Abstract

Motivation: The Expectation–Maximization (EM) algorithm has been successfully applied to the problem of transcription factor binding site (TFBS) motif discovery and underlies the most widely used motif discovery algorithms. In the wider field of probabilistic modelling, the stochastic EM (sEM) algorithm has been used to overcome some of the limitations of the EM algorithm; however, the application of sEM to motif discovery has not been fully explored.

Results: We present MITSU (Motif discovery by ITerative Sampling and Updating), a novel algorithm for motif discovery, which combines sEM with an improved approximation to the likelihood function, which is unconstrained with regard to the distribution of motif occurrences within the input dataset. The algorithm is evaluated quantitatively on realistic synthetic data and several collections of characterized prokaryotic TFBS motifs and shown to outperform EM and an alternative sEM-based algorithm, particularly in terms of site-level positive predictive value.

Availability and implementation: Java executable available for download at http://www.sourceforge.net/p/mitsu-motif/, supported on Linux/OS X.

Contact: a.m.kilpatrick@sms.ed.ac.uk

1 INTRODUCTION

Transcription factor binding site (TFBS) motifs are short DNA sequence patterns that have important roles in genetic transcriptional regulation. These patterns are of considerable interest to biologists, as they are central to understanding the mechanisms of gene expression. The discovery and further analysis of TFBS motifs remains an important and challenging problem in bioinformatics [examples from the recent ENCODE project include Spivakov et al. (2012), Whitfield et al. (2012) and Yip et al. (2012),]; as a result, there is continued interest in developing algorithms for unsupervised discovery of TFBS motifs (Bailey et al., 2010).

The majority of TFBS discovery algorithms are probabilistic algorithms, which search the input data (usually a collection of promoter regions of coregulated genes) for sequences that are statistically over-represented. Deterministic algorithms make up a large proportion of commonly used algorithms for motif discovery. The deterministic Expectation–Maximization (EM) algorithm is one of the earliest probabilistic motif discovery algorithms (Lawrence and Reilly, 1990) and is the basis for a number of others, including the benchmark motif discovery algorithm MEME (Bailey and Elkan, 1994). However, the EM algorithm has several well-known limitations. For example, the EM algorithm is highly sensitive to its starting parameters. Owing to this sensitivity and the use of a local search strategy, the EM algorithm cannot be guaranteed to converge to the global maximum of the likelihood function, instead converging to an insignificant local maximum or saddle point of the likelihood function. In general, the steps of the EM algorithm can become either analytically or computationally intractable in many practical situations.

The stochastic EM (sEM) algorithm is motivated by the limitations of the deterministic EM algorithm, particularly the issues of intractability. Celeux et al. (1995) note that the sEM algorithm is generally more successful than the EM algorithm owing to stochastic perturbations, which allow the sEM algorithm to escape stable fixed points of the EM algorithm such as insignificant local maxima of the likelihood function. In addition to this, retaining the underlying EM dynamics means that the sEM algorithm generally converges in a relatively small number of iterations in comparison with full stochastic methods.

Stochastic variants of the EM algorithm have been applied to motif discovery previously; for example, the SEAM (Bi, 2007) and MCEMDA (Bi, 2009) algorithms. However, the power of sEM in a motif discovery context has not been fully explored. Most notably, these algorithms are limited to the ‘one occurrence per sequence’ (OOPS) model, which places a constraint on the distribution of motif occurrences within the input dataset. Further, algorithms based on stochastic variants of EM have so far not implemented features commonly found in other motif discovery algorithms, including the ability to automatically determine the most likely motif width from a range of plausible values.

In this article, we present MITSU (Motif discovery by ITerative Sampling and Updating), a novel algorithm for TFBS motif discovery that combines a stochastic version of the EM algorithm with a derived dataset, which leads to an improved approximation of the likelihood function. Significantly, this likelihood function is unconstrained with regard to the number of motif occurrences in each input sequence. The algorithm also incorporates MCOIN, an information-based heuristic to automatically determine the most likely motif width (Kilpatrick et al., 2013). MITSU is evaluated quantitatively on realistic synthetic data and several collections of previously characterized prokaryotic TFBS sequences and shown to outperform an EM-based algorithm and the SEAM algorithm, most notably in terms of site-level positive predictive value. The results of additional tests demonstrate that MITSU has significant advantages over current sEM-based approaches for motif discovery.

2 APPROACH

This article implements an approach based on sEM for the purpose of TFBS motif discovery. Given a joint distribution over observed variables X and latent variables Z, governed by parameters θ, the deterministic EM algorithm (Dempster et al., 1977) maximizes the likelihood function with respect to θ. This likelihood function is intractable directly, so two steps are iteratively applied until some convergence criteria are reached to maximize the likelihood function. An initial estimate of the parameters is made, then the E-step calculates the expected value of the log likelihood function, with respect to the distribution of Z conditional on X under the current estimate of the parameters :

| (1) |

In the context of motif discovery, this can be viewed as calculating the probability for each width-w subsequence in the dataset that it is an occurrence of the motif, or equivalently estimating the position of occurrences of the motif within the input dataset. The M-step then evaluates a new estimate of the parameters by maximizing the expected value of the log likelihood function:

| (2) |

In the context of motif discovery, this can be viewed as reestimating the model parameters given the current estimates for the motif position within the input dataset.

