Abstract

Lung cancer commonly displays a number of recurrent genetic abnormalities and about 30% of lung adenocarcinomas carry activating mutations in the K-ras gene; often concomitantly with inactivation of tumor suppressor genes p16INK4A and p14ARF of the CDKN2A/B locus. However, little is known regarding the function of p15INK4B translated from the same locus. To determine the frequency of CDKN2A/B loss in human mutant K-ras lung cancer, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database was interrogated. Two-hit inactivation of CDKN2A and CDKN2B occurs frequently in mutant K-ras lung adenocarcinoma patients. Moreover, p15INK4B loss occurs in the presence of biallelic inactivation of p16INK4A and p14ARF suggesting that p15INK4B loss confers a selective advantage to mutant K-ras lung cancers that are p16INK4A and p14ARF deficient. To determine the significance of CDKN2A/B loss in vivo, genetically engineered lung cancer mouse models that express mutant K-ras in the respiratory epithelium were utilized. Importantly, complete loss of CDKN2A/B strikingly accelerated mutant K-ras driven lung tumorigenesis, leading to loss of differentiation, increased metastatic disease and decreased overall survival. Primary mutant K-ras lung epithelial cells lacking CDKN2A/B had increased clonogenic potential. Furthermore, comparative analysis of mutant K-ras;CDKN2A null with K-ras;CDKN2A/B null mice and experiments with mutant K-ras;CDKN2A/B deficient human lung cancer cells indicated that p15INK4B is a critical tumor suppressor. Thus, the loss of CDKN2A/B is of biological significance in mutant K-ras lung tumorigenesis by fostering cellular proliferation, cancer cell differentiation and metastatic behavior.

Implications

Implications: These findings indicate that mutant K-ras;CDKN2A/B null mice provide a platform for accurately modeling aggressive lung adenocarcinoma and testing therapeutic modalities.

Keywords: CDKN2AB, mutant KRAS, lung cancer, mouse lung cancer models

Introduction

Lung adenocarcinoma, a leading source of cancer related mortality world-wide (1), harbors recurrent genomic abnormalities that provide a framework for the selection of targeted therapeutic agents (2-4). For these reasons, intense research efforts are under way to characterize the biological and therapeutic significance of recurrent genomic abnormalities in NSCLC. Activating mutations of KRAS occur in ∼30% of lung adenocarcinomas. KRAS is a small GTPase that regulates several oncogenic networks (5). Mutant KRAS plays a causative role in lung tumorigenesis, however it is not sufficient for the induction of high-grade lung adenocarcinomas in the absence of co-operating mutations that often involve the CDKN2AB locus (6-9).

The CDKN2AB locus encodes for several tumor suppressors. CDKN2A contains p16INK4A and p14ARF (p19Arf in mice), while CDKN2B contains p15INK4B. Both, p16INK4A and p15INK4B promote G1 cell cycle arrest by inhibiting the CDK4/CDK6-retinoblastoma family of tumor suppressors, while p14ARF upregulates TP53 by inactivating its negative regulator MDM2 (10, 11). Both p16INK4A and p15INK4B are highly similar and appear to have originated from gene duplication (12-14), while p14ARF gene expression is initiated from an exon intercalated between p16INK4A and p15INK4B and an alternative reading frame of exon 2 and 3 of p16INK4A (14, 15) (Figure 1A). Several studies established that p16INK4A and p14ARF are bona fide tumor suppressors in vivo including in mutant KRAS lung adenocarcinomas (6, 9, 15-17).

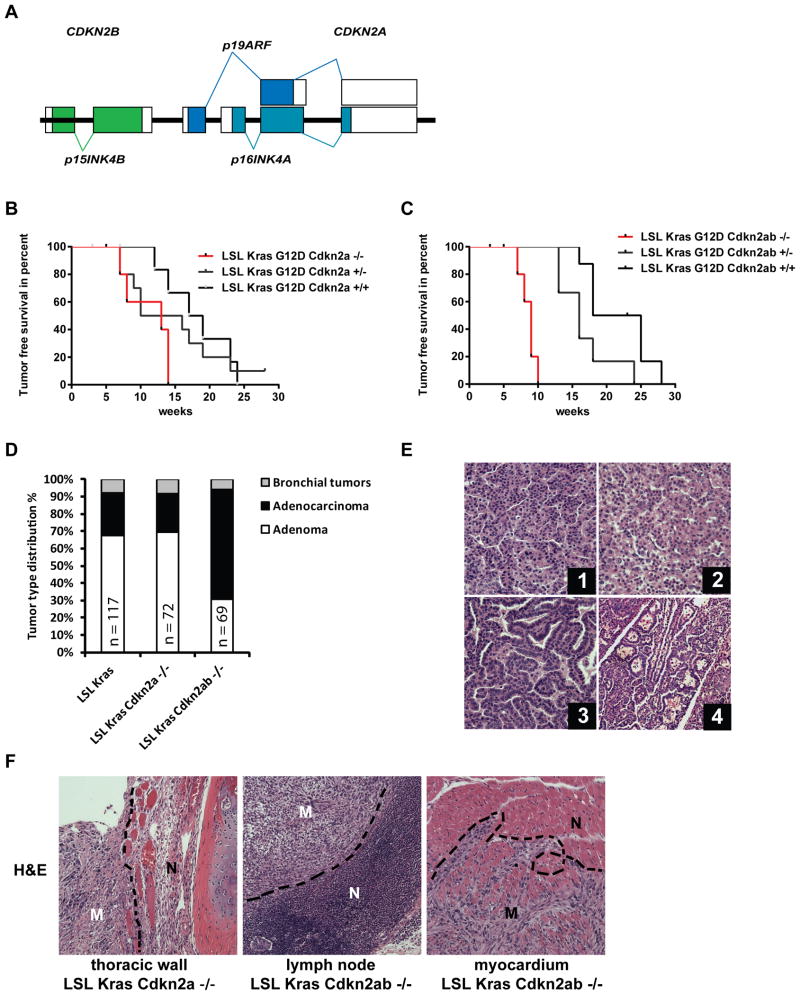

Figure 1. Loss of Cdkn2ab results in aggressive lung cancer in an oncogenic Kras conditional mouse.

(A) Schematic of the Cdkn2ab locus in the mouse (not to scale). (B) Kaplan Meier survival curve of mice with the indicated genotypes (n=8, p=0.024, Log-Rank, Mantel-Cox, wild type versus Cdkn2a null). (C) Kaplan Meier Survival curve of mice with the indicated genotypes. Note that while LSL-Kras;Cdkn2ab+/+ mice have a half-life of 21.5 weeks (n=8), LSL-Kras;Cdkn2ab-/- mice (n=7) have their half-life reduced to 9 weeks (p<0.0001, Log-Rank, Mantel-Cox). (D) Histogram of tumor type distribution of conditional mice with the indicated genotypes. Numbers of tumors counted are indicated. (E) Representative images of lung cancers stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). (1) Lung adenoma of LSL-Kras and (2) of LSL-Kras;Cdkn2a-/- mice. (3) Adenocarcinoma of LSL-Kras;Cdkn2ab-/- mice and (4) bronchial tumor of LSL-Kras;Cdkn2ab-/-, magnification 200 fold. (F) Metastases in the indicated genotypes and anatomic location. M: metastatic tissue, N: normal tissue. H&E staining, magnification 100 fold.

