Abstract

Purpose

Sorafenib is an inhibitor of VEGFR, PDGFR, and RAF kinases, amongst others. We assessed the association of somatic mutations with clinicopathologic features and clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic melanoma treated on E2603, comparing treatment with carboplatin, paclitaxel +/− sorafenib (CP vs. CPS).

Experimental Design

Pre-treatment tumor samples from 179 unique individuals enrolled on E2603 were analyzed. Genotyping was performed using a custom iPlex panel interrogating 74 mutations in 13 genes. Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher’s exact test, logistic regression, and Cox’s proportional-hazards models. Progression free survival and overall survival were estimated using Kaplan-Meier methods.

Results

BRAF and NRAS mutations were found at frequencies consistent with other metastatic melanoma cohorts. BRAF-mutant melanoma was associated with worse performance status, increased number of disease sites, and younger age at diagnosis; NRAS-mutant melanoma was associated with better performance status, fewer sites of disease, and female gender. BRAF and NRAS mutations were not significantly predictive of response or survival when treated with CPS vs. CP. However, patients with NRAS-mutant melanoma trended towards a worse response and PFS on CP than those with BRAF-mutant or WT/WT melanoma, an association that was reversed for this group on the CPS arm.

Conclusions

This study of somatic mutations in melanoma is the last prospectively collected phase III clinical trial population prior to the era of BRAF targeted therapy. A trend towards improved clinical response in patients with NRAS-mutant melanoma treated with CPS was observed, possibly due to sorafenib’s effect on CRAF.

Keywords: Carboplatin, Metastatic Melanoma, Paclitaxel, Somatic Mutations, Sorafenib

Introduction

Cutaneous melanoma is the most aggressive form of skin cancer. Its incidence and mortality are increasing, with approximately 76,690 new cases and 9,480 deaths related to melanoma projected for 2013.1 In the past few years, based upon improvement in survival, new therapies were approved for the treatment of advanced stage melanoma including the CTLA-4 antagonist - ipilimumab (Yervoy®, Bristol-Myers Squibb, San Francisco, CA), and the targeted BRAF inhibitors, vemurafenib (Zelboraf®, Genentech, San Francisco, CA), dabrafenib (Tafinalar®, GlaxoSmithKline, Philadelphia, PA), and the MEK inhibitor trametinib (Mekinist®, GlaxoSmithKline, Philadelphia, PA).2–7 Prior to the approval of ipilimimab and BRAF inhibitors, no effective, standard treatment existed for advanced melanoma. Patients were treated with dacarbazine or high-dose interleukin-2, which demonstrated limited objective response rates of 10–20%.8,9 Carboplatin and paclitaxel also was used to treat patients with advanced stage melanoma with similar results.3 In the absence of treatment, overall median survival for patients with advanced melanoma is between 9 to 12 months.3,10

Sorafenib (Nexavar®, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Whippany, NJ) is an oral multi-kinase inhibitor which targets angiogenesis, through vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFR); RAF kinases, including BRAF and CRAF; and other receptor tyrosine kinases.11,12 Sorafenib has been demonstrated to be effective in the treatment of renal cell, hepatocellular carcinoma, and most recently differentiated thyroid cancer, mainly through its effects on angiogenesis, and is FDA approved for these indications.13–16 Phase II clinical trials investigated the effect of sorafenib monotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma and demonstrated limited to no response, but a tolerable side effect profile.17,18 A phase I clinical trial investigated the effect of adding sorafenib to carboplatin and paclitaxel in melanoma patients, to increase the effectiveness of chemotherapy, with favorable response rates independent of BRAF mutation status, including one complete response and nine partial responses in patients with melanoma.19 Thus, a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase III trial was initiated by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) to investigate the impact of addition of sorafenib to carboplatin and paclitaxel (ECOG 2603). Although the clinical trial did not demonstrate a difference in overall survival with addition of sorafenib to chemotherapy, it did establish the combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel as a standard of care in treatment of metastatic melanoma, where evidence had been lacking.20

Somatic mutations identified in melanoma tumor tissues have been shown to play an integral role in melanoma pathogenesis. Mutations in BRAF are found in up to 50% of melanomas, with the most common mutation occurring at codon 600 resulting in the BRAFV600 mutation.21–25 NRAS also is mutated in 15–20% of melanomas, with the most common mutation resulting in substitution for the amino acid glutamine (Q) at position 61.26–29 Additional mutations have been identified within both BRAF and NRAS, which occur at lower frequencies. The association of somatic mutations with clinical response to chemotherapy and targeted therapy is not clearly defined, with the exception of targeted inhibition of mutant BRAF.

The current study presents the somatic mutation correlative studies for the large E2603 clinical trial. We utilized the pre-treatment tumor samples from patients enrolled on the E2603 to assess the association of somatic mutations identified in tumor samples with clinicopathologic features and clinical outcomes. E2603 was a randomized, phase III clinical trial of carboplatin/paclitaxel +/− sorafenib. Importantly, patients were included without determination of mutation status in E2603, and this unselected population allowed for the evaluation of the natural history of melanoma, prior to mutant BRAF specific targeted therapy. We also determined whether somatic mutations in patient tumors were associated with progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), alone or in conjunction with known prognostic markers in melanoma.

Materials and Methods

Patients

In the double-blind phase III ECOG 2603 clinical trial, patients were randomized to receive carboplatin/paclitaxel (CP [control arm]) (area under the curve of 6 and 225 mg/m2, respectively, every three weeks) or carboplatin/paclitaxel plus sorafenib (CPS [experimental arm]) (400 mg PO BID days 2–19 of every 21-day cycle).20 In order to be eligible for the study, patients needed to have confirmed melanoma that was unresectable or metastatic; uveal melanomas and patients with brain metastases were excluded. Additional eligibility criteria included measurable disease, age at least 18 years, ECOG performance status (PS) of 0 or 1, and normal baseline laboratory values. Treatment with prior chemotherapy or MAPK pathway targeted therapy were exclusion criteria. All prior therapies, including radiation, needed to be completed at least four weeks prior to trial enrollment.