Stochastic variations of the EM algorithm first use Monte Carlo methods to draw a set of samples from the current approximation to the conditional predictive distribution , before replacing the integral in the E-step of the EM algorithm Equation (1) with a finite sum over the drawn samples. The modified E-step is thus

| (3) |

The M-Step then requires maximizing the function as before. This particular variation on the EM algorithm is known as the Monte Carlo EM (MCEM) algorithm (Wei and Tanner, 1990).

Stochastic EM (Celeux et al., 1995) can be viewed as a special case of MCEM, where only one sample is drawn at each iteration. In this case, the latent variables Z characterize which one of the mixture components is responsible for each point in the dataset, effectively making a ‘hard’ assignment of data points to mixture components, rather than the probabilistic weightings used by the EM algorithm. In the context of motif discovery, this would assign each data point to either the motif model or the background model. Formally, the sampling step (S-step, analogous to the E-step in EM) of the sEM algorithm replaces the computation of the function in the E-step by the simpler computation of and simulation of a ‘pseudosample’ z(t). The update step (U-step, analogous to the M-step in EM) updates the model parameters θ(t) on the basis of the ‘pseudo-complete sample’ , in the same way as normal.

As noted above, one of the reasons for stochastic variations of EM being generally more successful than EM is that they have the ability to avoid insignificant local maxima of the likelihood function. This is achieved by choosing whether to accept or reject the new set of proposed model parameters in the U-step of the algorithm. Through this accept/reject mechanism, there is a non-zero probability of accepting new model parameters with a lower likelihood than the current parameters at each iteration of the algorithm (Celeux et al., 1995). In contrast, deterministic EM is guaranteed not to decrease the likelihood and so may become trapped in local maxima or saddle points of the likelihood function.

One significant limitation of the SEAM algorithm is that only the OOPS model is implemented. Bi (2007) suggests that the OOPS model may be extended to the two-component mixture (TCM) model (which is unconstrained with regard to the distribution of motif occurrences) by first discovering a motif using the OOPS model, then scanning the input sequences to discover further occurrences. However, this strategy may not be statistically robust. In this article, we take an approach that extends the OOPS model naturally to the ‘zero or one occurrences per sequence’ (ZOOPS) model, based on the original model definitions. We then continue this extension to a model that allows an arbitrary number of motif occurrences in each input sequence, using a previously described cutting heuristic.

3 METHODS

3.1 A sEM density for the OOPS model

The idea underlying existing algorithms for motif discovery, which implement stochastic variants of EM (Bi, 2007, 2009), is to replace the computation and maximization of by the much simpler computation of , drawing a number of samples Z(t) (S-step), followed by an update to θ based on the pseudo-complete samples (X,Z(t)) (U-step). A suitable density to represent an input sequence Xi is required. We begin by confirming that the density used by Bi (2007) to represent an input sequence using the OOPS model is consistent with the OOPS model derived by Bailey and Elkan (1994).

We generalize the expression introduced by Bailey and Elkan (1994) to define the expectation of the missing data for position j in sequence i using the OOPS model as follows:

| (4) |

where Li is defined as the length of input sequence i, and w is defined as the motif width. Although Bi (2007) uses slightly different notation, we confirm that the definition used is equivalent to that of Bailey and Elkan (1994). Defining k as the set of nucleotides, that is, , the conditional probability of sequence i given the hidden variables is defined in both methods as follows:

| (5) |

This may be viewed as the product of two terms: the first calculating the probability of the background positions and the second calculating the probability of the motif positions.

Here, we generalize the expressions used by Bailey and Elkan (1994) to define the joint (log) likelihood function for the OOPS model as follows:

| (6) |

Again, despite notational differences, this can be shown to be equivalent to the expression as defined by Bi (2007).

To define a suitable density to represent an input sequence, Bi (2007) substitutes Equation (5) into Equation (4); cancelling the ‘background’ terms and taking logs for efficiency results in the expression,

| (7) |

where is a normalizing factor such that

Discussion of the sEM S- and U-steps is deferred to the following section, where they are presented in the context of the ZOOPS model.

3.2 Extending sEM to the ZOOPS model

Here, we follow a similar method to derive an expression representing a sequence in the ZOOPS model. The ZOOPS model, introduced by Bailey and Elkan (1994), assumes that the input sequences contain ‘zero or one occurrences per sequence’. The ZOOPS model requires an indicator variable that denotes whether a particular input sequence contains a motif occurrence. Here, the indicator variable Qi is defined as . That is, Qi = 1 if sequence i contains a motif occurrence and 0 otherwise. The conditional likelihood for a sequence containing a motif occurrence remains the same [Equation (5)]. The conditional likelihood for a sequence that does not contain a motif occurrence is now defined as follows:

| (8) |

Defining an additional variable γ as the prior probability of a motif occurring in a sequence and assuming a uniform prior distribution for motif occurrences within a sequence, it follows that the prior probability of a position in sequence i being a motif start site is

| (9) |

For simplicity, the model parameters are now collected and denoted as . It is noted that the model parameters now include the prior probability of a sequence containing a motif occurrence, in addition to the motif and background models from the OOPS model. It can be shown that the log likelihood function for the complete data in the ZOOPS model can be generalized as follows:

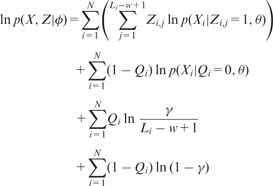

|

(10) |

The expectation of the missing data for the ZOOPS model is therefore

| (11) |

It can be shown that substituting Equations (5) and (8) into Equation (11) as required, then cancelling terms yields

| (12) |

our expression representing a sequence in the ZOOPS model.

