Abstract

Virus and host gene phylogenies, indicating that antigenically distinct hantaviruses (family Bunyaviridae, genus Hantavirus) segregate into clades, which parallel the molecular evolution of rodents belonging to the Murinae, Arvicolinae, Neotominae and Sigmodontinae subfamilies, suggested co-divergence of hantaviruses and their rodent reservoirs. Lately, this concept has been vigorously contested in favor of preferential host switching and local host-specific adaptation. To gain insights into the host range, spatial and temporal distribution, genetic diversity and evolutionary origins of hantaviruses, we employed reverse transcription- polymerase chain reaction to analyze frozen, RNAlater®-preserved and ethanol-fixed tissues from 1,546 shrews (9 genera, 47 species), 281 moles (8 genera, 10 species) and 520 bats (26 genera and 53 species), collected in Europe, Asia, Africa and North America during 1980–2012. Thus far, we have identified 24 novel hantaviruses in shrews, moles and bats. That these newfound hantaviruses are geographically widespread and genetically more diverse than those harbored by rodents suggests that the evolutionary history of hantaviruses is far more complex than previously conjectured. Phylogenetic analyses indicate four distinct clades, with the most divergent comprising hantaviruses harbored by the European mole and insectivorous bats, with evidence for both co-divergence and host switching. Future studies will provide new knowledge about the transmission dynamics and pathogenic potential of these newly discovered, still-orphan, non-rodent-borne hantaviruses.

Keywords: Hantavirus, Soricomorpha, Chiroptera, Evolution

Introduction

More than a decade before the seminal milestone demonstrating that Hantaan virus (HTNV) in the striped field mouse (Apodemus agrarius) was the prototype virus of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) (Lee et al., 1978), Thottapalayam virus (TPMV) was isolated from an Asian house shrew (Suncus murinus) captured in southern India in 1964 (Carey et al., 1971). But even after this formerly unclassified virus was shown to be a hantavirus (Zeller et al., 1989), the prevailing assumption was that TPMV represented a spillover event from a rodent host. Also, despite decades-old reports of HFRS antigens or antibodies in the Eurasian common shrew (Sorex araneus), Eurasian pygmy shrew (Sorex minutus), Eurasian water shrew (Neomys fodiens), European mole (Talpa europaea), Chinese mole shrew (Anourosorex squamipes) and northern short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda) (Chen et al., 1986; Gavrilovskaya et al., 1983; Gligic et al., 1992; Lee et al., 1985a; Tkachenko et al., 1983), shrews and moles (order Soricomorpha, family Soricidae and Talpidae) had been largely ignored in the ecology and evolution of hantaviruses (family Bunyaviridae, genus Hantavirus). However, earlier serological tests and recent whole genome sequence analysis of TPMV, showing that it occupies an entirely separate evolutionary lineage, support an early divergence from rodent-borne hantaviruses (Chu et al., 1994; Song et al., 2007a; Xiao et al., 1994; Yadav et al., 2007).

Subsequent acquisition of new knowledge about the spatial and temporal distribution, host range and genetic diversity of hantaviruses in shrews and moles, and later in bats (order Chiroptera), was made possible largely through the generosity of museum curators and field mammalogists who willingly granted access to their archival tissue collections. The availability of such specimens provides strong justification for the continued expansion and long-term maintenance of archival tissue repositories for future investigations.

Phylogenetic analyses of these newfound hantaviruses indicate at least four distinct clades, with the most divergent lineage comprising hantaviruses harbored by the European mole (Kang et al., 2009c) and insectivorous bats (Arai et al., 2013; Guo et al., 2013; Sumibcay et al., 2012; Weiss et al., 2012). The realization that these soricomorph- and chiropteran-borne hantaviruses are genetically more diverse than those found in rodents suggests that the evolutionary history of hantaviruses is far more complex than previously conjectured. Thus, a new era in hantavirology is now focused on exploring the ‘inconvenient’ evidence that rodents may not be the original mammalian hosts of primordial hantaviruses. Also, the once-growing complacency and indifference toward rodent-borne hantaviruses is being supplanted by renewed zeal to fill major gaps in our understanding about the ecology, transmission dynamics and pathogenic potential of these newly discovered, still-orphan hantaviruses, before the next new disease outbreak is documented.

The history of hantaviruses has been marked by rediscovery and new beginnings. In this short review, the genetic diversity and phylogeography of hantaviruses from non-rodent small mammals are summarized in an attempt to gain insights into their evolutionary origins.

Hantavirus Hunting

To gain insights into the host diversity of hantaviruses, we analyzed archival tissues from 1,546 shrews (representing 9 genera and 47 species), 281 moles (8 genera and 10 species) and 520 bats (26 genera and 53 species), captured in Europe, Asia, Africa and North America during a more than three decade period, 1980–2012, using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Ironically, the availability of the TPMV whole genome was unhelpful, because of the rich genetic diversity of soricomorph- and chiroptera-borne hantaviruses. That is, for nearly every new hantavirus, time-consuming and labor-intensive hit-and-miss efforts of designing and redesigning oligonucleotide primers were necessary. This brute-force approach was rewarded by the identification of genetically distinct hantaviruses (likely representing new viral species) in multiple species of shrews belonging to three subfamilies (Soricinae, Crocidurinae and Myosoricinae) and moles of two subfamilies (Talpinae and Scalopinae) captured in widely separated geographic regions (Arai et al., 2007, 2008a, 2008b, 2012; Gu et al., 2011, 2013a, 2013b, 2013c; Kang et al., 2009a, 2009b, 2009c, 2010c, 2011a, 2011b, 2011c; Song et al., 2007b, 2007c, 2009; Yashina et al., 2010).

Additional shrew-borne hantaviruses, including Asikkala virus in the Eurasian pygmy shrew (Sorex minutus) (Radosa et al., 2013), Tanganya virus in the Therese’s shrew (Crocidura theresae) (Klempa et al., 2007) and Yakeshi virus in the taiga shrew (Sorex isodon) (Guo et al., 2013), and genetic variants of Seewis virus (SWSV) have been reported by other investigators (Resman et al., 2013; Schlegel et al., 2012b). And recently, the host range of hantaviruses has been further expanded by the detection of highly divergent hantavirus lineages in insectivorous bats (order Chiroptera) from Côte d’Ivoire (Sumibcay et al., 2012), Sierra Leone (Weiss et al., 2012), Vietnam (Arai et al., 2013) and China (Guo et al., 2013). As shown in Figure 1, the emerging global landscape of hantaviruses, with the addition of soricid-, talpid- and chiropteran-borne hantaviruses against a backdrop of representative hantaviruses harbored by rodents, has become almost unrecognizable from just a few years ago.

