Abstract

Background

We examined levels of hyaluronan, a matrix glycosaminoglycan and versican, a matrix proteoglycan, in the sputum of asthmatics treated with mepolizumab (anti-IL-5 mAb) versus placebo to evaluate the utility of these measurements as possible biomarkers of asthma control and airway remodeling.

Methods

Severe, prednisone-dependent asthmatics received either mepolizumab or placebo as described in a previously published randomized, double blind, placebo controlled study. We measured hyaluronan and versican levels by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in sputum collected before and after the 16-week treatment phase. Patients underwent a predefined prednisone tapering schedule if they remained exacerbation free and sputum eosinophil percentage, asthma control questionnaire (ACQ) and spirometry were monitored.

Results

After 6 months of mepolizumab therapy and prednisone tapering there was a significant increase in sputum hyaluronan in the placebo group compared with baseline (P=0.003). In contrast, there was a significant decrease in sputum hyaluronan in the active treatment group compared with placebo (P=0.007) which correlated with improvements in FEV1% (P=0.001) and ACQ scores (P=0.009) as well as a decrease in sputum eosinophils (P=0.02). There was a non-significant increase in sputum versican in the placebo group (P=0.16), a decrease in the mepolizumab group (P=0.13) and a significant inverse correlation between versican reduction and FEV1% improvement (P=0.03).

Conclusions

Sputum hyaluronan values are reduced with mepolizumab therapy and correlate with improved clinical and spirometry values suggesting this measurement may serve as a non-invasive biomarker of asthma control.

Introduction

Airway remodeling involves the deposition of increased extracellular matrix (ECM) components and these structural changes are thought to play a role in the pathogenesis of asthma, contributing to the airway obstruction and functional lung impairments that are the hallmark of the disease. Substantial evidence indicates that asthmatics that develop airway remodeling have increased deposition of collagens, hyaluronan and proteoglycans [1–3].

Hyaluronan and versican are two components of the lung ECM involved in airway remodeling. Hyaluronan is an anionic, non-sulfated glycosaminoglycan that is found in all tissues and body fluids of vertebrates [4]. Hyaluronan acts as a vital structural component in connective tissues that allows for cell migration, immune cell adhesion, activation and intracellular signaling [5]. It binds inflammatory cells through cluster of differentiation 44 (CD44) and is therefore thought to play a key role in the inflammatory response [6]. In addition, synthesis of hyaluronan is enhanced in response to proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) [7, 8]. The levels of hyaluronan in sputum are significantly elevated in patients with asthma compared with atopic, non-asthmatics and in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in comparison to controls [9, 10].

Versican belongs to the family of hyaluronan-binding proteoglycans that are components of the ECM in a variety of soft tissues, including the lungs [11, 12]. In pulmonary tissue, versican deposition in the subepithelial layer is significantly increased in asthmatics compared with controls and inversely related to airway responsiveness [13]. Levels of veriscan in brochoalveolar lavage (BAL) have been reported to be increased in patients with mild asthma and to correlate with increased numbers of eosinophils and activated fibroblasts [14].

The role of eosinophils in airway remodeling and deposition of ECM is not clearly known. Decreases in airway and skin eosinophil numbers in response to mepolizumab treatment are reported to correlate with decreases in ECM proteins [15, 16]. A recent clinical trial in patients with severe asthma and sputum eosinophilia showed that treatment with mepolizumab had a significant prednisone-sparing effect that was associated with decreases in blood and sputum eosinophils, a decrease in asthma exacerbations and an improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) [17]. The objectives of this study were to evaluate levels of hyaluronan and versican in sputa from patients who participated in the mepolizumab study and to determine if these components of the ECM changed with treatment as well as correlate these findings with clinical data, pulmonary function and sputum esoinophil percentage (Eos%).

METHODS

Patients

Adult patients with asthma who required treatment with oral prednisone in addition to high dose inhaled corticosteroids to control symptoms and still had persistent sputum eosinophilia (>3%) were recruited from the clinics of the Firestone Institute for Respiratory Health in Hamilton, Ontario. Patient characteristics have been previously reported and are also presented in Table 1 [17].

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| Patient demographics | Mepolizumab | Placebo |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 7 | 10 |

| Age | 57.1 ± 11.3 | 59.5 ± 6.5 |

| Height | 169.7 ± 14.7 | 167.9 ± 10.2 |

| Weight | 87.8 ± 18.6 | 90.7 ± 15.3 |

| Number of Males | 4 | 7 |

| FEV1% | 62.85 ± 18.1 | 69.9 ± 17.3 |

| FEV1/FVC | 62 ± 17.4 | 65.9 ± 13.2 |

| Sputum Eos% | 21.1 ± 17.4 | 6.6 ± 9.6† |

| ACQ | 1.6 ± 0.74 | 1.9 ± 0.87* |

From 9 patients, one patient did not have ACQ data.

