Abstract

We use U2OS cells as in vivo ‘test tubes’ to study how the same cytoplasmic environment has opposite effects on the stability of two different proteins. Protein folding stability and kinetics were compared by Fast Relaxation Imaging (FReI), which combines a temperature jump with fluorescence microscopy of FRET-labeled proteins. While the stability of the cytoplasmic enzyme PGK increases in cells, the stability of the cell-surface antigen VlsE, which presumably did not evolve for stability inside cells, decreases. VlsE folding also slows down more than PGK folding, relative to their respective in aqueous buffer kinetics. Our FRET measurements provide evidence that VlsE is more compact inside cells than in aqueous buffer. Two kinetically distinct protein populations exist inside cells, making a connection with previous in vitro crowding studies. In addition, we confirm previous studies showing that VlsE is stabilized by 150 mg/ml of the carbohydrate crowder Ficoll, even though it is destabilized in the cytoplasm relative to aqueous buffer. We propose two mechanisms for the observed destabilization of VlsE in U2OS cells: long range interactions competing with crowding, or shape-dependent crowding, which favors more compact states inside the cell over the elongated aqueous buffer native state.

Keywords: Protein folding, extracellular protein, Variable major protein-like sequence Expressed (VlsE), Fast Relaxation Imaging (FReI), Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)

Introduction

Studies in aqueous buffer have revealed much about the folding and misfolding of isolated proteins,1 but the cell has also evolved many mechanisms that affect the folding process. For example, chaperones can bind proteins to perform a host of functions, such as storage and release of non-native proteins, or assistance with disassembly of aggregates.2; 3; 4 As in the test tube, proteins can unfold and refold many times inside the cell after their initial ribosomal synthesis. The interior of the cell provides a highly differentiated and crowded environment that can enhance refolding yield and that modulates protein stability and folding rates compared to in vitro.5; 6

Volume exclusion by crowding generally has a stabilizing effect on globular proteins because the folded state is more compact than the unfolded polypeptide chain, which is therefore entropically disfavored.7; 8; 9 A host of models and in vitro experiments have analyzed excluded volume effects: the shape and size of the proteins and crowding agents,10; 11; 12 ‘proteinaceous’ vs. ‘synthetic’ crowding agents,13; 14 and long range interactions15; 16; 17 all affect protein stability, folding kinetics and diffusion. Shape/size mismatch and long-range interactions can compete with the basic excluded volume effect. For example, a recent combined analysis of carbohydrate and proteinaceous crowders showed that both produce similar stability trends in crowded proteins. Above a certain crossover temperature, crowding acts to stabilize proteins, while below it proteins are destabilized. The two classes of crowders were distinguished by their crossover temperature, not by their general behavior.18

Much less is known about the crowding effect inside cells, although studies have begun to elucidate folding in cells during the past several years.5; 6; 19 Using amide hydrogen exchange detected by mass spectrometry, the monomeric λ repressor has about the same stability inside E. coli as in vitro.19 Via a FlAsH fluorescent probe, the cellular retinoic acid binding protein was destabilized inside E. coli in the presence of urea.6 A variant of the protein L that is ≈80% denatured in aqueous buffer was not able to refold inside the E. coli cytoplasm during NMR studies.20 In contrast, real-time imaging of FRET-labeled phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK-FRET) inside cells revealed various degrees of increased stability and folding speed in different organelles.21 Increased intracellular FRET of this protein also indicates a more compact folded state inside the cell, consistent with in vitro studies.22

In vitro folding studies have benefited greatly from a systematic comparison of the same protein in different environments, or different proteins in the same environment. The time has come for in-cell studies to do the same, either by changing the intracellular environment,21 or by comparing different proteins expressed in the same cell line. Here we do the latter, using U2OS cells as ‘in vivo test tubes’ to compare stability and folding of two different proteins. We specifically ask the question: Unlike PGK, which is an intracellular protein stabilized in U2OS cells, could an extracellular globular protein show the opposite trend in the cell? Our ideal extracellular protein would preferably be a two-state folder (to simplify kinetic analysis); of similar size, folding rate and stability as PGK (415 residues, ~1 s−1, 39 °C).

