Abstract

Redox homeostasis is especially important in the brain where high oxygen consumption produces an abundance of harmful oxidative by-products. Glutathione (GSH) is a tripeptide non-protein thiol. It is the central nervous system’s most abundant antioxidant, and the master controller of brain redox homeostasis. The glutamate transporters, System xc− (SXC) and the Excitatory Amino Acid Transporters (EAAT), play important, synergistic roles in the synthesis of GSH. In glial cells, SXC mediates the uptake of cystine, which after intracellular reduction to cysteine, reacts with glutamate during the rate-limiting step of GSH synthesis. EAAT3 mediates direct cysteine uptake for neuronal GSH synthesis. SXC and EAAT work in concert in glial cells to provide two intracellular substrates for GSH synthesis, cystine and glutamate. Their cyclical basal function also prevents a buildup of extracellular glutamate, which SXC releases extracellularly in exchange for cystine uptake. Maintaining extracellular glutamate homeostasis is critical to prevent neuronal toxicity, as well as glutamate-mediated SXC inhibition, of which each could lead to a depletion of intracellular GSH and loss of cellular redox control. Many neurological diseases show evidence of GSH dysfunction, and increased GSH has been widely associated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy resistance of gliomas. We present evidence suggesting that gliomas expressing elevated levels of SXC are more reliant on GSH for growth and survival. They have an increased inherent radiation resistance, yet inhibition of SXC can increase tumor sensitivity at low radiation doses. GSH depletion through SXC inhibition may be a viable mechanism to enhance current glioma treatment strategies and make tumors more sensitive to radiation and chemotherapy protocols.

Keywords: Redox, Glutathione (GSH), System xc− (SXC), Excitatory Amino Acid Transporter (EAAT), Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), Glioma

Introduction

Many important biological processes involve redox reactions, and as a result, produce potentially dangerous byproducts. Oxidative phosphorylation, or oxidative metabolism, provides brain cells with most of their energy requirements. In fact, human brain cells use approximately 20% of the total oxygen consumed by the body, although the brain only makes up 2% of body weight1. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are continuously generated as a result of this large usage of oxygen, and therefore mechanisms are required to regulate the redox state of the brain. An unbalanced redox state and buildup of reactive oxygen species results in cell death and detrimental consequences for the brain.

Oxidative stress occurs as a result of an imbalance between oxidant production and neutralization by cellular antioxidants. ROS, as free radical species, are highly reactive compounds. If uncontrolled, they create DNA damage and protein/enzyme oxidation, which leads to cellular dysfunction and death2. A number of characteristics of the brain make it more vulnerable to oxidative stress. In addition to the amount of ROS produced by its high oxygen consumption1, some areas of the brain contain a high content of iron3, which catalyzes ROS generation4, and the large amount of unsaturated fatty acid lipids found in the brain are targets for lipid peroxidation5,6. Surprisingly, the levels of activity of common enzymes that catalyze the neutralization of free radicals, specifically superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), are lower in the brain than in other organs such as the liver and kidney7.

Common pathologies including neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) involve ROS-mediated oxidative stress as part of their etiology4,8–12. Even normal aging may be, at least in part, due to ROS. The “free radical theory of aging” hypothesizes that free radical induced cellular damage builds up over time, ultimately resulting in aging and death [see 13 for more on this topic]. Many mechanisms exist to regulate redox homeostasis. Here, we focus on the main mechanisms of redox control in the brain. We review the role of glutamate transporters in the production of the intracellular antioxidant glutathione (GSH) and its importance in redox homeostasis. We also discuss the role of glutamate transporter mediated redox imbalance in disease, and present new evidence suggesting their involvement in the radiation resistance of gliomas.

Redox Regulation in the Brain

Reactive oxygen species are generated in cells by the mitochondrial respiratory chain, which occurs on the inner mitochondrial membrane14–16. Interestingly, although most cancer cells are thought to primarily rely on glycolysis for energy production17, they produce an even higher level of ROS than normal cells18. Different theories exist as to how cancer cells produce ROS, including enhanced metabolism19, mitochondrial mutations and malfunction20, and chronic inflammation21. Regardless, the production of ROS in both non-malignant and malignant cells necessitates the production of intracellular antioxidants to neutralize these free radicals to prevent cell death.

Glutathione

Glutathione (GSH; γ-L-glutamyl-L-cysteinylglycine) is an important non-protein thiol that is found in all organs including the brain 22–25. It is the most abundant antioxidant in the central nervous system (CNS), and is found in the brain at concentrations around 1–3 mM4. In addition to its antioxidant role, GSH has many non-antioxidant functions. Some of these roles include storage and transport of cysteine26, regulation of apoptosis27–29, cell proliferation30, signal transduction31, and immune response32. As a thiol, it consists of three amino acids: L-cysteine (Cys), L-glutamate (Glu), and L-glycine (Gly). γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase mediates the rate-limiting step of GSH synthesis, combining Glu and Cys to form γ-glutamylcysteine (γGluCys). Glutathione synthetase then incorporates Gly to form GSH. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is required for the activity of both of these enzymes10,26,33. Regulation of GSH synthesis is accomplished through a feedback mechanism, where GSH regulates the synthesis of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase13, and, in turn maintains balance of GSH synthesis and consumption.

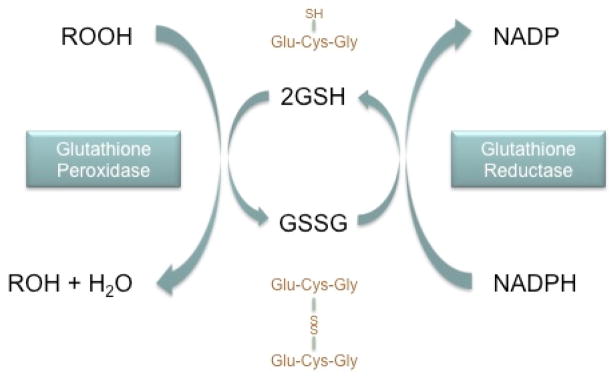

Intracellularly, GSH undergoes both enzymatic and non-enzymatic reactions during the detoxification of ROS. Non-enzymatically, GSH interacts directly with superoxide anions, hydroxyl radicals, and nitric oxide4. Enzymatically, GSH detoxifies peroxidases in a reaction mediated by glutathione peroxidase (Fig. 1). During this reaction GSH is oxidized to glutathione disulfide (GSSG). Glutathione reductase catalyzes the regeneration of GSH, forming a glutathione redox cycle34. In turn, glutathione reductase relies on nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) to reduce GSSG back to GSH. The redox status of cells depends on the ratio of reduced and oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG). Under normal conditions the reduced form exceeds the oxidized form by a ratio of nearly 1:100, however, under oxidative stress conditions, this ratio can be reduced to values as low as 1:125. As oxidative stress is neutralized, GSSG is regenerated to GSH, and the homeostatic ratio is re-established.

Figure 1. Intracellular GSH/GSSG Redox Cycle.

Glutathione (GSH) mediates the detoxification of reactive oxygen species (represented by the generic peroxide, ROOH) through an enzymatic reaction involving glutathione peroxidase. The sulfhydryl, or thiol, group (SH) serves as the proton donor in these reactions. GSH donates a reducing equivalent (H+ and e−) and in turn is converted to its oxidized form, glutathione disulfide (GSSG), which is created by the formation of a disulfide bond between two GSH molecules. GSSG is then reduced back to GSH by the enzyme glutathione reductase, which relies on NAPDH as an electron donor. The GSH:GSSG ratio indicates the redox state of cells. In healthy cells, greater than 90% of the glutathione is in the reduced GSH form. Oxidative stress can be indicated by a decrease in this ratio.

GSH is a critical molecule in the CNS that protects against oxidative stress induced cellular damage. Its loss is associated with brain cell death35. Glutathione is found in neurons and glia4,36–38, including astrocytes4, oligodendrocytes39 and microglia40. Evidence suggests neurons and glial cells are all vulnerable to ROS damage and that they all rely upon glutathione-mediate detoxification for protection [see 4 for a review on the role of glutathione in different brain cells]. Astrocytes are thought to contain the highest concentrations of glutathione in the brain41, and are therefore considered to play the largest role in ROS detoxification42–44. In culture, astrocytes protect neurons and oligodendrocytes against many toxic compounds45–48, further supporting the idea that astrocytes are the main regulators of oxidative stress in the brain.

Astrocytes extend their protection to neuronal cells through the export of GSH into the extracellular space. Neurons rely on extracellular cysteine for their synthesis of GSH22,49,50 and this cysteine is provided by cysteine-precursors from astrocytic glutathione release51. The export of GSH is mediated by a family of multidrug resistance proteins (MRPs)52–54. Once released, astroglial ectoenzyme γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γGT) acts on GSH, creating a CysGly compound55. Aminopeptidase N (ApN) then hydrolyzes CysGly to individual amino acids Cys and Gly56, which are both then available for import into neurons.