P=0.02. There was not significant differences in any other variables tested.

Study Design

As previously described [17], patients were randomly assigned to treatment with either mepolizumab 750 mg or placebo (normal saline diluent). According to a predefined reduction schedule, after the second infusion of the drug, prednisone was reduced by 5 mg at weeks 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22 if the patient had not had an exacerbation. Spirometry was performed and sputum samples were analyzed for differential cell counts. The Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) was used to quantify asthma control. This is a 7-item questionnaire with scores ranging between 0 (well controlled) and 6 (extremely poorly controlled). Table II provides ACQ scores, absolute FEV1, FEV1%, FEV1/VC ratio values, prednisone dose and sputum Eos% for all patients at the beginning and end of the study protocol.

Table 2.

Pre and Post Study Data

| Pre-Treatment | Post-Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mepolizumab | Placebo | Mepolizumab | Placebo | |

| FEV1 | 2.14 ± 1.05 | 2.22 ± 0.84 | 2.44 ± 1.11† | 2.07 ±0.84 |

| FEV1% | 62.85 ± 18.11 | 69.9 ± 17.29 | 72.71 ± 17.59† | 61.82 ± 20.27 |

| FEV1/FVC | 62 ± 17.39 | 65.91 ± 13.20 | 66.71 ± 12.92 | 63.36 ± 15.72 |

| Sputum Eos% | 21.1 ± 17.4 | 6.6 ± 9.6†¶ | 2.5 ± 4.0† | 28.4 ± 25.1‡§ |

| ACQ | 1.9 ± 0.87 | 1.9 ± 0.74* | 1.07 ± 0.64† | 2.41 ± 0.98*§ |

| Prednisone dose | 12.9 ±0.87 | 10.7 ± 5.3 | 3.6 ± 2.8 | 6.4 ± 5.5 |

Data from 9 patients, one patient did not have ACQ data.

= P=<0.05 Significant difference between pre-treatment and post treatment in mepolizumab group.

=P=<0.05 Significant difference between pre-treatment and post-treatment in placebo group.

=P=<0.05 Significant difference in pre-treatment Eos% between mepolizumab and placebo group.

=P=<0.05 Significant difference in post-treatment levels between the mepolizumab and placebo.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcomes of this study were the changes in hyaluronan and versican levels in sputum supernatants both within and between treatment groups. Secondary outcomes included correlations between changes in sputum measurements and change in FEV1%, ACQ scores and sputum Eos% over the study period.

Hyaluronan and Versican Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

A competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to detect hyaluronan and versican concentrations in the sputum samples. Since the addition of dithiothreitol (DTT) is a necessary step in the eosinophil isolation protocol, all sputum samples were first extensively dialyzed against phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to remove this reducing agent.

Hyaluronan assay

Sputum aliquots were digested with pronase (300 mg/ml) in 0.5 M Tris (pH 6.5) for 18 hours at 37°C after which, the pronase was inactivated by heating to 100°C for 20 minutes. We used a modification [18] of a previously described [19] competitive ELISA in which the samples to be assayed were first mixed with biotinylated hyaluronan binding protein (bHABP), the N-terminal hyaluronan-binding region of aggrecan. They were then added to hyaluronan-coated microtiter plates, with the final signal being inversely proportional to the level of hyaluronan added to the bHABP.