Despite convincing biochemical evidence that p15INK4B is part of the TGF beta signaling pathway, much less is known regarding its tumor suppressor function in vivo (18). For example, p15INK4B is rarely mutated independently of the other CDKN2AB genes (14). Furthermore, in the absence of other mutations, p15INK4B null mice have only a mild tumor predisposition (19). However, the group of Anton Berns demonstrated that Cdkn2ab null mice are tumor-prone and develop an expanded tumor spectrum as compared to Cdkn2a null mice (20). This study led to the conclusion that p15INK4B provides a tumor suppressive function that is critical in the absence of p16INK4A and p19ARF (20). It is unknown whether p15INK4B has a tumor suppressive role in other tumor models or whether its status influences tumorigenesis driven by activating mutations of proto-oncogenes commonly occurring in human cancer. For instance, even though p15INK4B loss has been reported to occur in lung adenocarcinoma, its biological significance has yet to be established in this context (2, 21, 22).

In this manuscript, we study the significance of Cdkn2ab deficiency in the biology of mutant Kras lung adenocarcinoma with two genetically engineered mouse models that express mutant KRAS in the respiratory epithelium, and human lung cancer cell lines. Furthermore, we determined the mutation frequency and pattern of the CDKN2A and CDKN2B loci by analyzing The Tumor Cancer Genome Atlas database. Our data indicate that p15INK4B provides a tumor suppressive function in mutant KRAS lung tumorigenesis.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and lentiviral particle production

The cDNA of murine Cdkn2b (clone ID 3495097) was obtained from Open Biosystems (Thermo) and cloned into pLVX-tight-puro (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA). Recombinant lentiviral particles were generated in 293T cells according to manufactures procedures.

Mouse models and tumor burden assessment

Tet-op-Kras;CCSP-rtTA were obtained from H. E. Varmus (6), HIST1H2BJ-GFP mice were from the Jackson Laboratory (23), Ink4ab-/- mice (hereafter named Cdkn2ab-/-) were provided by Dr. Anton Berns (The Netherlands Cancer Institute Amsterdam, Netherlands), LSL-KrasG12D mice from the NCI mouse repository (24) and Ink4a/Arf flox/flox mice from the Jackson Laboratory (25). Mice were maintained in a mixed background (FVB/N/CD-1). Experiments were performed with F3 generation progeny or later progenies, and comparisons were made with littermates. We obtained lung specific KRAS expression at 4 weeks of age either by feeding mice with doxy implemented food pellets (Harlan Laboratories) or by intratracheal administration of Adenovirus-Cre at 8 weeks of age (University of Iowa, Gene transfer Vector Core) (6, 26). We administered doxycycline at 4 weeks of age to attempt to develop lung tumors prior to the development of tumors involving other organs, a common occurrence in Cdkn2ab null mice. All animal studies were completed according to the policies of the UT Southwestern Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. We used digital quantification of the area occupied by tumors to the area of total lung using the NIH ImageJ (v1.42q) software.

Primary cultures and colony formation assays

Single cell suspensions of primary respiratory cells were sorted with a MoFlo cell sorter to select and plate GFP fluorescent cells on either irradiated or mitomycin C treated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs).

Cell lines

Human NSCLC cell lines H460 and A549 were from the Hamon Center cell line repository (UT Southwestern Medical Center).

Quantitative real-time PCR

We extracted RNA using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and generated cDNA using iScript™ cDNA kit (Biorad). For quantitative real time PCR, we used iTaq SYBR green supermix with ROX (Biorad).

Western blotting

We used the following antibodies: anti-PARP (Cell Signaling), anti-HSP90 (BD Bioscience), anti-p15 (Sigma) and anti-phospho-H3 (Millipore).

Immunohistochemistry

We used the following antibodies: GFP (Chemicon), phospho-S6 ribosomal protein, HMG2A and phospho-Erk (Cell Signaling), ALDH1A1 (Abcam), phospho-H3 (Millipore), NKX2-1 (Santa Cruz), SP-C (Chemicon) and CCSP (Santa Cruz). An HMG2A staining scoring system was used as follows: tumors were considered negative if no stain was visible, positive in few cells, positive in clusters of cells and positive if >50% of tumor cells scored HMG2a positive.

Analyses of the TCGA database

Information regarding mutation, segmented copy number, methylation, and clinical data of primary lung adenocarcinomas were obtained from TCGA data portal (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga) on June 8th, 2013. Only non-silent mutations were considered as described (27). Kaplan-Meier was used to estimate the survival curves and comparisons were performed using the log-rank test using SPSS Statistics 17.0. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test was used to compare the pathologic stage among groups.

Copy number and microarray analysis of lung cancer cell lines

Most of the KRAS and CDKN2A mutations data were obtained from the COSMIC database (Sanger Institute, UK), the literature or from our unpublished whole-exome sequencing data (28). mRNA expression microarrays were performed by us with Illumina HumanWG-6 V3 as previously described (29). They were deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under the accession GSE32036. Whole-genome SNP profiling was done as previously described (30).

Results

Cdkn2ab deficiency accelerates mutant KRAS lung tumorigenesis in mice

To characterize the effect of deficiency of genes encoded by Cdkn2ab on lung tumorigenesis (Fig. 1A), we generated compound mutant mice expressing mutant KRAS in the respiratory epithelium. We crossed LSL-KrasG12D mice (LSL-Kras mice), which encode a latent mutant Kras gene, with mice harboring conditional alleles of Cdkn2a or Cdk2ab (20, 24, 25). We achieved lung specific tumor development by intratracheal delivery of adenovirus encoding for the Cre recombinase.

The overall median survival of LSL-Kras;Cdkn2a-/- was significantly decreased as compared to their littermates with a wild type Cdkn2a locus, while LSL-Kras;Cdkn2a+/- had a trend toward an intermediate survival between Cdkn2a wild type and null genotypes (Figure 1B). The survival of LSL-Kras;Cdkn2ab-/- mice was significantly decreased as compared to LSL-Kras, LSL-Kras;Cdkn2ab+/- or LSL-Kras;Cdkn2a-/- mice (Figure 1C). These findings demonstrate that complete loss of Cdkn2ab significantly promotes mutant KRAS lung tumorigenesis.

Mutant KRAS induces high-grade and metastatic lung adenocarcinomas in Cdkn2ab null mice

At the time of death, the majority of lung parenchyma was occupied by lung tumors in every genotype (Supplemental Figure S1A-C). This finding suggests that death is caused by respiratory compromise.