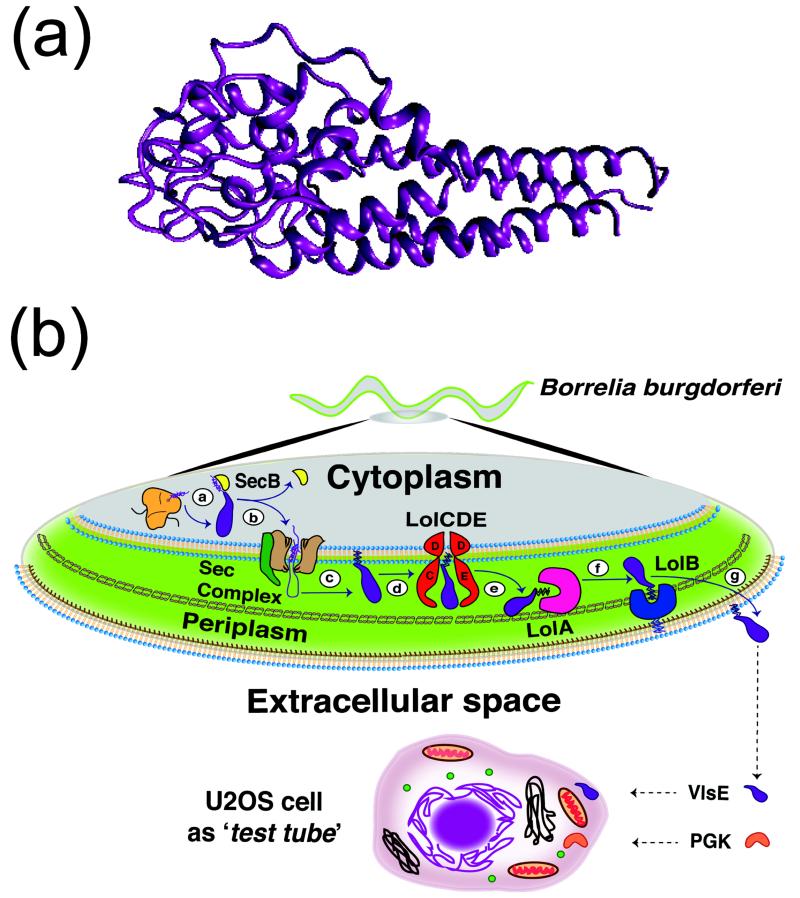

A truncation of Variable major protein-Like Sequence, Expressed (VlsE), whose folding was extensively studied by Wittung-Stafshede and coworkers,10 turns out to satisfy all of these requirements (Fig. 1a). At 341 residues, it is the largest kinetically characterized two-state folder with a folding relaxation rate of 5 ± 2 s−1,23 and a stability similar to PGK in vitro when both proteins are FRET-labeled for in-cell detection (see below). Truncated VlsE originates from a highly expressed cell surface protein of the Borrelia burgdorferi spirochete and is believed to be important during host invasion in Lyme disease.24 Unlike PGK, which is an important cytoplasmic metabolic enzyme, VlsE has to be unfolded and translocated to be displayed on the outer membrane (Fig. 1b). Although VlsE is stabilized by simple carbohydrate crowders,11 it seems unlikely that it evolved to be stabilized by the cytoplasm. Indeed, we find that VlsE is significantly destabilized in the U2OS cytoplasm, whereas PGK is significantly stabilized in the cell.

Figure 1. VlsE protein.

(a) VlsE crystal structure. (b) Simplified scheme of VlsE protein translocation across the Borrelia bugdolferi double membrane. ⓐ VlsE is synthesized by the ribosome and folds in the cytoplasm. ⓑ The molecular chaperone SecB recognizes the signal sequence in the N-terminal region of VlsE and transfers VlsE to the Sec machinery that translocates it inside the periplasmic space using ATP energy. ⓒ Phosphatidylglycerol/prolipoprotein diacylglyceryl transferase (Lgt), lipoprotein signal peptidase (LspA) and phospholipid/apolipoprotein transacylase (Lnt) process the lipoprotein precursor into a mature form. ⓓ The transporter LolCDE removes the lipoprotein from the inner membrane, and forms a hydrophilic complex with LolA. ⓔ The periplasmic molecular chaperone LolA removes the lipoprotein from LolCDE. ⓕ LolA transfers the lipoprotein to LolB. ⓖ The lipoprotein is incorporated into the outer membrane by LolB. For our experiments we truncated the lipidation signal sequence and transfected a DNA plasmid containing the VlsE gene into U2OS cells, where it remains in the cytoplasm after translation.

Besides comparing the stability and folding kinetics of two proteins for the first time in the same cellular environment, VlsE in-cells is also of interest for comparison with in vitro crowding experiments. In the presence of 100 mg/mL Ficoll, VlsE folds three times faster than in aqueous solution, and in the presence of 400 mg/ml it is stabilized by 6 °C 12 In contrast, our in-cell kinetics is slower, and the stability is lower than that found aqueous buffer. The stabilization found by crowding in vitro is consistent with simulations which predict an increase in helical content and a large change in shape (from elongated as in Fig. 1a to more compact bean and spherical shapes) in crowded environments.12 In partial agreement with these earlier results, our measurements reveal evidence for multiple VlsE states and greater compactness of the protein in-cell than in aqueous buffer, although these compact states may not be stabilized as much inside the cell as by the carbohydrate crowder Ficoll.

Results

Protein measurement conditions

Protein stability and kinetics inside cells were imaged using FRET. To allow a direct comparison with PGK-FRET results,5 the same fluorescent probes were incorporated into VlsE. We cloned the green fluorescence protein (AcGFP1) as donor “D” at the N-terminus and mCherry as acceptor “A” at the C-terminus. The donor-acceptor ratio D/A of this construct is larger in the unfolded state (greater end-to-end distance, less FRET) than in the folded state. For in vitro experiments in aqueous buffer or Ficoll buffer, the protein solution was placed inside an imaging chamber as described in the Methods section. In-cell experiments were performed on single U2OS cells, as in our previous PGK-FRET studies, after transfection of the plasmid that contained the VlsE-FRET gene. For equilibrium measurements, D and A fluorescence were imaged for 4 s. Then a 4° C temperature jump was applied to the sample for a kinetics measurement. After each equilibrium/kinetic measurement, the temperature was increased by a resistive element mounted on the stage for the next pair of measurements. 3 minutes of equilibration time were allowed between measurements, a protocol identical to the one used for PGK studies. The equilibrium temperature was monitored with a thermocouple, and temperature jumps (T-jumps) were calibrated using mCherry quantum yield as the temperature probe (Methods).21

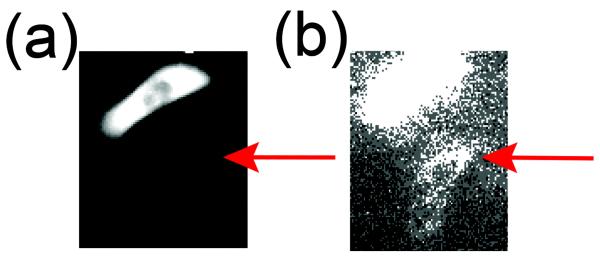

VlsE-FRET is dispersed in the cytoplasm and background fluorescence is negligible

