Abstract

Mass spectrometry of intact soluble protein complexes has emerged as a powerful technique to study the stoichiometry, structure-function and dynamics of protein assemblies. Recent developments have extended this technique to the study of membrane protein complexes where it has already revealed subunit stoichiometries and specific phospholipid interactions. Here, we describe a protocol for mass spectrometry of membrane protein complexes. The protocol begins with preparation of the membrane protein complex enabling not only the direct assessment of stoichiometry, delipidation, and quality of the target complex, but also evaluation of the purification strategy. A detailed list of compatible non-ionic detergents is included, along with a protocol for screening detergents to find an optimal one for mass spectrometry, biochemical and structural studies. This protocol also covers the preparation of lipids for protein-lipid binding studies and includes detailed settings for a Q-ToF mass spectrometer after introduction of complexes from gold-coated nanoflow capillaries.

INTRODUCTION

Membrane proteins are responsible for a wide range of biological functions. Some of the most prevalent human diseases, including some cancers, result from their dysfunction1,2. Despite representing only around a third of the human genome, they represent more than half of all current therapeutic agents1,2. As a significant biological target in disease and cancer, their study by traditional structural biology approaches, such as X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance, has been frustrated by limitations relating to their expression and solubility. Furthermore, X-ray analysis, in the majority of cases, has been limited by crystallographic resolution hindering the assignment of bound moieties. In contrast to classical structural biology methods, mass spectrometry (MS) of intact complexes, sometimes referred to as native MS, is a rapid and sensitive technique that can provide invaluable information on protein complexes, such as specifically bound small molecules.

Recent advances in MS have led to the first electrospray mass spectra of membrane protein complexes. Typically high concentrations of detergent are used to solubilize membrane proteins leading to solutions containing heterogeneous detergent micelles. Due to the presence of detergent, membrane protein complexes initially eluded analysis by MS methods until the realization that they could be transferred to the gas-phase while still encapsulated in detergent micelles3. From this initial discovery, biological membrane-embedded machines, such as the ATP-binding cassette transporter (BtuC2D2)3, have been analyzed by MS (for review see 4).

To date, the largest membrane protein complexes analyzed by MS has been V-Type ATPases from Thermus thermophiles and Enterococcus hirae 5. These molecular machines are assembled from nine different proteins consisting of 26 subunits with calculated masses of ~700 kDa. Surprisingly, these large complexes could be transmitted into the mass spectrometer while preserving soluble and membrane subunit interactions. Once in the mass spectrometer, experimental measurements revealed subunit stoichiometries for these two ATPases, revealing the number of peripheral stalks and the stoichiometry of the K ring, areas of controversy in the field. Tightly bound lipids within the membrane rings were also identified, highlighting the ability of this technique to maintain non-covalent interactions in the gas-phase and to provide novel insight into the composition and stoichiometry of specific lipid binding.

Structural biologists and biochemists are interested in the effect of detergents on membrane protein structure and function. Traditionally, membrane proteins are solubilized in different detergents and monodispersity is judged by their trace from gel filtration chromatography6-8. This process provides low resolution and qualitative information. Here, we outline a protocol describing a MS-compatible detergent screen for membrane proteins that enables acquisition of mass spectra and assessment of the homogeneity of the complex. The protocol can also be extended to high-throughput detergent screening. Moreover, with the variety of non-ionic detergents becoming available, we anticipate that it will be possible to obtain mass spectra for most membrane protein complexes after carrying out the detergent screen methodology described herein. Although emphasis here has been placed on improving the quality of mass spectra, screening detergents for their ability to improve purity, stability, and homogeneity of membrane protein complexes are highly desirable attributes sought by crystallographers9,10. MS of intact membrane protein complexes is set to become an indispensable tool for membrane protein biochemical and structural studies.

How are membrane protein complexes prepared for MS?

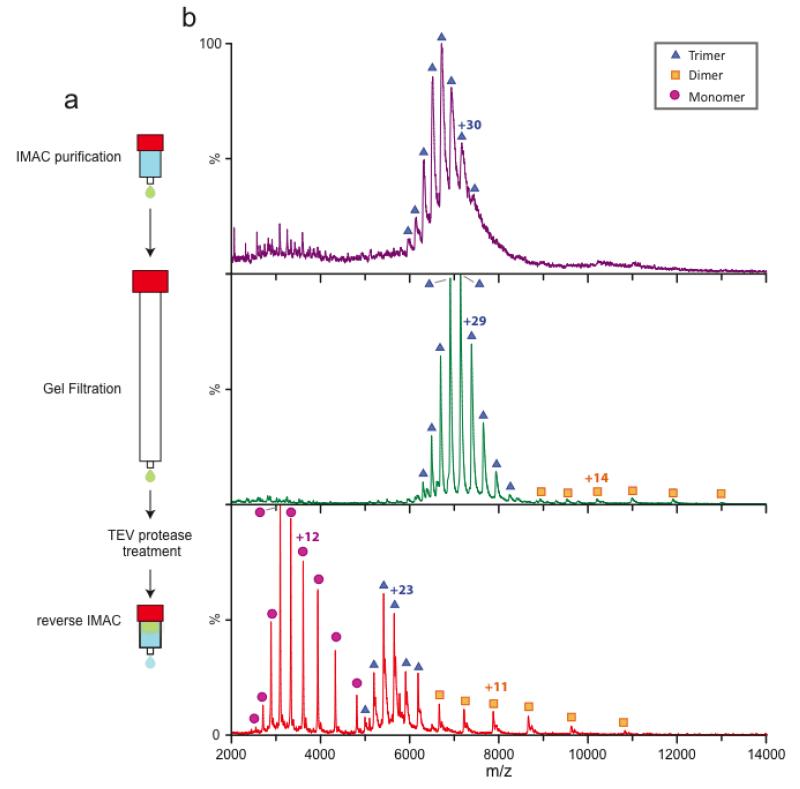

In brief, purified membrane protein complexes are buffer exchanged into an MS-compatible buffer. In our lab, we routinely express membrane proteins with a protease cleavable fusion, such as green fluorescent protein (GFP) containing a terminal his-tag. Membrane protein fusions are purified by immobilized affinity chromatography (IMAC), and sometimes purified further by gel filtration (Figure 1). Prior to MS analysis, purified protein is buffer exchanged into MS-compatible buffer supplemented with detergent using either centrifugal devices or by gel filtration.

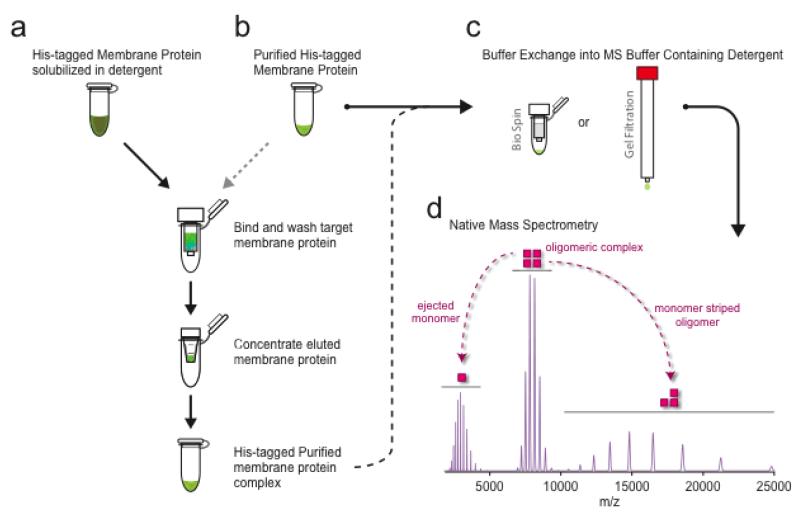

Figure 1. An overview of a typical membrane protein purification and preparation, and analysis by mass spectrometry of the intact complex.

