Abstract

The manuscript surveys the history of psychopathic personality, from its origins in psychiatric folklore to its modern assessment in the forensic arena. Individuals with psychopathic personality, or psychopaths, have a disproportionate impact on the criminal justice system. Psychopaths are twenty to twenty-five times more likely than non-psychopaths to be in prison, four to eight times more likely to violently recidivate compared to non-psychopaths, and are resistant to most forms of treatment. This article presents the most current clinical efforts and neuroscience research in the field of psychopathy. Given psychopathy’s enormous impact on society in general and on the criminal justice system in particular, there are significant benefits to increasing awareness of the condition. This review also highlights a recent, compelling and cost-effective treatment program that has shown a significant reduction in violent recidivism in youth on a putative trajectory to psychopathic personality.

Psychopaths consume an astonishingly disproportionate amount of criminal justice resources. The label psychopath is often used loosely by a variety of participants in the system—police, victims, prosecutors, judges, probation officers, parole and prison officials, even defense lawyers—as a kind of lay synonym for incorrigible. Law and psychiatry, even at the zenith of their rehabilitative optimism, both viewed psychopaths as a kind of exception that proved the rehabilitative rule. Psychopaths composed that small but embarrassing cohort whose very resistance to all manner of treatment seemed to be its defining characteristic.

Psychopathy is a constellation of psychological symptoms that typically emerges early in childhood and affects all aspects of a sufferer’s life including relationships with family, friends, work, and school. The symptoms of psychopathy include shallow affect, lack of empathy, guilt and remorse, irresponsibility, and impulsivity (see Table 1 for a complete list of psychopathic symptoms). The best current estimate is that just less than 1% of all noninstitutionalized males age 18 and over are psychopaths.1 This translates to approximately 1,150,000 adult males who would meet the criteria for psychopathy in the United States today.2 And of the approximately 6,720,000 adult males that are in prison, jail, parole, or probation,3 16%, or 1,075,000, are psychopaths.4 Thus, approximately 93% of adult male psychopaths in the United States are in prison, jail, parole, or probation.

Table 1. The 20 Items Listed on the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (Hare 1991; 2003).

The items corresponding to the early two-factor conceptualization of psychopathy,89 subsequent three-factor model,90 and current four-factor model are listed.91 The two-factor model labels are Interpersonal-Affective (Factor 1) and Social Deviance (Factor 2); the three-factor model labels are Arrogant and Deceitful Interpersonal Style (Factor 1); Deficient Affective Experience (Factor 2), and Impulsive and Irresponsible Behavioral Style (Factor 3); the four-factor model labels are Interpersonal (Factor 1), Affective (Factor 2), Lifestyle (Factor 3), and Antisocial (Factor 4). Items indicated with “--” did not load on any factor.

| Item | 2 Factor Model | 3 Factor | 4 Factor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Glibness-Superficial Charm | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | Grandiose Sense of Self Worth | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | Need for Stimulation | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | Pathological Lying | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | Conning-Manipulative | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | Lack of Remorse or Guilt | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 7 | Shallow Affect | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 8 | Callous-Lack of Empathy | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 9 | Parasitic Lifestyle | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 10 | Poor Behavioral Controls | 2 | -- | 4 |

| 11 | Promiscuous Sexual Behavior | -- | -- | -- |

| 12 | Early Behavioral Problems | 2 | -- | 4 |

| 13 | Lack of Realistic, Long-Term Goals | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 14 | Impulsivity | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 15 | Irresponsibility | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 16 | Failure to Accept Responsibility | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 17 | Many Marital Relationships | -- | -- | -- |

| 18 | Juvenile Delinquency | 2 | -- | 4 |

| 19 | Revocation of Conditional Release | 2 | -- | 4 |

| 20 | Criminal Versatility | -- | -- | 4 |

Psychopathy is astonishingly common as mental disorders go. It is twice as common as schizophrenia, anorexia, bipolar disorder, and paranoia,5 and roughly as common as bulimia, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, and narcissism.6 Indeed, the only mental disorders significantly more common than psychopathy are those related to drug and alcohol abuse or dependence, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

No matter where one stands on the long-debated question of whether “nothing works” when it comes to criminal rehabilitation,7 there is no doubt that the psychopath has grossly distorted the inquiry. Psychopaths are not only much more likely than non-psychopaths to be imprisoned for committing violent crimes,8 they are also more likely to finagle an early release using the deceptive skills that are part of their pathologic toolbox,9 and then, once released, are much more likely to recidivate, and to recidivate violently.10

But this exasperating picture of the hidden and incorrigible psychopath may be changing. Neuroscience is beginning to open the hood on psychopathy. The scientist-author of this article has spent the last 15 years imaging the brains of psychopaths in prison, and has accumulated the world’s largest forensic database on the psychopathic brain. The findings from this data and others,11 summarized in Part IV, strongly suggest that all psychopaths share common neurological traits that are becoming relatively easy to diagnose using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).12 Additionally, researchers are beginning to report significant progress in treatment, especially, and most excitingly, in the treatment of juveniles with early indications of psychopathy.13

This paper will not attempt to answer the complex and controversial policy question of whether psychopathy should be an excusing condition under the criminal law, or even whether, the extent to which, and the direction in which a diagnosis of psychopathy should drive a criminal sentence.14 As science pushes the chain of behavioral causation back in time and deeper into the brain, it is all too tempting to label the latest cause as an excuse. But of course not every cause is an excuse. Whether “you” pulled the trigger on the gun, or your motor neurons did, or your sensory neurons, or neurons deeper in your cortical or subcortical systems, is not only a nonsensical question, it is a tautological inquiry that will never be able to answer the only pertinent moral and public policy question: should you be held responsible for your actions? That is, are you sufficiently rational to be blameworthy?15 Addressing difficult policy questions of how these new instruments to detect psychopathy and the new treatments for it might best be integrated into the criminal justice system are questions beyond the scope of this paper and should be the focus of future scholarly work.16

But even if a cause does not sufficiently disable an actor’s reason, and therefore does not rise to the level of excuse, that does not mean the system should not care about causes, especially at the punishment end. On the contrary, those involved in the criminal justice system have a moral obligation, not just to the people incarcerated but also to those on whom the temporarily incarcerated will be released, to do everything they can, within the constraints of the punitive purposes of imprisonment, to reduce recidivism. Given the facts that psychopaths make up such a disproportionate segment of people in prison and that they recidivate at substantially higher rates than non-psychopaths, the recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of psychopathy discussed in this paper are developments anyone concerned with the criminal justice system simply cannot ignore. Even a modest reduction in the criminal recidivism of psychopaths would significantly decrease the exploding public resources we devote to prisons, not to mention reduce the risks all of us face as potential victims of psychopaths.

This paper will survey the history of psychopathy (Part I), the impact psychopaths have on the criminal justice system (Part II), the traditional clinical assessments for psychopathy (Part III), the emerging neuroimaging findings (Part IV), and will finish with a discussion of recent treatment studies and their potential economic impacts (Part V).

I. A BRIEF HISTORY OF PSYCHOPATHY

A. Emptied Souls

The idea that some humans are inherent free riders without moral scruple seems to have become controversial only in the postmodern era, when it has become fashionable to deny that any of us have a “nature” at all. For as long as humans have roamed the Earth, we have noticed that there are people who seem to be what psychiatrist Adolf Guggenbühl-Craig called “emptied souls.”17 One of Aristotle’s students, Theophrastus, was probably the first to write about them, calling them “the unscrupulous.”18 These are people who lack the ordinary connections that bind us all and lack the inhibitions that those connections impose. They are, to over simplify, people without empathy or conscience.

Psychopathy has always been part of human society; that is evident from its ubiquity in history’s myths and literature.19 Greek and Roman mythology is strewn with psychopaths, Medea being the most obvious.20 Psychopaths populate the Bible, at least the Old Testament, perhaps beginning with Cain. Psychopaths have appeared in a steady stream of literature from all cultures since humans first put pen to paper: from King Shahyar in The Book of One Thousand and One Nights;21 to the psychopaths in Shakespeare, including Richard III and, perhaps most chillingly, Aaron the Moor in Titus Andronicus; to the villain Ximen Qing in the 17th century Chinese epic Jin Ping Mei, The Golden Vase.22 More recent sightings in film and literature include Macheath, from Berthold Brecht’s Three Penny Opera, Alex DeLarge in Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange, and Hannibal Lecter in Silence of the Lambs.23

No cultures, or stations, are immune. One of the modern fathers of the clinical study of psychopathy, Hervey Cleckley, famously opined that the Athenian general Alcibiades was probably a psychopath.24 And of course there was the Roman emperor Caligula. But psychopaths much more typically come from the ranks of the ordinary. Cleckley wrote extensively about ordinary patients he classified as having severe forms of psychopathy and whom he opined were almost all “plainly unsuited for life in any community; some are as thoroughly incapacitated, in my opinion, as most patients with unmistakable schizophrenic psychosis.”25 But he also examined patients who were highly functioning businessmen—men of the world as he put it—scientists, physicians and even psychiatrists. These people were able to navigate the demands of modern society, despite having the same clinical constellations as their less-functioning brethren, including grandiosity, impulsivity, remorselessness and shallow affect. These functioning psychopaths have become the objects of much recent attention.26

Although in this article we will focus on research efforts in the U.S. and Canada, psychopathy is a worldwide problem. In 1995, NATO commissioned an Advanced Study Institute on Psychopathic Behavior, the scientific director of which was Robert Hare, whose seminal clinical assessment instrument is discussed in detail in Part II below.27 One of the important collections on psychopathy, cited throughout this article, was the product of a 1999 meeting held under the auspices of the Queen of Spain and her Center for the Study of Violence.28 Also discussed below29 is the British practice of expressly addressing the problem of the psychopath in commitment statutes in ways that have been generally more aggressive, at least theoretically, than is done in North America.