Glutamate Transporters

System xc−

The GSH/GSSG redox cycle uses and recycles intracellular GSH. However, since some intracellular reactions consume GSH and it is released from cells for extracellular functions, intracellular GSH levels would become depleted if not regularly synthesized4. Intracellular GSH synthesis requires availability of its amino acid precursors, with the incorporation of cysteine being rate limiting. Cystine (Cys2) is a dimeric amino acid that is formed by a disulfide bond between two cysteine molecules. Cysteine is not stable extracellularly due to oxidizing conditions that favor cystine formation. However, once cystine is imported, intracellular conditions support the rapid reduction of Cys2 to Cys57, providing substrate for GSH synthesis.

Cystine is taken up into cells by a glutamate transporter called System xc− (SXC) (Fig. 2). SXC is a Na+-independent, Cl−-dependent cystine/glutamate exchanger. The uptake of cystine is coupled to the release of glutamate extracellularly in a 1:1, electroneutral manner58. Belonging to the heteromeric amino acid transporter (HAT) family, SXC is composed of two subunits coupled by a disulfide bridge. The light subunit, xCT, confers transporter activity and the heavy subunit, CD98 (or 4F2hc), regulates its trafficking to the cell membrane. CD98 is constitutively membrane-expressed, and both subunits must be on the membrane and coupled to comprise a functional transporter 59.

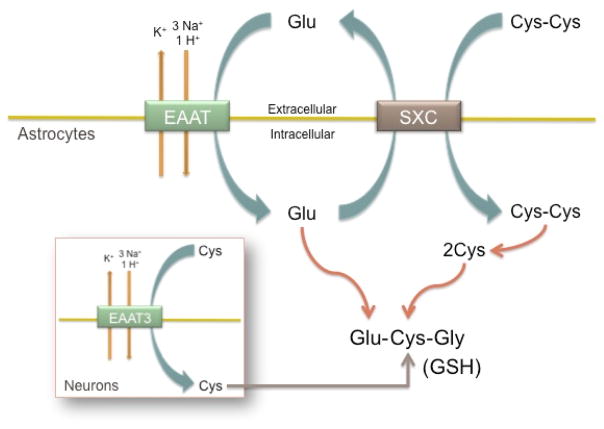

Figure 2. SXC and EAAT Cystine/Glutamate Cycle.

System xc− (SXC) and the Excitatory Amino Acid Transporter (EAAT) glutamate transporters work together to provide substrate for glutathione (GSH) synthesis. SXC mediates cystine (Cys-Cys) uptake in exchange for glutamate (Glu) release. Cys-Cys is reduced by the intracellular environment to cysteine (Cys), and is can then react with Glu and Gly to form GSH. EAAT mediate glutamate uptake, providing both substrate for GSH synthesis and substrate for SXC-mediated Cys-Cys uptake. These transporters synergize to provide intracellular Glu and Cys for GSH-mediate redox control. Direct cysteine uptake through the EAAT3 (EAAC1) glutamate transporter provides the rate limiting substrate for intracellular GSH in neurons.

In the brain, astrocytes predominately express SXC, however, oligodendrocytes 60, microglia 61, and immature cortical neurons 62, have also been found to have SXC expression as well. The main function of SXC is importing cystine for GSH synthesis. As an inducible transporter 63, cells are able to increase SXC expression and activity when increased intracellular redox control is required 24. Oxidative stress or electrophiles induce xCT expression by activating an Antioxidant Response Element (ARE) or Electrophile Reponse Element (EpRE) promoter region, and xCT can then be shuttled to the membrane, allowing increased cystine uptake 59. SXC may also protect cells against oxidative stress by driving an efficient cysteine/cystine redox cycle. This cycle changes the extracellular redox state from an oxidized to reduced state by releasing cysteine64. Studies suggesting that this cycle is important in redox control found xCT overexpression increases cysteine concentrations both intra- and extra-cellularly64,65. These studies argue that the cystine/cysteine cycle is itself an important redox system. However, more work needs to be done on this topic to determine its true significance in redox control, especially in the brain.

Excitatory Amino Acid Transporters

The Excitatory Amino Acid Transporters (EAAT) are a family of high-affinity Na+-dependent glutamate transporters. Electrogenic transport of glutamate is coupled to the movement of 3 Na+ and 1 H+ inward, and K+ outward (Fig. 2). There are five cloned members: EAAT1/GLAST, EAAT2/GLT1, EAAT3/EAAC1, EAAT4 and EAAT5. These transporters are found on neurons and glia, and are responsible for maintaining low extracellular glutamate levels to prevent aberrant glutamate signaling and toxicity66. EAAT2/GLT1 is the primary astrocytic glutamate transporter and accounts for nearly 1% of protein in the brain67. As the most abundant glutamate transporter, it is responsible for most of the glutamate uptake in the brain68,69. EAAT1/GLAST is also astrocytic, and EAAT5 is primarily located in retinal cells. EAAT3/EAAC1 and EAAT4 are both neuronal glutamate transporters, however, EAAT4 is mainly expressed in Cerebellar Purkinje cells66,70,71.

EAAT glutamate transporters directly influence redox homeostasis in a similar manner to SXC. As the primary neuronal glutamate transporter, EAAT3 reclaims extracellular glutamate after its release during synaptic signaling72. In addition however, EAAT3 mediates cysteine uptake73 and has been shown to do so in neuronal cultures74. Cysteine is present at much lower levels than glutamate or glycine in neurons75; therefore EAAT3 supplies neurons with the rate limiting substrate for GSH synthesis (Fig. 2; inset). EAAT3 knockout mice have decreased neuronal GSH and increased neuronal oxidative stress, which can be reversed with supplementation of the membrane-permeate cysteine pro-drug N-acetylcysteine (NAC)76,77.

Although some studies have detected xCT expression in cerebral cortex neurons60,78, it is thought that neurons preferentially utilize cysteine, not cystine, for synthesis of intracellular GSH10,22,49,79. Cysteine is rate limiting for neuronal GSH synthesis and down-regulation of EAAT3 function increases neuronal vulnerability to oxidative stress, both in vitro and in vivo75. In one study, EAAT3 knockout mice demonstrated a greater number of degenerating neurons three days after induced ischemia, which was normalized if NAC was administered as a pre-treatment, further supporting the importance of EAAT3-mediated cysteine uptake in neuronal antioxidant function80. Additionally, EAAT3 has a much higher affinity for cysteine than cystine73, which supports the finding that neurons rely upon cysteine, not cystine, import for GSH synthesis. Therefore, in the non-pathological brain, EAATs mediate glutamate uptake in astrocytes and neurons, and EAAT3 mediates cysteine uptake for GSH synthesis in neurons. EAAT3 serves as the link between astrocytic GSH release and neuronal GSH synthesis, by importing cysteine released from glutathione breakdown extracellularly.

In addition to this direct effect of glutamate transporters on glutathione production, they also work in concert with SXC to create a cycling of cystine and glutamate that supports redox homeostasis (Fig. 2). The uptake of cystine through SXC requires glutamate release, which is balanced by glutamate uptake58,81. This synergism creates a resting-state cycling of cystine and glutamate, which prevents intracellular cystine depletion and ensures no net glutamate release due to SXC activity72. Since glutamate acts as an inhibitor of SXC62, a buildup of extracellular glutamate can deplete cells of GSH. Therefore EAAT support SXC function by reducing extracellular glutamate to prevent inhibition of cystine transport into cells72.

Glutamate & Calcium Homeostasis

Glutamate is an important signaling molecule in the CNS and is abundant in the brain. However, it has the potential to be toxic and therefore the majority of it is contained intracellularly 66. Glutamatergic synapses are surrounded by astrocytic processes expressing EAAT2 and can quickly remove the glutamate released from the extracellular space 82,83. Glutamate transporters are also located pre- and extra-synaptically to contain any glutamate escaping the synaptic cleft 83.

Additionally, astrocytic glutamine transporters, or the sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporters (SNAT), also play an important role in maintaining glutamate homeostasis by transporting glutamine to neurons, from which they are able to re-synthesize glutamate 84. Since neurons lack pyruvate carboxylase, the enzyme required to synthesize glutamate from lactose or glucose 85, they depend on astrocytic recycling of glutamate. Astrocytes convert glutamate, using glutamine synthetase, to glutamine 86, which is then released through SNATs. Glutamine can be taken up by neurons and converted back to glutamate through neuronal glutaminase 87,88. SNAT transporters are tightly coupled to EAAT function, allowing astrocytes to carefully regulate glutamate recycling without increasing extracellular concentrations.