Figure 1.

Global landscape of representative rodent-borne hantaviruses and newfound hantaviruses harbored by shrews, moles and insectivorous bats. Lines indicate the approximate geographic locations where reservoir hosts were captured.

Initially, our search for hantaviruses was limited to frozen tissues, in the belief that the probability of success would be highest. However, this self-imposed restriction reduced our virus-discovery opportunities, so we expanded the testing to include tissues preserved in RNAlater® RNA Stabilization Reagent with good success. More recently, because maintaining a cold chain under field conditions is not always feasible, we have found that archival tissues fixed in 90% ethanol are also suitable, as evidenced by the identification of a highly divergent hantavirus in ethanol-fixed liver tissue from banana pipistrelles (Neoromicia nanus) captured in Côte d’Ivoire (Sumibcay et al., 2012) and the full-length genome analysis of a hantavirus amplified from ethanol-fixed intercostal muscle of a Doucet’s musk shrew (Crocidura douceti) from Guinea (Gu et al., 2013c). Thus, ethanol-fixed tissues, originally collected for other purposes, should greatly expand the pool of specimens for hantavirus hunting, particularly tissues from other insectivorous small mammals, such as hedgehogs (order Erinaceomorpha) and tenrecs (order Afrosoricida).

Tables 1, 2 and 3 list 32 hantaviruses identified to date in shrews, moles and bats, respectively. Among the more salient observations is the marked preponderance of 15 genetically distinct hantaviruses in soricomorphs and chiropterans from Asia, compared to the comparatively lower number of four from Europe, seven from Africa and six from North America. Notable also are the five hantaviruses detected in African shrews, compared to only two reported from African rodents (Klempa et al., 2006; Meheretu et al., 2012), despite the testing of tissues from many more rodents than shrews, suggesting that rodents may not have been the primordial mammalian hosts of ancestral hantaviruses. Moreover, the far greater genetic diversity of hantaviruses hosted by Asian soricomorphs and chiropterans and their basal positions in phylogenetic trees suggest that hantaviruses originated in Asia (Bennett et al., 2014; Kang et al., 2011b). An Asian origin was similarly concluded following an analysis of 190 S-segment sequences of rodent-borne hantaviruses, found in 30 countries during 1985 to 2010, retrieved from GenBank (Souza et al., 2013).

Table 1.

Hantaviruses detected in shrews (order Soricomorpha, family Soricidae).

| Virus Name | Reservoir Host | Country | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thottapalayam | Suncus murinus | India | 1964 | Carey 1971 |

| Bowé | Crocidura douceti | Guinea | 2012 | Gu 2013c |

| Imjin | Crocidura lasiura | Korea | 2004 | Song 2009 |

| Azagny | Crocidura obscurior | Côte d’Ivoire | 2009 | Kang 2011b |

| Jeju | Crocidura shantungensis | Korea | 2007 | Arai 2012 |

| Tanganya | Crocidura theresae | Guinea | 2004 | Klempa 2007 |

| Uluguru | Myosorex geata | Tanzania | 1996 | Unpublished |

| Kilimanjaro | Myosorex zinki | Tanzania | 2002 | Unpublished |

| Cao Bang | Anourosorex squamipes | Vietnam | 2006 | Song 2007c |

| Xinyi | Anourosorex yamashinai | Taiwan | 1989 | Unpublished |

| Camp Ripley | Blarina brevicauda | United States | 1998 | Arai 2007 |

| Iamonia | Blarina carolinensis | United States | 1983 | Unpublished |

| Boginia | Neomys fodiens | Poland | 2011 | Gu 2013b |

| Seewis | Sorex araneus | Switzerland | 2006 | Song 2007b |

| Amga | Sorex caecutiens | Russia | 2006 | Unpublished |

| Ash River | Sorex cinereus | United States | 1994 | Arai 2008a |

| Qiandao Lake | Sorex cylindricauda | China | 2005 | Unpublished |

| Yakeshi | Sorex isodon | China | 2006 | Guo 2013 |

| Asikkala | Sorex minutus | Czech Republic | 2010 | Radosa 2013 |

| Jemez Springs | Sorex monticolus | United States | 1996 | Arai 2008a |

| Kenkeme | Sorex roboratus | Russia | 2006 | Kang 2010 |

| Sarufutsu | Sorex unguiculatus | Japan | 2006 | Unpublished |

Table 2.

Hantaviruses detected in moles (order Soricomorpha, family Talpidae).

| Virus Name | Reservoir Host | Country | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asama | Urotrichus talpoides | Japan | 2008 | Arai 2008b |

| Dahonggou Creek | Scaptonyx fusicaudus | China | 1989 | Unpublished |

| Nova | Talpa europaea | Hungary | 1999 | Kang 2009b |

| Oxbow | Neurotrichus gibbsii | United States | 2003 | Kang 2009a |

| Rockport | Scalopus aquaticus | United States | 1986 | Kang 2011a |

Table 3.

Hantaviruses detected in insectivorous bats (order Chiroptera).

| Virus Name | Reservoir Host | Country | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huangpi | Pipistrellus abramus | China | 2011 | Guo 2013 |

| Longquan* | Rhinolophus sinicus | China | 2011 | Guo 2013 |

| Magboi | Nycteris hispida | Sierra Leone | 2010 | Weiss 2012 |

| Mouyassué | Neoromicia nanus | Côte d’Ivoire | 2011 | Sumibcay 2012 |

| Xuan Son | Hipposideros pomona | Vietnam | 2012 | Arai 2013 |

Longquan virus was also found in Rhinolophus affinis and Rhinolophus monoceros.

Soricid-borne Hantaviruses

Of the 47 shrew species we tested, hantavirus RNA was found in 27 species. However, genetically distinct hantaviruses numbered only 18, using the criteria of greater than 10% and 12% amino acid sequence difference for the S- and M-segment gene products, respectively (Maes et al., 2009). Because the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses has not adopted this latter definition, only TPMV is a recognized novel hantavirus species harbored by a shrew host for the time being. Nevertheless, evidence of host sharing was found in nine shrew species. SWSV, which was first detected in a single Eurasian common shrew captured in Switzerland (Song et al., 2007b) and subsequently in common shrews from Austria, Czech Republic, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Russia and Slovenia (Gu et al., 2013b; Kang et al., 2009; Resman et al., 2013; Schlegel et al., 2012b; Yashina et al., 2011), has also been found in the Siberian large-toothed shrew (Sorex daphaenodon), Eurasian pygmy shrew (Sorex minutus), tundra shrew (Sorex tundrensis) and Mediterranean water shrew (Neomys anomalus). Similarly, Jemez Springs virus (JMSV), hosted by the dusky shrew (Sorex monticolus) (Arai et al., 2008a), has also been detected in the Baird’s shrew (Sorex bairdi), prairie shrew (Sorex haydeni), American water shrew (Sorex palustris), Trowbridge’s shrew (Sorex trowbridgii) and vagrant shrew (Sorex vagrans) in North America (H.J. Kang and R. Yanagihara, unpublished observations).

