Abstract

With the aging of the population and continuing advances in health care, patients seen in the primary care setting are increasingly complex. At the same time, the number of screening and chronic condition management tasks primary care providers are expected to cover during brief primary care office visits has continued to grow. These converging trends mean that there is often not enough time during each visit to address all of the patient’s concerns and needs, a significant barrier to effectively providing patient-centered care. For complex patients, prioritization of which issues to address during a given visit must precede discrete decisions about disease-specific treatment preferences and goals. Negotiating this process of setting priorities represents a major challenge for patient-centered primary care, as patient and provider priorities may not always be aligned. In this review, we present a synthesis of recent research on how patients and providers negotiate the visit process and describe a conceptual model to guide innovative approaches to more effective primary care visits for complex patients based on defining visit priorities. The goal of this model is to inform interventions that maximize the value of available time during the primary care encounter by facilitating communication between a prepared patient who has had time before the visit to identify his/her priorities and an informed provider who is aware of the patient’s care priorities at the beginning of the visit. We conclude with a discussion of key questions that should guide future research and intervention development in this area.

Keywords: Patient-centered, Primary care, Health IT, Diabetes, Complex patients

Patient Vignette. A 73 year old man with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and benign prostatic hypertrophy comes to see his primary care physician for a regularly scheduled visit. His lower back has been causing him pain that is interfering with his ability to get out of the house and he is sleeping poorly. He has been a widower for several years and has recently started a new relationship. Reviewing her previous progress note before entering the exam room, his physician recalls that he still smokes, his hemoglobin A1c has been mildly elevated, he is overdue for a pneumonia vaccination, and he has not yet filled his statin prescription. On entering the exam room, she also finds that her patient’s blood pressure is elevated.

In this visit vignette, the patient and provider encounter each other with a distinct set of priorities that are not necessarily aligned. Because the number of areas deserving attention exceeds the available time during the visit, the decision of which concerns to address first will determine the content of the visit and the subsequent trajectory of care.

1. Background

1.1. Patients are more complex

The aging of the primary care population coupled with better disease prevention and treatment efficacy means that more patients are living longer with multiple comorbidities that require complicated medical regimens.1 By 2020 there will be an estimated 130 million Americans with one or more chronic conditions.2 Patients with multiple chronic conditions have more outpatient visits per year, are prescribed multiple medications, generate more health care costs, have more adverse events, and have lower health-related quality of life.3 Many of these complex patients do not receive the full potential benefit of available health care interventions, often due to competing health demands, cost or other access barriers, medication side effects, and sub-optimal adherence to prescribed medicines.4–6 Effective management of these complex patients represents a major challenge in our current primary care system.

1.2. Visits are more packed

A concurrent trend has been the growing complexity of guideline-based primary care. The standard visit is increasingly defined by a long “laundry list” of best practice recommendations and quality measures involving disease management, preventive screening, and behavioral counseling. Abbo et al., for example, found that the number of clinical items addressed during a primary care visit increased from 5.4 in 1997 to 7.1 in 2005 (p<0.001),7 resulting in a decrease in minutes spent per clinical item from 4.4 to 3.8 (p=0.04). Ostbye et al. estimated that the time required to deliver high-quality care increases three-fold if a chronic condition such as diabetes is poorly controlled.8 Primary care providers report that they consider one-fourth of their patients to be complex, and that these patients tend to have more comorbidities but also mental health and socio-economic barriers to care.9 This confluence of increasing patient complexity and increasing primary care tasks places significant stress on the traditional primary care visit and creates barriers to productive interactions. Without new approaches to support the primary care of complex patients, millions of Americans will continue to receive sub-optimal care despite the availability of effective therapies and interventions that reduce health risks and improve health. Optimizing care for this growing patient population is therefore a national priority.

2. Methods

In this review, we present a synthesis of recent research on how patients and providers negotiate the visit process and describe a conceptual model to guide innovative approaches to more effective primary care visits for complex patients based on defining visit priorities. Primary research articles were drawn from the English-language literature and evaluated by the authors for relevance to: patient complexity, differences in how patients and their providers prioritize care, and the consequences of these differences. We examined both randomized and non-randomized studies (n=78) and reviewed reference lists from identified studies for additional studies relevant to our review. These data were incorporated into a conceptual model (see figures) designed to inform innovative primary care approaches for complex patients.