Increased extracellular glutamate creates neurotoxicity by overstimulation of the N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors on neurons, causing sustained elevations in intracellular Ca2+ 40. Increases in intracellular Ca+ initiates downstream signaling cascades89 that form ROS such as superoxide anions (O2−), hydroxyl radicals (OH•), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)90,91. Additionally, dysregulation of Ca2+ signaling and oxidative stress enhance each other, ultimately leading to Ca2+-dependent activation of intracellular proteases and phospholipases, and disruption of the mitochondrial membrane and release of more ROS and Ca2+ 89. The rapid and overwhelming increase in ROS during glutamate-mediated neurotoxicity can overwhelm intracellular redox mechanisms and lead to dysfunction and apoptosis of neurons. Interestingly, recent research is uncovering a link between ROS and Ca2+ that suggests ROS may act as second messengers that crosstalk with Ca2+ [for more on this topic refer to 26,92]. These findings strengthen the idea that uncontrolled glutamate-mediated Ca2+ influx upsets the intracellular redox homeostasis, lead to disruption of cellular processes and production of excess ROS. When expression of EAAT glutamate transporters is upregulated by administration of Ceftriaxone in mice exposed to hypoxia, they show less oxidative stress than control mice. This study confirmed glutamate-mediated calcium overload causing oxidative stress in the animals40. Therefore EAAT glutamate transporters indirectly function in redox homeostasis by maintaining glutamate homeostasis and preventing glutamate-induced oxidative stress and resulting neuronal death.

Redox Imbalance in Neurological Disease

Many diseases have been found to either cause or result from oxidative stress and altered glutathione levels. Some of these include atherosclerotic vascular, heart, liver, kidney, and neurological disease, among a host of others4,11. Multiple sclerosis, a chronic inflammatory disease of the CNS, has characteristic white matter lesions, which have been found to contain oxidized lipids and DNA, suggesting profound oxidative damage in oligodendrocytes93. Reduced glutathione levels and increasing GSSG/GSH ratios are seen in Wilson disease, a disorder in which copper aberrantly accumulates in different tissues, causing hepatotoxicity and neurological pathologies94.

Neurodegenerative disorders have been increasingly associated with redox imbalance and oxidative stress. Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Huntington’s are the most well studied disorders regarding pathology associated with loss of redox homeostasis4,11. Familial ALS was traced to a mutation in the Superoxide Dismutase (SOD-1) gene responsible for encoding the enzyme copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (SOD) 95,96. SOD is an important enzyme that catalyzes the neutralization of the superoxide anion (o2−) to prevent cellular damage. Additionally, one theory revolves around the interaction of ROS and Ca2+ signaling. A combination of oxidative stress and perturbed energy metabolism may compromise Ca2+-regulating mechanisms, leading to brain cell death12,97. In Parkinson’s disease, sustained intracellular calcium in dopaminergic neurons has been detected, which increases mitochondrial oxidant stress8. Increased ROS generation is detected in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, along with many other neural disorders, ultimately leading to brain cell dysfunction and death. For a more in depth review on oxidative stress’s role in neurodegenerative diseases see 11.

The Role of Glutamate Transporters and Glutathione in the Biology and Treatment of Glioma

Cancer is one of the most widely studied diseases in terms of oxidative stress, redox homeostasis, and glutathione. As rapidly dividing cells, they undergo continuous cellular metabolism and therefore produce higher than normal levels of ROS. Yet, they manage to flourish under these conditions. By altering the glutathione and redox systems in cells, they not only enhance their own survival, but detoxify our treatment interventions as well.

Clinically, we take advantage of exogenous ROS production for the treatment of cancer. Ionizing radiation is used to kill cancer cells by two mechanisms. The direct mechanism of cell death is achieved when ionizing radiation directly interacts with DNA, creating DNA damage and ultimately leading to cellular apoptosis. The most common mechanism of irradiation-induced cell death is through the indirect method, whereby radiation interacts with water molecules, which are abundant in cells, creating hydroxyl free radicals (OH•), that then interact with and damage DNA, causing cell death98.

Glutathione is an important player in cancer biology and treatment resistance. In fact, GSH is increased in many human cancers including breast, colon, pancreas, and brain, among many others99–104. Studies have found a link between increased GSH levels and chemotherapy and radiation resistance in many cancer types105,106 and it seems that cancer cells may respond to radiation therapy by increasing their production and utilization of GSH 107,108. Additionally, loss of GSH is thought to either allow or trigger the activation of the apoptotic cascade in cells, and there seems to be a correlation between GSH depletion and apoptosis in some cell types109–112. Cells with higher levels of GSH tend to have more resistance to apoptosis 113,114.

In glioma, or glial-derived primary brain tumors, as in other cancers, glutathione is an important survival mechanism. Glioma cells are dependent upon SXC-mediated cystine uptake for viability, as they require intracellular cystine/cysteine for GSH synthesis115,116. Removal of cystine from the medium, as well as inhibition of GSH synthesis with the γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase inhibitor buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) results in cell death. Similarly, treatment with Sulfasalazine to inhibit SXC depletes intracellular cystine and GSH, and inhibits glioma cell growth117,118. Additionally, as tumor cells outgrow their blood supply, areas of the tumor experience low oxygen tension, or hypoxia. Under hypoxic conditions, the dependence of glioma cells upon GSH increases, and they increase xCT cell-surface expression and SXC-mediated cystine uptake to meet this higher demand for GSH115,119. Expression of SLC7A11, the gene that encodes xCT, negatively correlates with chemotherapeutic resistance in glioma cells and inhibition of SXC activity or GSH synthesis increases sensitivity120,121.

Chemotherapy resistance in glioma is associated with elevated GSH levels122,123. GSH is able to bind xenobiotics, such as chemotherapy drugs, and export them out of cells through this family of proteins124. Expression of MRP1, one of the MRPs that mediate cellular export of GSH, is elevated in glioma125, and has also been found to be higher in higher-grade gliomas versus lower-grade gliomas126. Administration of Indomethacin, an MRP inhibitor, is able to increase the cytotoxic effect of etoposide in glioma cell lines125. The higher expression of these proteins may be at least one cause of multidrug resistance in human gliomas.

Radiation resistance in glioma also revolves around increased GSH. One study found that by depleting nuclear GSH before irradiation, nuclear fragmentation and apoptosis was increased127. A radioresistant clone of U251, a commonly used glioma cell line, has a 5-fold increase in antioxidant enzymes, including glutathione peroxidase and glutathione reductase. This resistant cell line showed cross-resistance to the commonly used chemotherapeutic cisplatin as well128. Similar findings are seen in other cancer cells. Sertoli cells demonstrate an increase in GSH after irradiation that is dose dependent108, and decreasing intracellular thiols in a lymphoma cell line increases radiation-induced apoptosis129. Even photodynamic therapy (PDT), which works in a similar manner to radiation therapy by producing ROS to kill cancer cells, is enhanced through GSH inhibition using BSO. PTD plus BSO enhances the ability of this treatment modality to kill tumor cells and decrease their migration130.

Taken together, much of the research today on cancer biology and therapy suggests GSH is an important therapeutic target. Many current treatment strategies are focused on GSH inhibition as a way to sensitize glioma and other cancer cells to current chemo- and radiotherapy [see 124 for an overview of some of these therapies]. Surprisingly however, little has been published regarding SXC inhibition in the context of sensitizing glioma cells to treatment. Recent studies have found that SXC inhibition using Sulfasalazine decreases chemotherapy and radiation resistance in pancreatic cancer103 and many in vitro and in vivo studies showing GSH dependence on SXC activity strongly suggest that SXC inhibition may be a viable mechanism to enhance current treatment of glioma116,117,131,132. In this study, we have investigated the consequences of SXC expression on radiation resistance in human derived glioma tissue. Using a xenograft model of glioma, where patient-derived glioblastoma tissue is propagated in the flank of nude mice, we were able to study tumors with high and low SXC expression and function. We found that high SXC expressing tumors are more radiation resistant than low SXC expressing tumors, and SXC inhibition with Sulfasalazine increases the sensitivity of high SXC expressing tumors. These results are presented and discussed in the following Results & Discussion section.

Methods

Drugs

All drugs were purchased from Sigma unless otherwise specified (St. Louis, MO). (S)-4-Carboxyphenylglycine was purchase from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO).

Xenografts

Xenografts were derived from primary brain tumors of patients and maintained by serial passage in mice, as previously described133. Flank tumor xenografts were harvested, mechanically disaggregated, and maintain in culture as ‘gliospheres’ in Neurobasal-A medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10mg/ml of EGF and FGF (Invitrogen), 250 μM/ml amphotericin, 50mg/ml gentamycin (Fisher), 260mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen), and 10 ml B-27 Supplement w/o Vitamin A (Invitrogen). Cells were used with in 2–3 weeks after harvesting from the animals.