Psychopaths also appear in existing preindustrial societies, suggesting they are not a cultural artifact of the demands of advancing civilization but have been with us since our emergence as a species. For example, the Yorubas, a tribe indigenous to southwestern Nigeria, call their psychopaths aranakan, which they describe as meaning “a person who always goes his own way regardless of others, who is uncooperative, full of malice, and bullheaded.”30 Inuits have a word, kunlangeta, that they use to describe someone whose “mind knows what to do but he does not do it,” and who repeatedly lies, steals, cheats, and rapes.31

While the capacity to identify with the thoughts and feelings of fellow human beings undoubtedly has innumerable cultural variations, it is beginning to be clear that evolution has built into the human brain a central core of moral reasoning that is more or less universal.32 It is that central core that is missing in psychopaths.

B. Psychopathy and Psychiatry

Psychopaths have hidden from psychiatry too. Well into the eighteenth century, medicine recognized only three broad classes of mental illness: melancholy (depression), psychosis, and delusion, and the psychopath fit into none of these. Even today, the bible of diagnostic psychiatry—the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) does not formally recognize psychopathy, but uses instead the largely subsuming diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD).33 ASPD was intended to be synonymous with psychopathy. But as discussed in more detail below,34 it has since become clear, if it was not at the time, that in their efforts to compromise the authors of the DSM missed the psychopathic mark. And yet, even though psychopathy has never fit comfortably into the psychiatric pigeonholes du jour, clinicians have long been noticing and documenting their encounters with people whose perceptive and logical faculties seemed entirely intact, but who nevertheless seemed profoundly incapable of making moral choices.

One of the first medical professionals to describe this population was the French doctor Phillipe Pinel, who in 1806 described the condition as maniaque sans délire, insanity without delirium.35 One of Pinel’s students, Jean Etienne Dominique Esquirol, called it la folie raisonnante, rational madness.36 Benjamin Rush dubbed it moral derangement.37 Moral insanity was another popular term that was prevalent in the United States and England throughout the 1800s and early 1900s.38

The term psychopathy comes from the German word psychopastiche, the first use of which is generally credited to the German psychiatrist J.L.A. Koch in 1888,39 and which literally means suffering soul. The term gained clinical traction through the first third of the 1900s, but for a time was replaced by sociopathy, which emerged in the 1930s. The two terms were often used interchangeably by clinicians and academics. Sociopathy was preferred by some because the lay public sometimes confused psychopathy with psychosis.40 Many professionals also preferred sociopathy because it evoked the notion that these antisocial behaviors were largely the product of environment, an opinion held by many at the time. In contrast, psychopathy evoked a deeper genetic, or at least developmental, cause.41 When the DSM-III introduced the broader diagnosis of ASPD in 1980,42 sociopathy and sociopath fell out of modern favor.

The causes of psychopathy, like the causes of most complex mental disorders, are not well understood. There is a growing body of evidence, including the research discussed in Part IV of this article, showing that psychopathy is highly correlated to aberrant neuronal activity in specific regions of the brain. Those neurological causes are in turn almost certainly either genetic or the product of very early developmental problems.43 Indeed, the clinical evidence of signs of psychopathy in very young children suggests that the classical blank slate model of the psychopath as the adult product of childhood maltreatment probably misses the mark.44 Although the question is still debated, many scholars of psychopathy have accepted an interactive model, in which the people who become psychopaths are seen as having a genetic or early developmental predisposition for the disorder, which then blossoms into psychopathy when the predisposed individual interacts with a poor environment.45

This is just one example of the nature versus nurture gnarl endemic to the larger question of why humans behave the way they do. Psychopathy is a particularly good example of why it is so difficult to tease out these causative influences. On the one hand, it is not difficult to imagine that a parent’s failure to bond with an infant could produce the kinds of neurological and clinical changes associated with psychopathy, and indeed there are many of these so-called “attachment theories” to explain a host of mental diseases. There are studies galore that correlate the neglect and abuse of children to those children growing up with increased risks of depression, suicide, violence, drug abuse and crime.46 But there are currently no studies that correlate these environmental factors to psychopathy. On the contrary, a paper Hare and his colleagues presented in 1990 shows that on average there is no detectable difference in the family backgrounds of incarcerated psychopaths and non-psychopaths.47 None of this means a baby born with a disposition for psychopathy is destined for it. But it does mean, as Hare has put it, “that their biological endowment—the raw materials that environmental, social, and learning experiences fashion into a unique individual—provides a poor basis for socialization and conscience formation.”48 As presented in Part V, there is new work suggesting that a certain type of therapy may be able to make up for this poor start and take young people with psychopathic predispositions off their psychopathic track. There is also evidence that even if young psychopaths cannot be cured, the environment in which they grow up is highly correlated to whether they will become criminal psychopaths or the kind of psychopaths who avoid crime and manage to function among us.49

Many psychiatrists at the turn of the century were uncomfortable with general descriptions of psychopathy as a lack of moral core. Such labels seemed more judgmental than scientific, a concern that no doubt touched a nerve of a young discipline already self-conscious about its early descriptive excesses and empirical voids. Psychiatrists like Henry Maudsley in England and J.L.A. Koch in Germany began thinking and writing about more comprehensive ways to describe the condition.50 Koch’s diagnostic criteria even found their way into the 8th edition of E. Kraepelin’s classic textbook on clinical psychiatry. But in exchange for more theoretical diagnostic clarity, the so-called German School of psychopathy expanded the diagnosis to include people who hurt themselves as well as others, and in the process seemed to lose sight of the moral disability that was at the core of the condition. By the time of the Great Depression, psychiatry was using the word psychopath to include people who were depressed, weak-willed, excessively shy and insecure—in other words, almost anyone deemed abnormal.51 The true psychopath had, once again, become academically, if not clinically, hidden.

This began to change in the late 1930s and early 1940s, largely as the result of the work of two men, the Scottish psychiatrist David Henderson and the American psychiatrist Hervey Cleckley. Henderson published his book Psychopathic States in 1939, and it instantly caused a reexamination of the German School’s broad approach. In it, Henderson focused on his observations that the psychopath is often otherwise perfectly normal, perfectly rational, and perfectly capable of achieving his abnormal egocentric ends. In America, Cleckley’s Mask of Sanity did very much the same. A minority of psychiatrists began to refocus on the psychopath’s central lack of moral reasoning, but with more diagnostic precision than had been seen before.

But orthodox psychiatry’s approach to psychopathy continued to be bedeviled by the conflict between affective traits, which traditionally had been the focus of the German School, and the persistent violation of social norms, which became a more modern line of inquiry. Almost everyone recognized the importance of the affective traits in getting at psychopathy, but many had doubts about clinicians’ abilities to reliably detect criteria such as callousness. It was this tension—between those who did and did not think the affective traits could be reliably diagnosed—that drove the swinging pendulum of the DSM’s iterations. Another organic difficulty with the notion of including psychopathy in a diagnostic and treatment manual is that these manuals were never designed for forensic use.52 Yet it has always been clear that one of the essential dimensions of psychopathy is social deviance, often in a forensic context.

The DSM, first published in 1952, dealt with the problem under the category Sociopathic Personality Disturbance, and divided this category into three diagnoses: antisocial reaction, dissocial reaction, and sexual deviation.53 It generally retained both affective and behavioral criteria, though it separated them into the antisocial and dissocial diagnoses. In 1968, the DSM-II lumped the two diagnoses together into the single category of antisocial personality, retaining both affective and behavioral criteria.54 The German tradition was finally broken in 1980 with the publication of the DSM-III, which for the first time defined psychopathy as the persistent violation of social norms, and which dropped the affective traits altogether, though it retained the label antisocial personality disorder.55

By dropping the affective traits dimension entirely, the DSM-III approach, and its 1987 revisions in DSM-III-R, ended up being both too broad and too narrow. It was too broad because by fixing on behavioral indicators rather than personality it encompassed individuals with completely different personalities, many of whom were not psychopaths. It was also too narrow because it soon became clear that the diagnostic artificiality of this norm-based version of ASPD was missing the core of psychopathy.56 This seismic definitional change was made in the face of strong criticism from clinicians and academics specializing in the study of psychopathy that, contrary to the framers of the DSM-III, had confidence in the ability of trained clinicians to reliably detect the affective traits.57 Widespread dissatisfaction with the DSM-III’s treatment of ASPD led the American Psychiatric Association to conduct field studies in an effort to improve the coverage of the traditional symptoms of psychopathy. The result was that the DSM-IV reintroduced some of the affective criteria the DSM-III left out, but in a compromise it provided virtually no guidance about how to integrate the two sets. As Robert Hare has put it, “An unfortunate consequence of the ambiguity inherent in DSM-IV is likely to be a court case in which one clinician says the defendant meets the DSM-IV definition of ASPD, another clinician says he does not, and both are right!”58