Versican assay

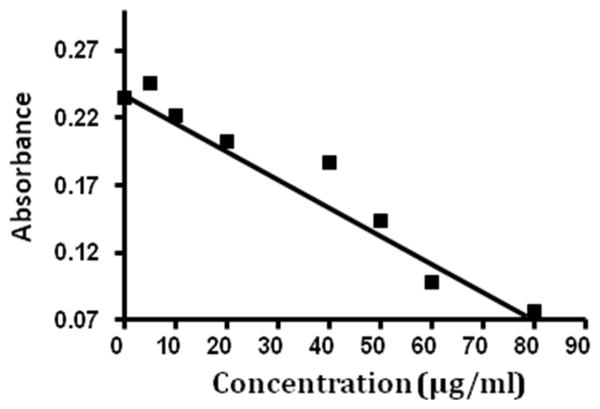

In order to measure versican levels in sputum, we developed a competitive ELISA, similar to the hyaluronan assay. Versican contains several disulfide bonds in its N-terminal region, so epitopes in that part of the molecule are denatured by reducing agents and do not properly refold following dialysis. Consequently, we used a single monoclonal antibody to the C-terminal end of the molecule, 2-B-1 (Seikagaku Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Versican standards or sputum samples were mixed with a limiting amount of 2-B-1 and incubated for one hour. This mixture was then added to a Nunc Maxisorp 96 well plate to which an excess of human versican was previously bound. To obtain human versican for use in the assay as a standard and to coat the wells, we used conditioned medium from human arterial smooth muscle cells and human leiomyosarcoma cells [20]. Free antibody subsequently bound to versican on the plate while antibody bound to any versican in the sputum samples was washed away, so that the final signal from the primary antibody was inversely proportional to the amount of versican in the sputum sample. Antibody bound to the plate was then incubated with biotinylated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Vector labs, Burlingame, CA) followed by incubation with peroxidase-linked-streptavidin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Streptavidin containing wells were incubated with peroxidase substrate consisting of peroxide and 2,2 azinobis (3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulfonic acid in sodium citrate buffer, pH 4.2) emitting a green colored product at OD405. This method produced a standard curve in which the colored signal was inversely related to the amount of versican in the sample in a linear fashion. The versican ELISA gave a linear response when run with standards in the range of from 0 μg/ml to 80 μg/ml (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

This representative standard curve was developed using known versican concentrations within the range of 0–80 μg/ml; y=0.234 +−0.002(x).

Statistical Analysis

Patient baseline characteristics as well as pre and post study data on FEV1, FEV1%, FEV1/FVC, sputum Eos%, ACQ and prednisone dose were published previously and are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 using means, standard deviations, and proportions [17]. Baseline differences between study groups were evaluated using independent t-tests for continuous measures and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. Within-group comparisons of hyaluronan and versican levels were performed using paired t-tests. Associations between baseline to post-treatment changes in biomarker levels (hyaluronan and versican) were adjusted for baseline values. All t-tests were two-sided and a p-value cutoff of 0.05 was used to denote statistical significance. The associations between baseline to post-treatment changes in biomarker levels and change in FEV1%, ACQ and Eos % were evaluated using Spearman’s correlation coefficients. Analyses were performed with the use of GraphPad Prism software (version 4.03; GraphPadSoftware Inc. LaJolla, CA).

RESULTS

Sputum Hyaluronan

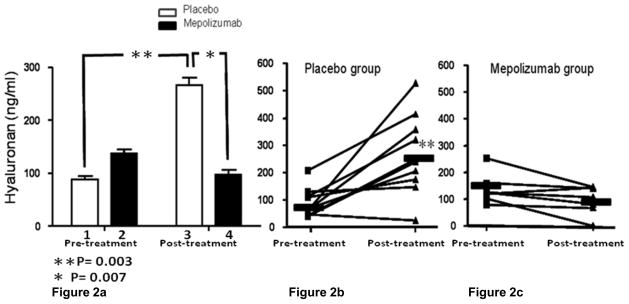

We evaluated a total of 17 patients, 7 treated with mepolizumab and 10 treated with placebo. There was no significant difference in pre-treatment sputum hyaluronan levels between the placebo and mepolizumab treatment groups (P=0.09; Fig 2a, bars 1 and 2). In contrast, after the treatment period, there was significantly more hyaluronan in the sputa of the placebo treated group compared to the mepolizumab treated group (P=0.007; Fig 2a, bars 3 and 4). Further, over the treatment period, there was a significant increase in mean sputum hyaluronan in the placebo treatment group (P= 0.003; Fig 2a, bars 1 and 3) and a numerical but non-significant decrease in sputum hyaluronan in the mepolizumab treated group (P= 0.08; Fig 2a, bars 2 and 4). Fig 2b and 2c display the sputum hyaluronan values for each subject before and after treatment with either placebo or mepolizumab.

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Mean sputum hyaluronan concentrations in placebo and mepolizumab treated patients before and at the end of the treatment period. There was no significant difference in mean sputum hyaluronan between groups before treatment (mepolizumab= 136.50 ± SE= 21.44 ng/ml vs. placebo= 88.48 ± SE= 16.68 ng/ml; P=0.09). From the beginning to the end of the treatment period there was a significant increase in mean sputum hyaluronan in the placebo group (pre-treatment= 88.48 ± SE= 16.68 ng/ml vs. post-treatment= 266.60 ± SE=45.51 ng/ml; P= 0.003). There was significantly more post-treatment sputum hyaluronan in the placebo specimens compared to the mepolizumab specimens (mepolizumab= 97.73 ± SE=20.18 ng/ml vs. placebo= 266.60 ± SE=45.51 ng/ml; P=0.007). There was a numerical but non-significant decrease in sputum hyaluronan in the mepolizumab treated group (pre-treatment= 136.50 ± SE= 21.44 ng/m vs. post-treatment = 97.73 ± SE= 20.18; P= 0.08).