We determined genotype-specific histological features: lungs of LSL-Kras and LSL-Kras;Cdkn2a-/- mice contained predominantly lung adenomas (Figure 1D and E, panel 1 and 2) and occasional carcinomas with nuclear atypia (not shown). In contrast, Cdkn2ab null mice carried primarily high-grade lung adenocarcinomas consisting of atypical nuclei arranged in papillary structures (Figure 1E, panel 3). Moreover, we detected tumors arising from the bronchial epithelia in all three genotypes (Figure 1D and E, panel 4).

We observed that 44% of LSL-Kras;Cdkn2a-/- mice carried metastatic lesions in mediastinal lymph nodes, or the thoracic wall (Figure 1F and Supplemental table S1). This metastatic behavior was even more pronounced in LSL-Kras;Cdkn2ab-/- mice, where 89% of the mice carried lung tumors that metastasized to mediastinal lymph nodes and the myocardium (Figure 1F and Supplemental table S1). These finding indicate that p15Ink4b deficiency leads to high-grade lung adenocarcinomas with aggressive behavior including the property to generate loco-regional metastasis.

Kras;Cdkn2ab null lung tumors display upregulation of proliferative markers

We determined the level of activity of targets of KRAS, which have been implicated in tumorigenesis, and of the mitotic marker phospho-Histone 3 (p-H3). LSL-Kras;Cdkn2a null and LSL-Kras;Cdkn2ab null tumors were diffusely positive for p-S6 and p-Erk1/2, with more intense staining in tumor segments with atypical nuclei and papillary morphology, while LSL-Kras;Cdkn2ab+/+ lung tumors were faintly positive for p-S6 and p-Erk1/2 (Figure 2A).

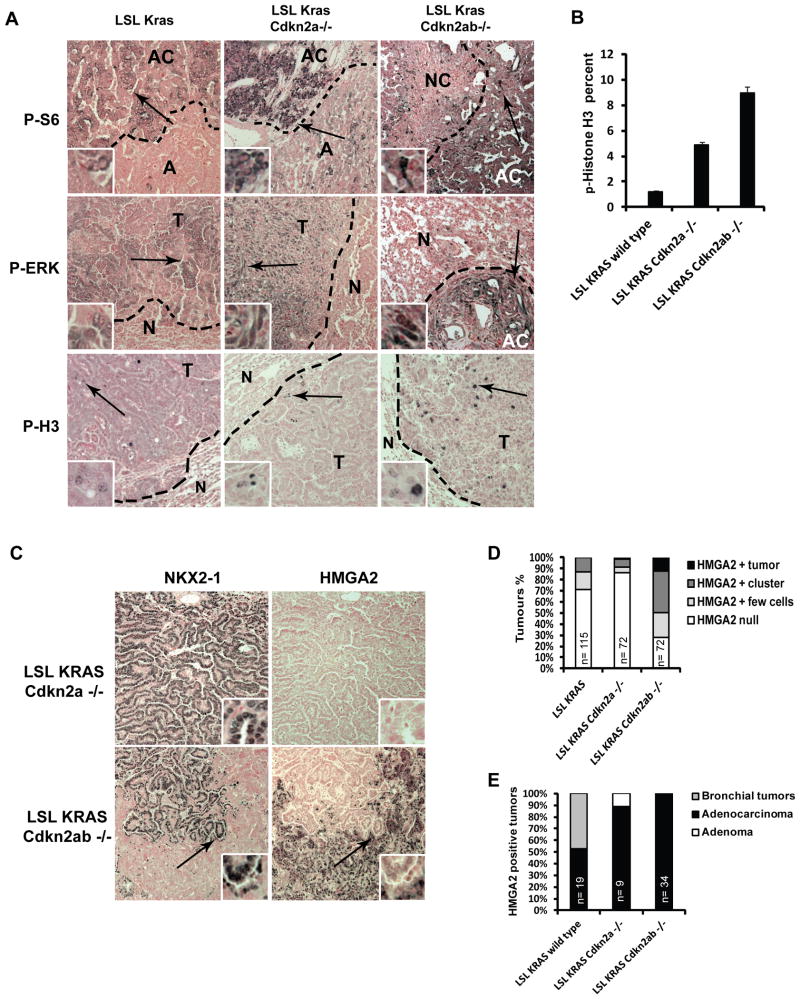

Figure 2. Loss of Cdkn2ab increases proliferation, and tumor progression in mutant Kras lung tumors.

(A) Images of lung tumors stained with the indicated antibodies (100X). Antibody staining is shown in brown, nuclear fast red counter-stain is pink-red. Arrows show location of inlets. A – Adenoma, AC – Adenocarcinoma, T – tumor, N - normal tissue. (B) Histogram of the percentage of p-H3 positive cells lung tumors. (C) Sections of lung tumors stained as indicated (100X). Arrows indicate the location of inlets. (D) Histogram representing percentage of lung tumors with the indicated HMGA2 staining pattern (refer to methods for scoring scale). (E) Anatomic location and classification of HMGA2 positive tumors. Number of tumors is indicated.

The staining pattern of p-H3 was genotype dependent: LSL-Kras;Cdkn2a-/- tumors stained positive for p-H3 mostly at the tumor edge. In contrast, LSL-Kras;Cdkn2ab-/- tumors stained positive throughout the tumor mass. Furthermore, the number of mitotic cancer cells increases significantly in LSL-Kras;Cdkn2ab-/- tumors as compared to Cdkn2a-/- and Cdkn2ab+/+ lung tumors (Figure 2A and B). We conclude that the loss of Cdkn2ab promotes cellular proliferation and progression of KRAS driven lung tumors.

Cdkn2ab deficiency leads to reduction of differentiation of KRASG12D driven lung tumors

To further characterize the lung tumors that develop in LSL-Kras;Cdkn2ab null mice, we evaluated the lung epithelial marker NK2.1 homeobox 1 (NKX2-1) and chromosomal high motility group protein HMGA2, which define the status of differentiation of lung adenocarcinoma driven by mutant KRAS in the mouse (31, 32). NKX2-1 is a master regulator of lung differentiation, which is expressed in the majority of human lung adenocarcinomas (33). Human lung tumors that are negative for NKX2-1 are poorly differentiated, display high-grade histological features and an aggressive behavior (33-35). NKX2-1 restrains lung cancer progression by enforcing a lung epithelial differentiation program by repressing the chromatin regulator HMGA2 (31, 32).

We found that lung tumors of LSL-Kras;Cdkn2ab+/+ and LSL-Kras;Cdkn2a-/- mice are predominately NKX2-1 positive and HMGA2 negative (Figure 2C, D and Supplementary Figure S2A). In contrast, about 21% of LSL-Kras;Cdkn2ab-/- tumors lose NKX2-1 completely (Supplemental Figure S2A). In addition, about 73% of LSL-Kras;Cdkn2ab-/- tumors increase their number of HMGA2 positive cells (Figure 2C-E and Supplementary Figure S2B). Finally, we also determined that the metastases that developed in Cdkn2a-/- and in Cdkn2ab-/- lung tumors stain positive for HMGA2 (Supplemental Figure S2C). This observation strongly suggests that HMGA2 positive lung tumors have metastatic potential.

