Abstract

Background and purpose

It remains unclear whether direct vessel wall imaging can identify carotid high-risk lesions in symptomatic subjects and whether carotid plaque characteristics are more effective indicators for cerebral infarct severity than stenosis. This study sought to determine the associations of carotid plaque characteristics by MR imaging with stenosis and acute cerebral infarct (ACI) sizes on diffusion weighted imaging (DWI).

Materials and methods

One hundred and fourteen symptomatic patients underwent carotid and brain MRI. ACI volume was determined from symptomatic internal carotid artery territory on DWI images. Ipsilateral carotid plaque morphological and compositional characteristics, and stenosis were also determined. The relationships between carotid plaque characteristics, stenosis and ACIs size were then evaluated.

Results

In carotid arteries with 30–49% stenosis, 86.7% and 26.7% were found to have lipid-rich necrotic core (LRNC) and intraplaque hemorrhage, respectively. Furthermore, 45.8% of carotid arteries with 0–29% stenosis developed LRNCs. Carotid morphological measurements, such as % wall volume, and the LRNC size were significantly associated with ipsilateral ACIs volume before and after adjustment for significant demographic factors (age and LDL) or stenosis in patients with carotid plaque (all p < 0.05).

Conclusions

A substantial number of high-risk plaques characterized by vessel wall imaging exist in carotid arteries with lower grade stenosis. In addition, carotid plaque characteristics, particularly the % wall volume and LRNC size, are independently associated with cerebral infarction as measured by DWI lesions. Our findings indicate that characterizing atherosclerotic plaque by MR vessel wall imaging might be useful for stratification of plaque risk and infarction severity.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Carotid arteries, Magnetic resonance imaging, Plaque, Stenosis, Stroke

1. Introduction

Stroke has become the leading cause of death in China [1]. Disruption of high-risk carotid atherosclerotic plaques with subsequent thromboembolism is believed to be one of the major causes for ischemic stroke. Therefore, early characterization of carotid plaque vulnerability has been a key goal for prevention of cerebrovascular events.

Carotid luminal stenosis characterized by angiographic strategies has been used for evaluating the risk of atherosclerotic plaques clinically. Presence of carotid high-risk lesions, however, may not lead to significant lumen reduction due to positive remodeling of the arterial wall [2], and a number of high-risk plaques have been found in arteries with lower grade stenosis in previous studies [3,4]. MR black-blood vessel wall imaging has been demonstrated to be capable of accurately characterizing plaque morphology and tissue compositions [5–7]. Evidence has increasingly shown that carotid atherosclerotic plaques with high-risk features, such as large lipid-rich necrotic core (LRNC) [8], intraplaque hemorrhage (IPH) [9], or fibrous cap rupture (FCR) [10], are significantly associated with ischemic stroke.

However, most of these previous studies are based on recruiting high risk patients with a certain degree of carotid stenosis or stroke diagnosis by symptoms. It remains unclear if carotid plaque imaging is applied to a general ischemic stroke population without prior knowledge of stenosis, whether (1) more high-risk lesions will be identified as compared to measuring stenosis alone and (2) whether lesion characteristics are directly related to cerebral infarct lesion size which may be potentially an imaging metric of infarction severity. The aim of this study was to investigate whether more carotid high-risk lesions were identified by vessel wall MRI than stenosis alone, and test the hypothesis that if a patient has a carotid plaque with high-risk features, as identified by MRI, then the patient is more likely to have had larger acute cerebral infarcts (ACIs) determined by diffusion weighted imaging (DWI), appropriate to the side of the index carotid lesion.

2. Methods

2.1. Study populations

Patients with acute ischemic stroke in the anterior circulation presented in the emergency department were recruited for this study. All subjects underwent carotid artery and brain MR imaging within 1 week after onset of symptoms. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) high-risk cardioembolic sources; (2) other etiologies such as vasculitis, moyamoya disease or cancer-related stroke; (3) patients who had severe consciousness disturbance (coma) and contraindications to MR imaging. The institutional review board approved the study protocol prior to initiation and written informed consent was obtained from all the subjects.