Figure 2b and 2c- show individual patient sputum hyaluronan values in the placebo and mepoliuzumab treated groups pre and post treatment.

Sputum Versican

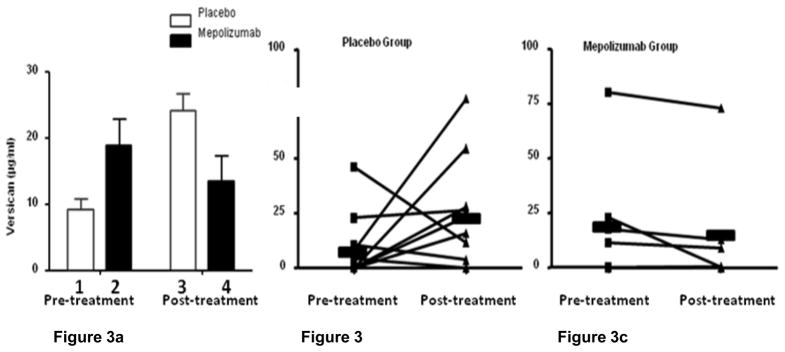

Versican levels in patient sputa ranged from 0 to 80 μg/ml and this was significantly greater than the levels of hyaluronan which did not exceed 600 ng/ml. Versican levels did not differ statistically between the mepolizumab and placebo treatment groups either before (P=0.38; Fig 3a, bars 1 and 2) or after treatment (P=0.19; Fig 3a, bars 3 and 4). From the beginning to the end of the treatment period there was a numerical increase in mean sputum versican concentration in the placebo treated patients (P= 0.16; Fig 3a, bars 1 and 3) and a numerical decrease in the concentration of this proteoglycan in the sputum of the patients treated with mepolizumab (P=0.13; Fig 3a, bars 2 and 4). However, neither of these changes reached statistical significance. Fig 3b and 3c display the individual sputum versican values for each patient before and after treatment with placebo or mepolizumab respectively.

Figure 3.

Figure 3a. Mean sputum versican concentrations in placebo and mepolizumab treated patients before and at the end of the treatment period. There was no significant difference in mean sputum versican levels before (Fig 3a, bars 1 and 2; mepolizumab= 18.83 ± SE 10.80 μg/ml vs. placebo= 9.27 ± SE 4.75 μg/ml; P=0.38) or after treatment (Fig 3a, bars 3 and 4; mepolizumab= 13.51 ± SE 10.12 μg/ml vs. placebo= 24.17 ± SE 7.89 μg/ml, P=0.19). From the beginning to the end of the treatment period there was not a significant difference in mean sputum versican concentration in the placebo treated patients (Fig 3a, bars 1 and 3; pre-treatment= 9.27 ± SE 4.75 μg/ml vs. post-treatment= 24.17 ± 24.95 μg/ml; P= 0.16) or the mepolizumab group (Fig 3a bars 2 and 4; pre-treatment= 18.83 ± SE 10.81 μg/ml vs. post-treatment= 13.51 ± SE 10.12 μg/ml; P=0.13).

Figure 3b and 3c show individual patient sputum versican values in the placebo and mepoliuzumab treated groups pre and post treatment.

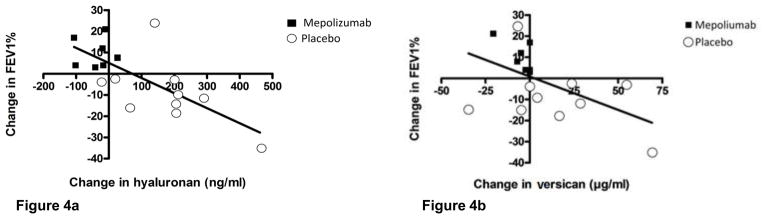

Sputum Hyaluronan and Versican versus change in FEV1%

Analysis of the change in sputum hyaluronan versus the change in FEV1% over the study period showed a significant inverse relationship between sputum hyaluronan concentration and FEV1% indicating that FEV1% values decreased when levels of sputum hyaluronan increased (P= 0.006; Fig 4a). Similarly, there was a significant inverse correlation between the change in sputum versican and the change in FEV1% (P= 0.03; Fig 4b).

Figure 4.

Figure 4a. Linear regression showing a significant inverse relationship between change in sputum hyaluronan concentration and change in FEV1% between the beginning and end of the study (P= 0.006).

Figure 4b- Similar analysis showing a significant inverse relationship between change in sputum vesican concentration and change in FEV1% (P=0.03).

