Abstract

Purpose

To describe the immune alterations associated with, age related macular degeneration (AMD). Based on these findings, to offer an approach to possibly prevent the expression of late disease.

Design

Perspective

Methods

Review of the existing literature dealing with epidemiology, models, and immunologic findings in patients.

Results

Significant genetic associations have been identified and reported, but environmentally induced (including epigenetic) changes are also an important consideration. Immune alterations include a strong interleukin-17 family signature as well as marked expression of these molecules in the eye. Oxidative stress as well as other homeostatic altering mechanisms occurs throughout life. With this immune dysregulation there is a rationale for considering immunotherapy. Indeed immunotherapy has been shown to affect the late stages of AMD.

Conclusion

Immune dysregulation appears to be an underlying alteration in AMD as in other diseases thought to be degenerative and due to aging. Parainflammation and immunosensescence may importantly contribute to the development of disease. The role of complement factor H still needs to be better defined but in light of its association with ocular inflammatory conditions such as sarcoidosis, it does not appear to be unique to AMD but rather may be a marker for retinal pigment epithelium function. With the strong interleukin-17 family signature and the need to treat early on in the disease process, oral tolerance may be considered to prevent disease progression.

Keywords: Age related macular degeneration, oral tolerance, Epigenetics, acquired and innate immunity

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) continues to be the most common cause of irreversible central vision loss in developed countries, affecting 25 to 35 million people worldwide.1–3 It has been estimated that 1.75 million patients have late AMD in the United States, defined as geographic atrophy or neovascular AMD in at least one eye, and an additional 7.3 million have at least 1 large drusen.4 Population based estimates indicate that late AMD will affect over 3 million people in the United States by 2020.3 A putative role for the immune system in the pathogenesis of AMD has been suggested since the 1980s and more recently.5,6 Clearly a better understanding of the mechanisms leading to this disorder is of great public health import. This review will discuss the myriad observations that can support an unified hypothesis for immune mediation of AMD and a possible therapeutic strategy.

What does the Epidemiology of Age Related Macular Degeneraton tell us?

Recent data from more than a decade of follow-up of participants in the Age-Related Eye disease Study (AREDS) demonstrated an increased risk of developing AMD associated with medium sized drusen, but not small drusen <65 microns in diameter (early AMD). In addition, the presence of medium drusen, but not small drusen, increased the risk of progression to large drusen and pigmentary changes (intermediate AMD), putting individuals at risk for progression to late AMD7,8 This suggests that small drusen may be necessary but not sufficient for the development of late AMD. However, once medium size drusen (between 65 and 125 microns) develop the risk of progression to large drusen, pigmentary changes and eventually late AMD increases. Persons with bilateral medium size drusen have a 40% to 50% 5-year risk of developing large drusen and a 20% 5-year risk of developing late AMD, compared with a less than 5% risk for those with no drusen or small drusen.7 Thus these data support the notion that the disease process begins much earlier than the when it becomes clinically problematic in the 7th and 8th decade of life.

Genetics vs the environment

Genetic and genomic approaches, such as family linkage analysis and genome-wide association studies, have revealed important genetic contributions to AMD pathogenesis. A significantly higher concordance rate of AMD in monozygotic twins than in dizygotic twins and in families further corroborates a genetic predisposition to AMD. Recent genetic meta-analysis has confirmed 19 loci (principally complement factor H (CFH), serine protease HTRA1/age related maculopathy susceptibility protein 2) that account for up to than 50% of the heritability of AMD susceptibility. Nevertheless, it remains unclear how exactly these genetic risk factors contribute to the pathogenesis of disease. Further they may reflect a predisposition to a loosening of the normal down regulatory immune environment (DIE) of the eye, since other inflammatory disorders have a similar association (see below).

Non-genetic risk factors such as smoking, dietary intake and BMI have been associated with development of AMD. Interestingly, Gottfredsdottir et al9 report that the concordance of AMD between couples, who are genetically unrelated but share long-term environmental exposure, is as high as 70.2%, which is significantly higher than the 0.25% chance that two aged Caucasians both have late AMD. Therefore, in addition to genetic susceptibility, environmental modulators may also play a crucial role in AMD etiology. Furthermore, there is compelling animal data to support such environmental modulation on the backdrop of genetic susceptibility. Administering high omega-3 fatty acid diets to chemokine deficient mice that show retinal lesions akin to the pathology of AMD reverses such lesions and suppresses inflammation, perhaps through a reduction in arachadonic acid metabolism.10 It is interesting to speculate that non-inheritable non-genetic environmental influences beyond deoxyribonucleic acid could be key to the control of AMD pathogenesis, and this so-called epigenetic regulation may be an important area for further investigation, in particular through the interrogation of DNA methylation and histone modification patterns in AMD patients.

