Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVE

It is expected that dairy products such as cheeses, which are the main source of cholesterol and saturated fat, may lead to the development or increase the risk of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases; however, the results of different studies are inconsistent. This study was conducted to assess the association between cheese consumption and cardiovascular risk factors in an Iranian adult population.

SUBJECTS/METHODS

Information from the Isfahan Healthy Heart Program (IHHP) was used for this cross-sectional study with a total of 1,752 participants (782 men and 970 women). Weight, height, waist and hip circumference measurement, as well as fasting blood samples were gathered and biochemical assessments were done. To evaluate the dietary intakes of participants a validated food frequency questionnaire, consists of 49 items, was completed by expert technicians. Consumption of cheese was classified as less than 7 times per week and 7-14 times per week.

RESULTS

Higher consumption of cheese was associated with higher C-Reactive Protein (CRP), apolipoprotein A and high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) level but not with fasting blood sugar (FBS), total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), triglyceride (TG) and apolipoprotein B. Higher consumption of cheese was positively associated with consumption of liquid and solid oil, grain, pulses, fruit, vegetable, meat and dairy, and negatively associated with Global Dietary Index. After control for other potential confounders the association between cheese intake and metabolic syndrome (OR: 0.81; 96%CI: 0.71-0.94), low HDL-C level (OR: 0.87; 96%CI: 0.79-0.96) and dyslipidemia (OR: 0.88; 96%CI: 0.79-0.98) became negatively significant.

CONCLUSION

This study found an inverse association between the frequency of cheese intake and cardiovascular risk factors; however, further prospective studies are required to confirm the present results and to illustrate its mechanisms.

Keywords: Cheese consumption, cardiovascular risk factors, food frequency questionnaire

INTRODUCTION

Despite the progresses in health care, cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the main cause of death worldwide [1]. Recently cardiovascular mortality is increasing in developing countries, mostly because of the influence of Western lifestyle, such as smoking, lack of physical activity and dietary habits. In Iran, as a developing country, CVDs are considered as the most leading causes of mortality [2] and there is a rising trend in its prevalence [3]. CVD occurred as a result of numerous risk factors such as, diabetes, obesity, high blood pressure, dyslipidemia and smoking [4]. Furthermore, dietary factors and life style patterns are more important in development of CVD [5]. Several investigations described the role of diet and nutrients in the expansion of metabolic diseases [6,7]. High intake of cholesterol and saturated fatty acids are associated with CVD mortality [8]. Despite the expectation that the dairy products (as a main source of cholesterol and saturated fat) may lead to development of CVD and metabolic diseases, the results of different studies are inconsistent. Although several studies have shown the hypercholesterolaemic effect of diets rich in dairy products, [9,10] others couldn't find any association between milk consumption and CVD [11]. Moreover, some studies showed positive effects on metabolic parameters as a result of consumption of milk products. These studies suggest that the intake of dairy products, as a good source of essential nutrients and high quality protein, may reduce the risk of heart disease [12,13]. Cheese as a high saturated fat dairy product, may increase cholesterol concentration and can be associated with higher CVD risk [14,15]; contrarily, cheese is a good source of calcium (Ca) that might reduce heart disease by influencing plasma lipid profiles [16], reduce blood pressure [17,18], and adiposity [19,20]. It has been claimed that the intake of fermented products like cheese is negatively associated with cholesterol concentration [21]. Previous investigations indicated that cheese may not have any unfavorable effect on lipid profiles [22] and that cheese may even have a cholesterol lowering effect [23]. A recent study reported that the frequency of consumption of cheese was negatively associated with serum TG and positively associated with serum HDL cholesterol [24]. In contrast, some studies found non-significant association between cheese consumption and heart disease [25,26]. Another study reported that cheese intake is positively associated with myocardial infarction [27]. Overall, due to inconsistent results, the effect of cheese on CVD risk factors has remained uncertain [28]. Cheese has been one of the most important dairy products in Iranian diet, especially for breakfast [29]. Furthermore, the studies on cheese and CVD risks were done in the western and developed countries with different lifestyle, and according to our knowledge there is no study from developing countries, particularly the Middle East region including Iran. Therefore, current study aimed to investigate the association between cheese intake and cardiovascular risk factors among Iranian people.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Participants

Information from the first phase of Isfahan Healthy Heart Program (IHHP) obtained for this cross-sectional study. Isfahan cardiovascular research institute and Isfahan provincial health office conducted the IHHP, which was a community-based program for cardiovascular prevention and control and healthy lifestyle promotion.