2.1. The impact of patient complexity on visit content

Recent work investigating the content of primary care visit interactions provides evidence for the increasing need for effective prioritization among complex patients. Tai-Seale et al. recorded and analyzed primary care encounters and found that the first item addressed received the bulk of the attention (5 min vs. 1.1 min for the next 5–6 total topics addressed during the typical 15 min visit).10 This study demonstrates the fundamental importance of choosing which item to address first. Other studies have shown the consequences of multiple competing demands during a clinic visit: preventive screening declines with each additional concern brought up by patients,11 and more complex patients with diabetes are less likely to have glycemic medications intensified if above goal.12,13 These factors may contribute to the lower levels of satisfaction with health care reported by patients with multiple comorbidities.14 Parchman et al. directly observed primary office encounters involving 211 patients with type 2 diabetes and found that acute illness and other competing demands led patients and physicians to prioritize immediate needs and defer indicated services to subsequent visits.15 These data demonstrate that the choice of which issues to prioritize has a major influence on the subsequent content, quality, and decision making during the visit. To the extent that effective medical care for clinical problems improves clinical outcomes, finding ways to address multiple different problems in complex patients represents a critical goal for primary care.

2.2. Provider vs. patient priorities

Given that problems and concerns exceed the available allotted time for a given visit, it is clear that decisions must be made at each visit of what to discuss first. However, it is less clear how to explicitly define and negotiate the often-times differing priorities of providers and patients, and how to accomplish this negotiation in a timely manner during a too-brief visit encounter.

There is ample evidence on how patient and provider priorities differ. Physicians are trained to address disease prevention and risk reduction, generally with a focus on the highest clinical risk problems (e.g. heart disease or diabetes). Some evidence suggests that management priorities are also influenced to a certain extent by quality metrics. For example, one study found that PCPs may place a relatively higher priority on lower value interventions (e.g. microalbuminura screening) when these are used as performance measures.16 One innovative study using unannounced, standardized patients visiting 111 primary care physicians found that physicians were less likely to probe contextual “red flags” (e.g. suggestions from the standardized patients that they had concerns related to transportation needs, financial burdens, or caretaker responsibilities) than clinical red flags (e.g. descriptions of symptoms that could be attributed to medical problems).17 For more complex patients, providers report that they especially struggle with balancing multiple evidence-based guidelines when making treatment decisions.18 This challenge was underscored by a recent study demonstrating that the application of all relevant guidelines to a single complex patient would likely result in potential harm from adverse drug–drug interactions.19 Recognizing that guidelines alone are insufficient to guide care helps inform our framework by providing further evidence of the need to establish care priorities for a given visit.

In contrast to provider priorities, patients often have other concerns that outweigh the physician’s treatment goals.20 For example, older patients report valuing functional ability 21 and place a high priority on avoiding drug side effects.22 In an analysis based on responses from 353 older patients, researchers report that patients’ assessment of disease burden incorporates domains such as physical functioning, financial constraints, and self-efficacy, areas that are not always considered by their treating physicians.23 Other examples of prevalent concerns that are frequently unrecognized by providers include sleep or sexual function problems, financial problems, and stress related to care-giving.24–27 Knowing the patient’s top concerns helps the provider both to more effectively frame management decisions and also to activate appropriate members of the available care team.

Research using patient–provider pairs also has found only modest concordance in how patients and their providers prioritize medical issues. For example, one study of 127 patients with type 2 diabetes and their PCPs found low agreement on the top 3 specific diabetes treatment goals and strategies for that patient (all kappas were less than 0.40).28 In multivariable analyses, patients with more education, greater belief in the efficacy of their diabetes treatment, and who shared in treatment decision making with their providers were more likely to agree with their providers on treatment goals or strategies. This finding supports the hypothesis that enhancing patient–provider communication on both overall treatment goals and specific strategies to meet these goals may lead to improved patient outcomes. In a similar study involving 92 providers and 1169 patients with elevated blood pressure, patients were more likely than providers to prioritize symptomatic conditions such as pain, depression, and breathing problems. Concordance on health priorities was lower when patients had poor health status or other, non-health-related competing demands.29