Cell Culture

For experiments requiring a monolayer of cells, gliospheres were dissociated into single cell suspensions using accutase (Sigma) and plated using DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 7% fetal bovine serum and either 1% penicillin/streptomycin or 1% gentamycin (Fisher). Experiments were completed within 7 days of cells being plated.

Cell Proliferation

Proliferation was measured by seeding either 10,000 cells/well into each well of a 12-well plate, or 100,000 cells/well into each well of a 6-well plate. Cells were harvested using either 0.05% trypsin or accutase and re-suspended in 10 ml bath solution (125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1 CaCl2, 1.6 mM Na2HPO4, 0.4 NaH2PO4, 10.5 mM Glucose, and 32.5 mM HEPES acid). The pH was adjusted to 7.4 using NaOH and osmolarity was measured at ~300 mOsm. Cell number readings were made using a Coulter-Counter Cell Sizer (Beckman-Coulter, Miami, FL) and cell number was recorded per 500 μl. Mean cell number was normalized to either Day 0 or Day 4 control.

Western Blot

Radio-Immunoprecipitation Assay Buffer (RIPA) was used to lyse tissue as previously described115. Western blots were probed with the primary antibodies goat anti-xCT and CD98 (0.06 μg/ml, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), overnight at 4°C, and mouse anti-GAPDH (0.05 μg/ml, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) for 45 min at room temperature (RT). Blots were then washed in TBST 4 × 5 min and transferred to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) – conjugated secondary antibodies (2 μg/0.5 ml, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, Santa Cruz, CA) for 1 h at RT, followed by another wash (4 × 5 min in TBST. Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) was used to develop blots and the Kodak Image Station 4000MM (Kodak, New Haven, CT) was used to expose and image membranes.

3H-L-Glutamate Uptake

Glutamate uptake assays were performed as described previously131. Na+-independent uptake solution consisted of (in mM): 125.0 NaCl, 1.75 KCl, 1.25 mM KH2PO4, 23 triethylammounium (TEA) bicarbonate, 10 Glucose, 2.0 mM MgSO4, warmed to 37°C and bubbled with 5% CO2/20% O2 to maintain pH at 7.4. Cells were washed twice with uptake solution, then uptake solution containing 0.1 mM glutamate and 2 μCi 3H-glutamate (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Saint Louis, MO) was added for 3 minutes. Cells were washed twice with ice cold PBS to terminate uptake and lysed with 0.3 N NaOH for 30 min. 0.3 N HCl was then added to neutralize the solution. 3H activity was detected using a liquid scintillation counter (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA) and counts were normalized to protein contents, as measured using the Better Bradford Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL).

Glutathione Assay

Reduced glutathione was measured using the QuantiChrom™ Glutathione Assay Kit (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA). Manufacturer protocol was followed. Briefly, cells were collected and sonicated in a solution containing 50 mM NaH2PO4 and 1 mM EDTA. Lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4°C and the supernatant collected. Equal volumes of Reagent A was added to the supernatant, vortex, and centrifuged for 5 min at 14,000 rmp. 200 μl of sample/Reagent A mixture was aliquoted into wells of a 96-well plate and 100 μl of Reagent B was added to each well. After a 25 min incubation at RT, the samples were read at OD450nm. GSH concentration was calculated using the formula (ODsample − ODblank)/ODcalibrator − ODblank) × 100 × n = GSH (μM). GSH concentration was normalized to protein concentration, which was measured with the Bio-Rad DC protein assay kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA).

Radiation

Irradiation of cells was performed using an X-RAD 320 Irradiator (Precision X-ray Inc, North Branford, CT). The X-ray tube potential was set at 320 KV, and the mA was set at 12.50. Cells were irradiated at predetermined dose of Gy, as measured by a dosimeter. Cells were pretreated with drug for 1 h before irradiation, and fresh medium was added ± drug 24 h after irradiation.

Data Analysis

Data was graphed using Origin (v.8.5.1, MicroCal Software, North Hampton, MA) and analyzed using GraphPad InStat 3 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA Copyrigh 1992–1998 GraphPad Software, Inc.). A two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey post hoc test or unpaired t-test was use to determine significance, unless stated differently in the figure legend.

Results & Discussion

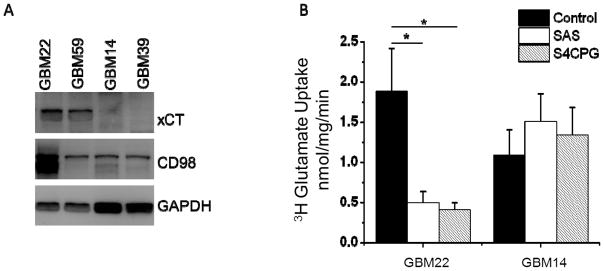

Protein analysis of commonly used cell lines (C6, D54-MG, U87, U251 and STTG1) reveals high expression of SXC79,131,134–136. Since protein expression can be altered over time in cell lines, we have adopted a xenograft model of glioma in which patient tissue is propagated in the flank of nude mice133. Using this model, we found that SXC expression in patient tumors is heterogeneous, and as a result we chose to functionally study tumors that express high and low levels of SXC. Figure 3A shows the xCT and CD98 expression of four of these ‘xenolines’, with two expressing high levels (GBM22 and GBM59) and two expressing low levels (GBM14 and GBM39) of the catalytic xCT subunit. We first tested functionality of SXC by performing radiolabeled 3[H]-glutamate uptake assays, a commonly used method of testing SXC function131. High SXC expressing GBM22 xenolines showed Na+-independent, Cl−-dependent uptake, which was inhibited with the SXC inhibitors Sulfasalazine (SAS) and (S)-4-Carboxyphenylglycine (S4CPG), confirming SXC-mediated uptake in high SXC expressing GBM22, but not in low SXC expressing GBM14 (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

A xenograft model of glioma, where human tissue is maintained in vivo, indicates heterogeneous expression of the two System xc− (SXC) subunits, xCT and CD98. A) Sample of four xenograft glioma tissues (labeled as GBM#) show two high and two low SXC expressing tumors. B) 3H-glutamate uptake assays indicate the high SXC expressing GBM22 tumor has Na+-independent, Sulfasalazine (SAS) and (S)-4-Carboxyphenylglycine (S4CPG) sensitive uptake, indicating SXC activity. Low SXC expressing tumors GBM14 have no measurable SXC activity. GBM14 and GBM22 were chosen as low and high SXC expressing tumors, respectively, for this study. (mean ± SEM; *p<0.05)

Glioma Cells Expressing High SXC Depend on L-Cystine and Glutathione for Growth

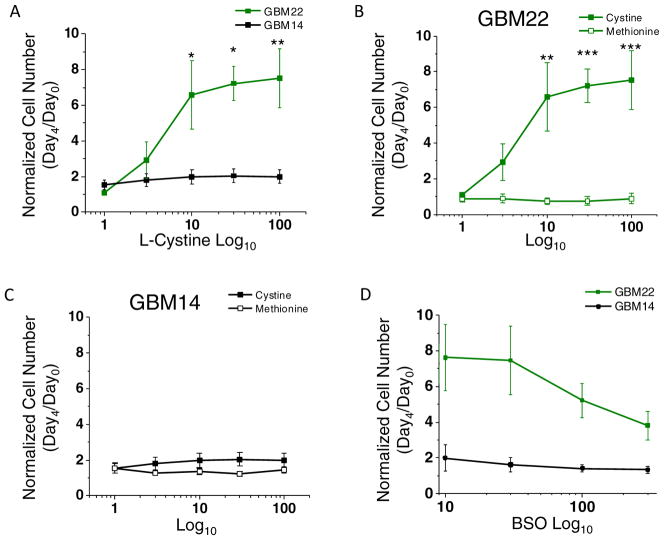

Previous studies have found that glioma cells rely on L-cystine for growth. Inhibition of SXC-mediated uptake results in cell death115,117. Glioma cell dependency on cystine uptake is due to their need to maintain intracellular GSH synthesis to detoxify ROS. Direct inhibition of GSH synthesis using buthionine sulfoximine (BSO), an inhibitor of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase, the enzyme mediating the rate-limiting reaction for GSH synthesis, significantly reduces glioma growth115. We therefore examined the growth dependency of GBM22 and GBM14 on L-cystine and GSH. Measuring cell number after four days of growth in the presence of increasing L-cystine concentration (0 – 100 μM) indicated that GBM22, but not GBM14, requires cystine for growth (Fig. 4A). At day 4, GBM22 showed a maximum increase of 7.52 ± 1.64 fold over control, versus 1.99 ± 0.38 for GBM14. The greatest increase in cell growth for GBM22 was reached with 10 μM L-cystine, which increased growth 6.58 ± 1.91 fold over day 0. In the absence of L-cystine, the growth of GBM22 cells was reduced to 0.83 ± 0.14 fold, which is significantly lower than at 10 μM L-cystine (p < 0.005) (Fig. 4A). Some cells are able to use a transsulfuration pathway to synthesize GSH from L-methionine in the absence of L-cystine137 and certain cancers are dependent exclusively on L-methionine availability for GSH synthesis and growth138. Therefore we also measured growth of these cells in the presence of increasing concentration (0 – 100 μM) of L-methionine. GBM22 cells showed no reliance upon this alternative GSH synthesis pathway, as their growth did not exceed 0.72 ± 0.11 fold from day 0 (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