This study was completed in three provincial cities of Isfahan, Arak and Najafabad. Multistage cluster random sampling method was used for selecting individuals. More complete information about IHHP and sampling method is reported elsewhere [3,30]. Individuals who had dietary and anthropometric data, lipid profiles, plasma glucose and other biological measurements were included in this study. Individuals with history of chronic diseases or taking medications were excluded. Written informed consents were obtained from all participants who were 1,752 people (782 men and 970 women). The Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical approved the study.

Measurements

Trained interviewers collected demographic, socio-economic data, medical and family history, smoking habits, as well as physical activity level using pretested questionnaire. Height was measured in bare foot by a wall fixed measuring tape and weight was measured in light clothing by calibrated scale. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilogram divided by height in meters squared. Waist circumference at the smallest circumference between lowest rib and the iliac was horizontally measured and hip circumference measurement was done at the greatest point of hip.

Dietary habits

To evaluate dietary intakes of participants a validated food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) that consists 49 items was used by expert technicians. The validity of this food frequency questionnaire was confirmed by Medical Education Development Center before being used [3]. The frequency and the portion size of consumption during the previous year for each food item were individually asked. Global dietary index (GDI), expressing diet quality, was produced by calculating the average of the mean of 29 frequency questions in seven categories.

Biochemical assessment

Blood samples were collected after overnight fasting. Fasting blood samples were frozen at -70℃ until being assessed at the central laboratory of Isfahan Cardiovascular Research Institute. Measurement of fasting plasma glucose (FPG), serum total cholesterol and TG levels was done by enzymatic colorimetric method. Measurement of HDL-C cholesterol was completed subsequent to sedimentation of non-HDL cholesterol by dextran sulphate-magnesium chloride. Friedewald equation [31] was used to calculate serum LDL-C cholesterol level. Enzyme immunoabsorbent and immunoassay was used to measure Apo A and Apo B.

Having three or more factor of FBS > 126 mg/dl or waist > 102 cm for men and > 85 cm for women or TG > 150 mg/dl or HLD < 40 mg/dl for men and < 50 mg/dl for women or systolic blood pressure > 130 mmHg and diastolic > 85 mmHg has been considered as metabolic syndrome. Having one disorder in lipid profiles (Cholesterol > 240 mg/dl, LDL-C > 160 mg/dl, HDL-C < 40 mg/dl for men and < 50 mg/dl for women, TG > 200 mg/dl) has been considered as dyslipidemia.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS 15 software. Student's t test was applied for comparing means of continuous variables between categories of cheese intake. To compare categorical variables Chi-square test was used. Logistic regression in different models was used to explore the associations between categories of cheese consumption and cardiovascular risk factors. First, we adjusted for age and sex, in second model further adjustment was done for dietary intakes and physical activity and then a last adjustment was done for BMI. In all models cheese intake < 7 times per week was considered as the reference.