Patient demographics and tumor characteristics were collected including age at diagnosis, gender, AJCC stage, ECOG PS, Breslow depth, Clark Level, number of sites involved, primary tumor site, ulceration, and LDH level. In addition, the latitudes of individual recruitment sites were identified in order to determine if mutation status was associated with sun exposure; degrees of latitude were stratified in groups of 10 thousand (e.g. 10,000–20,000).

Melanoma Tumor Samples and DNA isolation

Available pre-treatment tumor samples were obtained from patients enrolled on the E2603 clinical trial who gave consent to use their tumor samples under the approval of the Institutional Review Boards of participating centers. The most recent tissue sample was preferred, either diagnostic biopsy or resection; if metastatic tissue was unavailable, primary melanoma samples were permitted. Patients had provided written consent. H&E sections of formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tumor samples were evaluated for tumor quality and content. A single pathologist (DLR) examined each tumor sample to ensure the presence of at least 70% tumor. Tumor samples were macrodissected to over 70% tumor. DNA was isolated from formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tumors, either scraped from slides or extracted from paraffin rolls. After deparafinization, DNA was isolated with sodium thiocyanate, followed by digestion with proteinase K, and precipitated with ammonium acetate. DNA was resuspended in TE and concentrations were determined using picoGreen (Quant-iT™ PicoGreen ® dsDNA Reagent, Invitrogen).

Mutation Analysis/Genotyping

Genotyping was performed using a custom iPlex Sequenom panel interrogating 74 mutations in 13 genes, described in detail in the supplemental methods. Primers and multiplex design are available upon request. Genotyping was done in the Perelman School of Medicine Molecular Profiling Facility. Additional details are provided in Supplemental Methods. Sequencing of BRAF exon 11 mutations were performed on all tumor samples which were wild-type (WT) for BRAF, NRAS, KIT, and GNA11/GNAQ. Primers and PCR conditions are found in supplemental methods.

Statistical Analysis

The Fisher’s exact test was used to compare BRAF and NRAS mutation by patients’ demographic and disease characteristics, and multivariable logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (OR) for BRAF and NRAS mutations for these variables. Fisher’s exact test and multivariable logistic regression were also used to compare the clinical response (complete response (CR) plus partial response (PR)) between treatment arms by BRAF/NRAS mutation status. The distribution of OS and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between groups using log-rank test. Data from the four patients with GNA11/GNAQ mutations were excluded from survival analysis, as these samples most likely originated from metastases from uveal melanomas. Cox’s proportional-hazards models were used to assess the prognostic value of BRAF and NRAS mutation on OS after adjustment for other variables. OS was defined as time from randomization to death from any cause, and patients who were still alive were censored at the date of last known alive. PFS was defined as time from randomization to disease progression or death from any cause (whichever occurred first), and patients who were still alive and had no disease progression were censored at the date of last disease assessment. All p-values were for two-sided test and p<0.05 was considered statistical significance. Due to the exploratory nature of the study, no adjustment was made for multiple comparisons. All analysis was conducted using STATA 11.2.30

Results

Mutation Frequency

From the 823 patients enrolled on the E2603 clinical trial, 620 archival pre-treatment samples were available for analysis. H&E stains of tumor samples were analyzed to determine tumor presence and adequacy for analysis. Of the available samples, 76 (12%) samples had no demonstrable tumor, 241 (39%) samples had insufficient tumor, 22 (4%) samples with H&E slides did not have tumor sample available for processing, and DNA extraction was not performed on one duplicate sample. Two hundred and eighty samples underwent DNA extraction; 243 (87%) of which had adequate DNA for genotyping. Accounting for multiple tumor samples from 31 patients, 179 unique patient samples were analyzed. Eighty one tumor samples were from patients on the control arm (CP) and 98 tumor samples were from patients on the experimental arm (CPS). No significant difference in patient demographic and disease characteristics was found between the 179 patients and the remaining 643 patients not included in the present analysis (data not shown). The overall survival was similar as well (Supplemental Figure 1). Of the 179 patients included in the current analysis, there was no significant difference between two treatment arms regarding known prognostic factors and clinical outcomes (data not shown).

In the 179 analyzable patients, the overall BRAF mutation rate was 45% and NRAS mutation rate was 23% (Table 1). Thirty-three percent of tumors lacked BRAF or NRAS mutations and are termed WT/WT. Mutations in BRAF and NRAS were mutually exclusive, with the exception of one tumor sample which harbored BRAFV600K and NRASA146P mutations. The three observed BRAF exon 11 mutations were p.G464E, p.G469A, and p.G469V. The AKT1E17K mutation was coincident with a BRAFV600E mutation; the AKT3E17K mutation with NRASQ61K mutation. The six CDK4R24 mutations, with different amino acid substitutions, were coincident with BRAFV600E mutations. Four of the five CTNNB1 (beta-catenin) mutations were concurrent with BRAF mutations. One CTNNB1S37F mutation was observed in BRAFV600E mutant tumor, whereas the other sample was WT/WT. Two CTNNB1S45Y mutations were seen in tumors with BRAFV600R mutations, and one, CTNNB1S45F, with BRAFV600E mutation.

Table 1.