High System xc− (SXC) expressing cells are more dependent upon cystine and glutathione (GSH) for growth. A) GBM22 cells, but not GBM14 cells, are dependent on L-cystine in the medium for growth. Significant increases in cell number occur at 10, 30, and 100 μM, with the greatest change in growth being at 10μM L-cystine. Low SXC GBM14 cells do not show the same dependence on L-cystine, with no change in cell number with added L-cystine. B–C) Neither GBM22 nor GBM14 cells rely upon methionine for growth. D) GSH synthesis inhibition using BSO decreases cell number of GBM22 cells, but not GBM14 cells, suggesting that GBM22 cells are much more reliant upon GSH for cell growth and survival. (mean ± SEM; **p<0.01, ***p<0.001).

These findings suggest that GBM14 cells behave differently than GBM22 cells. Overall, growth of GBM14 cells did not exceed ~2 fold under control conditions (Fig. 4A). Growth of cells in the presence of L-cystine or L-methionine at any concentration did not exceed 1.99 ± 0.38 and 1.44 ± 0.17 fold, respectively, which was not significant (Fig. 4C). To determine the dependence of these xenolines on GSH, GBM22 and GBM14 cells were treated with increasing concentrations (0 – 300 μM) of BSO for four days. Growth of GBM14 cells when treated with 300 μM BSO only decreased from 1.97 ± 0.67 to 1.33 ± 0.20 fold (Fig. 4D). However, the growth of GBM22 cells decreased from 7.28 ± 1.13 to 3.81 ± 0.80 fold, a difference which is significant when compared with a one-tailed paired t test (p = 0.0301) (two-tailed paired t test p = 0.0603).

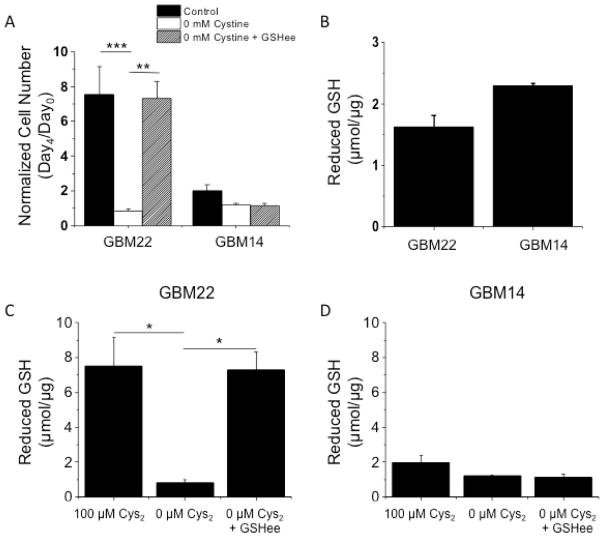

To directly determine the dependence of cell growth on GSH, glioma cells were treated with 100 μM L-cystine, 0 μM L-cystine, or 0 μM L-cystine + 5 mM GSH ethyl ester (GSHee) for four days. GSHee is a membrane permeable GSH-derivative that can supplement intracellular GSH. As in Figure 4A, 0 μM L-cystine decreased growth in GBM22 but not GBM14 xenolines. When GSHee was added to the medium, growth of GBM22 cells was restored, but had no effect on the growth of GBM14 cells (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

High SXC expressing cells depend on GSH for growth and require extracellular cystine for GSH synthesis. A) 0 mM cystine decreases GBM22 cell number almost 8-fold, and supplementing GSH ethyl ester, a membrane permeable GSH-derivative, restores cell growth. No significant change was seen in cell number for GBM14 with cystine (Cys2) depletion or GSHee supplementation. B) Reduced intracellular GSH concentrations are not significantly different between GBM22 and GBM14 at baseline, non-stressed conditions. C & D) GBM22 cells, but not GBM14 cells increase intracellular GSH concentrations when medium Cys2 are increased to 100 μM. GSH is depleted when Cys2 is removed from the medium, and rescued with GSHee supplementation, whereas GBM14 cell number remains unchanged. (mean ± SEM; **p<0.01, ***p<0.001).

To further investigate the differences in GSH dependence between GBM22 and GBM14 xenolines, we directly determined intracellular reduced GSH levels in the cells. Surprisingly, there was no difference in the basal levels of GSH between GBM14 (1.63 ± 0.18 μM/μg) and GBM22 (2.29 ± 0.04 μmol/μg) (Fig. 5B). However, when the cells were treated with 100 μM L-cystine, 0 μM L-cystine, or 0 μM L-cystine + 5 mM GSH ethyl ester (GSHee) for 24 hours, intracellular GSH in GBM22 changed dramatically, unlike GBM14 GSH concentrations. In the GBM22 cells, intracellular GSH levels decreased from 7.52 ± 1.64 μM/μg with 100 μM L-cystine, to 0.83 ± 0.14 μM/μg with 0 μM L-cystine. When GSHee was added however, intracellular GSH concentration was rescued (7.31 ± 1.00 μM/μg) (Fig. 5C). Intracellular GSH concentrations in GBM14 changed very little, and no rescue of GSH was seen with GSHee treatment (Fig. 5D). The changes in GSH follow the same trend as the changes in cell number in Figure 5A exposure to the same treatments.

High SXC Expressing Cells are more Resistant at Low Radiation Doses

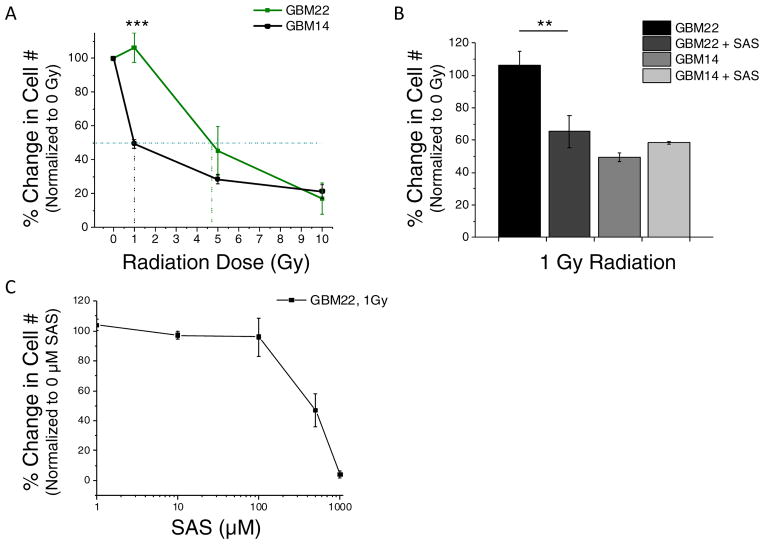

As a result of their ability to utilize extracellular cystine to increase intracellular GSH, we hypothesized that tumors with higher levels of SXC are inherently more radiation resistant than low SXC expressing tumors. To test this hypothesis, GBM22 and GBM14 cells were irradiated with 0, 1, 5, and 10 gray (Gy). Four days after irradiation, the cells were counted and percent survival was determined compared to day 4 control 0 Gy. GBM22 tumors were significantly more radiation resistant at 1 Gy, (p<0.001). Survival of GBM14 cells was decreased approximately 50% versus GBM22 cells, with percent survival being 49.5±2.6% and 106.4±8.5%, respectively (Fig. 6A). The LD50 radiation dose for GBM22 was ~5 Gy versus 1 Gy for GBM14, a 5x increase in the lethal dose required to kill 50% of the GBM22 tumor cells. At higher radiation doses, once 50% cell death occurred, the radiation resistance was eliminated for high SXC tumors. To test the effect of SXC inhibition on radiation resistance, we treated cells with 0.5 mM SAS before and after irradiation at 1 Gy. SAS + 1 Gy radiation decreased cell survival by approximately 50% [GBM22 % Survival at 1 Gy was 113.50±11.33 versus GBM22 + 0.5mM SAS at 1Gy was 65.32±9.81], showing an increase in sensitivity to SAS plus radiation, at low doses (Fig. 6B). Fig. 6C illustrates the dose response of GBM22 tumor cells to 1 – 1000 μM SAS at 1 Gy of radiation. SAS treatment did not alter GBM14 radiation sensitivity (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

System xc− (SXC) increases the resistance of glioma cells to low dose radiation. A) High SXC expressing GBM22 cells are >50% more resistant to 1 Gy radiation than low SXC expressing GBM14 cells. The LD50 (dotted horizontal bar) is 1 Gy for GBM14 cells versus 4.7 Gy for GBM22 cells, approximately a 5x higher lethal dose required for high SXC expressing cells. B) Inhibition of SXC using 0.5mM Sulfasalazine (SAS) did not affect the radiation response of GBM14 cells; however, it did decrease the percent of surviving cells exposed to 1 Gy. (mean ± SEM; **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). C) Dose response curve of GBM22 to 1 – 1000 μM SAS at 1 Gy.

