Abstract

A major goal in harmful algal bloom (HAB) research has been to identify mechanisms underlying interannual variability in bloom magnitude and impact. Here the focus is on variability in Alexandrium fundyense blooms and paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) toxicity in Maine, USA, over 34 years (1978 – 2011). The Maine coastline was divided into two regions -eastern and western Maine, and within those two regions, three measures of PSP toxicity (the percent of stations showing detectable toxicity over the year, the cumulative amount of toxicity per station measured in all shellfish (mussel) samples during that year, and the duration of measurable toxicity) were examined for each year in the time series. These metrics were combined into a simple HAB Index that provides a single measure of annual toxin severity across each region. The three toxin metrics, as well as the HAB Index that integrates them, reveal significant variability in overall toxicity between individual years as well as long-term, decadal patterns or regimes. Based on different conceptual models of the system, we considered three trend formulations to characterize the long-term patterns in the Index – a three-phase (mean-shift) model, a linear two-phase model, and a pulse-decline model. The first represents a “regime shift” or multiple equilibria formulation as might occur with alternating periods of sustained high and low cyst abundance or favorable and unfavorable growth conditions, the second depicts a scenario of more gradual transitions in cyst abundance or growth conditions of vegetative cells, and the third characterizes a ”sawtooth” pattern in which upward shifts in toxicity are associated with major cyst recruitment events, followed by a gradual but continuous decline until the next pulse. The fitted models were compared using both residual sum of squares and Akaike's Information Criterion. There were some differences between model fits, but none consistently gave a better fit than the others. This statistical underpinning can guide efforts to identify physical and/or biological mechanisms underlying the patterns revealed by the HAB Index. Although A. fundyense cyst survey data (limited to 9 years) do not span the entire interval of the shellfish toxicity records, this analysis leads us to hypothesize that major changes in the abundance of A. fundyense cysts may be a primary factor contributing to the decadal trends in shellfish toxicity in this region. The HAB Index approach taken here is simple but represents a novel and potentially useful tool for resource managers in many areas of the world subject to toxic HABs.

Keywords: Alexandrium fundyense, harmful algal blooms, HABs, PSP, HAB Index

1 Introduction

Harmful algal blooms (HABs) are a common threat to public health and coastal economies throughout the world. In many affected areas, the phenomena are regular, annual events, but in other cases, occur sporadically. Blooms vary in frequency, geographic extent, duration, shellfish toxicity, and cell abundance. This multifaceted interannual variability poses significant challenges to management programs that seek to protect fisheries resources and public health, and as a result, it is often necessary to monitor shellfish and phytoplankton over broad areas and long intervals of time, even in years when PSP outbreaks are spatially and/or temporally limited.

A major goal for those conducting HAB research has therefore been to identify the mechanisms underlying interannual variability in bloom magnitude and impact in a given region. In some cases, these efforts examined atmosphere/ocean forcings such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO; Maclean, 1989; Usup and Azanza, 1998; Azanza and Taylor, 2001; Moore et al., 2008), or longer-term cycles, such as North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO; e.g. Alvarez-Salgado et al., 2003), and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO; Erickson and Nishitani, 1985; Trainer et al., 2003). White (1987) suggested a possible correlation between periods of greatest shellfish toxicity in the Bay of Fundy (BOF) due to A. fundyense blooms and a cyclical phenomenon such as an 18.6-year lunar cycle. Martin and Richard (1996) also examined data from the BOF using five-, seven-, eight-, and ten-year moving average statistical techniques. No clear cycles were observed, although other trends were suggested from the 51-year data set. These included periods of higher toxicity in the mid-1940s, the early ‘60s, the late ‘70s, and mid-‘90s. The underlying causes of these toxicity regimes were not specified.

This study examines interannual variability in A. fundyense2 blooms and the associated PSP toxicity in the Gulf of Maine (GOM). Historically, toxicity was largely restricted to eastern Maine and the BOF until 1972, when a massive, visible red tide of A. fundyense caused toxicity in many western gulf areas for the first time (Hartwell, 1975). Since 1972, PSP toxicity has been a recurrent problem throughout the region, including western gulf waters, and is responsible for widespread shellfish harvesting closures and significant economic losses virtually every year (Shumway et al., 1988; Jin et al., 2008). Since the major 1972 outbreak, annual toxicity has varied extensively within the region, both in geographic extent and magnitude (McGillicuddy et al., 2005b, 2011; Luerssen et al., 2005; Thomas et al., 2010; Horecka et al., this issue; Kleindinst et al., this issue).

An important feature in A. fundyense population dynamics and toxin production is the hypnozygote or resting cyst that is part of this organism's life history (Anderson, 1998). These dormant cells fall from the water column during blooms, accumulating in the sediments (Anderson and Wall, 1978; Anderson et al., 2005c) and near-bottom waters (Kirn et al., 2005; Pilskaln et al., this issue; Butman et al., this issue) where they remain until conditions are suitable for germination. Given the temperate climate of the GOM region and the virtual absence of A. fundyense cells in the water column and rare occurrence of toxins in shellfish during winter, blooms are heavily dependent on resting cysts for overwintering and eventual bloom inoculation and recurrence. It is thus important to consider changes in cyst abundance in this study of interannual variability in toxicity.

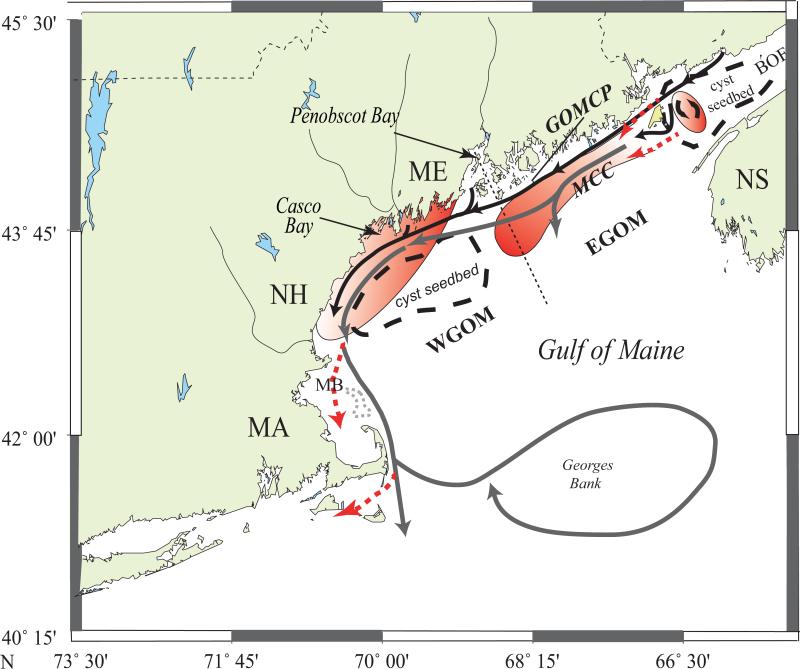

It is also important to understand the regional bloom dynamics and links to coastal hydrography and cyst “seedbeds”. Conceptual models of A. fundyense bloom dynamics in the GOM have been provided by Anderson et al. (2005c) and McGillicuddy et al. (2005a). Key features are two cyst seedbeds - one in the BOF, and the other in mid-coast Maine offshore of Casco and Penobscot Bays (Fig. 1; Anderson et al., 2005c; Anderson et al., this issue). Cysts germinate from the BOF seedbed, causing recurrent A. fundyense blooms within a retentive eddy at the mouth of the Bay that are self-seeding with respect to future outbreaks in that area (White and Lewis, 1982; Aretxabaleta et al., 2008, 2009; Martin et al., this issue). Some cells escape the retention zone and enter the eastern segment of the Maine Coastal Current (MCC) where they bloom. Some of these are advected into the western GOM, while others undergo sexual reproduction and fall to the bottom as cysts that accumulate in a feature hereafter termed the mid-coast Maine seedbed near Casco and Penobscot Bays (Anderson et al., 2005c; Anderson et al., this issue). The mid-coast Maine cysts (combined with vegetative cells from upstream populations) contribute to blooms that cause toxicity in western portions of the gulf and possibly offshore waters as well.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model map of Alexandrium fundyense regional blooms in the Gulf of Maine. Areas enclosed with dashed lines denote cyst seedbeds that provide inoculum cells. Major current systems are shown with solid arrows (black = Maine Coastal Current (MCC); grey = Gulf of Maine Coastal Plume (GMCP; Keafer et al., 2005). Possible A. fundyense transport pathways (separate from the major current systems) are shown with dashed red arrows. Red-shaded areas represent regions of growth and transport of motile A. fundyense cells. Modified from Anderson et al. (2005c). The dividing line between WGOM and EGOM is shown at Penobscot Bay, as described in the text. Abbreviations: MCC –Maine Coastal Current; GOMCP – Gulf of Maine Coastal Plume; MB – Massachusetts Bay; BOF – Bay of Fundy; MA – Massachusetts; NH – New Hampshire; ME – Maine; NS – Nova Scotia.

There are many factors that can regulate bloom size and the extent to which cells are delivered to nearshore shellfish, including temperature, sunlight, nutrients, rainfall, and wind speed and direction. It is thus not surprising that the geographic extent and magnitude of PSP toxicity has been highly variable over the years that it has been monitored in Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts (Shumway et al., 1988; Bean et al., 2005; Kleindinst et al., this issue). Here we describe a study that uses a simple approach to investigate interannual variability in Maine shellfish toxicity. We collapsed 34 years of shellfish toxicity data from weekly sampling at 160 stations in Maine into a novel “HAB Index” that can be used to characterize the severity of PSP toxicity in a given year. We use this Index to identify decade-level eras or regimes in toxicity in two Maine subregions. Given the significant relationship between cyst abundance and the magnitude of subsequent blooms established in other studies (McGillicuddy et al., 2011; Anderson et al., this issue), we hypothesize that the decadal variability observed in Maine toxicity may reflect differences in regional cyst abundance, although we recognize that this is based on a limited cyst abundance data set and will thus require further testing.