More than prototype TPMV, Imjin virus (MJNV), isolated recently from Ussuri white-toothed shrews (Crocidura lasiura) captured near the demilitarized zone in the Republic of Korea, is possibly the best characterized soricid-borne hantavirus identified to date (Song et al., 2009). High prevalence of MJNV infection has been recorded, particularly within discrete foci during the autumn, with evidence of marked male predominance. By applying plaque-reduction neutralization tests, which have been used to classify hantavirus isolates (Chu et al., 1994; Lee et al., 1985b; Xiao et al., 1994), a one-way cross neutralization was detected between MJNV and TPMV, while with no cross neutralization was found with rodent-borne hantaviruses.

Talpid-borne Hantaviruses

Of the more than 40 extant mole species, tissues from 10 species were tested, yielding five genetically distinct hantaviruses (Arai et al., 2008b; Kang et al., 2009b, 2009c, 2011a). Undoubtedly, this represents a gross underestimation of the number of talpid-borne hantaviruses, because many more mole species were unavailable for testing and for the 10 species tested, the sample sizes were small (Table 4). More targeted searches for hantavirus RNA in mole species that share common ancestries with the known talpid reservoirs will likely lead to the discovery of additional hantaviruses and/or clarify whether or not host sharing occurs among moles. In addition, studies of syntopic shrews and rodents are warranted to ascertain host-switching events. In this regard, especially noteworthy is the broad phylogenetic positions occupied by talpid-borne hantaviruses. As shown in Figure 2, mole-borne hantaviruses have been found in each of the four hantavirus clades. That these hantaviruses are somewhat more catholic in their host proclivity than present-day rodent-borne hantaviruses suggests that ancestral moles may have served as the early hosts of primordial hantaviruses.

Table 4.

Search for hantavirus RNA in archival tissues from moles (order Soricomorpha, family Talpidae).

| Genus species | USA | Hungary | Poland | France | England | Japan | Vietnam | China | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euroscaptor longirostris | 0/12 | 0/12 | |||||||

| Neurotrichus gibbsii | 1/10 | 1/10 | |||||||

| Scalopus aquaticus | 4/60 | 4/60 | |||||||

| Scapanus latimanus | 0/4 | 0/4 | |||||||

| Scapanus townsendii | 0/2 | 0/2 | |||||||

| Scapanus orarius | 0/3 | 0/3 | |||||||

| Scaptonyx fusicaudus | 1/2 | 1/2 | |||||||

| Talpa europaea | 1/6 | 18/35 | 61/94 | 0/4 | 80/139 | ||||

| Uropsilus soricipes | 0/5 | 0/5 | |||||||

| Urotrichus talpoides | 6/44 | 6/44 | |||||||

| Total | 5/79 | 1/6 | 18/35 | 61/94 | 0/4 | 6/44 | 0/12 | 1/7 | 92/281 |

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree generated by MrBayes, using the GTR+I+Γ model of evolution, based on a 1,058-nucleotide region of the L segment of mole-, shrew- and rodent-borne hantaviruses. The phylogenetic positions of five talpid-borne hantaviruses, including Nova virus (NVA MSB95703: FJ593498), Dahonggou Creek virus (DHC DGR36708: HQ616595), Oxbow virus (OXB Ng1453: FJ593497), Asama virus (ASA N10: EU929078) and Rockport virus (RKP MSB57412: HM015221), are shown (red boxes) in relationship with hantaviruses harbored by rodents and shrews.

One of the most highly divergent lineages of hantaviruses is represented by Nova virus (NVAV), originally detected in archival liver tissue from a single European mole (Talpa europaea), captured in Zala County, Hungary, in July 1999 (Kang et al., 2009c). As evidenced by RT-PCR and confirmed by DNA sequencing, recent studies indicate prevalences of NVAV infection exceeding 50% in European moles from France and Poland, suggesting efficient enzootic virus transmission and a well-established, long-standing reservoir host-hantavirus relationship (Gu et al., 2013a; S.H. Gu and J. Markowski, unpublished observations). It is likely that NVAV occurs throughout the vast distribution of the European mole, much like SWSV is widespread in the Eurasian common shrew throughout Europe. The rodent homologues are Puumala virus (PUUV) in the bank vole (Myodes glareolus) in Europe and Sin Nombre virus (SNV) in the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) in North America.

Chiropteran-borne Hantaviruses

Despite the more than 1,500 tissue samples we and others have tested from approximately 100 species of insectivorous bats, only five hantaviruses have hitherto been found: Mouyassué virus in the banana pipistrelle from Côte d’Ivoire (Sumibcay et al., 2012), Magboi virus in the hairy slit-faced bat (Nycteris hispida) from Sierra Leone (Weiss et al., 2012), Xuan Son virus in the Pomona roundleaf bat (Hipposideros pomona) from Vietnam (Arai et al., 2013), and Hunagpi virus in the Japanese house bat (Pipistrellus abramus) and Longquan virus in the Chinese horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus sinicus), Formosan lesser horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus monoceros) and intermediate horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus affinis) from China (Guo et al., 2013).

Although hantavirus RNA has not been detected in fruit bats (or flying foxes), bat species hosting hantaviruses curiously belong to both suborders of bats, namely the Yinpterochiroptera (Pteropodiformes), which include the families Hipposideridae (Old World leaf-nosed bats) and Rhinolophidae (horseshoe bats), as well as the family Pteropodidae (megabats), and the Yangochiroptera (Vespertilioniformes), which include the families Nycteridae (hollow-faced bats) and Vespertilionidae (vesper bats) (Figure 3). Again, representation in both suborders would suggest that primordial hantaviruses may have infected an early common ancestor of bats.

Figure 3.