In the meantime, beginning in the 1980s, some clinicians began to rethink a working clinical definition of psychopathy. Based on Cleckley’s published criteria, Hare published his Psychopathy Checklist (PCL) in 1980,59 which he has since revised in 1991 and 2003 (PCL-R).60 In 1995, his colleagues authored the Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version (PCL: SV),61 and in 2003 Hare coauthored the Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version (PCL-YV).62 For many clinicians and researchers, these instruments, which are discussed in detail in Part II below, have become the standard diagnostic tool for psychopathy. They combine affective criteria (Factor 1) and socially deviant criteria (Factor 2) but do so with detailed rules for measuring those criteria to create a diagnostic score that has proven validity and high interrater reliability.63

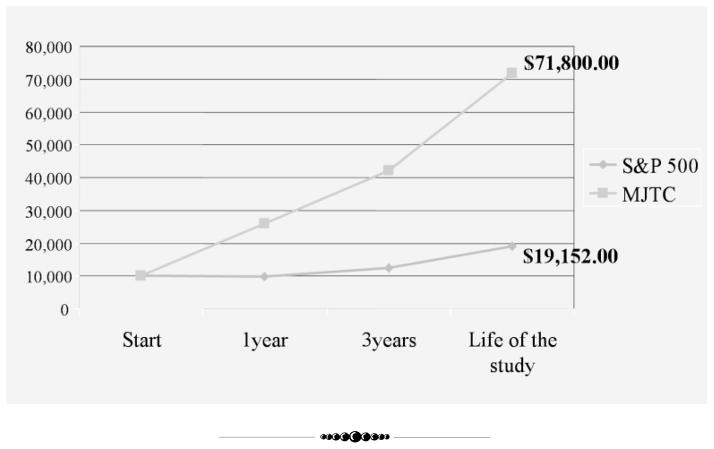

The relationship between Hare’s Psychopathy Factors and ASPD, at least in incarcerated populations,64 is depicted in Figure 1, which shows how ASPD fails to capture the affective traits (Factor 1) but does a good job of capturing the antisocial traits (Factor 2). Thus, ASPD-targeted treatment will do a good job of reaching prisoners with deviance trait disorders, including a large slice of psychopaths, but will miss almost half with Factor 1 affective disorders. Even more troubling, ASPD-targeted treatment will not be targeted at all because up to 85% of all prisoners suffer from ASPD.

Figure 1.

Antisocial Personality Disorder and Psychopathy Among Incarcerated Populations65

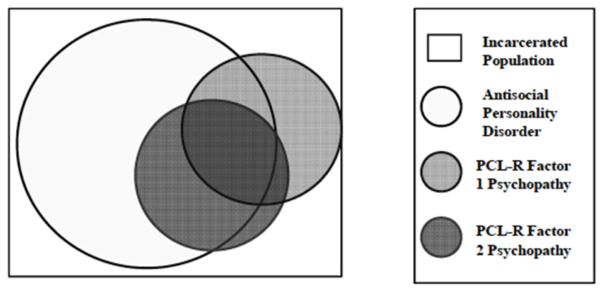

Figure 2 depicts the comorbidity of substance abuse and psychopathy for incarcerated populations, again using the Hare definition of psychopathy. Notice that the psychopaths with drug and alcohol problems make up a little less than half of all the incarcerated psychopaths. This means that about 10% of all of the drug treatment efforts in prison are potentially wasted at the outset (on half of the 20% who are psychopaths), unless treaters consider the influence of psychopathy on treatment. Psychopaths generally recidivate because they are psychopaths, not because they have drug problems.

Figure 2.

Drug Abuse-Dependence and Psychopathy Among Incarcerated Populations66

The Hare instruments have proved to be extremely useful, and, as discussed in more detail in Part II below, they are the gold standard for the clinical diagnosis of psychopathy. They have been translated into a dozen languages, and are used around the world. Yet, as we have already mentioned, the orthodox view as expressed in the DSM-IV, and now the DSM-IV-TR, does not recognize psychopathy as a condition separate from ASPD. The debate remains robust,67 though, like many issues with psychopathy, is asymmetric. There are dozens of peer-reviewed papers published each year that validate the assessment of psychopathy using the Hare criteria, but very few arguing that ASPD is the better diagnostic tool. The roots of this continuing, if decelerating, debate lie not only in the historical skepticism of describing a condition in moral, seemingly judgmental, terms, and in continuing doubts about the reliability of detecting the affective traits, but also in the problem of diagnostic tautology. Academic psychiatry is justifiably troubled by diagnostic criteria that include too many behavioral components. It is theoretically unsettling to define a condition as a mental disorder just because it is has been declared to be antisocial by the legal system.

C. Psychopathy and the Law

The law has treated psychopathy with the same benign neglect as psychiatry has, and for much longer. A case can be made, however, that the law’s blind eye has made more sense, at least when it comes to thinking of psychopathy as a potentially excusing mental disease. An institution dedicated to the regulation of social behaviors hardly could excuse a general class of miscreants simply because, well, they are miscreants. Early notions of insanity and other excusing doctrines were, like psychiatry, focused on subjects’ general inability to perceive the world around them and make judgments about that world—the lunatics, imbeciles, and children, as both psychiatry and the common law famously grouped together the legally blameless and incompetent.68

The law attributes all antisocial acts, psychopathic or no, to the same forces it attributes all acts of people whose reason is sufficiently intact to be presumed to have free will: a conscious judgment to violate social norms, usually for personal gain, and for which, once caught, they must be held responsible. It has never recognized that people whose central disability is that they chronically make antisocial choices should be excused for those antisocial behaviors. On the contrary, the persistently bad arguably should be punished more than the occasionally bad. This is the very difference between good people doing bad things, mad people doing bad things, and bad people doing bad things.

Reflecting these deep and long-standing notions of responsibility, in 1953 the American Law Institute adopted what has become known as the caveat paragraph in its definition of insanity, crafted specifically to exclude defenses smacking of psychopathy: “The terms ‘mental disease or defect’ do not include an abnormality manifested only by repeated criminal or otherwise antisocial conduct.”69 The Model Penal Code has retained the caveat paragraph,70 as has every state that has adopted the Model Penal Code definition of insanity, either in its statutory definition of insanity or in its stock jury instructions, or both.71 In the federal courts, before the adoption of the Insanity Defense Reform Act of 1984,72 every Circuit save two adopted the caveat paragraph as a matter of federal common law.73 The 1984 federal Act adopted a non-Model Penal Code definition of insanity that did not include anything like the caveat paragraph,74 but we have been unable to find a single reported post-1984 federal case suggesting that psychopathy is a qualifying mental disease or defect within the federal definition of insanity. The idea that psychopathy could be an excusing condition appears to be as dead a letter as there ever is in law.

And yet this dead letter seems to be stirring a bit in the academy. As we are coming to learn that moral cognition is not a tabula rasa, but has some deeply rooted evolutionary and neurological attributes,75 some legal scholars have argued that those who lack that moral core might, at the extreme, be no more responsible for their immorality than those who lack the cognitive ability to perceive the world with sufficient accuracy to allow their reason to guide them through it.76

The law has always recognized that if John kills Miriam by squeezing her neck, but in fact thinks he is squeezing a lemon, he cannot be held legally responsible for her death.77 In fact, in that case John need not prove his insanity as an excusing condition; the prosecution case in chief fails because the prosecution is unable to prove John had the required state of mind, which, as every first year law student learns, is as much an element of most crimes as the acts themselves.

But there is a slightly more complicated, and more common, defect in reasoning that the criminal law recognizes as an excusing condition. Even if a defendant is sufficiently rational to form intentions and act on them, the law still excuses harmful acts if the defendant’s ability to perceive the world is so disabled that it renders his rationality useless to him. This, in short form, is the insanity defense. Daniel M’Naghten was completely rational in the narrowest of senses. If it were true that there was a massive Tory plot to kill him, then his preemptive strike on the Tory prime minister made perfect sense, and he was able to perform step-by-step all the logical acts necessary to accomplish his goal.78 But he still was not legally responsible if in fact his rationality was compromised by a seriously distorted view of the world.

Once we recognize that the key to criminal responsibility is rationality, and a sufficiently rich kind of rationality not only to navigate the perceived world but also to perceive it with reasonable accuracy, then what about psychopaths? They are certainly rational in the narrow sense of being able to determine their best interest and to navigate in the world to achieve that interest. In fact, in some sense they are hyperrational. They consider only their self-interest and they are masters, at least in the short run, of manipulating the world to those interests. But do they perceive the world with sufficient accuracy to be held responsible for their highly rational manipulations of it?