2 Methods

2.1 Blooms and shellfish toxicity

For the purposes of this paper, we have adopted an operational definition of the word “bloom” to mean that the concentration of A. fundyense vegetative cells in contact with nearshore shellfish populations is sufficient to cause detectable toxicity (≥40 μg saxitoxin equivalents (STX eq.) per 100 g of shellfish tissue). We do this because the metrics used to calculate the HAB Index all depend on shellfish toxicity measurements.

Throughout the years of this study, the state of Maine measured shellfish toxicity weekly at 160 stations along the coast during months that have a risk of PSP toxicity (generally March – November), and closed harvesting when PSP toxin levels exceeded the action limit of 80 μg STX eq. 100g−1 shellfish meat. The limit of detection for the mouse bioassay is ~ 40 μg STX eq. 100g−1 shellfish meat. Eleven species of shellfish were tested, with more than 3000 samples analyzed annually. To reduce potential bias introduced by species-specific toxin uptake and depuration rates (Bricelj and Shumway, 1998), we focus our HAB Index analysis on toxicity in blue mussels – Mytilus edulis.

A PSP toxin-monitoring program has existed in the state since 1958, but in early years, the number of stations sampled was limited and the schedule of sampling was sporadic (Hurst, 1975; Shumway et al., 1988). It is only since 1977 that a consistent set of stations has been monitored on a regular basis along the entire coast. We thus have a 35-year dataset from 160 stations that extends to 2011. Note, however, that in 1977, there was an irregular sampling strategy, in that no Mytilus samples were taken in eastern Maine until the end of September that year. Thus, 1977 is not included in our analysis and the total dataset spans 34 years. Throughout this long-term, state monitoring program, PSP toxins in shellfish were measured using the AOAC mouse bioassay (Association of Official Analytical Chemists, 1980).

2.2 Maine subregions

Hereafter, “eastern Maine” is used to describe the portion of the Maine coastline extending from the Canadian border near the mouth of the BOF to the midpoint of Penobscot Bay (Fig. 1). The “western Maine” subregion extends from Penobscot Bay to the New Hampshire border. Note that this terminology is tied to the coastline of a single state, whereas other GOMTOX studies that address the waters of the GOM have used EGOM to describe the subregion of the Gulf extending from the BOF to Penobscot Bay, and WGOM to describe the subregion from Penobscot Bay to Massachusetts waters (e.g. Anderson et al., this issue). The rationale for the regional separation at Penobscot Bay is given below.

2.3 The Maine HAB Index

The HAB Index is calculated from records of PSP toxicity in M. edulis from 160 monitoring stations in Maine over the interval 1978-2011 (Maine Department of Marine Resources; Table 1). The first parameter or metric in the Index is the percent of stations within each subregion (i.e., eastern and western Maine) where detectable toxicity (i.e., >40 μg STX eq. 100g−1) was measured for that year. These percentages were grouped into 5 equal bins (i.e., 0-20%, 21-40%, etc.), and each bin assigned a number from 1 to 5. For the second parameter, toxicity levels measured in M. edulis at each sampling station and time were summed over the bloom season for all stations for each subregion, and then that total is divided by the number of stations in that subregion and binned into ranges of 500 μg STX eq. 100g−1 increments that are then assigned a numerical value from 1 to 5. Thus “cumulative toxicity per station” is the second parameter in the Index. Normalizing the cumulative toxicity to the number of stations in a subregion allows the western and eastern subregions of Maine to be directly compared, as they have different numbers of stations (90 and 70 respectively). The final Index parameter is the duration of detectable mussel toxicity measured at stations affected by the widespread, coastal A. fundyense blooms – i.e., excluding Lumbos Hole, Maine, an inland, isolated site where blooms are initiated and develop in situ. The parameter represents the interval between the first detectable toxicity at any station in either subregion and the last measurable toxicity at any station within either subregion, with durations (total days) binned and assigned a numerical value between 1 and 5.

Table 1.

Metrics of the Maine HAB Index (see Methods sec. 2.3).

| Bin # | % of toxic stations | Cumulative toxicity per station (μg STX eq. 100g−1 shellfish meat) | Duration of toxicity (days) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0-20 | 0-500 | 0-50 |

| 2 | 21-40 | 501-1,000 | 51-100 |

| 3 | 41-60 | 1,001-1,500 | 101-150 |

| 4 | 61-80 | 1,501-2,000 | 151-200 |

| 5 | 81-100 | >2,000 | >200 |

Numerical values (bin numbers) for these three parameters (Table 1) are then summed for each year to give a single Index value for the western and eastern regions for that year (Table 2). The Index can thus vary between 3 and 15. Note that on occasion, subjective decisions were made on some of these parameters at some stations (such as when late-season toxicity persisted through the winter in the absence of vegetative cells, thereby affecting the apparent start date of toxicity the following year, and thus the duration calculations). Details of this type, as well as a narrative on how different factors might affect the Index calculations each year are given in online Supplementary Materials. Additional information about the annual PSP closures is given in Kleindinst et al. (this issue) and in the associated Supplementary Materials for that paper.

Table 2.

The Maine HAB Index and constituent metrics of toxicity.

| Year | % of Toxic Stations (West) | % of Toxic Stations (East) | Cumulative toxicity per station (West) | Cumulative toxicity per station (East) | Duration (West) | Duration (East) | Total Index (West) | Total Index (East) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | 102 | 43 | 4116 | 399 | 206 | 94 | 15 | 6 |

| 1979 | 91 | 13 | 1889 | 118 | 162 | 97 | 13 | 4 |

| 1980 | 91 | 64 | 4134 | 1096 | 206 | 262 | 15 | 12 |

| 1981 | 92 | 26 | 2081 | 397 | 143 | 198 | 13 | 7 |

| 1982 | 68 | 36 | 755 | 343 | 149 | 135 | 9 | 6 |

| 1983 | 69 | 29 | 1105 | 355 | 126 | 140 | 10 | 6 |

| 1984 | 83 | 41 | 1752 | 401 | 106 | 114 | 12 | 7 |

| 1985 | 31 | 30 | 273 | 416 | 112 | 127 | 6 | 6 |

| 1986 | 92 | 31 | 5757 | 1015 | 134 | 195 | 13 | 9 |

| 1987 | 63 | 20 | 804 | 130 | 177 | 150 | 10 | 5 |

| 1988 | 73 | 33 | 823 | 192 | 96 | 114 | 8 | 6 |

| 1989 | 89 | 46 | 1769 | 778 | 130 | 136 | 12 | 8 |

| 1990 | 77 | 30 | 573 | 374 | 106 | 134 | 9 | 6 |

| 1991 | 52 | 27 | 160 | 182 | 92 | 65 | 6 | 5 |

| 1992 | 30 | 30 | 48 | 126 | 70 | 134 | 5 | 6 |

| 1993 | 59 | 33 | 533 | 723 | 72 | 134 | 7 | 7 |

| 1994 | 34 | 29 | 59 | 144 | 37 | 58 | 4 | 5 |

| 1995 | 40 | 31 | 123 | 509 | 59 | 93 | 5 | 6 |

| 1996 | 10 | 11 | 7 | 25 | 63 | 79 | 4 | 4 |

| 1997 | 20 | 9 | 26 | 7 | 24 | 22 | 3 | 3 |

| 1998 | 24 | 20 | 86 | 29 | 51 | 50 | 5 | 3 |

| 1999 | 6 | 10 | 4 | 20 | 24 | 58 | 3 | 4 |

| 2000 | 59 | 4 | 433 | 6 | 52 | 56 | 6 | 4 |

| 2001 | 9 | 47 | 9 | 322 | 72 | 84 | 4 | 6 |

| 2002 | 22 | 21 | 35 | 54 | 87 | 92 | 5 | 5 |

| 2003 | 36 | 63 | 96 | 980 | 164 | 123 | 7 | 9 |

| 2004 | 53 | 77 | 256 | 2112 | 148 | 156 | 7 | 13 |

| 2005 | 72 | 54 | 1374 | 527 | 114 | 119 | 10 | 8 |

| 2006 | 89 | 50 | 529 | 230 | 96 | 103 | 9 | 7 |

| 2007 | 68 | 43 | 158 | 264 | 107 | 104 | 8 | 7 |

| 2008 | 71 | 87 | 412 | 1470 | 77 | 142 | 7 | 11 |

| 2009 | 100 | 94 | 1946 | 3379 | 140 | 141 | 12 | 13 |

| 2010 | 32 | 66 | 65 | 869 | 92 | 171 | 5 | 10 |

| 2011 | 72 | 57 | 629 | 450 | 77 | 134 | 8 | 7 |

2.4 Statistical analyses

Differences in the onset, duration, and termination of PSP toxicity were compared between regions with a t-test performed using JMP 8.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), with a significance level of α=0.05. Onset and termination data were square-transformed and the cumulative toxicity data were log-transformed to improve normality and meet homoscedasticity. These transformations produced homoscedastic data, and all but two datasets were normally distributed (EGOM, onset; WGOM, termination). Duration data did not require transformation.

Time series data for the HAB Index were analyzed to characterize changes in the HAB Index over the 34-year interval spanned by this study. Three different statistical models were fitted to the HAB Index time-series: a two-phase linear model, a mean-shift model, and a pulse-decline model. The goodness of fit for each model was measured by the residual sum of squares (RSS) for each data set, and the first two models were compared using Akaike's Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1974) to determine which analysis best described temporal trends in toxicity. Due to the parameter constraints of the third model, it was not possible to include it in the AIC comparison. For these analyses, the eastern and western regions were examined separately and together. Model formulations are described in detail below.

Let Yt, t = 1, 2, ..., n, be the time series of the HAB Index for a specific region. A general statistical model for this time series is:

| (1) |

where μt is the unknown time-varying mean or trend and εt is a normal error with mean 0 and unknown variance σ2. Three trend models were considered. For the mean-shift model:

| (2) |

Under this model, the mean of the HAB Index shifts between three levels at unknown change-points τ1 and τ2. This model represents a “regime shift” or multiple equilibria formulation as might occur with alternating periods of sustained high and low cyst abundance or favorable and unfavorable cell growth conditions.

