Abstract

Haems are metalloporphyrins that serve as prosthetic groups for various biological processes including respiration, gas sensing, xenobiotic detoxification, cell differentiation, circadian clock control, metabolic reprogramming and microRNA processing1–4. With a few exceptions, haem is synthesized by a multistep biosynthetic pathway comprising defined intermediates that are highly conserved throughout evolution5. Despite our extensive knowledge of haem biosynthesis and degradation, the cellular pathways and molecules that mediate intracellular haem trafficking are unknown. The experimental setback in identifying haem trafficking pathways has been the inability to dissociate the highly regulated cellular synthesis and degradation of haem from intracellular trafficking events6. Caenorhabditis elegans and related helminths are natural haem auxotrophs that acquire environmental haem for incorporation into haemoproteins, which have vertebrate orthologues7. Here we show, by exploiting this auxotrophy to identify HRG-1 proteins in C. elegans, that these proteins are essential for haem homeostasis and normal development in worms and vertebrates. Depletion of hrg-1, or its paralogue hrg-4, in worms results in the disruption of organismal haem sensing and an abnormal response to haem analogues. HRG-1 and HRG-4 are previously unknown transmembrane proteins, which reside in distinct intracellular compartments. Transient knockdown of hrg-1 in zebrafish leads to hydrocephalus, yolk tube malformations and, most strikingly, profound defects in erythropoiesis—phenotypes that are fully rescued by worm HRG-1. Human and worm proteins localize together, and bind and transport haem, thus establishing an evolutionarily conserved function for HRG-1. These findings reveal conserved pathways for cellular haem trafficking in animals that define the model for eukaryotic haem transport. Thus, uncovering the mechanisms of haem transport in C. elegans may provide insights into human disorders of haem metabolism and reveal new drug targets for developing anthelminthics to combat worm infestations.

In animals, the terminal enzyme in haem synthesis, ferrochelatase, is located on the matrix side of the inner mitochondrial membrane8. Most newly synthesized haem must be transported through mitochondrial membranes to haemoproteins found in distinct intracellular membrane compartments6. Haem synthesis is regulated at multiple steps by effectors including iron, haem and oxygen to prevent the uncoordinated accumulation of haem or its precursors5. C. elegans is a haem auxotroph and is therefore a unique genetic animal model in which to identify the molecules and delineate the cellular pathways for eukaryotic haem transport6. Haem analogue studies have suggested that a haem uptake system exists in C. elegans7. Synchronized C. elegans cultures grown in axenic mCeHR-2 liquid medium9 and supplemented with haemin chloride revealed a robust uptake of fluorescent zinc mesoporphyrin IX (ZnMP) at a haem concentration of 20 µM or less, in contrast with worms grown at 100 µM haem or more (Fig 1a, b), suggesting that the transport and accumulation of haem are regulated.

Figure 1. Identification of hrg-1 and hrg-4 in C. elegans.

a, Fluorescent ZnMP (40 µM for 3 h) accumulation in worms grown in mCeHR-2 medium supplemented with 1.5 µM (left) and 500 µM (right) haem. Differential interference contrast (DIC, top) and rhodamine fluorescence (bottom). b, Total mean fluorescence intensity (filled circles) of ZnMP accumulated in worms (40 µM for 3 h) after 9 days of growth in mCeHR-2 medium supplemented with the indicated haem concentrations. Open diamonds, growth of worms in haemin. Results are means ± s.d. (n = 100). c, Northern blot analysis of hrg-1 and hrg-4 expression in response to 4 and 20 µM haem in mCeHR-2 medium. The blot was stripped and reprobed with gpd-2 as loading control. kb, kilobases. d, Expression of hrg-4 (circles) and hrg-1 (squares) mRNA estimated by quantitative RT–PCR from total RNA obtained from worms grown at the indicated haem concentrations. Each data point shows mean ± s.d. and the results are representative of three separate experiments. Inset: mRNA levels at higher haem concentrations. e, Multiple sequence alignment of C. elegans HRG-1 with its vertebrate orthologues. Asterisk, histidine (H90); circles, aromatic amino acids; box, putative transmembrane domains; YXXxφ, C-terminal tyrosine motif; D/EXXxLL, di-leucine motif. f, Phylogenetic analysis of HRG-1 proteins by using the neighbour-joining method. g, Predicted topology of C. elegans HRG-1 showing H90 in TMD2, and FARKY, the putative haem-interacting motif, in the cytoplasmic tail.