Frequency of somatic mutations in tumor samples.

| Gene | Mutation | # mutated | % mutated† |

|---|---|---|---|

| AKT1 | p.E17K | 1 | 0.56 |

|

| |||

| AKT3 | p.E17K | 1 | 0.56 |

|

| |||

| BRAF | exon 11 | 3 | 1.7 |

| p.L597P | 1 | 0.56 | |

| p.V600 all | 78 | 43.82 (36.4–51.4) | |

| p.V600D | 1 | 0.56 | |

| p.V600E | 56 | 31.50 (24.7–38.8) | |

| p.V600K | 16 | 8.99 (5.2–14.2) | |

| p.V600R | 4 | 2.25 | |

| p.K601E | 2 | 1.15 | |

| All* | 80 | 44.70 (37.3–52.3) | |

|

| |||

| CDK4 | p.R24C/G/H | 6 | 3.41 |

|

| |||

| CTNNB1 | p.S37F | 2 | 1.16 |

| p.S45F/Y | 3 | 1.78 | |

|

| |||

| GNA11 | p.Q209L | 1 | 0.71 |

|

| |||

| GNAQ | p.Q209L/P | 3 | 1.83 |

|

| |||

| KIT | p.L576P | 1 | 0.58 |

| p.D816V | 1 | 0.56 | |

| D820Y | 1 | 0.57 | |

|

| |||

| NRAS | p.G13C/D/R/V | 5 | 2.96 |

| p.Q61 all | 35 | 19.77 (14.2–26.4) | |

| p.Q61H | 2 | 1.13 | |

| p.Q61K | 10 | 5.65 (2.7–10.1) | |

| p.Q61L | 4 | 2.26 | |

| p.Q61P | 1 | 0.56 | |

| p.Q61R | 18 | 10.17 (6.1–15.6) | |

| p.A146P | 1 | 0.64 | |

| All** | 41 | 22.90 (17.0–29.8) | |

|

| |||

| WT/WT | 59 | 33 (26.1–40.4) | |

calculated as percentage of patients with data available; exact binomial 95% CI included when numbers sufficient.

BRAF_all includes all BRAF V600 and BRAF K601 mutations and excludes BRAF exon 11 mutations.

NRAS_all includes all NRAS mutations, NRAS G13, NRAS A146, and NRAS Q61.

Association of Mutations with Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics

At the time of initial diagnosis, patients with BRAF mutant melanomas trended towards earlier age of diagnosis (median age cutoff = 58), while those with WT/WT melanomas trended towards older age of diagnosis (Table 2). Patients with BRAF mutant melanomas had a worse ECOG performance status (PS) as compared to those patients with NRAS mutant or WT/WT melanomas (p=0.038). Patients with BRAF mutant melanoma had an increased number of disease sites; 41% of patients with BRAF mutant melanoma had ≥ four sites involved as compared to patients with NRAS mutant (15%) or WT/WT melanomas (22%; P=0.026). In order to assess the effect of sun exposure on mutation status, we used proximity to the equator as a surrogate and stratified recruitment locations by latitude. No mutation was associated with latitude (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation of mutation status with patient demographics and disease characteristics.

| Demographics and disease characteristics | WT/WT | Mutant BRAF | Mutant NRAS | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Age at diagnosis* | Young | 23 | 39.66 | 42 | 57.53 | 19 | 50 | 0.127 |

| Old | 35 | 60.34 | 31 | 42.47 | 19 | 50 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Gender | Male | 40 | 67.80 | 51 | 64.56 | 22 | 55 | 0.416 |

| Female | 19 | 32.20 | 28 | 35.44 | 18 | 45 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| AJCC stage | Unresectable Stage III | 5 | 8.48 | 11 | 13.92 | 7 | 17.50 | 0.747 |

| M1a/M1b | 21 | 35.59 | 25 | 31.65 | 13 | 32.50 | ||

| M1c | 33 | 55.93 | 43 | 54.43 | 20 | 50 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| ECOG Performance status | 0 | 38 | 64.41 | 38 | 48.10 | 28 | 70 | 0.038 |

| 1 | 21 | 35.59 | 41 | 51.90 | 12 | 30 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Number of involved sites | 1 | 13 | 22.03 | 13 | 16.46 | 12 | 30 | 0.026 |

| 2–3 | 33 | 55.93 | 34 | 43.04 | 22 | 55 | ||

| >=4 | 13 | 22.03 | 32 | 40.51 | 6 | 15 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Primary site | Lower limb | 12 | 20.34 | 9 | 11.39 | 9 | 22.50 | 0.107 |

| Trunk | 11 | 18.64 | 29 | 36.71 | 13 | 32.50 | ||

| Other | 36 | 61.02 | 41 | 51.90 | 18 | 45 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Latitude $ | 40–50 | 35 | 59.32 | 44 | 55.70 | 26 | 65 | 0.751 |

| 30–40 | 22 | 37.29 | 29 | 36.71 | 12 | 30 | ||

| 20–30 | 2 | 3.39 | 6 | 7.60 | 2 | 5 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Ulceration | No | 21 | 35.59 | 34 | 43.04 | 18 | 45 | 0.880 |

| Yes | 22 | 37.29 | 25 | 31.65 | 12 | 30 | ||

| Unknown | 16 | 27.12 | 20 | 25.32 | 10 | 25 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| LDH level | Normal | 36 | 62.07 | 41 | 52.56 | 23 | 60.53 | 0.493 |

| Elevated | 22 | 37.93 | 37 | 47.44 | 15 | 39.47 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Breslow depth | Low | 17 | 28.81 | 27 | 34.18 | 18 | 45 | 0.370 |

| High | 21 | 35.59 | 21 | 26.58 | 12 | 30 | ||

| Missing | 21 | 35.59 | 31 | 39.24 | 10 | 25 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Clark level# | SubQ fat | 13 | 36.11 | 8 | 16 | 7 | 25.93 | 0.076 |

| Reticular | 19 | 52.78 | 34 | 68 | 12 | 44.44 | ||

| Other | 4 | 11.11 | 8 | 16 | 8 | 29.63 | ||

P values were from Fisher’s exact test for categorical and binary variables. Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; Sub Q fat, subcutaneous fat; WT, wildtype.

