Abstract

Astrocytes, the most abundant cell population in the central nervous system (CNS), are essential for normal neurological function. We show that astrocytes are allocated to spatial domains in mouse spinal cord and brain in accordance with their embryonic sites of origin in the ventricular zone. These domains remain stable throughout life without evidence of secondary tangential migration, even after acute CNS injury. Domain-specific depletion of astrocytes in ventral spinal cord resulted in abnormal motor neuron synaptogenesis, which was not rescued by immigration of astrocytes from adjoining regions. Our findings demonstrate that region-restricted astrocyte allocation is a general CNS phenomenon and reveal intrinsic limitations of the astroglial response to injury.

Astrocytes serve roles essential for normal neurological function such as regulation of synapse formation, maintenance of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and neuronal ho-meostasis (1, 2). Although astroglia are regionally heterogeneous in terms of gene expression and their electrical and functional properties (3–5), astrocyte diversification and migration remain poorly understood. Two generally recognized types of astrocytes are fibrous astrocytes (FAs) of white matter that express glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and protoplasmic astro-cytes (PAs) of gray matter that normally express little or no GFAP. Aldh1L1-GFP and AldoC are more recently described markers of both PAs and FAs (6, 7). Embryonic astrocytes derive from radial glia (8–10) and several lines of evidence indicate that glial subtype specification in the ventral spinal cord is determined according to a segmental template (11). For example, basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins Olig2 and SCL regulate oligodendrocyte versus astrocyte precursor cell fate in the pMN and p2 neuroepithelial progenitor domains, respectively (12), and homeo-domain proteins Nkx6.1 and Pax6 regulate the region-specific molecular phenotype of FAs in the ventral spinal cord (13).

How do astrocytes disseminate from their sites of origin in the ventricular zone (VZ)? Two distinct modes of astrocyte migration have been reported. Retroviral fate mapping of neonatal SVZ progenitors (14) and transplantation of glial precursors (15) suggest that astrocytes can migrate long distances and in multiple directions, implying that astrocytes derived from radial glia (or other precursors) in different VZ domains might intermix (fig. S1A). Consistent with this model, some PAs have been proposed to derive from migratory NG2 cells (16). In contrast, as-trocytes might distribute stringently into “segmental” territories correlating with their domains of origin in the patterned VZ (8–10), without secondary tangential migration. Although little is known about regulation of astrocyte progenitor migration during development, Stat3 signaling and Cdc42 have been shown to function in reactive astrocyte invasion of lesions after injury (17, 18).

Establishing how astrocytes are allocated to different territories is key to understanding how they might develop to support regionally diversified neurons. We first investigated this in vivo by conditional reporter fate mapping of radial glia and their progeny in distinct dorsal-ventral (DV) spinal cord domains (fig. S1B and table S2). Labeling for the reporter protein together with markers of neurons (NeuN), oligodendro-cytes (Olig2), or fibrous astrocytes (GFAP) allowed us to compare production of these cell types across domains (table S1, Fig. 1, and fig. S1) (19).

Fig. 1.

Segmental distribution of fibrous and protoplasmic astrocytes in spinal cord. (A) Nkx2.2-creERT2 (tamoxifen induction E10.5 to E12.5):Rosa26-YFP fate map shows YFP+, GFAP+ cells at the ventral mid-line at P0. YFP, yellow fluorescent protein. (B) In P2 Olig2-tva-cre:CAG-GFP mice, astrocytes remain in register with pMN, whereas Olig2+ OPs distribute widely. (C) Ngn3-cre:Z/EG P1 cord shows intermediate wedge of astrocytes. (D, G, G′) At P2, FAs and PAs in Pax3-cre animals remain dorsally restricted. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. (E and F) Aldh1L1-GFP coexpression with GFAP+ (FAs) and AldoC+ (FAs and PAs) cells. (H to N) Astrocytes from Olig2cre/+ spinal cord have a restricted ventral distribution. In Olig2cre/cre nulls, we observe significantly (*P < 0.0001) increased p2-type (GFAP+, Pax6+, AldoC+) astrocytes (fig. S1I), which fail to migrate from the ventral domain. Scale bars, 200 μm.

