Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate choroidal thickness with spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SDOCT) in subjects with retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) tear as compared with the choroidal thickness of their fellow eye.

Methods

For this cross sectional investigation, 7 eyes of 7 patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration and RPE tear in one eye imaged with SDOCT were identified. Choroidal thickness was measured from the posterior edge of the retinal pigment epithelium to the choroid/sclera junction at 500-μm intervals up to 2500 μm temporal and nasal to the fovea in both the eye with the RPE tear and the eye with intact RPE. All measurements were performed by 2 independent observers and averaged for the purpose of analysis. Measurements were compared using paired t-test.

Results

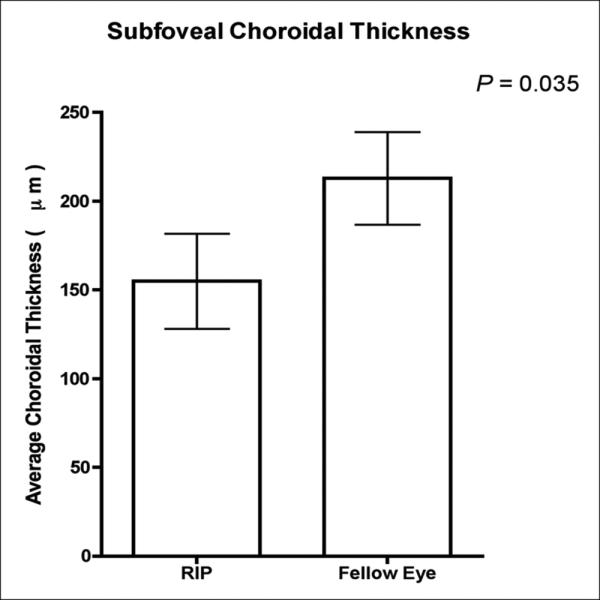

The average age of patients was 79 years (range 66-88). All subjects had dome-shaped pigment epithelial detachments (PED) prior to RPE tear and no dome-shaped PED in the unaffected eye. Average subfoveal choroidal thickness in the eye with the RPE tear was 154.9µm ± 10.1µm. Average subfoveal choroidal thickness in the eye with intact RPE was 212.9µm ± 10.6µm (p=0.035).

Conclusion

There is a significant decrease in subfoveal choroidal thickness in subjects with RPE tear as compared with their fellow eye with intact RPE. It is unclear if this thinning is a consequence of or precedes the RPE tear. Further studies are necessary to prospectively follow choroidal thickness in subjects with dome-shaped PED.

Keywords: choroidal thickness, retinal pigment epithelial tear, spectral domain optical coherence tomography

Introduction

Retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) tears were first described by Hoskin et al in association with wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD) complicated by pigment epithelial detachment (PED).13 Subsequently, RPE tears have been noted to be associated with central serous chorioretinopathy, angioid streaks, idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy, trauma, and age related macular degeneration.14-18 RPE tears have also been described to occur following various treatments for neovascular AMD such as laser photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy, and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF).24-36

RPE tears have been postulated to occur secondary to weakened intercellular connections between RPE cells that can develop following pigment epithelial detachment formation. Tears have a propensity for developing at the base of the PED near the junction of the detached and attached RPE and also at the temporal edge of the PED.19

The choroid is a highly vascular structure that fulfills the critical role of providing nourishment to the outer layers of the retina and RPE. Anatomically, the choroid is separated from the RPE only by a thin layer termed Bruch's membrane. Thus, alterations in choroidal structure and function can lead to dysfunction of the RPE and can play a role in many pathological processes.24-45

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) uses low coherence interferometry of light to examine the retina in vivo and enables visualization of the retina on a micron scale.6-7 Sufficient data regarding the OCT imaging characteristics of the choroid in these diseased states is lacking secondary to its posterior location and the presence of pigmented cells in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) which attenuates incident light. Recent advances using spectral domain OCT (SDOCT) technology make visualization of the choroid feasible using image averaging and enhanced depth imaging (EDI). Changes in choroidal thickness measured using SDOCT have been described in age related macular degeneration, choroidal melanoma, central serous chorioretinopathy, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada and many others.3, 5-10

The purpose of this study is to evaluate choroidal thickness with SDOCT in subjects with RPE tear as compared with the choroidal thickness of their fellow eye without RPE tear.

