Abstract

Using an identification task, we examined lexical effects on the perception of vowel duration as a cue to final consonant voicing in 12 children with specific language impairment (SLI) and 13 age-matched (6;6–9;6) peers with typical language development (TLD). Naturally recorded CV/t/sets [word–word (WW), nonword–nonword (NN), word–nonword (WN) and nonword–word (NW)] were edited to create four 12-step continua. Both groups used duration as an identification cue but it was a weaker cue for children with SLI. For NN, WN and NW continua, children with SLI demonstrated certainty at shorter vowel durations than their TLD peers. Except for the WN continuum, children with SLI demonstrated category boundaries at shorter vowel durations. Both groups exhibited lexical effects, but they were stronger in the SLI group. Performance on the WW continuum indicated adequate perception of fine-grained duration differences. Strong lexical effects indicated reliance on familiar words in speech perception.

Keywords: specific language impairment, speech perception, lexicon, categorical perception

Introduction

Over 30 years of research has described speech perception deficits in children with specific language impairment (SLI), particularly on tasks that require identification of minimally distinct speech sounds (Elliot & Hammer, 1988; Evans, Viele, Kass, & Tang, 2002; Frumkin & Rapin, 1980; Hayiou-Thomas, Bishop, & Plunkett, 2004; Leonard, McGregor, & Allen, 1992; Stark & Heinz, 1996; Tallal & Stark, 1981; Tallal, Stark, Kallman, & Mellits, 1980). The precise nature of these deficits and their relationship to the more general language deficits observed in these children remains controversial (Bradlow et al., 1999; Coady, Evans, Mainela-Arnold, & Kluender, 2007; Rosen, 2003; Sussman, 1993). One view is that children with SLI have deficits in processing temporal features (e.g. duration) or deficits in temporal processing (i.e. processing acoustic features that are brief or rapidly changing). Among the controversies regarding this view are whether speech perception deficits are limited to temporal aspects of perception, whether perceptual deficits differentiate children with SLI from their typically developing peers, and how these deficits impact other language domains.

Auditory perception and processing deficits

This auditory processing view has been supported by findings of impairments in perception of temporal features and features that are temporally brief or are presented rapidly (e.g. transition duration, vowel duration, stop gaps: Elliot & Hammer, 1988; Frumkin & Rapin, 1980; Stark & Heinz, 1996; Tallal, 1976; Tallal & Stark, 1981; Tallal et al., 1980). More recently, frequency discrimination deficits have also been identified (Hill, Hogben, & Bishop, 2005; McArthur & Bishop, 2004). However, deficits that occur in some adolescents with grammatical SLI are equally likely to occur in children without SLI (Rosen, Adlard, & van der Lely, 2009).

Auditory temporal processing deficits have been described in a variety of paired temporally distinct minimal speech sounds. Speech sound features that are brief, rapidly changing, delivered at a rapid rate, or have fine-grained duration differences were the basis for identification errors children with SLI made when responding to categorization or discrimination tasks (Elliot & Hammer, 1988; Tallal, Miller, & Fitch, 1993). Vowel pairs (e.g. /ε/-/I/), consonant–vowel syllable pairs (e.g. /ba/, /da/) and stressed and unstressed multi-syllable pairs (e.g. /dabida/, /dabuda/) differing by transition duration, inter-stimulus intervals, and vowel steady state durations have revealed temporal impairments (Bradlow et al., 1999; Burlingame, Sussman, Gillam, & Hay, 2005; Elliott & Hammer, 1988; Frumkin & Rapin, 1980; Leonard et al., 1992; McArthur & Bishop, 2004; Shafer, Ponton, Datta, Morr, & Schwartz, 2007; Stark & Heinz, 1996; Tallal & Stark, 1981; Tallal et al., 1980). The relative duration of neighboring segments and syllables (Leonard et al., 1992; Tallal & Piercy, 1975) also appears to affect identification accuracy. Despite this evidence, the characterization of these deficits as reflecting auditory temporal perceptual deficits rather than poor perceptual performance on difficult contrasts or deficits in higher level linguistic cognitive abilities remains controversial.

Vowel studies have reported adequate perception of long vowels (i.e. 250 ms) and poor perception of shorter vowels (Frumkin & Rapin, 1980; Tallal & Piercy, 1975; Tallal & Stark, 1981). Although the identification of short vowels (i.e. 40–100 ms) has yielded some variable results, two event-related potential and behavioral studies comparing vowels with durations of 50 and 250 ms (Shafer, Morr, Datta, Kurtzberg, & Schwartz, 2005), confirmed poor identification of phonetically similar vowels regardless of duration, but better discrimination of long vowels. For both vowel durations, there was evidence of a late negativity for the children with SLI, indicating discrimination of the speech sounds, but this discrimination occurred in a later time frame than for the children with typical language development (TLD). Similar to Bradlow et al. (1999), only 250 ms vowels yielded robust mismatch negativities in children with SLI (Datta, Shafer, Morr, Kurtzberg, & Schwartz, 2010) demonstrating more typical perception of longer vowels.

Cognitive-linguistic deficits

An alternative to the auditory perception deficit proposal is the view that speech perception deficits in children with SLI reflect, or at least interact with, cognitive–linguistic impairments (e.g. phonological aspects of representation such as category boundaries, lexical representation, attention; attentional control; or working memory). One proposal posited that poor perception of morphemes with low phonetic substance (e.g. brief, low intensity, etc.) requires greater allocation of processing resources to morphosyntactic learning for children with SLI (Leonard, 1989, 1998). Extensive cross-linguistic evidence generally supports this proposal. A more general proposal (Marinis, 2011) suggests that the core deficit in SLI lies in the integration of information at the interface of language components (Jakubowicz, 2003). Support for this notion comes from a finding that children at risk for SLI exhibit early auditory perceptual deficits with a specific effect on prosody. Later in development, these deficits can no longer be readily detected, but what remains are the varied deficits characteristic of SLI. Such proposals fall into a class of explanations that attribute perceptual deficits and their impact to cognitive– linguistic impairments (e.g. phonological aspects of representation such as category boundaries, lexical representation, attention; attentional control, or working memory).