An aging retina vs an aging immune system

Age is the most significant risk factor for AMD. Despite an increased understanding of metabolic and physiologic changes that occur with age we still do not know the exact changes that cause disease or indeed drive disease progression. Throughout life, tissue resident immune cells and supporting stromal cells (e.g. retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and glia) in retina and choroid are capable of controlling as well as mounting immune responses, which results in preservation of cellular function by adequately dealing with danger signals and maintaining health. In the aging eye, and especially at the level of the RPE, there is an accumulation of oxidative products such as reactive oxygen species, further increasing oxidative stress, as well as the accumulation of lipofuscin and A2E, which presumably alter the metabolism and health of the RPE.11 This increasing stress could activate the cell to further contribute to tissue damage.12 The increasing “stress” needs to be counterbalanced by mechanisms that attempt to return the cell to a homeostatic state. One such mechanism is parainflammation, first proposed by Medzhitov13 and well described in the eye.14 Medzhitov has described it as “… a tissue adaptive response to noxious stress or malfunction and has characteristics that are intermediate between basal and inflammatory states”13. Here the immune system’s reparative mechanisms are theorized to be a basic protective mechanism through life. This concept has been furthered in the eye by Schwartz et al, who have further speculated about the role of protective autoimmunity of T cells, yet another putative reparative mechanism.15

The association of CFH with AMD is well founded in many studies. While CFH variants have been consistently reported to be associated with AMD in man, they have also been reported as being associated with two ocular inflammatory disorders involving the retinal pigment epithelium, multifocal choroiditis16 and posterior ocular sarcoidosis.17 Animal models have been used as a platform for mechanistic studies. They can be informative as to the individual components of the immune response to the eye. Following the demonstration of complement deposition that occurs in AMD18, attention at the mouse level has focused on whether manipulation of the immune system delivers phenotypes similar to AMD. Animal studies in AMD were initially confounded by the presence of an independent retinal degeneration mutation (Rd8) in many of the AMD models used19 and by the lack of a macula and the binuclear nature of the rodent RPE, unlike that of humans. However, there remains strong evidence to support the concept that dysregulation of the immune response causes AMD-like phenotypes.20–24 Other genetic associations with AMD also point toward a key role for immunity. Serine protease HTRA1/age related maculopathy susceptibility protein 2 genes are critical for the production of transforming growth factor, which plays an important role in the control of inflammation and interacts with matricellular proteins such as thrombospondin.25

All this needs to be put in the context of an aging systemic immune system. Increasing age results in what has been described as immunosenescense,26,27 with reduced lymphocyte numbers, as well as an enrichment of myeloid cells in peripheral blood and lymphoid tissue, an increased number of memory T cells (both CD4+ and CD8+), especially Th17 cells.28,29 In addition, there are changes in the innate immune system, such as reduced phagocytosis and an increased production of proinflammatory cytokines including interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 in aged macrophages, with the potential that this will reduce their ability to clear extracellular debris and apoptotic cells in vivo and as well induce a shift in macrophage subtypes from the “M2” to the “M1” subtype.30 It has been suggested that immunosenescence may in part be driven by a persistent cytomegalovirus infection, which although not causing overt clinical disease, is continually activating the immune system. Indeed some older individuals have an inordinately large number of circulating CD4 cells that are directed against CMV.31 The immune dynamics of a degenerating retina, as shown in animal models, includes an alteration in RPE function and both activation and infiltration of innate immune cells, resulting in a para-inflammatory environment whereby homeostasis is lost and pathology is exacerbated.14,20,32,33.

Alterations in Innate and adaptive immune responses with aging

With the failure of parainflammation in aging, it is plausible that following RPE release of small drusen and new antigen presentation, retinal or sub-retinal immune surveillance could be activated. This could lead to consequent activation of T-cell mediated adaptive immune responses in the periphery, including B-cell activation and antibody production and could eventually lead to progression down the path of developing medium drusen, large drusen and eventually late AMD.