These data indicate that complete loss of the Cdkn2ab locus significantly promotes lung cancer tumor progression in the mouse. These observations imply that p15INK4B provides an important tumor suppressor function in opposing mutant KRAS tumorigenesis.

Transgenic mouse model of genetically labeled cancer initiating cells

To characterize in better detail the biological consequence of Cdkn2ab deficiency in oncogenic Kras lung adenocarcinoma, we generated mice that allow the tagging and isolation of lung cancer cells. We took advantage of CCSP-rtTA;Tet-op-Kras mice, which carry a transgene encoding KrasG12D under the control of the tetracycline operator (Tet-op-Kras), and a transgene expressing the reverse tetracycline transactivator in the respiratory epithelium under the control of the Clara cell secretory protein promoter (CCSP-rtTA). Tet-op-Kras;CCSP-rtTA mice develop lung cancer with 100% penetrance when continuously exposed to doxycycline (doxy) (6).

To visualize mutant KRAS expressing lung epithelial cells, we crossed the Tet-op-Kras;CCSP-rtTA strain with mice that carry a transgene encoding histone H2B fused to green fluorescence protein (H2B-GFP) under the control of the tetracycline operator (tetO-HIST1H2BJ-GFP) (23). We determined that upon exposure to food pellets impregnated with doxy, Tet-op-Kras,CCSP-rtTA;tetO-HIST1H2BJ-GFP (Kras-GFP mice) transgenic mice express H2B-GFP in lung epithelial cells (Supplemental Figure 3A-C) with the characteristics of type II pneumocytes (Figure 3A).

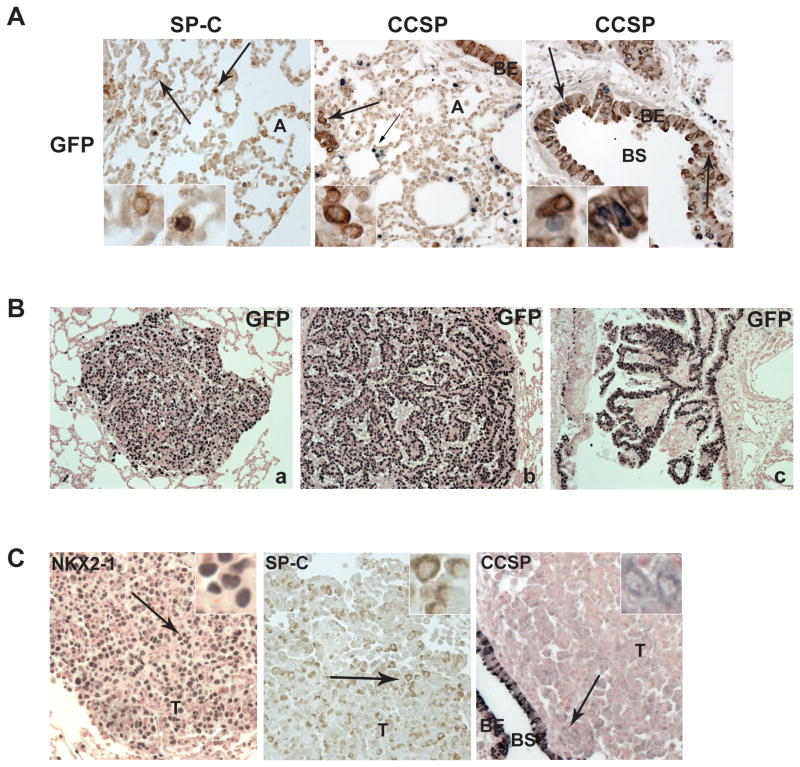

Figure 3. Lung epithelial cells and tumors genetically labeled by H2B-GFP.

(A) Lung sections stained with the indicated antibodies. H2B-GFP positive cells in the alveoli stain positive for SP-C suggesting that they are alveolar type II pneumocytes. H2B-GFP staining: black-grey, SP-C and CCSP staining: brown. Arrows indicated the location of the inlets. Magnification 200X. A. (B) Immunohistochemistry of lung tumors from Kras-GFP mice stained as indicated: a) adenoma, b) adenocarcinoma, c) bronchial tumor (100X). (C) Kras-GFP tumors stained as indicated. Arrows indicate the location of the inlets. Images are enlarged 200 fold. CCSP-rtTA transgene is expressed, albeit at low level, in lung cancer cells. These data independently confirm the observations of Fisher et al. regarding the pattern of expression of CCSP-rtTA (6).

When exposed continuously to doxy, Kras-GFP mice develop mutant KRAS lung tumors that are also positive for H2B-GFP (Figure 3B). Lung tumor cells showed predominantly nuclear NKX2-1 staining; and cytoplasmic SP-C staining (Figure 3C). Tumor cells were predominantly negative for CCSP but we detected faint CCSP expression in a portion of tumor cells as compared to the strong staining in the bronchiolar epithelial lining (Figure 3C). We conclude that this mouse model allows successful H2B-GFP tagging of lung cancer cells.

Cdkn2ab deficiency promotes the development of high-grade non-small cell lung carcinomas

We determined the effect of Cdkn2a or Cdkn2ab deficiency on lung tumorigenesis in Kras-GFP mice. Significantly, Kras-GFP ;Cdkn2ab-/- mice developed an increased number of tumors as well as an increased tumor burden 4.5 months after induction of mutant KRAS (Figure 4A, B and C). In this mouse model, loss of Cdkn2a resulted in an intermediate number of tumors and tumor burden at 4.5 months (Supplemental Figure S4A and B). We also observed an increase in tumor burden in Kras-GFP;Cdkn2ab-/- mice at time of death (Supplemental Figure S4C). These results indicate that Cdkn2ab loss promotes both mutant KRAS tumor initiation and progression.