(a) Purified membranes containing over-expressed membrane protein fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP) and His-tag is solubilized in a detergent of interest. Solubilized membrane protein is purified using immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) and concentrated prior to preparation for native mass spectrometry (MS). (b) Detergent can be screened or optimized starting with a purified membrane protein and follow the procedure outlined above to exchange into a different detergent. Furthermore, membrane proteins can be prepared from solubilized membranes in different detergents followed by purification using IMAC. (c) Purified membrane proteins are buffer exchanged into an MS-compatible buffer containing two times the critical micelle concentration (CMC) of the detergent of interest. Typically buffer exchange centrifugal devices, such as a Bio Spin device, are used. Alternatively, buffer exchange can also be achieved using a small analytical gel filtration column. (d) Theoretical mass spectrum for a tetrameric membrane protein complex (200 kDa) with a protein monomeric mass of 50 kDa. Under MS conditions, the oligomeric or tetrameric complex, centered around 8,500 m/z, undergoes collisional induced disassociation. Activation results in the ejection of a highly charged monomer, centered around 3,500 m/z, and a monomer stripped oligomer or oligomeric complex minus the ejected monomer, spanning the region 10,000 to 25,000 m/z.

How are mass spectra obtained and optimized for membranes proteins?

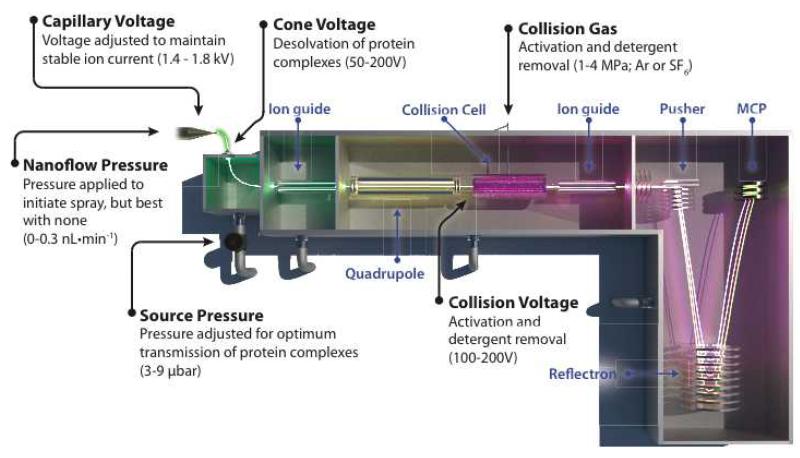

Membrane protein MS first involves the ionization of purified protein within detergent containing solutions by means of nano-electrospray (nanoES) and transmission into the mass spectrometer (Figure 2), presumably as charged complexes surrounded by detergent micelles. In order to obtain well-resolved charge state distributions, that enable mass measurements, removal of detergent through thermal activation is required. This is achieved by applying increasing collisional activation, following their transmission through the quadrupole mass analyser (Figure 2). Ions are accelerated into the collision cell containing an inert gas, such as Argon, resulting in detergent removal and release of the intact ionized protein assembly3. After passage through a second radio-frequency ion guide, packets of ions are transmitted by the pusher for separation in the time of flight mass analyser. Finally ions are detected at the microchannel plate detector (MCP). Interestingly, mass spectra reveal that some membrane proteins maintain interactions with detergent and/or lipid molecules even after collisional activation, such as detergent with BtuC2D23 and lipids with V-Type ATPases5. In some cases, these interactions cannot be removed even at the highest activation limits of commercial instrumentation.

Figure 2. Schematic of a Q-TOF mass spectrometer used for mass measurements of intact membrane protein complexes.

Parts of the instrument are labeled in blue and parameters described in this protocol are labeled in black with ranges of typical operating settings in parenthesis. A membrane protein complex undergoes nanoelectrospray through the applied capillary voltage and ionized species are desolvated prior to transmission into the MS (green ion beam). The ions enter the source where the pressure is raised to increase the transmission efficiency of large protein complexes. Next, ions pass through the quadrupole (yellow ion beam) prior to being accelerated into the collision cell (purple ion beam) filled with inert gas molecules to release the protein complex from the detergent micelle. The resulting activated species are transferred to the time-of-flight (TOF) section, where ion species are resolved by their time to traverse a known distance. Shown here is the trajectory for ions of an oligomeric complex (red ion beam) and the resulting activated species, ejected monomer (blue ion beam) and stripped oligomer (green ion beam). Note that the ejected monomer and stripped oligomer ion paths are shorter and longer, respectively, compared to the parent oligomeric complex.

Collisional activation not only liberates membrane protein complexes from detergent micelles but can also result in the dissociation of protein complexes. Activation can lead to local structural unfolding and upon further activation a threshold is reached whereby an unfolded protein subunit is ejected from the protein complex. The charge of the parent complex is typically divided asymmetrically among these activated products, resulting in a highly charged protein subunit and a charge stripped protein complex minus the ejected protein subunit11,12. This behavior is analogous to the dissociation of soluble protein complexes13. For example, a collisionally activated tetrameric protein complex will result in an ejected monomer and a stripped trimer (Figure 1d). For many protein assemblies, increased resolution is obtained for the stripped complex following loss of a protein subunit. The process therefore aids the assignment of subunit stoichiometry and composition of oligomeric protein complexes. Throughout this paper we refer to the oligomeric complex which has lost a subunit by defining the new oligomeric state preceded by ‘stripped’. In summary optimal conditions for membrane protein complexes is a compromise between achieving sufficient detergent removal while minimizing collisional activation, one of the subjects of this protocol.

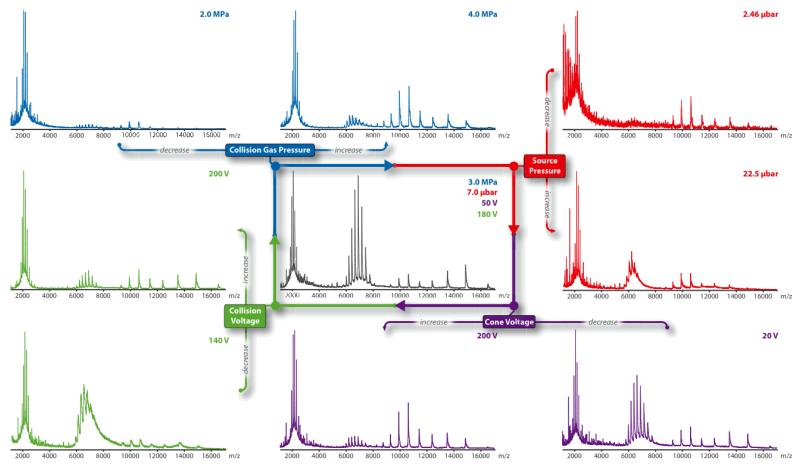

To achieve these optimal settings, mass spectrometer parameters are tuned for maximal desolvation and detergent removal while attempting minimal protein activation. Optimization of the following parameters is imperative: collision voltage, cone voltage, collision gas pressure, and source pressure (Figure 3). A general strategy employed for optimization is to first set the instrument parameters to relatively high activation settings for membrane protein complexes. Then iteratively, each of the four parameters is adjusted to produce resolved mass spectra while minimizing over-activation of the target complex (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Optimization scheme of critical mass spectrometer parameters for membrane protein native MS.