2.3. Consequences of concordance

Improving communication during the visit is posited to improve clinical outcomes through multiple mechanisms, including higher quality of medical decisions, increased trust, and enhanced therapeutic alliances.30 Indeed, the lack of adequate communication and concordance about medication management has been associated with decreased medication adherence, particularly among complex patients facing financial stresses.31 In a study of 660 patients with chronic illnesses, for example, Piette et al. found that nearly one-third of patients who had difficulty affording their medicines did not discussed this problem with their physician.32 Among 912 patients with diabetes, the likelihood of patients forgoing their medications because of cost was significantly higher when patients’ trust in their physicians was low.33 This relationship between trust and medication adherence has also been seen with persistence with statin therapy.34 In our conceptual framework, efforts to improve communication about priorities can also improve communication about other barriers to care, leading to greater trust in the relationship and more effective medication-related management.

Effectively recognizing and working to align these sometimes discordant priorities represents a critical first step towards establishing an effective framework for care decisions. Indeed, studies have shown that PCPs can substantially improve their assessments when patients more effectively and pro-actively communicate their preferences.35,36 In Piette’s study cited earlier, for example, 72% patients who did discuss medication cost barriers with their providers found the conversation helpful.32 Current data suggest that patient–provider interactions could become significantly more effective if providers had a better understanding of the patient’s current priorities37–41 and were more aware of “unvoiced” agendas from the very beginning of the clinic visit.42,43 Indeed, in a study of 1065 patients with diabetes, Lafatta et al. found that patient-reported use of more collaborative goal setting was associated with greater perceived self-management competency and increased level of trust in the physician (p<0.05), which in turn were associated with improved glycemic control (p<0.05).44 Because high quality primary care is by definition longitudinal, patients and providers also have multiple opportunities over time to identify and address care priorities, and indeed these priorities may change over time as issues are addressed or circumstances change.

2.4. Conceptual model for prioritization

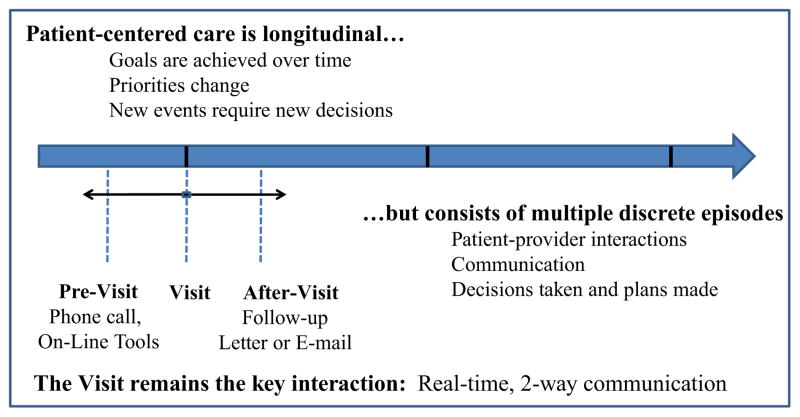

Truly patient-centered care requires that care interactions include consideration of patient priorities. In Figs. 1 and 2 we present a conceptual model for the primary care of complex patients. Fig. 1 graphically represents the conceptual interaction of longitudinal primary care with the episodic nature of this care. The figure illustrates the concept that key interactions occur in the “pre-visit”, “visit”, and “post-visit” contexts. Different modes of communication are possible in different contexts, although for non-visit interactions, these are often asynchronous (i.e. secure e-mail communications) and can be one-directional (i.e. mailed letters). One key point of this figure is that for complex patients and their primary care physicians, circumstances change over time, diseases progress and are managed in a step-wise fashion, and non-medical issues can intervene and must be addressed over time.

Fig. 1.

Patient-centered care for complex patients.