In support of a role for such adaptive immune responses in the development of AMD are recent reports in humans that suggest complement C5a promotes Th17 cell mediated inflammation, providing a potential link between innate and adaptive immunity in the pathogenesis of AMD.34 In addition, although innate immune responses are often observed at non-ocular infectious sites, identification of elevated cytokines circulating in the blood as well as the retina in AMD patients suggests that AMD may be systemically driven through memory T-cell responses. T-cell involvement seems to be quite prominent, with evidence of circulating interleukin-22 and inteleukin-17 in the sera of AMD patients early, by the 6th decade, before any indication of visual disturbance. We also have seen that with enhanced C5a expression on T-cells, greater amounts of Iinterleukin-17 are produced. Overexpression of the Interleukin 17 receptor C in the retina is seen.35 Also noted is an anamnestic response in some AMD patients’ T cells to fragments of the retinal S-antigen, similar to that seen in uveitis patients (unpublished data). Similarly, the observations of autoantibodies (including anti-retinal antibodies) in AMD patients is potentially important36 and their presence offers evidence that assessment of the adaptive immune response may provide biomarkers for subgroups of patients at risk of AMD progression, or targets for novel therapies.

Immunotherapy: what could be considered?

Corticosteroids have been used to treat AMD, without an observed clinically important effect.37. Theoretically they would have the dual benefit of controlling the immune response and regulating tight junctions to shore up the blood-ocular barrier, and prevent extravasation of fluid into the retina.38 The lack of effect of corticosteroids39 is perhaps not surprising given the strong inteleukin-17 signature in AMD, a characteristic of immunosenescence. In addition, this link with interleukin-17 is critical as memory CD4+ T cells expressing interleukin-17 have been shown to be steroid resistant in other inflammatory diseases40,41 including patients with posterior uveitis, where in vitro corticosteroid sensitivity is highly correlated with clinical responses to treatment.42 Almost every aspect of the complement cascade is being tested as a possible therapy for late AMD, including C3 inhibitors, an aptamer based C5 inhibitor, a C5 antibody, an anti-Factor D antibody, a complement factor B inhibitor and a peptidomimetic C5a receptor inhibitor and others. While anti-Factor D antibody results suggest some activity, trials still await full evaluation. Although some may prove effective, these interventions do not take account of the possible role of adaptive immunity, nor associated systemic immune dysregulation. In addition it is unclear whether these mechanisms are operative in all patients, and at what stage of disease.

In a small, randomized, unmasked proof of principle study in which AMD patients with choroidal neovascularization needing repeated injections of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy patients were randomly assigned to 4 groups standard of care alone, intravenous daclizumab (directed against CD25, the alpha subunit of the IL-2 receptor), intravenous infliximab, or oral rapamycin (a macrocyclic lactone produced by Streptomyces hyproscopicus, also known as sirolimus).43 All four groups had monthly clinical and OCT evaluations for evidence of intraretinal or subretinal fluid. Patients with fluid received intravitreal anti-VEGF injections monthly. Comparing the number of anti-VEGF injections, there was a decrease in the number of injections required in patients given daclizumab or rapamycin, whereas no apparent decrease was noted for either the infliximab or the standard of care group. This proof of principle study thus suggested (but did not prove) that immunosuppressive therapy could alter the course of even late stage disease. Although there have been many clinical trials of treatments for late AMD, no one to date has tested a therapeutic intervention, other than supplements, to slow or prevent progression of AMD the expression of the disease. An ideal preventive therapy would start before ocular symptoms begin, be non-toxic, have specificity to retinal tissue, be targeted to the right patients at the right time. One such approach would be to reduce systemic inflammation. It will not be practical to alter immune responses in patients with biologics for several decades, as the cost and possible toxic effects prohibit such an approach. If an immunologic approach is to be tested, other methods must be sought.

How can we put this together?

There is ample information in the literature to support the notion that AMD, as with many so-called degenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and atherosclerosis, has an important immune component to the underlying mechanisms of disease development and progression. Even though there are variable outcomes of the reports to date, there still remains enough clinical and experimental support of the concept of immune engagement which goes far beyond CFH. Indeed, evidence supporting the adaptive immune system is directly implicated in both mouse23 and man.34,35 Further it will almost assuredly become clear that the disorder that we recognize as AMD is probably not one disease and is the end result of several immune (and other) pathways.