2.2. MR imaging protocol

All recruited subjects were imaged on a whole body 3.0T MR scanner (Philips Achieva, Best, the Netherlands). A routine MR protocol, including T1-, T2-weighted and DWI, was used for brain imaging with an eight-channel head coil. The imaging parameters of DWI sequence are as follows: TR/TE 1598/46 ms, matrix of 128 × 128, slice thickness of 6 mm, and FOV of 24 cm × 24 cm.

For carotid MR imaging, a multi-contrast imaging protocol was performed with an eight-channel phased-array carotid coil to acquire the cross-sectional carotid MR images with the following parameters: (1) three-dimensional (3D) time of flight (TOF): TR/TE 20/5.1 ms, flip angle 20°; (2) quadruple inversion-recovery T1W sequence, two-dimensional (2D) TSE, TR/TE 800/10 ms; (3) T2W sequence with multi-slice double inversion recovery, TR/TE 4000/50 ms; and (4) 3D magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient-echo (MP-RAGE) sequence, IR TFE, TR/TE 9.2/5.5 ms, flip angle 15°. All carotid MR axial images were acquired with a FOV of 14 cm × 14 cm, slice thickness of 2 mm, acquisition matrix of 256 × 256, and longitudinal coverage of 32 mm (16 slices). The MR imaging was centered on the bifurcation of the symptomatic carotid arteries, which are defined as the arteries responsible for the neurological symptoms.

2.3. MR image review

Brain DWI images were evaluated by two experienced radiologists (>5 years of experience in neuroradiology) with consensus, blinded to clinical information and carotid MR images. Acute cerebral infarcts (ACIs) were defined as regions that were hyperintense on DWI images and hypointense on the apparent diffusion coefficient map. The presence or absence and the volume of ACIs were determined on the image of maximum contrast between lesion and normal brain regions (i.e., DWI with the highest b value) using a Philips MR workstation (Extended MR Workspace 2.6.3.1, Philips Medical System, Best, The Netherlands). DWI lesion volumes were assessed on the affected slices with hyperintense areas visible from the b = 1000 mm/s2 images. The readers paid particular attention to the typical locations of bilateral artifact and produced apparent diffusion coefficient maps as necessary to identify positive DWI lesions. The sum of the volumes for ACIs in the internal carotid artery (ICA) blood supplying territories were recorded for the hemisphere on the symptomatic side of each subject.

Carotid MR images in the symptomatic side were interpreted by two trained reviewers (X.Z., F.L.) with more than 3 years experience in carotid plaque imaging with consensus agreement using custom-designed software (CASCADE [11], Seattle, WA, USA), blinded to the brain MR images and clinical information. Image quality was rated per axial location on a four-point scale (1, poor; 2, marginal; 3, good; 4, excellent) dependent on the overall signal-to-noise ratio and clarity of the vessel wall boundaries. Slices with image quality <2 were excluded from review. The morphological measurements including the mean values of lumen area, wall area, total vessel area, and wall thickness (WT) were measured for each artery. The maximum WT and the % wall volume (100% × wall volume/total vessel volume) were also determined. Presence or absence of carotid plaque components, such as LRNC, calcification, IPH, and FCR, were identified according to previously published criteria validated by histology [5,6]. The volumes of each plaque component were also calculated. Carotid atherosclerotic plaque was defined as lesions with presence of any plaque component on MR images, such as calcification, LRNC, or IPH. The luminal stenosis of symptomatic carotid arteries was measured using NASCET criteria (percent stenosis = 100% × [1 − luminal diameter at the point of maximal narrowing/the diameter of the normal distal internal carotid artery]) on a Philips MR workstation. Carotid luminal stenosis was categorized into three categories including 0–29%, 30–49%, and ≥50%.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Continuous and binary variables were compared among the carotid arteries without plaque, with plaque and <50% stenosis, and with plaque and ≥50% stenosis using One Way ANOVA and Chi-square test, respectively. Associations between stenosis and other morphological features were assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Carotid plaque characteristics in different luminal stenosis categories were determined.