Median age cutoff=58.

Latitudes are presented in quintiles, representing degrees of latitude in 10,000s from the equator (eg 20–30, 20,000–30,000 degrees of latitude).

For Clark level, other includes interface papillary-reticular dermis, extension into papillary dermis, and above basal lamina.

Multivariable logistic regression demonstrated that the BRAF mutation is associated with younger age of diagnosis (OR 2.29, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.10–4.77), ≥4 sites of disease (OR 4.1, 95% CI 1.36–12.38), and disease involvement in the reticular dermis for primary tumors (OR 3.49, 95% CI 1.01–12.10) (Supplemental Table 1). Truncal primary melanomas tended to have a BRAF mutation (OR 3.10, 95% CI 0.95–10.08). Patients were more likely to have a NRAS mutation if they were female (OR 2.79, 95% CI 1.10–7.07) and less likely to have a NRAS mutation with ≥4 sites of disease (OR 0.31, 95% CI 0.08–1.13) (Supplemental Table 1).

We further evaluated disease characteristics of patients whose melanoma had specific BRAFV600 mutations (Table 3), as prior studies have demonstrated different clinicopathologic characteristics.31 Patients with melanomas carrying V600E or V600K mutations demonstrated differences in ages at diagnosis and PS. Patients with BRAFV600E mutants tended to be a younger at diagnosis (p=0.051) and had a significantly worse PS compared to patients whose melanomas carried BRAFV600K (p<0.001).

Table 3.

Correlation of specific BRAFV600 mutations with select patient demographics and disease characteristics.

| Demographics and disease characteristics | WT BRAF | Mutant BRAF | P value | V600E | V600K | P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Age at diagnosis* | Young | 42 | 43.8 | 43 | 58.1 | 0.063 | 34 | 68 | 6 | 40 | 0.051 |

| Old | 54 | 56.3 | 31 | 41.9 | 16 | 32 | 9 | 60 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| ECOG PS | 0 | 66 | 66.7 | 39 | 48.8 | 0.016 | 19 | 34.6 | 13 | 81.3 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 33 | 33.3 | 41 | 51.3 | 36 | 65.5 | 3 | 18.8 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Ulceration | No | 39 | 39.4 | 35 | 43.8 | 0.836 | 24 | 43.6 | 6 | 37.5 | 0.906 |

| Yes | 34 | 34.3 | 25 | 31.3 | 19 | 34.6 | 6 | 37.5 | |||

| Unknown | 26 | 26.3 | 20 | 25 | 12 | 21.8 | 4 | 25 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| LDH level | Normal | 59 | 61.5 | 42 | 53.2 | 0.269 | 29 | 52.7 | 7 | 46.7 | 0.677 |

| Elevated | 37 | 38.5 | 37 | 46.8 | 26 | 47.3 | 8 | 53.3 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Breslow depth | Low | 35 | 35.4 | 28 | 35 | 0.486 | 21 | 38.2 | 3 | 18.8 | 0.196 |

| High | 33 | 33.3 | 21 | 26.3 | 16 | 29.1 | 4 | 25 | |||

| Missing | 31 | 31.3 | 31 | 38.8 | 18 | 32.7 | 9 | 56.3 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Clark level# | Sub Q fat | 20 | 31.8 | 8 | 15.7 | 0.083 | 4 | 10.5 | 3 | 37.5 | 0.095 |

| Reticular | 31 | 49.2 | 35 | 68.6 | 27 | 71.1 | 5 | 62.5 | |||

| Other | 12 | 19.1 | 8 | 15.7 | 7 | 18.4 | 0 | 0 | |||

P values were from Fisher’s exact test for categorical and binary variables. Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; SubQ fat, subcutaneous fat; WT, wildtype.

Median age cutoff=58.

For Clark level, other includes interface papillary-reticular dermis, extension into papillary dermis, and above basal lamina.

Association of Mutations with Clinical Outcomes

In patients with BRAF mutant melanoma, the clinical response rate (CR plus PR) was 15.6% (5/32) and 19.2% (9/47) for control and experimental arms, respectively (P=0.771) (Table 4). In patients with NRAS mutant melanoma, the clinical response rates were 5.6% (1/18) and 22.7% (5/22) for the control and experimental arms, respectively (P=0.197). In WT/WT melanoma, the clinical response rate was similar in the control and experimental arms, 16.7% (5/30) and 20.0% (5/25), respectively (P>0.05). The treatment-by-mutation interaction test was not statistically significant in logistic model for clinical response (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation of response rates with mutation status and study arm.

| Mutated gene | Control Arm$ | Experimental Arm$ | Odds ratio& (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-response | Response | Non-response | Response | ||

| BRAF | 84.4 | 15.6 | 80.9 | 19.2 | 1.99 (0.48–8.30) |

| V600E | 81.0 | 19.0 | 85.3 | 14.7 | 0.73 (0.17–3.11) |

| V600K | 83.3 | 16.7 | 70.0 | 30.0 | 2.14 (0.17–27.10) |

| NRAS | 94.4 | 5.6 | 77.3 | 22.7 | 4.26 (0.36–49.74) |

| WT/WT | 83.3 | 16.7 | 80.0 | 20.0 | 1.28 (0.28–5.91) |

Response - complete response (CR) + partial response (PR). Non-response = stable disease (SD) + progression (PD) + un-evaluable. Control arm: carboplatin/paclitaxel; Experiment arm: carboplatin/paclitaxel + sorafenib.

p values >0.05 from Fisher’s exact test for all comparisons of response rate between two treatment arms.