We found that FAs from the p3 progenitor domain (defined by Nkx2.2-creERT2) invariably remained close to the ventral midline (Fig. 1A). The pMN domain (Olig2-tva-cre) generated mainly oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPs), which migrated extensively (Fig. 1, B and H), and some FAs [4% of all GFP+ cells in spinal cord at post-natal day 7 (P7)] (fig. S1D and table S1) (20), which settled in ventral white matter (Fig. 1B). For intermediate and dorsal domains, we used cre driven by Ngn3, Dbx1, Msx3, Math1, or Pax3 regulatory sequences (Fig. 1, C and D; table S1; and fig. S1, E to H). These data indicate that all spinal cord GFAP+ FAs distribute radially, in register with the DV position of their neuro-epithelial precursors.

PAs and FAs are morphologically and functionally distinct (21, 22). We used Aldh1L1-GFP astrocyte-specific reporter mice (7) and antibodies recognizing AldoC (6), which mark both PAs and FAs but few, if any, neurons or Olig2+ cells (Fig. 1, E and F; figs. S2E and S3, A and B; and movie S1). Fate mapping of BLBP-cre expressing precursors (fig. S3, C and D) demonstrated that PA and FA are generated from radial glia and/or their progeny. PAs and FAs originating from the same precursor domain came to rest within overlapping territories. For example, combining Pax3-cre with the Aldh1L1-GFP reporter confirmed that all Pax3-derived PAs and FAs remained confined to dorsal spinal cord (Fig. 1G). Despite reports that FAs and PAs develop via distinct pathways (16, 23, 24), we did not observe any domain dedicated to either FAs or PAs.

We next attempted to disrupt the radial distribution of astrocytes. First, because embryonic pMN-derived OPs disperse in all directions (Fig. 1I) (25), we tested whether this domain might similarly promote tangential astrocyte migration. In Olig2-null embryos, the pMN domain is transformed into a p2-like domain that generates astrocytes instead of OPs (26). In the embryonic day 18 (E18) Olig2-cre-null spinal cord, we found increased numbers of “p2-type” astrocytes (fig. S1I) but, nonetheless, these remained spatially constrained within the ventral cord (Fig. 1, I to N). Although all domains examined produced as-trocytes, they showed different potential for the generation of astrocytes versus oligodendrocytes (fig. S1J), most dramatically illustrated by Olig2-null animals. Time-lapse imaging of spinal cord slice cultures revealed exclusively radial movement of Aldh1L1-GFP cells (fig. S3, E and F), even after a heterotopic transfer of green fluorescent protein (GFP)–labeled VZ progenitors into unlabeled slices (fig. S3, G to K). Together, these data reveal a strictly segmental investment of the developing spinal cord by astrocytes (fig. S1A).

Might astrocytes undergo secondary tangential migration at later stages or during adulthood? Ngn3 transcripts are transiently expressed in intermediate neural tube from E12.5 to E14.5 (fig. S2, A to D). As shown (Fig. 2A and fig. S2, E and F), intermediate-domain PAs derived from embryonic Ngn3-cre–labeled radial glia persisted up to 6 months without attrition or migration. We induced Nkx2.2-creERT2:Rosa26-YFP mice with tamoxifen (E10 to E12, after generation of p3-derived neurons) and visualized the labeled astrocytes 1 year later (Fig. 2B). Even at this advanced age, FAs and PAs were confined in a tight ventromedial distribution. These findings show that the long-term distribution of astrocytes in the adult spinal cord is determined during embryogenesis by their site of origin in the VZ (fig. S2G).