For the two-phase model:

| (3) |

where Iτ(t) = 0 for t < τ and Iτ(t) = 1 for t ≥ τ. Under this model, the HAB index exhibits a linear trend with slope β1 through unknown time τ after which the slope changes to β1 + β2. This model depicts a scenario of more gradual transitions in cyst abundance or growth conditions.

For the pulse-decline model, the HAB index exhibits a linear decline with pre-change slope β1 through unknown time τ, an upward shift at time τ + 1, followed by a post-change linear decline with slope γ1 through time n:

| (4) |

with:

| (5) |

These parameter constraints ensure that the model has the hypothesized ”sawtooth” pattern in which upward shifts in toxicity are associated with major cyst deposition events, followed by a gradual but continuous decline until the next pulse.

The mean shift model contains a total of 5 unknown trend parameters – μ(1), μ(2), μ(3), τ1, τ2 - and the error variance σ2. The two-phase model contains 4 unknown trend parameters – β0, β1, βb, τ – and the error variance σ2. The pulse-decline model contains 5 unknown trend parameters - β0, β1, τ, γ0, γ1– and the error variance σ2.

Briefly, for fixed values of the changepoints, the maximum likelihood (ML) estimates of the trend parameters for each of these models can be found by minimizing the RSS (i.e., the sum of squared differences between the observed and fitted values of the HAB Index) and the ML estimate of σ2 is given by RSS / n where RSS is the minimized value of the RSS. In the case of the pulse-decline model, this minimization must be subject to the parameter constraints in (5). The overall ML estimates can then be found by varying the changepoints until RSS is minimized.

In statistical terminology, the three trend models are non-nested in the sense that they cannot be made equivalent by restricting parameter values. A standard approach to comparing non-nested models is through AIC. For normal models, this is given by:

| (6) |

where p is the number of parameters. The model with the smallest value of AIC is selected. When, as here, the number of observations is not much greater than the number of parameters, the small-sample version of the AIC is recommended (Burnham and Anderson, 2010). For normal models, this is given by:

| (7) |

and again the model with the smallest value of AICc selected. The imposition of parameter constraints invalidates the use of the AIC for the pulse-decline model, so it was not included in this comparison.

3 Results

3.1 Toxicity Metrics

In this study, three metrics of toxicity were examined within each Maine subregion: the percent of stations showing detectable toxicity over the year, the cumulative amount of toxin per station measured in all mussel samples during that year, and the duration of measurable toxicity (Tables 1, 2). Patterns evident in each of these time series are described in detail below. Noteworthy features of toxicity and some additional commentary are available in online Supplementary Materials.

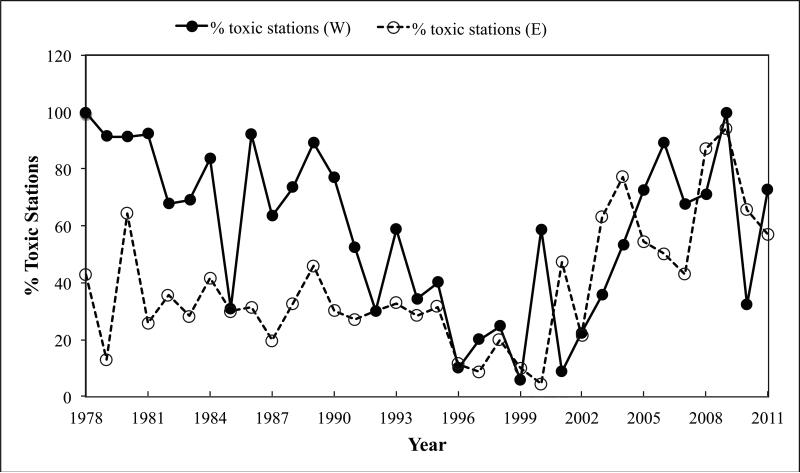

Figure 2 shows the percent of stations with detectable levels of toxicity for each year during the study period. Distinct differences are evident in the trends observed for the eastern versus western Maine stations using this metric. Of the 70 stations in eastern Maine, a fairly constant number were toxic from 1978 through 1995 (~30%). This interval was followed by a decrease in the percent of toxic stations from 1996 to approximately 2000 (generally <10 %), which in turn was followed by an increase in the mid 2000s to levels not observed previously (77 – 94 %). In western Maine, there were high percentages of toxic stations in the late 1970s and early 1980s (70– 90%) decreasing to minimum values in the late 1990s (10 - 20 %). Beginning in 2002, a rising trend in the percent of toxic stations is documented, reaching levels of 60 - 90 % of the stations each year once again.

Figure 2.

Percent of stations on the Maine coast with detectable levels of PSP mussel toxicity. Eastern Maine (open circles); western Maine (closed circles).

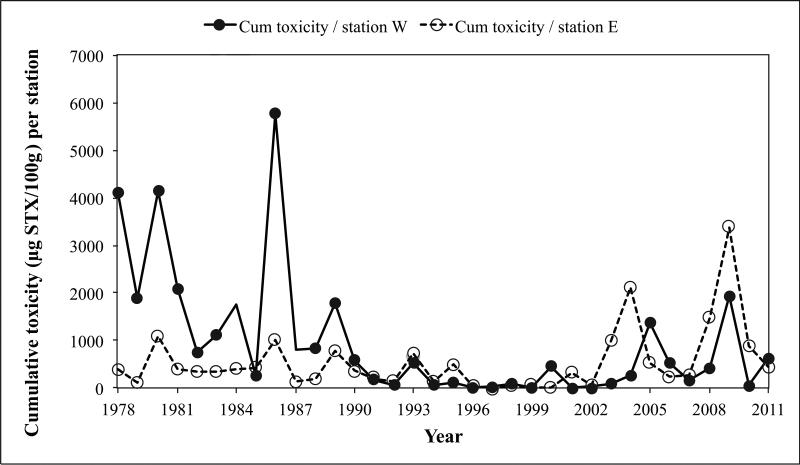

Consistent with the relatively moderate percent of toxic stations in eastern Maine from 1978 through 1995 (Fig. 2), the cumulative annual toxicity per station measured in that region was also moderate over that interval (Fig. 3). In the late 1990s, this value dropped even lower, and then increased from 2003 to 2011, though considerable variability is evident. In western Maine, the cumulative toxicity was high in the late 1970s and ’80s and low through the 1990s, with an apparent increase after 2003, again with fluctuations in recent years. On average, the cumulative toxicity per station was not significantly different between eastern and western Maine (p=0.66), although if this comparison is made over the early high toxicity period of the Index (1978-1990), western Maine stations were significantly more toxic than eastern Maine stations (p=0.0003). For the 2003-2011 interval, there was no significant difference in cumulative toxicity between west and east (p=0.1215).

Figure 3.

Cumulative toxicity per station measured in Mytilus edulis in western Maine (closed circles) and eastern Maine (open circles) for each year.

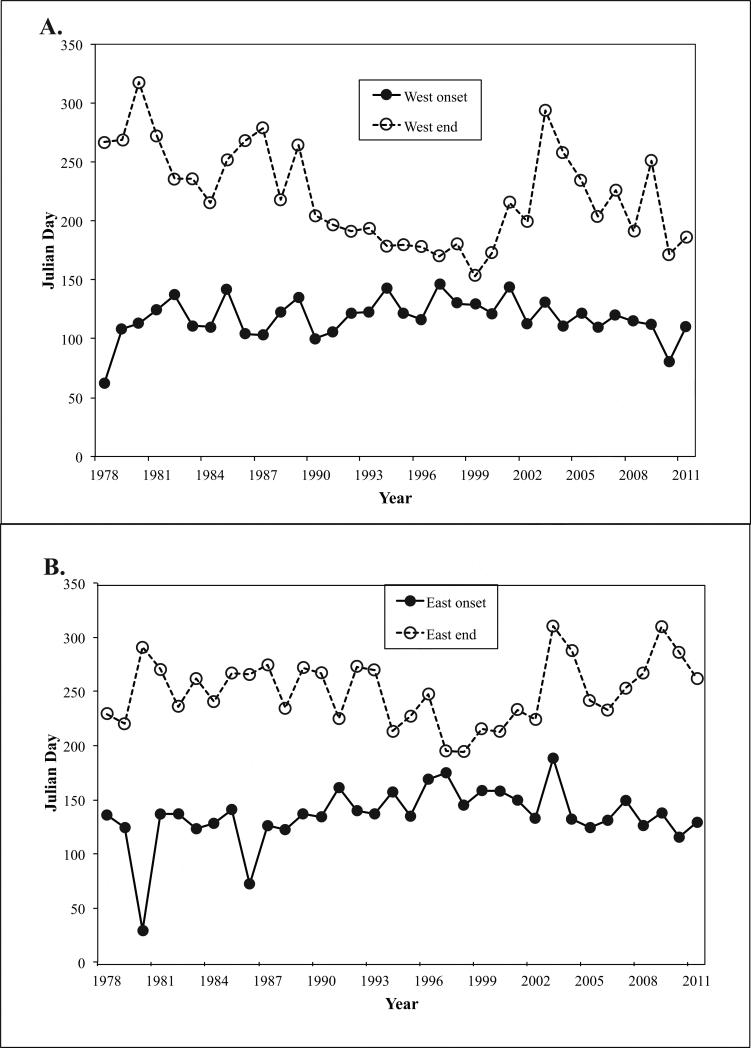

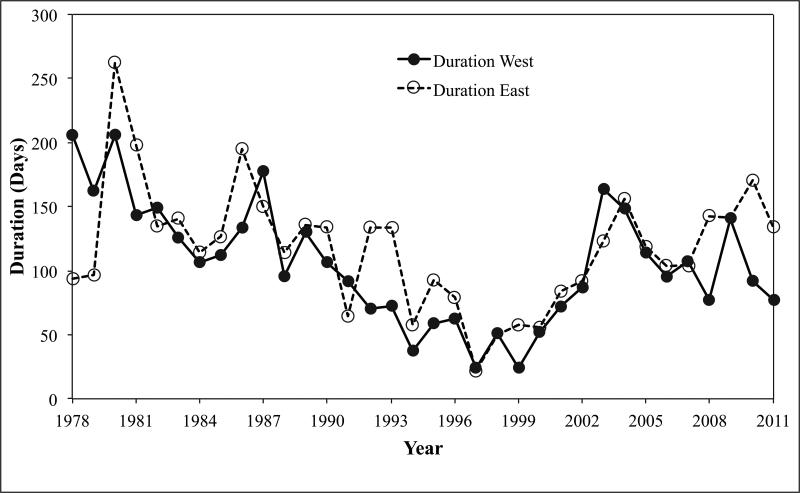

The duration of the toxic events also varied considerably through time (Figs. 4, 5). In Fig. 4, the onset and termination of toxicity are shown separately for both western and eastern Maine. The time interval between the two lines for each region indicates the duration of the outbreak for a given year. The calculated duration of detectable toxicity for each year is given in Figure 5. Once again, considerable variability is evident between individual years, but long-term trends are evident in the record. In particular, the outbreaks in the late 1970s, 1980s, and 2000s have tended to be longer than those in the 1990s, some of which were notably short. It is also apparent that toxicity began significantly earlier in western Maine (t= 3.84, d.f.=66, p=0.0003), with an average onset date of April 28 in the west versus May 15 in the east (17 days; Table 3).