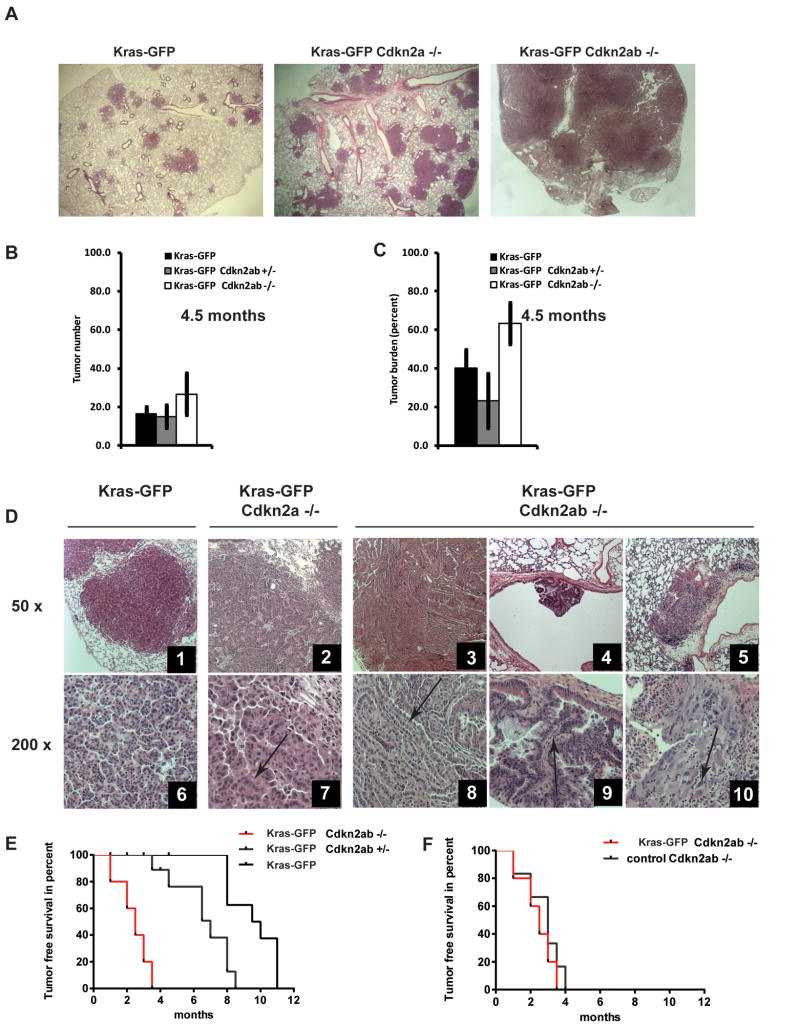

Figure 4. Loss of Cdkn2ab results in high-grade lung cancer and increased tumor burden.

(A) Representative lung section of mice of the indicated genotypes 4.5 months after doxy exposure (15X magnification). (B-C) Histograms show tumor number or burden in mice of the indicated genotype after 4.5 months of doxy. Note increased tumor number/burden in mutant Kras-GFP;Cdkn2ab-/- mice. (D) Lung tumors of the indicated genotypes. Arrows indicate areas with papillar features and atypical nuclei (panels 6, 7, 8, 9) or with poor differentiation (panel 10).

Tumors arose within the lung parenchyma and alveoli in all three genotypes (Figure 4D); however, in this model only Cdkn2ab null mice generated tumors that arose from the bronchial epithelia (Figure 4D, panels 4 and 9 and Supplemental Figure S4D). This observation suggests that Cdkn2ab loss reduces the threshold to develop oncogenic KRAS induced tumors in distal bronchioles. In addition, Cdkn2a or Cdkn2ab null mice developed lung tumors characterized by nuclear atypia and papillary structures (Figure 4D panels 2, 7 and 3,8 and Supplemental Figure S4D) that closely resembles aggressive human NSCLC (36, 37). Others and we described similar morphologic changes in lung adenocarcinomas of Cdkn2a null mice induced by the doxy regulated mutant Kras transgene (6, 9, 38).

Lung tumors of Cdkn2ab deficient mice show an increase in the number of cells stained positive for targets of activated KRAS, such as p-S6 ribosomal protein and p-ERK1/2 (Supplemental Figure S4E). These findings suggest that Cdkn2ab deficiency leads to increased proliferative activity. These features reproduced the characteristics of lung tumors developed in LSL-Kras;Cdkn2ab-/- mice.

Kras-GFP;Cdkn2ab+/+ mice had the longest survival, Kras-GFP;Cdkn2a-/- mice had an intermediate survival and Kras-GFP;Cdkn2ab-/- mice had the shortest survival among the three groups (Supplemental Figure S4G). These differences however were due mainly to sarcomas and lymphomas, which preclude the assessment of lung cancer-specific mortality (Supplemental Figure S4H and Supplemental Table S2).

H2B-GFP positive epithelial cells form colonies in vitro

To evaluate the properties of lung epithelial cells marked by H2B-GFP we obtained single cell suspensions from the lungs of Kras-GFP and CCSP-rtTA;tetO-HIST1H2BJ-GFP control transgenic mice (control-GFP mice). We found that one out of 85 H2B-GFP positive oncogenic KRAS expressing lung epithelial cells formed colonies whereas only 1 out of 150 GFP positive, but wild type Kras lung epithelial cells were able to do so (Supplemental Figure S5A and B). We did not detect any difference in the number of lung epithelial cells present in colonies of either control or mutant KRAS expressing GFP positive cells (Supplemental Figure S5C). This finding suggests that mutant KRAS promotes clonogenicity, but not cell proliferation under these conditions.

We were able to passage these cells up to 5 times onto feeder cultures, suggesting that they can be propagated in vitro and have short-term self-renewal abilities. Of note, similar colony formation ratios were reported for bronchoalveolar stem cells (BASC), putative epithelial stem cells present at the bronchoalveolar junction (39).

We were unable to propagate H2B-GFP positive cells obtained from the respiratory epithelium beyond 5 passages due to loss of viability. In contrast, H2B-GFP positive primary lung epithelial cells obtained from Kras-GFP;Cdkn2a-/- or Kras-GFP;Cdkn2ab-/- mice readily give rise to cell lines when grown as monolayer cultures in conventional tissue cultures plates and retain a subpopulation of H2B-GFP positive cells for up to 20 passages (Supplemental Figure S5D and E). Moreover, H2B-GFP positive cells are positive for lung epithelial markers and the cancer stem cell marker ALDH1A1 (Supplemental Figure S5F). As expected, only H2B-GFP positive cells express mutant Kras (Supplemental Figure S5G). Moreover, mutant Kras expression is doxy dependent and cannot be reinduced (Supplemental Figure S5H). Taken together, these data suggest that deficiency of the genes of the Cdkn2ab locus promote immortalization of the respiratory epithelial cells.

Loss of p15INK4B promotes mutant KRAS tumorigenesis in human lung cancer

To determine the frequency of the loss of genes of the CDKN2AB locus, we determined the mutation status of p15INK4B, p16INK4A and p14ARF in a panel of 23 human NSCLC lines which express mutant KRAS. For this purpose we used direct sequencing to detect point mutations and SNP analysis the detect gene copy number alteration (Table 1). We established that 6 of the cell lines carried homozygous deletions of CDKN2AB and 15 cell lines carried at least heterozygous deletion of CDKN2AB. Only two cell lines (HCC44 and H1155) did not lose a single copy of the CDKN2AB allele. We validated nullyzygosity of the CDKN2AB locus in A549 and H460 by quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 5A). These findings indicate that loss of function of all three tumor suppressors of CDKN2AB is a common event in human lung adenocarcinoma.

Table 1. CDKN2AB status of KRAS mutant non-small cell lung cancer cell lines.