Methods

For this cross sectional investigation, 7 eyes of 7 patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration and RPE tear in one eye were identified at the New England Eye Center between 2009 to 2011. All patients underwent a complete ophthalmic examination at New England Eye Center, including a slit-lamp examination and dilated fundus biomicroscopy. Each patient also underwent imaging with the Cirrus HD-OCT (Software version…Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin...). This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Tufts Medical Center. Inclusion criteria required the presence of a RPE tear in one eye, and the absence of it in the contralateral eye. All patients with concomitant ocular pathologies, including diabetic retinopathy, vascular occlusions, clinically significant macular edema, primary open angle glaucoma, and corneal disease including Fuchs’ Dystrophy were excluded. Data from normal subjects was included from another study which measured choroidal thickness in 42 eyes of 42 healthy subjects.12 These subjects had no history of retinal or choroidal pathology, and patients with myopic refractive error of greater than 6.0 diopters were excluded.

Cirrus HD 1-line raster scans were used to obtain the measurements of choroidal thickness. These images were not inverted to bring the choroid adjacent to zero delay as image inversion utilizing Cirrus software results in a low-quality image. Choroidal thickness was manually measured from the posterior edge of the retinal pigment epithelium to the choroid/sclera junction at 500-μm intervals up to 2500 μm temporal and nasal to the fovea in both the eye with the RPE tear and the eye with intact RPE (figure 1). All measurements were performed by 2 independent observers and averaged for the purpose of analysis. This method has been previously described.12

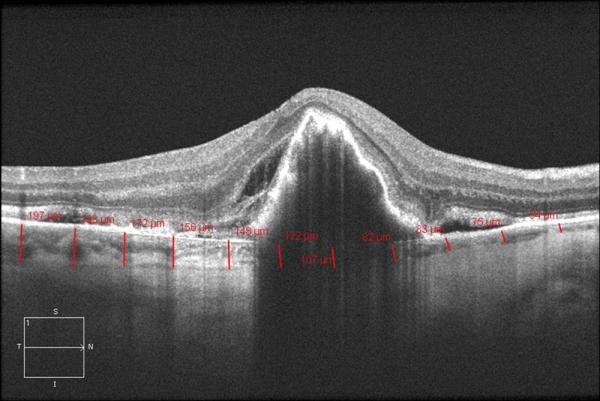

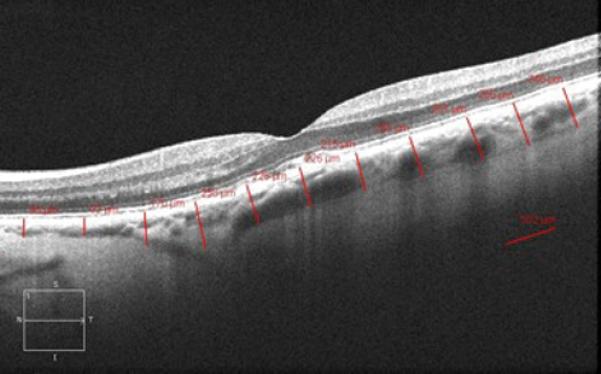

Figure 1.

Cirrus HD 1 line raster of the macula in a patient with an RPE tear OD (A.) and intact RPE OS (B.).

Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post test comparison with Bonferroni's Multiple Test. A 95% confidence interval and a 5% level of significance were adopted; therefore, the results with a P-value less than or equal to 0.05 were considered significant. All statistics were calculated using Graph Pad Prism 5.0 software for Mac.

Results

A total of 7 eyes of 7 patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration and RPE tear in one eye were included in this study. The average age of these patients was 79 years (range 66-88). Of these subjects, 3 were male and 4 were female. In addition to exudative macular degeneration, the only other ocular comorbidity shared by these patients was the presence of nuclear sclerotic cataracts. Five patients had bilateral nuclear sclerotic cataracts. Two patients had a unilateral nuclear sclerotic cataract and uncomplicated cataract surgery with posterior chamber lens placement in the contralateral eye.