The representative cell imaged in Fig. 2a shows that VlsE-FRET is dispersed throughout the cytoplasm despite its lowered stability. No localization or other sign of aggregation was observed in cells at temperatures below 45 °C. Fig. 2b shows the same view as 2a, with the pixel RGB values multiplied up by a factor of 20 to show background autofluorescence of an adjacent unlabeled cell. We did not observe auto-fluorescence > 2% of the combined GFP/mCherry signal in labeled cells with 470 nm LED excitation. Finally, we confirmed that measured melting temperatures, rates, and qualitative trends in D/A ratios are independent of instrument alignment (Supplemental Fig. S1), and that the previously reported temperature trends in AcGFP1 and mCherry quantum yields (decrease with temperture) still hold.21

Figure 2.

(a) Representative cell demonstrating uniform VlsE-FRET dispersion inside a U2OS cell. The darker area is the location of the cell nucleus, where the optical pathlength through the cytoplasm is shorter. (b) The same area with pixel values (brightness) multiplied by 20×. The original cell is saturated, and the red arrows indicate the position of a non-transfected cell that shows very low autofluorescence emission background (≈ 2% of the transfected cell).

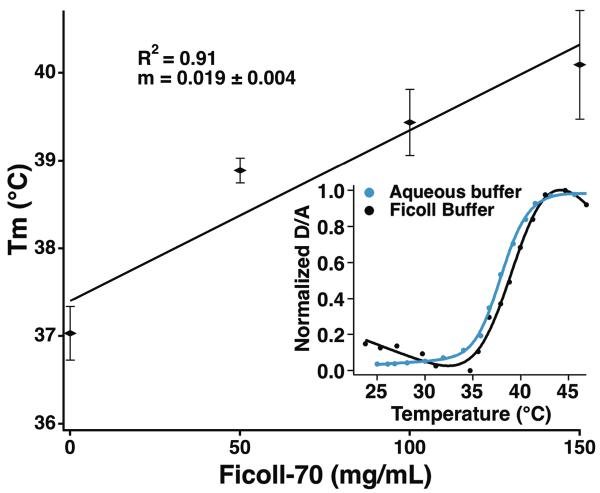

VlsE-FRET is stabilized in Ficoll

The thermodynamic measurements in Ficoll buffer by Homouz et al. showed that unlabeled VlsE is stabilized by a simple crowder in vitro,11 just as we found previously for PGK-FRET.22 We measured FRET-detected melting curves of our VlsE-FRET construct at different Ficoll concentrations ranging from 0 to 150 mg/mL (Fig. 3). The melting temperature of VlsE-FRET increases by about 3 °C between aqueous buffer and 150 mg/ml Ficoll buffer (Fig. 3 inset). This data agrees with Homouz et al results for VlsE in Ficoll buffer experiments in which they observed stabilization during urea titrations. Thus FRET-labeled VlsE behaves just like VlsE and PGK-FRET in a Ficoll buffer: its stability increases.

Figure 3.

Melting temperature Tm of VlsE-FRET vs. Ficoll-70 concentration (0 to 150 mg/ml) fitted to a line.

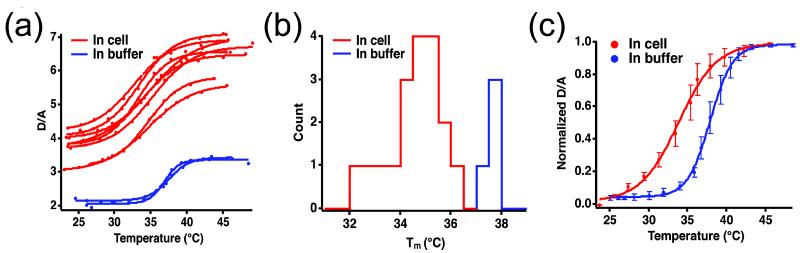

VlsE-FRET is destabilized inside cells

The Donor/Acceptor (D/A) ratio of VlsE-FRET increased with temperature, yielding sigmoid traces for all in vitro and in-cell equilibrium unfolding experiments (Fig. 4a; additional experiments in Fig. S1a). All thermal unfolding traces were fitted using a two-state free energy model whose fitting parameters are presented in SI Tables 1 and 2. The parameter Tm is the melting temperature of the protein, at which the free energy of the folded and unfolded states is equal. A comparison of in vitro and in-cell Tm demonstrates that the melting temperature of VlsE is on average 3 °C lower inside cells than in aqueous buffer (Figure 4c), and 6 °C lower than in 150 mg/ml Ficoll buffer (see Fig. 3 inset). Even though experiments with Ficoll buffer crowders have demonstrated stabilization of VlsE compared to aqueous buffer,11; 23 inside the cell the crowding effect is either compensated by longer range interactions, or modified by new structural ensembles, or both (see Discussion). Measurements on PGK-FRET done in parallel with the same detection geometry confirmed its stabilization of 3 °C relative to aqueous buffer reported previously.5 Thus PGK-FRET and VlsE-FRET are both stabilized by Ficoll buffer, but PGK-FRET is also stabilized in the cytoplasm, whereas VlSE-FRET is destabilized in the cytoplasm.

Figure 4.

(a) Temperature titration traces of D/A in cells (red) and in aqueous buffer (blue). (b) Histogram of melting temperatures in cells (red) and in aqueous buffer (blue). (c) Averaged traces of in cell (red) and in buffer (blue) experiments.