CDKN2AB mutation status is indicated as WT – wild type, HOMO – homozygous loss, HET – heterozygous loss, MUT – KRAS mutation. Pathologic classification of cell lines is indicated as it was given at the time the cell lines were raised.

| Cell Line | Tumor Subtype | CDKN2AB Status | KRAS |

|---|---|---|---|

| A549 | Adenocarcinoma | HOMO | MUT |

| H460 | Large Cell | HOMO | MUT |

| H1944 | Adenocarcinoma | HOMO | MUT |

| HCC1171 | NSCLC | HOMO | MUT |

| HCC4017 | Large Cell | HOMO | MUT |

| HOP-62 | Adenocarcinoma | HOMO | MUT |

| H23 | Adenocarcinoma | HET | MUT |

| H157 | Squamous | HET | MUT |

| H358 | Adenocarcinoma | HET | MUT |

| H441 | Adenocarcinoma | HET | MUT |

| H1355 | Adenocarcinoma | HET | MUT |

| H1373 | Adenocarcinoma | HET | MUT |

| H1734 | Adenocarcinoma | HET | MUT |

| H2009 | Adenocarcinoma | HET | MUT |

| H2122 | Adenocarcinoma | HET | MUT |

| H2347 | Adenocarcinoma | HET | MUT |

| H2887 | NSCLC | HET | MUT |

| HCC366 | Adenosquamous | HET | MUT |

| HCC461 | Adenocarcinoma | HET | MUT |

| HCC515 | Adenocarcinoma | HET | MUT |

| Calu-6 | Adenocarcinoma | HET | MUT |

| H1155 | Large Cell | WT | MUT |

| HCC44 | Adenocarcinoma | WT | MUT |

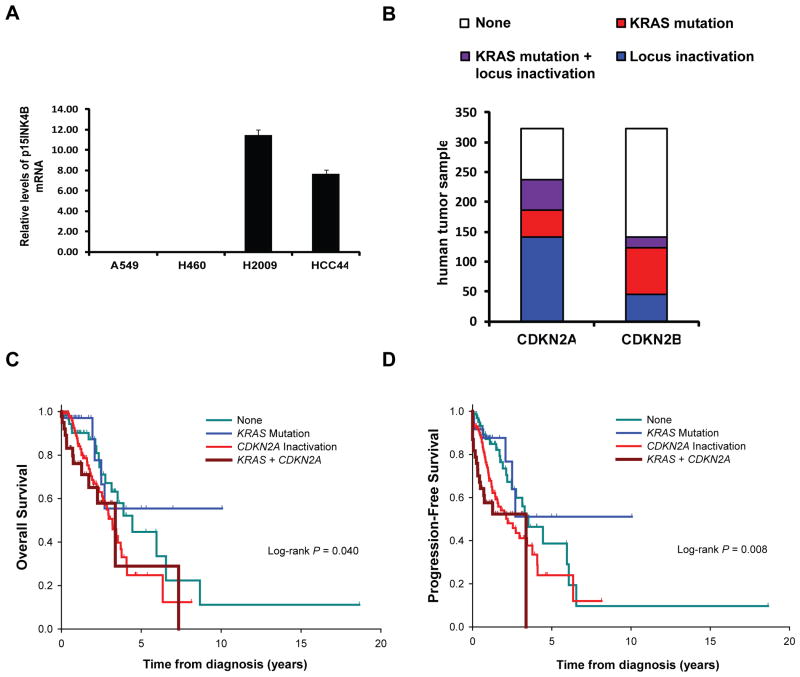

Figure 5. CDKN2AB status in human mutant KRAS lung adenocarcinoma.

(A) Histogram of p15INK4B mRNA in NSCLC cell lines normalized to GAPDH. (B) Histogram shows the frequency of KRAS mutations and CDKN2A or CDKN2AB inactivation in lung adenocarcinoma in the TCGA data set. (C) Overall survival and (D) progression-free survival curves of patients with lung adenocarcinoma carrying mutant KRAS and/or inactivation of CDKN2A.

We next analyzed patient data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. Data with mutation, copy number, and methylation was available for 323 lung adenocarcinoma patients and showed that 30% (n=96) had oncogenic KRAS mutations. In addition, 51 out of the 96 patients (53%) with KRAS mutations also had two-hit CDKN2A inactivation by mutation, chromosomal deletion, and/or promoter methylation. Of these patients, 17 (18%) also showed inactivation in the CDKN2B locus by homozygous deletions. None of the patients in this database showed inactivation of CDKN2B but not of CDKN2A. These data indicate that the loss of the CDKN2AB locus is a common occurrence in human non-small cell lung cancer (Figure 5B). Notably, deficiency of CDKN2A is associated with higher pathologic stage (Supplemental table S3), poorer overall survival (Figure 5C) and progression-free survival (Figure 5D) in mutant KRAS lung adenocarcinoma patients. While there is a tendency to poorer progression-free survival with inactivation of CDKN2B in addition to CDKN2A (P=0.19), this difference was not significant. Anyway, inactivation of either CDKN2A or CDKN2AB is associated with poorer progression-free survival and overall survival (Supplemental Figures S6A and B) independently of the KRAS mutation status.

p15INK4B expression promotes growth arrest in human lung cancer cells

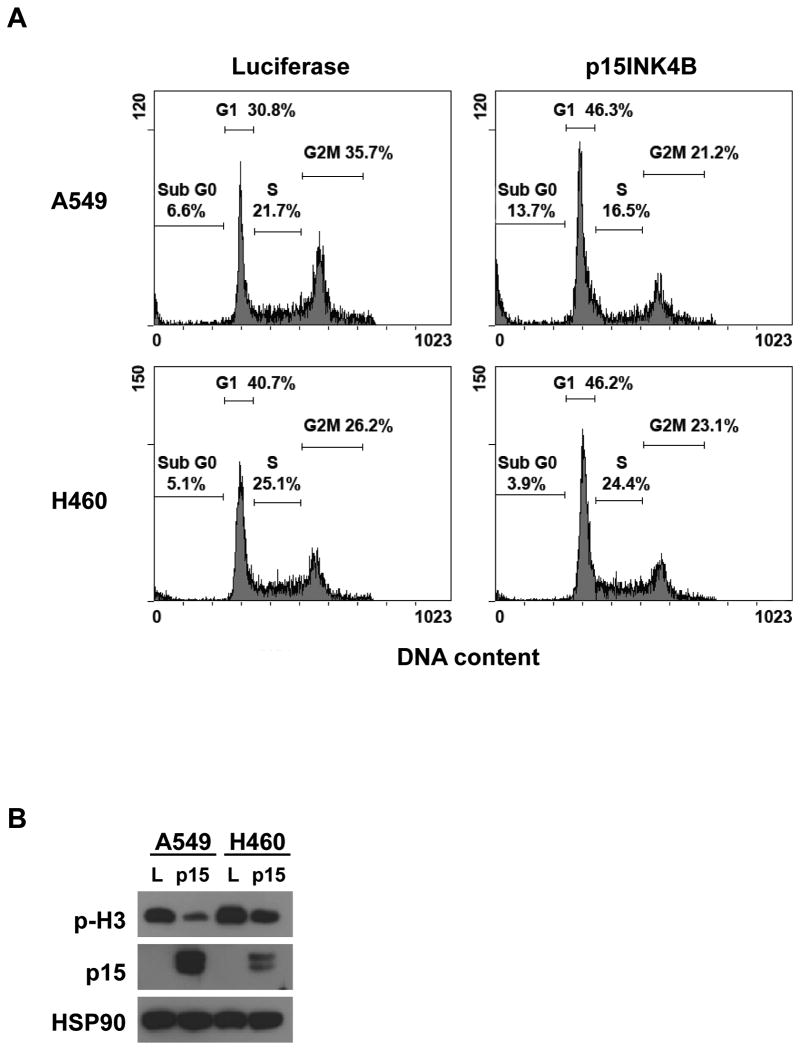

To determine the functional effect of p15INK4B expression in vitro, we ectopically expressed 15INK4B in mutant KRAS human lung cancer cell lines that also carry homozygous deletions of the CDKN2AB locus. We determined that reintroduction of 15INK4B leads to an increase in the percentage of A549 and H460 cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (Figure 6A). Furthermore, we noticed a significant increase of the percentage of subdiploid cells in A549 cells, which indicate the presence of apoptosis. Western blot analysis confirmed that expression of p15INK4B downregulates the phosphorylation of mitotic marker p-H3 (Ser 10) (Figure 6B). These results suggest that the expression of p15INK4B promotes a tumor suppressor program that counteracts the proliferative effects of mutant KRAS in NSCLC cells.