All subjects had dome-shaped pigment epithelial detachments (PED) prior to RPE tear and no dome-shaped PED in the unaffected eye. Four patients had bilateral neovascular age-related macular degeneration and three patients had dry age-related macular degeneration in the fellow intact eye with no dome-shaped PED. Five eyes with dome-shaped PED had active choroidal neovascularization by fluorescein angiography at the time of RPE tear formation. Of the four fellow eyes with neovascular macular degeneration and no dome-shaped PED, two of these eyes had active choroidal neovascularization and concurrent treatment with anti-VEGF therapy. All three eyes with dry age-related macular degeneration had mild to moderate disease without significant geographic atrophy and retained good visual acuity.

Four patients were treated with anti-VEGF therapy for wet macular degeneration prior to developing RPE tears, with an average of three pre-tear treatments of either bevacizumab (intra-vitreal 1.25 mg/0.05 ml) or ranibizumab (intra-vitreal 0.5 mg/0.05 ml) and range of 1-7 injections. One subject was found to have RPE tear formation four weeks following first treatment with intra-vitreal bevacizumab. In the remaining three subjects, RPE tear formation was the initial manifestation of their transformation to neovascular macular degeneration and these patients had no previous history of therapy for wet macular degeneration. No subjects had been treated with laser, including photodynamic therapy (PDT), in either eye.

Reliable measurements of choroidal thickness were attained in all of the images that were analyzed. Intergrader reproducibility was assessed by intraclass correlation coefficient, and the measurements by the two independent observers were found to be significantly identical. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) in mean choroidal thickness was between 0.907 and 0.997 in each area. The ICC was calculated to be 0.989 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.932–0.998) in the subfoveal region, 0.964 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.730–0.995) in the far nasal region, and 0.962 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.776–0.994) in the far temporal region.

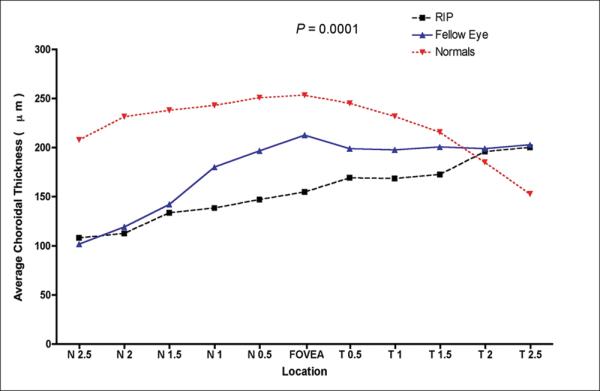

The mean choroidal thickness at each location was plotted (figure 2). Average subfoveal choroidal thickness in the eyes with the RPE tear was 154.9μm ± 10.1μm, and 212.9μm ± 10.6μm in those with intact RPE (p=0.035, figure 3). Moreover, in the eyes with RPE tear, the measured choroidal thickness was thickest temporally, thinner in the subfoveal region, and progressed to be thinnest nasally. In eyes with intact RPE, the measured choroidal thickness was greatest in the subfoveal region. In the far nasal region, the average choroidal thickness was measured to be 108.2μm ± 9.9μm in eyes with RPE tear and 101.8μm ± 7.4μm in those with intact RPE (p=0.05). In the far temporal region, the average choroidal thickness was 200.4μm ± 7.7μm in eyes with RPE tear and 203 μm ± 8.6μm in eyes with intact RPE (p=0.05).

Figure 2.

Graph of mean choroidal thickness in normal subjects and patients with RPE tear in one eye compared to the fellow eye at each of the 11 locations measured at 500 μm (0.5 mm) intervals temporal (T) and nasal (N). P-value represents the result of ANOVA.

Figure 3.

Graph of mean subfoveal choroidal thickness in patients with RPE tear in one eye compared to intact RPE in fellow eye.

The average age of normal subjects was 51.6 years (range 23-89). The average subfoveal, far nasal, and far temporal choroidal thickness measurements in normal subjects was found to be statistically greater compared to eyes with RPE tear and those with intact RPE (p > 0.05). The average subfoveal choroidal thickness in normal subjects was measured to be 256.8μm ± 75.8μm. In the far nasal and temporal regions, it was measured to be 243.2μm ± 69.3μm and 255.0μm ± 75.7μm, respectively.