RESULTS

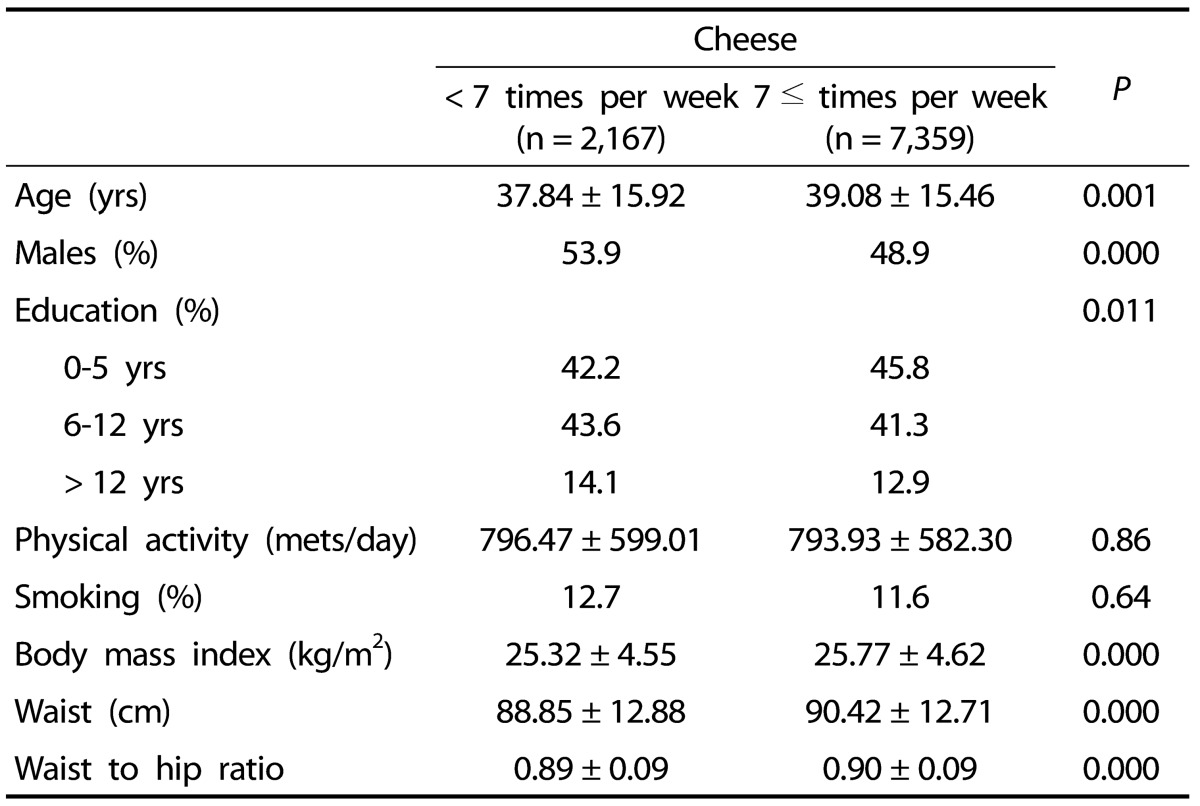

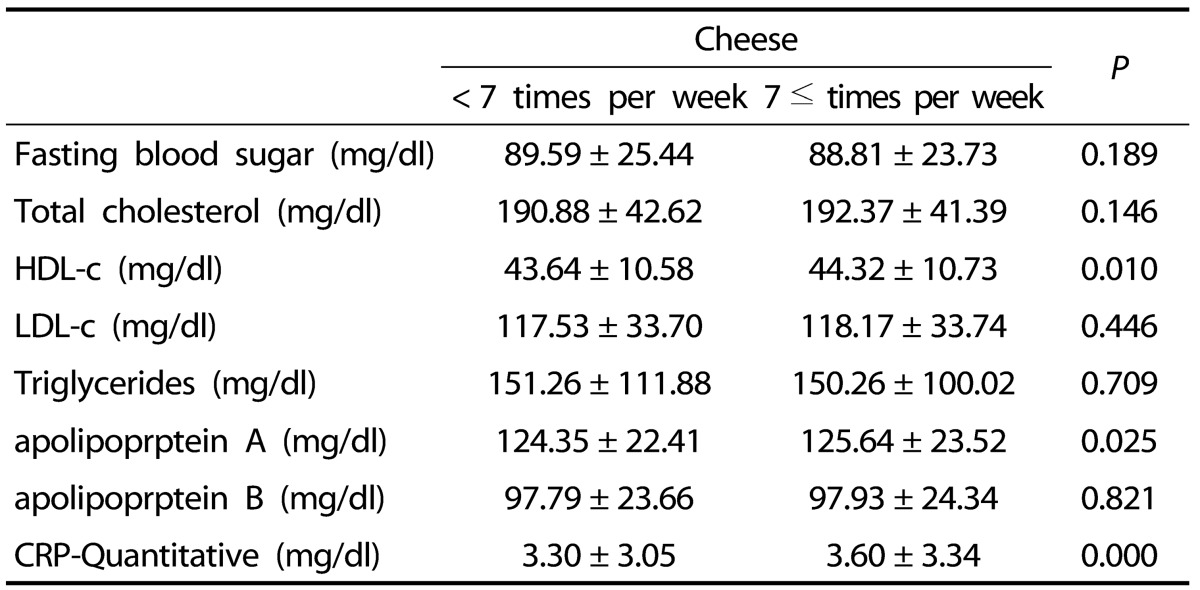

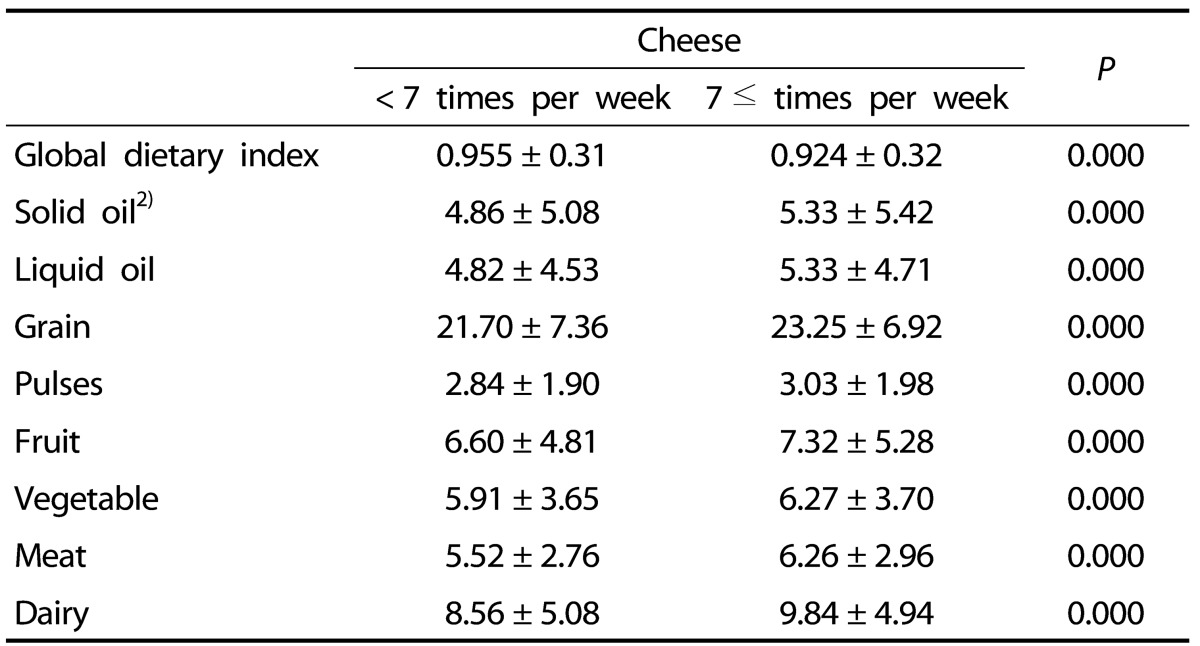

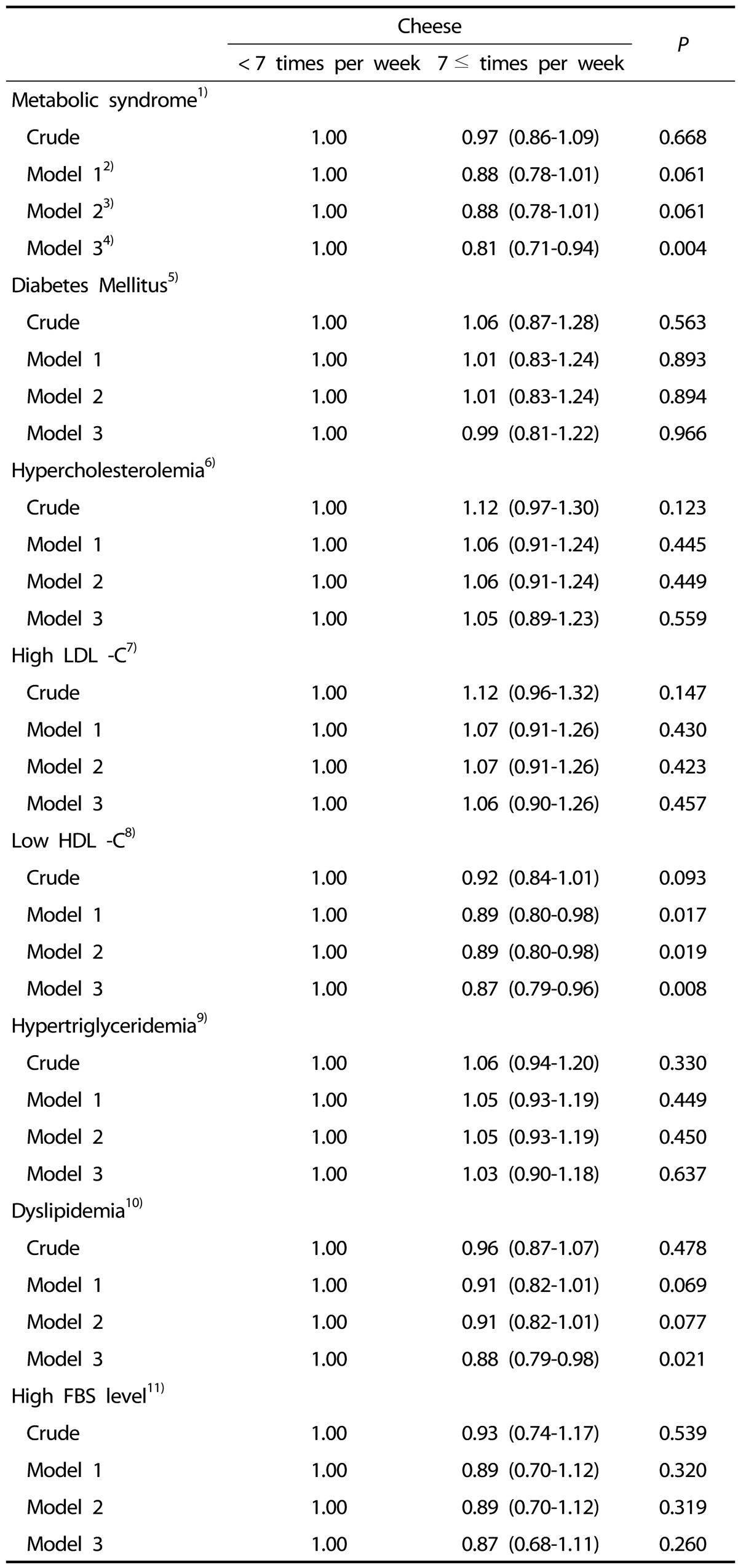

Characteristics of study participants by frequency of cheese consumption per week are presented in Table 1. Individuals who consumed more cheese (7 ≤ times per week) were older, mostly female, and tended to have higher BMI, waist and waist to hip ratio with different education status in comparison with people with lower cheese intake (< 7 times per week) group. No significant difference was found in physical activity and smoking between two groups. Table 2 indicates the cardiovascular risk factors of study participants by the frequency of cheese consumption. Higher consumption of cheese was associated with higher CRP, apolipoprotein A and HDL level but not with other cardiovascular risk factors including FBS, total cholesterol, LDL-C, TG and Apo B. Dietary intake of participants