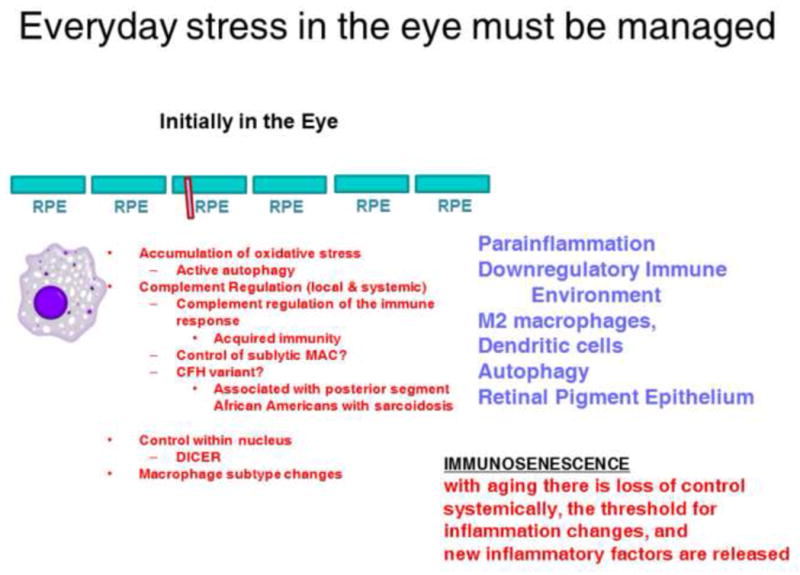

Based on the information gathered to date, is it possible to offer a cohesive concept of immune mediation leading to the AMD? There certainly appears to be and a proposed hypothesis can be seen in the two figures. As we progress through life the eye is subject to a great deal of stress. These include constant oxidative stress, active autophagy with its good and negative results, and in those genetically prone a loss of competent complement regulation as well as dicer alterations leading to changes in micro-ribonucleic acid control44. For most of our lifespan parainflammation and the downregulatory immune environment of the eye are able to control these stresses, removing debris, and restoring homeostasis with a continuation of normal ocular activity. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The eye maintains homeostasis in part by parainflammation and the down regulatory immune environment.

Abbreviations: DICER= Ribonucleic acid III endoribonuclease that cleaves double-stranded ribonucleic acid. RPE= Retinal Pigment Epithelium. MAC=Membrane Attack Complexes;

However, with aging, immunosensescence changes this equilibrium, and perhaps with the extrusion of small drusen into the extracellular space, this equilibrium is altered, with loss of systemic control of many aspects of the immune system, and the release of new inflammatory factors. The result of this transition can be seen in Figure 2, whereby a systemic change in the immune system results in an alteration in the eye. Parainflammation and other mechanisms have lost control. Pro-inflammatory molecules (perhaps interleukin-22) now enter the eye and a marked change occurs in the ocular immune environment. M1 macrophages now enter the eye in larger numbers leading to T cell involvement and possible anamnestic responses to S-antigen fragments or other antigens. With this injury and loss of RPE cells one would expect complement activation, deposition of complement membrane attack complexes (MAC), and further injury to both the RPE and neighboring tissues. This would be akin to what is seen in systemic lupus erythematosus where inflammation with large numbers of cells does not occur.

Figure 2.

With immunosensescence the equilibrium has been lost and age related changes occur.

Abbreviations: IL-17RC= Interleukin 17 Receptor C; AMD= Age Related Macular Degeneration; CXCR= C-X-C chemokine receptor

How could this proposal translate into a new treatment? One approach would be tolerance therapy, which re-aligns adaptive immunity by suppressing T cell responses. This can be achieved via the transfer of cells that regulate the immune system45, or via low dose administration (oral, nasal, subcutaneous) of antigen that suppresses a previous antigen driven response. A strategy with potential to fulfill our ideal criteria would therefore be oral tolerance. The immune system of the gut (GALT or gut-associated lymphoid tissue) is the largest collection of lymphoid tissue in the body, and using this system to down-regulate immune responses has been studied for some time.46 This interest has been further enhanced with the discovery of the importance of the microbiome.47 Oral tolerance has been defined as the “… physiologic induction of tolerance that occurs in the GALT and more broadly at other mucosal surfaces such as the respiratory tract”.46 The notion of T regulatory cells produced in the gut migrating to the site where the ingested antigen is found in the body has been noted. It has been used to treat several animal models of inflammatory disease and has also been successful in humans, in both children and adults, including for human uveitis where patients were tapered off their immunosuppressive medications more readily with no side effects after oral tolerance therapy.48,49,50–52