Conclusions

High SXC expressing tumors exhibit a growth advantage over low SXC expressing tumors, as seen by the growth differences between the GBM22 and GBM14 xenolines. These findings are also replicated in vivo, as GBM22 xenolines that are implanted intracranially into mice kill the animals ~2x faster than implanted GBM14 tumors (unpublished data). This enhanced growth of high SXC expressing tumors is a result of their ability to utilize extracellular cystine for intracellular GSH synthesis. Our data suggests that high SXC expressing tumors are more radiation resistant, at least at lower radiation doses, due to their ability to increase their synthesis of GSH to neutralize the free radicals formed as a consequence of radiation exposure. SXC inhibition reduced the resistance of GBM22 cells to 1 Gy radiation, bringing their radiation sensitivity closer to that seen in the GBM14 cells. We found that the GBM14 cells grew much slower in culture than the GBM22 cells, which may be masking a difference in radiation sensitivity at higher doses. Since radiation more efficiently damages cells that are actively dividing, one could argue that the GBM14 cells are not being exposed to equivalent doses of radiation due to their slower growth. Treating these cells with a fractionated radiation dose schedule (ex. spreading a dose of 5 Gy over 5 days, administering 1 Gy/day), may uncover a greater separation of radiation sensitivity in these xenolines. Additionally, we hypothesize that at least under in vitro conditions, higher levels of radiation may cause cellular damage too quickly for GSH to neutralize and therefore these experiments should be repeated using an in vivo model to more accurately determine radiation dose and tumor resistance with and without SAS at higher doses.

Together, this data suggests that SXC is an important transporter for redox control in glioma cells and offers a growth and survival advantage to tumors that upregulate the expression of this transporter. Interestingly, it seems that low SXC expressing tumors may have alternative mechanisms that they rely upon to synthesize baseline GSH, as attested to by our finding that GBM14 cells have equivalent GSH concentrations to GBM22 under non-stressed, control conditions. However, these mechanisms do not appear to be as robust as SXC-mediate cystine uptake for GSH production, which may explain the sensitivity to radiation and decreased growth ability seen in the GBM14 xenolines. Other antioxidants such as superoxide dismutase and catalase may play a larger role in ROS detoxification in low SXC expressing tumors, since they are unable to increase their synthesis of GSH when greater antioxidant function is required. These findings are important especially for tumors expressing higher levels of SXC, as SAS may be a useful adjuvant to radiation therapy that may allow more effective therapy at lower radiation doses.

Highlights.

Redox homeostasis is important in the brain due to high O2 use and ROS production.

Glutathione is an important mediator of redox homeostasis in the brain.

System xc− and EAAT provide intracellular substrates for glutathione synthesis.

Gliomas cells with increased system xc− have a growth survival and advantage.

System xc− and glutathione may be important players in tumor treatment resistance.

Acknowledgments

The X-RAD 320 unit was purchased using a Research Facility Improvement Grant 1 G20RR022807-01, from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01NS052634, 2T32NS048039, and T32 GM008361.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Stephanie M. Robert, Email: srobe25@uab.edu.

Harald Sontheimer, Email: sontheimer@uab.edu.