Figure 6. Reintroduction of p15INK4B in CDKN2AB deficient lung cancer cell lines causes in growth arrest and apoptosis.

(A) Cell cycle analysis of A549 and H460 cells after 72h of luciferase or p15INK4B expression. Both cell lines show an increase in the G1 phase of the cell cycle. A549 cells also showed an increase in Sub-G1 fraction suggesting a portion of cells undergoes apoptosis. (B) Western blot analysis of A549 and H460 cells transduced as indicated. L: luciferase.

Discussion

Recent technical advancements have allowed a systematic evaluation of statistically recurrent somatic mutations in NSCLC (2, 3). This data set holds the promise to better understand lung tumorigenesis and to identify novel treatments for lung cancer patients.

In this study we show that genetic inactivation of the CDKN2A and CDKN2B loci is a common event in mutant KRAS lung adenocarcinoma. By analyzing the TCGA database we determined that inactivation of CDKN2A by either somatic mutation, chromosomal deletion, and/or promoter hypermethylation, and inactivation of CDKN2B by homozygous deletion occur in about 50% and 20% of human lung adenocarcinomas, respectively. Previous reports did not have sufficient power to determine whether inactivation of the genes of CDKN2AB occurs with significant frequency in mutant KRAS lung cancer (2, 40). By analyzing the large TCGA sample, it is apparent that inactivation of CDKN2AB occurs at a significantly higher frequency than previously noted. Furthermore, we noticed that loss of CDKN2B rarely, if ever, occurs in the absence of CDKN2A somatic inactivation. Our analysis of the TCGA data set also indicates that loss of CDKN2A is associated with higher stage, higher incidence of metastasis, and consequently, decreased overall survival in mutant KRAS lung cancer patients. These findings have significant clinical implications since they suggest that mutant KRAS lung cancers with two-hit inactivation of CDKN2A identify a subset of patients with high-risk disease. In this regard it is of interest that these patients could benefit from treatment with focal adhesion kinase inhibitors (9).

We recently reported that expression of oncogenic KRAS in the respiratory epithelium significantly reduced the longevity of p16Ink4a/p19Arf null mice (9). We observed a further increase in lung cancer mediated mortality in mutant Kras mice conditionally deficient in the entire Cdkn2ab locus. This observation suggests a model whereby p15INK4B loss confers a selective advantage to tumor cells that have lost p16INK4a and p14ARF. However, we did not detect a worse clinical outcome in patients with mutant KRAS lung cancers with loss of CDKN2AB as compared to patients with lung cancers mutant for KRAS and CDKN2A. We reason that this discrepancy could be due several variables including insufficient sample size of the TCGA data set or the presence of concurrent mutations that affect the phenotype of human cancer that are not present in genetically engineered mice.

We determined histologically that Cdkn2a deficiency leads to a higher percentage of high-grade lung tumors in Tet-o-Kras mice than in LSL-Kras mice, while the lung tumor phenotype of mutant Kras;Cdkn2ab null mice is consistent between the two mouse models. It is likely that these differences are either due to the strength of the promoters used to express mutant Kras or to the fact that we exposed mice to doxy at 4 weeks of age to attempt to obtain lung tumors prior to the emergence of tumors in other sites. We reason that LSL-Kras mice, owing to the fact that mutant Kras is expressed from the endogenous promoter, model more closely mutant KRAS tumorigenesis.

Our in vivo cell-tracking experiments are consistent with a recent report indicating that a subset of alveolar type II cell co-expressing CCSP and SP-C give rise to lung adenocarcinomas upon mutant KRAS expression (41). The observation that loss of Cdkn2ab promotes the clonogenic ability of lung epithelial cells and their ability to readily give rise to cell lines supports the notion that Cdkn2ab regulates cell proliferation. This assertion is further supported by our observation that reintroduction of p15INK4B induces antiproliferative effects in human NSCLC lines. We also noticed that once mutant Kras was extinguished in Cdkn2ab null lung epithelial, it could no longer being induced. This observation leads to the speculation that mutant KRAS facilitates the maintenance of a cell state permissive the expression of the CC10 promoter driving rtTA or the accessibility of the Tet-op element driving mutant KRAS.

Overall, our data provide new genetic evidence that the loss of the three genes residing in CDKN2AB promotes mutant KRAS lung tumorigenesis by fostering cellular proliferation, cancer cell differentiation and metastatic behavior. We propose that mutant Kras;Cdkn2ab null mice provide a platform to accurately model aggressive mutant Kras lung adenocarcinoma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Diego Castrillon of the Department of Pathology, UTSW for providing the Vasa-Cre transgenic mouse, Dr. Anton Berns (Netherlands Cancer Institute, Netherlands) for the Ink4ab-/- conditional mouse, Angie Mobley (UTSW Flow Cytometry Core), Rachel Ramirez (Scaglioni's Lab) and John Shelton (Histology Core UTSW) for technical assistance. We thank Drs. John Minna, Adi Gazdar, John Heymach and Ignacio Wistuba for providing NSCLC lines and access to their expression and genomic profiles (supported by NCI SPORE P50CA70907).

Financial Support: American Cancer Society Scholar Award 13-068-01-TBG, CDMRP LCRP Grant LC110229, UT Southwestern Friends of the Comprehensive Cancer Center, the Gibson Foundation, and (PPS). NRSA Award F32CA154237 from the National Cancer Institute (KS). CPRIT-NGS RP 110708 and NCI SPORE P50CA70907 (LG).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.ACSI ACSI. Cancer Facts and Figures. 2013 Cancer Facts and Figures 2013; Available from: http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsfigures/cancerfactsfigures/cancer-facts-figures-2013.

