In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) surveillance study, out-of-hospital fatal coronary heart disease (CHD) declined more slowly than total fatal CHD over 1987-2008;1 however, the upper age limit was 74 and temporal changes in risk factors and preventive therapies were not considered. To evaluate secular trends in CHD, fatal CHD, and out-of-hospital fatal CHD in a broader age range accounting for changes in risk factors and therapies, we used data from the ARIC cohort study,2 the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS),3 and the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study.4 ARIC and CHS data were obtained as limited datasets from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute data repository. REGARDS data were obtained from study investigators. Institutional review boards at participating centers approved these studies, and participants provided written informed consent. The University of Alabama at Birmingham institutional review board approved this project which conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

ARIC recruited participants aged 45-64 years from 4 United States communities between 1987 and 1989. We excluded 60 participants not in the limited dataset (n = 15,732). CHS recruited participants aged ≥65 years from 4 United States communities between 1989 and 1993. We excluded 93 participants not in the limited dataset and 39 who were neither black nor white (n = 5,756). REGARDS recruited black and white participants aged ≥45 years from the 48 continental United States between 2003 and 2007. We excluded 569 participants without follow-up data (n = 14,992 aged <65 years, n = 14,857 aged ≥65 years).

With the exception of family history of CHD, participant characteristics were defined similarly across populations. Participants in ARIC and REGARDS were asked about CHD before age 65 in mothers and 55 in fathers, and participants in CHS were asked about CHD before age 55 in brothers and sisters.

We included the first seven years of follow-up in each population. Participant follow-up and CHD adjudication was conducted by ARIC, CHS, and REGARDS study investigators as previously described.5-9 Additional cases were identified in ARIC through hospital discharge records and in CHS through Medicare hospitalization records. Fatal CHD included all deaths within 28 days of the index CHD event. Out-of-hospital fatal CHD was defined as fatal CHD that occurred without a hospitalization. Participants were censored at the time of a non-fatal CHD event. Myocardial infarction (MI) diagnosis became more sensitive between the late 1980s/1990s and the 2000s due to transition from creatine phosphokinase to troponin assays.10, 11 Therefore, MIs with maximum troponin <0.5 μg/L in REGARDS, which may not have been detectable in ARIC or CHS, were considered non-cases unless there were diagnostic electrocardiogram findings.

All analyses were stratified by age at baseline (45-64 or ≥65 years). Participant characteristics were summarized as means and standard deviations or percentages. We constructed Kaplan-Meier curves for CHD, fatal CHD, and out-of-hospital fatal CHD by time period. We calculated age-, race-, and sex-adjusted rates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) by time period overall and by history of CHD at baseline using Poisson models with over-dispersion parameters and an offset of natural logarithm of person-time. We calculated hazard ratios and 95% CIs comparing time periods using Cox hazards models adjusted for age, sex, race, diabetes, LDL cholesterol, lipid-lowering therapy, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medications, smoking, HDL cholesterol, family history of CHD, body mass index, and baseline history of CHD. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using an interaction term between time period indicator and natural logarithm of follow-up time; there was no evidence of violation. Two-side p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Compared to participants recruited 1987-1993 (ARIC and CHS), a larger proportion of 2003-2007 participants (REGARDS) were black, had diabetes, history of CHD, and family history of CHD, and used lipid lowering and antihypertensive medications (Table 1). LDL cholesterol and prevalence of smoking were lower and body mass index was higher in 2003-2007 than in 1987-1993.

Table 1. Study participant characteristics by age group and time period*.

| Age group | 45-64 years of age | ≥65 years of age | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time period | ARIC† (late 1980s/1990s) | REGARDS‡ (2000s) | CHS§ (late 1980s/1990s) | REGARDS‡ (2000s) |

|

|

||||

| N | 15,732 | 14,992 | 5,795 | 14,678 |

| Age, years | 54.2 (5.7) | 57.3 (4.9) | 72.3 (5.6) | 72.7 (5.9) |

| Sex (%) | ||||

| Male | 44.8 | 42.4 | 42.5 | 47.5 |

| Female | 55.2 | 57.6 | 57.5 | 52.5 |

| Race (%) | ||||

| Black | 27.1 | 43.9 | 15.7 | 38.3 |

| White | 72.9 | 56.1 | 84.3 | 61.7 |

| History of diabetes (%) | 12.0 | 20.3 | 15.7 | 23.8 |

| History of CHD (%) | 5.0 | 12.3 | 19.6 | 23.8 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 138 (39) | 117 (35) | 130 (36) | 110 (34) |