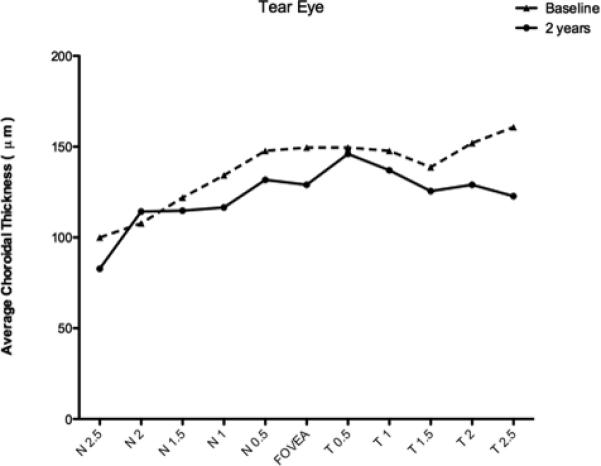

Longitudinal choroidal thickness data was available for eyes with RPE tear in four patients and for fellow, intact eyes in three patients. The average follow-up period was 29 months (range 25–36). There was no statistically significant difference between baseline choroidal thickness and follow-up measurements in tear and fellow eyes (p = 0.08). The mean choroidal thickness at baseline compared to follow-up in eyes with RPE tear was plotted (figure 4). There appeared to be a non-significant trend towards decreased choroidal thickness in all three locations (far nasal, subfoveal, far temporal) in tear eyes at follow-up. There was a non-significant trend towards decreased subfoveal choroidal thickness in eyes with tear compared to fellow eye with intact RPE. The average subfoveal choroidal thickness in the four eyes with the RPE tear was 129.0μm ± 17.7μm, and 212.9μm ± 10.6μm in those with intact RPE (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Graph of mean choroidal thickness in eyes with RPE tear at two year follow-up compared to baseline at each of the 11 locations measured at 500 μm (0.5 mm) intervals temporal (T) and nasal (N).

Discussion

RPE tears represent a potential severe complication of neovascular age-related macular degeneration which can lead to significant visual loss.19-20, 22 Our study detected a significant decrease in subfoveal choroidal thickness in subjects with RPE tear as compared with their fellow eye with intact RPE. Further, in comparison to normal eyes, those with RPE tear and fellow eyes with intact RPE had significant subfoveal thinning.

Subfoveal choroidal thinning may be a potential useful parameter in predicting risk of RPE tear in patients with PED associated with neovascular AMD in supplementation to other previously identified retinal OCT characteristics. One study described the formation of wavy RPE indentations or small interruptions and breaks in elevated RPE which was correlated with increased risk of developing an RPE tear in patients with pigment epithelium detachment following treatment with bevacizumab.24 Chiang et al found large PED basal diameter and vertical height to be correlated with increased risk of developing RPE tear following anti-VEGF therapy.54 Similarly, Chan et al measured preinjection vascularized PED height and found height > 400 μm to be a significant predictor for RPE tear formation following treatment with bevacizumab.56 Subfoveal choroidal thickness in addition to such retinal OCT parameters could help stratify risk of developing RPE tear and dictate treatment in patients with wet macular degeneration.

In our study, four out of seven patients were treated with anti-VEGF therapy prior to developing a RPE tear, with one patient developing the tear four weeks after the first treatment was given. It has been hypothesized that in addition to decreasing the vascular permeability and rate of growth of abnormal blood vessels in neovascular AMD, anti-VEGF therapies may also affect the choroidal vasculature and structure.46 Three patients had no previous history of anti-VEGF treatment and their choroidal thickness profiles did not significantly differ from those patients who had been treated. The choroidal thinning evident in these patients may be related to a process independent of an anti-VEGF mediated effect.