The S-step of the sEM algorithm is implemented as described previously (Bi, 2007), drawing a sample from Equation (12) for each input sequence . The U-step of the sEM algorithm requires the construction of a proposal model θ′ based on the samples from the S-step. The parameter updates provided by Bi (2007) are altered here to account for the fact that not every sequence may contain a motif occurrence. The expected values of the Qi variables are used to weight the samples from each sequence i. Here we define the parameters of our proposal model as

| (13) |

for and . The parameters of the background model are not updated, but could be reestimated if required. is a vector of pseudocounts, equivalent to a Dirichlet prior distribution. We also require an update for the other parameter γ. It can be shown that the proposal value for the fraction of sequences containing a motif occurrence is just that, based on the values of calculated in the S-step:

| (14) |

As in SEAM (Bi, 2007), the Metropolis algorithm is used to decide whether to keep our updated parameters. The energies of the current and proposal models, and , respectively, are calculated (how this is done is described in Section 3.4) and the change in energy calculated:

| (15) |

The Metropolis ratio is defined as

| (16) |

A random number is drawn and the parameters updated to the proposal parameters only if u is less than or equal to the Metropolis ratio, that is,

| (17) |

for and and

| (18) |

3.3 Removing the ZOOPS constraint

The ZOOPS model still enforces constraints on the distribution of motif occurrences; it is assumed that each input sequence contains at most one occurrence of a motif. However, there are many biological examples of promoter sequences that contain multiple copies of the same TFBS (Bembom et al., 2007). This is the primary motivation for the TCM model introduced by Bailey and Elkan (1994), which allows an arbitrary number of non-overlapping motif occurrences in each input sequence.

The likelihood function for the TCM model is more computationally complex than those for the OOPS and ZOOPS models. As a result, exact methods based on the TCM model have been avoided in favour of more tractable approximations (Bembom et al., 2007). The TCM model proposed by Bailey and Elkan (1994) uses a derived dataset consisting of all overlapping subsequences of width w from the original dataset. Some proportion of these subsequences are motif occurrences; the remainder are background. While the subsequences in this derived dataset are necessarily overlapping, the likelihood function is based on a sample of independent sequences (Bembom et al., 2007). An additional smoothing step is required to reduce the degree to which two overlapping subsequences can both be assigned to the motif component of the model.

Keles et al. (2003) propose an alternative cutting heuristic, which involves deriving a different dataset from the original, then applying the ZOOPS model to each of the derived sequences. The main advantages of this method are that no additional steps are required to deal with the assumption of independence, and the approximation to the likelihood function is improved. This method is improved by Bembom et al. (2007) and we implement a similar method here. Briefly, the original dataset is cut into subsequences of a given length U, such that each subsequence contains the first (w − 1) positions of the next subsequence. The ZOOPS model is then applied to this derived dataset. The previous studies implementing this heuristic have shown that the method is fairly robust with respect to the choice of cut length U but have suggested that this parameter may be optimized using cross-validation (Bembom et al., 2007; Keles et al., 2003). Here, the cut heuristic is implemented as an inner loop within the motif discovery algorithm (Section 3.5). The ZOOPS model is applied to derived datasets with varying values of U, and the parameter settings that yield the highest energy value are returned as the best motif model. We show in Section 4.3 that the cut heuristic in combination with the ZOOPS model successfully allows discovery of multiple copies of the same motif within a single input sequence, in the context of motif discovery using sEM.

3.4 Defining an energy function

The original energy function used in the SEAM algorithm (Bi, 2007) becomes problematic when used with the cut heuristic used to implement discovery of multiple motifs within a single input sequence. The main problem stems from the fact that the energy function

| (19) |

is scaled by the number of input sequences N; this is assumed to be constant in the SEAM algorithm and means that energies cannot be compared between datasets with differing values of N. Using the cutting heuristic means that the value of N may double, or triple, depending on the cut length (U). A way of fairly comparing motif energies is required. We are further interested in the properties of the energy function, particularly how it varies with changing motif conservation and varying values of γ. Here, we propose a modification to the original energy function such that

| (20) |

This modified energy function is maximized with a perfectly conserved motif occurring in each input sequence, and the γN factor cancels in the case of datasets derived by the cut heuristic. It can be shown that the following useful properties hold:

If two motifs are perfectly conserved, the motif with the higher number of occurrences will have a higher energy.

Given two motifs of equal prevalence and unequal motif conservation, the motif discovery algorithm will tend to discover the motif with the higher energy (equivalently, the higher motif conservation).

All else being equal, a higher proportion of sequences containing a motif occurrence will yield a higher energy.

We adopt this modified energy function in MITSU but note that other alternative energy functions may be possible; because the sEM accept/reject mechanism is based on a difference of energies, substituting other energy functions based on the model entropy should have little effect on this mechanism.