- 2.Imielinski M, Berger AH, Hammerman PS, Hernandez B, Pugh TJ, Hodis E, et al. Mapping the hallmarks of lung adenocarcinoma with massively parallel sequencing. Cell. 2012;150:1107–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012;489:519–25. doi: 10.1038/nature11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy MA, Lovly CM, Pao W. Translating genomic information into clinical medicine: lung cancer as a paradigm. Genome Res. 2012;22:2101–8. doi: 10.1101/gr.131128.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Grabocka E, Bar-Sagi D. RAS oncogenes: weaving a tumorigenic web. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:761–74. doi: 10.1038/nrc3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher GH, Wellen SL, Klimstra D, Lenczowski JM, Tichelaar JW, Lizak MJ, et al. Induction and apoptotic regression of lung adenocarcinomas by regulation of a K-Ras transgene in the presence and absence of tumor suppressor genes. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3249–62. doi: 10.1101/gad.947701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson L, Mercer K, Greenbaum D, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Tuveson DA, et al. Somatic activation of the K-ras oncogene causes early onset lung cancer in mice. Nature. 2001;410:1111–6. doi: 10.1038/35074129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pao W, Wang TY, Riely GJ, Miller VA, Pan Q, Ladanyi M, et al. KRAS mutations and primary resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konstantinidou G, Ramadori G, Torti F, Kangasniemi K, Ramirez RE, Cai Y, et al. RHOA-FAK is a required signaling axis for the maintenance of KRAS-driven lung adenocarcinomas. Cancer discovery. 2013;3:444–57. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Xiong Y, Yarbrough WG. ARF promotes MDM2 degradation and stabilizes p53: ARF-INK4a locus deletion impairs both the Rb and p53 tumor suppression pathways. Cell. 1998;92:725–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamijo T, Weber JD, Zambetti G, Zindy F, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. Functional and physical interactions of the ARF tumor suppressor with p53 and Mdm2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8292–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamb A, Gruis NA, Weaver-Feldhaus J, Liu Q, Harshman K, Tavtigian SV, et al. A cell cycle regulator potentially involved in genesis of many tumor types. Science. 1994;264:436–40. doi: 10.1126/science.8153634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruas M, Peters G. The p16INK4a/CDKN2A tumor suppressor and its relatives. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1378:F115–77. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(98)00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gil J, Peters G. Regulation of the INK4b-ARF-INK4a tumour suppressor locus: all for one or one for all. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:667–77. doi: 10.1038/nrm1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherr CJ. Divorcing ARF and p53: an unsettled case. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:663–73. doi: 10.1038/nrc1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ji H, Ramsey MR, Hayes DN, Fan C, McNamara K, Kozlowski P, et al. LKB1 modulates lung cancer differentiation and metastasis. Nature. 2007;448:807–10. doi: 10.1038/nature06030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharpless NE, Bardeesy N, Lee KH, Carrasco D, Castrillon DH, Aguirre AJ, et al. Loss of p16Ink4a with retention of p19Arf predisposes mice to tumorigenesis. Nature. 2001;413:86–91. doi: 10.1038/35092592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng XH, Lin X, Derynck R. Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4 cooperate with Sp1 to induce p15(Ink4B) transcription in response to TGF-beta. EMBO J. 2000;19:5178–93. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.19.5178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latres E, Malumbres M, Sotillo R, Martin J, Ortega S, Martin-Caballero J, et al. Limited overlapping roles of P15(INK4b) and P18(INK4c) cell cycle inhibitors in proliferation and tumorigenesis. EMBO J. 2000;19:3496–506. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krimpenfort P, Ijpenberg A, Song JY, van der Valk M, Nawijn M, Zevenhoven J, et al. p15Ink4b is a critical tumour suppressor in the absence of p16Ink4a. Nature. 2007;448:943–6. doi: 10.1038/nature06084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2:401–4. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 6:pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tumbar T, Guasch G, Greco V, Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Rendl M, et al. Defining the epithelial stem cell niche in skin. Science. 2004;303:359–63. doi: 10.1126/science.1092436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson EL, Willis N, Mercer K, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Montoya R, et al. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3243–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aguirre AJ, Bardeesy N, Sinha M, Lopez L, Tuveson DA, Horner J, et al. Activated Kras and Ink4a/Arf deficiency cooperate to produce metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3112–26. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DuPage M, Dooley AL, Jacks T. Conditional mouse lung cancer models using adenoviral or lentiviral delivery of Cre recombinase. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1064–72. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pena-Llopis S, Vega-Rubin-de-Celis S, Liao A, Leng N, Pavia-Jimenez A, Wang S, et al. BAP1 loss defines a new class of renal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:751–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gandhi J, Zhang J, Xie Y, Soh J, Shigematsu H, Zhang W, et al. Alterations in genes of the EGFR signaling pathway and their relationship to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor sensitivity in lung cancer cell lines. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byers LA, Diao L, Wang J, Saintigny P, Girard L, Peyton M, et al. An epithelial-mesenchymal transition gene signature predicts resistance to EGFR and PI3K inhibitors and identifies Axl as a therapeutic target for overcoming EGFR inhibitor resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:279–90. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rabellino A, Carter B, Konstantinidou G, Wu SY, Rimessi A, Byers LA, et al. The SUMO E3-ligase PIAS1 regulates the tumor suppressor PML and its oncogenic counterpart PML-RARA. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2275–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snyder EL, Watanabe H, Magendantz M, Hoersch S, Chen TA, Wang DG, et al. Nkx2-1 represses a latent gastric differentiation program in lung adenocarcinoma. Mol Cell. 50:185–99. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winslow MM, Dayton TL, Verhaak RG, Kim-Kiselak C, Snyder EL, Feldser DM, et al. Suppression of lung adenocarcinoma progression by Nkx2-1. Nature. 473:101–4. doi: 10.1038/nature09881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barletta JA, Perner S, Iafrate AJ, Yeap BY, Weir BA, Johnson LA, et al. Clinical significance of TTF-1 protein expression and TTF-1 gene amplification in lung adenocarcinoma. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:1977–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berghmans T, Paesmans M, Mascaux C, Martin B, Meert AP, Haller A, et al. Thyroid transcription factor 1--a new prognostic factor in lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1673–6. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, Nicholson AG, Geisinger K, Yatabe Y, et al. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society: international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma: executive summary. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 8:381–5. doi: 10.1513/pats.201107-042ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, Nicholson AG, Geisinger KR, Yatabe Y, et al. International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:244–85. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nikitin AY, Alcaraz A, Anver MR, Bronson RT, Cardiff RD, Dixon D, et al. Classification of proliferative pulmonary lesions of the mouse: recommendations of the mouse models of human cancers consortium. Cancer research. 2004;64:2307–16. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Konstantinidou G, Bey EA, Rabellino A, Schuster K, Maira MS, Gazdar AF, et al. Dual phosphoinositide 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin blockade is an effective radiosensitizing strategy for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer harboring K-RAS mutations. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7644–52. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim CF, Jackson EL, Woolfenden AE, Lawrence S, Babar I, Vogel S, et al. Identification of bronchioalveolar stem cells in normal lung and lung cancer. Cell. 2005;121:823–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, Mardis ER, McLellan MD, Cibulskis K, et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455:1069–75. doi: 10.1038/nature07423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu X, Rock JR, Lu Y, Futtner C, Schwab B, Guinney J, et al. Evidence for type II cells as cells of origin of K-Ras-induced distal lung adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:4910–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112499109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.