At present, it is unclear if this thinning of the choroid is a consequence of or precedes the RPE tear. Histopathology of AMD is characterized by attenuation of Bruch's membrane and degeneration of the choriocapillaris.45, 47 This suggests that there may be a component of choroidopathy in neovascular AMD. On fluorescein angiography, RPE tears do not typically exhibit leakage that may be expected in an exposed area of bare choroid and previous studies have suggested this may be secondary to concomitant atrophy of the choriocapillaris in the setting of AMD.19

The pathogenesis of RPE tear formation continues to remain controversial. Gass hypothesized that tears could occur due to rapid changes in vascular permeability which could induce sudden enlargement of the PED.26 Krishan et al described the role of tangential force produced by shrinking choroidal neovascular membrane.60 The role of contracting fibrovascular tissue was also illustrated by Spaide, who described reflective material suggestive of fibrovascular proliferation along the back surface of the RPE in PED by EDI OCT and subsequent contracture of the material following intravitreal ranibizumab.61 Our study detected significant subfoveal choroidal thinning in patients with RPE tear formation and this decrease persisted two years later. We hypothesize that choroidal thinning could be associated with contracting choroidal neovascular tissue leading to increased risk of RPE tear formation.

Further prospective studies could address the limitations present in our study. First, due to the rarity of RPE tear formation, the sample size of our study was limited to only seven patients. Further, since all study subjects had dome-shaped pigment epithelial detachments (PED) prior to developing RPE tear, the results of this study may not be applicable to eyes with different types of PED. Future studies are needed to address the choroidal thickness patterns in eyes with dome-shaped PED versus other different types of PED. Also due to the rarity of RPE tear formation and retrospective design of the study, SDOCT scans were not performed prior to RPE tear development in our patients. Additionally, the scan pattern used can only provide anatomic information. Choroidal thickness measurements taken with SDOCT have yet to be correlated with any functional parameter of the choroid. One such way of addressing this in the future would be to employ Doppler OCT.48-53 Another limitation is that there was not a standard protocol for initiation of therapy or the timing and number of injections.

In this investigation, we observed a significant decrease in subfoveal choroidal thickness in subjects with RPE tear as compared with their fellow eye with intact RPE. Subfoveal choroidal thinning may be a potential useful parameter in predicting risk of RPE tear in patients with PED, particularly if future studies can show choroidal thinning precedes the development of RPE tear formation.

Summary Statement.

This study was conducted to evaluate choroidal thickness with SDOCT in 7 eyes of 7 patients with neovascular AMD and RPE tear in one eye compared to fellow eye with intact RPE. There is a significant decrease in subfoveal choroidal thickness in subjects with RPE tear.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

This work was supported in part by a Research to Prevent Blindness Unrestricted grant to the New England Eye Center/Department of Ophthalmology -Tufts University School of Medicine, NIH contracts RO1-EY11289-23, R01-EY13178-07, R01-EY013516-07 and the Massachusetts Lions Eye Research Fund.

Footnotes

Financial Interest Disclosure

Jay S. Duker receives research support from Carl Zeiss Meditech, Inc. and Optovue, Inc.

None of the authors have a proprietary interest.