Odds ratio of experimental arm/control arm for tumor response, calculated using multivariable logistic model with treatment-by-mutation interaction term, adjusting for other demographic and disease characteristics. P>0.05 for the treatment-by-mutation interaction tests.

WT, wildtype, CI: confidence interval.

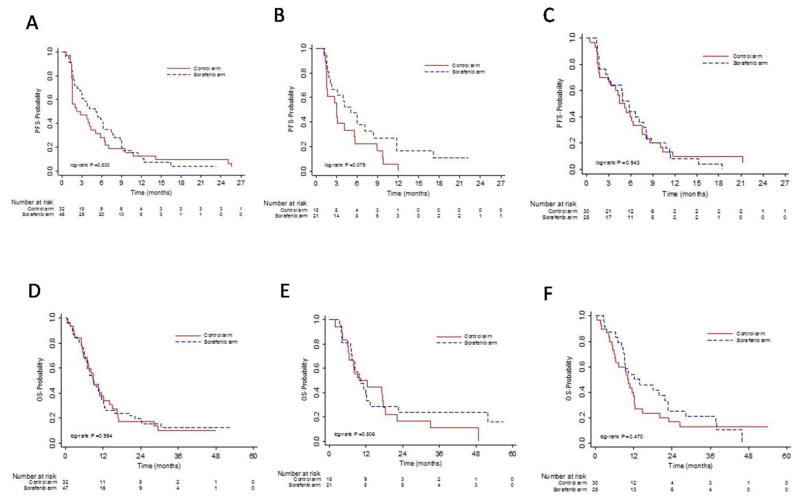

In patients with BRAF mutant melanoma, the median PFS was 2.2 and 5.0 months for the control and experimental arms, respectively, and median OS was 8.8 and 8.9 months for control and experimental arm, respectively (Figure 1A, D). In patients with NRAS mutant melanoma, the median PFS was 3.0 and 5.1 months for control and experimental arms, respectively, and the median OS was 9.8 and 10.3 months for control and experimental arms, respectively (Figure 1B, E). In patients with WT/WT melanoma, the median PFS was 4.5 and 5.8 months for control and experimental arms, respectively, and median OS was 10.0 and 12.1 months for the control and experimental arms, respectively (Figure 1C, F).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) based on mutation status. (A), (B), and (C) Kaplan-Meier estimates for PFS for patients with BRAF mutations, NRAS mutations, and WT/WT, respectively, for control and experimental arms. (D), (E), and (F) Kaplan -Meier estimates for OS for patients with BRAF mutations, NRAS mutations, and WT/WT, respectively, for control and experimental arms. Control arm, carboplatin/paclitaxel; experimental arm, carboplatin/paclitaxel/sorafenib.

The results of this study demonstrated no difference between the two treatment arms in OS and PFS and no association with treatment outcome and BRAF and NRAS mutations. Consequently, the treatment arms were collapsed, as called for in our prospectively defined analysis plan, and we examined the relationship of BRAF and NRAS mutations with OS. Multivariable Cox regression was used to assess the prognostic value of BRAF and NRAS mutations on OS after adjustment for additional prognostic variables known to influence melanoma prognosis (Table 5). Our results demonstrate that BRAF and NRAS mutations are not prognostic factors for OS in E2603 patients. Worse PS (HR 2.22, 95% CI 1.46–3.37, p<0.001) and elevated LDH (HR 2.16, 95% CI 1.42–3.28, p<0.001) predicted for worse survival in patients. The primary site of melanoma also was a significant prognostic marker in this study. Patients with truncal primary melanomas, when compared to lower limb melanomas, had worse survival (HR 2.41, 95% CI 1.29–4.49, p=0.006), as did patients with melanomas at sites other than lower limb and trunk (HR 1.99, 95% CI 1.13–3.52, p=0.017). When years since diagnosis was analyzed as a continuous variable, increased time was associated with a decreased survival (HR 0.94, 95% CI 0.89–1, p=0.039).

Table 5.

Cox regression for OS

| Demographic and disease characteristics | Levels | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRAF/NRAS | Mutant BRAF v WT/WT | 1.24 | 0.78 | 1.96 | 0.361 |

| Mutant NRAS v WT/WT | 0.91 | 0.55 | 1.51 | 0.716 | |

| Treatment | CPS v CP | 0.74 | 0.50 | 1.08 | 0.119 |

| Age at diagnosis | ≥58 v <58 | 1.11 | 0.74 | 1.65 | 0.611 |

| Years since diagnosis | Continuous | 0.94 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 0.039 |