Associations between ACIs, patient demographics and carotid plaque measurements were assessed using regression based on generalized linear models. ACI volumes were analyzed as the dependent variable using gamma regression with a log link and associations reported as percent change in volume (%Δ). Multivariate regression analysis was used to assess independent associations between ACIs and carotid variables after adjustment for carotid luminal stenosis or patient demographics. To avoid including too many variables in one model, a smaller set of demographics were selected for multivariate adjustment by first entering all demographics with p < 0.20 during univariate analysis and then applying backwards elimination until only those with p < 0.05 remained. All statistical analysis was performed using R 2.11.0 (R Development Core Team (2010). R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A p value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

Between September 2009 and July 2010, 116 subjects meeting the inclusion criteria were recruited for this study. Two subjects were excluded due to overall poor carotid artery image quality. Of the remaining 114 subjects, 81 were male (71.1%), and the mean age was 63.6 ± 10.4 years. Demographic and imaging characteristics were compared between subjects without plaque, with plaque and <50% stenosis, and with plaque and ≥50% stenosis (Table 1). No significant differences in demographic variables were found during comparison. An increasing trend was observed in the volumes of ICA territory ACIs in carotid arteries without plaque, with plaque and <50% stenosis, and with plaque and ≥50% stenosis (p < 0.001, Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and imaging characteristics of the study population (N [%] or mean ± SD).

| All subjects (n = 114) | Comparison of carotid arteries

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without plaque (n = 38) | With plaque and <50% stenosis (n = 59) | With plaque and ≥50% stenosis (n = 17) | p value | ||

| Gender, male | 81 (71.1) | 23 (60.5) | 44 (74.6) | 15 (88.2) | 0.237 |

| Age (years old) | 63.6 ± 10.4 | 61.5 ± 10.2 | 63.7 ± 10.8 | 68.5 ± 8.6 | 0.072 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.3 ± 2.8 | 24.3 ± 3.4 | 24.2 ± 2.5 | 24.8 ± 2.1 | 0.684 |

| History of hypertension | 93 (81.6) | 32 (84.2) | 45 (76.3) | 16 (94.1) | 0.106 |

| History of diabetes mellitus | 44 (38.6) | 12 (31.5) | 25 (42.4) | 8 (47.1) | 0.733 |

| History of smoking | 63 (55.3) | 16 (42.1) | 34 (57.6) | 13 (76.5) | 0.056 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.9 ± 1.0 | 4.9 ± 1.0 | 4.9 ± 1.0 | 5.1 ± 1.3 | 0.657 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 0.513 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.574 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 1.9 ± 1.3 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 0.304 |

| ICA territory ACIs (mL) | 5.1 ± 7.9 | 2.8 ± 4.0 | 4.1 ± 6.7 | 13.9 ± 12.1 | <0.001 |

| NIHSS | 4.5 ± 3.5 | 4.6 ± 3.3 | 4.2 ± 3.7 | 5.6 ± 3.0 | 0.331 |

The p value was determined by comparing carotid arteries without plaque, with plaque and <50% stenosis, and with plaque and ≥50% stenosis. BMI, body mass index; LDL, low density lipoprotein; HDL, high density lipoprotein; ICA, internal carotid artery; NIHSS, NIH stroke score.

3.1. Carotid plaque features in different luminal stenosis categories

Carotid plaque morphological and compositional features in different stenosis categories are summarized in Table 2. Positive correlations between carotid luminal stenosis and maximum wall thickness (r = 0.76, p < 0.001) and % wall volume (r = 0.81, p < 0.001) were found. The plaque burden and the prevalence of carotid plaque compositional features were found to increase as luminal stenosis increases. Of note, in carotid arteries with 30–49% stenosis, 86.7%, 26.7%, and 6.7% were found to have LRNC, IPH, and FCR, respectively. Furthermore, 45.1% of carotid arteries with 0–29% stenosis were found to have LRNC.

Table 2.