3.5 MITSU algorithm

The pseudocode of MITSU is given as follows:

procedure MITSU algorithm

create Markov background model

for w = wmin to wmax do

for cut length in {set of cut lengths}do

for n random seeds do

for γ = to 1 by × 2 do

run sEM on cut dataset using ZOOPS model at width w:

until convergence do

S-step (Equation 12)

U-step (Equations 13–18)

end

end

end

return the best motif model over n random seeds & varying γ

end

return the best motif model over all cut lengths

end

estimate most likely width using MCOIN

return motif model and list of predicted sites for

end MITSU algorithm

Although satisfactory convergence results for sEM and related algorithms have been obtained (Diebolt and Robert, 1990, 1994), designing a stopping rule for sEM is challenging; Jank (2005) notes that a simple deterministic stopping rule may be triggered by what is a chance fluctuation stemming from the S-step of the algorithm. Following the recommendations of Booth and Hobert (1999), we implement a deterministic stopping rule for several iterations to reduce the chance of a premature stop. After each iteration, the Euclidean distance between the previous and current motif models is calculated. If this distance is below a given threshold for three successive iterations, the algorithm is deemed to have converged; we choose the threshold here as 10−3. Stochastic EM generally takes longer to converge than deterministic EM (on tests with the CRP dataset used in Section 4.3, deterministic EM was approximately five times faster than MITSU, based on testing 1000 random seeds). However, as noted above, sEM usually converges faster than full stochastic methods. We accept this longer running time in exchange for increased accuracy in terms of predicted motif occurrences. We compare the convergence of MITSU with that of deterministic EM in Section 4.2.

Motif occurrences are predicted using a Bayes-optimal classifier that has been described previously by Bailey and Elkan (1994). Following the ZOOPS model, we predict at most one motif occurrence per sequence in the cut dataset; the cut heuristic means that more than one occurrence per sequence may be predicted when these predictions are mapped back to the original dataset.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Here, we summarize and discuss the results of a number of tests that illustrate the advantages of a sEM-based approach for motif discovery and the performance advantages of MITSU in particular. Algorithmic performance is assessed through mean site-level sensitivity (sSn), mean site-level positive predictive value (sPPV) and the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC). These measures are commonly used to assess the performance of motif discovery algorithms, for example, in the studies of Hu et al. (2005) and Tompa et al. (2005). Following these studies, a predicted motif site is defined as a true-positive result if it overlaps the true site by at least a quarter of the motif width.

4.1 Stochastic EM outperforms deterministic EM

MITSU was evaluated quantitatively using a mixture of realistic synthetic and previously characterized real data. Datasets were constructed as described previously (Kilpatrick et al., 2013). Briefly, five large data collections each consisting of 1000 datasets were constructed using synthetic motifs of varying conservation and realistic Escherichia coli background sequence extracted from the EcoGene database (Rudd, 2000). A sixth data collection consisting of 20 datasets was constructed using known E.coli TFBS sequences extracted from RegulonDB (Gama-Castro et al., 2011). Finally, a data collection consisting of nine datasets was constructed using known TFBS motif sequences from diverse prokaryotic species. These motif sequences were discovered by ChIP methods. Background sequences for these datasets were constructed using synthetic data, altering the probability of choosing each nucleotide to reflect the species GC-content as required. Tables 1–3 summarize the results of the tests on these data collections. For comparison, we also include the results of a deterministic EM-based motif discovery algorithm (Kilpatrick et al., 2013) and SEAM. AUC results are not available for SEAM, as constructing a ROC curve requires ordering all subsequences according to their probability of being a motif occurrence. This is not possible in SEAM as a result of the method of prediction used.

Table 1.

Realistic synthetic data: classification results

| Conservation (mean bits/col) | Deterministic EM |

SEAM |

MITSU |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sSn | sPPV | AUC | sSn | sPPV | AUC | sSn | sPPV | AUC | |

| 2.00 | 0.84 | 0.25 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | — | 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.97 |

| 1.49 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.93 | — | 0.90 | 0.97 | 1.00 |

| 1.08 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.96 | 0.49 | 0.49 | — | 0.68 | 0.77 | 0.99 |

| 0.76 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.94 | 0.09 | 0.09 | — | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.94 |

| 0.51 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.93 | 0.06 | 0.06 | — | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.93 |

Note: sSn, sPPV and AUC for five collections of realistic synthetic data with varying levels of motif conservation. Best results are printed in bold. In these tests, motif discovery was carried out only at the known motif width.

Table 2.

Escherichia coli data: classification results

| Conservation(mean bits/col) | Deterministic EM |

SEAM |

MITSU |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sSn | sPPV | AUC | sSn | sPPV | AUC | sSn | sPPV | AUC | |

| ‘High’ (1.36) | 0.81 | 0.22 | 0.96 | 0.67 | 0.67 | — | 0.54 | 0.75 | 0.98 |

| ‘Low’ (0.78) | 0.63 | 0.41 | 0.96 | 0.65 | 0.65 | — | 0.57 | 0.71 | 0.97 |

| Overall (1.13) | 0.74 | 0.30 | 0.96 | 0.66 | 0.66 | — | 0.55 | 0.73 | 0.98 |

Note: sSn, sPPV and AUC for 20 datasets created using previously characterized E.coli TFBS sequences. Best results are printed in bold. In these tests, motif discovery was carried out only at the experimentally determined motif width.

Table 3.