Four mass spectrometer parameters are optimized for the membrane protein complex of interest: collision gas pressure (blue), source pressure (red), cone voltage (purple), and collision energy (green). Shown here are the effects of altering individual mass spectrometer parameters on the pentameric ligand-gated ion channel of Erwinia chrysanthemi (ELIC)22 from optimized mass spectrometer conditions (grey spectra). Optimized conditions for the center spectrum are shown in the upper right as color-coded text to individual parameters described above. In general, optimization is achieved by adjusting parameters to maximize resolution and transmission of the oligomeric membrane protein complex. Collision gas, usually Argon, and sometimes SF6, at low operating pressures results in inefficient detergent micelle removal whereas at high pressures it lowers the transmission of oligomeric complexes. Higher source pressure is necessary to transmit large ions, however excessive pressure whether lower or higher lead to poor transmission of ions or peak broadening, respectively. The majority of activation of membrane protein complexes is achieved through adjusting the cone and collision energy voltages. Typically the collision energy is set to a higher value compared to the cone voltage. These two parameters are adjusted to produce resolved spectra while trying not to over activate the oligomeric complex, for example when collision energy is set to 200 V in this example.

What are the current MS-related limitations?

At present, modest collisional activation is required to remove membrane protein complexes from the detergent micelle. Although this activation is useful for removing detergent, the result is often local unfolding of protein structure and therefore, in general, the technique is not suitable for ion mobility MS studies; a technique to measure the structural topology of protein complexes14. Despite this limitation, recent studies have shown the potential of ion-mobility MS on membrane proteins under these elevated activation conditions15, suggesting that much of the internal energy gained through collisional activation is dissipated through detergent removal.

General guidelines for MS of membrane proteins

MS of membrane protein complexes can become routine when some general guidelines are followed:

(i) Buffer Conditions

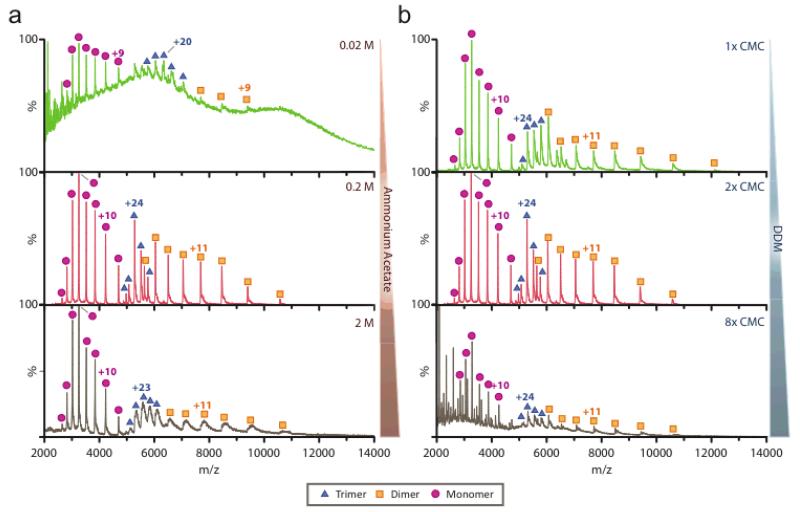

Membrane protein complexes are exchanged into ammonium acetate buffer containing the detergent of interest. The concentration of ammonium acetate is usually 200mM, but this can be adjusted to concentrations of up to 3M. However, decreasing or increasing ammonium acetate concentrations can result in poor quality mass spectra (Figure 4a), although this can be protein dependent. The pH of the buffers can be adjusted in the range of 5-8. When working with proteins containing His-tags we recommend using pH 8 to avoid protein insolubility/precipitation in lower pH buffered solutions.

Figure 4. Effect of ammonium acetate and detergent concentration on mass spectra of the E. coli ammonium channel, AmtB.

Mass spectra were collected at constant high activation instrument settings. (a) Purified trimeric AmtB channel17 was buffer exchanged into Mem MS Buffer containing 2× CMC DDM at various concentrations of ammonium acetate. Lower and higher buffer concentrations diminish mass spectra quality. (b) Dilution and addition of DDM to solutions of buffer exchanged AmtB in 200 mM ammonium acetate. Moderate and considerable resolution is lost in 1× and 8× CMC preparations, respectively. At high detergent concentrations, broad peaks are observed corresponding to detergent aggregates, for example in the 2,000 to 4,000 m/z range of the 8× CMC mass spectrum.

(ii) Mistakes related to detergent concentration

An error often observed is unknowingly concentrating detergent micelles in addition to the target membrane protein. High concentrations of detergent can not only cause protein instability, but can also lead to higher than expected concentrations of detergent in buffer exchanged samples (following step 1a) which can result in poor mass spectra (Figure 4b). Care should be taken when choosing the appropriate device for concentrating the complex to avoid concentrating detergent micelles16. We routinely use 100 kDa molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) concentrators for membrane proteins purified in DDM to avoid concentration of DDM micelles (~70 kDa) which would happen if using a ≤50 kDa MWCO concentrator.

Another common mistake is to decrease the detergent concentration below the critical micelle concentration (CMC, see Table 1) in the buffer exchange step. The thinking is that this will improve mass spectra. However this generally doesn’t lead to improved spectra, rather instability of the membrane protein complex in solution (Figure 4b). We strongly recommend maintaining the detergent of interest at two times the CMC value.

Table 1. Non-ionic detergents compatible with mass spectrometry of intact membrane protein complexes.

| Detergent | Abbreviation | CMC (%)b |

|---|---|---|

| Glucosides | ||

| n-Octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside | OG | 0.53 |

| n-Nonyl- β -D-glucopyranoside | NG | 0.2 |

| Thioglucosides | ||

| n-Octyl- β -D-thioglucopyranoside | OTG | 0.28 |

| Maltosides | ||

| n-Decyl- β -D-maltopyranoside | DM | 0.087 |

| n-Dodecyl- β -D-maltopyranoside | DDM | 0.0087 |

| n-Undecyl- β -D-maltopyranoside | UDM | 0.029 |

| n-Tridecyl- β -D-maltopyranoside | TDM | 0.0017 |

| Cymal-5 | Cy5 | 0.12 |

| Cymal-6 | Cy6 | 0.028 |

| Thiomaltosides | ||

| n-Dodecyl- β -D-thiomaltopyranoside | DDTM | 0.0026 |

| Alkyl Glycosides | ||

| Octyl Glucose Neopentyl Glycol | OGNG | 0.058 |

| Polyoxyethylene Glycols a | ||

| Triton X-100 | TX100 | 0.015 |

| C8E4 | C8E4 | 0.25 |

| C8E5 | C8E5 | 0.25 |

| C10E5 | C12E8 | 0.031 |

| C12E8 | C12E8 | 0.0048 |

| C12E9 | C12E9 | 0.003 |

| Anapoe-58 (Brij-58) | C16E20 | 0.00045 |

Depending on the membrane protein, this family of detergents in particular may produce complicated mass spectra.

Critical micelle concentration (CMC) obtained from manufacturer.

(iii) Detergent compatibility

The non-ionic detergent DDM has proved the most successful to date. Here we include many other non-ionic detergents identified via a systematic screen. Several of these detergents not only improve resolution but also lower the activation energy requirements to obtain resolved mass spectra (Table 1). A detergent that is compatible with electrospray does not necessarily imply that the membrane protein-detergent combination will be successful in producing well-resolved mass spectra. No membrane protein complexes have yet been analyzed by MS directly from solutions containing ionic detergents.

(iv) Protein requirements

Membrane proteins should ideally be relatively pure and homogenous, equivalent to crystallographic-grade material. The membrane protein preparation is crucial for success. Homogeneous complexes not only tend to produce high quality mass spectra but also reduce the difficulty in optimizing the MS parameters. Typical analysis requires a purified protein complex to be exchanged into an MS-compatible buffer with the final concentration of the complex in the low μM to high nM range (Supplementary Figure 1). It should be noted that MS is very sensitive. We have recorded mass spectra for complexes from solution concentrations of < 10 nM (Supplementary Figure 1). Routine experiments consume only a few microliters of the complex in the buffer-exchanged solution.

What information will I obtain from this protocol?

The following can be obtained:

(i) Stoichiometry

From a well-resolved mass spectrum, the composition of the membrane protein complex and associated adducts (if present) can be determined with precision. In some cases when the individual subunits are known, composition is calculated directly from summing the individual components to equal the measured mass. In practice, collisional activation is used to obtain masses of activated species to back calculate the stoichiometry of the parent oligomer.