Figure 4b shows that the range of melting temperatures is greater in U2OS cells than in vitro, where the range is set by measurement error. No obvious thermodynamic signature of two distinct protein populations inside the cells is evident in Fig. 4b, although the number of cells studied is small, and better statistics may yet reveal a low-melting population. No overlap between in-cell and aqueous buffer experiment was found. Even the least de-stabilizing cells have a lower Tm than any of the in vitro measurements.

VlsE-FRET may change shape inside cells

It is evident from Fig. 4a that in-cell VlsE-FRET (red traces) consistently has a higher average D/A fluorescence intensity ratio (less FRET) than VlsE-FRET in vitro (see also supplementary figure 1a for more results). The opposite was observed for PGK-FRET, whose energy transfer between donor and acceptor was more efficient inside cells and crowded by Ficoll.

Homouz et al. have proposed an alternative native state for VlsE upon crowding,11 the bean-shaped B state, which is somewhat more compact than the very elongated native state N shown in Fig. 1a. Supplementary Fig. 5 shows their prediction for the N-C termini distance in the N and B states. The B state has a larger N-C distance despite its greater compactness, which would result in a larger D/A ratio (less energy transfer). Although our measurement of in-cell D-A distance does not provide any detailed shape information about the protein, it is consistent with an in-cell population of a state of greater N-C termini separation, such as the B state. If so, the distribution’s width from D/A ≈ 3 to ≈ 4.5 indicates a range of compactness in different cells, not a completely homogeneous structural state. It must be noted that their proposed in Ficoll buffer B state requires higher temperature to be stabilized (Fig. S5a), whereas we observe a population with larger D/A ratio even in room temperature cells (Fig. 4a). Thus the combination of crowding and long range effects would have to act significantly differently in the cell than in Ficoll buffer, which is already clear from the opposite trends we observe for VlsE-FRET in the cell (Fig. 4) and in Ficoll (Fig. 3).

Kinetics of VlsE-FRET slows down more than kinetics of PGK-FRET

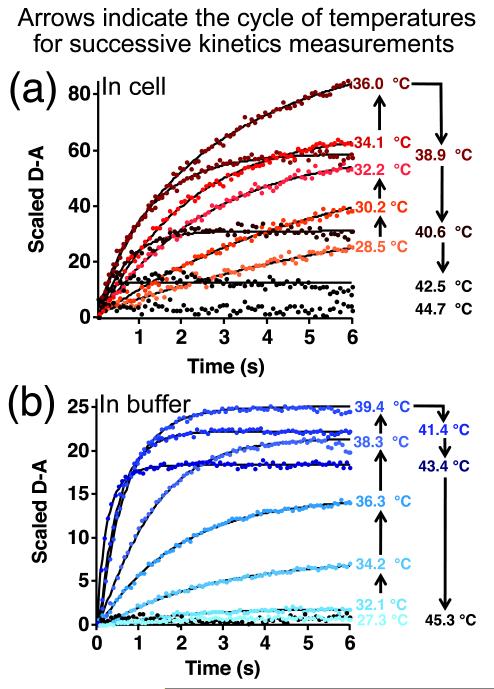

To compare the kinetics of VlsE-FRET folding aqueous buffer and in 8 cells, the scaled difference of D-A21 (D-A) as function of time was monitored after a 4 °C temperature jump (Fig. 5). The starting temperature of the jumps ranged from about 25 to 45 °C. The amplitude of the kinetic signal reached a maximum around Tm, where a temperature jump produces the largest population relaxation.25 In aqueous buffer, the maximum amplitude was reached at about 39.5 °C, and in U2OS cells on average at about 36.5 °C, both consistent with the Tm values from thermodynamics (the largest amplitude should be for a 4 °C jump from 2 °C below Tm to a final temperature of 2 °C above Tm).

Figure 5.

Sample kinetics traces. (a) in cells (red). (b) in aqueous buffer (blue). The colored temperatures indicate the temperature after the temperature jump, and black arrows indicate the cycle of temperatures at which successive kinetic data points were collected.

Our aqueous buffer result of kobs = 2.3 ± 0.4 s−1 (τ = 0.4 ± 0.1 s) at Tm is in reasonable agreement with the value of 5 ± 2 s−1 in ref. 23. Our value was obtained by fitting the data in Fig. 6a to a stretched exponential Aexp[-(kobst)β] to test for deviations from two-state behavior (Methods, Table 1 in SI). No significant deviations were found. The average β from four aqueous buffer measurements 0.96±0.02 is in agreement with the previous finding that VlsE is an apparent two-state folder.23 Therefore kobs is the two-state total relaxation rate, equal to the sum of forward and backward rate coefficients.

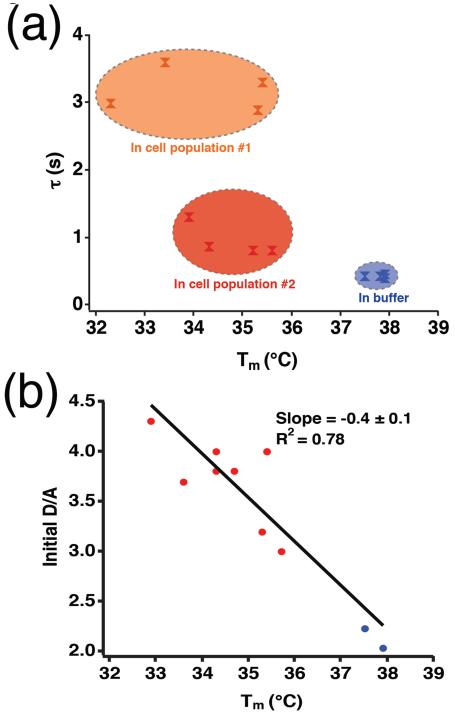

Figure 6.