| Lipid-lowering therapy use (%) | 2.9 | 28.6 | 5.4 | 38.7 |

| Cigarette smoking (%) | ||||

| Current | 26.2 | 18.8 | 12.1 | 10.0 |

| Past | 32.1 | 35.1 | 41.4 | 45.6 |

| Never | 41.7 | 46.1 | 46.5 | 44.4 |

| Hypertension (%) | 34.9 | 52.6 | 65.8 | 65.8 |

| Antihypertensive medication use (%) | 25.5 | 47.6 | 47.5 | 59.7 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 52 (17) | 52 (16) | 54 (16) | 52 (16) |

| Family history of premature CHD (%) | 11.7 | 21.5 | 9.9 | 19.3 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.7 (5.4) | 30.2 (6.6) | 26.6 (4.1) | 28.5 (5.6) |

Numbers are mean (standard deviation) or percentages

ARIC: Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities cohort study population recruited 1987-1989

REGARDS: REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke study population recruited 2003-2007

CHS: Cardiovascular Health Study population recruited 1989-1993

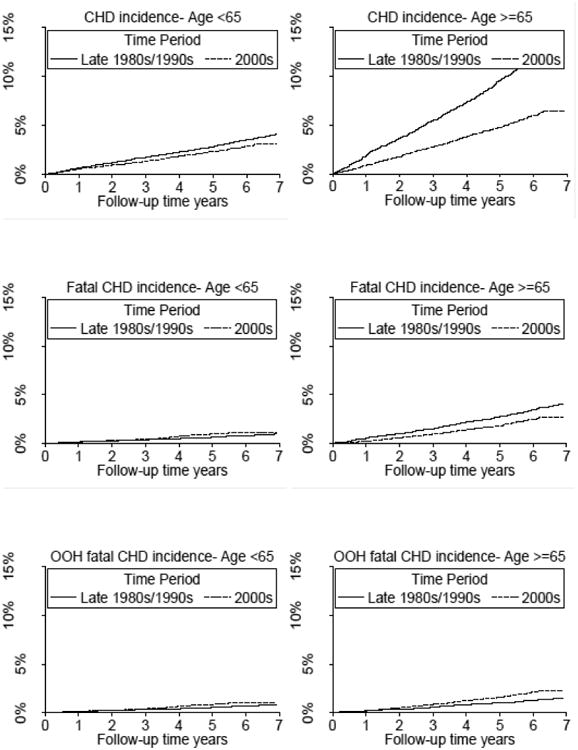

Unadjusted cumulative incidence of CHD and age-, race, and sex-adjusted CHD incidence rates were lower in the 2000s than in the late 1980s/1990s (Figure 1, Table 2). In fully-adjusted models, CHD incidence was lower in the 2000s than in the late 1980s/1990s (Table 3). After multivariable adjustment, fatal CHD was less common in the 2000s than the late 1980s/1990s, particularly for individuals with history of CHD. Unadjusted cumulative incidence of out-of-hospital fatal CHD was higher in the 2000s than in the late 1980s/1990s. The age-, race-, and sex-adjusted rates of out-of-hospital fatal CHD did not decline significantly between the late 1980s/1990s and the 2000s, except for the subgroup of individuals 45-64 years of age with a history of CHD at baseline. After multivariable adjustment, out-of-hospital fatal CHD was lower in the 2000s compared to the late 1980s/1990s among individuals ages 45-64 years. Among older adults with a history of CHD, there were no differences in out-of-hospital fatal CHD, and there was an increase in out-of-hospital fatal CHD among those without a history of CHD.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD) (top panel), fatal CHD (middle panel), and out-of-hospital (OOH) fatal CHD (bottom panel) for individuals <65 years of age (left panel) and ≥65 years of age (right panel) comparing the 2000s (REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke study population) to the late 1980s/1990s (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities cohort study population and Cardiovascular Health Study population).

Table 2. Rates of CHD, fatal CHD, and out-of-hospital fatal CHD in the late 1980s/1990s and 2000s.