It would seem therefore that this therapy could be directed towards preventing progression of AMD. It may be better suited to treating early AMD than treating the later stages of the disease. Oral tolerance provides an attractive therapeutic concept that could be harnessed in those patients with the target and biomarker signatures that would signify likelihood to respond. Patients identified with high circulating IL-17 family cytokines and medium drusen could potentially begin the oral administration of such an antigen.

AMD appears to sit within the sphere of other systemic diseases with an organ specific expression. We will learn from other subspecialties, as they will from us, about the effects of systemic interventions in treating these diseases of aging, which are so commonly seen in the Developed World and increasingly seen in Developing Countries. We believe that, as AMD becomes better classified with an improved understanding of its pathogenesis beyond CFH; other therapeutic avenues will certainly emerge.

Acknowledgments

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest and the following were reported.

Funding/Support. Support for all the NIH authors came from intramural funds. For ADD, RWJL, this work was partly supported by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre based at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and University College London Institute of Ophthalmology. The views expressed are those of the author(s) (R.L., A.D.D.) and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health

Biographies

Frederick Ferris III MD is the Clinical Director and Director of the Division of Epidemiology and Clinical Research at the National Eye Institute (NEI). After graduating from Princeton University he completed all his medical training at Johns Hopkins. He is a board certified ophthalmologist and epidemiologist. He came to NEI in 1973 and has been involved in many clinical trials including the Diabetic Retinopathy Study, the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study and the Age-Related Eye Disease Study.

Robert Nussenblatt MD MPH is the Chief of the Laboratory of Immunology at the National Eye Institute and Associate Director of the trans-NIH Center for Human Immunology. His interest is in translational and clinical immunology. Many trainees have gone on to assume leadership positions in Academia and in Industry. He has co-authored over 500 publications and a standard text on uveitis. He is listed in “Best Doctors in America” and “Top Ophthalmologists in the United States”.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures. ADD is a consultant for Novartis and received payment for lectures from Abbvie. RWJL is a consultant for Roche-Genentech. Patents for ADD and RWJL are through the University of Bristol and NIH. NIH Patents for RBN through the University of Bristol and NIH.

Contributions of the authors. Conception and design- RBN, FF, HNS. Analysis and interpretation- RBN, FLF, EC. Writing article- RBN, ADD, HNS, EC, RWJL, BL, LW. Critical revision of the article- RBN, RWJL, FLF, EC, HNS, ADD. Final approval of the article- RBN, ADD, HNS, EC, RWJL, BL, LW, FLF. Data Collection- RBN, FLF, HNS. Provision of Materials, etc- RBN, FLF. Statistical expertise- FLF. Obtaining funding- RBN, FLF. Literature search- RBN, RWJL, FLF, HNS, ADD, LW, BL. Administrative support, etc- RBN, FLF

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.United Nations. World Population Prospects: the 2000 Review. 2001 http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/wpp2000/highlights.pdf. Published February 28, 2001.

- 2.World Health Organization. Prevention of Blindness and Visual Impairment. [Accessed September 26, 2013];Priority Eye Diseases. 2012 http://www.who.int/blindness/causes/priority/en/index8.html.