Distinct populations inside cells: (a) T-jump relaxation time τ vs. melting temperature Tm. (b) Negative correlation between D/A ratio at 25 °C vs. Tm (red dots: in cell; blue dots: in aqueous buffer).

kobs is weakly temperature dependent inside cells (see Fig. S3b), as was also observed for PGK.26 At Tm, τ ranged from 0.8 to 3.6 s, with an average of 1.9 ± 1.2 s (Fig. 3a, and Table 2 in SI). This average is 4.5 times slower than τ aqueous buffer (0.4 s), with a distribution that again does not overlap the aqueous buffer distribution at all. In contrast, PGK-FRET was only 2 times slower in-cell than aqueous buffer, and the fast end of the relaxation time distribution overlapped the in vitro value. For PGK-FRET the factor of 2 slow-down compared to aqueous solution was attributed mostly to a change in local viscosity and hence diffusion coefficient Dwater/Dcell ≈ 2.27 For VlsE we do not have the average Phi value to distinguish barrier effects from viscosity effects,28 so either our VlsE construct samples higher local viscosity than our PGK construct (Dwater/Dcell ≈ 4.5), or, if the viscosity sampled by VlsE is the same as for PGK, there is a 50% contribution from a slightly increased average folding barrier in cells (ΔΔG† ≈ RTln(4.5/2) ≈ 2 kJ/mole).

Kinetically distinct protein populations exist inside cells

We observe three lines of evidence for distinct VlsE populations inside U2OS cells: kinetically distinct populations, non-exponential kinetic traces, and different thermodynamic stabilities for native states of different compactness.

Fig. 6a plots relaxation time τ vs. melting temperature Tm for all 8 cells in which kinetics and thermodynamics were measured together. While proteins in different cells are not distinguished by their thermodynamic stability, the cells fall into two kinetic populations, both slower than the relaxation kinetics in aqueous buffer. The order of measurement had no relationship with ‘faster’ or ‘slower’ cells, thus the probability of the two populations arising from a single-peaked probability distribution is only p≈0.03 by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.29 The populations are kinetically distinct with 97% probability.

In contrast to β = 0.96 ± 0.02 in aqueous buffer, the average value of β was 0.87 ± 0.05 in the 8 cells for which kinetics were measured. β ranged as low as 0.6 ± 0.1 and as high as 1.1 ± 0.1. Thus some cells’ β deviated significantly below the β =1 expected for a single exponential function. This result could be explained by two limiting cases. 1) Either the folding mechanism has become multi-state inside the cell; 2) or the proteins are still two-state folders, but exist in 2 or more populations with different relaxation rates, so that averaging over the whole cell yields a non-exponential decay. A simulation in Fig. S4 shows that β = 0.87 is consistent with case 2), assuming in-cell variations of rates are similar to cell-to-cell variations of rates. Cytoplasmic heterogeneity of two-state relaxation rates accounts quantitatively for the observed smaller value of β in cells, but multi-state mechanisms cannot be ruled out, especially in cells with β>1.

As discussed earlier, the D/A ratio in-cell is on average greater than aqueous buffer (larger end-to-end distance in the cell). In addition, the D/A ratio in-cell also varies more (± 0.7 range, instead of the ± 0.1 range aqueous buffer that defines our measurement error). Plotting the D/A ratio at ≈25 °C against Tm yields a significant inverse correlation (R2 = 0.78 in Fig. 6b; additional experiments in Fig. S1b). In-cell folded VlsE populations that have the largest end-to-end distances are less stable; proteins with smaller end-to-end distances are more stable. This is consistent with simple crowding because more compact states should be more stable than less compact states in a crowded matrix.

Discussion

We can draw two main conclusions from our data. 1) The extracellular protein VlsE-FRET is destabilized inside the cytoplasm of U2OS cells, while the cytoplasmic enzyme PGK-FRET is stabilized. The previously observed stabilization of PGK inside cells cannot be extrapolated to extracellular proteins. Extracellular proteins that are synthesized in the cytoplasm, but end up unfolded and translocated outside the membrane to work as receptors, adhesion molecules, etc. constitute approximately ~20%-30% of cellular proteins, so there could be more such destabilized proteins.30 2) VlsE-FRET is stabilized by the carbohydrate crowder Ficoll yet destabilized in the cell. While PGK stability changes can be rationalized by simple volume exclusion both in a Ficoll matrix and in cells, explaining VlSE stability and folding will either require effects beyond crowding, or a structure-dependent volume exclusion mechanism.