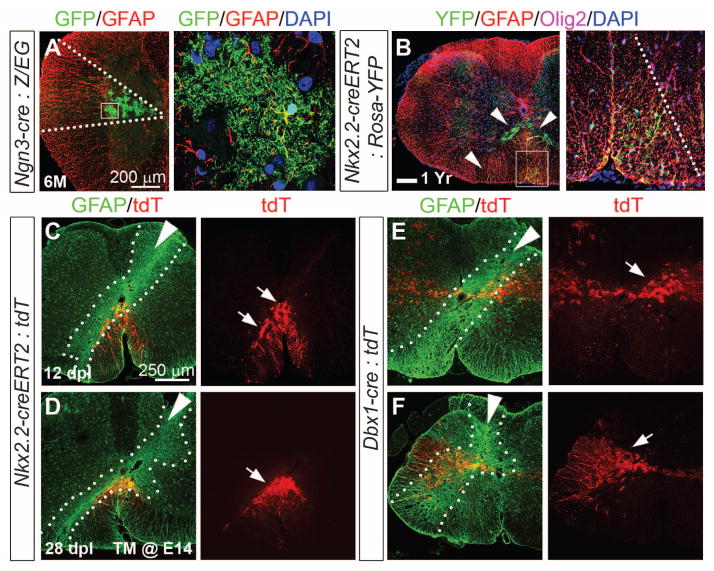

Fig. 2.

Absence of tangential astrocyte migration in adult spinal cord even after injury. (A) Bushy GFP+ PAs in Ngn3-cre:Z/EG cord persisted after 6 months of age. (B) Astrocytes in Nkx2.2-creERT2 (induced E10 to E11):Rosa26-YFP cords remain ventrally restricted at 1 year. (C to F) Post-stab gliosis does not recruit astrocytes from adjacent domains. Fate-mapped astrocytes (arrows) in Rosa26-tdTomato on the Nkx2.2-creERT2 [induced E14 (C and D)] or Dbx1-cre (E and F) background remain confined to ventral or intermediate cord, respectively, 12 and 28 days postlesion (dpl). Intense GFAP staining indicates lesion site (dashed lines, white arrowheads indicate needle trajectory).

We attempted to disrupt the normal “segmental” pattern of astrocytes by acute injury-induced gliosis in adult Rosa26-tdTomato conditional reporters crossed into Nkx2.2-creERT2 (induced at E14) or Dbx1-cre backgrounds. However, no ventrally derived astrocytes migrated into a dorsal stab wound after 12 or 28 days, despite the lesion tract passing very close to the labeled astro-cytes (Fig. 2, C to F).

A possible explanation for the lack of mobility was that all astrocyte niches were fully occupied, preventing immigration from other domains. Previously, we achieved selective elimination of OPs using Diphtheria toxin A (DTA) under Sox10 transcriptional control (27). We generated an analogous Aldh1L1-based system in which the nonrecombined transgene expresses eGFP, whereas cre exposure deletes eGFP and promotes DTA expression (Fig. 3A). Intercrosses with Pax3-cre mice resulted in perinatal lethality (10% survivors observed versus 25% expected). The dorsal spinal cord (corresponding to the Pax3 domain) of P25 animals showed atrophy, reduction in the total number of Aldh1L1-expressing cells, loss of neuropil, and congested neurons (Fig. 3, C and D, and fig. S4A). We did not observe increased inflammation, gliosis, or BBB permeability in these mice (fig. S4, A and C), suggesting that remaining astrocytes were sufficient for structural maintenance. Although ventral astrocytes might have invaded to rescue the dorsal cord, this possibility was ruled out because they would have continued to express GFP. The mild phenotype of Pax3-cre:Aldh1L1-DTA animals suggested astrocyte depletion rather than ablation. We quantified astrocyte depletion by crossing Aldh1L1-DTAwith BLBP-cre, active in radial glia. Double-transgenics died at birth, but at E17.5 we observed 43% excision of transgene GFP and a 28% reduction in AldoC+ astrocytes (fig. S4B). It is possible that some astrocytes survived because they are resistant to attenuated DTA (27); alternatively, expression of our trans-gene might be variegated.