(ii) Monitoring purification

We have observed that membrane proteins with fusion tags are more stable in the gas phase and do not disassociate as readily as their counterparts with fusion tags removed. In addition to this observation, we observe improved resolution for membrane protein complexes as a function of purification (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure 2). For example, initial purification using IMAC of the trimeric E. coli ammonium channel17, fused to a protease cleavable GFP (AmtB-GFP), leads to broad peaks in the mass spectrum, even at high activation energies. In some cases, lipids may be bound to the membrane protein complexes at this stage. Generally these are removed subsequently in additional purification steps. Gel filtration chromatography, following IMAC purification, leads to improved resolution of the mass spectra along with a higher signal-to-noise ratio. After protease treatment, to remove the fusion tag, and reverse IMAC the mass spectra have not only improved in resolution but also reveal more dissociation in the form of stripped dimer and highly charged monomer. This phenomenon of increased dissociation has been observed for several proteins after the fusion tags have been removed; typically the mass spectra are also of similar or better quality than those recorded for the complex with fusion tags retained. Therefore, dissociation of the membrane protein complex can be manipulated by the addition of a fusion partner.

Figure 5. Additional purification steps lead to an improvement in the overall quality of mass spectra for AmtB.

The trimeric AmtB was expressed as a tobacco etch mosaic virus (TEV) protease cleavable N-terminal fusion to GFP and 6× His-tag (AmtB-GFP). (a) General outline for the purification of membrane protein complexes for native MS. Solubilized AmtB-GFP is first purified by IMAC then concentrated and further purified by gel filtration chromatography. The C-terminal fusion is removed by TEV protease treatment and further purified by reverse IMAC resulting in highly purified membrane protein complexes. (b) Native mass spectra at various time points in the purification process. After IMAC purification (top panel, purple) the ion peaks are broad for the trimeric complex with no disassociation products observed. Post gel filtration (middle panel, green) the ion peaks are improved for the trimeric complex along with disassociation products, monomer and dimer. The final purification step is removal of the C-terminal fusion which results in resolved mass spectra for both the trimeric complex and disassociation complexes (bottom panel, red). In general, we find that removal of the C-terminal fusion leads to more disassociation products.

(iii) Effect of detergent on membrane protein complexes

Membrane protein complexes can be examined in a range of different detergents and the effects on oligomeric state, bound moieties (e.g. lipid), and purity are readily assessed. In addition, the stability of membrane complexes in different detergents over time can be assessed. Instability is inferred when the oligomeric complex is no longer observable in the mass spectrum.

(iv) Lipid binding

One of the interesting observations of this methodology has been the ability to preserve interactions with phospholipids. This discovery was recently highlighted from the MS of intact ATP synthases, where specific phospholipid interactions were maintained and subsequently identified using MS5. This protocol includes a description of how to prepare lipids compatible with the MS of membrane complexes for binding and titration studies. Once these stocks are prepared, membrane protein complexes can be readily screened for their specificity and binding (discussed further in anticipated results). This new development highlights the utility of MS as a powerful technique for understanding the role and importance of membrane protein-lipid interactions.

Before Starting

Focus here has been placed on preparation and analysis of membrane proteins complexes. Readers should however be familiar with the detailed protocols for soluble protein complexes described previously18. In particular, the description how the capillaries are prepared, the processes involved in establishing a stable electrospray, and in calibrating and analyzing mass spectra. In this protocol these areas will be described only in brief. We have designed this protocol to communicate our experience with analyzing challenging membrane protein complexes with the primary goal of highlighting key considerations for researchers to be successful with this new technique.

As a starting point for mass spectrometry of membrane protein complexes we recommend the ammonium channel, particularly AmtB-GFP described herein. In our hands, this membrane protein complex is robust and mass spectra can be collected in many different detergents.

MATERIALS

REAGENTS

Ammonium acetate (greater than 98%; Sigma Aldrich, cat. no. A7262)

7.5 M ammonium acetate solution (Sigma Aldrich, cat. no. A2706)

Cesium Iodide (99.999%; Sigma Aldrich, cat. no. 203033)

Chloroform (ACS spectroscopic grade, > 99.8%; Sigma Aldrich cat. no. 366919) ! CAUTION Chloroform is toxic and flammable

Imidazole (99+%; Fisher Scientific/Acros Organics, cat. no. I/0010/53)

Methanol (CHROMASOLV®, for HPLC, > 99.9%; Sigma Aldrich, cat. no. 34860) ! CAUTION Methanol is toxic and flammable

Sodium chloride (> 99.5%; Sigma Aldrich, cat. no. S7653)

TRIS (Trizma® Base, 99.9%; Sigma Aldrich, cat. no. T1503)

β-Mercaptoethanol (≥ 99.0%; Sigma Aldrich, cat. no. M6250)

EDTA (99.995%; Sigma Aldrich, cat. no. 431788)

Anapoe-58 (Brij-58/C16E20) (Affymetrix, cat. no. APB058)

C8E4 (Tetraethylene Glycol Monooctyl Ether, Anagrade, ≥ 99%; Affymetrix, cat. no. T350)

C8E5 (Pentaethylene Glycol Monooctyl Ether, Anagrade, ≥ 99%; Affymetrix, cat. no. P350)

Anapoe-C12E8 (Affymetrix, cat. no. APO128)

Anapoe-C12E9 (Affymetrix, cat. no. APO129)

Cymal-5 (5-Cyclohexyl-1-Pentyl-β-D-Maltoside, Sol-Grade, ≥ 98%; Affymetrix, cat. no. C325S)

Cymal-6 (6-Cyclohexyl-1-Hexyl-β-D-Maltoside, Sol-Grade, ≥ 98%; Affymetrix, cat. no. C326S)

Decyl Maltose Neopenyl Glycol (Affymetrix, cat. no. NG322)

Octyl Glucose Neopentyl Glycol (Affymetrix, cat. no NG311)

n-Decyl- β -D-maltoside (Sol-Grade, > 97%; Affymetrix, cat. no. D322S)

n-Dodecyl- β -D-maltoside (Sol-Grade, Anatrace, > 98%; Affymetrix, cat. no. D310S)

n-Dodecyl- β -D-thiomaltopyranoside (Anagrade, ≥ 98%; Affymetrix, cat. no. D342)

n-Octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (Sol-Grade, ≥ 97%; Affymetrix, cat. no. O311S)

n-Octyl- β -D-thioglucopyranoside (Anagrade, ≥ 99%; Affymetrix, cat. no. O314)

n-Nonyl- β -D-glucopyranoside (Sol-Grade, ≥ 97%; Affymetrix, cat. no. N324S)

n-Undecyl- β -D-maltoside (Sol-Grade, ≥ 97%; Affymetrix, cat. no U300S)

Triton™ X-100 (BioXtra; Sigma Aldrich, cat. no T9284)

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE) (Powder, > 99%; Avanti, cat. no. 850757P)

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (POPS) (Powder, > 99%; Avanti, cat. no. 840034P)

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (POPA) (Powder, > 99%; Avanti, cat. no. 840857P)

CsI Calibration Solution (see REAGENT SETUP)

Mem Extraction Buffer (see REAGENT SETUP)

Mem Wash Buffer (see REAGENT SETUP)

Mem Elution Buffer (see REAGENT SETUP)

Mem MS Buffer (see REAGENT SETUP)

REAGENT SETUP

CsI Calibration Solution: 100 mg/mL CsI dissolved in water and stored at room temperature.

Chloroform:Methanol solution: dilute 1 volume of methanol into 2 volumes of chloroform. Work-up and store in glassware at room temperature.