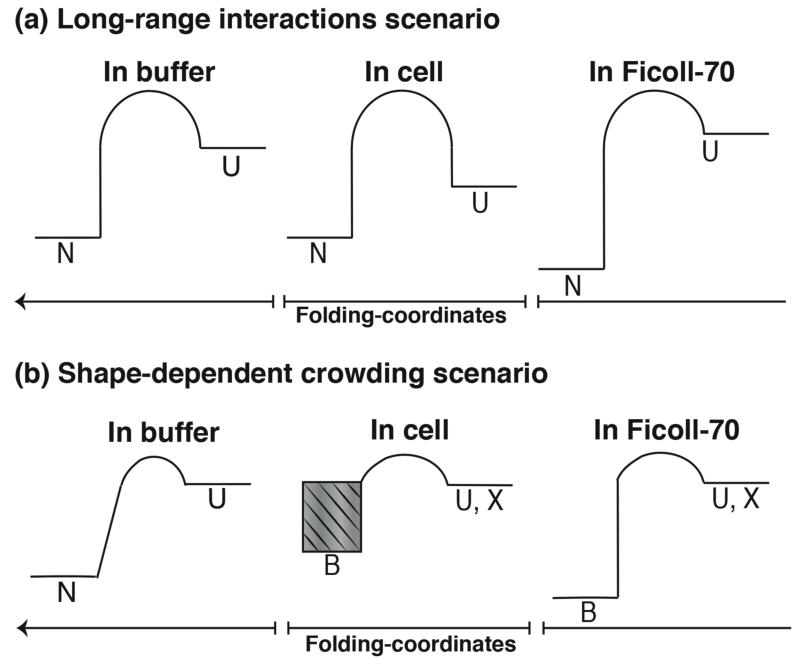

We propose two scenarios in Fig. 7 to account for the destabilization of VlsE inside cells and its stabilization by the synthetic crowder Ficoll: 1) Long-range interactions present in the cell but absent in Ficoll that overcome the excluded volume effect; 2) Short range structure-dependent excluded volume effects that differ between the cell and Ficoll environments. More proteins with different surface charge and shapes will have to be studied to confirm whether the “Long range interactions” scenario or the “Shape-dependent crowding” scenario is more prevalent.

Figure 7.

Simplified energy landscapes demonstrating how (a) the long-range electrostatic scenario, and (b) the shape-dependent crowding scenario can rationalize VlsE destabilization inside cells and VlsE stabilization in Ficoll, relative to aqueous buffer experiments.

In the long-range interactions scenario (Fig. 7, top), Ficoll and the cytoplasm act differently: in Ficoll buffer, the less compact unfolded U state is destabilized entropically, whereas the compact native state N is relatively unaffected. As a result there is a net increase in the folding free energy. In the cytoplasm, with its more complex mix of charged and uncharged crowders (including nucleic acids such as tRNA and charged proteins in addition to neutral carbohydrates), the state U could favorably interact with crowders, such as sticking to their surfaces. This enthalpic effect could overcome entropic destabilization of U, resulting in a net decrease of the folding free energy.

In the shape-dependent crowding scenario (Fig. 7, bottom), the different shapes of the X and B states proposed by Homouz et al. come into play. The B state is a more compact bean-shaped version of the normally elongated native state N, and the X state is a more compact version of the unfolded state U. In aqueous buffer (left), a simple two-state interconversion between N and U occurs. When Ficoll is added (right), B becomes the favored ground state of the system replacing N, and it is stabilized so much that the usual crowding effect is seen: the more compact folded state is stabilized relative to the less compact unfolded state. In the cell (middle), an intermediate effect is observed. B is stabilized just as in Ficoll, but not by as much, and to a varying degree from cell to cell (hatched band in Fig. 7). Thus the B-U folding free energy is not as favorable as N-U was in buffer, or as B-U was in Ficoll, and the compact protein is destabilized relative to the unfolded protein.

The two scenarios are not mutually exclusive, and indeed, different points speak in favor or against either alone. We give a few examples. Against shape-dependent crowding: Fig. 6b shows that B-like states with larger D/A ratios (characteristic of the B state according to Fig. S5b) result in a less stable protein; but then N-like states with smaller D/A ratio would be more stable in cells than B-like states. In favor of shape dependent crowding: The D/A ratio (end-to-end distance) in Fig. 4a is larger at room temperature in the cells vs. aqueous buffer. This matches the simulations by Homouz et al.11 because the more compact B state has a larger end-to-end distance than the N state (Fig. S5b). Against long-range interactions: The isoelectric points of VlsE and PGK are 7.11 and 6.98, leading to negligible charge differences at pH ≈ 7 in the cytoplasm. Visualization of both proteins with VMD31 shows that the small net charge is evenly distributed over the surface of both proteins. Thus differences in long-range electrostatics do not seem a very likely cause for differential destabilization of the two proteins in the cell. In favor of long-range interactions: Electrostatics are not the only possible interaction stabilizing U. Hydrophobic contacts of the unfolded VlsE, more likely in a complex crowding matrix than in Ficoll buffer, could stabilize the unfolded state when it sticks to cellular crowders.

The kinetic and thermodynamic evidence for the presence of different structural states such as N or B at low temperature, and U or X at high temperature, is mixed. As shown in Fig. 6a, based on melting temperatures Tm no distinct populations exist, but kinetically there appear to be two distinct populations. If the effect is purely energetic, this would require the activation free energies to be modulated by different cells, but not the folding free energies, which seems somewhat unlikely considering the average Phi value for proteins is closer to 0.3 than 0. A simple explanation would be that the cell populations differ in local viscosity: such a variation would affect only the rate (via the prefactor), but not the stability. We currently do not have the capability, but simultaneous fluorescence anisotropy (protein rotation) measurements could elucidate whether viscosity variations are indeed responsible for rate changes while stability remains unchanged.

In other respects, the cellular environment has similar effects on VlsE as it does on PGK. The folding rate of both proteins is modulated from cell to cell.27 There is some evidence of a change in folding mechanism, caused by ~RT~2 kJ/mole modulation of the protein energy landscape. In PGK, a change from stretched (β < 1) to single exponential behavior (β =1) was seen in the endoplasmic reticulum,21 an unambiguous sign that the mechanism is becoming more two-state-like. In VlsE, some cells have β > 1 (albeit barely so), which can only arise if the folding mechanism becomes less two-state-like (see SI). The average change of β from ≈1 to ≈ 0.87 on the other hand can be explained for both proteins by rate variations within the cytoplasm.32 The changes are not drastic for either protein; the in-cell environment, despite all its chaperones and a cytoplasmic composition that makes (un)folding more reversible,5 does not fundamentally alter the folding stability or kinetics, but rather fine-tunes the energy landscape of the protein to change Tm by a few °C or rates by a factor of 2-4.