The cognitive–linguistic view posits that the identification problem lies, not just in acoustic processing, but rather, in higher level categorization. According to this view, acoustic features are unimpaired. Instead, these children may have different phoneme boundaries or boundaries that are not as sharp because of greater uncertainty. This atypical category formation may be due to linguistic factors or language-related cognitive abilities affecting speech perception, lexical access or sentence processing such as memory (Marton & Schwartz, 2003), resource capacity (Leonard, 1989; Leonard et al., 1992) and attention (Shafer et al., 2007). According to this view, children with SLI suffer atypical and delayed language acquisition as a result of deficits in higher order linguistic processing. Proponents of both auditory and cognitive–linguistic views agree that poor phoneme recognition may cause children with SLI to be vulnerable to a host of language, learning and reading problems. But the direct links between speech perception and these abilities remain undetermined.

Vowel duration and final consonant voicing

One aspect of English that depends directly on children’s perception of vowel duration is the voicing of final consonants. When the voice bar is removed from final stop consonants, short vowels cue voiceless consonants (e.g. /t/ in feet), and long vowels cue voiced consonants (e.g. /d/ in feed). This perceptual effect occurs in adults (Raphael, 1972) and in typically developing children (Greenlee, 1980; Krause, 1982); however, vowel duration is not as well established as a perceptual cue in children as it is in adults (Nittrouer & Lowenstein, 2007). To date, no study has examined the abilities of children with SLI to use this durational cue to final consonant voicing in word contexts, which may entail perceptual, phonological and lexical knowledge.

Lexical effects in speech perception

In adults, the relation between perception and lexical knowledge has been examined using lexical decision and identification tasks with word–nonword (WN) continua (e.g. dice–tice; dype–type; Ganong, 1980). For the ambiguous stimuli along the category boundaries, subjects were more likely to indicate that they heard the real word rather than the nonword (e.g. dash was more likely than tash and tuft was more likely than duft), thus exhibiting a lexical effect This Ganong Effect (i.e. a bias toward perceiving a real word) has been demonstrated in lexical decision studies (Connine & Clifton, 1987; Fox, 1984) and in a phonetic categorization study (Burton, Baum, & Blumstein, 1989) in which the characteristics of the initial consonants were the distinguishing features. Burton et al. (1989) used two identification tasks with 12-step continua (i.e. duke–tuke and doot–toot) in which voice onset times were the distinguishing features. The lexical effect was present only when the stimuli were more natural and of better quality.

Although most speech perception studies of children with SLI have focused on non-meaningful syllables (nonwords), word contexts add important information and may provide a clearer picture of how speech sound perception relates to lexical representation and processing. In a series of tasks involving categorical perception of words (e.g. bowl/pole) and nonword syllables (/ba/, /pa/), children with SLI exhibited poorer discrimination and identification than their typically developing peers for words and for nonword syllables, whether they were synthetic or natural (Coady et al., 2007). Children with SLI performed comparably to their typically developing peers in their identification of digitally edited words when task memory load was minimized, but still somewhat more poorly in discrimination (Coady, Kluender, & Evans, 2005; Coady et al., 2007).

Summary and purpose

Although it seems likely that lexical effects occur in children, this phenomenon has not been examined in children with or without language impairment. We do not know whether children with typical development will be more or less influenced by their mental lexicon when stimuli are ambiguous (i.e. stimuli surrounding the phoneme boundary). We also do not know whether children with SLI will exhibit lexical effects similar to their peers with TLD. The present study extended the examination of temporal speech perception in children by determining the effects of word status on auditory temporal speech perception for children with and without SLI and by investigating the use of vowel duration as a cue to final consonant voicing. We expected children with TLD to use vowel duration as a cue to final consonant voicing characteristic for all continua and to exhibit lexical effects. For children with SLI, we expected deficits in the use of vowel duration as a cue and atypical lexical effects because of a limitation in the ability to use phonological information in this task. However, the direction of the deficits (i.e. stronger vs. weaker lexical effect) for SLI was unknown. If children with SLI exhibit stronger lexical effects than their typically developing peers it would suggest that lexical information drives their identification decisions and may reflect weaker perceptual abilities. If children with SLI exhibit weaker lexical effects it would suggest that their lexical knowledge for these items is less well established and they rely more on their perception of this English-specific vowel duration distinction. These findings may be helpful in elucidating the role of stored lexical representations for spoken word recognition and vocabulary learning. Group differences in lexical effect (i.e. SLI vs. TLD) may be related to the slow vocabulary growth observed in children with SLI.

Method

Participants

Twenty-six monolingual English-speaking children, ages 6;6–9;9, were recruited. Twelve of the children were diagnosed with SLI, one had LI (because of a low nonverbal IQ – see below) and 13 had TLD. One child with SLI was later excluded because of an inability to complete training. The children were pair-wise age-matched within 3 months across the two groups (MSLI = 7;7, SDSLI = 0;9); (MTLD = 7;7, SDTLD = 1;0); t (23) = 0.012, p > 0.05. All the children resided in the New York City metropolitan area. Parents completed written questionnaires that included information about their educational, vocational, language and ethnic backgrounds, and their children’s academic, medical and social–emotional histories.

All of the children were examined by the second author, a clinically certified speech-language pathologist, or by a research assistant, who was completing her clinical fellowship for certification. The examiners administered two standardized tests, a hearing screening and the experimental task to all children.

General inclusion criteria

All the children were monolingual, and had intelligible conversational speech with no apparent expressive phonological impairments. All had unremarkable physical, neurological and social–emotional histories.

Each child also passed a pure tone screening at 20 dB HL for 500, 1000 and 2000 Hz (American Speech–Language–Hearing Association, 1990). They each had normal tympanograms bilaterally defined by peak compliance of 0.2–1.4 cm3/ml, tympanic peak pressure between −150 and 100 daPa, and tympanogram gradient between 60 and 150 daPa (American Speech–Language– Hearing Association, 1990).

All but one child had a performance IQ within normal limits on The Test of Nonverbal Intelligence – 3rd edition (TONI-3: Brown, Sherbenou, & Johnsen, 1997). The average standard scores for the SLI group were 92.2 (SD = 10.0) and for the TLD group the mean was 99.3 (SD = 10.1). The youngest child in the SLI group (6;6) scored a 75. This child’s data were ultimately included in the SLI group, because her performance was consistent with the group data (for the 11 children with SLI) for language testing and experimental task performance.

Group identification

Children in the SLI group, nine males and three females, were diagnosed with language impairment and were currently receiving services from a speech-language pathologist. Data are not reported for the one child who could not complete the training portion of the experiment. Each child with SLI also scored below 85 (i.e. more than −1 SD) on one or more composite scores of the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals: Third Edition (see Table 1; CELF-3: Semel, Wiig, & Secord, 1995). Eight of the children had low expressive scores, one had a low receptive score, and three had low receptive and expressive scores. The children included in the TLD group, seven males and six females, reportedly had age-appropriate grade and reading levels, no history of speech or language impairments, and, as shown in Table 1, composite scores were within the normal range on the CELF-3 (Semel et al., 1995).