Mem Extraction Buffer: 200 mM sodium chloride, 20 mM imidazole, 50 mM TRIS, 1-2% detergent of choice, and pH to 8.0 with hydrochloric acid. See Newby et al 20096 regarding appropriate detergent concentrations for solubilization. See note below regarding buffers containing detergents.

Mem Wash Buffer: 200 mM sodium chloride, 20 mM imidazole, 50 mM TRIS, 2× CMC detergent of choice, and pH to 8.0 with hydrochloric acid at room temperature. See note below regarding buffers containing detergents.

Mem Elution Buffer: 100mM sodium chloride, 250 mM imidazole, 50 mM TRIS, 2× CMC detergent of choice, and pH to 8.0 with hydrochloric acid at room temperature. See note below regarding buffers containing detergents.

Mem MS Buffer: 200 mM ammonium acetate and 2× CMC detergent of choice pH to 7.2 or 8.0 with ammonium hydroxide. See note below regarding buffers containing detergents.

Membrane protein expression and purification: Depending on your target membrane protein complex, purification strategy and expression system, we suggest the following previous protocols 6-8. In general, we express membrane proteins with a tobacco etch mosaic virus (TEV) protease cleavable C-terminal fusion to superfolder green fluorescent protein (GFP)19 followed by a 6× His-tag similarly to that described by Drew et al 20087. The GFP fusion provides visual confirmation of protein expression. In addition, we have also had success with N-terminal tagged membrane proteins. We purify membrane proteins using IMAC, gel filtration, tag removal with a specific protease and end with reverse IMAC. Membrane proteins after IMAC purification are typically of sufficient purity to obtain good quality data, however further purification maybe necessary to obtain a resolved mass spectrum. (Supplementary Methods for more information.)

Buffers containing detergent: We typically make large stocks of each buffer without detergent, filter sterilize, and store at room temperature. These buffer stocks are supplemented prior to use with the detergent of interest to a final concentration of 2× CMC using a 10% stock of detergent. Buffers containing detergent are stored at room temperature for short storage (<1 week) and frozen for long-term storage. Ammonium acetate buffer is stored for up to two weeks.

Detergents: Stocks of detergent are usually made up at 10% (w/v) in water and frozen. In some cases, a 10% stock solution in water is unobtainable due to variable detergent solubility. Notably, detergents are purchased from Anatrace at Sol-grade compared to the higher purity Anagrade since no discernible difference in mass spectra was observed when comparing the two grades of DDM using AmtB-GFP.

EQUIPMENT

In-house Capillaries (These are prepared as previously described 18. See BOX 1 for a summary of the most important considerations)

BOX 1. Capillary Preparation and Considerations.

Preparation •TIMING 1-2 h

Prepare capillaries as described previously18.

Considerations

There are three considerations for capillaries used in nanoES for membrane proteins worth noting:

Filament – The majority of membrane proteins screened in our lab prefer capillaries with filaments, which appears to help the sample wick to the tip of the needle. However, in some cases non-filament needles work just as well.

Length – A general strategy is to start with a long needle and gradually trim back if the spray or ion current is intermittent.

Gold coating – A poor coated needle can lead to intermittent spray. When preparing needles we typically handle them with gloves to avoid oils from hands which will interfere with the coating process.

Boroscilicate glass capillaries (Harvard Apparatus); 1.0 mm OD × 0.5 mm i.d. with filament (cat. no. GC100FS-10) and 1.0 mm OD × 0.58 mm i.d. (cat. no. GC100-10).

Buffer exchange devices, Micro Bio-Spin 6 Chromatography columns, MW exclusion limit 6 kDa (Tris buffer, Bio-Rad, cat. no. 732-6221)

Superdex 200 10/300 GL (GE Healthcare, cat. no. 17-5175-01)

Bio-rad Micro Bio-spin Chromatography columns (Empty; Bio-Rad, cat. no. 732-6204)

Ni-NTA agarose (Sepharose CL-6B support, 50% suspension in 30% ethanol, precharged with Ni2+; Qiagen, cat. no. 30250)

Centrifugal Concentrators, Ultrafree-0.5, MWCO 100kDa (Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Unit with Ultracel-100 membrane; Millipore, cat. no. UFC910024)

Vivaspin 500, PES, 100 kDa MWCO (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. FDP-875-045S)

HisTrap HP 5mL columns (5 × 5 ml; GE Healthcare, cat. no. 17-5248-02)

Glass separator funnel, pear shape (Scientific Glass Laboratories Ltd, cat. no. A128-004HZ-02)

glass vial with screw caps

glass test tubes

Mass spectrometer. In this study we used a Q-TOF 2 instrument (Micromass, Manchester, UK) with a Z-spray source including modifications previously described 20. In brief, modifications include a valve to adjust source pressure and a modified RF unit.

Data Analysis

Data collected using a modified Q-TOF 2 instrument (described in Equipment section) was initially processed and exported with MassLynx software (Waters, UK). Further data analysis was performed using custom in-house software written in Python programming language. In brief, the software includes least squares peak fitting, assignment of masses, charge state envelope fitting, and additional features for visuallizing mass spectra. Software can be obtained upon request.

PROCEDURE

Preparation of purified membrane protein complex •TIMING 20 min – 2 h

1| Membrane protein preparation for native mass spec is achieved by either using a buffer exchange device (option A) or by gel filtration (option B) on a purified membrane protein complex (see BOX 2). Regardless of the option chosen, the final concentration of your membrane protein complex should be, at the minimum, in the high nanomolar range. Typically we begin with option A and use option B if a membrane protein requires an additional purification step.

- Buffer Exchange Centrifugal Devices.

- Follow manufacturer’s protocol for the buffer exchange centrifugal device and exchange into Mem MS Buffer.

- Gel Filtration

- Equilibrate a small gel filtration column, such as a Superdex 200 column, in Mem MS Buffer.

- Inject the membrane protein sample onto the column.

- Peak fractions containing the membrane protein complex can directly be used for analysis.

BOX 2. Membrane Protein Detergent Screen.

Here we outline a general protocol for screening the effect of differing detergents on the membrane protein complex of interest containing a His-tag starting from either a purified membrane protein complex or membranes prepared as described by Newby et al 20096. Briefly, the membrane protein complex is either extracted directly from membranes into the detergent to be screened or purified protein-detergent complex is exchanged from one detergent to the one to be screened. Screening detergents can lead to the identification of detergents which improve mass spectral resolution and lower activation energy requirements.

Membrane Protein Preparation •TIMING 2 – 24 h

Decide what detergents you want to screen for your membrane protein complex, for example from those listed in Table 1. For each detergent, prepare separately Mem Extraction Buffer, Mem Wash Buffer, Mem Elution Buffer, and Mem MS Buffer containing detergent at the appropriate concentration (see Reagent Setup).

- Decide whether you want to start from prepared membranes or a purified membrane protein complex Aliquot material for each detergent chosen in Step 1 following the appropriate option below.

- Prepared membranes

- Dilute an aliquot of membrane protein suspension into Mem Extraction Buffer containing the desired detergent.

- Incubate for 1 hour to overnight at 4 °C.

- Purified membrane protein

- Add 30-50 μL of purified protein to 500 μL of Mem Extraction Buffer containing the desired detergent.

- Incubate for 30 min to 1 hour to facilitate detergent exchange.

IMAC Purification and Concentration •TIMING 4 – 6 h

3. Prepare one column per detergent chosen. Aliquot 400 μL of Ni-NTA agarose bead slurry to 1 ml Bio-Rad centrifuge column.

4. Briefly centrifuge at 0.1g to pack the bead slurry.

5. Wash the settled beads with 500 μL of water and briefly centrifuge at 0.1g.

6. Repeat step 4 twice.

7. Wash with 500 μL of Mem Elute Buffer.

▲CRITICAL STEP At this point the column should drip due to the presence of detergent in the buffer, if not briefly centrifuge at 0.1g.