In the end, of course, this is a policy question that requires lawmakers to make a myriad of judgments. On the one hand, it is difficult to justify a system whose entire function is to punish those who incorrectly balance their self-interest against their social duty, if the system is completely insensitive to a whole class of people who do not even own an internal balance. If I am a psychopath, the question is not whether the advantages of a given act under consideration outweigh or otherwise justify the harm I will cause to other people, it is whether I should help myself to what I perceive is a cost-free benefit. Other people are not even on my radar. A psychopath would no more hesitate to rob a victim of $20 than you or I would hesitate to pick up $20 sitting on the sidewalk. The two $20 bills are, in the psychopath’s mind, available for taking in exactly the same way. He does not perceive the interests of the person with rightful possession of the $20 any more than Daniel M’Naghten perceived that his fears of a Tory plot to kill him were delusional.

But the counter arguments are just as powerful. First, of course, the criminal law is a strategic enterprise, and whenever it recognizes exceptions to blameworthiness it can count on people faking the excusing conditions. This has forced the law to recognize only a few narrow exceptions to responsibility—only those that resonate with its original recognition that lunatics, imbeciles, and children are not legally responsible, and even then, more modernly, only when the clinical sciences can speak with at least some degree of reliability about the excusing conditions. If psychiatry, despite all of its waxing and waning efforts and compromises, will still not recognize psychopathy as a formal diagnosis apart from ASPD, you can be sure the law will not recognize it as an excuse.

More significantly, opponents of excusing psychopathy distinguish between Daniel M’Naghten’s delusions about the state of the universe and the psychopath’s claimed lack of free will. The Daniel M’Naghtens of the world—that is, defendants pleading traditional excusing defenses like insanity—rarely claim they were driven to the crime by anything other than their own deluded views of the world.79 M’Naghten did not kill Peel’s secretary because anyone forced him; he voluntarily did so after weighing the options on a seriously deluded scale. Psychopaths are not deluded at all about the external world (except their relative importance in it), and they certainly do not lack free will; their will is in fact too free. Nor can we really say that the psychopath should be excused because his defective moral compass rendered his crimes irresistible to him in the sense of the controversial “irresistible impulse” formulation of insanity. Every person who commits a crime has, by definition, failed to resist committing it.80 And psychopaths seem perfectly capable of resisting self-harming actions that do not require an understanding of the social network. That is, they can resist sticking their hands in a bees nest to get honey, they just cannot resist reaching into another person’s pocket to take money. This is not because they cannot resist in general—though impulsiveness is a part of psychopathy—but because they do not empathize with, or perhaps even recognize, the other person’s relationship to the money.

Perhaps most significantly, how can the system morally punish those of us who on occasion breach the social contract, sometimes for our own gain and sometimes not, but forgive a whole category of criminals who breach it all the time for their own gain? What would a judge say to a defendant about to be sentenced to prison for 10 years for selling crack after sending a serial killer merely to the hospital to cure his psychopathy? Why would we punish those of us whose social scale is sometimes a little out of whack and forgive those whose scale is permanently frozen on “do it”? Law, in the end, is an imperfect accommodation, and, as this argument goes, the system can much better tolerate some moral slippage with an incorrigible 1% of the population than suffer the significant strategic costs a psychopathy defense would cause in the other 99% of cases.

This debate, robust in the academy, has not yet gained the attention of the law, which, with a few tangential and relatively recent exceptions, continues to ignore the psychopath. Psychopathy is not thought of as potentially excusing, and the psychopath’s outrages are mixed in with ordinary, non-psychopathic violations of the social norm. Just as it grossly distorts our recidivism statistics, psychopathy grossly distorts our sense of the extent to which our fellow man is willing to be antisocial. Psychopathy dumbs down the moral integrity of us all, precisely because we do not recognize that so many serious violations are being committed by so few.

The four exceptions to the law’s blind eye to psychopathy—habitual criminal laws, indeterminate sentencing for sex offenders, registration of sex offenders, and special laws on violent sexual predators—are not so much exceptions as coincidences. All these doctrines, to be sure, have a disproportionate impact on psychopaths because psychopaths disproportionately recidivate and disproportionately commit sex crimes. But they are not specifically targeted at psychopaths.

Interestingly, the English have historically treated psychopathy more openly, at least theoretically. For example, English psychopaths who are getting treatment, either as hospital outpatients or as individual psychiatric patients, are specifically excused from jury duty.81 And although the English have been no more willing than anyone else to consider psychopathy as a defense to criminal responsibility, they have, since at least 1983, specifically included psychopathy in the definition of the kind of mental disorder that could be the basis of civil commitment,82 although that express recognition was dropped in 2007.83 Unlike the Americans, whose sexually violent predator statutes were specifically designed to be a continuing complement to the criminal process as defendants are about to be released from prison, the main English commitment statute, at least as it is now being implemented by judges and prosecutors, is generally an alternative to criminal prosecution.84 From the period 1997 through 2007, England committed an average of approximately 26,000 people per year.85 By comparison, roughly one-tenth that number of sex offenders—2,600—were civilly committed in all of the United States in 2006.86 Despite this aggressive English policy of civil commitment generally, and a theoretically more open attitude about psychopathy, the two seem not to have come together. That is, psychopaths in England are not being targeted for civil commitment; they get into the system just like all others do—by committing crimes and then getting diverted to civil commitment.

In any event, it seems problematic at best, and arguably immoral, for any government to hold psychopaths under some claimed medical regimen until their disorder is treated, when the widely held view has been that there is no effective treatment.87 In the end, both the American and English systems seem to have finessed this moral dilemma in slightly different ways. American law has continued to ignore psychopathy, creating the over- and underinclusive category of sexually violent predator to allow the commitment at least of some sexual psychopaths, even after their criminal sentences are completed. The English have been more direct in defining psychopathy as a stand-alone mental condition justifying commitment, but then have backed off as a practical matter in actually committing psychopaths qua psychopaths under their laws.

II. MODERN CLINICAL DEFINITIONS

Despite psychiatry’s continued formal resistance, psychopathy researchers today publish hundreds of articles each year using Hare’s clinical definition of a psychopath. Hare’s assessment includes both the affective and behavioral factors. To qualify as a psychopath under the Hare standards, a subject must exhibit a sufficient number of the Factor 1 and Factor 2 criteria. Those criteria are shown in Table 1.

The Hare instrument requires the clinician to give a score on each of these criteria of 0 (item does not fit), 1 (item fits somewhat) or 2 (item definitely fits). Thus, the minimum score is zero and the maximum 40. Hare himself defined psychopathy as a score of 30 or more, which will exclude most individuals with ASPD unless the subject also exhibits a number of interpersonal and affective traits. Typical group studies break down the Hare scores into the low (20 and below), moderate (21–29) and high (30 and above) ranges. Studies also examine whether the different models of psychopathy88 are related to forensic issues (that is, risk assessment) and neurobiology.

Like all diagnostic criteria for mental disorders, the devil is in the details of the clinical evaluation and in the training of the examining clinicians. Examiners do not ask subjects conclusory questions like, “Are you glib and superficial?” Instead, they ask a series of questions designed to measure glibness and superficiality. The typical Hare evaluation takes between two and six hours, over one or two separate interviews. In addition to this interview time, several of the criteria are established by researching records of the subject’s criminal and incarceration history. The Factor 1, or affective criteria, have been widely documented and analyzed in the context of other mental disorders, but the Factor 2 criteria—the behavioral criteria—warrant further discussion.

It is extremely common for psychopaths to need virtually constant stimulation. They rarely if ever can sit and read, or even sit and watch television. As one might imagine, such a trait does not mix well with the tedium of prison. If things are not happening around them, psychopaths often will make them happen. Their need for stimulation and their impulsivity drive many of the other Factor 2 criteria, including their sexual promiscuity, their inordinate number of marriages, and even their criminal versatility. They are quickly bored with this week’s lover, wife, and type of crime; they move impulsively on to the next, with little appreciation of the meaning of commitment.

Psychopaths are notoriously parasitic. One incarcerated psychopath reported to our investigators that his mom and dad were always supportive, always ready to help him out and always had some money around that he could borrow. But in fact there was a letter in the inmate’s file from his father asking the Department of Corrections to prohibit his son from contacting them. The letter explained that the family, with agony, had decided on this course after 20 years of being deceived and manipulated by their son. They decided they no longer wanted him in their lives. When confronted with this fact, the psychopath laughed and said, “Mom and Dad always say that, but they always give in.”

Anger is never far from the surface in the psychopath. A perplexing aspect of that anger, particularly to the victims, is that the aggression is often over trivialities. A common answer to why a psychopath got so angry over something so insignificant is, “I don’t know, it just pushed my button.”

Psychopathy does not show up unannounced at the door of adulthood. There are always early signs of it, which is why the Factor 2 list includes early behavioral problems and juvenile delinquency among its diagnostic criteria. The typical incarcerated psychopath has a long criminal career stretching back into the juvenile courts, often with serious and violent juvenile adjudications.