Table 1.

Group demographics and standard scores.

| SLI |

CELF-3a |

||||

| Age | Gender | TONI-3b | RLSc | ELSd | TLSe |

| 6;6 | M | 75 | 94 | 65 | 78 |

| 6;7 | F | 107 | 92 | 78 | 84 |

| 6;7 | M | 87 | 84 | 78 | 80 |

| 6;11 | M | 85 | 84 | 90 | 86 |

| 7;2 | F | 81 | 75 | 82 | 77 |

| 7;5 | M | 97 | 94 | 75 | 83 |

| 7;9 | F | 95 | 69 | 53 | 59 |

| 8;1 | M | 95 | 88 | 78 | 82 |

| 8;4 | M | 95 | 94 | 78 | 85 |

| 8;8 | M | 110 | 90 | 82 | 85 |

| 8;9 | M | 89 | 104 | 78 | 90 |

| 9;6 | M | 90 | 92 | 75 | 82 |

| TLD |

CELF-3a |

||||

| Age | Gender | TONI-3b | RLSc | ELSd | TLSe |

| 6;6 | F | 89 | 110 | 120 | 115 |

| 6;8 | F | 102 | 108 | 96 | 102 |

| 6;8 | M | 100 | 100 | 96 | 97 |

| 6;11 | M | 117 | 116 | 116 | 116 |

| 7;1 | M | 100 | 108 | 108 | 108 |

| 7;2 | F | 100 | 104 | 108 | 106 |

| 7;4 | M | 116 | 116 | 104 | 110 |

| 7;9 | F | 100 | 106 | 96 | 101 |

| 8;1 | F | 90 | 116 | 110 | 113 |

| 8;3 | M | 81 | 86 | 100 | 92 |

| 8;9 | F | 103 | 100 | 92 | 95 |

| 9;4 | M | 102 | 102 | 98 | 100 |

| 9;6 | M | 91 | 98 | 96 | 96 |

CELF-3: Semel et al. (1995).

TONI-3: Brown et al. (1997).

Receptive Language Score.

Expressive Language Score.

Total Language Score.

Group comparisons

The groups were similarly diverse socio-educationally based on the similar ranges of parents’ educational and occupational experiences (Hollingshead, 1975). The mothers and fathers for each group had median educational levels of some college, with a range from 10th grade to graduate degrees. Similarly, both groups had a wide range of parent occupation levels. The groups also did not differ in performance IQ (t (23) = 1.777, p > 0.05).

The SLI group performed more poorly than the TLD group on all language testing. Comparison of the composite standard scores revealed significant group differences for receptive language (MSLI = 88.3, SD = 9.3), (MTLD = 105.3, SD = 8.5); t (23) = 4.7677, p < 0.001, expressive language (MSLI = 76.0, SD = 9.2), (MTLD = 103.1, SD = 7.1); t (23) = 7.5439, p < 0.001 and total language (MSLI=80.9, SD=7.8) (MTLD = 103.9, SD = 8.0); t (23) = 7.2838, p < 0.001 composite CELF-3 scores (Semel et al., 1995).

Stimuli

The auditory stimuli were produced by a female speaker and digitally altered to create four conditions for the experimental tasks. Color pictures were used to represent continuum endpoints for the identification task.

Auditory stimuli

Four consonant–vowel–consonant (CVC) minimal pairs were used to create four sets of 12-step continua. The four continua represented different conditions: (a) word–word (WW: feet–feed); (b) nonword–nonword (NN: zeet–zeed); (c) word–nonword (WN: cheat–chead); and (d) nonword–word (NW: reat–read). The initial consonants (C1) of each minimal pair differed by at least two distinctive features. The final consonants (C2) were alveolar stops that differed in voicing (i.e. /d/ or /t/). These minimal pairs became the endpoints of the continua. All continua had the same steady state vowel.

The four real words selected appear frequently in adult and third grade level written texts (Carroll, Davies, & Richman, 1971), and in the oral vocabulary of first grade children (Moe, Hopkins, & Rush, 1982). Read is most frequent, followed by feet, feed and cheat (Carroll et al., 1971; Moe et al., 1982).

The continua were created by editing selected portions of naturally produced CVCs, the eight endpoint words and nonwords (i.e. feet, feed, cheat, read; chead, reat zeet and zeed), after first determining the typical temporal characteristics of the segments. The second author, who is a native English speaker from the New York area, digitally recorded five productions of each endpoint CVC. The CVCs were digitized and edited. The editing and creation of the continua were guided by previous studies of vowel duration as a cue to final consonant voicing (Raphael, 1972).

There were 13 tokens in each of the four 12-step continua. A token consisted of C1 + V + 85ms stopgap + C2. The same four edited C1s were used for all continua. The C1 for each continuum was created by using altered natural productions. C1 segments (i.e. /ʧ/, /f/, /r/, /z/) were extracted from four representative utterances. These segments were modified so that each C1 was 120 ms. Segment durations were determined by the means of the sample utterances.

The cue to the voicing characteristic was vowel duration which varied in 20 ms steps from 110 to 350 ms along each continuum consistent with previous studies of vowel duration and final consonant voicing (Raphael, 1972). The vowels were created from one natural 270 ms /i/ wav file. The same V + 85 ms stopgap tokens were used for all continua. The tokens were created without the two secondary cues to final consonant voicing: the aspiration and the descending transition that naturally follow the steady state preceding voiced final alveolar stops.

C2 was an ambiguous final consonant created by extracting the first 15 ms from one natural final consonant /t/ produced in a representative CVC. These 13 sound files (V + Stopgap + C2) were each copied three more times, yielding four identical sets each containing 13 VC tokens. To these, each of the four C1s was added. This yielded four 12-step continua. Stimulus intensity variations were controlled and noise was eliminated. Peak amplitudes of −2.68 dB were maintained for all vowels without frequency clipping. The mean amplitude of the 110 ms vowels was 58 dB and the mean amplitude of the 350 ms vowels was 68 dB SPL. These differences are natural correlates to durational differences.

Visual stimuli

Computer-generated color picture referents (Boardmaker, 1998) for each of the four words and abstract figures for the four nonwords were printed on index cards. A red or blue sticker on each picture corresponded to identical stickers placed on two computer keyboard keys (i.e. the 1 and the 0 keys). During the presentation of each continuum, the pair of pictures was presented on the computer screen above their corresponding keys.