Figure 4.

Onset and termination dates for toxicity detection in Maine –western Maine (A), eastern Maine (B).

Figure 5.

Duration of detectable toxicity for western (closed circles) and eastern (open circles) Maine.

Table 3.

Average onset and termination dates (± SD) and duration of PSP toxicity in eastern and western Maine

| Parameter | Date or duration |

|---|---|

| West onset | April 28 (± 17) |

| West termination | August 9 (± 42) |

| West duration (days) | 105 (± 47) |

| East onset | May 15 (± 27) |

| East termination | September 7 (± 30) |

| East duration (days) | 118 (± 48) |

The average date for termination of toxicity is also significantly earlier in western Maine than in the east (t= 3.06, d.f.=66, p=0.003), August 9 versus September 7 (Table 3). The average duration of toxicity was 105 days in the west, and 118 days in the east; however, this difference was not statistically significant (t= 1.13, d.f.=66, p=0.26).

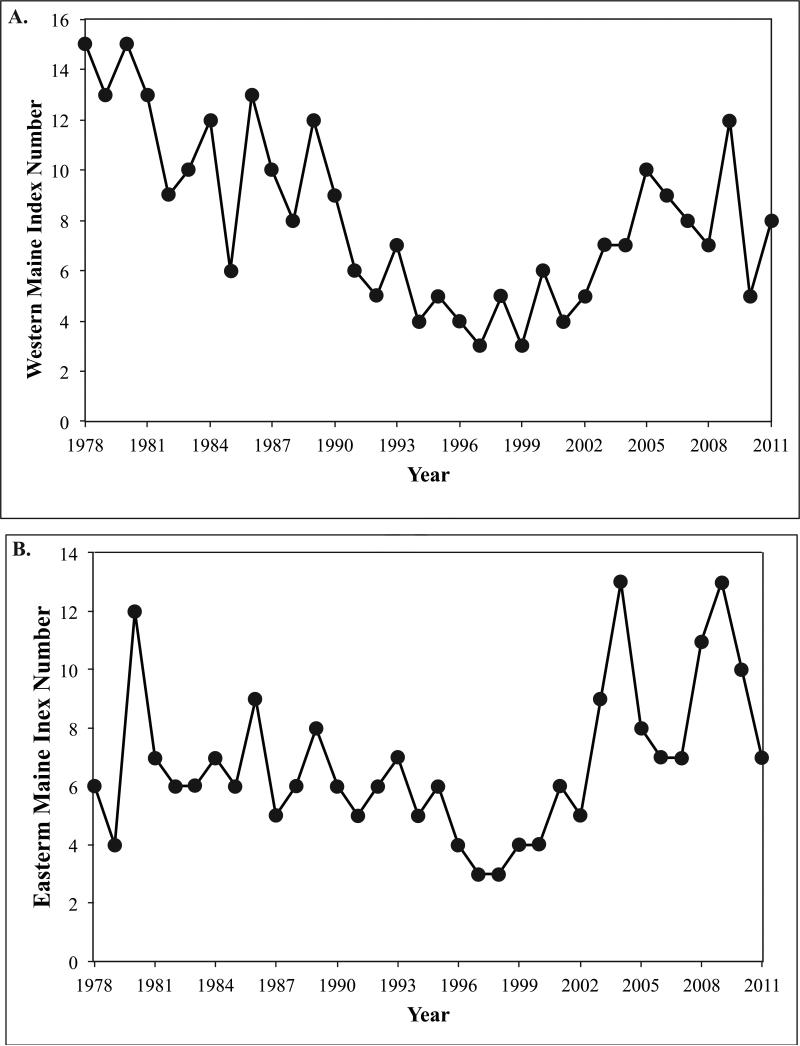

3.2 The HAB Index

Each of the toxicity metrics described above provides useful information, but it is also informative to combine these metrics into a single measure that categorizes the overall severity of PSP toxicity in Maine in a given year. This is termed the HAB Index (Fig. 6; Table 2), which reveals differences between western and eastern Maine toxicity patterns and provides a single metric of regional GOM toxicity. In the east, the Index values are lower than is the case in the west, particularly in the first 13 years of the record. Over that interval (1978 – 1990), the Index for the east averaged 6.8 (±2.0 SD), whereas in the west, it was 11.2 (±2.7). Over the entire 34 years of record, the eastern and western Indices averaged 6.8 (± 2.6) and 8.1 (± 3.5) respectively.

Figure 6.

HAB Indices for western Maine (A), eastern Maine (B), and combined (C).

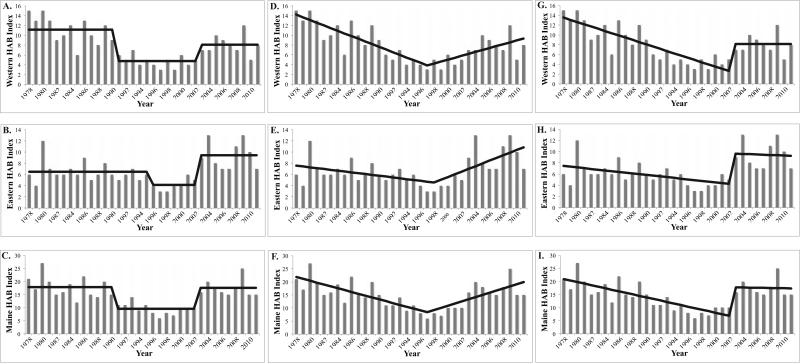

Three model formulations were considered in the analysis of trends in the HAB Index. The general form of these models is shown in Figure 7. The first was a mean-shift approach in which a constant mean changes to another mean with a distinct transition point or change point. This approach is consistent with an interpretation of the patterns shown in Figure 7A-C as representing an era of high toxicity from the late 1970s to the early 1990s, followed by an interval of consistently low toxicity until the early 2000s, and then by a new era of high toxicity. In this analysis, we constrained the mean-shift model to find two change points, with their locations estimated from the data as part of the fitting.

Figure 7.

Mean-shift (A-C), two-phase (D-F), and pulse-decline (G-I) models fitted to time series of the HAB Index for eastern and western Gulf of Maine separately, and together.

The results from fitting the mean-shift model to time series of the HAB Index for western and eastern Maine separately and together are presented in Table 4. These regions will be referred to as western Maine, eastern Maine, and western plus eastern Maine, respectively. Clearly, the results for the overall region should not be viewed as independent of those for the two subregions. Change-point analysis delineates three eras of toxicity in the HAB Index. The estimate of the earliest change point was 1990 for both western Maine and western plus eastern Maine and 1995 for eastern Maine only. Notably, the estimate of the second or later change point was 2002 for all three datasets. In Figure 7A-C, the original time series are shown along with the fitted trends from the mean-shift model.

Table 4.

Estimated parameters for mean-shift model fitted to the HAB Index time series data: mean for each interval (), change-point years (), and residual sum of squares (RSS).

| Region | RSS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Maine | 11.2 | 1990 | 4.75 | 2002 | 8.1 | 138.8 |

| Eastern Maine | 6.5 | 1995 | 4.14 | 2002 | 9.4 | 109.6 |

| Western + Eastern Maine | 17.9 | 1990 | 9.58 | 2002 | 17.6 | 336.1 |

An alternative view of the HAB Index patterns is that toxicity was high in the late 1970s, and then decreased steadily until the mid 1990s when a change point occurred, leading to an increasing trend thereafter, continuing to the present. This V-shaped scenario was modeled using the two-phase model with a single change point. Results are shown in Figures 7D-F and Table 5. In this case, the estimates of the single change point are very close for the two Maine subregions: 1997 for western Maine and western plus eastern Maine, and 1998 for eastern Maine. In Figure 7D-F, the original time series are again shown along with the fitted trends from the two-phase model.

Table 5.

Estimated parameters for two-phase model fitted to the HAB Index time series data: trend parameters , change-point year , and residual sum of squares RSS.

| Region | τ | RSS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Maine | 14.7 | −0.54 | 1997 | 0.94 | 121.5 |

| Eastern Maine | 7.7 | −0.15 | 1998 | 0.63 | 135.3 |

| Western + Eastern Maine | 22.6 | −0.71 | 1997 | 1.54 | 363.2 |

The third model depicts a scenario in which pulses in toxicity are linked to major cyst deposition events, after which toxicity gradually declines. For all three datasets the year 2002 was selected as the single fixed change point estimate τ indicating the timing of an upward shift in toxicity. The pre-change slope β1 for western and eastern Maine was −0.45 and −0.13, respectively, while the post-change slope γ1 was zero for western Maine and −0.05 for eastern Maine. Results are shown in Figures 7G-I and Table 6.

Table 6.