Diverse prokaryotic data: classification results

| Conservation (mean bits/col) | Deterministic EM |

SEAM |

MITSU |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSn | Sppv | AUC | sSn | sPPV | AUC | sSn | sPPV | AUC | |

| 0.99 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.99 | 0.86 | 0.86 | — | 0.88 | 0.92 | 1.00 |

Note: sSn, sPPV and AUC for nine datasets created using real prokaryotic data determined through ChIP experiments. Best results are printed in bold. In these tests, motif discovery was carried out only at the experimentally determined motif width.

4.1.1 Realistic synthetic data

Based on the results on realistic synthetic data shown in Table 1, we note that sSn and sPPV decrease with decreasing motif conservation for all three tested algorithms. We have noted this behaviour previously in deterministic EM (Kilpatrick et al., 2013) and attribute the decrease in sSn to fewer sites being predicted overall and the decrease in sPPV to the background sites better matching the motif sites as conservation decreases, leading to an increase in the number of false-positive results.

We note that, in the majority of tests, the results of MITSU outperform those of both the deterministic EM algorithm and SEAM, particularly with regard to sSn and sPPV. The increased performance at lower levels of motif conservation is particularly notable. The success of MITSU is attributable to making fewer, but more accurate, predictions. The predictions made are generally more cautious; previous false-positive predictions are now more likely to be classified as true-negative predictions. This significant reduction in the number of false-positive predictions explains the large increase in the sPPV values.

We also note that the sSn and sPPV results for the sEM-based algorithms are less biased. The results for the deterministic EM algorithm, particularly at high levels of motif conservation, are skewed towards increasing sSn; that is, fewer false-negative predictions were made at the expense of having more false-positive predictions. SEAM and MITSU are more unbiased in this respect, producing fewer false predictions in general.

4.1.2 Escherichia coli and prokaryotic ChIP data

Tables 2 and 3 present the results of tests on previously characterized E.coli TFBS sequences and TFBS sequences from diverse prokaryotes determined by ChIP experiments, respectively. The general trend remains the same: both sSn and sPPV decrease with decreasing motif conservation. We have reported previously that deterministic EM-based motif discovery achieves better classification results on previously characterized E.coli data than could be expected given realistic synthetic data of a similar conservation (Kilpatrick et al., 2013). Again, we attribute this improvement in performance to the differences in motif structure. Whereas the conservation of the synthetic motifs used here is independent of position, Eisen (2005) notes that real TFBS motifs with low mean conservation often have clusters of well-conserved positions; we believe that differences in the distribution of high and low conservation across true motifs in comparison with synthetic motifs explains the improvement in performance on real data. We note a similar trend here with the results of SEAM and MITSU, particularly at lower levels of motif conservation.

As with the realistic synthetic data, MITSU is shown to increase sPPV by making fewer, more accurate, predictions (Table 2). We note that the sSn values are decreased to lower than the corresponding values from deterministic EM and (to a lesser extent) SEAM. This is a side effect of predicting fewer sites overall: ‘borderline’ predictions that may have been classified as true-positive results previously are now classed as false-negative results owing to the more cautious predictor. However, as with the realistic synthetic data results, we note that the sSn and sPPV values for MITSU are now less biased. Although MITSU uses a Bayes-optimal classifier for site prediction, the results of the E.coli tests here suggest that a better balance between sSn and sPPV may be achieved with a different predictor. However, we note that the complexity of the computational problem and the wide structural variety of TFBS motifs may mean that it is not possible to improve on all measures in all cases.

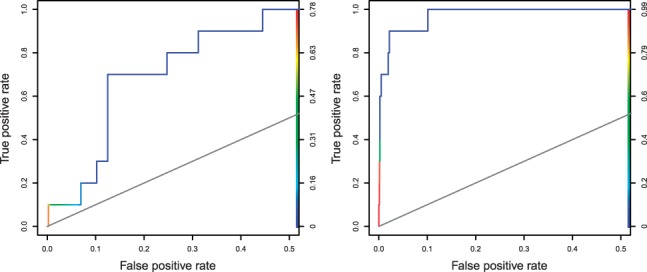

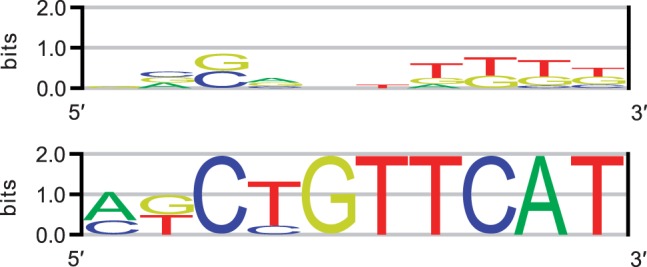

MITSU is shown to be particularly effective in cases where the deterministic EM-based algorithm returned poor results. Figure 1 displays ROC curves for the E.coli TorR motif as discovered by both the deterministic EM and MITSU algorithms. This motif was poorly discovered by the deterministic EM algorithm (sSn = 0.10, sPPV = 0.03, AUC = 0.83); however, MITSU increases performance over all measures (sSn = 0.30, sPPV = 0.50, AUC = 0.98). As noted above, the significant improvement in sPPV is attributable to predicting fewer sites overall, reducing the number of false-positive results. In this case, the improvement in sSn is a result of an improved motif model, which better fits the known occurrences. Sequence logos representing the motifs discovered by both algorithms are shown in Figure 2. Similar improvements in performance are also seen for the E.coli FruR and RscB motifs.