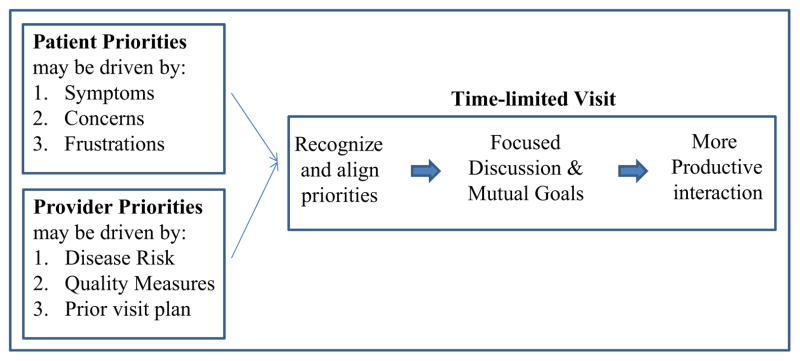

Fig. 2.

Conceptual model for how patient and provider prioritization can support more productive visit interactions.

Within this longitudinal temporal framework, it is important to recognize that actual care interactions are by definition episodic. While medical systems have increasingly evolved to enable non-visit based communications (such as e-mails, automated and nurse-initiated phone calls, and traditional letters), for most complex patients the in-person visit will continue to represent a critically important interaction point where two-way communication and negotiated decision-making can best be implemented. Face-to-face visits combine verbal and non-verbal cues, allow for focused discussions that lead to collaborative goal setting, and are often an ideal setting for translating plans into actions (e.g. writing medication orders, scheduling tests and making referrals). These in-person interactions also have intrinsic value in the longer-term goal of establishing trust and rapport between patient and provider. For this reason, innovative approaches to maximizing the value of these visits are needed.

By enabling patients to review and consider their health priorities prior to their next PCP visit and by informing providers of these priorities, the negotiation and decision-making process during primary care visit is facilitated, thereby reducing “discordant” decisions in which, for example, a medication is prescribed that the patient decides not to fill. Fig. 2 provides a graphic illustration for how we conceptualize the process of patient–provider prioritization. As reviewed above, patients and providers often (but not always) have different perceptions of relative health priorities. In an ideal setting for the primary care of complex patients, each visit could be used to identify the top priorities of both patient and physician, with priorities changing over time as circumstances change (e.g. symptoms resolve). Even in innovative systems that are experimenting with increased visit lengths for a small subset of the most complex patients, patients and providers can still only focus on a limited number of issues at each visit. By explicitly highlighting priorities, the stage is set both for negotiated goal setting and for maximizing the efficiency of the time-limited visit. This approach may be particularly effective in the context of clinical changes, such as a new diagnosis or addition of a new medication.

While theoretically a risk-based prioritization approach would focus management on the most clinically important issues, truly patient-centered care requires that patient priorities be recognized when considering multiple evidence-based options. If the patient has other, more pressing concerns, addressing these issues first may then lead to more successful management of the “higher risk” medical issues. Patient-level prioritization represents an alternative communication strategy that begins upstream from shared decision making, with the goal of facilitating individual decision-making by narrowing the field of potential decisions for each primary care visit. This patient-centered care model has the potential to significantly improve the design of primary care systems responsible for providing patient-centered care and offers an innovative approach to improving the care of increasingly complex patients.

2.5. The role of health IT

When patients have multiple diagnoses, symptoms, and concerns, it is clearly not possible to elicit preferences, discuss options, and plan goals for each of a dozen or more separate decisions during each face-to-face visit. Moreover, many of these are chronic or recurrent rather than discrete one-time choices. Because time constraints are the major barrier to negotiated partnerships and shared decision-making, simple tools to facilitate patient–provider communication may help to overcome these time constraints in primary care. The Chronic Care Model, a highly successful overarching model for chronic care, emphasizes the need to create “informed, activated patients” and “prepared, pro-active” care teams through innovative delivery system re-design.45 We build on this model of productive visit interactions by extending the original visit interaction concept to include IT-supported pre-visit prioritization by patients. Novel applications of health IT tools present an especially promising avenue to achieving this goal. By leveraging the ability to collect actionable patient data before the visit and ensuring that these data are easily available during the visit, asynchronous use of health IT tools has the potential to improve the quality of care interactions for complex patients. In this model, technology supplements care rather than substituting for care.