We conducted genome-wide microarrays to identify genes that are transcriptionally regulated by haem. Wild-type N2 worms were grown for two synchronized generations in 4 µM (low), 20 µM (optimal) and 500 µM (high) haem concentrations in liquid medium and their messenger RNA was hybridized to Affymetrix C. elegans genome arrays. Statistical analyses identified changes in 370 genes, of which about 164 had some sequence identity to genes in the human genome databases at the amino-acid level, and more than 90% of the genes had no functional annotation in the C. elegans database (Supplementary Table 1).

We postulated that the expression of genes that encode for haem transporters might be elevated during haem deficiency to maximize uptake of dietary haem. To identify candidate haem transporter genes, we sorted the 117 genes to identify those that were specifically upregulated in low haem (Supplementary Table 1, categories 1 and 2) and encoded for proteins with predicted transmembrane domains, transport functions, and/or haem/metalbinding motifs. F36H1.5 was > 10 fold upregulated at low haem but was undetectable at 500 µM haem, and the predicted open reading frame of 169 amino acids (≈19 kDa) showed similarities to high-affinity permease transporters10. We refer to F36H1.5 as haem responsive gene-4 (hrg-4). RNA blotting and qRT–PCR analysis revealed that hrg-4 mRNA was significantly upregulated (> 40 fold) at 4 µM haem but undetectable at 20 and 500 µM haem (Fig. 1c, d). We identified three putative paralogues of hrg-4 in the C. elegans genome; we termed them hrg-1 (R02E12.6), hrg-5 (F36H1.9) and hrg-6 (F36H1.10), with 27%, 39% and 35% overall amino-acid sequence identity, respectively (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 1a). Although both hrg-1 and hrg-4 were highly responsive to haem deficiency (Fig. 1c), the magnitude of change in mRNA expression at 1.5 µM haem and their responsiveness to haem-mediated repression were markedly different (Fig. 1d and inset). By contrast, hrg-5 and hrg-6 expression seemed to be constitutive and not regulated by haem (not shown). hrg-4, hrg-5 and hrg-6 are nematode-specific genes, whereas hrg-1 has orthologues with about 25% amino acid identity in vertebrates (Fig. 1e, f, and Supplementary Fig. 1). Topology modelling and motif analysis of HRG-1 identified four predicted transmembrane domains (TMDs) and a conserved tyrosine and acidic-dileucine-based sorting signal in the cytoplasmic carboxy terminus (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 1a)11. In addition, residues that could potentially either directly bind haem (H90 in TMD2) or interact with the haem side chains (FARKY) were situated in the C-terminal tail (Fig. 1e, g)12–14.

To study the function of hrg-1 genes in haem homeostasis, we generated a hrg-1::gfp transcriptional fusion in C. elegans. hrg-1::gfp was expressed specifically in the intestinal cells in larvae and adults (Fig. 2a). Its expression was regulated by feeding transgenic worms sequentially with Escherichia coli that had been grown on agar plates with or without exogenous haem (Fig. 2a). hrg-1 repression was specific to haem because neither protoporphyrin IX nor iron altered the expression of hrg-1::gfp (Fig. 2b). We next assessed the effect of HRG-1 and HRG-4 depletion in worms by RNA-mediated interference with three independent assays: first, the expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the hrg- 1::gfp haem sensor strain to monitor haem homeostasis; second, the accumulation of fluorescent ZnMP as a function of haem uptake; and third, animal viability in the presence of a cytotoxic haem analogue, gallium protoporphyrin IX (GaPP)7. Knockdown of hrg-4 by RNAi resulted in the expression of hrg-1::gfp, even though haem levels sufficient to suppress GFP were present in the diet (Fig. 2c). hrg-4 RNAi resulted in no detectable accumulation of ZnMP fluorescence in worms that were grown in 1.5 µM haem, a concentration that is sufficient to induce a robust uptake of haem (Fig. 2d). Consistent with these findings was our observation that progeny from hrg-4 RNAi worms were also markedly resistant to GaPP toxicity (Fig. 2e), in concordance with recent genome-wide studies revealing hrg-4 expression in the worm intestine15. In contrast, hrg-1 RNAi showed a significant derepression of GFP only at low haem levels in the hrg-1::gfp haem sensor strain (Fig. 2c), but no discernible effect on animal viability assessed with GaPP toxicity assays (Fig. 2e). We found that the intensity of ZnMP fluorescence was significantly greater in the intestines of HRG-1- depleted worms than in controls (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 2). The observed differences in RNAi phenotypes of hrg-4 and hrg-1 suggest that haem uptake into worm intestinal cells involves HRG-4, whereas HRG-1 mediates haem homeostasis by means of an intracellular compartment.