Fig. 1.

ROC curves (plotted for 0 ≤ sFPR ≤ 0.5) for the E.coli TorR motif discovered by the deterministic EM algorithm (left) and MITSU (right). Curve colour illustrates the threshold of , from highest (red) to lowest (blue)

Fig. 2.

Sequence logos representing the E.coli TorR motif as discovered by the deterministic EM algorithm (top) and MITSU (bottom)

Table 3 shows that for the diverse prokaryotic motifs, MITSU outperforms deterministic EM and SEAM in terms of all three performance measures. We note that the increase in sPPV is most significant. This result may be of particular interest to biologists, as it means that fewer false-positive results are predicted: sites which are predicted now are therefore more likely to be true TFBS occurrences. As with the E.coli motifs above, we notice significant increases in performance for motifs that were relatively poorly discovered by deterministic EM, for example, the E.coli CRP and RutR motifs and the Bacillus subtilis Spo0A motif.

Further tests were carried out in which the MCOIN heuristic was used to determine the most likely motif width from a range of plausible widths (±4 bp of the experimentally determined motif width). When the true motif width is unknown, the performance of MITSU is decreased slightly; the overall results on the E.coli dataset and the diverse prokaryotic dataset when using the MCOIN heuristic (sSn = 0.43, sPPV = 0.68, AUC = 0.97 and sSn = 0.85, sPPV = 0.88, AUC = 1.00, respectively) show that MITSU continues to outperform both deterministic EM and SEAM in terms of sPPV and AUC, but decreases in sensitivity compared with the previous results (Tables 2 and 3).

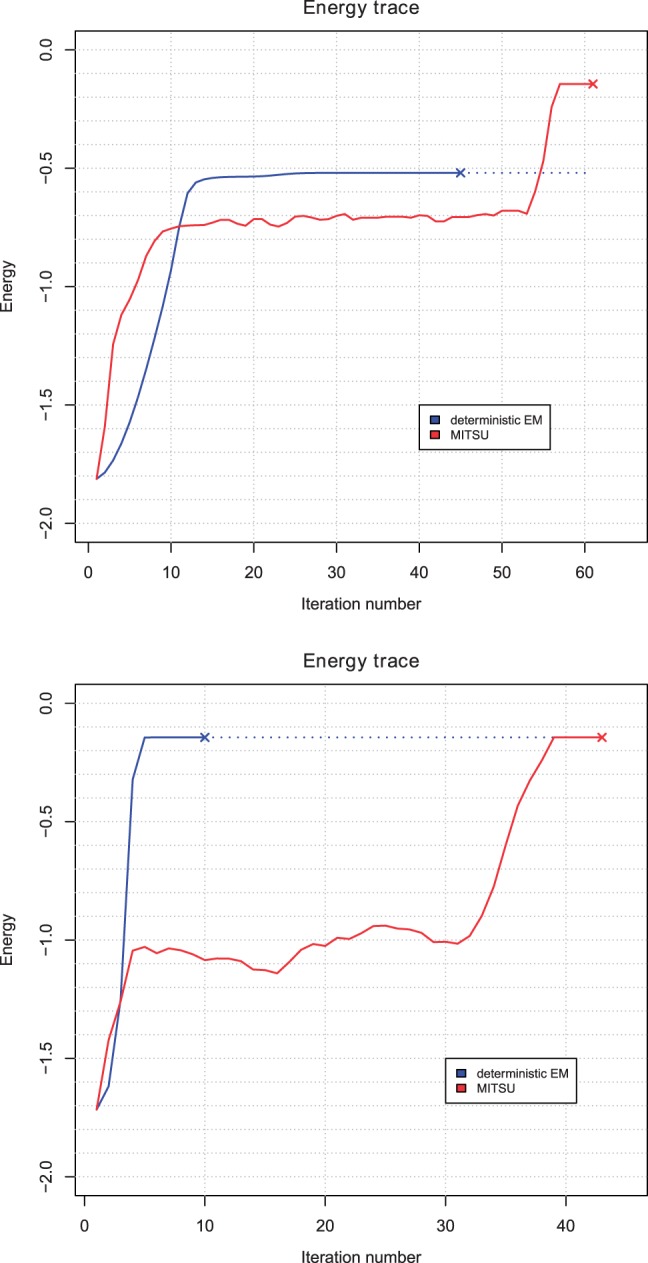

4.2 Stochastic EM escapes local maxima

One major motivation for the sEM algorithm is the fact that the deterministic EM algorithm cannot be guaranteed to converge to the global maximum of the likelihood function and may instead converge to a saddle point or local maximum of the likelihood function. While sEM also cannot be guaranteed to converge to the global maximum of the likelihood function, it can be demonstrated that the stochastic perturbations of sEM allow sEM-based algorithms to escape local maxima, which trap deterministic EM-based algorithms, in a motif discovery context.

We construct a dataset comprising 10 sequences of 200 nt in length, each sequence containing a single occurrence of a perfectly conserved motif of width 8 bp. As before, E.coli intergenic sequences extracted from EcoGene were used as background positions. Despite the relative simplicity of the dataset, we expect that there will be a large number of local maxima in the likelihood function, corresponding to patterns that are better conserved than the background but less well conserved than the motif of interest.