Estimated parameters for pulse-decline model fitted to the HAB Index time series data: trend parameters , change-point year , and residual sum of squares RSS.

| Region | RSS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Maine | 14.0 | −0.45 | 2002 | 8.1 | 0 | 127.0 |

| Eastern Maine | 7.6 | −0.13 | 2002 | 9.6 | −0.05 | 114.4 |

| Western + Eastern Maine | 21.5 | −0.06 | 2002 | 17.8 | −0.05 | 322.1 |

The goodness of fit for each model was measured by the residual sum of squares (RSS) for each data set. Based on minimal RSS values, the mean-shift model was the best fit for eastern Maine, the two-phase model the best fit for western Maine, and the pulse-decline model best fit the combined dataset.

The mean-shift and linear two-phase modeling approaches were further compared using AICc (Table 7). On the basis of this criterion, the mean-shift model was again selected as the best fit for eastern Maine and the two-phase model for western Maine and western plus eastern Maine. The difference in AICc between these two models is small, especially for western and eastern Maine combined, indicating that the two models essentially perform equally well.

Table 7.

AICc values calculated for the mean-shift and two-phase models for each dataset.

| Region | AICc for mean-shift model | AICc for two-phase model |

|---|---|---|

| Western Maine | 63.1 | 55.3 |

| Eastern Maine | 54.9 | 56.9 |

| Western + Eastern Maine | 93.0 | 92.7 |

4 Discussion

Interannual variability is a hallmark of many HAB events worldwide. Here we document toxin variability in Maine with 34 years of data from shellfish monitoring programs. An informative HAB Index has been formulated that collapses large amounts of shellfish toxicity data into a single measure proposed as indicative of annual severity. This Index and other observations document long-term (decadal) trends in toxicity in both sections of the Maine coastline. We know of no similar formulation that can incorporate large amounts of annual monitoring data at multiple stations into a single index that can reveal annual and interannual trends in toxicity. The Index represents a novel and practical tool for resource managers in many areas of the world subject to toxic HABs.

Three models for trend analysis were explored to define toxicity eras or regimes and their associated change points within the HAB Index time series. In all cases, the models delineate decade-level trends in toxicity, although the nature of the trends that are identified differ, as do their implications. The difference between these three model formulations is evident in Figure 7, but the statistical analysis suggests that none consistently gave a better fit than the others. Nevertheless, the commonalities among the fitted models can now guide efforts to identify physical and/or biological mechanisms underlying the patterns revealed by the HAB Index. As discussed below, we hypothesize that major changes in the abundance of A. fundyense cysts may be a primary factor underlying the decadal trends in shellfish toxicity.

4.1 The Maine HAB Index

In Maine, managers face the same problem as their counterparts worldwide – the need to synthesize data from a large number of sampling stations over many years into a format that facilitates comparative analysis. This would help to address common questions such as whether a particular year is markedly different from those in the past, whether shellfish toxicity is becoming more or less severe through time, whether there are trends that may be associated with pollution, climate change, or other environmental factors, or whether monitoring policies should be changed to reflect geographic differences or toxicity patterns.

One approach to this type of retrospective analysis is that of Thomas et al. (2010) who used multivariate techniques to cluster monitoring stations along the GOM coast into multiple station groups that behaved in a similar manner with respect to each of several metrics of toxicity. Each metric yielded a different set of stations that grouped together, and each set of station groups could then be analyzed against environmental parameters to look for causative factors for the toxicity trends. That study provides a great deal of insight and detail, but the analytical approach is complex and may be difficult to implement as a general management tool in other regions. In a similar study using the same dataset, Nair et al. (2013) also divided the coast into station clusters and looked for correlations with environmental and oceanographic parameters. Here we took a simpler approach and divided the Maine coastline into two subregions - eastern and western Maine. We then examined three measures of PSP toxicity over 34 years and combined them into a HAB Index (Fig. 6; Table 2) that provides a single measure of annual severity of toxicity.

Our separation of the coast of the GOM into two regions is based on established hydrographic features, including the offshore veering of the MCC near Penobscot Bay (e.g., Brooks, 1985; Lynch et al., 1997; Pettigrew et al., 2005), Alexandrium population distributions documented during the ECOHAB – GOM program (Townsend et al., 2001; Anderson et al., 2005d) as well as past patterns of shellfish toxicity in the region (e.g. Nair et al., 2013). In the latter context, it has long been known that Penobscot Bay (Fig. 1) marks a boundary between a region to the west that exhibits toxicity relatively early in the season compared to areas in eastern Maine and the BOF (Hurst and Yentsch, 1981; Shumway et al., 1988; Bean et al., 2005; Luerssen et al., 2005; Thomas et al., 2010). Both Thomas et al. (2010) and Nair et al. (2013) used statistical approaches to identify multiple station clusters in the GOM that group together and are generally in close geographic proximity. These workers conclude that many of the factors that drive toxicity patterns in the GOM are regional with a separation near Penobscot Bay, consistent with our western and eastern Maine subregions.

4.1.1 Individual Index metrics

Much can be learned from the individual metrics that comprise the HAB Index. For example, toxicity typically begins 2.5 weeks earlier in the west than in the east and ends approximately one month earlier (Figure 4, Table 3), such that toxicity duration is roughly the same. This is consistent with McGillicuddy et al.'s (2005a) conceptual model of Alexandrium bloom dynamics in the GOM in which warmer, early season temperatures in the west lead to higher growth rates than in the east, and an earlier onset of toxicity.

Another general observation is that in the 1990s and early 2000s era when toxicity and thus the HAB Index were low, bloom duration was short relative to other intervals (Figs. 4, 5). This reflects early bloom terminations more than later onsets, as the average termination date over the 1990s in western Maine was July 5th, compared to September 15th for the 1978-1989 interval (i.e., 60+ days later). The average dates of western Maine bloom onsets in the 1990s differed by only 11 days versus the 1978 – ‘89 interval. The shorter blooms that occurred during the low toxicity regime in the ‘90s thus started at nearly the same time of the year as the longer duration ones of earlier and later years, but terminated earlier. This is probably because bloom initiation is linked to cyst germination which is controlled by an internal clock in A. fundyense in the GOM (Anderson and Keafer, 1987; Matrai et al., 2005). Germination onset would thus be relatively invariant from year to year, leading to similar times for first detection of toxicity within a region. The differences in termination dates in these toxicity regimes or eras suggests that it may be possible to use the methods of Thomas et al. (2010) and Horecka et al. (this issue) to identify physical mechanisms that resulted in shortened bloom duration (i.e., led to earlier termination) during the 1990s or early 2000s, or conversely, lengthened them in the 1970s, 1980s, and mid to late 2000s. Alternatively, earlier bloom termination may have been caused by chemical and biological factors such as nutrient limitation and grazing of the Alexandrium population.

4.2 Trend analysis of the HAB Index

The composite HAB Indices for eastern and western Maine (Fig. 6) reveal significant variability in overall toxicity between individual years. Based on visual inspection of the data – two or three long-term, decadal patterns or regimes are evident in both subregions (Fig. 7). One view is that the HAB Index for western Maine shows a 13-year period from 1978 to 1990 that has high, mean toxicity (12 of 13 years at an Index ≥8), followed by a 14-year interval (1991-2004) of low toxicity (14 of 14 Index values between 3 and 7), and thereafter high values of toxicity from 2005 to the present (6 of 7 Index values ≥8). Similar trends are found in the eastern Maine HAB Index. Another view is that of a V-shaped pattern in which high toxicity in the late 1970s and early 1980s decreases steadily to a low in the mid 1990s, and then increases thereafter. Yet another view of the time series would be episodic pulses of high toxicity followed by a gradual decline.

These interpretations were explored in detail through trend analysis to determine whether the HAB Index time series best fitted a mean-shift model in which three eras of toxicity are observed (high →low → high toxicity), a two-phase linear model (decreasing → increasing toxicity), or a third, pulse-decline model (high → declining → high → declining toxicity). Based on the RSS, the mean-shift model was a better fit for eastern Maine, the two-phase model for western Maine, and the pulse-decline model for western plus eastern Maine combined, though the difference between the models is small (i.e., differed by < 20%). Any of the three models could thus be used to characterize the time-series.

The underlying mechanisms and implications of the three model formulations, however, are different. In the mean-shift model, major transitions from one toxicity era to another occur over relatively short intervals (Fig. 7A-C, Table 4). The rapid decline in toxicity followed by an interval of sustained, low levels is analogous perhaps to a disastrous year class of fish that affects harvest yield for many years thereafter. It may thus be informative to examine environmental data for the years around the time the mean shifts occurred, as this might identify important environmental conditions that can either dramatically reduce A. fundyense abundance and associated shellfish toxicity for an extended interval thereafter, or, conversely, initiate a new, higher toxicity era. The years that might be worth scrutinizing in this regard would be 1990-1993 on the downside, and 2002-2004 on the upside (Figs. 6, 7). The HAB Index makes identification of these critical time intervals relatively easy. Below we hypothesize that these transitions were linked to major changes in cyst abundance.

Conversely, with the two-phase model, the decline in toxicity from the late 1970s to the mid 1990s would be consistent with a gradual change in A. fundyense population size in nearshore waters, which could arise from a variety of factors (declining cyst abundance (see below), changing nutrient availability, other biological factors such as grazing), or it might reflect systematic changes in the physical factors that regulate the delivery of offshore blooms to shore. An analysis of the environmental factors that might correlate with this declining interval, or with the increasing toxicity era that followed would require the multivariate approach of Thomas et al. (2010), Nair et al. (2013), and Horecka et al. (this issue), and is beyond the scope of this study.

The pulse-decline model could be explained by a major pulse of cyst deposition and resulting high toxicity (McGillicuddy et al., 2011) that is followed by years in which that inventory gradually declines, with a corresponding decline in toxicity. In this instance, the first pulse probably occurred near 1972, the time of a major red tide and PSP outbreak in the region (Hurst, 1975; Mulligan, 1975). Based on the model analysis, the second pulse occurred in the 2002 – 2004 time frame. Since then, there are too few years to reveal a declining trend in western Maine, but a modest downward trend is evident for eastern Maine and the combined region. More detail on the blooms for both of these pulse intervals are given in Section 4.5 below.