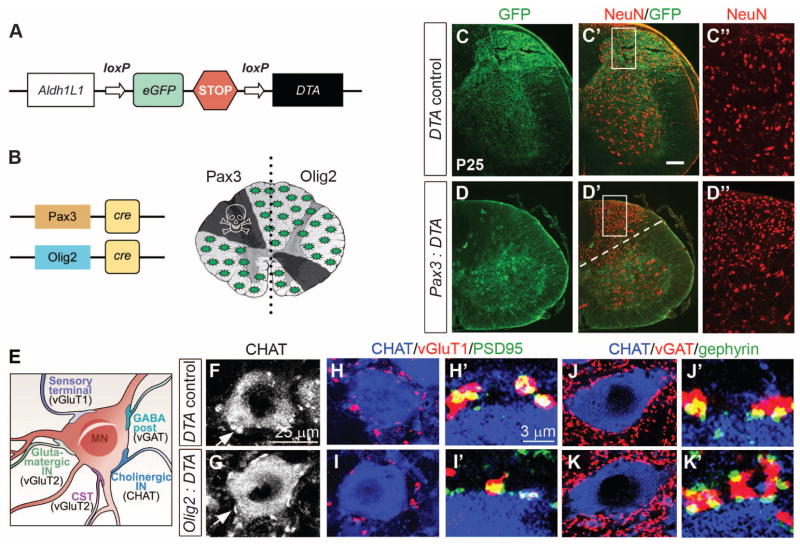

Fig. 3.

Regional astrocyte depletion results in neuronal abnormalities. (A) Cartoon of Aldh1L1-DTA transgene; cre excises eGFP-Stop cassette allowing DTA transcription. (B) Regions targeted by Pax3-cre or Olig2-cre. (C and D) Pax3-cre:Aldh1L1-DTA mice show absence of GFP, neuropil, and congested appearance of NeuN (red) neurons in dorsal cord. (E) Cartoon of MN soma and synapse subtypes. CST, corticospinal tract. (F and G) We observed no differences in the number of cholinergic CHAT or vGlut2 (fig. S5) synapses. (H and I) Numbers of excitatory vGluT1-PSD95 synapses were significantly decreased, whereas (J and K) inhibitory vGAT-gephyrin synapses were significantly increased in bigenic animals compared with controls. For quantification, see fig. S5.

We tested whether astrocyte depletion could be used to assess local neuronal support functions using Olig2-cre:Aldh1L1-DTA mice, which were suitable because motor neurons (MNs, derived from pMN) are invested with several synaptic terminal types (Fig. 3E). Although we found a ~30% depletion of AldoC+ astrocytes in the ventral horns at P28 (fig. S4C), the number and size of MNs were unaffected (fig. S5, A and B). We counted choline acetyltransferase (CHAT)+ synaptic relays over the entire surface of MN soma but found no significant differences between DTA and control mice (fig. S5C). Similarly, we found no change in the number of vGluT2-PSD95+ (postsynaptic density 95) excitatory presynaptic inputs (fig. S5F). In contrast, there was a significant (P = 0.006) decrease in vGluT1-PSD95+ excitatory inputs from pro-prioceptive axons and a significant increase (P = 0.004) in vGAT-gephyrin+ inhibitory inputs in DTA mice (Fig. 3, H to K, and fig. S5, D and E). Thus, pMN-derived astrocytes are required for genesis and/or maintenance of certain types of synapses on MNs, and this function cannot be rescued by astrocytes from adjacent domains.