References

- 1.Clarke DD, Sokoloff L. Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooker RJ, editor. Genetics: analysis and principles. McGraw-Hill Higher Education; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerlach M, Ben-Shachar D, Riederer P, Youdim MB. Altered brain metabolism of iron as a cause of neurodegenerative diseases? Journal of neurochemistry. 1994;63:793–807. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63030793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dringen R. Metabolism and functions of glutathione in brain. Progress in neurobiology. 2000;62:649–671. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porter NA. Chemistry of lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:273–282. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halliwell B. Reactive oxygen species and the central nervous system. Journal of neurochemistry. 1992;59:1609–1623. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb10990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho YS, et al. Mice deficient in cellular glutathione peroxidase develop normally and show no increased sensitivity to hyperoxia. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1997;272:16644–16651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surmeier DJ, Guzman JN, Sanchez-Padilla J, Goldberg JA. The origins of oxidant stress in Parkinson’s disease and therapeutic strategies. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2011;14:1289–1301. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalle-Donne I, et al. Molecular mechanisms and potential clinical significance of S-glutathionylation. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2008;10:445–473. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dringen R, Hirrlinger J. Glutathione pathways in the brain. Biological chemistry. 2003;384:505–516. doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uttara B, Singh AV, Zamboni P, Mahajan RT. Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative diseases: a review of upstream and downstream antioxidant therapeutic options. Current neuropharmacology. 2009;7:65–74. doi: 10.2174/157015909787602823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zundorf G, Reiser G. Calcium dysregulation and homeostasis of neural calcium in the molecular mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases provide multiple targets for neuroprotection. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2011;14:1275–1288. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richman PG, Meister A. Regulation of gamma-glutamyl-cysteine synthetase by nonallosteric feedback inhibition by glutathione. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1975;250:1422–1426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. The Biochemical journal. 2009;417:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen PK. Antimycin-insensitive oxidation of succinate and reduced nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide in electron-transport particles. I. pH dependency and hydrogen peroxide formation. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1966;122:157–166. doi: 10.1016/0926-6593(66)90057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickinson BC, Chang CJ. Chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species in signaling or stress responses. Nature chemical biology. 2011;7:504–511. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Why do cancers have high aerobic glycolysis? Nature reviews. Cancer. 2004;4:891–899. doi: 10.1038/nrc1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szatrowski TP, Nathan CF. Production of large amounts of hydrogen peroxide by human tumor cells. Cancer research. 1991;51:794–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hlavata L, Aguilaniu H, Pichova A, Nystrom T. The oncogenic RAS2(val19) mutation locks respiration, independently of PKA, in a mode prone to generate ROS. The EMBO journal. 2003;22:3337–3345. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carew JS, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in primary leukemia cells after chemotherapy: clinical significance and therapeutic implications. Leukemia. 2003;17:1437–1447. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussain SP, Hofseth LJ, Harris CC. Radical causes of cancer. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2003;3:276–285. doi: 10.1038/nrc1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sagara JI, Miura K, Bannai S. Maintenance of neuronal glutathione by glial cells. Journal of neurochemistry. 1993;61:1672–1676. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb09802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe H, Bannai S. Induction of cystine transport activity in mouse peritoneal macrophages. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1987;165:628–640. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.3.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deneke SM, Fanburg BL. Regulation of cellular glutathione. The American journal of physiology. 1989;257:L163–173. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1989.257.4.L163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pastore A, Federici G, Bertini E, Piemonte F. Analysis of glutathione: implication in redox and detoxification. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 2003;333:19–39. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(03)00200-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meister A, Anderson ME. Glutathione. Annual review of biochemistry. 1983;52:711–760. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van den Dobbelsteen DJ, et al. Rapid and specific efflux of reduced glutathione during apoptosis induced by anti-Fas/APO-1 antibody. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1996;271:15420–15427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghibelli L, et al. Rescue of cells from apoptosis by inhibition of active GSH extrusion. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 1998;12:479–486. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.6.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall AG. Review: The role of glutathione in the regulation of apoptosis. European journal of clinical investigation. 1999;29:238–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1999.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poot M, Teubert H, Rabinovitch PS, Kavanagh TJ. De novo synthesis of glutathione is required for both entry into and progression through the cell cycle. Journal of cellular physiology. 1995;163:555–560. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041630316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janaky R, et al. Glutathione and signal transduction in the mammalian CNS. Journal of neurochemistry. 1999;73:889–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paolicchi A, Dominici S, Pieri L, Maellaro E, Pompella A. Glutathione catabolism as a signaling mechanism. Biochemical pharmacology. 2002;64:1027–1035. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Misra I, Griffith OW. Expression and purification of human gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase. Protein expression and purification. 1998;13:268–276. doi: 10.1006/prep.1998.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chance B, Sies H, Boveris A. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:527–605. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper AJ, Kristal BS. Multiple roles of glutathione in the central nervous system. Biological chemistry. 1997;378:793–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pileblad E, Eriksson PS, Hansson E. The presence of glutathione in primary neuronal and astroglial cultures from rat cerebral cortex and brain stem. Journal of neural transmission. General section. 1991;86:43–49. doi: 10.1007/BF01250374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amara A, Coussemacq M, Geffard M. Antibodies to reduced glutathione. Brain research. 1994;659:237–242. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90885-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hjelle OP, Chaudhry FA, Ottersen OP. Antisera to glutathione: characterization and immunocytochemical application to the rat cerebellum. The European journal of neuroscience. 1994;6:793–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang H, et al. 12-Lipoxygenase plays a key role in cell death caused by glutathione depletion and arachidonic acid in rat oligodendrocytes. The European journal of neuroscience. 2004;20:2049–2058. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hota SK, Barhwal K, Ray K, Singh SB, Ilavazhagan G. Ceftriaxone rescues hippocampal neurons from excitotoxicity and enhances memory retrieval in chronic hypobaric hypoxia. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2008;89:522–532. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rice ME, Russo-Menna I. Differential compartmentalization of brain ascorbate and glutathione between neurons and glia. Neuroscience. 1998;82:1213–1223. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00347-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peuchen S, et al. Interrelationships between astrocyte function, oxidative stress and antioxidant status within the central nervous system. Progress in neurobiology. 1997;52:261–281. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Juurlink BH. Response of glial cells to ischemia: roles of reactive oxygen species and glutathione. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 1997;21:151–166. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson JX. Antioxidant defense of the brain: a role for astrocytes. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997;75:1149–1163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noble PG, Antel JP, Yong VW. Astrocytes and catalase prevent the toxicity of catecholamines to oligodendrocytes. Brain research. 1994;633:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91525-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hochman A, et al. Enhanced oxidative stress and altered antioxidants in brains of Bcl-2-deficient mice. Journal of neurochemistry. 1998;71:741–748. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71020741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Noel F, Tofilon PJ. Astrocytes protect against X-ray-induced neuronal toxicity in vitro. Neuroreport. 1998;9:1133–1137. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199804200-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Desagher S, Glowinski J, Premont J. Astrocytes protect neurons from hydrogen peroxide toxicity. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1996;16:2553–2562. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02553.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kranich O, Hamprecht B, Dringen R. Different preferences in the utilization of amino acids for glutathione synthesis in cultured neurons and astroglial cells derived from rat brain. Neuroscience letters. 1996;219:211–214. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(96)13217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dringen R, Hamprecht B. N-acetylcysteine, but not methionine or 2-oxothiazolidine-4-carboxylate, serves as cysteine donor for the synthesis of glutathione in cultured neurons derived from embryonal rat brain. Neuroscience letters. 1999;259:79–82. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00894-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dringen R, Pfeiffer B, Hamprecht B. Synthesis of the antioxidant glutathione in neurons: supply by astrocytes of CysGly as precursor for neuronal glutathione. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1999;19:562–569. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00562.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borst P, Evers R, Kool M, Wijnholds J. The multidrug resistance protein family. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1999;1461:347–357. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leslie EM, Deeley RG, Cole SP. Toxicological relevance of the multidrug resistance protein 1, MRP1 (ABCC1) and related transporters. Toxicology. 2001;167:3–23. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(01)00454-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paulusma CC, et al. Canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter/multidrug resistance protein 2 mediates low-affinity transport of reduced glutathione. The Biochemical journal. 1999;338 (Pt 2):393–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dringen R, Kranich O, Hamprecht B. The gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase inhibitor acivicin preserves glutathione released by astroglial cells in culture. Neurochemical research. 1997;22:727–733. doi: 10.1023/a:1027310328310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dringen R, Gutterer JM, Gros C, Hirrlinger J. Aminopeptidase N mediates the utilization of the GSH precursor CysGly by cultured neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2001;66:1003–1008. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McBean GJ. Cerebral cystine uptake: a tale of two transporters. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2002;23:299–302. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(02)02060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bannai S. Exchange of cystine and glutamate across plasma membrane of human fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:2256–2263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lo M, Wang YZ, Gout PW. The x(c)− cystine/glutamate antiporter: a potential target for therapy of cancer and other diseases. Journal of cellular physiology. 2008;215:593–602. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burdo J, Dargusch R, Schubert D. Distribution of the cystine/glutamate antiporter system xc− in the brain, kidney, and duodenum. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:549–557. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6840.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Piani D, Fontana A. Involvement of the cystine transport system xc− in the macrophage-induced glutamate-dependent cytotoxicity to neurons. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950) 1994;152:3578–3585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murphy TH, Schnaar RL, Coyle JT. Immature cortical neurons are uniquely sensitive to glutamate toxicity by inhibition of cystine uptake. FASEB J. 1990;4:1624–1633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shih AY, et al. Cystine/glutamate exchange modulates glutathione supply for neuroprotection from oxidative stress and cell proliferation. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2006;26:10514–10523. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3178-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vene R, et al. The cystine/cysteine cycle and GSH are independent and crucial antioxidant systems in malignant melanoma cells and represent druggable targets. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2011;15:2439–2453. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Banjac A, et al. The cystine/cysteine cycle: a redox cycle regulating susceptibility versus resistance to cell death. Oncogene. 2008;27:1618–1628. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Danbolt NC. Glutamate uptake. Progress in neurobiology. 2001;65:1–105. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lehre KP, Danbolt NC. The number of glutamate transporter subtype molecules at glutamatergic synapses: chemical and stereological quantification in young adult rat brain. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1998;18:8751–8757. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08751.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Furness DN, et al. A quantitative assessment of glutamate uptake into hippocampal synaptic terminals and astrocytes: new insights into a neuronal role for excitatory amino acid transporter 2 (EAAT2) Neuroscience. 2008;157:80–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Danbolt NC, Pines G, Kanner BI. Purification and reconstitution of the sodium- and potassium-coupled glutamate transport glycoprotein from rat brain. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6734–6740. doi: 10.1021/bi00480a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chaudhry FA, et al. Glutamate transporters in glial plasma membranes: highly differentiated localizations revealed by quantitative ultrastructural immunocytochemistry. Neuron. 1995;15:711–720. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rothstein JD, et al. Localization of neuronal and glial glutamate transporters. Neuron. 1994;13:713–725. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lewerenz J, Klein M, Methner A. Cooperative action of glutamate transporters and cystine/glutamate antiporter system Xc− protects from oxidative glutamate toxicity. Journal of neurochemistry. 2006;98:916–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zerangue N, Kavanaugh MP. Interaction of L-cysteine with a human excitatory amino acid transporter. The Journal of physiology. 1996;493 (Pt 2):419–423. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen Y, Swanson RA. The glutamate transporters EAAT2 and EAAT3 mediate cysteine uptake in cortical neuron cultures. Journal of neurochemistry. 2003;84:1332–1339. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aoyama K, Watabe M, Nakaki T. Modulation of neuronal glutathione synthesis by EAAC1 and its interacting protein GTRAP3-18. Amino acids. 2012;42:163–169. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0861-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aoyama K, et al. Neuronal glutathione deficiency and age-dependent neurodegeneration in the EAAC1 deficient mouse. Nature neuroscience. 2006;9:119–126. doi: 10.1038/nn1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cao L, Li L, Zuo Z. N-acetylcysteine reverses existing cognitive impairment and increased oxidative stress in glutamate transporter type 3 deficient mice. Neuroscience. 2012;220:85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pow DV. Visualising the activity of the cystine-glutamate antiporter in glial cells using antibodies to aminoadipic acid, a selectively transported substrate. Glia. 2001;34:27–38. doi: 10.1002/glia.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cho Y, Bannai S. Uptake of glutamate and cysteine in C-6 glioma cells and in cultured astrocytes. Journal of neurochemistry. 1990;55:2091–2097. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb05800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jang BG, et al. EAAC1 gene deletion alters zinc homeostasis and enhances cortical neuronal injury after transient cerebral ischemia in mice. Journal of trace elements in medicine and biology : organ of the Society for Minerals and Trace Elements (GMS) 2012;26:85–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sato H, Tamba M, Ishii T, Bannai S. Cloning and expression of a plasma membrane cystine/glutamate exchange transporter composed of two distinct proteins. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:11455–11458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.de Groot J, Sontheimer H. Glutamate and the biology of gliomas. Glia. 2011;59:1181–1189. doi: 10.1002/glia.21113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bergles DE, Jahr CE. Synaptic activation of glutamate transporters in hippocampal astrocytes. Neuron. 1997;19:1297–1308. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chaudhry FA, Reimer RJ, Edwards RH. The glutamine commute: take the N line and transfer to the A. The Journal of cell biology. 2002;157:349–355. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200201070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Benjamin AM, Quastel JH. Metabolism of amino acids and ammonia in rat brain cortex slices in vitro: a possible role of ammonia in brain function. Journal of neurochemistry. 1975;25:197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1975.tb06953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Martinez-Hernandez A, Bell KP, Norenberg MD. Glutamine synthetase: glial localization in brain. Science. 1977;195:1356–1358. doi: 10.1126/science.14400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kvamme E, Torgner IA, Roberg B. Kinetics and localization of brain phosphate activated glutaminase. J Neurosci Res. 2001;66:951–958. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Svenneby G. Pig brain glutaminase: purification and identification of different enzyme forms. Journal of neurochemistry. 1970;17:1591–1599. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1970.tb03729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hidalgo C, Carrasco MA. Redox control of brain calcium in health and disease. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2011;14:1203–1207. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Atlante A, et al. Glutamate neurotoxicity, oxidative stress and mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 2001;497:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dykens JA, Stern A, Trenkner E. Mechanism of kainate toxicity to cerebellar neurons in vitro is analogous to reperfusion tissue injury. Journal of neurochemistry. 1987;49:1222–1228. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb10014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hidalgo C, Donoso P. Crosstalk between calcium and redox signaling: from molecular mechanisms to health implications. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2008;10:1275–1312. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Haider L, et al. Oxidative damage in multiple sclerosis lesions. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2011;134:1914–1924. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sauer SW, et al. Severe dysfunction of respiratory chain and cholesterol metabolism in Atp7b(−/−) mice as a model for Wilson disease. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2011;1812:1607–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Orrell RW, et al. Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with a point mutation of SOD-1: intrafamilial heterogeneity of disease duration associated with neurofibrillary tangles. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1995;59:266–270. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.59.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rosen DR, et al. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 1993;362:59–62. doi: 10.1038/362059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gleichmann M, Mattson MP. Neuronal calcium homeostasis and dysregulation. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2011;14:1261–1273. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cadet J, et al. Radiation-induced DNA damage: formation, measurement, and biochemical features. Journal of environmental pathology, toxicology and oncology : official organ of the International Society for Environmental Toxicology and Cancer. 2004;23:33–43. doi: 10.1615/jenvpathtoxoncol.v23.i1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yeh CC, et al. A study of glutathione status in the blood and tissues of patients with breast cancer. Cell biochemistry and function. 2006;24:555–559. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Suess E, et al. Technetium-99m-d,1-hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime (HMPAO) uptake and glutathione content in brain tumors. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 1991;32:1675–1681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schnelldorfer T, et al. Glutathione depletion causes cell growth inhibition and enhanced apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer. 2000;89:1440–1447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Grubben MJ, van den Braak CC, Nagengast FM, Peters WH. Low colonic glutathione detoxification capacity in patients at risk for colon cancer. European journal of clinical investigation. 2006;36:188–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lo M, Ling V, Wang YZ, Gout PW. The xc− cystine/glutamate antiporter: a mediator of pancreatic cancer growth with a role in drug resistance. British journal of cancer. 2008;99:464–472. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Louw DF, Bose R, Sima AA, Sutherland GR. Evidence for a high free radical state in low-grade astrocytomas. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:1146–1150. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199711000-00025. discussion 1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Britten RA, Green JA, Warenius HM. Cellular glutathione (GSH) and glutathione S-transferase (GST) activity in human ovarian tumor biopsies following exposure to alkylating agents. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 1992;24:527–531. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)91069-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bracht K, Boubakari, Grunert R, Bednarski PJ. Correlations between the activities of 19 anti-tumor agents and the intracellular glutathione concentrations in a panel of 14 human cancer cell lines: comparisons with the National Cancer Institute data. Anti-cancer drugs. 2006;17:41–51. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000190280.60005.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kuppusamy P, et al. Noninvasive imaging of tumor redox status and its modification by tissue glutathione levels. Cancer research. 2002;62:307–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Brouazin-Jousseaume V, Guitton N, Legue F, Chenal C. GSH level and IL-6 production increased in Sertoli cells and astrocytes after gamma irradiation. Anticancer research. 2002;22:257–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kern JC, Kehrer JP. Free radicals and apoptosis: relationships with glutathione, thioredoxin, and the BCL family of proteins. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library. 2005;10:1727–1738. doi: 10.2741/1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Franco R, Cidlowski JA. SLCO/OATP-like transport of glutathione in FasL-induced apoptosis: glutathione efflux is coupled to an organic anion exchange and is necessary for the progression of the execution phase of apoptosis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:29542–29557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602500200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hammond CL, Marchan R, Krance SM, Ballatori N. Glutathione export during apoptosis requires functional multidrug resistance-associated proteins. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:14337–14347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Armstrong JS, Jones DP. Glutathione depletion enforces the mitochondrial permeability transition and causes cell death in Bcl-2 overexpressing HL60 cells. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2002;16:1263–1265. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0097fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Cazanave S, et al. High hepatic glutathione stores alleviate Fas-induced apoptosis in mice. Journal of hepatology. 2007;46:858–868. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Friesen C, Kiess Y, Debatin KM. A critical role of glutathione in determining apoptosis sensitivity and resistance in leukemia cells. Cell death and differentiation. 2004;11 (Suppl 1):S73–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ogunrinu TA, Sontheimer H. Hypoxia increases the dependence of glioma cells on glutathione. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:37716–37724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.161190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sontheimer H. A role for glutamate in growth and invasion of primary brain tumors. Journal of neurochemistry. 2008;105:287–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chung WJ, et al. Inhibition of cystine uptake disrupts the growth of primary brain tumors. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25:7101–7110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5258-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chung WJ, Sontheimer H. Sulfasalazine inhibits the growth of primary brain tumors independent of nuclear factor-kappaB. Journal of neurochemistry. 2009;110:182–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Scatena R. Mitochondria and cancer: a growing role in apoptosis, cancer cell metabolism and dedifferentiation. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2012;942:287–308. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-2869-1_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Guan J, et al. The xc− cystine/glutamate antiporter as a potential therapeutic target for small-cell lung cancer: use of sulfasalazine. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2009;64:463–472. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0894-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Huang Y, Dai Z, Barbacioru C, Sadee W. Cystine-glutamate transporter SLC7A11 in cancer chemosensitivity and chemoresistance. Cancer research. 2005;65:7446–7454. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ali-Osman F, Stein DE, Renwick A. Glutathione content and glutathione-S-transferase expression in 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea-resistant human malignant astrocytoma cell lines. Cancer research. 1990;50:6976–6980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Friedman HS, et al. Cyclophosphamide resistance in medulloblastoma. Cancer research. 1992;52:5373–5378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Singh S, Khan AR, Gupta AK. Role of glutathione in cancer pathophysiology and therapeutic interventions. Journal of experimental therapeutics & oncology. 2012;9:303–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Benyahia B, et al. Multidrug resistance-associated protein MRP1 expression in human gliomas: chemosensitization to vincristine and etoposide by indomethacin in human glioma cell lines overexpressing MRP1. J Neurooncol. 2004;66:65–70. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000013484.73208.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.de Faria GP, et al. Differences in the expression pattern of P-glycoprotein and MRP1 in low-grade and high-grade gliomas. Cancer investigation. 2008;26:883–889. doi: 10.1080/07357900801975264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Morales A, Miranda M, Sanchez-Reyes A, Biete A, Fernandez-Checa JC. Oxidative damage of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA induced by ionizing radiation in human hepatoblastoma cells. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 1998;42:191–203. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lee HC, et al. Increased expression of antioxidant enzymes in radioresistant variant from U251 human glioblastoma cell line. International journal of molecular medicine. 2004;13:883–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Mirkovic N, et al. Resistance to radiation-induced apoptosis in Bcl-2-expressing cells is reversed by depleting cellular thiols. Oncogene. 1997;15:1461–1470. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Jiang F, et al. Photodynamic therapy with photofrin in combination with Buthionine Sulfoximine (BSO) of human glioma in the nude rat. Lasers in medical science. 2003;18:128–133. doi: 10.1007/s10103-003-0269-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ye ZC, Rothstein JD, Sontheimer H. Compromised glutamate transport in human glioma cells: reduction-mislocalization of sodium-dependent glutamate transporters and enhanced activity of cystine-glutamate exchange. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1999;19:10767–10777. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-24-10767.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sato H, et al. Redox imbalance in cystine/glutamate transporter-deficient mice. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:37423–37429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506439200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Giannini C, et al. Patient tumor EGFR and PDGFRA gene amplifications retained in an invasive intracranial xenograft model of glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro-oncology. 2005;7:164–176. doi: 10.1215/S1152851704000821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.de Groot JF, Liu TJ, Fuller G, Yung WK. The excitatory amino acid transporter-2 induces apoptosis and decreases glioma growth in vitro and in vivo. Cancer research. 2005;65:1934–1940. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]