| Time period | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Late 1980s/1990s* | 2000s† | ||||

|

|

|||||

| Cases | Age-, race-, and sex-adjusted rate per 1,000 person-years (95% CI) | Cases | Age-, race-, and sex-adjusted rate per 1,000 person-years (95% CI) | p-value | |

| CHD incidence | |||||

| Overall | |||||

| 45-64 years of age | 631 | 6.2 (5.7, 6.7) | 297 | 3.8 (3.4, 4.3) | <0.001 |

| ≥65 years of age | 732 | 20.8 (19.1, 22.7) | 619 | 9.0 (8.3, 9.8) | <0.001 |

| History of CHD at baseline | |||||

| 45-64 years of age | 169 | 35.4 (29.4, 42.6) | 110 | 13.9 (11.5, 16.9) | <0.001 |

| ≥65 years of age | 292 | 46.4 (40.6, 53.1) | 297 | 19.5 (17.2, 22.2) | <0.001 |

| No history of CHD at baseline | |||||

| 45-64 years of age | 442 | 4.8 (4.3, 5.3) | 180 | 2.8 (2.4, 3.3) | <0.001 |

| ≥65 years of age | 440 | 15.7 (14.1, 17.5) | 317 | 6.3 (5.6, 7.0) | <0.001 |

| Fatal CHD | |||||

| Overall | |||||

| 45-64 years of age | 146 | 1.5 (1.2, 1.8) | 117 | 1.4 (1.2, 1.7) | 0.5 |

| ≥65 years of age | 208 | 6.0 (5.1, 7.0) | 246 | 3.4 (3.0, 3.9) | <0.001 |

| History of CHD at baseline | |||||

| 45-64 years of age | 51 | 11.3 (8.2, 15.5) | 51 | 6.3 (4.7, 8.4) | 0.01 |

| ≥65 years of age | 130 | 21.1 (17.3, 25.8) | 127 | 8.2 (6.7, 9.9) | <0.001 |

| No history of CHD at baseline | |||||

| 45-64 years of age | 90 | 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) | 61 | 0.9 (0.7, 1.2) | 0.3 |

| ≥65 years of age | 78 | 2.9 (2.2, 3.7) | 118 | 2.2 (1.8, 2.6) | 0.04 |

| Out-of-hospital fatal CHD | |||||

| Overall | |||||

| 45-64 years of age | 125 | 1.3 (1.1, 1.5) | 105 | 1.3 (1.0, 1.6) | 0.7 |

| ≥65 years of age | 78 | 2.3 (1.8, 2.9) | 211 | 3.0 (2.6, 3.5) | 0.1 |

| History of CHD at baseline | |||||

| 45-64 years of age | 44 | 9.6 (6.8, 13.5) | 47 | 5.7 (4.2, 7.8) | 0.02 |

| ≥65 years of age | 44 | 7.2 (5.2, 9.9) | 107 | 7.1 (5.7, 8.8) | 0.8 |

| No history of CHD at baseline | |||||

| 45-64 years of age | 78 | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) | 54 | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.3 |

| ≥65 years of age | 34 | 1.3 (0.9, 1.9) | 103 | 2.0 (1.6, 2.5) | 0.1 |

CHD: coronary heart disease, CI: confidence interval

Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities study population (individuals 45-64 years of age) and Cardiovascular Health Study population (individuals ≥65 years of age)

REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke study population

Table 3. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for CHD, fatal CHD, and out-of-hospital fatal CHD comparing the 2000s (REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke study population) to the late 1980s/1990s (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities cohort study population and Cardiovascular Health Study population).