Is localized investment of astrocytes a general phenomenon throughout the CNS? We analyzed intercrosses of Emx1-cre, Dbx1-cre, or Nkx2.1-cre drivers, which label dorsal, intermediate, and ventral forebrain precursor cells, respectively, with a conditional Rosa-tdTomato reporter line or Aldh1L1-GFP. Forebrain astrocytes all demonstrated DV restriction associated with their domains of origin without detectable secondary migration (Fig. 4, A to N, and fig. S7A), even after injury (fig. S6). We observed many GFP+ cortical interneurons in Nkx2.1-cre:Rosa-tdTomato mice that migrate from the medial ganglionic eminence during development (Fig. 4, K to N). In sharp contrast, astrocytes derived from Nkx2.1-cre territory remained ventral (Fig. 4, J, L, and N).

Fig. 4.

Region-restricted astrocyte investment from forebrain radial glia. (A to D) Emx1-creERT2 (induced E17):Rosa26-tdTomato labeled cells; note (A′) distribution of astrocytes (green) confined to cortical plate and corpus callosum. Red box indicates region of cortex analyzed in (B) to (D). (E to I) Distribution of Dbx1-cre astrocytes in striatum. Red boxes indicate regions of cortex and striatum analyzed in (F) to (I). (J to N) Distribution of Nkx2.1-creERT2 (induced E17) astrocytes in ventromedial forebrain. Red box in cortex indicates fate-mapped interneurons. (O to S) Distribution of astrocytes after radial glial Ad-cre infection of P1 Z/EG reporter mice in the forebrain regions indicated analyzed at P4 or P28. Astrocytes were recognized by morphology and AldoC immunolabeling. We injected dorsal (n = 20), ventral (n = 21), medial (n = 19), and cortical (n = 17) brain regions (red arrows). No tangential astrocyte migration was observed. PALv, ventral pallidum.

Our transgenic cre-loxP approach labeled broad progenitor domains. For higher resolution, we targeted foci of radial glia by adenovirus-cre infection of the cortical surface of P1 Z/EG reporter mice (28), and analyzed the forebrains by GFP immunolabeling at P4 and P28 (Fig. 4, O to S, and fig. S7B). At P4, GFP+, AldoC+ immature astrocytes were found in close association with infected radial glial fibers (Fig. 4O). At P28, we observed restricted labeling of ep-endymal and astrocyte-like cells in the VZ and sub-VZ along with a trail of astrocytes distributed along the former trajectory of the radial glial processes (Fig. 4, P to R). This experiment was performed repeatedly (n = 77) to label DV and rostral-caudal regions comprehensively. Three-dimensional reconstructions of findings are summarized in Fig. 4S and movies S2 to S5. In every case, we found that the distribution of labeled astrocytes corresponded closely to the trajectories of the processes of their radial glial ancestors, in keeping with other findings in cortex (29).

Although certain astrocyte functions might be common throughout the CNS (e.g., formation of the BBB), other functions subserve the local neuronal circuitry and might be domain-specific. In this study we tested (i) whether astrocytes generated in different domains become intermixed or remain spatially segregated, (ii) whether neurons are functionally dependent on astrocytes that are generated from the same progenitor domains, and (iii) whether such domain-specific roles can be rescued by astrocytes from adjacent regions. Our data indicate that astrocytes migrate from the VZ in a strictly radial fashion, reminiscent of the columnar distribution of cortical projection neurons (30), forming well-defined, stable spatial domains throughout the CNS. We found no evidence for secondary tangential migration of FAs or PAs during development, adulthood, or after injury. Although some astrocytes may be derived from the division of local nonradial glial precursors (31), our study shows that they do not disperse tangentially. The restricted distribution of fore-brain astrocytes after neonatal adenovirus infection results in exquisite maps that reflect the original trajectory of their radial glial precursors. It follows that astrocytes might serve as a scaffold and retain spatially encoded information established during neural tube patterning—e.g., for purposes of axon guidance.