Comparing our data with previous in Ficoll buffer experiments utilizing synthetic polymers as crowding agents, we see that at this time there is not yet a general rule to predict if a protein will be stabilized or destabilized inside cells, and how much of an effect short range (crowding) vs. long range (electrostatics or other protein-matrix interactions) will play. Both effects motivate further the idea that the cell can modulate the stability and folding of proteins differently in different situations, depending on what function and type of interactions a protein has. Such weak interactions, or ‘quinary structure,’33 could allow cells to control protein function and lifecycle beyond the level of tightly bound complexes, post-translational modification, ubiquitination, or other mechanisms that rely on covalent bonds or high affinity interactions to control proteins. In effect, such interactions would amount to ‘post-post-translational’ control of proteins within the cell.

Methods

Protein engineering and expression

The VlsE sequence without the N-terminal lipidation-signal was obtained from Pernilla Wittung-Stafshede (Umeå University) in the T7/NT-TOPO expression plasmid. We designed a VlsE construct fused between a Green Fluorescent Protein (AcGFP1) donor (D) and a mCherry acceptor (A). The construct melts at a lower temperature in vitro (and in-cell) than the unlabeled wild type, so folding experiments can be carried out in U2OS cells without stressing the cell above 45 °C. AcGFP and mCherry were bought from Clontech. A linker of just two amino acids was use to connect the AcGFP, VlsE and mCherry proteins. The fusion construct was cloned into the pDream 2.1 expression plasmid (Genscript Corp.) containing a C-terminus His-tag sequence (to facilitate purification) and a T7 promoter.

BL21(DE3) pLysS (Stratagene) competent cells were transformed with the pDream 2.1 VlsE expressing vector and grown overnight on LB plates with 100 μg/mL ampicillin at 37 °C. The VlsE-FRET protein could only be expressed in BL21(DE3) pLysS competent cells due to its toxicity. One colony was selected and grown overnight in 600 mL of LB media containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 34 μg/mL of chloramphenicol at 37 °C. Subsequently, 100 mL of the overnight culture was transferred to 1 L of LB cultures, up to 6 L. The cultures were grown in LB medium, and protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG (Inalco) at OD600=0.60. After induction, the cultures were grown overnight at room temperature. The cells were pelleted, resuspended in 10 mL of lysis buffer per 1L of cells (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 7.6) and lysed by ultrasonication.

The lysate was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm, and the supernatant was filtered through 0.22 μm syringe filter and loaded on a 1 mL Ni-NTA column (Qiagen). The protein was eluted with elution buffers (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 100 mM imidazole, pH 7.6) after a gradient wash with wash buffers containing different Imidazole concentrations (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 20-500 mM imidazole, pH 7.6). The presence of the eluted protein in the fractions was verified with SDS-PAGE. The fractions were combined and dialyzed against storage buffer (10 mM potassium phosphate). The protein was concentrated by Millipore centrifugal filter MWCO 10,000. The VlsE-FRET concentration was determined by measuring absorbance at 475 nm and using the AcGFP1 extinction coefficient (32,500 L mol−1 cm−1) with a UV-VIS spectrometer (Shimadzu). The molecular weight of the purified VlsE-FRET was confirmed by low-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI MS) and the purity of the protein was assessed by SDS-PAGE.

Cell culture, transfection and sample preparation

U2OS cells were cultured and grown to 50-60% confluency in DMEM supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin (PS) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The transfection with the pDream 2.1 vector containing the VlsE-FRET gene and CMV promoter was performed with Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Four hours after transfection, cell were split and grown on coverslips overnight at 37 °C. 24 hours after transfection an imaging chamber was prepare between the coverslip and a standard 2.5×7.5 cm microscope slide, separated by a 120 μm spacer (Grace BioLabs) to form an imaging chamber filled with Leibovitz L-15 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 30 % FBS. For measurements in aqueous buffer or Ficoll buffer, the same coverslip, slides and spacers were used, but instead a 3 μM solution of VlsE-FRET in 10 mM potassium phosphate was transferred into the imaging chamber. Micrometer-sized dye beads on the coverslip ensured that the objective focus was at the surface of the slide just as for cells, to avoid any temperature gradient across the chamber.

Fluorescence relaxation imaging (FReI)

The FReI instrument is explained in detail in refs. 5; 21. To collect the equilibrium data, donor and acceptor fluorescence were acquired for 4 s from room temperature to around 49 °C. For about half the cells, kinetics were measured immediately after the equilibrium data. A 4 °C temperature step was applied by an infrared diode laser at 2200 nm with 32 ms dead time.5 The red acceptor and green donor images were projected onto a CCD camera. The initial acceptor intensity was scaled by a factor a so that D-aA at the beginning of the video was equal to 0 and then D-aA (scaled D-A) was plotted against time. Relaxation towards the new equilibrium was recorded for 9 s. The data in Fig. 3 were corrected for a small linear bleaching baseline (which was fitted to the data between 6 and 9 s) and for a fast (~0.09 s) relaxation due to GFP internal dynamics (see SI). Global fitting was used to fit only one baseline and GFP relaxation time for all measurements in a given experiment, reducing the number of fitting parameters. Experiments done on PGK-FRET in U2OS cells with the same protocols confirmed the result from ref. 32 that PGK is stabilized by ca. 3 °C in-cell compared to in vitro.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Unlike phosphoglycerate kinase, VlsE-FRET is significantly destabilized inside cells.

VlsE-FRET has two kinetically distinct populations inside cells.