Recidivism statistics are discussed at length below,92 but a short vignette may put a more personal touch on the numbers. When the scientist-author was at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, he and his fellow graduate students worked with psychopathic prisoners. One of the prisoner-psychopaths constantly walked around with a car mechanics book under his arm and constantly talked about how he was planning to go to a car mechanics school in the interior of British Columbia when he was released. Coincidentally, on the very morning this man was released, the scientist-author was driving to the prison and saw him, still carrying his car repair manual under his arm, on his way to the bus stop. There were two buses waiting outside the prison—one headed east to his car mechanics school and the other headed west to Vancouver. He looked at both buses, then casually dropped his car repair book in the trash and jumped on the bus to Vancouver. Two weeks later, the scientist-author was doing his rounds at the prison recruiting new volunteers for research when he came across the same inmate. When asked why he was back in prison so quickly, the inmate laughed and said, “Best two weeks of my life.” He had, on the very day of his release, robbed several banks and used the proceeds to rent a penthouse in downtown Vancouver, cavort with prostitutes and buy front row tickets to home hockey games of the Vancouver Canucks. When asked why he did not go to the mechanics school, he looked perplexed and said, comically, “What fun would that be?”

Since Hare’s early grouping of the criteria for psychopathy into just two Factors, other researchers, using a statistical technique called Item Response Theory Analysis, have discovered that there may be utility in further breaking down the two factors into three or four “facets.”93 Researchers are also beginning to develop models that do not assume a given criterion is independent from other criteria, and that instead recognize that having, say, criminal versatility and being a pathological liar may have a multiplying effect, rather than just an additive effect, on the probability of being a psychopath.94 Still, the original PCL-R and its relatives remain the gold standard for diagnosing psychopathy, although these multifactor and nonlinear approaches may end up being even better.

Hare’s approach is not without its critics.95 In addition to continuing skepticism about the clinical reliability of diagnosing and scoring the affective factors, some critics have reprised the whole historical controversy about whether psychopathy is a mental condition or merely a forensic wolf in psychiatric clothing.96 There are also concerns about the predictive ability of the PCL-R in youth and therefore about the propriety of the criminal justice system branding people, especially juveniles, as psychopaths.97

Consequently, we need to move cautiously, but we still need to move. The Hare instruments are reliable enough to be used to identify the most severe psychopaths in the system, both to manage them appropriately and insure that treatment efforts are guided by the best possible practices.98 For example, there is some evidence that traditional group therapy makes psychopaths worse. Since group therapy is so common in prison settings, it will be critical for prison officials to be able to distinguish non-psychopaths, for whom such treatment might be effective, from psychopaths, for whom it might be contraindicated.99 Even more importantly, the instruments should be used to identify youths with psychopathic tendencies who may be amenable to the treatments discussed in Part V below.

III. THE IMPACT OF PSYCHOPATHY ON THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM

The psychopath has had and continues to have a grossly disproportionate impact at virtually every point in the criminal justice system. Though psychopaths make up roughly 1% of the general male adult population, they make up between 15% and 25% of the males incarcerated in North American prison systems.100 That is, psychopaths are 15 to 25 times more likely to commit crimes that land them in prison than non-psychopaths. There is no other variable that is more highly correlated to being in prison than psychopathy. Substance abuse, for example, on which our corrections systems have spent untold trillions, is a distant second. Although between 65% and 85% of people in prison have or had substance abuse problems, 8% of the U.S. population at large suffers from substance abuse.101 Thus, having a substance abuse problem makes it only around nine times more likely that a person will be in prison, compared to psychopathy’s correlation of between 15 and 25 times more likely.

When one looks at violent crimes as opposed to any crime landing a person in prison, psychopathy continues to be impressively predictive. Sixty-two percent of the general male prison population is made up of violent offenders,102 but 78% of imprisoned psychopaths are there because of a violent offense.103 Another chilling statistic: one study found that more than 50% of all police officers killed in the line of duty are killed by psychopaths.104 And although psychopaths and non-psychopaths alike tend to decrease their criminal activity as they get older, this age-related decrease does not appear to apply to psychopaths who commit violent acts, including sexual violence. For psychopaths, their propensity to engage in sexual and nonsexual violence seems to decrease very little with age.105

The correlation between high scores on the Hare scale and prison exists even at scores well below the arbitrary cutoff of 30. All prisoners, psychopathic and not, tend to have much higher scores on the Hare scale than non-incarcerated males, which is not surprising given the tautological nature of some of the Factor 2 criteria. The general nonprison population scores a median of 6.6 on the Hare scale, while the average score by a North American inmate is 22.1.106 And it is not the case that large numbers of prisoners at the high end are skewing that average; psychopathy scores are normally distributed.

After a psychopath has been sentenced to prison but before the adult system labels him incorrigible, data suggests that he is more likely to be released early than his non-psychopathic cohorts despite a typically long and uninterrupted juvenile record. In a study published in January 2009, Stephen Porter and his colleagues examined the files of 310 male offenders serving at least two years in a Canadian prison between 1995 and 1997.107 Ninety were determined, retrospectively, to be psychopaths.108 Porter found that the psychopaths were roughly 2.5 times more likely to be conditionally released than non-psychopaths.109 Psychopathy was only a slightly less-effective predictor of the early release of sex offenders, psychopathic sex offenders being released 2.43 times more frequently than non-psychopathic sex offenders.110 Porter suggests these results may be because the psychopath is able to use his finely honed skills of deception and manipulation to convince prison officials to release him early.111 It seems prison mental health experts and parole boards are no less immune than the rest of us to being fooled by the psychopath’s mask of sanity.

A. Recidivism

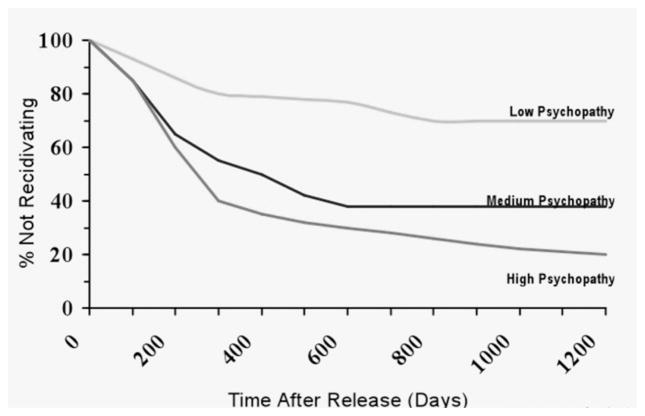

Once released, psychopaths are much more likely to recidivate than non-psychopaths. Canadian studies have been most instructive on this issue because the Canadian federal government keeps national recidivism statistics. In a 1988 study, Canadian researchers identified a group of 231 prisoners about to be released, gave them all clinical assessments for psychopathy using the Hare instrument, divided them into low, moderate and high categories of psychopathy based on their Hare score, and then followed them for three years.112 After only nine months, more than half the high psychopaths had not only been rearrested but reconvicted, as seen in Figure 3. By the end of three years, the individuals with high psychopathy scores bottomed out at approximately an 80% recidivism rate. By comparison, only approximately 15% of the individuals low on psychopathic traits had been reconvicted at the nine-month mark, and only approximately 30% had been reconvicted at the end of the three years.

Figure 3.

Recidivism Among Psychopaths113

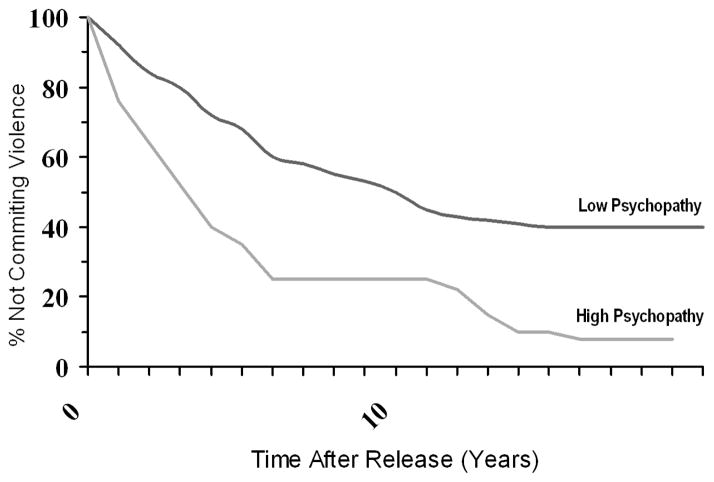

The recidivism patterns are similar if we look only at violent recidivism (Figure 4) or, even more narrowly, violent sexual recidivism (Figure 5). Both of these sets of data come from Rice and Harris’ 1997 retrospective study of 288 convicted sex offenders, covering 20 years of violence and 10 years of sexual violence.114 Notice that even within the very first year after release a whopping 25% of all individuals scoring high in psychopathy were rearrested for a new violent offense, and that after seven years only 25% had not been rearrested for a new violent offense. By the study’s 20-year end, individuals high in psychopathy had a violent recidivism rate of 90%, compared with 40% for individuals scoring low in psychopathy (as shown in Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Violent Recidivism Among Psychopaths115

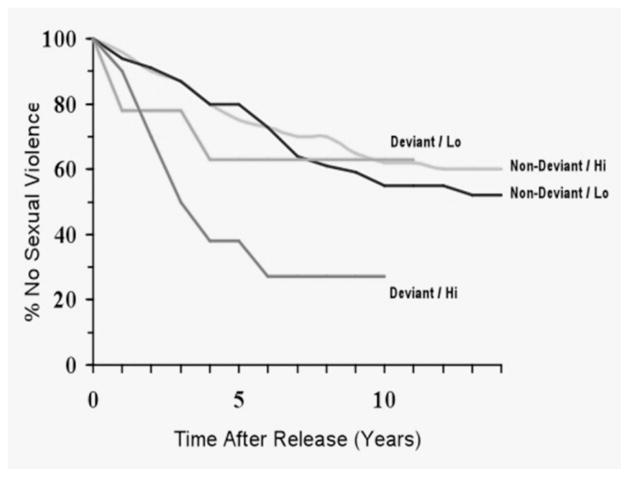

Figure 5.

