudinal studies are needed to disentangle the relationship between attitudes about and perpetration of IPV over time, and to assess whether trauma-associated stress in childhood underlies these relationships.

Figure 1.

Violence in Childhood: Summary Pathways of Influence on Attitudes about and Perpetration of IPV

Acknowledgements

We thank the Center for Creative Initiatives in Health and Population (CCIHP) and the local health authority of My Hao district for their outstanding partnerships; CCIHP collaborators Ms. Vu Song Ha and Ms. Quach Trang; Dr. Sarah Zureick-Brown, a former post-doctoral fellow in the Hubert Department of Global Health at Emory University; and all of the study participants for their time, effort, and dedication to this project.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH research grant 5R21HD067834-01/02 (PIs KM Yount and SR Schuler) and the Hubert Department of Global Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University.

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- IPV

intimate partner violence

- Witnessing IPV

witnessing IPV against mother

- Experiencing physical maltreatment

hitting or beating by a parent or adult relative

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saltzman LE, Fanslow JL, McMahon PM, et al. Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements: Version 1.0. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellsberg M, Jansen HA, Heise L, et al. Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet. 2008;371(9619):1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carbone-López K, Kruttschnitt C, Macmillan R. Patterns of intimate partner violence and their associations with physical health, psychological distress, and substance use. Public Health Rep. 2006;121(4):382. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yount KM, DiGirolamo AM, Ramakrishnan U. Impacts of domestic violence on child growth and nutrition: A conceptual review of the pathways of influence. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72(9):1534–1554. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weldon SL. Protest, policy, and the problem of violence against women: A cross-national comparison. University of Pittsburgh Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.García-Moreno C, Stöckl H. Protection of sexual and reproductive health rights: Addressing violence against women. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;106(2):144–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yount KM, VanderEnde K, Zureick-Brown S, et al. Measuring Attitudes about Women’s Recourse in Response to IPV: The ATT-RECOURSE Scale. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0886260513511536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flood M, Pease B. Factors influencing attitudes to violence against women. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2009;10(2):125–142. doi: 10.1177/1524838009334131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon TR, Anderson M, Thompson MP, et al. Attitudinal acceptance of intimate partner violence among US adults. Violence Vict. 2001;16(2):115–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yount KM. Resources, Family Organization, and Domestic Violence Against Married Women in Minya, Egypt. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(3):579–596. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rani M, Bonu S. Attitudes Toward Wife Beating: A Cross-Country Study in Asia. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24(8):1371–1397. doi: 10.1177/0886260508322182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lichter EL, McCloskey LA. The effects of childhood exposure to marital violence on adolescent gender-role beliefs and dating violence. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28(4):344–357. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markowitz FE. Attitudes and family violence: Linking intergenerational and cultural theories. Journal of Family Violence. 2001;16(2):205–218. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yount KM, Li L. Women's“justification” of domestic violence in Egypt. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71(5):1125–1140. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yount KM, Halim N, Hynes M, et al. Response effects to attitudinal questions about domestic violence against women: A comparative perspective. Social Science Research. 2011;40:873–884. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holden GW. Children Exposed to Domestic Violence and Child Abuse: Terminology and Taxonomy. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2003;6(3):151–160. doi: 10.1023/a:1024906315255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.United Nations Children's Fund, Children UNS-GsSoVA, International TBS, et al. Behind Closed Doors: The Impact of Domestic Violence on Children. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. New York: General Learning Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin SL, Moracco KE, Garro J, et al. Domestic violence across generations: findings from northern India. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31(3):560–572. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wareham J, Boots DP, Chavez JM. A test of social learning and intergenerational transmission among batterers. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2009;37(2):163–173. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gil-González D, Vives-Cases C, Ruiz MT, et al. Childhood experiences of violence in perpetrators as a risk factor of intimate partner violence: a systematic review. Journal of public health. 2008;30(1):14–22. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdm071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fry D, McCoy A, Swales D. The Consequences of Maltreatment on Children’s Lives: A Systematic Review of Data From the East Asia and Pacific Region. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2012;13(4):209–233. doi: 10.1177/1524838012455873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abramsky T, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C, et al. What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Bmc Public Health. 2011;11 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wubs AG, Aaro LE, Mathews C, et al. Associations Between Attitudes Toward Violence and Intimate Partner Violence in South Africa and Tanzania. Violence Vict. 2013;28(2):324–340. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.11-063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gershoff ET. Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: a meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychol Bull. 2002;128(4):539. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin X, Eagle M, Yoshioka M. Early exposure to violence in the family of origin and positive attitudes towards marital violence: Chinese immigrant male batterers vs. controls. J Fam Violence. 2007;22(4):211–222. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uthman OA, Moradi T, Lawoko S. Are Individual and Community Acceptance and Witnessing of Intimate Partner Violence Related to Its Occurrence? Multilevel Structural Equation Model. PloS one. 2011;6(12):e27738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.United Nations Children's Fund. Measuring and monitoring child protection systems: proposed core indicators for the east asia and pacific region. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 29.General Statistics Office. "Keeping silent is dying". Vietnam: Ha Noi; 2010. Results from the National Study on Domestic Violence Against Women in Viet Nam. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rydstrøm H. Masculinity And Punishment: Men's upbringing of boys in rural Vietnam. Childhood. 2006;13(3):329–348. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vung ND, Krantz G. Childhood experiences of interparental violence as a risk factor for intimate partner violence: a population-based study from northern Vietnam. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(9):708–714. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.076968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yount KM, VanderEnde KE, Zureick-Brown S, et al. Measuring attitudes about women’s recourse after exposure to intimate partner violence: The ATT-recourse scale. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2013:1–27. doi: 10.1177/0886260513511536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.(GSO); GSO, (NIHE); NIoHaEV, Macro O. Vietnam Population and AIDS Indicator Survey 2005. Calverton, Maryland, USA: GSO, NIHE, and ORC Macro; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yount KM, VanderEnde KE, Zureick-Brown S, et al. Measuring Attitudes about Intimate Partner Violence against Women: The ATT-IPV Scale. Demography forthcoming. doi: 10.1007/s13524-014-0297-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zach M, Singleton J, Satterwhite C. Collinearity macro (SAS) Department of Epidemiology RSPH at Emory Univeristy; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gass JD, Stein DJ, Williams DR, et al. Gender Differences in Risk for Intimate Partner Violence Among South African Adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(14):2764–2789. doi: 10.1177/0886260510390960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Speizer IS. Intimate Partner Violence Attitudes and Experience Among Women and Men in Uganda. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25(7):1224–1241. doi: 10.1177/0886260509340550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schuler SR, Lenzi R, Yount KM. Justification of Intimate Partner Violence in Rural Bangladesh: What Survey Questions Fail to Capture. Stud Fam Plann. 2011;42(1):21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2011.00261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osofsky JD. Prevalence of Children's Exposure to Domestic Violence and Child Maltreatment: Implications for Prevention and Intervention. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2003;6(3):161–170. doi: 10.1023/a:1024958332093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]