Figure 2. hrg-1 and hrg-4 are essential for haem homeostasis in C. elegans.

a, IQ6011 hrg-1::gfp ‘heme sensor’ strain responds to exogenous haem after sequential exposure to E. coli grown on agar plates in the absence (left and right) and presence (middle) of 200 µM haem. UTR, untranslated region. b, Spectrofluorometric measurements of GFP in worm lysates from IQ6011 strain grown in the presence of indicated concentrations of haem plus 20 µM PPIX or 1 mM FeCl3. Each data point shows mean ± s.d. and the results are representative of three separate experiments. c–e, Depletion of hrg-1 or hrg-4 in worms by RNAi with feeding bacteria. c, Dysregulation of GFP (means ± s.e.m.; n = 35–45 worms per treatment) in IQ6011 when fed with bacteria grown in the presence of 0, 5 and 25 µM haem. Values with different letter labels are significantly different (P < 0.001) within each treatment. d, Aberrant ZnMP fluorescence accumulation in worms fed with 10 µM ZnMP for 16 h. Scale bar, 50 µm. e, Differences in viable progeny (mean ± s.d.; n = 30 P0 worms per treatment) after 5 days of exposure to 1 µM GaPP plus RNAi bacteria. Filled bars, viable eggs; open bars, larvae. The results for c–e are representative of at least four separate experiments.

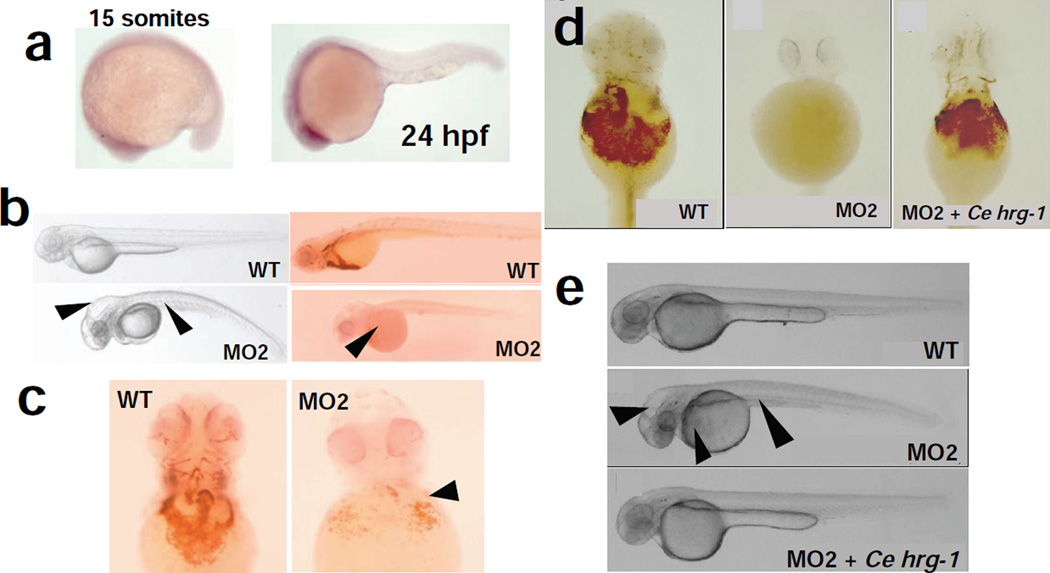

To dissect HRG-1 function in a vertebrate genetic model, we used zebrafish (Danio rerio). We reasoned that any perturbation in haem homeostasis would be manifested as haematological defects in the fish embryo16. BLAST searches revealed an orthologous gene on zebrafish chromosome 6 that shared about 21% amino acid identity with C. elegans HRG- 1. Whole-mount in situ hybridization of zebrafish embryos at the 15-somite stage and 24 h after fertilization showed zebrafish hrg-1 mRNA expressed throughout the embryo, including the central nervous system (Fig. 3a). To knock down hrg-1 in zebrafish, antisense morpholinos (MO2) were designed at the splice junctions to selectively induce hrg-1 mRNA mis-splicing and degradation. Embryos injected with MO2 had severe anaemia and lacked any detectable o-dianisidine-positive erythroid cells (Fig. 3b, c). MO2 morphants showed other developmental defects, including hydrocephalus and a curved body with shortened yolk tube.