Violent Sexual Recidivism Among Psychopaths116

The picture is almost as bad for violent sexual recidivism. Psychopathy is a significant predictor of sexual violence. Rice and Harris found that 75% of all individuals with both a high Hare score and a positive sexual deviance response—defined as a positive penile pleithismograph response to depictions of children, rape cues, or nonsexual violence—committed a new sexually violent crime within 10 years (as shown in Figure 5).

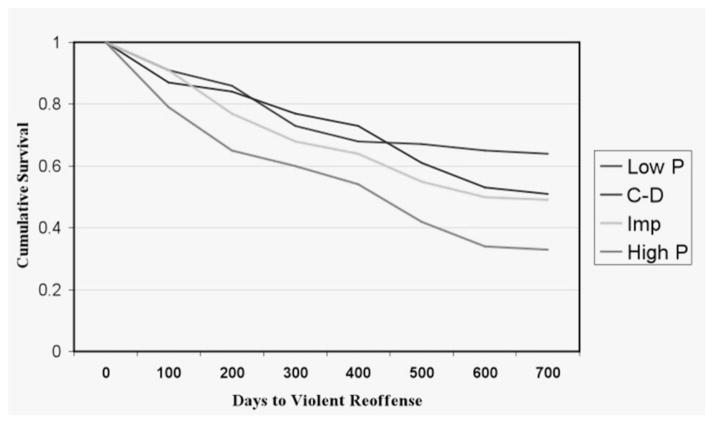

Psychopathic traits in youths have also been shown to predict high recidivism. Figure 6 shows the results from a study by Vincent et al., demonstrating that youth who have both callous-unemotional traits and impulsive traits are at a higher risk for being convicted of a new violent crime.117

Figure 6.

Violent Recidivism Juvenile Offenders118

The bottom line is that psychopaths, who represent roughly 20% of the prison population, recidivate at massively higher rates, and more quickly, than the other 80%. The average psychopath is back and forth to prison three times before the average non-psychopath with the same sentence makes it back once.119 The average incarcerated psychopath has been convicted of committing four violent offenses before age 40.120 While the typical non-psychopathic felon may ponder and struggle with life on the outside and with changing his criminal ways, the typical psychopath returns to his life of crime, and often violent and sexual crime, in the same way he does everything—impulsively, selfishly and without any regard to the rights of others, rights he does not even notice.

B. The Costs of Recidivism by Psychopaths

Many of the following statistics will be familiar to readers steeped in the public policy of crime control; they are visited here in an attempt to tease out the costs associated only with psychopathy. One oft-cited study estimates that crime’s overall cost to U.S. society—in direct economic costs such as lost property, and in indirect costs for police, courts, prosecutors, public defenders, jurors and, most significantly, jails and prisons—is on the order of $2.3 trillion per year in 2009 dollars.121 If we assume 20% of the males in prison are psychopaths and that a similar percentage is involved in nonfelony offenses, and if we ignore the relatively small contributions of women offenders to this overall number, psychopaths alone are responsible for approximately $460 billion per year in criminal social costs.122 Note that this $460 billion number does not include the costs of the psychopath’s similar overrepresentation in psychiatric hospitals. Nor does it include indirect costs such as treatment for victims and their nonquantifiable emotional suffering because Anderson’s original number did not include these types of costs.

How do the social costs of other conditions high in the public consciousness compare with the criminal costs of psychopathy? They all pale in comparison. The annual societal cost of alcohol-substance abuse is estimated to be $329 billion,123 obesity $200 billion,124 smoking $172 billion,125 and schizophrenia $76 billion.126 And each of these numbers, unlike our $460 billion for psychopathy, include other institutional costs besides the criminal justice system, primarily hospitalization and treatment, though none includes any costs suffered by the victims.

Given the grossly disproportionate contribution that psychopaths make to the exploding costs of our criminal justice and correctional systems, one might expect that criminologists and corrections officials would be very interested in reducing the recidivism of psychopaths. Alas, psychopath being a synonym for incorrigible, psychopaths have been not been the objects of sustained treatment efforts either in or out of prison. Given the neuroscience and therapeutic discoveries discussed in the next two sections, perhaps this neglect may soon come to an end.

IV. THE NEUROSCIENCE OF PSYCHOPATHY

Psychopathy has been just as elusive to neuroscientists as to everyone else, and for the same reasons. Much work has been done identifying the neurobiology of violence, showing a strong genetic component127 as well as a robust interaction between early childhood trauma to the frontal lobes and the emotional effects of abuse.128 But of course violence is much too large a behavioral slice to get at psychopathy. As one neuroscientist writing about psychopathy has said:

When we attempt to focus on the psychopath, we find various difficulties. Most large-scale studies are based on behaviors (childhood aggression, criminal arrests, etc.) with only rare reference to the specific diagnosis of the violent subjects. This point is crucial, as the majority of aggressive individuals or even convicted criminals are not psychopaths, even though committing criminal acts is needed to fulfill definitions for either antisocial personality disorder or psychopathy.129

Psychopaths’ lack of moral cognition, as well as the studies showing trauma to the frontal regions being associated with aggression, led early researchers to surmise that psychopathy may be rooted in defects to the frontal cortex, areas generally associated with higher order functions like reasoning and executive control. For example, Antonio Damasio and his colleagues published anecdotal cases of lesions to the inferior and medial surfaces of the frontal lobes that produced apparent psychopathic behaviors.130 Adrian Raine and his colleagues showed by structural MRI that at least unsuccessful psychopaths—those who get caught—have reduced gray matter, fewer neurons, and increased white matter (that is, more connections between neurons) in the frontal lobes.131 The reduced gray matter suggests damage causing neural atrophy, and the increased white matter is consistent with some kind of defect in the pruning away of white matter that ordinarily happens in the development of the growing brain.

But even as late as the 1990s, the neurological hallmarks of psychopathy remained unclear, and there were no hallmarks that came close to being reliable enough to be diagnostic. Moreover, the hypothesis that psychopathy was generally a reflection of reduced frontal lobe activity seemed to conflict with a long-standing series of studies that began in the 1940s showing that psychopaths in fact have greater than normal frontal EEG signals, both waking and sleeping.132 It took the use of fMRI to begin to unlock the neurological mysteries of psychopathy because the way in which the brain of the psychopath interacts with other humans beings, or actually fails to interact, is psychopathy’s essential feature. Static images of brain morphology tell only the tiniest part of the story. Seeing brains functioning as they navigate social problems has shown us, with remarkable reliability, that psychopathic brains cannot navigate those problems.

Functional MRI or fMRI is a technique that was developed in the early 1990s by Kwong et al.133 It detects and then maps changes in blood oxygenation in the brain. Like muscles, neurons consume oxygen when they are working. The MRI can be tuned to locate regions in the brain where oxygen is being recruited. In a typical fMRI study, researchers present subjects with stimuli—videos, pictures, sounds or words—while the subjects are lying in the MRI scanner. The regions of the brain that are engaged with processing the given stimuli are mapped, and brains faced with the stimuli are compared with brains at a resting state. FMRI involves many technical and statistical processes, and significant training is required to understand its strengths, weaknesses and limitations. Nevertheless, fMRI provides an unprecedented opportunity to study clinical disorders in general and psychopathy in particular.

In 2001, the first study to use fMRI to study the brains of criminal psychopaths was published; this study is discussed in detail below.134 But this and other fMRI studies were hobbled to some extent by small sample sizes. It is difficult to find psychopaths and expensive and time-consuming to administer the Hare instruments to them. Statistically, one of the best places to find psychopaths is in prisons. But prisons typically have no MRI equipment, so early investigators had to transport psychopathic prisoners to and from prisons to local hospitals. The logistics, cost, and security issues associated with such arrangements kept the subject numbers on these studies low.

In 2007, with grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Mental Health, the United States Department of Energy and the State of New Mexico, the scientist-author designed and purchased the first-ever mobile fMRI system. In collaboration with the New Mexico Corrections Department that equipment is brought to the prisoners rather than the other way around. In the first three years of deployment, more than 1,100 inmates volunteered to participate in fMRI studies. This collection of brain scans is the largest forensic brain imaging database in the world.