Examining the years preceding the 34-year dataset, another era (with low or undetectable toxicity for at least 13 years from 1958 to 1971) can be postulated based on the general lack of toxicity in that portion of coastal Maine over that interval. In eastern Maine, that time was associated with geographically limited and infrequent toxicity. Specifically, Hurst (1975) points out that the Maine biotoxin monitoring program began in 1958 after a PSP outbreak in New Brunswick, Canada, but was focused only on eastern Maine. Closures due to PSP in eastern Maine occurred in only 5 years out of 14 between 1958 and 1970 (Shumway et al., 1988). Thereafter, testing was added in western portions of the state. In 1961, toxin was detected along the entire Maine coast (Hurst, 1975), but all stations in western Maine, except those at two offshore islands, had toxin levels below quarantine thresholds. Thereafter, there were no closures in western Maine until 1972, when a visible A. fundyense red tide occurred, affecting the entire Maine coast, as well as waters in New Hampshire and Massachusetts (Mulligan, 1975; Hartwell, 1975). The large scale of the 1972 outbreak led to an expanded monitoring program that includes 160 stations (Bean et al., 2005). Closures are now frequent in western Maine – occurring in over 80% of the 34 years studied here (Kleindinst et al., this issue). We believe it is important to review and document these early toxicity data in Maine, as they support the view that in the 20 years before the HAB Index calculations began, toxicity was low in both eastern and western Maine, marking another low toxicity era similar to the one observed in the 1990s.

4.3 Upstream and downstream patterns

Given the linkage between A. fundyense blooms in the BOF and those in eastern Maine (Aretxabaleta et al., 2008; 2009), and the linkages between blooms in western Maine and those in New Hampshire and Massachusetts Bay (Anderson, 1997), one wonders whether the patterns indicated by the Maine HAB Index are reflected in toxicity patterns in these upstream and downstream areas. Unfortunately, the data needed to calculate the HAB Index are not currently available for Massachusetts or the BOF, but other measures of toxicity can be examined in this context.

Toxicity in Massachusetts and southern New England waters is not initiated from localized cyst germination (A. fundyense cyst abundances are low in that region; Anderson et al., 2005c. this issue), but rather from the advection of established vegetative populations from western Maine via the MCC (Anderson, 1997; Stock et al., 2005; Stock et al., 2007). It therefore is not surprising that the PSP toxicity observed in Massachusetts Bay shows a pattern with relatively frequent and high toxicity in the 1970s, ‘80s, and early ‘90s, but no toxicity from 1994 through 2004 (data not shown). Thereafter, toxicity in this region has been frequent but variable in magnitude (McGillicuddy et al., 2011). These patterns are generally consistent with changes in the western Maine HAB Index (Fig. 7A,D,G).

In the upstream region, the situation is more complex, as the A. fundyense blooms are strongly influenced by a retentive gyre at the mouth of the BOF (Martin et al., this issue) and the extent to which cells in the BOF escape into the eastern GOM (Aretxabaleta et al., 2008; 2009). When the annual mean toxicity at multiple stations in the BOF was compared with the eastern Maine HAB Index, no significant correlation was observed. This lack of correlation may reflect the nature of interannual variability in the “leakiness” of the BOF, which Aretxabaleta et al. (2009) argue depends primarily on the strength of the BOF gyre, which is in turn influenced by stratification within the Grand Manan basin. Many other factors modulate the leakiness on a variety of time scales (Aretxabaleta et al., 2008), including the residual tidal circulation, frontal retention during stratified periods, wind stress, and interactions with the adjacent circulation of the GOM. These forcings would all modulate the delivery of cells into eastern Maine, and may thereby influence interannual variability in toxicity in downstream areas.

4.4 Underlying mechanisms

Although the dataset examined in the Thomas et al. (2010) study was shorter than the 34 years (1978 – 2011) that we utilized, these authors described what was, in effect, a mean-shift pattern in toxicity. That study tried to correlate toxicity patterns with interannual environmental variables (e.g., temperature, river discharge, salinity, wind stress), but only western Maine stations showed correlations with any tested environmental metric. There, positive correlations were observed between toxicity and early season wind stress driving onshore Ekman transport; negative correlations were found with wind stress driving offshore transport, and with summer cross-shelf surface temperature gradients. Similar conclusions were drawn from the analysis of the same dataset by Nair et al. (2013). The correlations between toxicity and wind direction stems from the tendency of downwelling-favorable winds to bring toxic Alexandrium cells to shore, and upwelling-favorable winds to move them offshore and away from shellfish have been noted in multiple other studies (e.g., Franks and Anderson 1992a,b; McGillicuddy et al., 2003; Anderson et al., 2005a). Such relationships have also been noted for the western Irish coast by Raine et al. (2010).

Thomas et al. (2010) reported a temporal autocorrelation in their data, suggesting that processes with time scales longer than a year are important in controlling toxicity in the GOM. Our study suggests that this factor may be cyst abundance. This hypothesis is based on the significant and positive relationship we have documented between fall A. fundyense cyst abundance and bloom magnitude the following year (McGillicuddy et al., 2011; Anderson et al., this issue). Although our cyst survey data do not span the same interval as the 34 years of toxicity records, it is nevertheless possible to compare cyst abundance and the HAB Index for the years that are in common to determine if a relationship exists between the two. The first large–scale cyst survey for the GOM conducted in 1997 (Anderson et al., 2005c) yielded very low cyst abundance compared to eight subsequent surveys from 2004 - 2011 (Anderson et al., this issue). When scaled to represent a common cyst-sampling domain among years, the 1997 cyst abundance was 1/11th of what it was in 2009, for example. This low abundance occurred within the decade when the HAB Index indicates there was low-level toxicity in both the eastern and western subregions (Fig. 6). The significantly higher cyst abundances recorded from 2004 – 2011 (Anderson et al., this issue) coincide with the era of renewed high toxicity.

Unfortunately, very limited quantitative cyst data are available in the GOM prior to the 1997 survey, although two surveys provide insights. Anderson and Keafer (1985) measured A. fundyense cyst abundances in the WGOM in 1983 and 1984. The northernmost stations of that sampling effort (Massachusetts Bay to Portsmouth, NH) were located in the same general area as the westernmost stations sampled during the 1997 large-scale survey. Counts from 1983 and 1984 were markedly (>10X) higher than those at similar locations in that 1997 survey. For example, the mean cyst concentrations from 6 stations offshore of Portsmouth, New Hampshire were 664 cysts cm−3 in 1983 (0-2 cm) and 711 cysts cm−3 in 1984 (0-2 cm) vs. < 50 cysts cm−3 observed in the 0-1 cm layer from that same area during the large-scale survey in 1997. Furthermore, when the 0-1 cm layer was repeatedly sampled at a single station in that area (station 29; latitude 43.00N longitude 70.31W) over a 4-year period that spanned 1984 to 1987, the A. fundyense cyst counts ranged from a minimum of 318 cysts cm−3 to a maximum of 992 cysts cm−3 with a mean of 584 cysts cm−3 observed (n=14), more than a order of magnitude higher than any cyst concentration observed near Station 29 in 1997.

Although these 1983, 1984 data are obviously limited in scale, we note that an ongoing statistical analysis of A. fundyense cyst abundance patterns from nine years of large-scale surveys in the GOM demonstrates that there is a generic cyst distribution pattern in the region, with cyst abundance at individual stations varying in a consistent pattern from year to year relative to the surrounding stations (A. Solow, unpub. data). If that same spatial pattern were present during the time of the high relative cyst abundance measurements in 1983 and 1984, which seems likely, those values would be representative of the broader regional cyst distribution.

We thus hypothesize that the decade-level trends in regional toxicity evident in the HAB Index (Figs. 6, 7) correspond to major differences in cyst abundance over that same interval. The data in support of this hypothesis are limited, but can be further tested in the future.

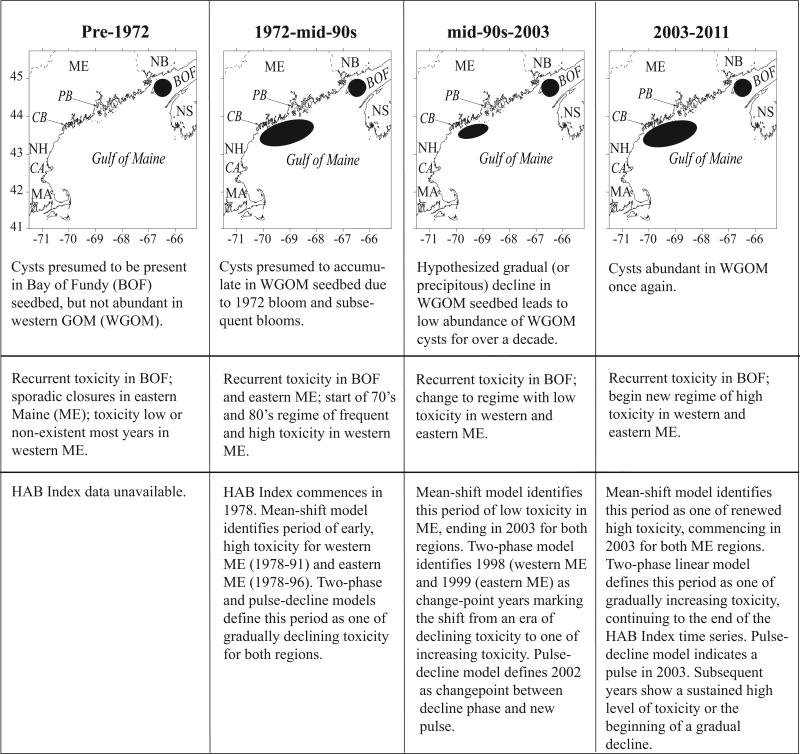

4.5 Conceptual model of historical toxicity patterns

Figure 8 provides a conceptual model of the historical toxicity patterns and their relationship with both measured and hypothesized cyst abundance and distribution in the region. We acknowledge that portions of this model are speculative, as they depend on either postulated cyst abundance before the times of major cyst surveys, or limited cyst survey data, as for 1983 and 1984. Nevertheless, we feel it is worthwhile to advance a long-term conceptual model that updates our view of the bloom and toxin dynamics of this GOM system, and that can guide future studies.