| Age-, sex-, race-adjusted | Multivariable-adjusted* | |

|---|---|---|

| CHD incidence | ||

| Overall | ||

| 45-64 years of age | 0.64 (0.55, 0.74) | 0.58 (0.46, 0.73) |

| ≥65 years of age | 0.45 (0.40, 0.51) | 0.45 (0.38, 0.53) |

| History of CHD at baseline | ||

| 45-64 years of age | 0.40 (0.31, 0.52) | 0.30 (0.19, 0.48) |

| ≥65 years of age | 0.42 (0.36, 0.50) | 0.42 (0.32, 0.55) |

| No history of CHD at baseline | ||

| 45-64 years of age | 0.62 (0.51, 0.74) | 0.73 (0.56, 0.95) |

| ≥65 years of age | 0.44 (0.37, 0.51) | 0.48 (0.38, 0.59) |

| Fatal CHD | ||

| Overall | ||

| 45-64 years of age | 1.02 (0.78, 1.33) | 0.69 (0.44, 1.09) |

| ≥65 years of age | 0.62 (0.51, 0.75) | 0.60 (0.45, 0.79) |

| History of CHD at baseline | ||

| 45-64 years of age | 0.60 (0.39, 0.92) | 0.23 (0.10, 0.53) |

| ≥65 years of age | 0.41 (0.32, 0.53) | 0.44 (0.30, 0.66) |

| No history of CHD at baseline | ||

| 45-64 years of age | 0.96 (0.67, 1.37) | 1.10 (0.66, 1.85) |

| ≥65 years of age | 0.88 (0.64, 1.20) | 0.95 (0.61, 1.46) |

| Out-of-hospital fatal CHD | ||

| Overall | ||

| 45-64 years of age | 1.06 (0.80, 1.41) | 0.64 (0.39, 1.05) |

| ≥65 years of age | 1.43 (1.08, 1.90) | 1.35 (0.92, 1.96) |

| History of CHD at baseline | ||

| 45-64 years of age | 0.65 (0.42, 1.03) | 0.26 (0.11, 0.62) |

| ≥65 years of age | 1.03 (0.71, 1.51) | 1.04 (0.61, 1.76) |

| No history of CHD at baseline | ||

| 45-64 years of age | 0.96 (0.65, 1.40) | 0.99 (0.56, 1.74) |

| ≥65 years of age | 1.79 (1.16, 2.76) | 2.03 (1.15, 3.57) |

CHD: coronary heart disease

Adjusted for age, sex, race, history of diabetes, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, lipid-lowering therapy use, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, smoking, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, family history of CHD, body mass index, and baseline history of CHD (overall population only)

Strengths of this report include prospective data collection, adjudicated CHD, wide age range, and large number of black and white participants. There are also limitations. Data collection varied across populations. Because of the methods for detecting non-fatal CHD events, a greater proportion of nonfatal events were likely captured in ARIC and CHS than REGARDS. However, all studies employed active follow-up and vital records to detect deaths. Diagnosis of MI has increased in sensitivity. We excluded cases in REGARDS diagnosed because of small troponin elevations that may not have been detected previously. The studies drew participants from different underlying populations. Differences between studies could have contributed to observed differences in CHD.

In summary, our results suggest that over the past 25 years out-of-hospital fatal CHD rates did not improve substantially among middle-aged adults and increased among older adults. Our results extend those from prior studies by adjusting for changes in risk factors and use of preventive medications. Reducing out-of-hospital CHD death should be a focus of research and prevention efforts.

Acknowledgments

The REGARDS project is supported by a cooperative agreement U01 NS041588 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and grants R01 HL 080477 and K24 HL111154 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the REGARDS study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating REGARDS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.regardsstudy.org. This investigation, including design and conduct of the study, was supported by Amgen, Inc. The authors conducted all analyses and maintained the rights to publish this manuscript.

Disclosures: The authors received research support from Amgen, Inc. Dr Muntner has served as a consultant for Amgen, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rosamond WD, Chambless LE, Heiss G, Mosley TH, Coresh J, Whitsel E, Wagenknecht L, Ni H, Folsom AR. Twenty-two–year trends in incidence of myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease mortality, and case fatality in 4 US communities, 1987–2008. Circulation. 2012;125:1848–1857. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.047480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The ARIC investigators. The Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, Furberg CD, Gardin JM, Kronmal RA, Kuller LH, Manolio TA, Mittelmark MB, Newman A, O'Leary DH, Psaty B, Rautaharju P, Tracy RP, Weiler PG. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1:263–276. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, Gomez CR, Go RC, Prineas RJ, Graham A, Moy CS, Howard G. The REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25:135–143. doi: 10.1159/000086678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ives DG, Fitzpatrick AL, Bild DE, Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Crowley PM, Cruise RG, Theroux S. Surveillance and ascertainment of cardiovascular events. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:278–285. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White AD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Sharret AR, Yang K, Conwill D, Higgins M, Williams OD, Tyroler HA. Community surveillance of coronary heart disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study: methods and initial two years' experience. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:223–233. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parmar G, Ghuge P, Halanych JH, Funkhouser E, Safford MM. Cardiovascular outcome ascertainment was similar using blinded and unblinded adjudicators in a national prospective study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1159–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halanych JH, Shuaib F, Parmar G, Tanikella R, Howard VJ, Roth DL, Prineas RJ, Safford MM. Agreement on cause of death between proxies, death certificates, and clinician adjudicators in the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:1319–1326. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luepker RV, Apple FS, Christenson RH, Crow RS, Fortmann SP, Goff D, Goldberg RJ, Hand MM, Jaffe AS, Julian DG, Levy D, Manolio T, Mendis S, Mensah G, Pajak A, Prineas RJ, Reddy KS, Roger VL, Rosamond WD, Shahar E, Sharrett AR, Sorlie P, Tunstall-Pedoe H. Case definitions for acute coronary heart disease in epidemiology and clinical research studies: a statement from the AHA Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; AHA Statistics Committee; World Heart Federation Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Epidemiology and Prevention; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation. 2003;108:2543–2549. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000100560.46946.EA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myocardial infarction redefined—a consensus document of the Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:1502–1513. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD. Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116:2634–2653. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]