Energy traces for two runs of both the deterministic EM algorithm and MITSU are shown in Figure 3. Both algorithms are initialized with the same parameter values and allowed to run to convergence. Both traces illustrate one of the major differences between deterministic and sEM: while each iteration of deterministic EM is guaranteed not to decrease the likelihood, sEM has a non-zero probability of accepting new model parameters that decrease the likelihood, to escape local maxima of the likelihood function. The top trace illustrates a case where deterministic EM converges to a local maximum at around . In contrast, although sEM spends ∼40 iterations around , a small jump that decreases energy at iteration 53 is followed by several iterations, which dramatically increase the energy. Using our stopping rule, sEM converges at , the energy corresponding to perfect discovery of the known motif. The lower trace in Figure 3 shows a case where both algorithms converge to . This trace illustrates that deterministic EM generally converges faster than sEM, which can spend a relatively large number of iterations exploring lower energies before converging. However, we see this slower convergence as a small trade-off in exchange for more accurate motif models and binding site predictions, as shown in the top energy trace.

Fig. 3.

Energy traces for two runs of both the deterministic EM algorithm (blue) and MITSU (red) on a synthetic dataset containing a perfectly conserved motif of width 8 bp. Algorithm convergence is marked with ‘×’ in both cases. We note that the sEM algorithm allows MITSU to escape local maxima of the likelihood function, which can trap deterministic EM (top)

4.3 MITSU successfully discovers multiple motifs in a single sequence

As noted in Section 3.3, the cut heuristic in combination with the ZOOPS model allows discovery of multiple motif occurrences within a single input sequence. We present a proof of principle using the well-known CRP dataset, used by Bi (2007), Lawrence et al. (1993) and Stormo and Hartzell (1989), among others. Briefly, CRP is a prokaryotic transcription factor that is important in the regulation of genes involved in energy metabolism. The CRP dataset consists of 18 sequences, each of which is 105 nt in length. The dataset contains 24 CRP binding sites determined by footprinting experiments or sequence similarity to confirmed binding sites; each sequence in the dataset contains one or two sites. Each binding site is 22 bp in length. Figure 4 (top) shows the CRP motif sequence logo constructed from the 24 binding sites in the dataset; we note that the low conservation and gapped nature of the CRP motif increases the challenge of computational discovery.

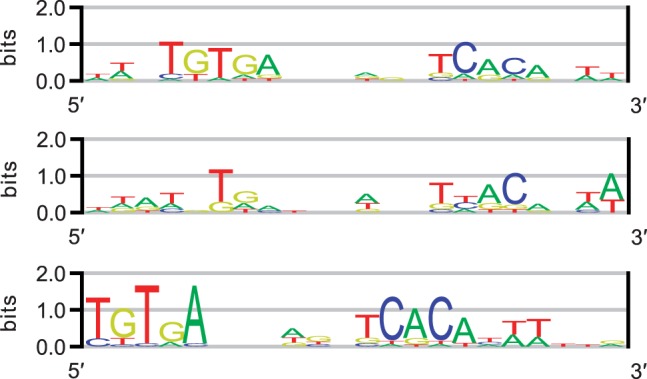

Fig. 4.

CRP motif sequence logos. From top: logo constructed from the 24 binding sites contained in the CRP dataset; logo representing the motif discovered by MITSU; logo representing the motif discovered by MEME when the number of known sites was not provided

We compare MITSU against MEME and assume that the true motif width is known; both algorithms are run at this width. MITSU was run with the cut length U equal to half the length of each input sequence. The results of this test show that MITSU predicted 28 binding sites (sSn = 0.71, sPPV = 0.61, AUC = 0.99) and successfully predicted both binding sites in the CE1CG, ARA and LAC sequences. The middle logo in Figure 4 represents the motif discovered by MITSU. Based on this result, MITSU compares well with MEME, which predicted 18 binding sites and failed to discover more than one site in a sequence using the TCM model when the total number of sites was not provided (sSn = 0.71, sPPV = 0.94). Fourteen of the sites predicted by MEME were also predicted by MITSU. The bottom logo in Figure 4 represents the motif discovered by MEME when the number of known sites was not provided. This motif is shifted by 3 bp compared with the motif constructed from the known binding sites. When the total number of sites was used as additional information, MEME predicted 24 binding sites and successfully predicted both binding sites in the CE1CG, DEOP2 and MALK sequences (sSn = sPPV = 0.83). Sixteen of the sites predicted by MEME were also predicted by MITSU.

Comparing the sequence logos representing the motifs discovered by MITSU and MEME shown in Figure 4, we note that the positions in the motif discovered by MITSU are generally underweighted compared with the known motif and that the positions in the motif discovered by MEME are generally overweighted. This difference in weighting is due to the number of sites predicted by each algorithm. Both algorithms return the same number of true-positive predictions; the number of false-negative predictions is also equal, leading to identical sSn results. MITSU predicts more false-positive sites than MEME, which leads to an underweighting of the positions in the model discovered by MITSU compared with that discovered by MEME. This also provides an explanation for the decreased sPPV result (0.61 versus 0.94, respectively). While there is room for improvement, the cutting heuristic is shown to successfully reproduce the TCM model in principle without additional heuristic optimizations to improve performance.