Figure 3. HRG-1 is essential for erythropoiesis and development in zebrafish.

a, Zebrafish hrg-1 expression by whole-mount in situ hybridization: left, 15 somites; right, 24 h after fertilization. b, Knockdown of zebrafish hrg-1 by using morpholinos (MO2) against zebrafish hrg-1 reveals severe anaemia with very few o-dianisidine-positive red cells (arrows, right panel), hydrocephalus, and a curved body with shortened yolk tube (arrows, left panel). WT, wild type. c, Decrease in haemoglobinized cells in MO2 morphants (arrows). d, e, Cehrg-1 cRNA injected along with MO2, shows restoration of haemoglobinized cells (d) and complete rescue of the developmental defects of hydrocephalus, body axis curvature, and yolk sac formation (e, arrows).

The phenotypes observed in hrg-1 knockdown embryos suggested an essential role for zebrafish hrg-1 in the specification, maintenance or maturation of the erythroid cell lineage. hrg-1 morphants revealed wild-type levels of βe1–globin mRNA, a marker for haemoglobinization in the developing blood island and intermediate cell mass of embryos at 24 h after fertilization, but by 48 h after fertilization there were no detectable globinproducing cells (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Moreover, markers for myeloid (MPO and Lplastin) and thrombocyte (platelet-equivalent, cd41) lineages were normal in the hrg-1 morphant embryos (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c)17,18. These findings indicate that zebrafish hrg- 1 is not required for cell lineage specification but rather for maintenance and haemoglobinization of the embryonic erythroid cells. Similarly, pax 2.1 mRNA expression, a marker of the midbrain/hindbrain boundary organizer, was severely deficient in the central nervous system of MO2 morphants, indicating that midbrain–hindbrain development in zebrafish is also dependent on hrg-1 (Supplementary Fig. 3d). To verify whether the knockdown phenotypes observed in zebrafish corresponded functionally to the RNAi phenotypes in C. elegans (compare Fig. 2c–e with Fig. 3b, c), we co-injected MO2 in the presence and absence of C. elegans hrg-1 synthetic antisense RNA (cRNA). Despite the modest (21%) sequence identity between the C. elegans and zebrafish HRG-1, more than 85% of the morphant embryos were fully rescued by Cehrg-1 (95 of 108 mutants rescued), in contrast with none for the control embryos (0 of 194 mutants rescued), correcting the defects in anaemia, hydrocephalus and body axis curvature (Fig. 3d, e). These studies suggest that C. elegans and zebrafish HRG-1 have a highly conserved function in modulating haem homeostasis.

To dissect the function of HRG-1 in vertebrates further, we examined its gene expression, intracellular localization and biochemical properties in mammalian cells. Genome database searches with C. elegans HRG-1 identified an orthologous gene, which we refer to as hHRG-1 (Fig. 1e), with about 23% and 65% identity to worm and zebrafish HRG-1 proteins, respectively. hHRG-1 is located on human chromosome 12q13, about 3.2 megabases from DMT1, a gene encoding the main iron transporter in mammals19,20. RNA blotting of human adult tissues and tumour cell lines detected two hHRG-1 transcripts about 1.7 and 3.1 kilobases long, with the shorter form predominant (Fig. 4a, b). hHRG-1 was highly expressed in the brain, kidney, heart and skeletal muscle (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 4a), and moderately expressed in the liver, lung, placenta and small intestine. hHRG-1 was abundantly expressed in cell lines derived from duodenum (HuTu 80), kidney (ACHN, HEK-293), bone marrow (HEL, K562) and brain (M17, SH-SY5Y) (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 4b). Neither altering cellular haem and iron status nor chemically inducing Friend mouse erythroleukaemia (MEL) cells to produce haemoglobin altered HRG- 1 at the transcriptional level in mammalian cells (Supplementary Fig. 5). However, our findings do not exclude the possibility that HRG-1 may be regulated at the post-translational level.