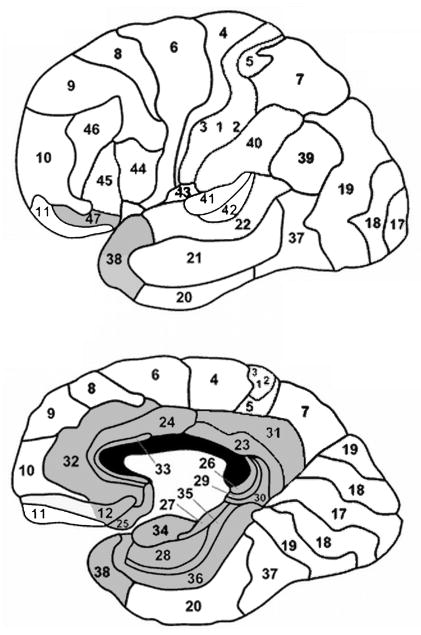

The fMRI data shows a robust and persistent pattern of abnormal brain function in psychopaths: namely, decreased neural activity in the paralimbic regions of the brain. These are the regions generally below the neocortex, including and adjacent to the limbic structures, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The Paralimbic System135

The paralimbic regions form a kind of girdle surrounding the medial and basal aspects of the two hemispheres. They contain many important structures, including the anterior temporal cortex, ventromedial prefrontal cortex, amygdala, insula, temporal pole and cingulate, many of which are associated with moral reasoning, affective memory and inhibition, exactly the kinds of puzzle pieces one would expect might be involved in psychopathy.136 The fMRI experiments were aimed at exploring these and other affective and cognitive processes as they relate to psychopathy.

In the moral reasoning task, 72 incarcerated subjects, of whom 16 were psychopaths with Hare scores of 30 or greater, were shown a series of pictures and asked to rate them on a scale of 1 to 5 for moral violation, 1 being no moral violation and 5 being severe moral violation.137 Some pictures had obvious moral content, such as a KKK cross burning, others were ambiguous, and still others had no moral content at all. Behaviorally there was no significant difference between the ability of psychopaths and non-psychopaths to recognize the moral content of these scenarios.138 But the neurological story was very different. Compared with non-psychopaths, psychopaths showed decreased activation in the right posterior temporal cortex and increased activation in the amygdala, two areas well known to be associated with moral reasoning.139 See Figure 8.140

Figure 8.

Moral Decision Making in Psychopaths143

A simple word recognition test was used for the affective memory study.141 Participants were shown a series of 10 words for two seconds each and asked to try to remember as many as possible. They then were shown additional lists of words and asked whether the additional words were on the original memorized list. Different word lists are presented over the course of the study. Some of the words on the lists were negative in affective content (words including misery, blood, frown, scar, wreck) and some neutral (words including gallon, oat, brass, card). It is well established that unimpaired people are better at remembering words that have an emotional content than they are at remembering words with no emotional content. Researchers have also known for some time that psychopaths remember emotional words just as well as non-psychopaths do, even though it takes psychopaths longer to recognize the emotional content of the words.142 That is, to the extent short-term memory is some measure of whether the affective content of words is actually getting into the brains of psychopaths, it appears the answer is yes. But this study showed those memories seem to take a very different path in psychopathic brains than they do in non-psychopathic brains.

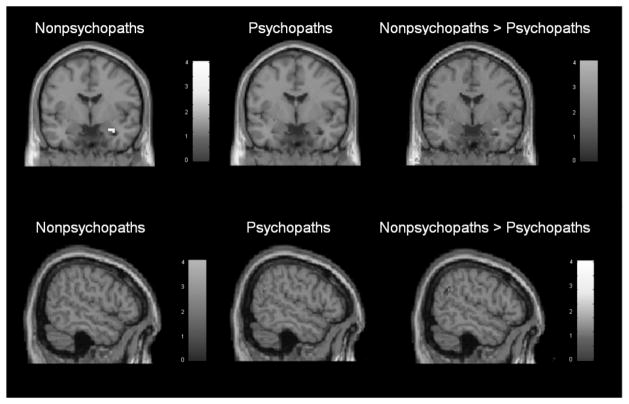

Prisoner-psychopaths showed greatly reduced activations in the amygdala and posterior cingulate, somewhat reduced activations in the ventral striatum and anterior cingulate, and greatly increased activation in the frontal gyrus. That is, they showed reduced activity in paralimbic regions—amygdala, anterior and posterior cingulate—and increased activity in the lateral frontal cortex, an area typically associated with cognition, not emotion. See Figure 9.

Figure 9.

The fMRI of an Affective Memory Task in Criminal Pyschopaths

The figure shows the rendering of the neural areas in which criminal psychopaths showed significantly less affect-related activity than noncriminal control subjects for the comparison of affective words versus neutral words of an affective memory task.144 Regions include (top left) posterior cingulate, caudal and rostral anterior cingulate, and ventral striatum (top right), right amygdala-hippocampus. Also shown are the regions in which criminal psychopaths showed greater affect-related activity than noncriminal control subjects and criminal non-psychopaths (bottom panels; depicted in gray scale; see Kiehl et al., Limbic Abnormalities, for a color reproduction of the figure). These regions include bilateral inferior frontal gyrus.145

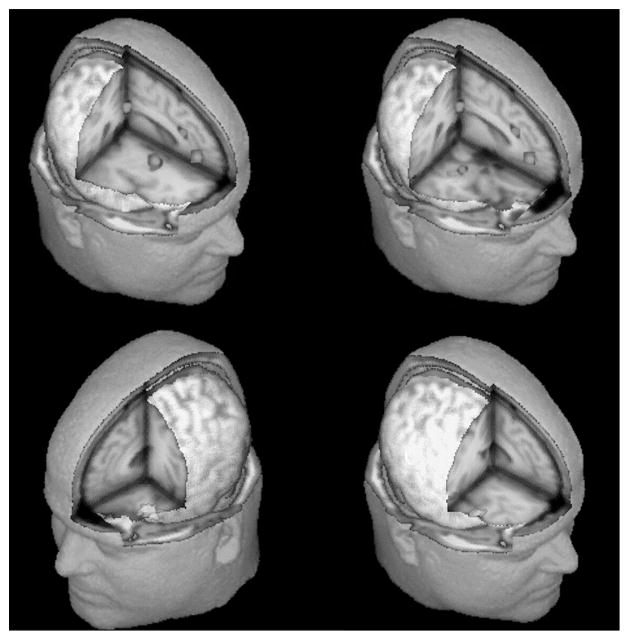

To study inhibition, we used a common “go-no-go” paradigm. Subjects are shown one of two letters in rapid succession (50 ms), in this case ether an “X” or a “K,” and instructed to press a button every time an “X” appears, but not to press the button when a “K” appears. When a subject correctly inhibits a response to the “K” stimulus, it is called response inhibition. It is well known that psychopaths perform significantly worse than non-psychopaths in the go-no-go task; that is, psychopaths are much less likely to inhibit their responses when the “K” shows up.146 This inability may explain the psychopath’s poor behavioral controls, nomadicity, and generally impulsive lifestyle.

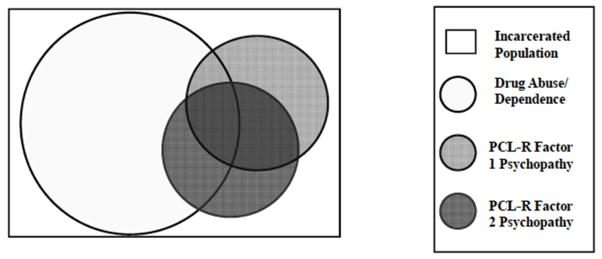

In turns out that the regions of the brain involved in inhibition overlap the paralimbic regions, primarily the anterior and posterior cingulate. The go-no-go task was administered in the mobile scanner, looking for brain differences that might explain the psychopath’s reduced response inhibition. Both adults and juveniles high in psychopathic traits exhibited dramatically decreased activity in these inhibitory regions.147 See Figure 10.

Figure 10.

The fMRI Results for Response Inhibition Task148

Putting these results together begins to paint a picture of the psychopathic brain as being markedly deficient in neural areas critical for three aspects of moral judgment: 1) the ability to recognize moral issues; 2) the ability to inhibit a response pending resolution of the moral issue; and 3) the ability to reach a decision about the moral issue. Along with several other researchers,149 we have demonstrated that each of these tasks recruits areas in the paralimbic system, and that those precise areas are the ones in which psychopaths have markedly reduced neural activity compared with non-psychopaths.

What does all this mean? First, it suggests that the story of psychopathy is largely limbic and paralimbic rather than prefrontal.150 This dovetails nicely with the central paradox of the psychopath: he is completely rational but morally insane. He is missing the moral core, a core that appears intimately involved with the paralimbic regions. If the key to psychopathy lies in these lower regions, then it is no mystery that the psychopath is able to recruit his higher functions to navigate the world. In fact, when he gives a moral response, it seems the psychopath must recruit frontal areas to mimic his dysfunctional paralimbic areas. That is, the psychopath must think about right and wrong while the rest of us feel it. He knows morality’s words but not its music.

Second, these neurological results should go a long way toward ending the debate about whether psychopathy is just too difficult to diagnose to justify inclusion in the DSM. Any lingering doubts about the clinical reliability of the Hare instruments disappear now that those instruments have been shown to be robustly predictive of a demonstrable neurological condition.