8. Wash two times with 500 μL of Mem Wash Buffer.

9. Wash once with 500 μL of Mem Extraction Buffer.

10. Bind solubilized or extracted membrane protein from step 1 above by adding to the settled beads. Allow sample to drip through the column.

▲CRITICAL STEP Do not to disturb the settled beads.

11. Wash five times with 500 μL of Mem Wash Buffer.

12. Elute protein with 500 μL of Mem Elution Buffer. Add drop-wise to the center of the beads and collect the eluent. Note if your protein is tagged with GFP, binding and elution can be monitored by ultraviolet light.

13. Concentrate the eluted membrane protein with an 100 kDa MWCO or suitable concentrator at 13,000g down to 60-100 μL (typical centrifuge time being 2 to 2.5 minutes)

▲CRITICAL STEP Care must be taken when selecting the MWCO of the concentrator as detergent micelles can unexpectedly concentrate in addition to the membrane protein16.

14. Concentrated membrane protein can now be prepared for native MS, see main protocol.

▲CRITICAL STEP All buffers should contain detergent. Do not freeze buffer exchanged membrane protein in Mem MS Buffer. Freezing or omitting detergent can result in aggregation of membrane protein samples.

Buffer exchanged membrane protein should be stored on ice or at 4 °C.

■PAUSE POINT Buffer exchanged samples can typically be stored at 4 °C for up to one week. Importantly, in some cases the stability of the preparation can be as short as the day of the preparation.

Initial preparation of mass spectrometer •TIMING 10 min

3| Adjust several mass spectrometer parameters to the following suggested starting conditions for membrane protein complexes:

| collision gas pressure | 0.3 MPa |

| backing pressure | 6.0 |abar |

| cone voltage | 180 V |

| collision energy | 195 V |

| capillary voltage | 1.5-1.9 kV |

| collision gas | Argon |

Alternatively, low energy conditions can be used initially, similarly to those required for soluble protein complexes18. Under these energy conditions, the spectrum will appear extremely heterogeneous, with broad peaks corresponding to micelles and membrane protein-detergent complexes.

Nanoflow ES and optimizing mass spectrometer parameters •TIMING 30 – 90 min

<CRITICAL> Nanoflow electrospray is initiated essentially as previously described18,21, however we provide a brief outline of a similar protocol (also see BOX 1).

4| Load a gold coated capillary into the capillary holder and tighten into position.

! CAUTION Glass capillaries are sharp and fragile.

5| Using a microscope, trim the tip of the capillary with tweezers.

6| Load the capillary with 1-2 μL of prepared membrane protein complex solution with a gel loading tip.

7| Place onto the stage of the electrospray source and apply nanoflow pressure until the loaded solution forms a drop at the capillary tip then remove nanoflow pressure.

▲CRITICAL STEP Nanoflow pressure can be used to maintain nanospray, but best spectra are usually achieved with no nanoflow pressure. Importantly, high nanoflow pressures can be detrimental to spectra quality.

8| Slide the stage into position. As a starting point, adjust the capillary position to be level with the height of the source inlet then move the capillary tip to be roughly 2 cm in distance following an imaginary line at a 45° angle from the normal of the source inlet.

9| Start data acquisition and monitor ion current. Perform fine capillary adjustments to achieve stable ion current.

10| Optimization of the mass spectrometer parameters will depend on the outcome of your mass spectrum (see Figure 3). The starting conditions, listed in step 3, are near the limit of activation energy – cone and collision voltages – of commercial instrumentation. Therefore, activation energy can be decreased or increased iteratively by adjusting parameters depending on what the mass spectrum looks like (refer to Figure 3) following the steps in options A, B or C.

- Mainly monomer and/or disassociation products – excessive activation energy or poor transmission of higher mass species.

- Lower the activation energy by lowering both cone and collision energy voltages, for example by 10 V.

- If lowering activation energy doesn’t lead to resolved or broad peak(s), make slight incremental adjustments in source and/or collision pressure to improve transmission of higher mass species.

- Poorly resolved or broad peak(s) – insufficient collisional activation.

- Try increasing activation by one of the following: Increase cone and/or collision voltage.

- Lower or raise collision gas pressure.

- Lower the source pressure of the instrument.

- Change the collision gas from Argon to a larger inert gas, such as SF6.

- Well-resolved peaks for the membrane protein complex.

- No need for further optimization.

Lipid binding studies •TIMING 30 – 90 min

11| Prepare several titrations of lipid stock (see BOX 3), for example in the range of 250 ng/μL to 100 μg/mL, in Mem MS Buffer.

BOX 3. Preparation of Stock Solutions of Lipids.

Lipid stocks are prepared in Mem MS Buffer, containing the detergent of interest, and used for subsequent titration with MS prepared membrane protein samples. The choice of detergent for lipid binding studies may affect the amount of bound lipid.

•TIMING 1-2 d

-

Weigh out lipid powder and dissolve in chloroform:methanol solution to a final concentration of 10 mg/mL.

▲CRITICAL STEP Dissolve lipid powders and store subsequent mixtures containing organic solvents in glassware.

! CAUTION Chloroform and methanol are both toxic and flammable.

Transfer the dissolved lipid mixture into a glass separator funnel, or glass vial with screw cap.

Add water to reach 20% of the final volume (e.g. 1 mL water to 4 mL dissolved lipid mixture).

Shake the solution and allow phases to separate.

Repeat step 4 two times.

-

(Optional) Lipids can be acidified to remove up to 50-90% of sodium adducts (data not shown). To do this, add hydrochloric acid to the upper aqueous phase drop wise until pH is around 3.0 ▲CRITICAL STEP At high pH the phosphate groups will be protonated.

! CAUTION Hydrochloric acid is corrosive.

Shake the solution and allow phases to separate.

Repeat step 7 two times.

-

Transfer the lower organic phase containing lipid to a glass vial.

▲CRITICAL STEP Measure and record the weight of the glass vial before addition of lower organic phase.

Lyophilize the sample overnight by placing preferably into a SpeedVac or a rotatory evaporator. An inert gas stream, such as Argon or Nitrogen, can also be used to remove the organic solvents but the dried lipid film may contain residual chloroform.

Determine the weight of the dried lipid film by subtracting the measured weight from the recorded value from step 7.

Add Mem MS Buffer to the lipid film such that the final concentration of lipid is in the range of 2.5 to 5 mg/mL.

Resuspend the lipid film using a water sonicator bath for 10-30 minutes. The solution may become cloudy due to vesicle formation.

-

The final lipid suspension can now be used as a concentrated stock for preparing diluted lipid stocks for membrane protein-lipid binding studies.

■PAUSE POINT Lipid stocks can be stored at −20 °C.

▲CRITICAL STEP Avoid using lipid stocks dissolved in organic solvents, such as chloroform, as they are denaturants and may alter protein-lipid binding interactions (see Supplementary Figure 3).

12| Mix thoroughly equal volumes of membrane protein preparation with titrated lipid stock and incubate at desired temperature for a minimum of 10 minutes.

▲CRITICAL STEP Note the final concentration of lipid and protein will be diluted by half.

■PAUSE POINT Samples can be stored at 4 °C overnight prior to analysis.

13| Analyze equilibrated membrane protein and lipid preparations.

Calibration and data processing

14| Calibrate the instrument/spectra using CsI solution and analyze spectra as described previously 18.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

Troubleshooting advice can be found in Table 2.