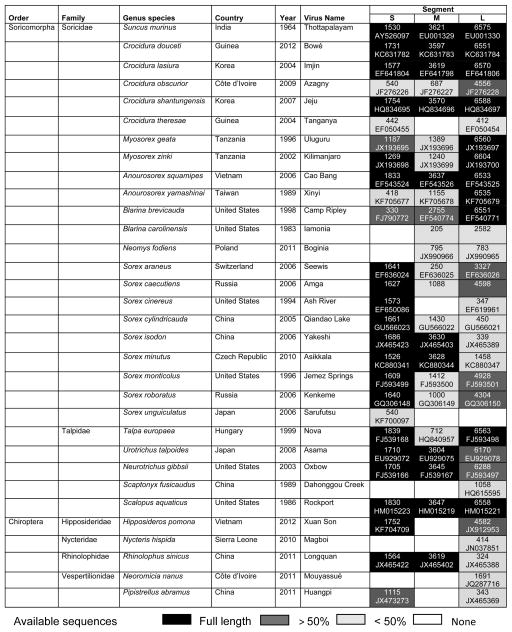

Summary of available sequences for 32 soricomorph- and chiroptera-borne hantaviruses. Of these, full-length S-segment sequences are completed for 20. None of the bat-borne hantaviruses have been fully sequenced, and specifically no full-length L-segment sequences are available. The number of nucleotides for each segment is shown for each non-rodent-borne hantavirus with the GenBank number, when available.

The low success rate of detecting hantavirus RNA in bat tissues, compared to the much higher success rates for similar efforts in soricomorphs, may be attributed to the highly divergent nature of their genomes, as well as the very focal nature of hantavirus infection, small sample sizes from any given bat species, primer mismatches, and suboptimal PCR cycling conditions (Arai et al., 2013). On the other hand, while fewer bat species might serve as reservoirs, the hantaviruses they harbor are among the most genetically diverse described to date.

Hantavirus Evolution

Elucidation of the molecular phylogeny of soricomorph- and chiropteran-borne hantaviruses has been hampered by the paucity of full-length viral genomes, which in turn is due to the lack of viral isolates for nearly all of the newly identified non-rodent-borne hantaviruses. Employing well-established techniques and Vero E6 cells, preliminary attempts to isolate soricid- and talpid-borne hantaviruses from archival frozen tissues have failed (H.J. Kang and R. Yanagihara, unpublished observations). Future virus isolation attempts should be based on fresh tissues and possibly using various cell lines, including those established from reservoir shrew, mole and bat species.

The current non-rodent-borne hantavirus genomic database comprises partial and full-length sequences for 32 genetically distinct hantaviruses hosted by shrews, moles and bats (Figure 3). Of these, whole genomes are available for only six, and full-length S-segment sequences have been completed for 20. None of the bat-borne hantaviruses have been fully sequenced, and much remains to be done. In particular, full-length sequences of the M segment are generally lacking. Unfortunately, efforts at employing next generation sequencing technology have been thwarted by the limited availability of tissues and poor-quality of tissue RNA. Future success will depend on methodological refinements and optimally frozen or otherwise preserved tissue samples.

Previously, geographic-specific genetic variation has been demonstrated for Hantaan virus in the striped field mouse (Apodemus agrarius) (Song et al., 2000), Soochong virus in the Korean field mouse (Apodemus peninsulae) (Baek et al., 2006), Puumala virus in the bank vole (Myodes glareolus) (Garanina et al., 2009; Plyusnin et al., 1994, 1995; Plyusnina et al., 2009), Muju virus in the royal vole (Myodes regulus) (Song KJ et al., 2007), Tula virus in the European common vole (Microtus arvalis) (Schlegel et al., 2012a; Song et al., 2004) and Andes virus in the long-tailed colilargo (Oligoryzomys longicaudatus) (Medina et al., 2009). Similarly, phylogenetic analyses show that hantaviruses harbored by shrews (Kang et al., 2009a, 2011; Gu et al., 2011; Schlegel et al., 2012b; Yashina et al., 2010) and moles (Gu et al., 2013a) segregate along geographically specific lineages, suggesting long-standing associations between hantaviruses and their reservoir soricomorph hosts.

Phylogenetic analysis, based on partial or full genome sequences of all three segments, generated by maximum-likelihood and Bayesian methods, consistently revealed topologies, well supported by posterior node probabilities and bootstrap analysis, consisting of four distinct clades, comprising hantaviruses harbored by rodents of the Muridae family; by rodents of the Cricetidae family; by soricomorphs of the Soricidae family; and by one talpid mole species (Talpinae subfamily) and by insectivorous bats, which represent the most divergent hantaviruses found to date (Figure 4). Hantaviruses harbored by soricomorphs were divided into two phylogenetic lineages: one, which was paraphyletic with murid rodent-borne hantaviruses, included soricine and crocidurine shrew-borne hantaviruses, and two hantaviruses carried by shrew moles; the other lineage included TPMV and MJNV, two crocidurine shrew-associated hantaviruses, which were phylogenetically more closely related to bat-borne hantaviruses and two hantaviruses in myosoricine shrews.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic trees, based on the small (S) and large (L) genomic segments, respectively, of rodent-, shrew-, mole- and bat-borne hantaviruses, generated by the maximum-likelihood and Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo estimation methods, under the GTR+I+ model of evolution. Because tree topologies were similar when RAxML and MrBayes were used, the trees generated by MrBayes were displayed. The numbers at each node are Bayesian posterior node probabilities (>0.7) based on 150,000 trees (left) and bootstrap values of 1,000 replicates executed on the RAxML BlackBox web server (right), respectively. The scale bars indicate nucleotide substitutions per site. The phylogenetic positions are shown for Mouyassué virus ([MOYV] JQ287716) from the banana pipistrelle, Magboi virus (MGBV] JN037851) from the hairy slit-faced bat, Longquan virus ([LQUV] JX465413-JX465422, JX465379, JX465387) from horseshoe bats and Huangpi virus ([HUPV] JX473273, JX465369) from the Japanese house bat. Representative soricomorph-borne hantaviruses include Thottapalayam virus ([TPMV] AY526097, EU001330) from the Asian house shrew, Imjin virus ([MJNV] EF641804, EF641806) from the Ussuri white-toothed shrew, Jeju virus ([JJUV] HQ663933, HQ663935) from the Asian lesser white-toothed shrew, Tanganya virus ([TGNV] EF050455, EF050454) from the Therese’s shrew, Azagny virus ([AZGV] JF276226, JF276228) from the West African pygmy shrew, Cao Bang virus ([CBNV] EF543524, EF543525) from the Chinese mole shrew, Ash River virus ([ARRV] EF650086, EF619961) from the masked shrew, Jemez Springs virus ([JMSV] FJ593499, FJ593501) from the dusky shrew, Seewis virus ([SWSV] EF636024, EF636026) from the Eurasian common shrew, Kenkeme virus ([KKMV] GQ306148, GQ306150) from the flat-skulled shrew, Qiandao Lake virus ([QDLV] GU566023, GU566021) from the stripe-backed shrew, Camp Ripley virus ([RPLV] EF540771) from the northern short-tailed shrew, Asama virus ([ASAV] EU929072, EU929078) from the Japanese shrew mole, Oxbow virus ([OXBV] FJ539166, FJ593497) from the American shrew mole, Rockport virus ([RKPV] HM015223, HM015221) from the eastern mole, and Nova virus ([NVAV] FJ539168, FJ593498) from the European common mole. Also shown are representative rodent-borne hantaviruses, including Hantaan virus ([HTNV] NC_005218, NC_005222), Soochong virus ([SOOV SOO-1] AY675349, DQ562292), Dobrava-Belgrade virus ([DOBV] NC_005233, NC_005235), Seoul virus ([SEOV] NC_005236, NC_005238), Tula virus ([TULV] NC_005227, NC_005226), Puumala virus ([PUUV] NC_005224, NC_005225), Prospect Hill virus ([PHV] Z49098, EF646763), Andes virus ([ANDV] NC_003466, NC_003468), and Sin Nombre virus ([SNV] NC_005216, NC_005217).