2.6. Applying the pre-visit prioritization model to the patient vignette

We began this review by presenting the fairly typical case of a complex patient with multiple health-related concerns. Here we envision how the visit interaction might proceed in the “usual care” setting and with IT-supported pre-visit prioritization.

2.6.1. Usual care

Patient-related issues alluded to in the vignette included back pain, sleep disorder, and changes related to sexual activity. As described earlier, pain in older patients frequently interferes with healthy behaviors,13 and concerns related to sleep and sexual activity are frequently not discussed.24–27 While patients prioritize symptoms, we know that providers are trained to focus on high-risk conditions, and we can predict that this patient’s provider may be particularly concerned about his smoking and she may wish to make medication changes to address his elevated blood pressure, glycemia, and/or hypercholesterolemia. With at least 8 or 9 issues identified in this vignette, it would not be a surprise if several if not the majority of them remain un-discussed or unaddressed by the end of the visit.46 Moreover, the evidence we presented on discordance suggests that if the provider does not acknowledge the patient’s most pressing concerns, she may be less successful in her efforts to convince him to stop smoking47 or make changes to his medical regimen.

2.6.2. IT-supported pre-visit prioritization

In our conceptual model, the time before the visit is an opportunity to prepare for and optimize the up-coming patient–provider interaction. We envision an IT tool, such as an on-line portal linked to the medical record that the patient can access prior to his visit. Integrated care systems are increasingly including such on-line portals as tools for communicating with patients. Prior work focused on diabetes has shown that patients who review their current diabetes goals are more likely to have medication changes if above goal at their next visit.48 Generalizing this disease-focused approach to the complex patient, we can envision a pre-visit prioritization tool that our vignette patient could use to prioritize and highlight the severe impact of his back pain and his anxiety about erectile dysfunction given his new romantic relationship. We hypothesize that if his provider knew of these 2 concerns prior to entering the exam room, she could directly and efficiently address them while leaving sufficient time to then turn to managing his more chronic conditions. Indeed, this type of concordant communication would be expected to improve the trust and rapport of the relationship. This strengthened relationship could in turn, for example, help catalyze more effective smoking cessation counseling at the next visit.

2.7. Challenges to the patient-centered pre-visit prioritization model

Prioritization may be more difficult for some patients, based on their level of health literacy, the complexity of their medical and socio-economic challenges, and their degree of willingness to engage in their own care. Patients may embrace efforts to engage them actively in helping identify and negotiate priorities to varying degrees based on their age and personal or cultural backgrounds leading to different attitudes towards care.49 Thus, efforts to support patient prioritization must acknowledge that not all patients will want to take an active role. Nonetheless, even among less engaged patients, identifying their primary concerns remains a key step when planning care and can lead to improved patient satisfaction, even among patients who report not wanting to be involved in decisions.50 In addition, the technology to enable pre-visit prioritization may also present a barrier, although national surveys continue to show rapidly increasing rates of Internet usage by all segments of society, including the elderly and lower income adults. In our vignette we described an on-line portal, but other options should also be developed and evaluated, such using a waiting room computer or touch-screen pad. Other patients could benefit from having clinical staff call them by phone to identify their priorities for the upcoming visit.

Challenges to this model of care may also exist from the provider’s side, as there may be some reluctance to address certain issues (e.g., chronic pain, depression) when there is a lack of available resources to help the provider effectively manage the problem. Explicitly eliciting non-medical concerns before the visit, however, may provide sufficient opportunity to arrange for other staff (e.g. social workers) to communicate with the patient. Our patient–provider dyad model can also be extended to include the patient’s family and community, as appropriate.51

Finally, although we focus in this review on the importance of the primary care visit as a critical opportunity to catalyze changes in care, patients spend the vast majority of their time not at doctor’s offices. Moreover, patients’ successful self-management of their chronic conditions (taking prescribed medications, self-monitoring, eating a healthy diet, engaging in physical activity) is essential to improved outcomes. To be successful, the shared priorities discussed at the visit must be implemented by the patient through their self-management activities.