Figure 4. Expression, localization and functional studies of worm and mammalian hrg-1.

a, b, mRNA expression of human HRG-1 in multiple adult human tissues (a) and human tissue-derived cell lines (b). The blots were stripped and reprobed with β-actin as loading control. c, Expression of C-terminally tagged proteins in transfected HEK-293 cells by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting with antibodies against HA (lanes 1–3, 50 µg) and GFP (lanes 4– 6, 25 µg), or by in vitro expression with 35S fluorography (lanes 7–9, one-fifth of total extract). d, Cellular localization of C-terminally tagged fluorescent proteins in transfected HEK-293 cells by confocal microscopy. The plasma membrane (PM) was identified by using wheat germ agglutinin. Scale bar, 20 µm. e, HRG-1 proteins interact with haem as a function of pH. Cell lysates (lanes 1 and 4, one-tenth of total protein) from HEK-293 cells expressing the indicated HA-tagged proteins were incubated with haemin-agarose. Wash (lanes 2 and 5) depicts the final wash before elution of the bound protein (lanes 3 and 6) from the haemin-agarose column. Samples were subjected to SDS–PAGE followed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antisera. f, Flow-cytometry histograms show enhanced ZnMP uptake and accumulation after 30 min of incubation with 5 µM ZnMP in MEL cells stably expressing either hHRG-1–HA (right) or empty vector (left). g, Electrophysiological currents (means ± s.d., n = 4) elicited from Xenopus oocytes injected with cRNA encoding the indicated protein, when clamped at −110 mV in the presence of 20 µM haemin chloride. The y axis represents the difference in current in the presence and absence of haemin, normalized to the current observed in the absence of haem. Values with different letter labels are significantly different (P < 0.05) within each treatment compared with hKv1.1 control. h, Proposed model for the function of HRG-1 proteins in haem homeostasis in C. elegans intestinal cells. CeHRG-4 mediates haem uptake through the plasma membrane, whereas CeHRG-1 facilitates intracellular haem availability through an endosomal and/or lysosomalrelated compartment. The model does not exclude the possibilities that CeHRG-1 traffics through the plasma membrane and may be functional on the cell surface.

To assess the localization and function of HRG-1 protein, C. elegans (Ce)HRG-1, hHRG-1 and CeHRG-4 were tagged at the C terminus with either the haemagglutinin (HA) epitope or GFP variants and transiently transfected into HEK-293 cell lines. All three proteins migrated as a monomer as well as more slowly migrating oligomers (Fig. 4c, lanes 1–6). The oligomerization did not occur in solution after cell lysis or because of protein overexpression, because in vitro transcription and translation revealed a single main radiolabelled band corresponding to the monomer for each protein (Fig. 4c, lanes 7–9). Confocal microscopy studies with cells expressing fluorescently tagged proteins showed HRG-4 clearly on the periphery of cells and localized together with a plasma membrane marker. In contrast, CeHRG-1 and hHRG-1 were distributed in an intracellular compartment punctuated throughout the cytoplasm, with about 10% of the total fluorescence on the cell periphery (Fig. 4d). Co-expression of CeHRG-1 and hHRG-1 in the same cell resulted in more than 80% of the two proteins being localized to the same intracellular sites (Fig. 4d). Confocal studies with cellular organelle markers localized CeHRG-1 and hHRG-1 together with LAMP1 (more than 90%), and partly with rab 7 and rab 11 (about 50–70%; Supplementary Fig. 6). These results suggest that HRG-1 proteins are located primarily in endosomes and lysosomerelated organelles and are consistent with the presence of sorting motifs in HRG-1 (Fig. 1e)11.

The presence of conserved haem-binding amino-acid residues in conjunction with the haem-dependent RNAi phenotype in C. elegans implied that HRG-1 and HRG-4 may interact with haem. Haemin-agarose affinity chromatography performed on cell lysates from transiently transfected HEK-293 cells showed significant binding of CeHRG-4, CeHRG-1 and hHRG-1 to haem (Fig. 4e), whereas little binding was observed for human ZIP4, an eight-transmembrane-domain zinc transporter that localizes to the plasma membrane and perinuclear cytoplasmic vesicles21. Because HRG-1 localized to endosomal–lysosomal organelles whereas HRG-4 is on the plasma membrane, we reasoned that these proteins may bind haem as a function of pH. In a manner consistent with their localization, haem binding to HRG-1 was significantly decreased by increasing the pH, in contrast with HRG-4, which bound haem over a broader pH range (Fig. 4e, lanes 3 and 6). These binding assays, together with the intracellular localization results, correlate directly with the phenotypic differences observed in worms in which hrg-1 and hrg-4 were knocked down by RNAi (Fig. 2c–e).