The discrepancy in the phylogenetic positions of the crocidurine shrew-borne hantaviruses TPMV and MJNV and Longquan virus (LQUV), a Rhinolophus bat-borne hantavirus, in the S and L segment trees may be due to the very short L sequence for LQUV, compared to the full-length L sequences for TPMV and MJNV (Figure 4). By contrast, the S-segment tree, based on full-length sequences for all three viruses, is more robust. There was no discrepancy for NVAV, which was very distantly related to all other hantaviruses, forming a separate branch, strongly supported by posterior node probabilities, in the S- and L-genomic segment-based phylogenetic trees (Figure 4).

Host switching, or the movement of infectious agents from one species to another, has been well documented in parasite-host co-evolution and co-speciation. For hantaviruses, host-switching events have occurred between host species of the same family (Soricidae and Soricidae), of different families (Soricidae and Talpidae) and of separate orders (Soricomorpha and Rodentia). The importance of such virus-host switching lies in the emergence of disease-causing viruses, presumably through acquisition of gene sequences associated with virulence and tissue targeting or tropism. Accordingly, a better understanding about which specific nucleotide substitutions, or combinations of amino acid changes, are needed for species transfer will permit improved prediction of pathogen emergence and disease outbreaks (Bennett et al., 2014).

The notion of co-divergence was based on phylogenetic analyses of full-length hantaviral genomic sequences and host mitochondrial DNA or nuclear gene sequences, which showed that hantaviruses segregated into clades that paralleled the molecular phylogeny of rodents in the Murinae, Arvicolinae, Neotominae and Sigmodontinae subfamilies (Plyusnin et al., 1996). Recently, this concept has been vigorously challenged on the basis of the disjunction between the evolutionary rates of the host and virus species, in favor of preferential host switching and local host-specific adaptation (Ramsden et al., 2009). However, host-switching events alone do not completely explain the co-existence and distribution of genetically distinct hantaviruses among host species in three divergent taxonomic orders of small mammals spanning across four continents (Kang et al., 2009c). Moreover, phylogenetic trees reconstructed for co-phylogeny mapping, generated by TreeMap 2.0β, using consensus topologies based on amino acid sequences of the nucleocapsid protein, Gn and Gc glycoproteins and RNA-dependent RNA-polymerase, exhibited congruent segregation of hantaviruses according to the subfamily of their soricomorph reservoir hosts, with no evidence of host switching except for two hantaviruses carried by shrew moles (Kang et al., 2009b).

Because the sequence database of hantaviruses is far from complete, it is premature and ill advised to conclude that recent host-switching events coupled with subsequent divergence are singularly responsible for the similarities between the phylogenies of hantaviruses and their mammalian reservoir hosts. In short, the issue is not an either-or choice between host switching and co-divergence. Instead, the close association between distinct hantavirus clades and specific subfamilies of rodents, shrews and moles is likely the result of alternating and periodic episodes of host/pathogen co-divergence through deep evolutionary time (Kang et al., 2011a). That is, as evidenced by the overall congruence between the phylogenies of hantavirus genes and their rodent and soricomorph hosts, hantaviruses have likely co-diverged with specific reservoir hosts during part of their evolutionary history (Kang et al., 2009c, 2011a).

Conclusions

The long-held view that each genetically distinct hantavirus is carried by a single rodent species, with which it co-evolved, now appears to be overly simplistic, particularly in light of the expanded host range and genetic diversity of hantaviruses. Mention has already been made about host sharing. That is, certain hantaviruses, such as Tula virus, are harbored by more than one closely related rodent species (Klempa et al., 2013; Schmidt-Chanasit et al., 2010; Schlegel et al., 2012a). This seems to apply also to some hantaviruses hosted by soricine shrews (Gu et al., 2013b; Schlegel et al., 2012b) and insectivorous bats (Guo et al., 2013).

When viewed with in the context that soricomorphs and chiropterans harbor hantaviruses which are far more genetically diverse than hantaviruses hosted by rodents and that all other members of the Bunyaviridae family involve insect or arthropod hosts, the evolutionary origins of hantaviruses suggest that the primordial hantavirus may have been an insect virus which may have become adapted to an early soricomorph or chiropteran ancestor, with subsequent host switching many millions of years before the present. Investigations, now underway, in search of cryptic hantavirus-like sequences in arthropods and other terrestrial invertebrates may provide provocative insights into the evolutionary origins of hantaviruses.

Like their forefathers in Korea 40 years earlier who were faced with HFRS, a disease then unknown to American medicine, emergency physicians and health-care workers in the southwestern United States were confronted by hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS), a rapidly progressive cardiopulmonary disease in 1993 (Duchin et al., 1994). That a hantavirus, harbored by a neotomine rodent species identified as a reservoir host a decade earlier, would be responsible for this frequently fatal respiratory disease was beyond the collective imagination of clinicians, epidemiologists and medical virologists (Nerurkar et al., 1993, 1994; Nichol et al., 1993). The realization that rodent-borne hantaviruses are capable of causing diseases as clinically disparate as HFRS and HPS raises the possibility that newfound hantaviruses detected in shrews, moles and bats may similarly cause a wide spectrum of disease. Thus, one or more of the newly identified soricomorph- and chiropteran-borne hantaviruses may cause outbreaks of human disease and/or serve as surrogate antigens for the diagnosis of previously unrecognized hantaviral diseases.

Many more genetically distinct hantaviruses await discovery. This would have been unimaginable just a few years ago. But now, it would not be at all surprising if hantaviruses are found in other distantly related “insectivores”, such as hedgehogs and even tenrecs. In anticipation, new insights would be gained about the evolutionary origins and phylogeography of hantaviruses, and quite possibly the molecular determinants of pathogenicity.

Highlights.