Procedures

Each continuum was presented separately. There were three training phases and a computerized identification task that was designed and presented using E-Prime (Psychology Software Tools, Inc., 1999). Data were recorded from categorical key presses for each stimulus presented. It took approximately 1.5 h to administer the training and the four identification conditions for the experimental task.

Training

First, the examiner introduced the referent pictures for each of the stimulus words ( feet, feed, cheat and read) and nonwords (zeet, zeed, chead and reat). Then, the child was asked to point to and name each picture. The child was also asked to describe or define each word, and use each in a sentence. The next training phase required the child to identify each word by selecting its corresponding picture. In the first of these, the children were asked to point to the corresponding picture for each pair (i.e. cheat/chead, reat/read, feet/feed and zeet/zeed). The second response required pressing one of two keys that were color coded to match a corresponding dot on each picture. All children reached the criterion of 3/3 consecutive correct pointing and button press responses. In the third training phase, the paired endpoints for each condition (i.e. WW, NW, WN and NW) were presented through headphones. Each pair was presented in a block of 12 randomly ordered trials with an interstimulus interval (ISI) of 5 s. The training block for each condition was repeated a maximum of seven times to meet the criterion of 10/12 trials correct (binomial distribution p = 0.016). The correct pair of pictures for each block was affixed to the computer screen of a PC laptop. Each picture had a red or blue sticker that corresponded to red and blue stickers on the two keyboard response keys. The child was told which endpoint pair would be presented and then responded by key press. The child received verbal feedback after each trial and at the end of each block.

Experiment

After a child reached criterion for a given pair, the experimental identification task for that pair was initiated. The presentation order of the experimental continua was varied randomly across children. Each experimental continuum was presented in three blocks of 26 randomized trials, including two repetitions of each stimulus. The ISIs were 5 s and children had a maximum of 5 s to make a response. Each block was approximately 3.5 min long. There were 78 trials per continuum (26 trials × 3 blocks = 78 trials). Two versions of the experiment were used to vary the location of responses on the keyboard. Half of the children in each group received Version 1 and half received Version 2. Children were given breaks, snacks and small prizes between blocks to maintain motivation.

Results

All 26 children participated in the computerized training. Data from one child with SLI was excluded because of visual-motor difficulty while pressing the response keys. After five repetitions of one block in Training 2, she expressed frustration and refused to continue. All the other children completed the training and all four conditions of the experimental phase.

Training task analysis

Children with SLI were similar to their TLD peers in learning the acoustic properties of the endpoint stimuli and associating them with the appropriate key press. Children with SLI did not require more training than the TLD children for three of the four continua. There were no between-group differences for mean number of blocks needed to reach criteria, t (23) p’s > 0.05:WW (MTLD = 4.46, SDTLD = 0.88) vs. (MSLI = 4.92, SDSLI=1.38); NW (MTLD = 4.69, SDTLD=1.11) vs. (MSLI = 5.00, SDSLI = 0.95); WN (MTLD = 4.62, SDTLD=0.96) vs. (MSLI=4.83, SDSLI = 1.27). For one condition, NN, SLI children required slightly more training than the TLD group (MTLD=4.08, SDTLD = 0.28), (MSLI=4.58, SDSLI = 0.79); t (23) = 0.9930, p = 0.04, d = 0.94. This between-group difference was less than one block.

Experimental task analysis

Because this study examines a near-continuous variable (i.e. vowel duration), probit analysis, which is a linear duration-response curve of the form a + b* duration, was used to determine the response distributions of the SLI and TLD groups for all four continua. Predicted mean percentages of CV/t/responses were calculated at 80% (0.80 probability level), corresponding to the area of certainty for the short vowel end of the continuum (e.g. feet); 65% (0.65 probability level), within the area of uncertainty (e.g. feet-like), 50% (0.50 probability level), for the category boundary (e.g. stimuli between feet and feed), 35% (0.35 probability level), within the other area of uncertainty (e.g. feed-like) and 20% (0.20 probability level), corresponding to the area of certainty for the long vowel end of the continuum (e.g. feed).

Group and condition comparisons were made by applying t-tests to the defined probit points. These points were the vowel durations at which the response rates were 80%, 65%, 50%, 35% and 20%. All findings reported as significant have been adjusted for multiple tests (i.e. the corrected 0.01 alpha level, p = 0.0005, and the corrected 0.05 alpha level, p = 0.0023).

Vowel duration as a cue

The overall directions of the four identification functions indicate that both groups approached 100% CV/t/ responses at short vowels and approached 0% CV/t/ responses at long vowels (see Figure 1). In general, the children used vowel duration as a cue to the voicing characteristic of the final consonants. Short vowels showed better responses overall than long vowels. This is most likely an artifact of stimulus creation because the downward transition for long vowels was deleted in order to remove any additional cues specific to voiced final consonants. Nevertheless, there were group differences in the areas of certainty, uncertainty and category boundary.

Figure 1.

Probability of response rates at vowel durations by continua and group. This figure shows the mean SLI (●) and TLD (Δ) identification functions as fitted response curves based on the probit analysis for WW (feet–feed), NN (zeet–zeed), WN (cheat–chead) and NW (reat–read). Dotted lines represent the duration of responses at 80%, 50% and 20% identification, respectively, for each group. Error bars are extended to two standard errors on either side of durations where appropriate.

Of the four continua tested, the SLI group performed most similarly to the TLD group on the WW (i.e. feet–feed) continuum differing only in responses at the area of certainty at the short vowel end of the continuum (see below). All other aspects of the WW function did not show group differences. For the NN and NW continua, group differences were observed from the short vowel end of the continuum through the category boundary. The WN continuum yielded no between group differences at the short vowel end of the continuum. However, differences were observed at the category boundary throughout the long vowel end of the continuum (see Figure 1).