| Gender | Female v Male | 1.14 | 0.73 | 1.76 | 0.565 |

| AJCC stage | M1a/M1b v Unresectable stage III | 0.64 | 0.34 | 1.20 | 0.163 |

| M1c v Unresectable stage III | 0.76 | 0.41 | 1.39 | 0.373 | |

| ECOG performance status | 1 v 0 | 2.22 | 1.46 | 3.37 | ≤0.001 |

| Prior therapy | IFN/IL-2/GM-CSF v None | 0.94 | 0.65 | 1.37 | 0.754 |

| One investigational therapy v None | 3.14 | 0.95 | 10.43 | 0.062 | |

| Number of involved sites | 2–3 v 1 | 1.31 | 0.80 | 2.14 | 0.283 |

| ≥4 v 1 | 1.02 | 0.55 | 1.88 | 0.957 | |

| Ulceration | Yes v No | 1.14 | 0.72 | 1.80 | 0.571 |

| Unknown v No | 0.98 | 0.53 | 1.82 | 0.960 | |

| Clark level | Reticular v SubQ fat | 0.42 | 0.22 | 0.77 | 0.006 |

| Other v SubQ fat | 0.65 | 0.29 | 1.49 | 0.311 | |

| Unknown v SubQ fat | 0.82 | 0.39 | 1.73 | 0.600 | |

| LDH | Elevated v Normal | 2.16 | 1.42 | 3.28 | ≤0.001 |

| Breslow depth | High v Low | 0.95 | 0.55 | 1.63 | 0.852 |

| Missing v Low | 0.85 | 0.43 | 1.70 | 0.648 | |

| Primary site | Trunk v Lower limb | 2.41 | 1.29 | 4.49 | 0.006 |

| Other v Lower limb | 1.99 | 1.13 | 3.52 | 0.017 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; Sub Q fat, subcutaneous fat, LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; WT, wildtype, CI: confidence interval.

Median age cutoff=58.

For Clark level, other includes interface papillary-reticular dermis, extension into papillary dermis, and above basal lamina.

Discussion

We investigated the correlation between somatic mutations and clinical outcome in melanoma patients treated on the E2603 randomized phase III clinical trial. Notably, patients were randomized to treatment arms without prior knowledge of mutation status. Tumor samples from patients on the E2603 clinical trial also provided a large sample population in which to study the natural history of melanoma, prior to the era of BRAF targeted therapy. We identified mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and WT/WT melanomas at frequencies consistent with published data 23,31,32. We also identified less frequent mutations in BRAF (i.e. BRAFK601E and exon 11 mutations BRAFG464E, BRAFG469A, and BRAFG469V) and NRAS (i.e. G13R, G13V, G13C, and G13D), as well as low frequency mutations in other genes integral to melanoma pathogenesis. We identified mutations in GNA11/GNAQ in four tumor samples. These tumors most likely represent metastatic uveal melanomas, as patients with melanoma of unknown primary were permitted on the study, which were excluded in data analysis.

We evaluated the association of mutations with patient demographics and disease characteristics combining data from control and experimental arms, as no differences were identified between the two arms. BRAF mutations were associated with worse PS and increased number of sites of disease as compared to NRAS mutations and WT/WT melanomas. Younger age at diagnosis emerged as significant in logistic regression analysis. Truncal primary site of melanoma was marginally associated with higher proportion of BRAF mutation in bivariate analysis and significantly so in multivariable analysis. These results are consistent with observations that have been previously reported.23,31,33–35

Patients with NRAS mutant melanoma had better PS (PS=0) and fewer sites of disease involvement (less than four) than patients with BRAF mutant melanoma. The increased number of sites of disease involvement associated with BRAF mutation has not been previously reported in the literature and is a new observation in this set of tumor samples. Also, the presence of a NRAS mutation was associated with female gender in multivariable analysis. Previous studies have not observed an association with female gender, but have observed associations of NRAS mutations with increased Breslow depth and older age at diagnosis 25,26,32,33,36.

Interestingly, patients with BRAFV600K mutant melanoma had significantly better PS than those with BRAFV600E mutant melanoma. Moreover, patients with BRAFV600K mutant melanoma tended to have an older age at the time of diagnosis than those with BRAFV600E mutant melanoma, which although not statistically significant, is consistent with prior observations.31 This finding may be due to the double nucleotide change that is observed with BRAFV600K mutation which could be associated with sun exposure and increased at older ages.

Overall, BRAF and NRAS mutations were not predictive of tumor response to sorafenib in the study. The number of samples with sufficient DNA significantly limited our power to detect potentially meaningful differences in outcome. However, it is important to note that it appears that there was a trend towards a difference in clinical response in patients with NRAS mutations. Patients with NRAS mutant melanoma demonstrated a response rate similar to BRAF mutant and WT/WT melanomas when sorafenib was added to chemotherapy (5.6% vs. 22.7% for NRAS; 15.6% vs. 19.2% for BRAF; and 16.7% vs. 20% for WT/WT), a result that remains potentially important in light of the current lack of targeted therapy options for these patients. Additionally, patients with NRAS mutant melanoma experienced increased PFS with the addition of sorafenib to chemotherapy, with PFS similar to those observed with BRAF mutant or WT/WT melanomas. Similar results were observed in NRAS mutant melanomas in the phase I trial of carboplatin, paclitaxel, and sorafenib19; an increased response rate was observed in patients with NRAS mutant melanoma. Our study was under powered to draw definitive conclusions regarding outcomes in the NRAS mutant subset. Sorafenib has activity against multiple kinases, including CRAF 12,37,38, and we hypothesize that improved responses observed in patients with NRAS mutations are due to CRAF inhibition39–41, although effects on angiogenesis cannot be ruled out. However, in light of the lack of targeted therapies for NRAS mutant melanoma, sorafenib, or other MAPK pathway inhibitors, might warrant investigation in this subset. Of note, there are ongoing clinical trials investigating the effect of MEK inhibitors, either alone or in combination with CDK4/6 or PI3K/mTOR inhibitors, in patients with NRAS mutations (www.clinicaltrials.gov), for which results are eagerly anticipated.