Third, and perhaps more significantly, these imaging techniques may help us identify and then understand the development of psychopathic traits in juveniles. It is difficult, and controversial, to assess psychopathic traits in young people. No one wants the label psychopath to become self-fulfilling, especially given the hopeful treatment possibilities discussed in Part V. Brain imaging may help us improve our understanding of the developmental trajectories of these traits in ways that might improve treatment.

Still, caution is in order. Neuroimaging has its own embedded limitations, making the reliability of conclusions based on imaging data a complex and still developing story.151 Those conclusions about psychopathy are especially preliminary, given the still relatively small numbers of scanned psychopaths, and questions remain about the specificity of these apparent paralimbic defects, their origins, their stability over lifespan, and their diagnostic utility.

One also might argue that these results support the position that psychopathy should be an excusing condition.152 But this debate is not really an empirical one. We have known forever that psychopaths are rational yet persistently immoral. The results of the neuroimaging study confirm that, but the studies cannot answer the policy question of whether the psychopath’s lack of moral recognition machinery is the kind of disorder that should be excused.

V. THE TREATMENT OF PSYCHOPATHY

The received dogma has been that psychopathy is untreatable, based on study after study that seemed to show that the behaviors of psychopaths could not be improved by any traditional, or even nontraditional, forms of therapy. Nothing seems to have worked—psychoanalysis, group therapy, client-centered therapy, psychodrama, psychosurgery, electroshock therapy or drug therapy153—creating a largely unshakable belief among most clinicians and academics, and certainly among lay people, that psychopathy is untreatable, though as we will discuss below few if any of these studies were properly controlled and designed.

Most talking therapies, at least, are aimed at patients who know, at one level or another, that they need help. Psychotherapy normally requires patients to participate actively in their own recovery. But psychopaths are not distressed; they typically do not feel they have any psychological or emotional problems, and are not only generally satisfied with themselves but see themselves as superior beings in a world of inferior ones. Clinicians report that psychopaths go through the therapeutic motions and are incapable of the emotional insights on which most talking therapy depends. As one psychotherapist wrote, his psychopaths in treatment “have no desire to change, … have no concept of the future, resent all authorities (including therapists), view the patient role as … being in a position of inferiority, and deem therapy a joke and therapists as objects to be conned, threatened, seduced, or used.”154 More direct forms of therapy—surgery, electroshock, drugs—are shots in the dark. No one yet knows how to restore the paralimbic functions that seem so impaired in psychopathy.

Treatment not only seems not to work, there is evidence that some kinds of treatment make matters worse. In a famous 1991 study of incarcerated psychopaths about to be released from a therapeutic community, those who received group therapy actually had a higher violent recidivism rate than those who were not treated at all.155 One explanation is that being exposed to the frailties of normal people in group therapeutic settings gives psychopaths a stock of information that makes them better at manipulating those normal people. As one psychopath put it, “These programs are like a finishing school. They teach you how to put the squeeze on people.”156 Group therapy is also, of course, an endless source of excuses—my parents didn’t love me, I was abused, my wife left me, I am numb and empty inside, I am useless—none of which the psychopath actually feels but all of which he can use to his tactical advantage at the right moments, especially when trying to manipulate mental health professionals.

But all treatment hope for psychopaths is not lost. Like many mental health treatment efforts, prior efforts to treat psychopaths, as well intentioned and numerous as they have been, have almost never been designed to meet acceptable scientific and methodological standards. Indeed, most treatment “data” has been little more than an amalgamation of clinical anecdotes, and most of the large efforts that have been attempted have been poorly designed and controlled. Even the better studies typically involved moderate rather than intense treatment, and over relatively short durations. And of course one of the self-defeating aspects of these studies is that the psychopaths themselves often become disruptive in therapeutic settings not designed to deal with such levels of disruption. The state of the treatment literature has been described as “appalling.”157

The good news about all this bad science is that maybe something does, in fact, work. There may be some room for some thoughtful, targeted, well-designed, and controlled treatment efforts—efforts that might even prove effective, especially with juveniles. In a landmark 1998 metastudy focused on the treatment of juveniles with psychopathic tendencies,158 Mark Lipsey and David Wilson concluded that, although the reported treatment outcomes were not encouraging, pieces of many different studies might be.159 And although their metastudy did not deal expressly with juveniles, it was clear that large segments of the subjects covered by the studies were in fact juveniles.

Inspired by Lipsey and Wilson, Michael Caldwell and his colleagues at the Mendota Juvenile Treatment Center in Madison, Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin, reviewed the treatment literature in detail, noticed all of its failings and promises, and decided to design a specific treatment program for psychopathic juvenile offenders. They unashamedly borrowed from a smorgasbord of treatment theories and practices, precise descriptions of which are not important here, except to say that they label their resulting program “decompression treatment.”160 The bottom line is that the treatment program they designed is intense, requiring several hours per day, long lasting (a minimum of six months and sometimes even exceeding one year), one on one, and focused on the slow and methodical rebuilding of the social connections that are absent in psychopaths.

Early results were encouraging. In a 2001 pilot study of violent juvenile offenders, Caldwell and his colleagues divided 30 of them into three groups of 10—one control group received no therapy, the other control group received traditional group therapy, and one group received Caldwell’s decompression therapy.161 The study followed the juveniles for two years, and the recidivism results were promising: 70% of the control group receiving no treatment was rearrested at least once in the two years, 20% of the group getting traditional group therapy treatment, and only 10% of the group getting Caldwell’s decompression treatment.162 These results were encouraging on two fronts. First, contrary to the earlier study showing that traditional group treatment of adult psychopaths could make them worse,163 Caldwell’s initial results with juveniles showed a significant improvement even with traditional group therapy. Even more encouraging, Caldwell’s decompression therapy was twice as good as the already good traditional therapy. This pilot study suggested that Lipsey and Wilson might be right—that treatment might work if juvenile psychopaths are treated early enough, intensely enough and for long enough. But of course the numbers, though promising, were extremely small.

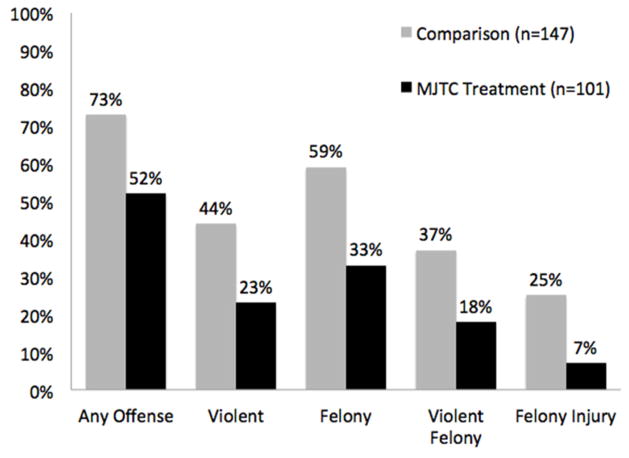

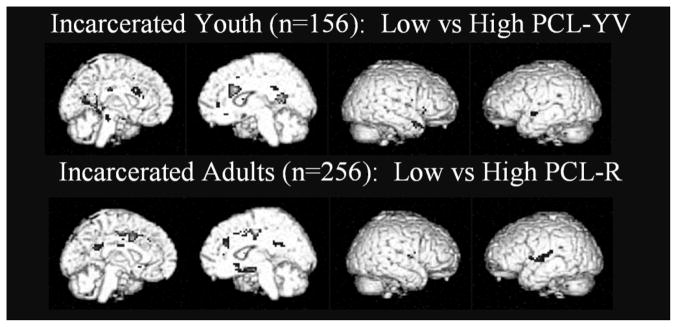

Caldwell and his colleagues subsequently conducted a larger follow-up study.164 This time, they followed 248 incarcerated boys, all of whom had been labeled unmanageable, for an average follow-up period of 54 months.165 Approximately 40 percent (101) received the decompression therapy, 60 percent traditional group therapy.166 The recidivism results showed a significant decrease for those who got the decompression therapy (56% versus 78%), and this included the category of violent recidivism (18% versus 36%).167 The results are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Two Year Follow-Up of Youth Treatment Study170

In the latest published study, Caldwell and his colleagues followed 86 maximum security juvenile offenders in the Mendota center, and again looked at arrest recidivism, this time four years out.168 The researchers also assessed each subject initially for psychopathy, using the Hare instrument for juvenile psychopaths, the PCL-YV.169 Over time, the PCL-YV scores were retaken, as was a measure of institutional misconduct called security days (SD), as was rearrest data. All of these quantitative measures were analyzed and correlated. Caldwell and his group reached several conclusions.

First, as expected, the PCL-YV scores were high (mean = 30.2), and were highly correlated both to recidivism and to institutional misconduct. Second, and most importantly, the decompression treatment was highly effective in reducing both institutional misconduct and recidivism, but only if it was lengthy and only—and here is the less promising aspect of the study—for juveniles scoring in the low to moderate ranges of the PCL-YV (≤ 31). The best predictor of reductions in institutional misconduct and recidivism was the length of the decompression treatment. Short-term treatment seemed to have no effect. But long-term treatment, lasting up to and beyond one year, significantly reduced both institutional misconduct and recidivism, at least for the subjects scoring 31 and less on the Hare instruments.