Areas of certainty

In categorical perception tasks with two-alternative-forced-choice designs, preferential selection of one response choice at the ends of continua is expected. This preference indicates response certainty. In the current study, probit analysis predicted the vowel durations at which response certainty (CV/t/ response rates were equal to or greater than 80% and equal to or less than 20%) was reached for each group and for each continuum. Figure 1 shows that mean certainty was reached for the WW continuum, by the TLD group at 169.5 ms (SE = 5.3) at the feet end of the continuum, and at 310.8 ms (SE = 5.8) at the feed end of the continuum, whereas certainty was reached by the SLI group at 139.8 ms (SE = 7.6), and at 315.5 ms (SE = 7.5), respectively. There was a large effect size difference for the short vowel (t (21) = 3.1933, p = 0.0014, d = 1.31), and no difference for the long vowel (p > 0.05). Similar group differences were observed for the zeet–zeed and reat–read continua. The TLD group showed certainty (i.e. 80% or greater response rates) closer to the category boundary for zeet (Mzeat = 155.0; SE = 8.0), and reat (Mreat = 121.9 ms; SE = 8.8) for the longer vowel durations than the SLI group (Mzeet =102.9 ms, SE = 12.7; Mreat = 41.7 ms, SE = 18.7), respectively, t (21) = 3.4618, p = 0.0005, d=1.2; and t (21) = 3.8717, p = 0.0001, d = 1.57). There were no differences between children with TLD (Mzeed = 362.4 ms, SE = 10.6; Mread = 315.9 ms, SE = 7.9) and with SLI (Mzeed = 350.1 ms, SE = 12.3; Mread = 312.6, SE = 11.2) in certainty responses for the longer vowels (p’s > 0.05).

For WN, the 80% probit point at the short vowels end of the continuum (i.e. the cheat end) did not differ between groups (MTLD = 173.6, SE = 4.6); (MSLI = 164.2, SE = 7.1); p > 0.05, whereas the response certainty at the long vowels end of the continuum (i.e. the chead end) differed. The children with SLI reached mean certainty at a vowel duration of 347.0 ms (SE = 9.1) and the children with TLD reached mean certainty at 295.1 ms (SE = 4.8) (t (21) = 5.0700, p < 0.0001, d = 2.06).

In summary, for three of the continua (WW, NN and NW), the SLI group reached certainty at shorter vowel durations, indicating a different certainty point (i.e. category boundary) for CV/t/, than the TLD group. For one continuum (WN), there was no group difference for point of certainty at the short vowel end (i.e. cheat). However, for the long vowel end of the continuum (i.e. chead) children with SLI reached certainty at a longer vowel duration than the TLD group.

Phoneme perception boundaries

In categorical perception tasks, tokens in the midpoints of continua are ambiguous and equivocal responses are expected. A response rate with a 50% probability determines the phoneme perceptual boundary. Probit analysis was used to determine the phoneme boundary (the group mean for the vowel duration at which the probability of a CV/t/ response was 50%) for each continuum. We found group differences for three of the four continua: NN, NWand WN. Category boundaries for NN and NW continua were at shorter vowel durations for the SLI group than for the children with TLD. For zeet–zeed, the mean SLI category boundary was 226.5 ms (SE = 6.3) and the mean TLD boundary was 258.7 ms (SE = 5.5), t (21) = 3.8641, p = 0.0001, d=1.55. For reat–read, the mean SLI category boundary was 177.2 ms (SE = 8.2), and for children with TLD it was 218.9 ms (SE = 4.9), t (21) = 4.3602, p < 0.0001, d = 1.81. The mean category boundary for cheat–chead was longer for the children with SLI than for the children with TLD (MSLI = 255.6 ms, SE = 5.0), (MTLD = 234.4 ms, SE = 3.4); t (21) = 3.5071, p = 0.0005, d = 1.44. There was no group difference for feet–feed (MSLI = 227.7, SE = 4.7); (MTLD = 240.2, SE = 3.8); t (21) = 2.0748, p > 0.0023.

Areas of uncertainty

Identification performance was also examined in the areas where tokens were ambiguous (i.e. response uncertainty). Probit analysis was used to sample two points in each continuum: the 0.65 probability and the 0.35 probability of a CV/t/ response (i.e. 65% and 35% CV/t/ responses). Here again there were group differences for the NN and NW continua at the short vowel end. The children with SLI reached the 0.65 probability response rate (PRR) at a mean vowel duration of 169.9 ms (SE = 8.2) for zeet whereas the TLD group reached it at a mean vowel duration of 211.2 ms (SE = 5.6), t (21) = 4.1799, p < 0.0005, d = 1.70. Similarly, the children with SLI reached the 0.65 PRR at a mean of 115.2 ms (SE = 12.4) for reat, and the children with TLD reached that PRR at a mean of 174.5 ms (SE = 6.1), t (21) = 4.2789, p < 0.0005, d = 1.83. For feet, the groups performed similarly; the children with SLI reached the 0.65 PRR at a shorter vowel duration (MSLI = 187.5 ms, SE = 5.5) than the children with TLD (MTLD = 207.8 ms, SE = 4.1), approaching the corrected value for significance, t (21) = 2.9876, p = 0.0028, d = 1.2. At the long vowel end, although responses for read and zead approached uncorrected significance (p’s < 0.05), only the chead responses yielded a significant group difference at the 0.35 PPR (MSLI = 297.5 ms, SE = 6.4); (MTLD = 262.2 ms, SE = 3.7), t (21) = 4.7549, p < 0.0001, d = 1.99.

Lexical effect

In WN continua, a preference for selecting the real word (i.e. as indicated by a category boundary shift away from the real word) indicates a lexical effect (Ganong, 1980). In the current study, both groups demonstrated a lexical effect for the WN and the NW continua. For children with SLI, the mean difference between the NW (MSLI = 177.2 ms, SE = 8.2) and the WN (MSLI = 255.6 ms, SE = 5.0) category boundaries (i.e. at the 0.50 PRR) was 34.4 ms (SE = 9.2), t (21) = 2.3936, p < 0.05, d = 3.43. For the TLD group, the mean difference between the NN (MTLD = 218.9 ms, SE = 4.9) and the WN (MTLD = 234.4 ms, SE = 3.4) category boundaries was 20.7 ms (SE = 9.2), t (21) = 2.2496, p<0.05, d = 3.74. The difference in effect sizes indicates a much stronger lexical effect for children with SLI than for their typically developing peers. Further evidence of a stronger lexical effect for children with SLI came from their more frequent identification of continua tokens on the nonword side of their category boundaries as real words (see Figure 1 and previous section) in the WN and the NW continua (p’s < 0.0005). The WW vs. NN continua did not yield a boundary shift for either group (p’s > 0.05) as we had expected.