- 3.Congdon N, O’Colmain B, Klaver CC, et al. Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004 Apr;122(4):477–485. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman DS, O’Colmain BJ, Munoz B, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004 Apr;122(4):564–572. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penfold PLKM, Sarks SH. Senile macular degeneration: the involvement of immunocompetent cells. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1985;223:69–76. doi: 10.1007/BF02150948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parmeggiani F, Romano MR, Costagliola C, et al. Mechanism of inflammation in age-related macular degeneration. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:546786. doi: 10.1155/2012/546786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chew EYCT, Agrón E, Sperduto RD, SanGiovanni JP, Davis MD, Ferris FL, III For the Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. Ten-Year Follow-up of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study. AREDS Report No. 36. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014 Jan 2; doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.6636. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study System for Classifying Age-related Macular Degeneration From Stereoscopic Color Fundus Photographs: The Age-Related Eye Disease Study Report Number 6. Amer J Ophthalmol. 2001;132:668–681. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottfredsdottir MS, Sverrisson T, Musch DC, Stefansson E. Age related macular degeneration in monozygotic twins and their spouses in Iceland. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1999 Aug;77(4):422–425. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1999.770413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuo J, Ross RJ, Herzlich AA, et al. A high omega-3 fatty acid diet reduces retinal lesions in a murine model of macular degeneration. Am J Pathol. 2009 Aug;175(2):799–807. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenney MC, Chwa M, Atilano SR, et al. Mitochondrial DNA variants mediate energy production and expression levels for CFH, C3 and EFEMP1 genes: implications for age-related macular degeneration. PloS one. 2013;8(1):e54339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson OA, Finkelstein A, Shima DT. A2E induces IL-1ss production in retinal pigment epithelial cells via the NLRP3 inflammasome. PloS one. 2013;8(6):e67263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008 Jul 24;454(7203):428–435. doi: 10.1038/nature07201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu H, Chen M, Forrester JV. Para-inflammation in the aging retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009 Sep;28(5):348–368. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz M, Shechter R. Systemic inflammatory cells fight off neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010 Jul;6(7):405–410. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrara DC, Merriam JE, Freund KB, et al. Analysis of major alleles associated with age-related macular degeneration in patients with multifocal choroiditis: strong association with complement factor H. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008 Nov;126(11):1562–1566. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.11.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson IA, Liu B, Sen HN, et al. Association of complement factor H tyrosine 402 histidine genotype with posterior involvement in sarcoid-related uveitis. Am j Ophthalmol. 2013 Jun;155(6):1068–1074. e1061. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson DH, Radeke MJ, Gallo NB, et al. The pivotal role of the complement system in aging and age-related macular degeneration: hypothesis re-visited. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010 Mar;29(2):95–112. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mattapallil MJ, Wawrousek EF, Chan CC, et al. The Rd8 mutation of the Crb1 gene is present in vendor lines of C57BL/6N mice and embryonic stem cells, and confounds ocular induced mutant phenotypes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(6):2921–2927. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen M, Forrester JV, Xu H. Dysregulation in retinal para-inflammation and age-related retinal degeneration in CCL2 or CCR2 deficient mice. PloS one. 2011;6(8):e22818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen M, Hombrebueno JR, Luo C, et al. Age- and light-dependent development of localised retinal atrophy in CCL2(−/−)CX3CR1(GFP/GFP) mice. PloS one. 2013;8(4):e61381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cruz-Guilloty F, Saeed AM, Echegaray JJ, et al. Infiltration of proinflammatory m1 macrophages into the outer retina precedes damage in a mouse model of age-related macular degeneration. Int J Inflam. 2013;2013:503725. doi: 10.1155/2013/503725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollyfield JG, Bonilha VL, Rayborn ME, et al. Oxidative damage-induced inflammation initiates age-related macular degeneration. Nat Med. 2008 Feb;14(2):194–198. doi: 10.1038/nm1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma W, Zhao L, Wong WT. Microglia in the outer retina and their relevance to pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;723:37–42. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0631-0_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fordham JB, Hua J, Morwood SR, et al. Environmental conditioning in the control of macrophage thrombospondin-1 production. Sci Rep. 2012;2:512. doi: 10.1038/srep00512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macaulay R, Akbar AN, Henson SM. The role of the T cell in age-related inflammation. Age (Dordr) 2013 Jun;35(3):563–572. doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9381-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chou JP, Effros RB. T cell replicative senescence in human aging. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19(9):1680–1698. doi: 10.2174/138161213805219711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malaguarnera M, Cristaldi E, Romano G, Malaguarnera L. Autoimmunity in the elderly: Implications for cancer. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012 Oct-Dec;8(4):520–527. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.106527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmitt V, Rink L, Uciechowski P. The Th17/Treg balance is disturbed during aging. Exp Gerontol. 2013 Sep 20;48(12):1379–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao X, Shen D, Patel MM, et al. Macrophage polarization in the maculae of age-related macular degeneration: a pilot study. Path Int. 2011 Sep;61(9):528–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2011.02695.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pawelec G, Akbar A, Caruso C, Solana R, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Wikby A. Human immunosenescence: is it infectious? Immunol Rev. 2005 Jun;205:257–268. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forrester JV. Bowman lecture on the role of inflammation in degenerative disease of the eye. Eye. 2013 Mar;27(3):340–352. doi: 10.1038/eye.2012.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whitcup SM, Sodhi A, Atkinson JP, et al. The role of the immune response in age-related macular degeneration. Int J Inflam. 2013;2013:348092. doi: 10.1155/2013/348092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu B, Wei L, Meyerle C, et al. Complement component C5a promotes expression of IL-22 and IL-17 from human T cells and its implication in age-related macular degeneration. J Trans Med. 2011;9:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei L, Liu B, Tuo J, et al. Hypomethylation of the IL17RC promoter associates with age-related macular degeneration. Cell Rep. 2012 Nov 29;2(5):1151–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morohoshi K, Patel N, Ohbayashi M, et al. Serum autoantibody biomarkers for age-related macular degeneration and possible regulators of neovascularization. Exp Mol Pathol. 2012 Feb;92(1):64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fauci A. Glucocorticoid effects on circulating human mononuclear cells. J Reticuloendothel Soc. 1979;26(suppl):727–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Felinski EA, Cox AE, Phillips BE, Antonetti DA. Glucocorticoids induce transactivation of tight junction genes occludin and claudin-5 in retinal endothelial cells via a novel cis-element. Exp Eye Res. 2008 Jun;86(6):867–878. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geltzer A, Turalba A, Vedula SS. Surgical implantation of steroids with antiangiogenic characteristics for treating neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1:CD005022. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005022.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKinley L, Alcorn JF, Peterson A, et al. TH17 cells mediate steroid-resistant airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. J Immunol. 2008 Sep 15;181(6):4089–4097. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee RW, Creed TJ, Schewitz LP, et al. CD4+CD25(int) T cells in inflammatory diseases refractory to treatment with glucocorticoids. J Immunol. 2007 Dec 1;179(11):7941–7948. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee RW, Schewitz LP, Nicholson LB, Dayan CM, Dick AD. Steroid refractory CD4+ T cells in patients with sight-threatening uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009 Sep;50(9):4273–4278. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nussenblatt RB, Byrnes G, Sen HN, et al. A randomized pilot study of systemic immunosuppression in the treatment of age-related macular degeneration with choroidal neovascularization. Retina. 2010 Nov-Dec;30(10):1579–1587. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181e7978e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaneko H, Dridi S, Tarallo V, et al. DICER1 deficit induces Alu RNA toxicity in age-related macular degeneration. Nature. 2011 Mar 17;471(7338):325–330. doi: 10.1038/nature09830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riley JL, June CH, Blazar BR. Human T regulatory cell therapy: take a billion or so and call me in the morning. Immunity. 2009 May;30(5):656–665. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weiner HL, da Cunha AP, Quintana F, Wu H. Oral tolerance. Immunol Rev. 2011 May;241(1):241–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kau AL, Ahern PP, Griffin NW, Goodman AL, Gordon JI. Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system. Nature. 2011 Jun 16;474(7351):327–336. doi: 10.1038/nature10213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Faria AM, Weiner HL. Oral tolerance. Immunol Rev. 2005 Aug;206:232–259. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nussenblatt RB, Gery I, Weiner HL, et al. Treatment of uveitis by oral administration of retinal antigens: results of a phase I/II randomized masked trial. Amer J Ophthalmol. 1997 May;123(5):583–592. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koffeman EC, Genovese M, Amox D, et al. Epitope-specific immunotherapy of rheumatoid arthritis: clinical responsiveness occurs with immune deviation and relies on the expression of a cluster of molecules associated with T cell tolerance in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot phase II trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Nov;60(11):3207–3216. doi: 10.1002/art.24916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Postlethwaite AE, Wong WK, Clements P, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral type I collagen treatment in patients with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: I. oral type I collagen does not improve skin in all patients, but may improve skin in late-phase disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Jun;58(6):1810–1822. doi: 10.1002/art.23501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kapp K, Maul J, Hostmann A, et al. Modulation of systemic antigen-specific immune responses by oral antigen in humans. Eur J Immunol. 2010 Nov;40(11):3128–3137. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]