Figure 8.

Conceptual model of historical toxicity patterns and their relationship with measured and hypothesized cyst abundance and distribution in the Gulf of Maine region. The shapes used for the cyst seedbeds are not intended to be accurate but only represent general features. Note that the size of the cyst beds in the first two panels is based on inference rather than direct measurement because large-scale cyst surveys were not conducted in those years. Nevertheless, the distribution depicted is inferred from toxicity data and other observations.

We argue that the first toxicity era or regime is the “pre-1972” interval in which toxicity was high and recurrent in the BOF (as it has been for hundreds of years (Medcof et al., 1947; Needler, 1949; Prakash et al., 1971)), sporadic and infrequent in eastern Maine, and essentially non-existent in western Maine, New Hampshire, or Massachusetts (Hurst, 1975; Shumway et al., 1988). No cyst surveys were conducted in that interval (in fact the cyst of A. fundyense had not yet been discovered; Dale, 1977; Anderson and Wall, 1978), but we hypothesize that the BOF cyst seedbed was much as it is today, and that the mid-coast Maine seedbed was sparse or nonexistent. This supposition can perhaps be tested someday using the fossil cyst record.

The contrast in toxicity between the years before and after the 1972 GOM red tide is remarkable. With no closures in the west, and only sporadic closures in the east prior to that year (Hurst, 1975; Shumway et al., 1988), A. fundyense blooms have since become an annual phenomenon along the entire coast, including western Maine. Several studies indicate that the 1972 event deposited A. fundyense cysts in high abundance in the western gulf region, creating what we now refer to as the mid-coast Maine seedbed, which was sustained through time with the recurrent A. fundyense blooms of the 1970s and ‘80s (e.g., Mulligan, 1975; Anderson, 1997). The only quantitative cyst abundance surveys during that interval were from the 1983 and 1984 small-scale surveys in the WGOM (Anderson and Keafer, 1985), which documented high A. fundyense cyst abundances. The corresponding toxicity pattern for that era was one of continued PSP outbreaks in the BOF, and frequent and high toxicity events in eastern and western Maine, as well as in downstream New Hampshire and Massachusetts. Subsequently, we theorize that there was either a gradual decline in cyst abundance over a decade or more during this interval (the two-phase and pulse-decline models), or a precipitous drop (mean-shift model) occurring around 1990. We believe this low toxicity and low cyst abundance interval persisted until the early 2000s, consistent with the low cyst concentrations in the 1997 large-scale cyst survey (Anderson et al., 2005c).

For reasons that are not well understood (Anderson et al., this issue), cyst abundance increased greatly between the 1997 and the 2004 surveys. This may relate to unusually high A. fundyense cell concentrations observed in both the BOF and the EGOM in the fall of 2003. In the BOF, cell densities were the highest observed in more than two decades at Wolves Island (Martin et al., this issue). Also, high cyst abundance in 2004 was the main explanation for a major regional A. fundyense bloom in 2005 (He et al., 2008), extending from eastern Maine to southern Massachusetts and its offshore islands (Anderson et al., 2005b). Those high levels of cyst abundance have persisted to this writing, fluctuating 2-5-fold among years, but never falling to the low level reported in 1997 (Anderson et al., this issue). Toxicity has generally been high but variable, as documented in the western and eastern Maine HAB Indices (Figs. 6, 7). The new regime of high toxicity that began in 2002 - 2004 may be similar to that experienced after the 1972 red tide, which was followed by 17 years of frequent and high toxicity events (Fig. 6), possibly in a gradually decreasing trend. If history is giving us a view of the future, the GOM may have entered a new regime of high cyst abundance and high or gradually declining shellfish toxicity that could last for a decade or more.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to John Hurst, who established and ran the Maine Biotoxin monitoring program for over 40 years. His insights and wisdom on the regional A. fundyense blooms are legendary, built on years of keen observations and inquiry. We can only hope that the concepts presented here meet with his approval, though he undoubtedly would repeat a phrase we heard often: “It sure takes you scientists a long time to answer a simple question.” We gratefully acknowledge the thoughtful comments of several anonymous reviewers who greatly improved this manuscript.

Research support provided through the Woods Hole Center for Oceans and Human Health, National Science Foundation (NSF) Grants OCE- 1128041 and OCE-1314642; and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Grant 1-P50-ES021923-01, the ECOHAB Grant program through NOAA Grants NA06NOS4780245 and NA09NOS4780193, the MERHAB Grant program through NOAA Grant NA11NOS4780025, the PCMHAB Grant program through NOAA Grant NA11NOS4780023, and funding through the states of ME, NH, and MA. Funding for J.L. Martin was provided by Fisheries and Oceans Canada. This is ECOHAB contribution #735; MERHAB contribution #168; PCMHAB contribution #7.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

In this study, we have focused on the harmful algal species Alexandrium tamarense Group I, which we refer to as A. fundyense, the renaming proposed by Lilly et al. (2007).

References

- Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Contr. 1974;19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Salgado XAA, Figueiras FG, Pérez FF, Groom S, Nogueira E, Borges AV, Chou L, Castro CG, Moncoiffé G, Ríos AF, Miller AEJ, Frankignoulle M, Savidge G, Wollast R. The Portugal coastal counter current off NW Spain: new insights on its biogeochemical variability. Prog. in Oceanogr. 2003;56:281–321. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DM. Bloom dynamics of toxic Alexandrium species in the northeastern United States. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1997;42:1009–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DM. Physiology and bloom dynamics of toxic Alexandrium species, with emphasis on life cycle transitions. In: Anderson DM, Cembella AD, Hallegraeff GM, editors. The Physiological Ecology of Harmful Algal Blooms. Springer-Verlag; Heidelberg: 1998. pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DM, Keafer BA. An endogenous annual clock in the toxic marine dinoflagellate Gonyaulax tamarensis. Nature. 1987;325:616–617. doi: 10.1038/325616a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DM, Keafer BA. Dinoflagellate cyst dynamics in coastal and estuarine waters. In: Anderson DM, White AW, D. G. Baden DG, editors. Toxic Dinoflagellates. Proceedings of the Third International Conference. Elsevier; New York: 1985. pp. 219–224. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DM, Keafer BA, Geyer WR, Signell RP, Loder TC. Toxic Alexandrium blooms in the western Gulf of Maine: the plume advection hypothesis revisited. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2005a;50(1):328–345. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DM, Keafer BA, Kleindinst JL, McGillicuddy DJ, Jr., Martin JL, Norton K, Pilskaln CH, Smith JL. Alexandrium fundyense cysts in the Gulf of Maine: time series of abundance and distribution, and linkages to past and future blooms. Deep-Sea Res. II. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.10.002. in this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DM, Keafer BA, McGillicuddy DJ, Mickelson MJ, Keay KE, Libby PS, Manning JP, Mayo CA, Whittaker DK, Hickey JM, He R, Lynch DR, Smith KW. Initial observations of the 2005 Alexandrium fundyense bloom in southern New England: General patterns and mechanisms. Deep-Sea Res. II. 2005b;52(19-21):2856–2876. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DM, Stock CA, Keafer BA, Bronzino Nelson A, Thompson B, McGillicuddy DJ, Keller M, Matrai PA, Martin J. Alexandrium fundyense cyst dynamics in the Gulf of Maine. Deep-Sea Res. II. 2005c;52(19-21):2522–2542. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DM, Townsend DW, McGillicuddy DJ, Turner JT. The Ecology and Oceanography of Toxic Alexandrium fundyense Blooms in the Gulf of Maine. Deep-Sea Res. II. 2005d;52(19-21):2365–2876. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DM, Wall D. Potential importance of benthic cysts of Gonyaulax tamarensis and G. excavata in initiating toxic dinoflagellate blooms. J. Phycol. 1978;14:224–234. [Google Scholar]

- Aretxabaleta AL, McGillicuddy DJ, Smith KW, Lynch DR. Model simulations of the Bay of Fundy gyre: 1. Climatological results. J. Geophys. Res. 2008;113:C10027. doi: 10.1029/2007JC004480. doi:10.1029/2007JC004480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aretxabaleta AL, McGillicuddy DJ, Smith KW, Manning JP, Lynch DR. Model simulations of the Bay of Fundy gyre: 2. Hindcasts for 2005-2007 reveal interannual variability in retentiveness. J. Geophys. Res. 2009;114:C09005. doi: 10.1029/2008JC004948. doi:10.1029/2008JC004948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists . Standard Mouse Bioassay for Paralytic Shellfish Toxins. In: Horwitz W, editor. Official Methods of Analysis. 13th ed. Association of Official Analytic Chemists; Washington, D.C. USA: 1980. pp. 298–299. [Google Scholar]

- Azanza RV, Taylor FJRM. Are Pyrodinium blooms in the Southeast Asian region recurring and spreading? Aview at the end of the millenium. Ambio. 2001;30:356–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean LL, McGowan JD, Hurst JW., Jr. Annual variations in paralytic shellfish poisoning in Maine, USA, 1997-2001. Deep-Sea Res. II. 2005;19-21:2834–2842. [Google Scholar]