The distribution of carotid plaque features across different luminal stenosis categories (mean ± SD or N [%]).

| Carotid plaque features | Carotid stenosis category

|

p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–29% (n = 82) | 30–49% (n = 15) | ≥50% (n = 17) | ||

| Lumen area (mm2) | 49.2 ± 13.9 | 36.5 ± 11.5 | 31.6 ± 15.5 | <0.001 |

| Wall area (mm2) | 25.6 ± 5.4 | 33.0 ± 9.5 | 42.1 ± 14.0 | <0.001 |

| Total vessel area (mm2) | 74.7 ± 17.2 | 69.4 ± 15.3 | 73.7 ± 20.9 | 0.561 |

| Mean WT (mm) | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | <0.001 |

| Max WT (mm) | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 3.8 ± 1.3 | 6.0 ± 1.9 | <0.001 |

| % wall volume (%) | 34.8 ± 5.3 | 47.8 ± 9.3 | 57.8 ± 11.5 | <0.001 |

| Presence of calcification | 23 (28) | 12 (80.0) | 15 (88.2) | <0.001 |

| Presence of LRNC | 37 (45.1) | 13 (86.7) | 17 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| Presence of IPH | 0 (0.0) | 4 (26.7) | 10 (58.8) | <0.001 |

| Presence of FCR | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.7) | 4 (23.5) | <0.001 |

3.2. Association between carotid atherosclerosis and volume of ACIs in ICA territory

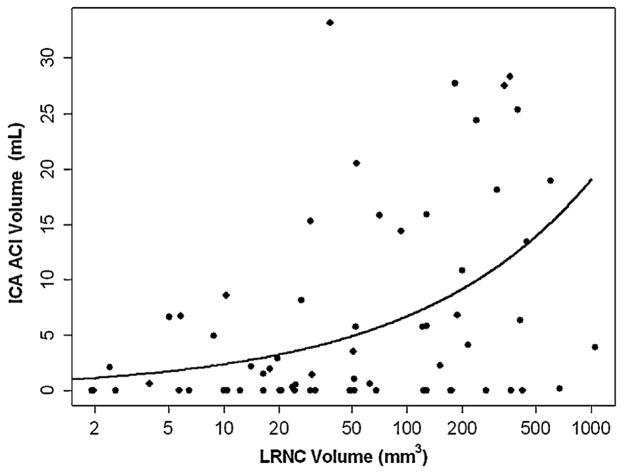

Associations between carotid atherosclerosis and volume of ACIs in ICA territory are summarized in Table 3. For carotid arteries with plaque, significant associations of volume of ACIs in ICA territory with carotid luminal stenosis, maximum WT, % wall volume, and LRNC volume (Fig. 1) were found during univariate analysis. After adjusting for significant demographic factors including age and LDL, the associations remained statistically significant. In contrast, significant associations between volume of ACIs in ICA territory and LRNC volume were observed after adjusting for carotid luminal stenosis. There was a marginal association between volume of ACIs in ICA territory and % wall volume after adjusting for luminal stenosis (p = 0.05). Figs. 2 and 3 are examples showing subjects with carotid large LRNC and ipsilateral ACIs.

Table 3.

Summary of univariate and multivariate analysis between carotid variables and volume of ACIs in the subjects with carotid plaque by vessel wall imaging (n = 76).

| Carotid plaque features | Volume of ICA territory ACIs

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate

|

Multivariate (model 1)

|

Multivariate (model 2)

|

||||

| %Δ (95% CI) | p value | %Δ (95% CI) | p value | %Δ (95% CI) | p value | |

| Luminal stenosisa | 4.3 (1.6, 7.2) | 0.003 | – | – | 2.8 (0.3, 5.3) | 0.029 |

| Max WT (mm)a | 11.1 (3.4, 19.2) | 0.005 | 5.6 (−4.1, 16.3) | 0.273 | 7.5 (0.8, 14.6) | 0.030 |

| % wall volumea | 33.5 (14.1, 56.2) | 0.001 | 24.9 (0.4, 55.4) | 0.050 | 22.9 (8, 39.9) | 0.003 |

| Calcification volume (mm3)a,b | −0.7 (−3.0, 1.6) | 0.554 | −1.0 (−3.3, 1.4) | 0.411 | 0.7 (−1.6, 3.0) | 0.544 |

| LRNC volume (mm3)a,b | 4.4 (2.2, 6.7) | <0.001 | 3.2 (0.3, 6.2) | 0.037 | 2.5 (0.3, 4.7) | 0.026 |

| IPH volume (mm3)a,b,c | 0.2 (−6.5, 7.4) | 0.952 | – | – | – | – |

%Δ = percent increase in volume per increase in demographic variable.