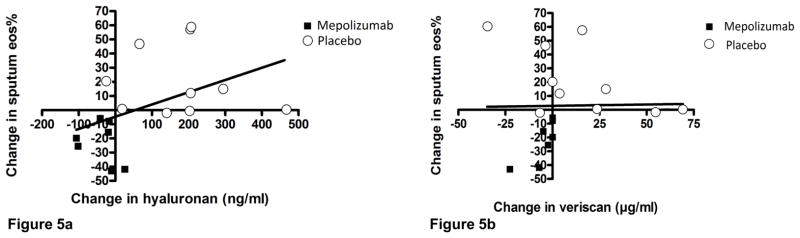

Sputum Hyaluronan and Versican versus change in Sputum Eos%

A comparison of the change in sputum hyaluronan versus the change in sputum Eos% demonstrated a significant correlation (P= 0.02; Fig 5a). There was no correlation between sputum Eos% and sputum versican (P= 0.23; Fig 5b).

Figure 5.

Figure 5a. Linear regression showing change in sputum hyaluronan concentration and change in sputum Eos% over the course of the study (P= 0.02).

Figure 5b- Similar analysis of relationship between change in sputum versican and change in sputum Eos% (P= 0.23).

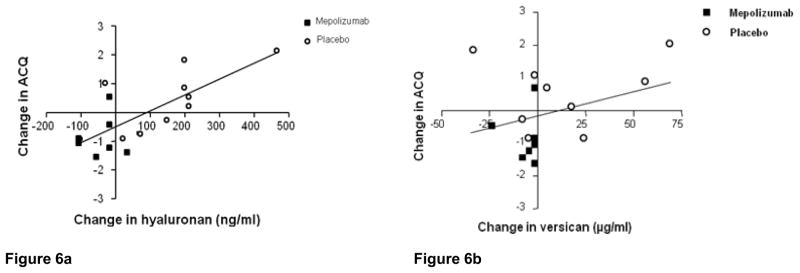

Sputum Hyaluronan and Versican versus change in ACQ

Analysis of the change in sputum hyaluronan versus the change in the ACQ revealed a positive correlation in the hyaluronan group indicating that as hyaluronan levels increased, so did ACQ scores (p= 0.009; Fig 6a). Of note, one subject in the placebo group did not have ACQ data recorded, thus only 9 subjects were included in the analysis. There was not a significant correlation between the change in sputum versican and change in ACQ scores (P=0.27; Fig 6b). As previously discussed, lower ACQ scores indicate improved asthma control.

Figure 6.

Figure 6a. Linear regression showing change in sputum hyaluronan concentration and change in ACQ over the course of the study (P= 0.009). Of note, only 9 of 10 subjects were included in this analysis because one subject did not have ACQ data documented.

Figure 6b- Similar analysis of relationship between change in sputum versican and change in ACQ over the course of the study which was not significant (P= 0.273).

DISCUSSION

This study reports several novel observations. First, a decrease in sputum hyaluronan correlated with improvements in FEV1% and ACQ scores suggesting that hyaluronan may be a useful biomarker of asthma control. Second, there was a direct correlation between the change in sputum eosinophils and hyaluronan suggesting there may be a link between the two. Finally, treatment with mepolizumab, an anti-IL5 mAb, was associated with a decrease in sputum hyaluronan compared to placebo suggesting that this treatment may lessen the amount of airway remodeling.

Airway remodeling is most directly measured by histologic analysis of lung biopsies, however for ethical and practical reasons, this is rarely done in clinical practice or even in most research protocols. For these reasons it was not done in the current study, but work by Rasmussen [21] et al suggests that the patients we studied had pathologic changes consistent with remodeling and that mepolizumab treatment lessened these changes. These investigators performed a long-term epidemiologic study which validated the postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio as an indirect indicator of airway remodeling and their data demonstrated that failure to achieve a normal ratio despite bronchodilator treatment is due to structural changes in the airway. As shown in Table II, all the patients in this study had severe asthma and a low FEV1/FVC ratio which is suggestive of airways remodeling. The increase in mean FEV1/FVC ratio at the end of the study in the mepolizumab treatment group in parallel with the decrease in sputum hyaluronan suggests that this ECM component may be a measure of airway remodeling and that mepolizumab treatment has the potential to reverse this process.

This study documents improvements in lung function and reductions in airway eosinophil accumulation and sputum hyaluronan in patients treated with mepolizumab. The data also shows a significant increase in sputum hyaluronan in the placebo group from the beginning to the end of the study. The increase in sputum hyaluronan was likely in part due to the concurrent prednisone taper in these patients in the absence of mepolizumab therapy. While the mechanism linking eosinophils, hyaluronan and airway obstruction is not fully understood, this study suggests that mepolizumab treatment might reduce airway remodeling and that measuring sputum hyaluronan may be a marker of this process.