Astrocytes in various spatial domains might become specialized for interactions with their own particular neuronal neighbors as result of common patterning mechanisms. We selectively removed a fraction of pMN-derived astrocytes by targeted expression of DTA and found that numbers of certain synapses on MNs were altered. Our findings show that astrocytes from neighboring progenitor domains were unable to invade and rescue the depleted area, indicating essential region-specific neuron-astrocyte interactions. The transgenic tools we have developed allow for genetic manipulation of specific astro-cyte subgroups, e.g., to mis-specify their positional fate while leaving early VZ patterning and neuronal subtype specification intact. Our findings demonstrate that region-restricted astrocyte allocation is a general CNS phenomenon and reveal intrinsic limitations of the astroglial response to injury. They further suggest that astrocytes might act as stable repositories of spatial information necessary for development and local regulation of brain function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Wong, S. Kaing, U. Dennehy, M. Grist, and S. Chang for technical help and E. Huillard, V. Heine, and C. Stiles for helpful comments. We thank A. Leiter (University of Massachusetts, Worcester) for Ngn3-cre mice. L.C.F. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Fellow of the Helen Hay Whitney Foundation. R.T.-M. was funded by the Portuguese Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia. This work was supported by grants from the NIH, UK Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust, and European Research Council. A.A.-B. holds the Heather and Melanie Muss Chair of Neurological Surgery. D.H.R. is a HHMI Investigator.

Footnotes

References and Notes

- 1.Kettenmann H, Ransom BR. Neuroglia. Oxford Univ. Press; Oxford: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang DD, Bordey A. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;86:342. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doyle JP, et al. Cell. 2008;135:749. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Houades V, Koulakoff A, Ezan P, Seif I, Giaume C. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5207. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5100-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nimmerjahn A, Mukamel EA, Schnitzer MJ. Neuron. 2009;62:400. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bachoo RM, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402140101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cahoy JD, et al. J Neurosci. 2008;28:264. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noctor SC, Martínez-Cerdeño V, Ivic L, Kriegstein AR. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:136. doi: 10.1038/nn1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmechel DE, Rakic P. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1979;156:115. doi: 10.1007/BF00300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voigt T. J Comp Neurol. 1989;289:74. doi: 10.1002/cne.902890106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowitch DH. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:409. doi: 10.1038/nrn1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muroyama Y, Fujiwara Y, Orkin SH, Rowitch DH. Nature. 2005;438:360. doi: 10.1038/nature04139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hochstim C, Deneen B, Lukaszewicz A, Zhou Q, Anderson DJ. Cell. 2008;133:510. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levison SW, Goldman JE. Neuron. 1993;10:201. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90311-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Windrem MS, et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:553. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu X, Hill RA, Nishiyama A. Neuron Glia Biol. 2008;4:19. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X09000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okada S, et al. Nat Med. 2006;12:829. doi: 10.1038/nm1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robel S, Bardehle S, Lepier A, Brakebusch C, Götz M. J Neurosci. 2011;31:12471. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2696-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Materials and methods are available as supplementary materials on Science Online.

- 20.Masahira N, et al. Dev Biol. 2006;293:358. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shannon C, Salter M, Fern R. J Anat. 2007;210:684. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00731.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oberheim NA, et al. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3276. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4707-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cai J, et al. Development. 2007;134:1887. doi: 10.1242/dev.02847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao MS, Noble M, Mayer-Pröschel M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai HH, Macklin WB, Miller RH. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3571-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Q, Anderson DJ. Cell. 2002;109:61. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00677-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kessaris N, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:173. doi: 10.1038/nn1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merkle FT, Mirzadeh Z, Alvarez-Buylla A. Science. 2007;317:381. doi: 10.1126/science.1144914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magavi S, Friedmann D, Banks G, Stolfi A, Lois C. J Neurosci. 2012;32:4762. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3560-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rakic P. Science. 1988;241:170. doi: 10.1126/science.3291116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ge WP, Miyawaki A, Gage FH, Jan YN, Jan LY. Nature. 2012;484:376. doi: 10.1038/nature10959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.