- Bricelj VM, Shumway SE. Paralytic shellfish toxins in bivalve molluscs: occurrence, transfer kinetics and biotransformation. Rev. Fisher. Sci. 1998;6(4):315–383. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DA. Vernal circulation in the Gulf of Maine. J. Geophys. Res. 1985;90:4687–4705. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model Selection and Multi-model Inference. Springer; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Butman B, Aretxabaleta AL, Dickhudt PJ, Dalyander PS, Sherwood CR, Anderson DM, Keafer BA, Signell RP. Investigating the importance of sediment resuspension in Alexandrium fundyense cyst population dynamics in the Gulf of Maine. Deep-Sea Res. II. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.10.011. in this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale B. Cysts of the toxic red-tide dinoflagellate Gonyaulax excavata Balech from Oslofjorden, Norway. Sarsia. 1977;63:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson G, Nishitani L. The possible relationship of El Niño/Southern Oscillation events to interannual variations in Gonyaulax populations as shown by records of shellfish toxicity. In: Wooster WS, Fluharty DL, editors. Proceedings of the meeting on El Niño effects in the Eastern Subarctic Pacific, Washington Sea Grant Program. University of Washington; 1985. pp. 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- Franks PJS, Anderson DM. Alongshore transport of a toxic phytoplankton bloom in a buoyancy current – Alexandrium tamarense in the Gulf of Maine. Mar. Biol. 1992a;112(1):153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Franks PJS, Anderson DM. Toxic phytoplankton blooms in the southwestern Gulf of Maine – testing hypotheses of physical control using historical data. Mar. Biol. 1992b;112(1):165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell AD. Hydrographic factors affecting the distribution and movement of toxic dinoflagellates in the western Gulf of Maine. In: LoCicero VR, editor. Toxic Dinoflagellate Blooms. Proceedings of the International Conference (lst) Massachusetts Science and Technology Foundation. Wakefield, MA: 1975. pp. 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- He R, McGillicuddy DJ, Keafer BA, Anderson DM. Historic 2005 toxic bloom of Alexandrium fundyense in the western Gulf of Maine: 2. Coupled Biophysical Numerical Modeling. Journal of Geophysical Research-Oceans. 2008;113:C07040. doi: 10.1029/2007JC004602. doi:10.1029/2007JC004602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horecka HM, Thomas AC, Weatherbee RA. Environmental links to interannual variability in shellfish toxicity in Cobscook Bay and eastern Maine, a strongly tidally mixed region. Deep-Sea Res. II. in this issue http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.01.013.

- Hurst JW., Jr. History of paralytic shellfish poisoning on the Maine coast.. In: LoCicero VR, editor. Toxic Dinoflagellate Blooms; Proceedings of the International Conference (lst) Massachusetts Science and Technology Foundation.1975. pp. 525–528. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst JW, Yentsch CM. Patterns of intoxication of shellfish in the Gulf of Maine coastal waters. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Science. 1981;38:152–156. [Google Scholar]

- Keafer BA, Churchill JH, McGillicuddy DJ, Jr., Anderson DM. Bloom development and transport of toxic Alexandrium fundyense populations within a coastal plume in the Gulf of Maine. Deep-Sea Res. II. 2005;52(19-21):2674–2697. [Google Scholar]

- Kirn SL, Townsend DW, Pettigrew NR. Suspended Alexandrium spp. hypnozygotes cysts in the Gulf of Maine. Deep-Sea Res. II. 2005;52(19-21):2543–2559. [Google Scholar]

- Kleindinst JL, Anderson DM, McGillicuddy DJ, Jr., Stumpf RP, Fisher KM, Darcie Couture D, Hickey JM, Nash C. Categorizing the severity of paralytic shellfish poisoning outbreaks in the Gulf of Maine for forecasting and management. Deep-Sea Res. II. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.03.027. in this issue http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lilly EL, Halaynch KM, Anderson DM. Species boundaries and global biogeography of the Alexandrium tamarense complex (Dinophyceae). J. Phycol. 2007;43:1329–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Luerssen RM, Thomas AC, Hurst J. Relationships between satellite-measured thermal features and Alexandrium-imposed toxicity in the Gulf of Maine. Deep-Sea Res. II. 2005;52(19-21):2656–2673. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch DR, Holboke MJ, Naimie CE. The Maine coastal current: spring climatological circulation. Cont. Shelf Res. 1997;17:605–634. [Google Scholar]

- Maclean JL. Hallegraeff GM, Maclean JL, editors. An overview of Pyrodinium red tides in the Western Pacific. Biology, Epidemiology and Management of Pyrodinium Red Tides. ICLARM Conference Proceedings. 1989:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JL, LeGresley MM, Hanke A. Alexandrium fundyense population dynamics in the Bay of Fundy - resting cysts and summer blooms since. 1980 in this issue. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JL, Richard D. Shellfish toxicity from the Bay of Fundy, eastern Canada, 50 years in retrospect.. In: Yasumoto T, Oshima Y, Fukuyo Y, editors. Harmful and Toxic Algal blooms; Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Toxic Phytoplankton; Sendai, Japan. 12-16, 1995; Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO; 1996. pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Matrai P, Thompson B, Keller M. Circannual excystment of resting cysts of Alexandrium spp. from eastern Gulf of Maine populations. Deep-Sea Res. II. 2005;52:2560–2568. [Google Scholar]

- McGillicuddy DJ, Jr., Anderson DM, Lynch DR, Townsend DW. Mechanisms regulating large-scale seasonal fluctuations in Alexandrium fundyense populations in the Gulf of Maine: Results from a physical-biological model. Deep-Sea Res. II. 2005a;52(19-21):2698–2714. [Google Scholar]

- McGillicuddy DJ, Jr., Anderson DM, Solow AR, Townsend DW. Interannual variability of Alexandrium fundyense abundance and shellfish toxicity in the Gulf of Maine. Deep-Sea Res. II. 2005b;52(19-21):2843–2855. [Google Scholar]

- McGillicuddy DJ, Signell RP, Stock CA, Keafer BA, Keller MD, Hetland RD, Anderson DM. A mechanism for offshore initiation of harmful algal blooms in the coastal Gulf of Maine. J. Plankt. Res. 2003;25(9):1131–1138. [Google Scholar]

- McGillicuddy DJ, Jr., Townsend DW, He R, Keafer BA, Kleindinst JL, Li Y, Manning JP, Mountain DG, Thomas MA, Anderson DM. Suppression of the 2010 Alexandrium fundyense bloom by changes in physical, biological, and chemical properties of the Gulf of Maine. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2011;56(6):2411–2426. doi: 10.4319/lo.2011.56.6.2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medcof JC, Leim AH, Needler AB, Gibbard J, Naubert J. Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning on the Canadian Atlantic Coast. Bulletin of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. 1947;LXXV:32. [Google Scholar]

- Moore SK, Mantua NJ, Kellogg JP, Newton JA. Local and large-scale climate forcing of Puget Sound oceanographic properties on seasonal to interdecadal timescales. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2008;53:1746–1758. [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan HF. Oceanographic factors associated with New England red-tide blooms.. In: LoCicero VR, editor. Toxic Dinoflagellate Blooms; Proceedings of the International Conference (lst) Massachusetts Science and Technology Foundation.1975. pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nair A, Thomas AC, Borsuk ME. Interannual variability in the timing of New England shellfish toxicity and relationships to environmental forcing. Sci. Total Environ. 2013;447:255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needler AB. Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning and Gonyaulax tamarensis. J. Fish. Res. Board of Canada. 1949;7:490–504. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew NR, Churchill JH, Janzen CD, Mangum LJ, Signell RP, Thomas AC, Townsend DW, Wallinga JP, Xue H. The kinematic and hydrographic structure of the Gulf of Maine Coastal Current. Deep-Sea Res. II. 2005;52(19-21):2369–2391. [Google Scholar]

- Pilskaln CH, Hayashi K, Keafer BA, Anderson DM, McGillicuddy DJ. Benthic nepheloid layers in the Gulf of Maine and Alexandrium cyst inventories. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.05.021. in this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash A, Medcof JC, Tenant AD. Paralytic shellfish poisoning in eastern Canada. Fisheries Research Board of Canada, Bulletin; 1971. p. 177. [Google Scholar]

- Raine R, McDermott G, Silke J, Lyons K, Nolan G, Cusack C. A simple short range model for the prediction of harmful algal events in the bays of southwestern Ireland. J. Mar. Sys. 2010;83:150–157. [Google Scholar]

- Shumway SE, Sherman-Caswell S, Hurst JW. Paralytic shellfish poisoning in Maine: Monitoring a monster. J. Shellfish Res. 1988;7:643–652. [Google Scholar]

- Stock CA, McGillicuddy DJ, Solow AR, Anderson DM. Evaluating hypotheses for the initiation and development of Alexandrium fundyense blooms in the western Gulf of Maine using a coupled physical-biological model. Deep-Sea Res. II. 2005;52(19-21):2715–2744. [Google Scholar]

- Stock CA, McGillicuddy DJ, Anderson DM, Solow AR, R.P. Signell RP. Blooms of the toxic dinoflagellate Alexandrium fundyense in the western Gulf of Maine in 1993 and 1994: A comparative modeling study. Cont. Shelf Res. 27:2486–2512. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AC, Weatherbee R, Xue H, Liu G. Interannual variability of shellfish toxicity in the Gulf of Maine: Time and space patterns and links to environmental variability. Harmful Algae. 2010;9:458–480. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend DW, Pettigrew NR, Thomas AC. Offshore blooms of the red tide dinoflagellate, Alexandrium sp., in the Gulf of Maine. Cont. Shelf Res. 2001;21:347–369. [Google Scholar]

- Trainer VL, Eberhart B-TL, Wekell JC, Adams NA, Hanson L, Cox F, Dowell J. Paralytic shellfish toxins in Puget Sound, Washington State. J. Shellfish Res. 2003;22(1):213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Usup G, Azanza R. Physiology and bloom dynamics of the tropical dinoflagellate Pyrodinium bahamense. In: Anderson DM, Cembella AD, Hallegraeff GM, editors. The Physiological Ecology of Harmful Algal Blooms. Springer-Verlag; Heidelberg: 1998. pp. 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- White AW. Relationships of environmental factors to toxic dinoflagellate blooms in the Bay of Fundy. Rapports et Proces-verbaux des Réunions. Conseil International pour l'Éxploration de la Mer. 1987;187:38–46. [Google Scholar]

- White AW, Lewis CM. Resting cysts of the toxic, red tide dinoflagellate Gonyaulax excavata in Bay of Fundy sediments. Can. J. Aquatic Sci. 1982;39(8):1185–1194. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.