Cox regression for OS demonstrated that neither BRAF nor NRAS mutation is a prognostic biomarker for OS in melanoma patients on ECOG 2603. Previous findings have demonstrated conflicting reports regarding the prognostic value of NRAS and BRAF mutations23,32,33,36,42. No difference in OS was detected in 223 primary melanomas when stratified based on mutational status, specifically BRAF mutant, NRAS mutant, and WT melanomas36. Another study demonstrated no difference in time to development of metastatic disease in melanoma patients with BRAF mutations versus BRAF wildtype23; NRAS mutations were not evaluated in this study. In a panel of 249 primary invasive melanomas, the presence of a NRAS mutation was found to be an independent predictor of worse melanoma specific survival33. However, in this study, only 14% (36/249) of the tumor samples had a NRAS mutation, compared to 45% (112/249) BRAFV600E and 40% (101/249) WT. Mutation status was not associated with a survival difference once patients had developed metastatic disease33. In a larger study analyzing 677 melanoma tumor samples, patients with NRAS mutations (20.1%, 136/677) had a shorter median OS from time of metastatic diagnosis compared to patients with WT melanomas32. Moreover, NRAS mutations were independently associated with decreased survival in multivariate analysis32. It has not been clear if the differential survival in patients with NRAS mutant melanoma is due to intrinsic differences in the biology of NRAS, BRAF mutant and WT/WT melanomas or because NRAS mutant melanomas respond more poorly to the therapies used. We did not observe a difference in survival based on melanoma mutation status, but the limited size of our sample set may have limited our power to detect a difference. However, it is important to note that we observed worse response rates with chemotherapy alone in patients with NRAS mutant melanoma than in those with BRAF mutant and WT/WT melanomas. These data suggest that the reason for the decreased survival in patients with NRAS mutant melanoma observed in prior studies may be due to a decreased response to chemotherapy, rather than other differences in biology of NRAS mutant melanomas, particularly notable in this sample set in which patients with NRAS mutant melanoma had a better PS and fewer sites of disease.

Our study was limited in the number of samples available for analysis for each treatment subgroup. Although 823 patients were enrolled on this clinical trial, biopsy samples were not a requirement for trial entry and were obtained from patients who consented for use of their available tumor samples. Thus, only 179 samples were successfully genotyped and included in the current analysis. However, the individuals from whom samples were genotyped were not significantly different compared to all of the patients on E2603. The issue of insufficient tissue highlights the importance of prospective tissue collection in future clinical trials to empower predictive biomarker investigations.

In conclusion, we evaluated tumor samples from patients with advanced melanoma (unresectable Stage III or Stage IV) prospectively recruited from a wide range of institutions, representing a varied collection of melanoma tumor samples. We have demonstrated associations between mutation status and clinicopathologic features and patient and disease characteristics. Moreover, while our data is underpowered for the analysis of genetically-defined subsets, the observed associations suggest that targeting the MAPK pathway, with sorafenib in this study, may have an effect on clinical outcome in patients with certain mutations, particularly NRAS mutant melanoma. Ongoing clinical trials also seek to target the MAPK pathway to more effectively treat NRAS mutant melanoma.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

We present the somatic mutation correlative studies for E2603, a randomized ECOG clinical phase III trial investigating the benefit of sorafenib added to carboplatin and paclitaxel in advanced stage melanoma patients. Though this trial failed to demonstrate a significant contribution of sorafenib, the observed effects of carboplatin/paclitaxel have resulted in this regimen being considered a standard treatment for metastatic melanoma. Our results suggest patients with NRAS mutant melanoma do worse with chemotherapy alone, possibly explaining the poor prognosis observed in these patients in other studies. However, there was a trend towards improvement in clinical response and PFS in these patients with the addition of sorafenib, equivalent to patients with BRAF mutant and WT/WT melanoma. This finding suggests that non-BRAF selective MAPK inhibitors may have a role in targeted therapy for this population, an important insight given the lack of molecularly targeted therapeutic options for NRAS mutant melanoma.

Acknowledgments

Research support:

This study was coordinated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (Robert L. Comis, M.D., Chair) and supported in part by Public Health Service Grants CA23318, CA66636, CA21115, CA15488, CA14958, CA39229 and from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services. Its content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute. This research was funded in part by a NCI Cancer Center Research Training Program Grant T32 CA009615 (PI: Dr. John Maris) (MAW), NIH Grant R01-CA115756 (HMK), and NIH GRANT RO1-CA118871 (KLN, KTF).

Footnotes

Presented in part at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, March-April 2012 and the Society for Melanoma Research Annual Meeting, Hollywood, CA, November 2012.

Authors’ disclosures of potential conflict of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article. The authors’ declare no conflict of interest at this time.