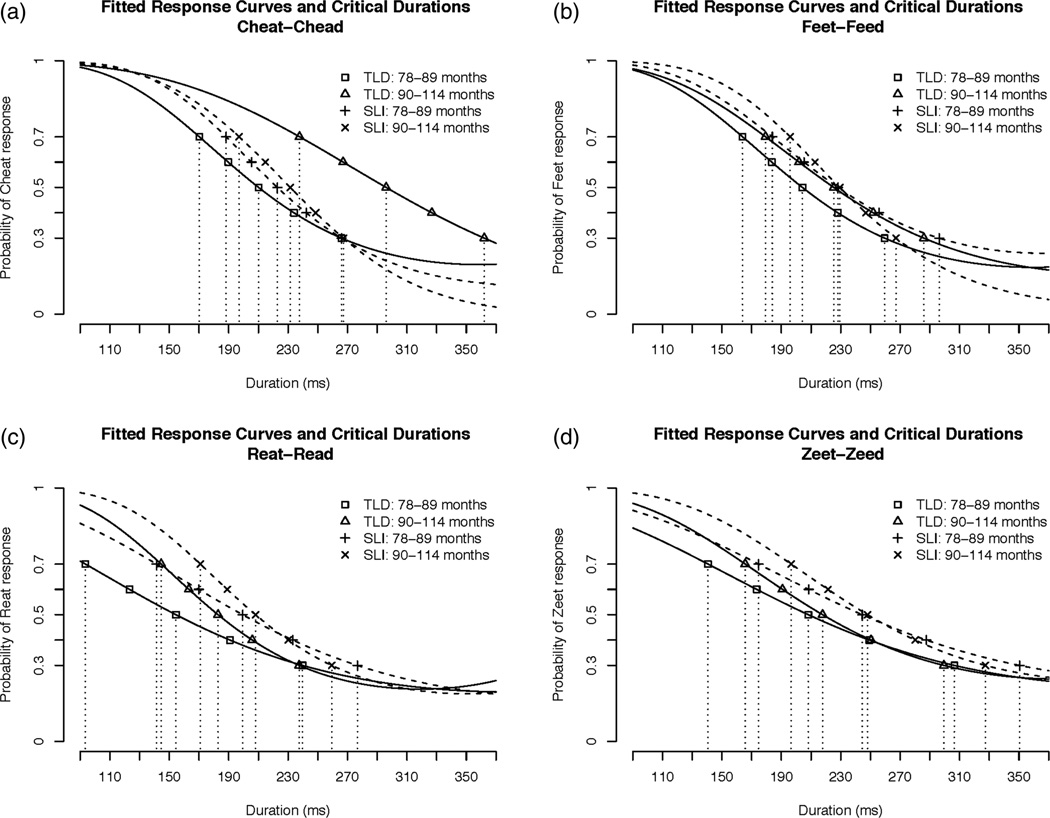

Age effects

There was an overall age effect; older children (above the median split of 7;5–89 months) were always more likely to give a /t/ response at shorter vowel durations, with the crossover varying with the pair. There was a group by age interaction, but as is apparent in Figure 2, it resulted only from the cheat–chead continuum for the older children with TLD. The older children with TLD exhibited a higher proportion of cheat responses throughout the continuum with only a gradual linear decrease as vowel duration increased. The remaining stimuli did not reveal age differences.

Figure 2.

Fitted response curves and critical durations of (a) cheat–chead, (b) feet–feed, (c) reat–read and (d) zeet–zeed by age and group.

Summary

Children with SLI were able to recognize and identify endpoint stimuli similarly to their TLD peers, but reached certainty at different points along the continua. Children with SLI needed more durational difference than their TLD peers to make the certain identification. Additionally, children with SLI showed category boundaries at shorter vowel durations for three of the continua, and at longer vowel duration for one (cheat–chead). Both groups demonstrated lexical effects in the WN and NW continua. Children with SLI had stronger lexical effects than the TLD group. The children with SLI were most similar to the TLD group for the WW (i.e. feet–feed) continuum.

Discussion

The current investigation extends previous speech perception research in children with SLI by examining the relation between the perception of a temporal speech cue (i.e. vowel duration as a cue to final consonant voicing) and lexical knowledge (i.e. word status) in an identification task. Children with SLI did not differ from their TLD peers in the amount of training they needed to learn the experiment task. They did not have the difficulty reported elsewhere for other perception tasks (Robin, Tomblin, Kearney, & Hug, 1989). The identification task employed digitally edited natural speech and had minimal working memory demands (Coady et al., 2005, 2007). Therefore, group differences cannot be attributed to overall task performance asymmetries.

For the four continua, all of the children used short vowels as a cue for CV/t/ and long vowels as a cue for CV/d/ as in adults (Raphael, 1972). However, the children with SLI were less consistent than their TLD peers. Their performance was most similar to the TLD group for theWW( feet–feed) continuum. Otherwise, they exhibited less certainty overall (larger areas of uncertainty), and stronger lexical effects than the TLD group for the WN (cheat–chead) and NW (reat–read) continua.

Because their responses to the WW ( feet–feet) continuum were similar to the control group, we can surmise that children with SLI used phonological representations in long-term memory to support the use of vowel duration for phoneme and lexical identification. However, it would be erroneous to assume that children with SLI acquire typical and stable phonological representations for familiar words as has been suggested (Coady et al., 2005). If this were the case, then their responses to feet, read and cheat should have been similar to the TLD group; only the NN (zeet– zeed) continuum would have shown differences. Only one of the real words ( feed) actually showed similar responses. A greater range of uncertainty was evident in the WN and NW continua as well as the NN continuum. Further, the stronger lexical effect shown as preferences for real words on the nonword side of the phoneme boundaries indicate that children with SLI have unstable phonological representations for words as well as for nonwords as evidenced by the over-selection of read and cheat. Only under controlled conditions, where the context limited lexical selection (i.e. in this case a two-alternative forced choice task in which both ends of the continuum were familiar words, feet–feet), do they recognize words in the same way as their peers. Thus, in all other cases, children with SLI used the vowel duration cue differently than their typically developing peers.

Further research is needed to investigate how these children use other acoustic cues to phonemic distinctions in English and in other languages. Children with SLI may differ from their TLD peers in their acoustic weighting strategies (Nittrouer & Lowenstein, 2007). The current study demonstrated their preference for lexical rather than vowel duration information. However, vowel duration may not be as salient a cue as some other acoustic cues (see Nittrouer & Lowenstein, 2007 for a review). Children with SLI may be more attuned to other cues. Further research is needed to identify those acoustic cues or contexts that are more salient to children with SLI, and that may supersede lexical preferences. Such data would determine which cues and under what conditions novel words are recognized as novel, thus normalizing the lexical effect.