It is believed that the airflow obstruction in asthmatic patients is in part due to an increase in ECM deposition. In patients with persistent asthma, Vignola et al reported an association between asthma symptoms, persistent airflow obstruction, eosinophils and hyaluronan in BAL, however a mechanistic link was not well defined [22]. These investigators also showed that an increase in sputum hyaluronan was correlated with a increase in ACQ, or worsened asthma control suggesting that there was increased airway inflammation and possibly remodeling in poorly controlled asthma patients.

There are multiple possible mechanisms by which eosinophils could affect the deposition of hyaluronan and thus airflow obstruction. Eosinophils may affect lung remodeling by regulating fibroblasts. It is known that fibroblasts play a key role in the remodeling process by producing collagen and elastin fibers as well as proteoglycans and glycoproteins [23]. It has also been shown that airway fibroblasts from asthmatics produce significantly increased concentrations of hyaluronan and hyaluronan synthase compared to controls [24]. Eosinophils secrete numerous cytokines which include IL-1β, TNF-α, tumor growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and endothelial growth factor (EGF) and these mediators are known to be potent stimulators of hyaluronan synthesis in lung fibroblasts and may contribute to the deposition of hyaluronan in the airways of eosinophilic asthmatics [25–29]. In addition, eosinophils express CD44 which binds hyaluronan and this interaction has been implicated in aggregation, proliferation and migration of this class of leukocytes [30, 31]. Further, eosinophils from allergic donors have higher levels of CD44 expression and develop hyaluronan binding ability in response to IL-5 and other cytokines [33, 33]. Anti-IL-5 treatment has been shown to decrease airway eosinophils as well as the deposition of the ECM proteins tenascin, lumican, and procollagen III [34]. Therefore, it is possible that asthma patients express a pathologic feedback loop where eosinophils stimulate fibroblast synthesis of hyaluronan through release of cytokines IL-1β, TGF-β and TNF-α and increase recruitment of additional eosinophils through up-regulation of CD44. Future studies are necessary to evaluate the role of eosinophils and hyaluronan production in asthma. Specifically, ex-vivo studies need to be designed which examine the effect of IL-5 on hyaluronan and versican localization in the pericellular matrix.

It is also clear that eosinophils interact with many other cells to enhance airway remodeling. Eosinophils generate chemokines that increase recruitment of effector T cells which can mediate airway remodeling. Jacobsen et al showed in mice devoid of eosinophils, that transfer of T-helper cell type 2 (Th2) polarized effector cells alone did not affect airway remodeling. However transfer of both Th2 polarized effector cells and eosinophils resulted in an increase in Th2 cytokines IL-5 and IL-13 in BAL and Th2 histopathology, defined as peribronchial aggregation of eosinophils, goblet cell metaplasia and airway epithelial cell mucin accumulation [35].

Finally, it is also possible that the amount of airway remodeling is independent of the number of eosinophils present in sputum. It was recently shown that repeated bronchoconstriction with either allergen or methacholine challenge resulted in a similar increase in collagen band thickness and mucous gland staining that was independent of eosinophil recruitment into the airways [36]. These authors conclude that airway remodeling can result from bronchoconstriction, independent of inflammation. Thus, it is possible that the mechanism by which sputum hyaluronan was decreased in the mepolizumab treated group was the result of improved pulmonary function and reduced exacerbations of bronchospasm.

The measurement of sputum versican may be an overestimation of the total mass of versican in our sample. In the ELISA that we developed to measure versican in our sputum samples, we used an antibody specific for the C-terminal portion while our standard curve used intact versican that measured the mass in the range of 0–80 μg/ml. All forms of versican share the carboxy-terminal G3 domain which is identified by our versican ELISA, however, the versican levels measured in sputum samples may represent C-terminal versican fragments. C-terminal fragments are the molar equivalent of intact versican molecules used in the standard but possess a lower mass. Moreover, C-terminal fragments of versican have been shown to exist in human plasma and may serve an immune function. Human leukocytes express P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) which promotes leukocyte recruitment by binding to selectins and also to the C-terminus of versican, thus promoting leukocyte aggregation [37]. The recruited leukocytes then produce matrix metalloproteinases which cleave versican and release versican fragments, producing a positive feedback loop [38]. While it is unclear whether we are measuring intact versican or verican fragments, our results suggest that versican accumulates in sputum and may be involved in leukocyte recruitment and aggregation.

In summary, we report that hyaluronan and versican can be measured in sputum supernatants and that hyaluronan decreased following treatment with mepolizumab and this correlated with the improvement in FEV1% and ACQ scores. Given this data we believe that sputum hyaluronan and possibly versican may be early, sensitive biomarkers of asthma control and possibly airway remodeling in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. We also showed that there is a direct correlation between the change in sputum Eos% and hyaluronan and we propose that the two are linked and that further studies are needed to evaluate the mechanism of IL-5 on hyaluronan production.