We next investigated whether HRG-1 proteins mediate haem uptake, by expressing hHRG-1 ectopically in MEL cells. ZnMP uptake or retention was substantially altered in MEL cells constitutively expressing hHRG-1 in comparison with control cells; maximal differences were observed after 30 min of incubation (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 7). To assay haem transport directly, Xenopus laevis oocytes were injected with cRNA and haem-dependent currents were monitored under a two-electrode voltage clamp. Significant inward currents of over 250 nA were observed when 20 µM haem was added to oocytes clamped at −110 mV and injected with cRNA for CeHRG-1, hHRG-1 and CeHRG-4; this is indicative of haem-dependent transport across the plasma membrane (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 8). Together, these results show that the worm and mammalian HRG-1 proteins transport haem.

Given the parallels between copper, iron and haem in their biochemical reactivity and toxicity, we envisage an intricate cellular network of haem homeostasis molecules that bind, transfer and compartmentalize haem6,22,23. We propose a model of haem homeostasis in which CeHRG-4 mediates haem uptake in C. elegans at the plasma membrane, whereas CeHRG-1 regulates intracellular haem availability through an endosomal compartment (Fig. 4h). Haem limitation would induce the uptake and regulated sequestration of an essential, but toxic, macrocycle by the coordinated actions of CeHRG-4 and CeHRG-1 functioning in distinct membrane compartments. Because haems have greater solubility below or above physiological pH, compartmentalization of HRG-1 to an acidic endosome or a lysosomerelated organelle would permit haem to remain soluble. The presence of HRG-1 in both C. elegans and vertebrates suggests that the components for intracellular regulation and movement of haem by means of HRG-1 are conserved in metazoans.

METHODS SUMMARY

C. elegans strains were grown either in liquid mCeHR-2 medium or on Nematode Growth Medium agar plates spotted with E. coli. Cell lines were routinely cultured in basal growth medium composed of DMEM and 10% bovine serum. We maintained zebrafish on a standard genetic AB or Tü wild-type background. For microarray analysis, synchronized F2 larvae were re-inoculated in mCeHR-2 medium supplemented with 4, 20 or 500 µM haemin and harvested at the late L4 stage for hybridization to a Affymetrix C. elegans Whole Genome Array. C. elegans hrg-1 putative promoter was cloned into pPD95.67 to create a hrg-1::gfp transcriptional fusion (strain IQ6011). For RNAi experiments, equal numbers of IQ6011 synchronized F1 L1 larvae were placed on NGM agar plates containing 2 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside and spotted with RNAi feeding bacteria that had been grown in Luria–Bertani broth supplemented or not with haemin for 5.5 h. For GFP measurements, worms were harvested and lysed to quantify GFP fluorescence with an ISS PC1 spectrofluorimeter. Pulldown assays of transfected HEK-293 cells were performed with equivalent amounts of target protein and 300 nmol of haemin-agarose. For confocal microscopy studies, a Zeiss laser scanning LSM 510 equipped with argon and HeNe lasers was used. For zebrafish experiments, whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed with digoxigenin-labelled cRNA probes in accordance with standard protocols. Live embryos at 48–72 h after fertilization were stained for haemoglobinized cells with o-dianisidine. Zebrafish hrg-1 gene rescue assays were performed by injecting 1.5 ng of MO2 morpholino together with 200 pg of C. elegans hrg-1 cRNA. For flow cytometry, MEL cells stably expressing HRG-1 were incubated with 5 µM ZnMP and the fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry. Electrophysiological measurements in Xenopus oocytes injected with cRNA were performed with a two-electrode voltage clamp.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The Hamza laboratory thanks the DC-Baltimore WormClub for advice and criticism. We also thank P. Aplan, H. Dailey, I. Mather and S. Severance for critical discussions and reading of the manuscript; M. Cam and G. Poy for expertise with microarrays; J. Lippincott-Schwartz and D. Hailey for organelle markers; H.-F. Lin and R. Handin for the Tg(CD41–GFP) transgenic zebrafish line; J. Italiano for use of the Orca IIER charge-coupled device camera/Metamorph software; P. Krieg for the pT7TS Xenopus oocyte expression vector; P. Ponka and R. Eisenstein for the SIH iron chelation; D. Beckett for use of the fluorescent spectrophotometer; and M. Petris for the hZIP4 plasmid. Many of the worm strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center. This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (I.H., M.D.F. and B.H.P.), the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation (I.H. and B.H.P.), the NIH/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Intramural Research Program (M.K.), Council for Scientific and Industrial Research and Kanwal Rekhi Fellowships (S.K.U.), and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Undergraduate Science Education Program grant (S.U.).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions Experimental design and execution were as follows: worm experiments and microarrays, A.R., A.U.R., M.K. and I.H.; mammalian experiments, A.R., A.U.R., M.T., C.H., S.U., M.D.F. and I.H.; zebrafish experiments, J.A. and B.H.P.; Xenopus injections and measurements, S.K.U. and M.K.M. I.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Author Information The microarray data have been deposited with the Gene Expression Omnibus at NCBI under accession number GSE8696. Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