References

- 1.Huang D, Swanson EA, Lin CP, et al. Optical coherence tomography. Science. 1991;254(5035):1178–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1957169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spaide RF, Koizumi H, Pozzoni MC. Enhanced depth imaging spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(4):496–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imamura Y, Fujiwara T, Margolis R, Spaide RF. Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography of the choroid in central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 2009;29(10):1469–73. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181be0a83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujiwara T, Imamura Y, Margolis R, et al. Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography of the choroid in highly myopic eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(3):445–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spaide RF. Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography of retinal pigment epithelial detachment in age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147(4):644–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koizumi H, Yamagishi T, Yamazaki T, et al. Subfoveal choroidal thickness in typical age-related macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249(8):1123–8. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1620-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branchini L, Regatieri C, Adhi M, Flores-Moreno I, Manjunath V, Fujimoto J, Duker J. Analysis of choroidal thickness in patients with exudative (wet) age-related macular degeneration before and after treatment with intravitreal anti-VEGF agents using spectral domain optical coherence tomography. New England Eye Center; Boston: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manjunath V GJ, Fujimoto Duker JS. Choroidal thickness in patients with Age-Related Macular Denegeration Using Spectral Domain OCT. New England Eye Center; Boston: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torres VL, Brugnoni N, Kaiser PK, Singh AD. Optical Coherence Tomography Enhanced Depth Imaging of Choroidal Tumors. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(4):586–593. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maruko I, Iida T, Sugano Y, et al. Subfoveal Choroidal Thickness after Treatment of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease. Retina. 2011;151(4):594–603. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181eef053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manjunath V, Taha M, Fujimoto JG, Duker JS. Choroidal thickness in normal eyes measured using Cirrus HD optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150(3):325–9. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Branchini L, Adhi M, Regatieri CV, et al. Analysis of Choroidal Morphology and Vasculature in Healthy Eyes Using Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography. Ophthalmology. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.01.066. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoskin A, Bird AC, Sehmi K. Tears of detached retinal pigment epithelium. Br J Ophthalmol. 1981;65:417–422. doi: 10.1136/bjo.65.6.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsujikawa A, Hirami Y, Nakanishi H, et al. Retinal pigment epithelial tear in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Retina. 2007;27(7):832–8. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318150d864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yannuzzi LA, Guyer DR, Green WR. The Retina Atlas. Mosby; St. Louis: 1995. Central serous chorioretinopathy. pp. 262–277. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim JI, Lam S. A retinal pigment epithelium tear in a patient with angioid streaks. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;109:1672–1674. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070140026013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levin LA, Seddon JM, Topping T. Retinal pigment epithelial tears associated with trauma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112:396–400. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan A, Duker JS, Ko Th, et al. Ultra-high resolution optical coherence tomography of retinal pigment epithelial tear following blunt trauma. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2006;124(2):281–3. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.2.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Decker WL, Sanborn GE, Ridley M, et al. Retinal pigment epithelial tears. Ophthalmology. 1983;5:507–512. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(83)34534-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeo JH, Marcus S, Murphy RP. Retinal pigment epithelial tears. Patterns and prognosis. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coscas G, Koenig F, Soubrane G. The pretear characteristics of pigment epithelial detachments. A study of 40 eyes. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:1687–1693. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070140041025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gass JDM. Pathogenesis of tears of the retinal pigment epithelium. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68:513–519. doi: 10.1136/bjo.68.8.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chuang EL, Bird AC. Repair after tears of the retinal pigment epithelium. Eye. 1988;2:106–113. doi: 10.1038/eye.1988.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moroz I, Moisseiev J, Alhalel A. Optical coherence tomography predictors of retinal pigment epithelial tear following intravitreal bevacizumab injection. Ophthalmic Surgery, Lasers & Imaging. 2009;40(6):570–5. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20091030-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathews JP, Jalil A, Lavin MJ, Stanga PE. Retinal pigment epithelial tear following intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (Avastin): optical coherence tomography and fluorescein angiographic findings. Eye. 2007;21(7):1004–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gass JDM. Retinal pigment epithelial rip during krypton red laser photocoagulation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;98:700–706. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(84)90684-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gelisken F, Inhoffen W, Partsch M, et al. Retinal pigment epithelial tar after photodynamic therapy for choroidal neovascularization. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:518–520. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00813-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pece A, Introini U, Bottoni F, Brancato R. Acute retinal pigment epithelial tear after photodynamic therapy. Retina. 2001;21:661–665. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200112000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michels S, Aue A, Simader C, et al. Retinal pigment epithelium tears following verteporfin therapy combined with intravitreal triamcinolone. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:396–398. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dhalla MD, Blinder KJ, Tewari A, et al. Retinal epithelial pigment tear following intravitreal pegaptanib sodium. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:751–753. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh RP, Sears JE. Retinal pigment epithelial tears after pegaptanib injection for exudative age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:160–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyer CH, Mennel S, Schmidt JC, Kroll P. Acute retinal pigment epithelial tear following intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) injection for occult choroidal revascularization secondary to age related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:1207–1208. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.093732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicolo M, Ghiglione D, Calabria G. Retinal pigment epithelial tear following intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (Avastin). Eur J Ophthalmol. 2006;17:770–773. doi: 10.1177/112067210601600521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shah CP, Hsu J, Garg SJ, et al. Retinal pigment epithelial tear after intravitreal bevacizumab injection. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:1070–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carvounis PE, Kopel AC, Benz MS. Retinal pigment epithelium tears following ranibizumab for exudative age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:504–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bakri SJ, Kitzmann AS. Retinal pigment epithelial tear after intravitreal ranibizumab. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:505–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kitaya N, Nagaoka T, Hikichi T, et al. Features of abnormal choroidal circulation in central serous chorioretinopathy. Br J of Ophthalmol. 2003;87(6):709–712. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.6.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prunte C, Flammer J. Choroidal capillary and venous congestion in central serous chorioretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:26–34. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70531-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iida T, Kishi S, Hagimura N, et al. Persistent and bilateral choroidal vascular abnormalities in central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 1999;19:508–12. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199911000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inomata H, Minei M, Taniguchi Y, et al. Choroidal neovascularization in long standing case of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1983;27(1):9–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu W, Grunwald JE, Metelitsina TI, et al. Association of risk factors for choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration with decreased foveolar choroidal circulation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150(1):40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wakabayashi T, Ikuno Y. Choroidal filling delay in choroidal neovascularisation due to pathological myopia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(5):611–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.163535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baglio V, Gharbiya M, Balacco-Gabrieli C, et al. Choroidopathy in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus with or without nephropathy. J Nephrol. 2011;24(4):522–9. doi: 10.5301/JN.2011.6244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhutto I, Lutty G. Understanding age-related macular degeneration (AMD): Relationships between the photoreceptor/retinal pigment epithelium/Bruch's membrane/choriocapillaris complex. Mol Aspects Med. 2012;33(4):295–317. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lutty G, Grunwald J, Majji AB, et al. Changes in choriocapillaris and retinal pigment epithelium in age-related macular degeneration. Mol Vis. 1999;5:35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saint-Geniez M, Kurihara T, Sekiyama E, et al. An essential role for RPE-derived soluble VEGF in the maintenance of the choriocapillaris. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(44):18751–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905010106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coleman HR, Chan CC, Ferris FL, et al. Age-related macular degeneration. Lancet. 2008;372(9652):1835–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61759-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Makita S, Hong Y, Yamanari M, et al. Optical coherence angiography. Opt Express. 2006;14(17):7821–40. doi: 10.1364/oe.14.007821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miura M, Makita S, Iwasaki T, Yasuno Y. Three-dimensional visualization of ocular vascular pathology by optical coherence angiography in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(5):2689–95. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.White B, Pierce M, Nassif N, et al. In vivo dynamic human retinal blood flow imaging using ultra-high-speed spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Opt Express. 2003;11(25):3490–7. doi: 10.1364/oe.11.003490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Izatt JA, Kulkarni MD, Yazdanfar S, et al. In vivo bidirectional color Doppler flow imaging of picoliter blood volumes using optical coherence tomography. Opt Lett. 1997;22(18):1439–41. doi: 10.1364/ol.22.001439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Y, Lu A, Gil-Flamer J, et al. Measurement of total blood flow in the normal human retina using Doppler Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(5):634–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.150276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choi W, Baumann B, Liu JJ, et al. Measurement of pulsatile total blood flow in the human and rat retina with ultrahigh speed spectral/Fourier domain OCT. Biomed Opt Express. 2012;3(5):1047–61. doi: 10.1364/BOE.3.001047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chiang A, Chang LK, Yu F, et al. Predictors of anti-VEGF-associated retinal pigment epithelial tear using FA and OCT analysis. Retina. 2008;28(9):1265–9. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31817d5d03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chan CK, Meyer CH, Gross JG, et al. Retinal pigment epithelial tears after intravitreal bevacizumab injection for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2007;27:541–551. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3180cc2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chan CK, Abraham P, Meyer CH, et al. Optical coherence tomography measured pigment epithelial detachment height as a predictor for retinal pigment epithelial tears associated with intravitreal bevacizumab injections. Retina. 2010;30:203–211. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181babda5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chuang LK, Sarraf D. Tears of the retina pigment epithelium: an old problem in a new era. Retina. 2007;27:523–534. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3180a032db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Branchini L, Adhi M, Regatieri CV, et al. Analysis of Choroidal Morphology and Vasculature in Healthy Eyes Using Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography. Ophthalmology. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.01.066. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spaide R. Age-related choroidal atrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:801–810. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krishan NR, Chandra SR, Stevens TS. Diagnosis and pathogenesis of retinal pigment epithelium tears. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;100:698–707. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(85)90626-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spaide R. Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography of retinal pigment epithelial detachment in age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:644–652. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]