The macromolecular crowding effect is either modulated by long-range forces or shape-dependent.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (MCB 1019958). The National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program supported IG. We thank Anna Jean Wirth for performing comparative PGK-FRET melting experiments inside cells.

References

- 1.Dobson CM. Principles of protein folding, misfolding and aggregation. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2004;15:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Los Rios P, Ben-Zvi A, Slutsky O, Azem A, Goloubinoff P. Hsp70 chaperones accelerate protein translocation and the unfolding of stable protein aggregates by entropic pulling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:6166–6171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510496103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellis RJ. Molecular chaperones: avoiding the crowd. Current Biology. 1997;7:R531–R533. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00273-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agashe VR, Hartl FU. Roles of molecular chaperones in cytoplasmic protein folding. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2000;11:15–25. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1999.0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebbinghaus S, Dhar A, McDonald JD, Gruebele M. Protein folding stability and dynamics imaged in a living cell. Nature Methods. 2010;7:319–323. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ignatova ZZ, Krishnan BB, Bombardier JPJ, Marcelino AMCA, Hong JJ, Gierasch LML. From the test tube to the cell: exploring the folding and aggregation of a beta-clam protein. Biopolymers. 2007;88:157–163. doi: 10.1002/bip.20665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minton AP. Implications of macromolecular crowding for protein assembly. Curr. Op. Struct. Biol. 2000;10:34–39. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minton AP. Models for excluded volume interaction between an unfolded protein and rigid macromolecular cosolutes: Macromolecular crowding and protein stability revisited. Biophys. J. 2005;88:971–985. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.050351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung MS, Klimov D, Thirumalai D. Molecular crowding enhances native state stability and refolding rates of globular proteins. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:4753–4758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409630102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samiotakis A, Wittung-Stafshede P, Cheung MS. Folding, Stability and Shape of Proteins in Crowded Environments: Experimental and Computational Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009;10:572–588. doi: 10.3390/ijms10020572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Homouz D, Perham M, Samiotakis A, Cheung MS, Wittung-Stafshede P. Crowded, cell-like environment induces shape changes in aspherical protein. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:11754–11759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803672105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perham M, Stagg L, Wittung-Stafshede P. Macromolecular crowding increases structural content of folded proteins. FEBS Letters. 2007;581:5065–5069. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miklos AC, Sarkar M, Wang Y, Pielak GJ. Protein Crowding Tunes Protein Stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:7116–7120. doi: 10.1021/ja200067p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denos S, Dhar A, Gruebele M. Crowding effects on the small, fast-folding protein lambda(6-85) Faraday Discussions. 2012;157:451–462. doi: 10.1039/c2fd20009k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Li C, Pielak GJ. Effects of Proteins on Protein Diffusion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:9392–9397. doi: 10.1021/ja102296k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SJ, Dumont C, Gruebele M. Simulation-based fitting of protein-protein interaction potentials to SAXS experiments. Biophys. J. 2008;94:4924–4931. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.123240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiao M, Li HT, Chen J, Minton AP, Liang Y. Attractive Protein-Polymer Interactions Markedly Alter the Effect of Macromolecular Crowding on Protein Association Equilibria. Biophys. J. 2010;99:914–923. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou H-X. Polymer crowders and protein crowders act similarly on protein folding stability. FEBS Letters. 2013;587:394–397. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghaemmaghami S, Oas TG. Quantitative protein stability measurement in vivo. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2001;8:879–882. doi: 10.1038/nsb1001-879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlesinger APA, Wang YY, Tadeo XX, Millet OO, Pielak GJG. Macromolecular crowding fails to fold a globular protein in cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:8082–8085. doi: 10.1021/ja201206t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhar A, Girdhar K, Singh D, Gelman H, Ebbinghaus S, Gruebele M. Protein Stability and Folding Kinetics in the Nucleus and Endoplasmic Reticulum of Eucaryotic Cells. Biophys. J. 2011;101:421–430. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.05.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhar A, Samiotakis A, Ebbinghaus S, Nienhaus L, Homouz D, Gruebele M, Cheung MS. Structure, function, and folding of phosphoglycerate kinase are strongly perturbed by macromolecular crowding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:17586–17591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006760107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones K, Wittung-Stafshede P. The largest protein observed to fold by two-state kinetic mechanism does not obey contact-order correlation. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125:9606–9607. doi: 10.1021/ja0358807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones K, Guidry J, Wittung-Stafshede P. Characterization of surface antigen from Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;289:389–94. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Girdhar K, Scott G, Chemla YR, Gruebele M. Better biomolecule thermodynamics from kinetics. J. Chem. Phys. 2011;135:015102. doi: 10.1063/1.3607605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo MH, Xu YF, Gruebele M. Temperature dependence of protein folding kinetics in living cells. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:17863–17867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201797109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dhar A, Ebbinghaus S, Shen Z, Mishra T, Gruebele M. The Diffusion Coefficient for PGK Folding in Eukaryotic Cells. Biophys. J. 2010;99:L69–L71. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fersht AR. Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science: a Guide to Enzyme Catalysis and Protein Folding. W.H. Freeman; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peacock JA. Two-dimensional goodness-of-fit testing in astronomy. Monthly Notices Roy. Astron. Soc. 1983;202:615–627. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanderson CM. A new way to explore the world of extracellular protein interactions. Genome Research. 2008;18:517–520. doi: 10.1101/gr.074583.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Humphrey WF, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ebbinghaus S, Gruebele M. Protein folding landscapes in the living cell. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2011;2:314–319. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McConkey E. Molecular evolution, intracellular organization, and the quinary structure of proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1982;79:3236–3240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.10.3236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.