Genetically distinct hantaviruses in shrews, moles and insectivorous bats herald a new frontier in hantavirology.

The evolutionary origins and phylogeography of hantaviruses are far more complex than previously conjectured.

Phylogenetic analyses suggest that soricomorphs and/or bats predated rodents as reservoir hosts of primordial hantaviruses.

Archival tissues have clarified the spatial and temporal distribution, host range and genetic diversity of hantaviruses.

Detection of hantavirus RNA in ethanol-fixed archival tissues expands the specimen pool for hantavirus-discovery efforts.

Acknowledgments

The collaborative contributions of the following individuals are gratefully acknowledged: Sergey A. Abramov, Luck Ju Baek, Shannon N. Bennett, Chris Conroy, Joseph A. Cook, Christiane Denys, Laurie Dizney, Paul E. Doetsch, Sylvain Dubey, Jake A. Esselstyn, Andrew G. Hope, Janusz Hejduk, Monika Hilbe, Jean-Pierre Hugot, Francois Jacquet, Blaise Kadjo, Michael Y. Kosoy, Takeshi Kurata, Eileen Lacey, Aude Lalis, Pawel P. Liberski, Burton K. Lim, Janusz Markowski, Shigeru Morikawa, Vivek R. Nerurkar, Violaine Nicolas, Satoshi D. Ohdachi, Nobuhiko Okabe, Maria Puorger, Luis A. Ruedas, Nuankanya Sathirapongsasuti, Beata Sikorska, Ki-Joon Song, William T. Stanley, Laarni Sumibcay, Ninh U. Truong, Thang T. Truong, Liudmila N. Yashina and Alex T. Yu. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grants R01AI075057 and P20GM103516) and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grant 24405045).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arai S, Song JW, Sumibcay L, Bennett SN, Nerurkar VR, Parmenter C, Cook JA, Yates TL, Yanagihara R. Hantavirus in northern short-tailed shrew, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13 (9):1420–1423. doi: 10.3201/eid1309.070484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai S, Bennett SN, Sumibcay L, Cook JA, Song JW, Hope A, Parmenter C, Nerurkar VR, Yates TL, Yanagihara R. Phylogenetically distinct hantaviruses in the masked hrew (Sorex cinereus) and dusky shrew (Sorex monticolus) in the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008a;78 (2):348–351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai S, Ohdachi SD, Asakawa M, Kang HJ, Mocz G, Arikawa J, Okabe N, Yanagihara R. Molecular phylogeny of a newfound hantavirus in the Japanese shrew mole (Urotrichus talpoides) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008b;105 (42):16296–16301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808942105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai S, Gu SH, Baek LJ, Tabara K, Bennett SN, Oh HS, Takada N, Kang HJ, Tanaka-Taya K, Morikawa S, Okabe N, Yanagihara R, Song JW. Divergent ancestral lineages of newfound hantaviruses harbored by phylogenetically related crocidurine shrew species in Korea. Virology. 2012;424 (2):99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai S, Nguyen ST, Boldgiv B, Fukui D, Araki K, Dang CN, Ohdachi SD, Nguyen NX, Pham TD, Boldbaatar B, Satoh H, Yoshikawa Y, Morikawa S, Tanaka-Taya K, Yanagihara R, Oishi K. Novel bat-borne hantavirus, Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19 (7):1159–1161. doi: 10.3201/eid1907.121549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek LJ, Kariwa H, Lokugamage K, Yoshimatsu K, Arikawa J, Takashima I, Kang JI, Moon SS, Chung SY, Kim EJ, Kang HJ, Song KJ, Klein TA, Yanagihara R, Song JW. Soochong virus: a genetically distinct hantavirus isolated from Apodemus peninsulae in Korea. J Med Virol. 2006;78 (2):290–297. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett SN, Gu SH, Kang HJ, Arai S, Yanagihara R. Reconstructing the evolutionary origins and phylogeography of hantaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.04.008. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey DE, Reuben R, Panicker KN, Shope RE, Myers RM. Thottapalayam virus: a presumptive arbovirus isolated from a shrew in India. Indian J Med Res. 1971;59 (11):1758–1760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SZ, Chen LL, Tao GF, Fu JL, Zhang CA, Wu YT, Luo LJ, Wang YZ. Strains of epidemic hemorrhagic fever virus isolated from the lungs of C. russula and A. squamipes. Chin J Prev Med. 1986;20 (5):261–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu YK, Rossi C, LeDuc JW, Lee HW, Schmaljohn CS, Dalrymple JM. Serological relationships among viruses in the Hantavirus genus, family Bunyaviridae. Virology. 1994;198 (1):196–204. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchin JS, Koster FT, Peters CJ, Simpson GL, Tempest B, Zaki SR, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Nichol S, Umland ET, Moolenaar RL, Reef SE, Nolte KB, Gallaher MM, Butler JC, Breiman RF Hantavirus Study Group. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome - a clinical description of 17 patients with a newly recognized disease. N Engl J Med. 1994;330 (14):949–955. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404073301401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garanina SB, Platonov AE, Zhuravlev VI, Murashkina AN, Yakimenko VV, Korneev AG, Shipulin GA. Genetic diversity and geographic distribution of hantaviruses in Russia. Zoonoses Public Health. 2009;56 (6–7):297–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2008.01210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilovskaya IN, Apekina NS, Myasnikov YA, Bernshtein AD, Ryltseva EV, Gorbachkova EA, Chumakov MP. Features of circulation of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) virus among small mammals in the European U.S.S.R. Arch Virol. 1983;75 (4):313–316. doi: 10.1007/BF01314898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gligic A, Stojanovic R, Obradovic M, Hlaca D, Dimkovic N, Diglisic G, Lukac V, Ler Z, Bogdanovic R, Antonijevic B, Ropac D, Avsic T, LeDuc JW, Ksiazek T, Yanagihara R, Gajdusek DC. Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in Yugoslavia: epidemiologic and epizootiologic features of a nationwide outbreak in 1989. Eur J Epidemiol. 1992;8 (6):816–825. doi: 10.1007/BF00145326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu SH, Kang HJ, Baek LJ, Noh JY, Kim HC, Klein TA, Yanagihara R, Song JW. Genetic diversity of Imjin virus in the Ussuri white-toothed shrew (Crocidura lasiura) in the Republic of Korea, 2004–2010. Virol J. 2011;8:56. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu SH, Dormion J, Hugot JP, Yanagihara R. High prevalence of Nova hantavirus infection in the European mole (Talpa europaea) in France. Epidemiol Infect Sep. 2013a;18:1–5. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813002197. ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu SH, Markowski J, Kang HJ, Hejduk J, Sikorska B, Liberski PP, Yanagihara R. Boginia virus, a newfound hantavirus harbored by the Eurasian water shrew (Neomys fodiens) in Poland. Virol J. 2013b;10 (1):160. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu SH, Nicolas V, Lalis A, Sathirapongsasuti N, Yanagihara R. Complete genome sequence analysis and molecular phylogeny of a newfound hantavirus harbored by the Doucet’s musk shrew (Crocidura douceti) in Guinea. Infect Genet Evol. 2013c;20:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo WP, Lin XD, Wang W, Tian JH, Cong ML, Zhang HL, Wang MR, Zhou RH, Wang JB, Li MH, Xu J, Holmes EC, Zhang YZ. Phylogeny and origins of hantaviruses harbored by bats, insectivores and rodents. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003159. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HJ, Arai S, Hope AG, Song JW, Cook JA, Yanagihara R. Genetic diversity and phylogeography of Seewis virus in the Eurasian common shrew in Finland and Hungary. Virol J. 2009a;6 (1):208. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HJ, Bennett SN, Dizney L, Sumibcay L, Arai S, Ruedas LA, Song JW, Yanagihara R. Host switch during evolution of a genetically distinct hantavirus in the American shrew mole (Neurotrichus gibbsii) Virology. 2009b;388 (1):8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HJ, Bennett SN, Sumibcay L, Arai S, Hope AG, Mocz G, Song JW, Cook JA, Yanagihara R. Evolutionary insights from a genetically divergent hantavirus harbored by the European common mole (Talpa europaea) PLoS ONE. 2009c;4 (7):e6149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HJ, Arai S, Hope AG, Cook JA, Yanagihara R. Novel hantavirus in the flat-skulled shrew (Sorex roboratus) Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10 (6):593–597. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HJ, Bennett SN, Hope AG, Cook JA, Yanagihara R. Shared ancestry between a mole-borne hantavirus and hantaviruses harbored by cricetid rodents. J Virol. 2011a;85 (15):7496–7503. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02450-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HJ, Kadjo B, Dubey S, Jacquet F, Yanagihara R. Molecular evolution of Azagny virus, a newfound hantavirus harbored by the West African pygmy shrew (Crocidura obscurior) in Côte d’Ivoire. Virol J. 2011b;8:373. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HJ, Kosoy MY, Shrestha SK, Shrestha MP, Pavlin JA, Gibbons RV, Yanagihara R. Genetic diversity of Thottopalayam virus, a hantavirus harbored by the Asian house shrew (Suncus murinus) in Nepal. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011c;85 (3):540–545. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klempa B, Fichet-Calvet E, Lecompte E, Auste B, Aniskin V, Meisel H, Denys C, Koivogui L, ter Meulen J, Krüger DH. Hantavirus in African wood mouse, Guinea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12 (5):838–840. doi: 10.3201/eid1205.051487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klempa B, Fichet-Calvet E, Lecompte E, Auste B, Aniskin V, Meisel H, Barriere P, Koivogui L, ter Meulen J, Krüger DH. Novel hantavirus sequences in shrew, Guinea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13 (3):520–522. doi: 10.3201/eid1303.061198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klempa B, Radosa L, Krüger DH. The broad spectrum of hantaviruses and their hosts in Central Europe. Acta Virol. 2013;57 (2):130–137. doi: 10.4149/av_2013_02_130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HW, Lee PW, Johnson KM. Isolation of the etiologic agent of Korean hemorrhagic fever. J Infect Dis. 1978;137 (3):298–308. doi: 10.1093/infdis/137.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PW, Amyx HL, Yanagihara R, Gajdusek DC, Goldgaber D, Gibbs CJ., Jr Partial characterization of Prospect Hill virus isolated from meadow voles in the United States. J Infect Dis. 1985a;152 (4):826–829. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.4.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PW, Gibbs CJ, Jr, Gajdusek DC, Yanagihara R. Serotypic classification of hantaviruses by indirect immunofluorescent antibody and plaque reduction neutralization tests. J Clin Microbiol. 1985b;22 (6):940–944. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.6.940-944.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes P, Klempa B, Clement J, Matthijnssens J, Gajdusek DC, Krüger DH, Van Ranst M. A proposal for new criteria for the classification of hantaviruses, based on S and M segment protein sequences. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9 (5):813–820. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina RA, Torres-Perez F, Galeno H, Navarrete M, Vial PA, Palma RE, Ferres M, Cook JA, Hjelle B. Ecology, genetic diversity and phylogeographic structure of Andes virus in humans and rodents in Chile. J Virol. 2009;83 (6):2446–2459. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01057-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meheretu Y, Cížková D, Têšíková J, Welegerima K, Tomas Z, Kidane D, Girmay K, Schmidt-Chanasit J, Bryja J, Günther S, Bryjová A, Leirs H, Goüy de Bellocq J. High diversity of RNA viruses in rodents, Ethiopia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18 (12):2047–2050. doi: 10.3201/eid1812.120596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerurkar VR, Song KJ, Gajdusek DC, Yanagihara R. Genetically distinct hantavirus in deer mice. Lancet. 1993;342 (8878):1058–1059. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92917-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerurkar VR, Song JW, Song KJ, Nagle JW, Hjelle B, Jenison S, Yanagihara R. Genetic evidence for a hantavirus enzootic in deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus) captured a decade before the recognition of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Virology. 1994;204 (2):563–568. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol ST, Spiropoulou CF, Morzunov S, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG, Feldmann H, Sanchez A, Childs J, Zaki S, Peters CJ. Genetic identification of a hantavirus associated with an outbreak of acute respiratory illness. Science. 1993;262 (5135):914–917. doi: 10.1126/science.8235615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plyusnin A, Vapalahti O, Ulfves K, Lehvaslaiho H, Apekina N, Gavrilovskaya I, Blinov V, Vaheri A. Sequences of wild Puumala virus genes show a correlation of genetic variation with geographic origin of the strains. J Gen Virol. 1994;75 (2):405–409. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-2-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plyusnin A, Vapalahti O, Lehvaslaiho H, Apekina N, Mikhailova T, Gavrilovskaya I, Laakkonen J, Niemimaa J, Henttonen H, Brummer-Korvenkontio M, Vaheri A. Genetic variation of wild Puumala viruses within the serotype, local rodent populations and individual animal. Virus Res. 1995;38 (1):25–41. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(95)00038-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plyusnin A, Vapalahti O, Vaheri A. Hantaviruses: genome structure, expression and evolution. J Gen Virol. 