Acknowledgments

Dr Nair is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Airway Inflammometry. The clinical trial was funded by an unrestricted investigator-initiated grant from GlaxoSmithKline.

Abréviations

- ACQ

asthma control questionnaire

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- bHABP

biotinylated hyaluronan binding protein

- CD44

cluster of differentiation 44

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- eNO

exhaled nitric oxide

- Eos %

eosinophil percentage

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in 1 second

- IFN-γ

interferon-gamma

- IL-1β

interleukin-1 beta

- IL-5

interleukin-5

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PSGL-1

P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1

- TGF-β

tumor growth factor-beta

- Th2

T-helper cells type 2

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

References

- 1.Johnson PR, Burgess JK. Airway smooth muscle and fibroblasts in the pathogenesis of asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2004;4(2):102–8. doi: 10.1007/s11882-004-0054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parameswaran K, Willems-Widyastuti A, Alagappan VK, Radford K, Kranenburg AR, Sharma HS. Role of extracellular matrix and its regulators in human airway smooth muscle biology. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2006;44(1):139–46. doi: 10.1385/CBB:44:1:139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamauchi K, Inoue H. Airway remodeling in asthma and irreversible airflow limitation-ECM deposition in airway and possible therapy for remodeling- Allergol Int. 2007;56(4):321–9. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.R-07-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraser JR, Laurent TC, Laurent UB. Hyaluronan: its nature, distribution, function and turnover. J Intern Med. 1997;242(10):27–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Day AJ, Prestwich GD. Hyaluronan-binding proteins: tying up the giant. Biol Chem. 2002;277(7):4585–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeGrendele HC, Estess P, Seigelman MH. Requirement for CD44 in activated T cell extravasation in to an inflammatory site. Science. 1997;278(5338):672–5. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de la Motte CA, Hascall VC, Calabro A, Yen-Lieberman B, Strong SA. Mononuclear leukocytes preferentially bind via CD44 to hyaluronan on human intestinal mucosal smooth muscle cells after virus infection or treatment with poly(I. C) J Biol Chem. 1999;274(43):30747–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilkinson TS, Potter-Perigo S, Tsoi C, Altman LC, Wight TN. Pro- and anti-inflammatory factors cooperate to control hyaluronan synthesis in lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31(1):92–9. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0380OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tufvesson E, Aronsson D, Bjermer L. Cysteinyl-leukotriene levels in sputum differentiate asthma from rhinitis patients with or without bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37(7):1067–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dentener MA, Vernooy JH, Hendriks S, Wouters EF. Enhanced levels of hyaluronan in lungs of patients with COPD: relationship with lung function and local inflammation. Thorax. 2005;60(2):114–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.020842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wight TN. Versican: a versatile extracellular matrix proteoglycan in cell biology. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14(5):617–23. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00375-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Kluijver J, Schrumpf JA, Evertse CE, Sont JK, Roughley PJ, Rabe KF, Hiemstra PS, Mauad T, Sterk PJ. Bronchial matrix and inflammation respond to inhaled steroids despite ongoing allergen exposure in asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35(10):1361–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang J, Olivenstein R, Taha R, Hamid Q, Ludwig M. Enhanced proteoglycan deposition in the airway wall of atopic asthmatics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(2):725–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.9809040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larsen K, Tufvesson E, Malmström J, Mörgelin M, Wildt M, Andersson A, Lindstrom A, Malmstrom A, Lofdahl CG, Mark-Varga G, Bjermer L, Westergren-Thorsson G. Presence of activated mobile fibroblasts in bronchoalveolar lavage from patients with mild asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(10):1049–56. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-507OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flood-Page P, Menzies-Gow A, Phipps S, Ying S, Wangoo A, Ludwig MS, Barnes N, Robinson D, Kay AB. Anti-IL-5 treatment reduces deposition of ECM proteins in the bronchial subepithelial basement membrane of mild atopic asthmatics. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(7):1029–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI17974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang J, Torio A, Donoff RB, Gallagher GT, Egan R, Weller PF, Wong DT. Depletion of eosinophil infiltration by anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody (TRFK-5) accelerates open skin wound epithelial closure. Am J Pathol. 1997;151(3):813–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nair P, Pizzichini MM, Kjarsgaard M, Inman MD, Efthimiadis A, Pizzichini E, Hargreave FE, O’Byrne PM. Mepolizumab for prednisone-dependent asthma with sputum eosinophilia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(10):985–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkinson TS, Potter-Perigo S, Tsoi C, Altman LC, Wight TN. Pro- and anti-inflammatory factors cooperate to control hyaluronan synthesis in lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31:92–99. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0380OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Underhill CB, Nguyen HA, Shizari M, Culty M. CD44 positive macrophages take up hyaluronan during lung development. Dev Biol. 1993;155:324–336. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olin KL, Potter-Perigo S, Barrett PH, Wight TN, Chait A. Lipoprotein lipase enhances the binding of native and oxidized low density lipoproteins to versican and biglycan synthesized by cultured arterial smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(49):34629–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rassmussen Rasmussen F, Taylor DR, Flannery EM, Cowan JO, Greene JM, Herbison GP, Sears MR. Risk factors for airway remodeling in asthma manifested by a low postbronchodilator FEV1/vital capacity ratio: a longitudinal population study from childhood to adulthood. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(11):1480–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2108009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vignola AM, Chanez P, Campbell AM, Souques F, Lebel B, Enander I, Bousquet Airway inflammation in mild intermittent and in persistent asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(2):403–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.2.96-08040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheppard MN, Harrison NK. New perspectives on basic mechanisms in lung disease. 1. Lung injury, inflammatory mediators, and fibroblast activation in fibrosing alveolitis. Thorax. 1992;47(12):1064–74. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.12.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang J, Jiang D, Jung Y, Xie T, Ingram J, Church T, et al. Role of hyaluronan and hyaluronan-binding proteins in human asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(2):403–411. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi T, Kouzaki H, Kita H. Human eosinophils recognize endogenous danger signal crystalline uric acid and produce proinflammatory cytokines mediated by autocrine ATP. J Immunol. 2010;184(11):6350–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lacy P, Moqbel R. Eosinophil cytokines. Chem Immunol. 2000;76:134–55. doi: 10.1159/000058782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilkinson TS, Potter-Perigo S, Tsoi C, Altman LC, Wight TN. Pro- and anti-inflammatory factors cooperate to control hyaluronan synthesis in lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31(1):92–9. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0380OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papakonstantinou E, Roth M, Tamm M, Eickelberg O, Perruchoud AP, Karakiulakis G. Hypoxia differentially enhances the effects of transforming growth factor-beta isoforms on the synthesis and secretion of glycosaminoglycans by human lung fibroblasts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;301(3):830–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.3.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chow G, Tauler J, Mulshine JL. Cytokines and growth factors stimulate hyaluronan production: role of hyaluronan in epithelial to mesenchymal-like transition in non-small cell lung cancer. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:485468. doi: 10.1155/2010/485468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turley EA, Noble PW, Bourguignon LY. Signaling properties of hyaluronan receptors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(7):4589–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100038200. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsumoto K, Appiah-Pippim J, Schleimer RP, Bickel CA, Beck LA, Bochner BS. CD44 and CD69 represent different types of cell-surface activation markers for human eosinophils. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;18(6):860–6. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.18.6.3159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dallaire MJ, Ferland C, Lavigne S, Chakir J, Laviolette M. Migration through basement membrane modulates eosinophil expression of CD44. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32(6):898–905. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2002.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watanabe Y, Hashizume M, Kataoka S, Hamaguchi E, Morimoto N, Tsuru S, Katoh S, Miyake K, Matsushima K, Tominaga M, Kurashige T, Fujimoto S, Kincade PW, Tominaga A. Differentiation stages of eosinophils characterized by hyaluronic acid binding via CD44 and responsiveness to stimuli. DNA Cell Biol. 2001;20(4):189–202. doi: 10.1089/104454901750219071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flood-Page P, Menzies-Gow A, Phipps S, Ying S, Wangoo A, Ludwig MS, Barnes N, Robinson D, Kay AB. Anti-IL-5 treatment reduces deposition of ECM proteins in the bronchial subepithelial basement membrane of mild atopic asthmatics. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(7):1029–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI17974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacobsen EA, Ochkur SI, Pero RS, Taranova AG, Protheroe CA, Colbert DC, Lee NA, Lee JJ. Allergic pulmonary inflammation in mice is dependent on eosinophil-induced recruitment of effector T cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205(3):699–710. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grainge CL, Lau LC, Ward JA, Dulay V, Lahiff G, Wilson S, Holgate S, Davies DE, Howarth PH. Effect of bronchoconstriction on airway remodeling in asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(21):2006–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng PS, Vais D, Lapierre D, Liang YY, Lee V, Yang BL, Yang BB. PG-M/versican binds to P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 and mediates leukocyte aggregation. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 24):5887–95. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Halpert I, Sires UI, Roby JD, Potter-Perigo S, Wight TN, Shapiro SD, Welgus HG, Wickline SA, Parks WC. Matrilysin is expressed by lipid-laden macrophages at sites of potential rupture in atherosclerotic lesions and localizes to areas of versican deposition, a proteoglycan substrate for the enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93(18):9748–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]