5 CONCLUSION

Computational discovery of TFBS motifs remains an important and challenging problem in bioinformatics. MITSU is a novel algorithm for motif discovery, based on sEM. MITSU has a clear advantage over deterministic algorithms in that it is less likely to converge to insignificant local maxima of the likelihood function owing to the sEM algorithm, improving results. We show that the sEM algorithm allows MITSU to escape these local maxima and converge to models with higher energies. MITSU also has advantages over existing sEM-based motif discovery algorithms as it is unconstrained with regard to the distribution of motif occurrences within the input dataset and incorporates useful features commonly found in modern motif discovery algorithms, such as automatic determination of motif width.

Results of tests on several collections of realistic synthetic data and two collections of previously characterized prokaryotic data show that MITSU consistently outperforms deterministic EM and the SEAM algorithm for motif discovery in terms of site-level positive predictive value and generally performs at least as well in terms of overall correctness of results, based on ROC analysis. We note that the results returned by MITSU also often increase site-level sensitivity. Using the well-known CRP dataset, we demonstrate that MITSU combines a cut heuristic with the ZOOPS model to effectively reproduce a TCM model without the compromise of additional ‘smoothing’ steps.

Future work will implement probabilistic (or ‘soft’) erasing to discover multiple different motifs within a single dataset and will investigate exploiting the Metropolis accept/reject mechanism to incorporate relevant model-level biological knowledge. Such heuristics will be important in further optimizing performance, as is the case for established motif discovery algorithms.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Funding: Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (Doctoral Studentship to A.M.K.) and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (grant number BB/I023461/1 to S.A. and A.M.K.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Bailey TL, Elkan C. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc. Int. Conf. Intel.l Syst. Mol. Biol. 1994;2:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TL, et al. The value of position-specific priors in motif discovery using MEME. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:179. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bembom O, et al. Supervised detection of conserved motifs in DNA sequences with cosmo. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2007;6 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1260. Article 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi C. SEAM: a stochastic EM-type algorithm for motif-finding in biopolymer sequences. J. Bioinform. Comput. Biol. 2007;5:47–77. doi: 10.1142/s0219720007002527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi C. A Monte Carlo EM algorithm for de novo motif discovery in biomolecular sequences. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2009;6:370–386. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2008.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth JG, Hobert JP. Maximizing generalized linear mixed model likelihoods with an automated Monte Carlo EM algorithm. J. R. Stat. Soc. B Methodol. 1999;61:265–285. [Google Scholar]

- Celeux G, et al. On stochastic versions of the EM algorithm. 1995 Rapport de Recherche-Institut National de Recherche en Informatique et en Automatique, No 2514. [Google Scholar]

- Dempster A, et al. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J. R. Stat Soc B Methodol. 1977;39:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Diebolt J, Robert C. 1990. Bayesian estimation of finite mixture distributions: part II, sampling implementation. Technical Report, 111. Laboratoire de Statistique Théorique et Appliquée, Université Paris VI. [Google Scholar]

- Diebolt J, Robert C. Estimation of finite mixture distributions through Bayesian sampling. J. R. Stat Soc B Methodol. 1994;56:363–375. [Google Scholar]

- Eisen M. All motifs are NOT created equal: structural properties of transcription factor-DNA interactions and the inference of sequence specificity. Genome Biol. 2005;6:P7. [Google Scholar]

- Gama-Castro S, et al. RegulonDB version 7.0: transcriptional regulation of Escherichia coli K-12 integrated within genetic sensory response units (Gensor Units) Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Suppl. 1):D98–D105. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, et al. Limitations and potentials of current motif discovery algorithms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:4899–4913. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jank W. Stochastic variants of EM: Monte Carlo, Quasi-Monte Carlo and more. Proc. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Keles S, et al. Supervised detection of regulatory motifs in DNA sequences. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2003;2 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1015. Article 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick AM, et al. MCOIN: a novel heuristic for determining transcription factor binding site motif width. Algorithms Mol. Biol. 2013;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1748-7188-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence CE, Reilly AA. An expectation maximization (EM) algorithm for the identification and characterization of common sites in unaligned biopolymer sequences. Proteins. 1990;7:41–51. doi: 10.1002/prot.340070105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence CE, et al. Detecting subtle sequence signals: a Gibbs sampling strategy for multiple alignment. Science. 1993;262:208–214. doi: 10.1126/science.8211139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd KE. EcoGene: a genome sequence database for Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:60–64. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spivakov M, et al. Analysis of variation at transcription factor binding sites in Drosophila and humans. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R49. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-9-r49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormo GD, Hartzell GW. Identifying protein-binding sites from unaligned DNA fragments. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:1183–1187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.4.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompa M, et al. Assessing computational tools for the discovery of transcription factor binding sites. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:137–144. doi: 10.1038/nbt1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei GC, Tanner M. A Monte Carlo implementation of the EM algorithm and the poor man’s data augmentation algorithms. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1990;85:699–704. [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield T, et al. Functional analysis of transcription factor binding sites in human promoters. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R50. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-9-r50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip K, et al. Classification of human genomic regions based on experimentally determined binding sites of more than 100 transcription-related factors. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R48. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-9-r48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]