Because children with SLI have more limited vocabularies or less detailed lexical representations than their peers, their use of acoustic weighting strategies may be under-developed. They may require more interrelated contextual cues than children who are TLD. The contextual cues that most benefit children’s lexical development as they learn to segment the speech stream into words, syllables and segments remain unknown. Identification paradigms similar to the one used in the current study have been used with adults to explore a variety of word and sentence contexts (Borsky, Tuller, & Shapiro, 1998; Connine & Clifton, 1987) and could be used to explore acoustic, phonological, lexical and sentence processing in children with SLI.

These results may also be related to other findings regarding SLI. Children with SLI were more likely than their dyslexic and typically developing peers to accept altered words regardless of whether or not they were in contexts (e.g. brown(m) bell vs. brown(m) lamp) that led to potential assimilation (Marshall, Ramus, & van der Lely, 2010). The common finding that children with SLI perform more poorly on nonword repetition may also reflect indirectly a tendency to identify tokens as instances of related real words leading to incorrect repetitions.

Our findings indicated that when presented with a new CVC word (nonword in this experiment), children with SLI were more likely to assume that it is a word with which they are familiar, rather than recognizing it as a new word they need to learn. For example, if chead were a new real English word in a sentence, but was identified by a child as the familiar word, cheat, the child would attach incorrect meanings and usages to cheat. Lexical acquisition would therefore be negatively affected (Edwards & Lahey, 1996). This may, in part, contribute to the poor semantic knowledge demonstrated in children with SLI (McGregor, Newman, Reilly, & Capone, 2002). In auditory lexical processing and access, word forms are processed through the phonological system first even if the task is semantic. Further research is needed to explore the direct effect of phonological errors in lexical identifications on semantic-based lexical access and lexical development in children with SLI.

Importantly, the results of this investigation contribute to our understanding of the underlying cause of the perceptual deficits demonstrated in children with SLI. Although many researchers agree that children with SLI have impaired speech perception (Bishop et al., 1999; Gathercole & Baddeley, 1990; Leonard, 1989; Leonard et al., 1992; Mody, Studdert-Kennedy, & Brady, 1997; Sussman, 1993; Tallal et al., 1993), there is disagreement as to the nature and underlying cause of the deficits. The auditory temporal processing view attributes phonological misrepresentations to abnormalities of the lower level auditory system (see Tallal et al., 1993). In this view, children with SLI have auditory systems that are unable to process temporal characteristics of brief, rapidly sequenced, or subtly different acoustic signals. The cognitive–linguistic view assumes that children with SLI have normal auditory systems, but have deficits in their abilities to recognize speech sounds accurately leading to phonological, lexical and morphosyntactic deficiencies. In short, the disagreement is whether phonological misrepresentations can be attributed to processing deficits in the auditory system or in the cognitive–linguistic system (Mody et al., 1997; Studdert-Kennedy et al., 1994; Sussman, 1993). Our findings do not support the presence of an auditory level deficit for vowel duration. Specifically, contrary to previous studies, the children with SLI were able to discriminate fine temporal distinctions (Elliot & Hammer, 1988; Tallal & Stark, 1981). This occurred for the feet–feet continuum. For this continuum, children with SLI had slowly sloping identification functions similar to their TLD peers; both groups had similar sensitivity to the 20 ms differences in vowel duration. If the perceptual deficit is on the auditory level, children with SLI should not have been able to perceive any of the continua similarly to the children who were TLD.

We also found that duration of the temporal cue (Tallal et al., 1993) was irrelevant. The vowel duration cues examined in this study (i.e. 110–350 ms) were longer than transition durations or vowel durations used in most previous studies (Frumkin & Rapin, 1980; Tallal & Piercy, 1975), and yet, children with SLI had less accurate identification at both ends of the continua. Long and short vowels were poorly categorized depending on the particular continuum. Rather than a fundamental perceptual deficit for duration, vowel duration had limited value as a cue for final consonant voicing in children with SLI. The poor use of this cue in the presence of adequate fine discrimination is consistent with previous findings for some spectral cues. For example, children with SLI have adequate discrimination and poor identification of syllables /ba/ vs. /da/ (Bishop, Hardiman, Uwer, & von Suchodoletz, 1997; Sussman, 1993). Poor use of cues for categorizing segments may result in atypical phonological representations (Bishop et al., 1997; Gathercole & Baddeley, 1990; Sussman, 1993).

In summary, the current study lends support to the view that the perceptual deficits associated with SLI reflect cognitive-linguistic factors (Sussman, 1993) rather than auditory processing (Tallal et al., 1993). Further, it suggests that phonetic cues are over-ridden by linguistic information causing some phonological representations to be atypical.

Acknowledgment

Lawrence J. Raphael, PhD provided valuable input and assistance in the design of the stimuli and the experiment.

This work was supported by grants RO1DC003885, 1RO1DC011041, and P50 DC00223 (Project 4) from the NIDCD and by a PSC-CUNY Research Grant to the first author. The research was conducted at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and was included in a dissertation by the second author, under the direction of the first author, at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Guidelines for screening for hearing impairment and middle-ear disorders. Asha. 1990 Apr;32(Suppl. 2):17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DVM, Bishop S, Bright P, James C, Delaney T, Tallal P. Different origins of auditory and phonological processing problems in children with language impairment: Evidence from a twin study. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1999;42:155–168. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4201.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DVM, Hardiman M, Uwer R, von Suchodoletz W. Atypical long-latency auditory event-related potentials in a subset of children with specific language impairment. Cognition. 1997;10:576–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00620.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boardmaker . Boardmaker for Windows [Software] Pittsburgh, PA: Mayer-Johnson, Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Borsky S, Tuller B, Shapiro L. “How to milk a coat”: The effects of semantic and acoustic information on phoneme categorization. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1998;103:2670–2676. doi: 10.1121/1.422787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradlow AR, Kraus N, Nicol TJ, McGhee TJ, Cunningham J, Zecker SD, Carrell TD. Effects of lengthened formant transition duration on discrimination and neural representation of synthetic CV syllables by normal and learning-disabled children. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1999;106:2086–2096. doi: 10.1121/1.427953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L, Sherbenou R, Johnsen S. Test of Nonverbal Intelligence-3 (TONI-3) Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Burlingame E, Sussman HM, Gillam RB, Hay JF. An investigation of speech perception in specific language impairment on a continuum of formant transition duration. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2005;48:805–816. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/056). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton MW, Baum SR, Blumstein SE. Lexical effects on phonetic categorization of speech: The role of acoustic structure. Journal of Experimental Psychology in Human Perceptual Performance. 1989;15:567–575. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.15.3.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JB, Davies P, Richman B. Word frequency book. New York: Houghton Mifflin; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Coady JA, Evans JL, Mainela-Arnold E, Kluender KR. Children with specific language impairments perceive speech most categorically when tokens are natural and meaningful. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2007;50:41–57. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coady JA, Kluender KR, Evans JL. Categorical perception of speech by children with specific language impairments. Journal of Speech, Language, Hearing Research. 2005;48:944–959. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/065). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connine CM, Clifton C. Interactive use of lexical information in speech perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1987;13:291–299. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.13.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta H, Shafer VL, Morr M, Kurtzberg D, Schwartz RG. Electrophysiological indices of discrimination of long duration, phonetically similar vowels in children with typical and atypical language development. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2010;53:757–777. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0123). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J, Lahey M. Auditory lexical decisions of children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1996;39:1263–1273. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3906.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot LL, Hammer M. Longitudinal changes in auditory discrimination in normal children and children with language learning problems. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1988;53:467–474. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5304.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J, Viele K, Kass R, Tang F. Grammatical morphology and perception of synthetic and natural speech in children with specific language impairments. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2002;45:494–504. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/039). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox R. Effect of lexical status on phonetic categorization. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1984;10:526–540. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.10.4.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frumkin B, Rapin I. Perception of vowels and consonant-vowels of varying duration in language impaired children. Neuropsychologia. 1980;18:443–453. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(80)90147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganong W. Phonetic categorization in auditory word perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1980;6:110–125. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.6.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole S, Baddeley A. Phonological memory deficits in language disordered children: Is there a causal connection? Journal of Memory and Language. 1990;29:336–360. [Google Scholar]