References

- 1.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Neyman N, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2010. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2013. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/, based on November 2012 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falchook GS, Lewis KD, Infante JR, Gordon MS, Vogelzang NJ, DeMarini DJ, et al. Activity of the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib in patients with advanced melanoma: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:782–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70269-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, Nathan P, Garbe C, Milhem M, et al. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:107–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, Jouary T, Gutzmer R, Milward M, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:358–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60868-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim KB, Kefford R, Pavlick AC, Infante JR, Ribas A, Sosman JA, et al. Phase II study of the MEK1/MEK2 inhibitor Trametinib in patients with metastatic BRAF-mutant cutaneous melanoma previously treated with or without a BRAF inhibitor. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:482–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.5966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atkins MB, Kunkel L, Sznol M, Rosenberg SA. High-dose recombinant interleukin-2 therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma: long-term survival update. Cancer J Sci Am. 2000;6 (Suppl 1):S11–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Comis RL. DTIC (NSC-45388) in malignant melanoma: a perspective. Cancer Treat Rep. 1976;60:165–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sosman JA, Kim KB, Schuchter L, Gonzalez R, Pavlick AC, Weber JS, et al. Survival in BRAF V600-mutant advanced melanoma treated with vemurafenib. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:707–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qi RQ, He L, Zheng S, Hong Y, Ma L, Zhang S, et al. BRAF exon 15 T1799A mutation is common in melanocytic nevi, but less prevalent in cutaneous malignant melanoma, in Chinese Han. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1129–38. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilhelm SM, Adnane L, Newell P, Villanueva A, Llovet JM, Lynch M. Preclinical overview of sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor that targets both Raf and VEGF and PDGF receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3129–40. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, Szczylik C, Oudard C, Siebels M, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:125–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strumberg D, Clark JW, Awada A, Moore MJ, Richly H, Hendlisz A, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and preliminary antitumor activity of sorafenib: a review of four phase I trials in patients with advanced refractory solid tumors. Oncologist. 2007;12:426–37. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-4-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strumberg D, Richly H, Hilger RA, Schleucher N, Korfee S, Tewew M, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of the Novel Raf kinase and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor BAY 43-9006 in patients with advanced refractory solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:965–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brose MS, Nutting C, Jarzab B, Elisei R, Siena S, Bastholt L, et al. Sorafenib in locally advanced or metastatic patients with radioactive iodine-refreactory differentiated thyroid cancer: The phase III DECISION trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31 doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3865.2014.01.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisen T, Ahmad T, Flaherty KT, Gore M, Kaye S, Marais R, et al. Sorafenib in advanced melanoma: a Phase II randomised discontinuation trial analysis. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:581–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ott PA, Hamilton A, Min C, Safarzadeh-Amiri S, Goldberg L, Yoon J, et al. A phase II trial of sorafenib in metastatic melanoma with tissue correlates. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flaherty KT, Schiller J, Schuchter LM, Liu G, Tuveson DA, Redlinger M, et al. A phase I trial of the oral, multikinase inhibitor sorafenib in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4836–42. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flaherty KT, Lee SJ, Zhao F, Schuchter LM, Flaherty L, Kefford R, et al. Phase III trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel with or without sorafenib in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:373–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chin L, Garraway LA, Fisher DE. Malignant melanoma: genetics and therapeutics in the genomic era. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2149–82. doi: 10.1101/gad.1437206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephans P, Edkins S, Clegg S, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–54. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long GV, Menzies AM, Nagrial AM, Haydu LE, Hamilton AL, Mann GJ, et al. Prognostic and clinicopathologic associations of oncogenic BRAF in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1239–46. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller AJ, Mihm MC., Jr Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:51–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Omholt K, Platz A, Kanter L, Ringborg U, Hansson J. NRAS and BRAF mutations arise early during melanoma pathogenesis and are preserved throughout tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:6483–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edlundh-Rose E, Egyhazi S, Omholt K, Mansson-Brahme E, Platz A, Hansson J, et al. NRAS and BRAF mutations in melanoma tumours in relation to clinical characteristics: a study based on mutation screening by pyrosequencing. Melanoma Res. 2006;16:471–8. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000232300.22032.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goel VK, Lazar AJ, Warneke CL, Reston MS, Haluska FG. Examination of mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and PTEN in primary cutaneous melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:154–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van’t Veer LJ, Burgering BM, Versteeg R, Boot AJ, Ruiter DJ, Osanto S, et al. N-ras mutations in human cutaneous melanoma from sun-exposed body sites. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:3114–6. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.7.3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russo AE, Torrisi E, Bevelacqua Y, Perrotta R, Libra M, McCubrey JA, et al. Melanoma: molecular pathogenesis and emerging target therapies (Review) Int J Oncol. 2009;34:1481–9. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Resease 11 CSTSL. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menzies AM, Haydu LE, Visintin L, Carlino MS, Howe JR, Thompson JF, et al. Distinguishing clinicopathologic features of patients with V600E and V600K BRAF-mutant metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3242–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jakob JA, Bassett RL, Jr, Ng CS, Curry JL, Joseph RW, Alvarado GC, et al. NRAS mutation status is an independent prognostic factor in metastatic melanoma. Cancer. 2012;118:4014–23. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Devitt B, Liu W, Salemi R, Wolfe R, Kelly J, Tzen CY, et al. Clinical outcome and pathological features associated with NRAS mutation in cutaneous melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011;24:666–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2011.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viros A, Fridlyand J, Bauer J, Lasithiotakis K, Garbe C, Pinkel D, et al. Improving melanoma classification by integrating genetic and morphologic features. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curtin JA, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T, Patel HN, Busam KJ, Kutzner H, et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2135–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellerhorst JA, Greene VR, Ekmekcioglu S, Warneke CL, Johnson MM, Cooke CP, et al. Clinical correlates of NRAS and BRAF mutations in primary human melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:229–35. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adnane L, Trail PA, Taylor I, Wilhelm SM. Sorafenib (BAY 43-9006, Nexavar), a dual-action inhibitor that targets RAF/MEK/ERK pathway in tumor cells and tyrosine kinases VEGFR/PDGFR in tumor vasculature. Methods Enzymol. 2006;407:597–612. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)07047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang YS, Adnane J, Trail PA, Levy J, Henderson A, Xue D, et al. Sorafenib (BAY 43-9006) inhibits tumor growth and vascularization and induces tumor apoptosis and hypoxia in RCC xenograft models. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;59:561–74. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0393-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dumaz N. Mechanism of RAF isoform switching induced by oncogenic RAS in melanoma. Small GTPases. 2011;2:289–292. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.2.5.17814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaiswal BS, Janakiraman V, Kljavin NM, Eastham-Anderson J, Cupp JE, Liang Y, et al. Combined targeting of BRAF and CRAF or BRAF and PI3K effector pathways is required for efficacy in NRAS mutant tumors. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5717. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sullivan RJ, Flaherty K. MAP kinase signaling and inhibition in melanoma. Oncogene. 2013;32:2373–9. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ekedahl H, Cirenajwis H, Harbst K, Carneiro A, Nielson K, Olsson H, et al. The clinical significance of BRAF and NRAS mutations in a clinic-based metastatic melanoma cohort. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1049–55. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.