by frequency of cheese consumption are shown in Table 3. Higher consumption of cheese was positively associated with consumption of liquid and solid oil, grain, pulses, fruit, vegetable, meat and dairy products and negatively associated with Global Dietary Index. Crude and multivariate-adjusted odds ratio and 95% CI of cardiovascular risk factors in different groups of cheese intake are presented in Table 4. In crude model there was no difference between two groups but after adjustment for age and sex, low HDL level was negatively associated with cheese consumption (OR:0.89; 96% CI: 0.80-0.98). After control for other potential confounders such as dietary intakes and physical activity the association did not change. Further adjustment for BMI showed strong negative association between cheese intake with metabolic syndrome (OR:0.81; 96% CI: 0.71-0.94), low HDL level (OR:0.87; 96% CI: 0.79-0.96), and dyslipidemia (OR:0.88; 96%vCI: 0.79-0.98).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants by frequency of cheese consumption per week1)

1) Data are means ± standard deviation unless indicated.

Table 2.

Cardiovascular risk factors of study participants by frequency of cheese consumption per week1)

1) Data are means ± standard deviation.

HDL-c, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-c, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; CRP, c-reactive protein

Table 3.

Dietary intake of study participants by frequency of cheese consumption per week1)

1) Data are means ± standard deviation.

2) Dietary intakes are times per week.

Table 4.

Multivariate adjusted odds ratio for cardiovascular risk factors by frequency of cheese consumption per week

1) Having 3 or more factor: FBS > 126 mg/dl or waist > 102 cm for men and > 85 cm (for women) or TG > 150 mg/dl or HLD < 40 mg/dl for men and < 50 mg/dl for women or systolic blood pressure > 130 mmHg and diastolic > 85 mmHg.