- Greenlee M. Learning the phonetic cues to the voiced-voiceless distinction: A comparison of child and adult speech perception. Journal of Child Language. 1980;7:459–468. doi: 10.1017/s0305000900002786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayiou-Thomas ME, Bishop DVM, Plunkett K. Simulating SLI: General cognitive processing stressors can produce a specific linguistic profile. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004;47:1347–1362. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/101). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill P, Hogben J, Bishop D. Auditory frequency discrimination in children with specific language impairment: A longitudinal study. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2005;48:1136–1146. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/080). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AA. Four-factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1975. (Unpublished manuscript) [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowicz C. Computational complexity and the acquisition of functional categories by French-speaking children with SLI. Linguistics. 2003;41:175–211. [Google Scholar]

- Krause SE. Vowel duration as a perceptual cue to postvocalic consonant voicing in young children and adults. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1982;71:990–995. doi: 10.1121/1.387580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard LB. Language learnability and specific language impairment in children. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1989;10:179–202. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard LB. Children with specific language impairment. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard L, McGregor K, Allen GD. Grammatical morphology and speech perception in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research. 1992;35:1076–1085. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3505.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinis T. On the nature and cause of specific language impairment: A view from sentence processing and infant research. Lingua. 2011;12:463–475. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall CR, Ramus F, van der Lely H. Do children with dyslexia and/or specific language impairment compensate for place assimilation? Insight into phonological grammar and representations. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 2010;27:563–586. doi: 10.1080/02643294.2011.588693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marton K, Schwartz RG. Working memory capacity and language processes in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2003;46:1138–1153. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/089). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur G, Bishop D. Frequency discrimination deficits in people with specific language impairments reliability, validity, and linguistic correlates. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004;47:527–541. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/041). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor KK, Newman RM, Reilly RM, Capone NC. Semantic representation and naming in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2002;45:998–1014. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/081). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody M, Studdert-Kennedy M, Brady S. Speech perception deficits in poor readers: Auditory processing or phonological coding? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1997;64:199–231. doi: 10.1006/jecp.1996.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moe AJ, Hopkins CJ, Rush RT. The vocabulary of first-grade children. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Nittrouer S, Lowenstein JH. Children’s weighting strategies for word-final stop voicing are not explained by auditory sensitivities. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2007;50:88–73. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychology Software Tools, Inc. E-prime (Version 1.0) [Computer software] Pittsburgh, PA: Psychology Software Tools, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael LJ. Preceding vowel duration as a cue to the perception of voicing of American English consonants in word-final position. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1972;51:1296–1303. doi: 10.1121/1.1912974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin DA, Tomblin JB, Kearney A, Hug LN. Auditory temporal pattern learning in children with speech and language impairments. Brain and Language. 1989;36:604–613. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(89)90089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen S. Auditory processing in dyslexia and specific language impairment: Is there a deficit? What is its nature? Does it explain anything? Journal of Phonetics. 2003;31:509–527. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen S, Adlard A, van der Lely H. Backward and simultaneous masking in children with grammatical specific language impairment: No simple link between auditory and language abilities. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2009;52:396–411. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0114). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semel E, Wiig E, Secord W. Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-3 (CELF-3) San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Shafer VL, Morr ML, Datta H, Kurtzberg D, Schwartz RG. Neurophysiological indices of speech processing deficits in children with specific language impairment. Cognitive Neuroscience. 2005;17:1168–1180. doi: 10.1162/0898929054475217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer VL, Ponton C, Datta H, Morr M, Schwartz RG. Neurophysiological indices of attention to speech in children with specific language impairment. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2007;118:1230–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark RE, Heinz JM. Vowel perception in children with and without language impairment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1996;39:860–869. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3904.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studdert-Kennedy M, Liberman AM, Brady SA, Fowler AE, Mody M, Shankweiler DP. Lengthened formant transitions are irrelevant to the improvement of speech and language impairments. The Haskins Laboratories Status Report on Speech Research. 1994;119:35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman JE. Perception of formant transition cues to place of articulation in children with language impairments. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1993;36:1286–1299. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3606.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallal P. Rapid auditory processing in normal and disordered language development. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1976;19:561–571. doi: 10.1044/jshr.1903.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallal P, Miller S, Fitch R. Neurobiological basis of speech: A case for the preeminence of temporal processing. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1993;682:27–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb22957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallal P, Piercy M. Developmental aphasia: The perception of brief vowels and extended stop consonants. Neuropsychologia. 1975;13:69–74. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(75)90049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallal P, Stark R. Speech acoustic cue discrimination abilities of normally developing and language impaired children. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1981;69:568–574. doi: 10.1121/1.385431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallal P, Stark RE, Kallman C, Mellits D. Perceptual constancy for phonemic categories: A developmental study with normal and language impaired children. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1980;1:49–64. [Google Scholar]