Table 2. Troubleshooting table. [As far as possible, please include the step number(s) at which the problem first becomes evident.].

| Step | Problem | Possible Reason | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Protein precipitates either on-the column or in solution | Incorrect pH | The pH is not ideal for sample. Try using Mem MS Buffer at pH 8.0, or other pH values. |

| Incompatible detergent | The membrane protein is not soluble in this detergent. Choose a different MS-compatible detergent from table 1. | ||

|

| |||

| 9 | Intermittent spray or fluctuating ion current | Capillary blocked or narrow tip diameter | Trim back the capillary tip with tweezers. |

| Protein too concentrated | High protein concentrations tend to form viscous solutions making it difficult for nanospray. Dilute the sample in Mem MS Buffer. | ||

| Tip incorrectly trimmed | Ensure the capillary tip is smooth and not jagged. If so, either trim back the tip with tweezers or smoothen by pushing the tweezers against the tip. | ||

|

| |||

| 9 | Loss of spray or ion current | Sample aggregated | See problem ‘Protein crashed out…’ above. |

| Gold coating stripped off the tip of the capillary | Trim back the capillary tip with tweezers. | ||

| Cone covered in detergent solution | Remove and clean the cone. | ||

|

| |||

| 10 | Broad peak(s) and/or excessive adducts as seen in mass spectrum | Sample contains impurities and/or excess detergent, salts, and/or lipids | Prepare membrane protein sample by gel filtration to increase purity and/or remove adducts (step 1B). If problem remain try a detergent screen (BOX 2). |

|

| |||

| 10 | Ion series offset by regular interval | High concentration of detergent in sample leading to mass spectra of detergent micelles. | Dilute sample into Mem MS Buffer in the absence of detergent to dilute detergent. |

|

| |||

| 10 | Charge state series is complicated | Detergent choice affecting ionization and/or producing detergent clusters | Find another detergent using the detergent screen described in BOX 2. Alter the activation energy to remove detergent from the membrane protein complex and to disrupt detergent clusters (see Figure 3) |

|

| |||

| 13 | No lipid bound during lipid titration | Chloroform present in solution | Prepare lipid stocks as described in BOX 3 with added care and patience in organics removal step |

| Low concentration of lipid to protein | Perform higher titration series. Try another lipid type; lipid binding will be protein dependent with potential for no lipid binding. | ||

| Detergent used is not competed off by lipid | Perform detergent screen as described in BOX 2 and attempt lipid binding studies thereafter. | ||

|

| |||

| 13 | Broad hump seen during lipid binding studies | High concentration of lipid to protein | Perform titration series at a lower concentration of lipids. |

ANTICIPATED RESULTS

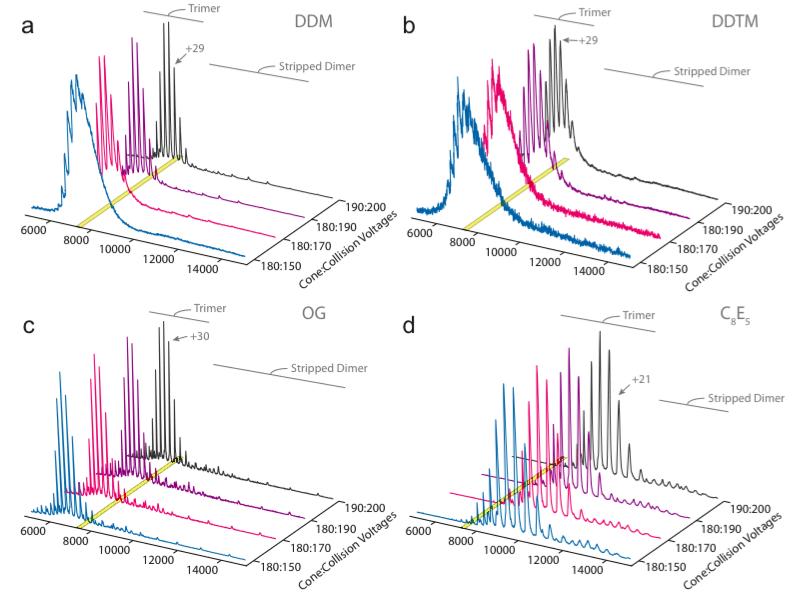

As an example of the detergent screening protocol, we applied this methodology to AmtB-GFP purified in DDM which required a collision energy voltage of 170V to obtain reasonable mass spectra (Figure 6a). After screening MS-compatible detergents (Table 1), some detergents can increase or decrease the activation energy to obtain comparable spectra. Small changes in detergent chemistry can vary the activation energy requirements, for example alteration in the linkage between the sugar and alkyl chain from Oxygen in DDM to Sulfur in DDTM (Figure 6b). Interestingly, detergents with higher CMC values compared to DDM have produced high quality mass spectra. An example of this is OG which has a ~61-fold higher CMC value compared to DDM, but required much lower activation energy (Figure 6c). Interestingly, polyoxyethylene glycol detergents overall resulted in a reduction in the average charge state of the membrane protein complex (Figure 6d). The origin of this change in charge state is presently unclear but may be the result of altered solvent accessible area or altered solution properties.

Figure 6. Mass spectra activation series for selected detergents from a detergent screen on AmtB-GFP.

Purified AmtB-GFP in DDM was used as the starting material in a detergent screen (see Figure 1b and BOX 2) to find detergents that improve mass spectra quality. The trimer and stripped dimer regions of the mass spectrum are shown as a function of activation energy – increasing cone and collision voltages. The yellow shaded region highlights the peak for the +29 charge state of the AmtB-GFP trimeric complex. (a) AmtB-GFP detergent exchanged into DDM, serving as the control in this experiment, highlights the activation energy required to emerge the membrane protein from the DDM micelle. (b) Detergent exchange into DDTM resulted in broad peaks and increased activation energy, similarly to several other detergents. (c) AmtB-GFP exchanged into OG produced well-resolved mass spectra even at the lowest activation energy comparable to the highest activation energy for DDM. (d) C8E5, a polyoxyethylene glycol detergent, reduced the average charge state of the trimeric complex similarly to others within this detergent family (Table 2). Notice that the trimeric complex has shifted from one centered at 7,000 m/z to 9,500 m/z corresponding roughly to a charge state reduction of eight. A detergent screen can be useful when trying to improve and/or lower the activation energy to obtain resolved mass spectra of membrane proteins.

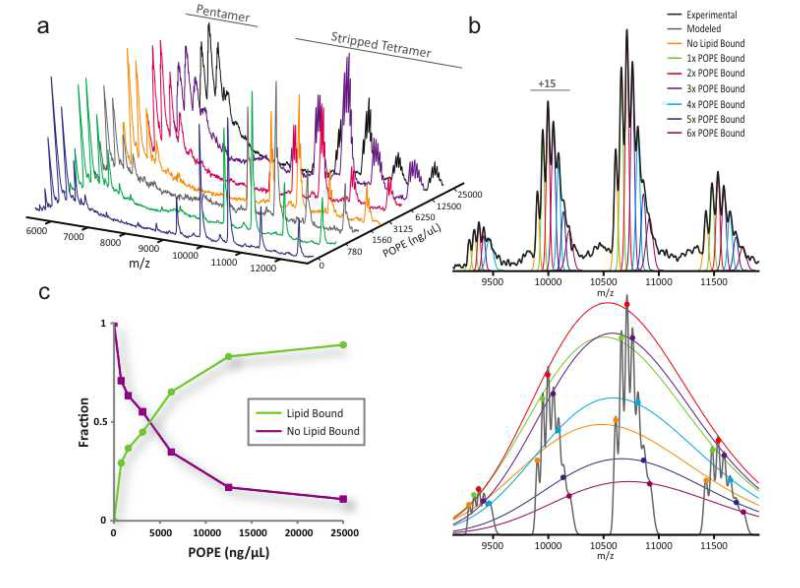

Once the MS conditions have been optimized for a membrane protein complex, small molecule and/or lipid binding can be evaluated using MS. We have found that a variety of phospholipids bind to membrane proteins with some displaying more specificity over others. In addition, lipids can be titrated and incubated with membrane protein complexes and analyzed under the appropriate MS conditions. For example, we expressed and purified a ligand-gated ion channel from Erwinia chrysanthemi (ELIC) and screened for lipid binding. The crystal structure of ELIC reveals a pentameric channel 22,23. We observe variable lipid binding for ELIC when incubated with a titration series of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE) (Figure 7a). In this example, lipid binding to the pentamer concomitantly resulted in peak broadening whereas in the stripped tetramer region individual lipid bound states are resolved, making this region more suitable for data analysis. Data analysis of the stripped tetramer region entails modeling individual peaks and using this information to model charge state envelopes for individual lipid bound states (Figure 7b). The fitted charge state envelopes are good reporters of the relative abundance of a given bound state as it takes into account all of the experimental peaks. Equilibrium binding curves can be generated by plotting the total lipid bound against lipid concentration (Figure 7c). It is worth mentioning at this point, that mass spectrometry is not a directly quantitative technique, in that the signal intensities generated are not proportional to the concentration of the protiens/lipids in solution due to variances in physiochemical properties, ionization efficiency, transmission and detector response. This said, the use of labeling techniques and internal standards has made the technique extremely valuable in areas such as quatitative proteomics 24.