1996;77 (11):2677–2687. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-11-2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plyusnina A, Ferenczi E, Rácz GR, Nemirov K, Lundkvist A, Vaheri A, Vapalahti O, Plyusnin A. Co-circulation of three pathogenic hantaviruses: Puumala, Dobrava, and Saaremaa in Hungary. J Med Virol. 2009;81 (12):2045–2052. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radosa L, Schlegel M, Gebauer P, Ansorge H, Heroldová M, Jánová E, Stanko M, Mošanský L, Fričová J, Pejčoch M, Suchomel J, Purchart L, Groschup MH, Krüger DH, Ulrich RG, Klempa B. Detection of shrew-borne hantavirus in Eurasian pygmy shrew (Sorex minutus) in Central Europe. Infect Genet Evol. 2013 Apr 16; doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.04.008. pii: S1567-1348(13)00147-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsden C, Holmes EC, Charleston MA. Hantavirus evolution in relation to its rodent and insectivore hosts: no evidence for codivergence. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26 (1):143–153. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resman K, Korva M, Fajs L, Zidarič T, Trilar T, Zupanc TA. Molecular evidence and high genetic diversity of shrew-borne Seewis virus in Slovenia. Virus Res. 2013;177 (1):113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel M, Kindler E, Essbauer SS, Wolf R, Thiel J, Groschup MH, Heckel G, Oehme RM, Ulrich RG. Tula virus infections in the Eurasian water vole in Central Europe. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012a;12 (6):503–513. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel M, Radosa L, Rosenfeld UM, Schmidt S, Triebenbacher C, Löhr PW, Fuchs D, Heroldová M, Jánová E, Stanko M, Mošanský L, Fričová J, Pejčoch M, Suchomel J, Purchart L, Groschup MH, Krüger DH, Klempa B, Ulrich RG. Broad geographical distribution and high genetic diversity of shrew-borne Seewis hantavirus in Central Europe. Virus Genes. 2012b;45 (1):48–55. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0736-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Chanasit J, Essbauer S, Petraityte R, Yoshimatsu K, Tackmann K, Conraths FJ, Sasnauskas K, Arikawa J, Thomas A, Pfeffer M, Scharninghausen JJ, Splettstoesser W, Wenk M, Heckel G, Ulrich RG. Extensive host sharing of central European Tula virus. J Virol. 2010;84 (1):459–474. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01226-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JW, Baek LJ, Kim SH, Kho EY, Kim JH, Yanagihara R, Song KJ. Genetic diversity of Apodemus agrarius-borne Hantaan virus in Korea. Virus Genes. 2000;21 (3):227–232. doi: 10.1023/a:1008199800011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JW, Baek LJ, Song KJ, Skrok A, Markowski J, Bratosiewicz J, Kordek R, Liberski PP, Yanagihara R. Characterization of Tula virus from common voles (Microtus arvalis) in Poland: evidence for geographic-specific phylogenetic clustering. Virus Genes. 2004;29 (2):239–247. doi: 10.1023/B:VIRU.0000036384.50102.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JW, Baek LJ, Schmaljohn CS, Yanagihara R. Thottapalayam virus, a prototype shrewborne hantavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007a;13 (7):980–985. doi: 10.3201/eid1307.070031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JW, Gu SH, Bennett SN, Arai S, Puorger M, Hilbe M, Yanagihara R. Seewis virus, a genetically distinct hantavirus in the Eurasian common shrew (Sorex araneus) Virol J. 2007b;4:114. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JW, Kang HJ, Song KJ, Truong TT, Benneft SN, Arai S, Truong NU, Yanagihara R. Newfound hantavirus in Chinese mole hantavirus in Chinese mole shrew, Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007c;13 (11):1784–1787. doi: 10.3201/eid1311.070492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JW, Kang HJ, Gu SH, Moon SS, Bennett SN, Song KJ, Baek LJ, Kim HC, O’Guinn ML, Chong ST, Klein TA, Yanagihara R. Characterization of Imjin virus, a newly isolated hantavirus from the Ussuri white-toothed shrew (Crocidura lasiura) J Virol. 2009;83 (12):6184–6191. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00371-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song KJ, Baek LJ, Moon SS, Ha SJ, Kim SH, Park KS, Klein TA, Sames W, Kim HC, Lee JS, Yanagihara R, Song JW. Muju virus, a newfound hantavirus harbored by the arvicolid rodent Myodes regulus in Korea. J Gen Virol. 2007;88 (11):3121–3129. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83139-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza WM, Bello G, Amarilla AA, Alfonso HL, Aquino VH, Figueiredo LT. Phylogeography and evolutionary history of rodent-borne hantaviruses. Infect Genet Evol. 2013 Nov 25; doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.11.015. pii: S1567-1348(13)00431-0. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumibcay L, Kadjo B, Gu SH, Kang HJ, Lim BK, Cook JA, Song JW, Yanagihara R. Divergent lineage of a novel hantavirus in the banana pipistrelle (Neoromicia nanus) in Côte d’Ivoire. Virol J. 2012;9:34. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tkachenko EA, Ivanov AP, Donets MA, Miasnikov YA, Ryltseva EV, Gaponova LK, Bashkirtsev VN, Okulova NM, Drozdov SG, Slonova RA, Somov GP, Astakhova TI. Potential reservoir and vectors of haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) in the U.S.S.R. Ann Soc Belg Med Trop. 1983;63 (3):267–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S, Witkowski PT, Auste B, Nowak K, Weber N, Fahr J, Mombouli JV, Wolfe ND, Drexler JF, Drosten C, Klempa B, Leendertz FH, Krüger DH. Hantavirus in bat, Sierra Leone. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18 (1):159–161. doi: 10.3201/eid1801.111026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao SY, LeDuc JW, Chu YK, Schmaljohn CS. Phylogenetic analyses of virus isolates in the genus Hantavirus, family Bunyaviridae. Virology. 1994;198 (1):205–217. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav PD, Vincent MJ, Nichol ST. Thottapalayam virus is genetically distant to the rodent-borne hantaviruses, consistent with its isolation from the Asian house shrew (Suncus murinus) Virol J. 2007;4:80. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashina L, Abramov S, Gutorov V, Dupal T, Krivopalov A, Panov V, Danchinova G, Vinogradov V, Luchnikova E, Hay J, Kang HJ, Yanagihara R. Seewis virus: phylogeography of a shrew-borne hantavirus in Siberia, Russia. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10 (6):585–591. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller HG, Karabatsos N, Calisher CH, Digoutte JP, Cropp CB, Murphy FA, Shope RE. Electron microscopic and antigenic studies of uncharacterized viruses. II Evidence suggesting the placement of viruses in the family Bunyaviridae. Arch Virol. 1989;108 (3–4):211–227. doi: 10.1007/BF01310935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]