2) Model 1: Adjusted for age and sex

3) Model 2: Adjusted for age, sex and dietary intakes and physical activity

4) Model 3: Further adjusted for BMI

5) FBS > 126 mg/dl or glucose 2 hpp > 200 mg/dl or using of hypoglycemic agents

6) Cholesterol > 240 mg/dl

7) LDL-C > 160 mg/dl

8) HDL-C > 40 mg/dl for men and > 50 mg/dl for women

9) TG > 200 mg/dl

10) Having one disorder in above lipid profiles

11) FBS > 126 mg/dl

DISCUSSION

In the present cross-sectional study as part of Isfahan Healthy Heart Program (IHHP), higher consumption of cheese was associated with lower cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors, which shows the beneficial effect of cheese intake. These results are apparently in contrast with previous knowledge about blood lipids and dietary fat consumption as cheese considered as a main source of saturated fat among dairy products. It has been reported that milk and dairy products consumption were positively correlated with total cholesterol, LDL-C and HDL-C levels [9]. In contrary, the consumption of milk and its products has been demonstrated to be negatively associated with the prevalence of metabolic syndrome [32]. These results are reported from various populations that consume different kinds of milk products, and this difference may be one possible reason for this inconsistency. For example, high consumption of milk in Scandinavian countries led to high mortality of heart disease whereas, high consumption of cheese in France may be one of the reasons of low heart disease mortality [33].

It is supposed that the effect of fat intake from cheese on serum lipids might be different from what expected from fat content. In a previous study a positive relationship was found between the intake of milk and heart disease mortality, although cheese consumption was negatively but not significantly correlated [25]. Another study showed a positive association between dairy fat intake and coronary heart diseases but the study recommended that cheese could be an exception [34]. Other studies also reported that individuals in higher category of cheese consumption were not at higher risk of myocardial infarction [28], hypertriglyceridemia [33] or high LDL-C level [35] than people consuming lower amount of cheese. It has been reported that cheese consumption could even reduce LDL-C in comparison with equal fat from butter [36].

Our finding that higher consumption of cheese can be inversely associated with cardiovascular risk factors including metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C level and hyperlipidemia is in accordance with other earlier investigations on cheese consumption, which showed positive association between the intake of cheese and HDL-C level [24], and a negative association with total cholesterol levels [37] and metabolic syndrome [38,39]. Nevertheless, a prospective study found a positive association between cheese intake and cholesterol level, as well as IHD mortality [40]. Other studies reported a positive association between cheeses consumption and metabolic syndrome [41], cardiovascular risk factors [14] and myocardial infarction [27]. Different results among various studies might be depended on different population samples, lifestyles and study design [39].

A possible mechanism for beneficial effect of cheese consumption could be the effect of the high content of calcium in cheese. Previous studies showed that dietary calcium with fat generate calcium soup and increase the excretion of lipid in feces [42] and significantly reduce serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels [43]. The effect of fermented dairy products on cholesterol concentration could be another mechanism for cheese effect. It has been suggested that the bacteria existed in large intestine convert unabsorbed carbohydrates to short-chain fatty acids, which could modify cholesterol synthesis in the liver. Also, these bacteria could bind bile acids to cholesterol and increase its excretion and reduce bile acid recycling [21]. Furthermore, high protein content of cheese, hypothesized as another possible mechanism for its effect on cholesterol [36].

Several limitations are considered in the current study. First, this study was designed as a cross-sectional study that makes decision on causality impossible. Second, to assess dietary intake we used qualitative FFQ that may lead to misclassification and underestimation and just give a crude estimate of the cheese intake, although it has been claimed that single FFQ ranks participants on total intake [44]. Third, there might be some residual confounding affecting the association between cheese consumption and cardiovascular risk factors, such as other lifestyle, dietary factors and dietary supplementation that were not controlled in our analysis. Finally we didn't know about the fat content of consumed cheese. The fat content of cheese is an important factor influencing the result of different studies.