3. Summary

The primary care of complex patients often falls short of ideal care. Innovative approaches to patient-centered care for complex patients are needed to address these shortcomings. Given the limited time during primary care visits to address the extensive list of patient- and provider-generated issues, interventions that can help patients and providers prioritize the top issues to address at a given visit provide a novel approach to the problem of patient complexity. Within this conceptual framework for re-designing care interactions, health IT tools may serve a potentially valuable role for helping to create productive interactions between prepared patients and informed providers by helping complex patients identify their top priorities prior to an upcoming primary care visit.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant numbers P30DK092926, NIDDK R01 DK099108 and P30DK092924 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and by the Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California.

References

- 1.Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA, et al. Multiple chronic conditions: prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(suppl 3):391–395. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0322-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider KM, O’Donnell BE, Dean D. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions in the United States’ medicare population. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2009;7:82. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Field TS, Gurwitz JH, Harrold LR, et al. Risk factors for adverse drug events among older adults in the ambulatory setting. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52(8):1349–1354. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peek CJ, Baird MA, Coleman E. Primary care for patient complexity, not only disease. Families, Systems & Health. 2009;27(4):287–302. doi: 10.1037/a0018048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reuben DB, Tinetti ME. Goal-oriented patient care—an alternative health outcomes paradigm. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(9):777–779. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1113631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant RW, Wexler DJ, Ashburner JM, Hong CS, Atlas SJ. Characteristics of complex patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus according to their primary care physicians. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012;172(10):821–823. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbo ED, Zhang Q, Zelder M, Huang ES. The increasing number of clinical items addressed during the time of adult primary care visits. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(12):2058–2065. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0805-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ostbye T, Yarnall KS, Krause KM, Pollak KI, Gradison M, Michener JL. Is there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care? Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3(3):209–214. doi: 10.1370/afm.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant RW, Ashburner JM, Hong CC, Chang Y, Barry MJ, Atlas SJ. Defining patient complexity from the primary care physician’s perspective: a cohort study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011;155(12):797–804. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-12-201112200-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tai-Seale M, McGuire TG, Zhang W. Time allocation in primary care office visits. Health Services Research. 2007;42(5):1871–1894. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00689.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shires DA, Stange KC, Divine G, et al. Prioritization of evidence-based preventive health services during periodic health examinations. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;42(2):164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaudhry SI, Berlowitz DR, Concato J. Do age and comorbidity affect intensity of pharmacological therapy for poorly controlled diabetes mellitus? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(7):1214–1216. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krein SL, Hofer TP, Holleman R, Piette JD, Klamerus ML, Kerr EA. More than a pain in the neck: how discussing chronic pain affects hypertension medication intensification. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(8):911–916. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1020-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerr EA, Heisler M, Krein SL, et al. Beyond comorbidity counts: how do comorbidity type and severity influence diabetes patients’ treatment priorities and self-management? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(12):1635–1640. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0313-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parchman ML, Romero RL, Pugh JA. Encounters by patients with type 2 diabetes —complex and demanding: an observational study. Annals of Family Medicine. 2006;4(1):40–45. doi: 10.1370/afm.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofer TP, Zemencuk JK, Hayward RA. When there is too much to do: how practicing physicians prioritize among recommended interventions. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19(6):646–653. doi: 10.1007/s11606-004-0058-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiner SJ, Schwartz A, Weaver F, et al. Contextual errors and failures in individualizing patient care: a multicenter study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2010;153(2):69–75. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-2-201007200-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Iannone L. Primary care clinicians’ experiences with treatment decision making for older persons with multiple conditions. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171(1):75–80. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294(6):716–724. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tinetti ME, McAvay GJ, Fried TR, et al. Health outcome priorities among competing cardiovascular, fall injury, and medication-related symptom outcomes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56(8):1409–1416. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01815.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrow AS, Haidet P, Skinner J, Naik AD. Integrating diabetes self-management with the health goals of older adults: a qualitative exploration. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;72(3):418–423. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fried TR, McGraw S, Agostini JV, Tinetti ME. Views of older persons with multiple morbidities on competing outcomes and clinical decision-making. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56(10):1839–1844. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bayliss EA, Ellis JL, Steiner JF. Seniors’ self-reported multimorbidity captured biopsychosocial factors not incorporated into two other data-based morbidity measures. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62(5):550–557. e551. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindau ST, Tang H, Gomero A, et al. Sexuality among middle-aged and older adults with diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes: a national, population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(10):2202–2210. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sudore RL, Karter AJ, Huang ES, et al. Symptom burden of adults with type 2 diabetes across the disease course: diabetes & aging study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2012;27(12):1674–1681. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2132-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Resnick HE, Redline S, Shahar E, et al. Diabetes and sleep disturbances: findings from the Sleep Heart Health Study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):702–709. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trief PM, Ploutz-Snyder R, Britton KD, Weinstock RS. The relationship between marital quality and adherence to the diabetes care regimen. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27(3):148–154. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2703_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heisler M, Vijan S, Anderson RM, Ubel PA, Bernstein SJ, Hofer TP. When do patients and their physicians agree on diabetes treatment goals and strategies, and what difference does it make? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18 (11):893–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zulman DM, Kerr EA, Hofer TP, Heisler M, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Patient–provider concordance in the prioritization of health conditions among hypertensive diabetes patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25(5):408–414. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1232-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Street RL, Jr, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician–patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;74(3):295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zolnierek KB, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Medical Care. 2009;47(8):826–834. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piette JD, Heisler M, Wagner TH. Cost-related medication underuse: do patients with chronic illnesses tell their doctors? Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164 (16):1749–1755. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.16.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piette JD, Heisler M, Krein S, Kerr EA. The role of patient-physician trust in moderating medication nonadherence due to cost pressures. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165(15):1749–1755. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.15.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGinnis B, Olson KL, Magid D, et al. Factors related to adherence to statin therapy. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2007;41(11):1805–1811. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayes RP, Bowman L, Monahan PO, Marrero DG, McHorney CA. Understanding diabetes medications from the perspective of patients with type 2 diabetes: prerequisite to medication concordance. Diabetes Educator. 2006;32(3):404–414. doi: 10.1177/0145721706288182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heisler M. Actively engaging patients in treatment decision making and monitoring as a strategy to improve hypertension outcomes in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2008;117(11):1355–1357. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.764514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bohlen K, Scoville E, Shippee ND, May CR, Montori VM. Overwhelmed patients: a videographic analysis of how patients with type 2 diabetes and clinicians articulate and address treatment burden during clinical encounters. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(1):47–49. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox K, Britten N, Hooper R, White P. Patients’ involvement in decisions about medicines: GPs’ perceptions of their preferences. The British Journal of General Practice. 2007;57(543):777–784. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gravel K, Legare F, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Implementation Science: IS. 2006;1:16. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Street RL, Jr, Haidet P. How well do doctors know their patients? Factors affecting physician understanding of patients’ health beliefs. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2011;26(1):21–27. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1453-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang ES, Gorawara-Bhat R, Chin MH. Self-reported goals of older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53 (2):306–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barry CA, Bradley CP, Britten N, Stevenson FA, Barber N. Patients’ unvoiced agendas in general practice consultations: qualitative study. BMJ. 2000;320 (7244):1246–1250. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beverly EA, Ganda OP, Ritholz MD, et al. Look who’s (not) talking: diabetic patients’ willingness to discuss self-care with physicians. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(7):1466–1472. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lafata JE, Morris HL, Dobie E, Heisler M, Werner RM, Dumenci L. Patient-reported use of collaborative goal setting and glycemic control among patients with diabetes. Patient Education and Counseling. 2013;92(10):94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. The Milbank Quarterly. 1996;74(4):511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grant RW, Buse JB, Meigs JB. Quality of diabetes care in U.S. academic medical centers: low rates of medical regimen change. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(2):337–442. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.2.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feldman MD. All in a day’s work: establishing rapport, making decisions, reducing disparities. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2012;27(10):1231–1232. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2187-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grant RW, Wald JS, Schnipper JL, et al. Practice-linked online personal health records for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(16):1776–1782. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levinson W, Kao A, Kuby A, Thisted RA. Not all patients want to participate in decision making. A national study of public preferences. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20(6):531–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.04101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Golin CE, DiMatteo MR, Gelberg L. The role of patient participation in the doctor visit. Implications for adherence to diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 1996;19 (10):1153–1164. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.10.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Affairs. 2013;32(2):223–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]