References

- 1.Ponka P. Cell biology of heme. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1999;318:241–256. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199910000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaasik K, Lee CC. Reciprocal regulation of haem biosynthesis and the circadian clock in mammals. Nature. 2004;430:467–471. doi: 10.1038/nature02724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yin L, et al. Rev-erbα, a heme sensor that coordinates metabolic and circadian pathways. Science. 2007;318:1786–1789. doi: 10.1126/science.1150179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faller M, et al. Heme is involved in microRNA processing. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:23–29. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medlock AE, Dailey HA. In: Tetrapyrroles. Warren M, Smith AG, editors. Austin, TX: Landes Bioscience and Springer Science + Business Media; 2007. pp. 116–127. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamza I. Intracellular trafficking of porphyrins. Am. Chem. Soc. Chem. Biol. 2006;1:627–629. doi: 10.1021/cb600442b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao AU, Carta LK, Lesuisse E, Hamza I. Lack of heme synthesis in a freeliving eukaryote. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:4270–4275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500877102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dailey HA. Terminal steps of haem biosynthesis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002;30:590–595. doi: 10.1042/bst0300590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nass R, Hamza I. In: Current Protocols in Toxicology. Maines MD, et al., editors. New York: Wiley; 2007. pp. 1.9.1–1.9.17. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanehisa M, et al. From genomics to chemical genomics: new developments in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D354–D357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonifacino JS, Traub LM. Signals for sorting of transmembrane proteins to endosomes and lysosomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003;72:395–447. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt PM, et al. Residues stabilizing the heme moiety of the nitric oxide sensor soluble guanylate cyclase. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2005;513:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pellicena P, et al. Crystal structure of an oxygen-binding heme domain related to soluble guanylate cyclases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12854–12859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405188101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldman BS, Beck DL, Monika EM, Kranz RG. Transmembrane heme delivery systems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:5003–5008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGhee JD, et al. The ELT-2 GATA-factor and the global regulation of transcription in the C. elegans intestine. Dev. Biol. 2007;302:627–645. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shafizadeh E, Paw BH. Zebrafish as a model of human hematologic disorders. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2004;11:255–261. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000138686.15806.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett CM, et al. Myelopoiesis in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Blood. 2001;98:643–651. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin HF, et al. Analysis of thrombocyte development in CD41-GFP transgenic zebrafish. Blood. 2005;106:3803–3810. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleming MD, et al. Microcytic anaemia mice have a mutation inNramp2, a candidate iron transporter gene. Nature Genet. 1997;16:383–386. doi: 10.1038/ng0897-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunshin H, et al. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian proton-coupled metal-ion transporter. Nature. 1997;388:482–488. doi: 10.1038/41343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mao X, et al. A histidine-rich cluster mediates the ubiquitination and degradation of the human zinc transporter, hZIP4, and protects against zinc cytotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:6992–7000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rees EM, Thiele DJ. From aging to virulence: forging connections through the study of copper homeostasis in eukaryotic microorganisms. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2004;7:175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Domenico I, McVey Ward D, Kaplan J. Regulation of iron acquisition and storage: consequences for iron-linked disorders. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:72–81. doi: 10.1038/nrm2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.