In conclusion, we found an inverse association between frequency of cheese intake and cardiovascular risk factors; however, further prospective studies are required to confirm the present results and to illustrate the probable mechanism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The program was supported by grant No. 31309304 of the Iranian Budget and Planning Organization, as well as the Deputy for Health of the Iranian Ministry of Health, Treatment and Medical Education, and the Iranian Heart Foundation (IHF). We are grateful to the collaborating teams in ICRC, Isfahan Provincial Health Office, Najaf-Abad Health Office and Arak University of Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Writing Group Members; Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, Carnethon M, Dai S, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Ford E, Furie K, Gillespie C, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho PM, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lackland D, Lisabeth L, Marelli A, McDermott MM, Meigs J, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino M, Nichol G, Roger VL, Rosamond W, Sacco R, Sorlie P, Roger VL, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wong ND, Wylie-Rosett J American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:e46–e215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarraf-Zadegan N, Boshtam M, Malekafzali H, Bashardoost N, Sayed-Tabatabaei FA, Rafiei M, Khalili A, Mostafavi S, Khami M, Hassanvand R. Secular trends in cardiovascular mortality in Iran, with special reference to Isfahan. Acta Cardiol. 1999;54:327–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarraf-Zadegan N, Sadri G, Malek Afzali H, Baghaei M, Mohammadi Fard N, Shahrokhi S, Tolooie H, Poormoghaddas M, Sadeghi M, Tavassoli A, Rafiei M, Kelishadi R, Rabiei K, Bashardoost N, Boshtam M, Asgary S, Naderi G, Changiz T, Yousefie A. Isfahan Healthy Heart Programme: a comprehensive integrated community-based programme for cardiovascular disease prevention and control. Design, methods and initial experience. Acta Cardiol. 2003;58:309–320. doi: 10.2143/AC.58.4.2005288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helfand M, Buckley DI, Freeman M, Fu R, Rogers K, Fleming C, Humphrey LL. Emerging risk factors for coronary heart disease: a summary of systematic reviews conducted for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:496–507. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-7-200910060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khosravi-Boroujeni H, Mohammadifard N, Sarrafzadegan N, Sajjadi F, Maghroun M, Khosravi A, Alikhasi H, Rafieian M, Azadbakht L. Potato consumption and cardiovascular disease risk factors among Iranian population. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2012;63:913–920. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2012.690024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khosravi-Boroujeni H, Sarrafzadegan N, Mohammadifard N, Alikhasi H, Sajjadi F, Asgari S, Esmaillzadeh A. Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages in relation to the metabolic syndrome among Iranian adults. Obes Facts. 2012;5:527–537. doi: 10.1159/000341886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esmaillzadeh A, Boroujeni HK, Azadbakht L. Consumption of energy-dense diets in relation to cardiometabolic abnormalities among Iranian women. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:868–875. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011002680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renaud S, Lanzmann-Petithory D. Coronary heart disease: dietary links and pathogenesis. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4:459–474. doi: 10.1079/phn2001134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chi D, Nakano M, Yamamoto K. Milk and milk products consumption in relationship to serum lipid levels: a community-based study of middle-aged and older population in Japan. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2004;12:84–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moss M. Does milk cause coronary heart disease? J Nutr Environ Med. 2002;12:207–216. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elwood PC, Pickering JE, Hughes J, Fehily AM, Ness AR. Milk drinking, ischaemic heart disease and ischaemic stroke II. Evidence from cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:718–724. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mennen LI, Lafay L, Feskens EJ, Novak M, Lépinay P, Balkau B. Possible protective effect of bread and dairy products on the risk of the metabolic syndrome. Nutr Res. 2000;20:335–347. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pereira MA, Jacobs DR, Jr, Van Horn L, Slattery ML, Kartashov AI, Ludwig DS. Dairy consumption, obesity, and the insulin resistance syndrome in young adults: the CARDIA Study. JAMA. 2002;287:2081–2089. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Ascherio A, Colditz GA, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH, Willett WC. Dietary saturated fats and their food sources in relation to the risk of coronary heart disease in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:1001–1008. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.6.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McNamara DJ, Lowell AE, Sabb JE. Effect of yogurt intake on plasma lipid and lipoprotein levels in normolipidemic males. Atherosclerosis. 1989;79:167–171. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(89)90121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacqmain M, Doucet E, Després JP, Bouchard C, Tremblay A. Calcium intake, body composition, and lipoprotein-lipid concentrations in adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1448–1452. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.6.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hajjar IM, Grim CE, Kotchen TA. Dietary calcium lowers the age-related rise in blood pressure in the United States: the NHANES III survey. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2003;5:122–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2003.00963.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jorde R, Bonaa KH. Calcium from dairy products, vitamin D intake, and blood pressure: the Tromsø Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1530–1535. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loos RJ, Rankinen T, Leon AS, Skinner JS, Wilmore JH, Rao DC, Bouchard C. Calcium intake is associated with adiposity in Black and White men and White women of the HERITAGE Family Study. J Nutr. 2004;134:1772–1778. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.7.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zemel MB, Miller SL. Dietary calcium and dairy modulation of adiposity and obesity risk. Nutr Rev. 2004;62:125–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.St-Onge MP, Farnworth ER, Jones PJ. Consumption of fermented and nonfermented dairy products: effects on cholesterol concentrations and metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:674–681. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.3.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colquhoun DM, Somerset S, Irish K, Leontjew LM. Cheese added to a low fat diet does not affect serum lipids. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2003;12 Suppl:S65. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tholstrup T, Høy CE, Andersen LN, Christensen RD, Sandström B. Does fat in milk, butter and cheese affect blood lipids and cholesterol differently? J Am Coll Nutr. 2004;23:169–176. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Høstmark AT, Haug A, Tomten SE, Thelle DS, Mosdøl A. Serum hdl cholesterol was positively associated with cheese intake in the Oslo Health Study. J Food Lipids. 2009;16:89–102. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moss M, Freed D. The cow and the coronary: epidemiology, biochemistry and immunology. Int J Cardiol. 2003;87:203–216. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldbohm RA, Chorus AM, Galindo Garre F, Schouten LJ, van den Brandt PA. Dairy consumption and 10-y total and cardiovascular mortality: a prospective cohort study in the Netherlands. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:615–627. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.000430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kabagambe EK, Baylin A, Siles X, Campos H. Individual saturated fatty acids and nonfatal acute myocardial infarction in Costa Rica. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:1447–1457. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tavani A, Gallus S, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Milk, dairy products, and coronary heart disease. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:471–472. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.6.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alizadeh M, Hamedi M, Khosroshahi A. Optimizing sensorial quality of iranian white brine cheese using response surface methodology. J Food Sci. 2005;70:S299–S303. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarrafzadegan N, Baghaei A, Sadri G, Kelishadi R, Malekafzali H, Boshtam M, Amani A, Rabie K, Moatarian A, Rezaeiashtiani A, Paradis G, O'Loughlin J. Isfahan healthy heart program: evaluation of comprehensive, community-based interventions for non-communicable disease prevention. Prev Control. 2006;2:73–84. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elwood PC, Pickering JE, Fehily AM. Milk and dairy consumption, diabetes and the metabolic syndrome: the Caerphilly prospective study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:695–698. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.053157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biong AS, Müller H, Seljeflot I, Veierød MB, Pedersen JI. A comparison of the effects of cheese and butter on serum lipids, haemostatic variables and homocysteine. Br J Nutr. 2004;92:791–797. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renaud S, De Lorgeril M. Dietary lipids and their relation to ischaemic heart disease: from epidemiology to prevention. J Intern Med Suppl. 1989;731:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1989.tb01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nestel PJ, Chronopulos A, Cehun M. Dairy fat in cheese raises LDL cholesterol less than that in butter in mildly hypercholesterolaemic subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59:1059–1063. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hjerpsted J, Leedo E, Tholstrup T. Cheese intake in large amounts lowers LDL-cholesterol concentrations compared with butter intake of equal fat content. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:1479–1484. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.022426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Samuelson G, Bratteby LE, Mohsen R, Vessby B. Dietary fat intake in healthy adolescents: inverse relationships between the estimated intake of saturated fatty acids and serum cholesterol. Br J Nutr. 2001;85:333–341. doi: 10.1079/bjn2000279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azadbakht L, Mirmiran P, Esmaillzadeh A, Azizi F. Dairy consumption is inversely associated with the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in Tehranian adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:523–530. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Høstmark AT, Tomten SE. The Oslo Health Study: cheese intake was negatively associated with the metabolic syndrome. J Am Coll Nutr. 2011;30:182–190. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2011.10719959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Appleby PN, Thorogood M, Mann JI, Key TJ. The Oxford Vegetarian Study: an overview. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:525S–531S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.3.525s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beydoun MA, Gary TL, Caballero BH, Lawrence RS, Cheskin LJ, Wang Y. Ethnic differences in dairy and related nutrient consumption among US adults and their association with obesity, central obesity, and the metabolic syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1914–1925. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobsen R, Lorenzen JK, Toubro S, Krog-Mikkelsen I, Astrup A. Effect of short-term high dietary calcium intake on 24-h energy expenditure, fat oxidation, and fecal fat excretion. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:292–301. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yacowitz H, Fleischman AI, Bierenbaum ML. Effects of oral calcium upon serum lipids in man. Br Med J. 1965;1:1352–1354. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5446.1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersen LF, Johansson L, Solvoll K. Usefulness of a short food frequency questionnaire for screening of low intake of fruit and vegetable and for intake of fat. Eur J Public Health. 2002;12:208–213. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/12.3.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]