Figure 7. Monitoring phsopholipid binding and stoichiometry.

ELIC, a pentameric membrane protein complex, titrated with solutions of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE) prepared as described in BOX 3 and incubated at room temperature prior to measurement. (a) Mass spectra series of ELIC equilibrated with increasing concentrations of POPE. Shown are the pentamer and stripped tetramer regions of the mass spectrum. Peak broadening of the ELIC pentamer ion series (6,000 to 7,500 m/z) occurs with increasing concentrations of lipid. In contrast, ion series are resolved for various POPE bound states in the stripped tetramer region (8,000 to 13,000 m/z). (b) Data analysis of the resolved lipid bound states within the stripped tetramer region of the mass spectrum from ELIC incubated with 25 μg/mL of POPE. Multiple Gaussian peaks were modeled using least squares regression for various lipid bound states for each individual charge state to the experimental data (top panel). Peak centers and height values from these modeled Gaussian peaks are then extracted and fitted with a charge state envelope for individual lipid bound states (bottom panel). The resulting values for the fitted charge state envelopes reflect the fraction of various lipid bound states within the mass spectrum. (c) Plot of the fraction ELIC unbound and sum of ELIC bound to lipid.

Several factors can influence the amount of lipid bound to membrane protein samples. The concentration of detergent in the membrane protein sample can alter binding. We have found that at a given concentration of lipid, binding is influenced by detergent concentration with more lipid binding observed at 1× CMC compared to 2× CMC of detergent. Preparation of lipid stock is important and we outline a general protocol to follow for lipid binding experiments. Titrating directly from lipid stocks dissolved in organic solvents, such as chloroform, should be avoided as this significantly alters the amount of lipid bound and can potentially denature the membrane protein (Supplementary Figure 3). In some cases, we observe that lipid binding increases over time and should be monitored. In addition temperature should be controlled. These factors have to be taken into careful consideration, such as when extracting binding constants from equilibrium data.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Professor R. Dutzler and Iwan Zimmerman for the ELIC expression plasmid, Professor Douglas Rees and Dr. Chris Gandhi for the OCAM constructs. The Medical Research Council (MRC), ERC IMPRESS and Wellcome Trust are acknowledged for funding. AL is a Nicholas Kurti Junior Research Fellow of Brasenose College, Oxford. CVR is a Royal Society Professor.

Footnotes

Competing Financial Interests

University of Oxford has filed a provisional patent on mass spectrometry mediated drug discovery for membrane proteins using polyoxyethylene glycol detergents.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dorsam RT, Gutkind JS. G-protein-coupled receptors and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:79–94. doi: 10.1038/nrc2069. doi:10.1038/nrc2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lappano R, Maggiolini M. G protein-coupled receptors: novel targets for drug discovery in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:47–60. doi: 10.1038/nrd3320. doi:10.1038/nrd3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrera NP, Di Bartolo N, Booth PJ, Robinson CV. Micelles protect membrane complexes from solution to vacuum. Science. 2008;321:243–246. doi: 10.1126/science.1159292. doi:10.1126/science.1159292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrera NP, Robinson CV. Advances in the mass spectrometry of membrane proteins: from individual proteins to intact complexes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:247–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062309-093307. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-062309-093307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou M, et al. Mass spectrometry of intact V-type ATPases reveals bound lipids and the effects of nucleotide binding. Science. 2011;334:380–385. doi: 10.1126/science.1210148. doi:10.1126/science.1210148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newby ZE, et al. A general protocol for the crystallization of membrane proteins for X-ray structural investigation. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:619–637. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.27. doi:10.1038/nprot.2009.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drew D, Lerch M, Kunji E, Slotboom DJ, de Gier JW. Optimization of membrane protein overexpression and purification using GFP fusions. Nat Methods. 2006;3:303–313. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0406-303. doi:10.1038/nmeth0406-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drew D, et al. GFP-based optimization scheme for the overexpression and purification of eukaryotic membrane proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:784–798. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.44. doi:10.1038/nprot.2008.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sonoda Y, et al. Benchmarking membrane protein detergent stability for improving throughput of high-resolution X-ray structures. Structure. 2011;19:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.12.001. doi:10.1016/j.str.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seddon AM, Curnow P, Booth PJ. Membrane proteins, lipids and detergents: not just a soap opera. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1666:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jurchen JC, Williams ER. Origin of asymmetric charge partitioning in the dissociation of gas-phase protein homodimers. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:2817–2826. doi: 10.1021/ja0211508. doi:10.1021/ja0211508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Light-Wahl KJ, Schwartz BL, Smith RD. Observation of the Noncovalent Quaternary Associations of Proteins by Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1994;116:5271–5278. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)85034-8. doi:10.1021/ja00091a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benesch JL, Robinson CV. Mass spectrometry of macromolecular assemblies: preservation and dissociation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruotolo BT, Benesch JL, Sandercock AM, Hyung SJ, Robinson CV. Ion mobility-mass spectrometry analysis of large protein complexes. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1139–1152. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.78. doi:10.1038/nprot.2008.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang SC, et al. Ion mobility mass spectrometry of two tetrameric membrane protein complexes reveals compact structures and differences in stability and packing. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15468–15470. doi: 10.1021/ja104312e. , doi:10.1021/ja104312e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strop P, Brunger AT. Refractive index-based determination of detergent concentration and its application to the study of membrane proteins. Protein Sci. 2005;14:2207–2211. doi: 10.1110/ps.051543805. doi:10.1110/ps.051543805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khademi S, et al. Mechanism of ammonia transport by Amt/MEP/Rh: structure of AmtB at 1.35 A. Science. 2004;305:1587–1594. doi: 10.1126/science.1101952. doi:10.1126/science.1101952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez H, Robinson CV. Determining the stoichiometry and interactions of macromolecular assemblies from mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:715–726. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.73. doi:10.1038/nprot.2007.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pedelacq JD, Cabantous S, Tran T, Terwilliger TC, Waldo GS. Engineering and characterization of a superfolder green fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:79–88. doi: 10.1038/nbt1172. doi:10.1038/nbt1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sobott F, Hernandez H, McCammon MG, Tito MA, Robinson CV. A tandem mass spectrometer for improved transmission and analysis of large macromolecular assemblies. Anal Chem. 2002;74:1402–1407. doi: 10.1021/ac0110552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirshenbaum N, Michaelevski I, Sharon M. Analyzing large protein complexes by structural mass spectrometry. J Vis Exp. 2010 doi: 10.3791/1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hilf RJ, Dutzler R. X-ray structure of a prokaryotic pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature. 2008;452:375–379. doi: 10.1038/nature06717. doi:10.1038/nature06717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hilf RJ, et al. Structural basis of open channel block in a prokaryotic pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1330–1336. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1933. doi:10.1038/nsmb.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bantscheff M, Schirle M, Sweetman G, Rick J, Kuster B. Quantitative mass spectrometry in proteomics: a critical review. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;389:1017–1031. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1486-6. doi:10.1007/s00216-007-1486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.