Per 10% increase.

Only including those with the corresponding component present.

Too few patients for multivariate analysis.

Model 1 = adjusted for carotid stenosis. Model 2 = adjusted for significant demographic factors, age and LDL cholesterol.

Fig. 1.

The associations between ACI volumes and carotid LRNC volumes. Scatter plot of ACI volume in the ICA territory versus LRNC volume in those with LRNC present. The solid line is the fitted mean value from a generalized linear model. LRNC volume is shown on the log scale due to its strong right skewness.

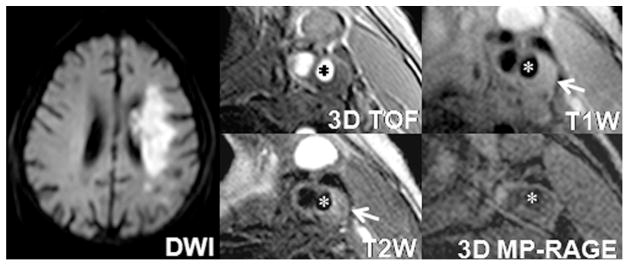

Fig. 2.

An example of a subject with lipid-rich atherosclerotic plaque and ipsilateral ACIs. An atherosclerotic plaque with large LRNC (iso-intensity on T1-weighted image and hypointensity on corresponding T2-weighted image, arrow) is detected in the left internal carotid artery (star). Cerebral DWI demonstrates ACIs (hyperintensity) at left hemisphere.

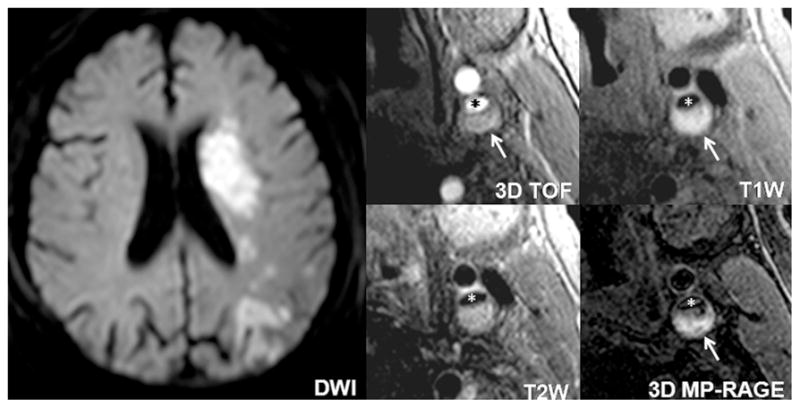

Fig. 3.

An example of a subject with atherosclerotic plaque with large LRNC and ipsilateral ACIs. A high-risk plaque with large LRNC occupied by IPH (hyperintensity on TOF, T1-weighted and MP-RAGE images, arrow) is observed in the left internal carotid artery (star). Cerebral DWI demonstrates large ACIs (hyperintensity) at the ICA territory of left hemisphere.

4. Discussion

This is a cross-sectional study to investigate whether more carotid high-risk lesions can be identified by vessel wall imaging than stenosis as well as the associations of carotid plaque characteristics with cerebral infarcts in patients with ischemic cerebrovascular events. We found that a substantial number of carotid arteries with lower grade stenosis developed high-risk plaque features, such as IPH and FCR. In addition, we found that both carotid plaque morphological and compositional characteristics were significantly associated with the size of ipsilateral ACIs before and after adjustment for significant demographic factors or carotid luminal stenosis. These findings suggest that direct vessel wall imaging may be important in subjects with stroke to better determine its etiology and to select optimal treatment options. Indeed, a recent study by Freilinger et al. argues that a portion of cryptogentic stroke may actually be carotid atherosclerosis related once plaque imaging is used in the evaluation [12].

Levels of luminal stenosis have been considered as a useful cut off point for carotid high-risk plaque characterization clinically [13]. However, in this study, we found a substantial number of LRNCs and IPHs in carotid arteries with lower grade stenosis (<50% lumen reduction) although there was a strong correlation between plaque burden measurements and luminal stenosis. Our findings are in line with previous studies. In a study by Saam et al., 21.7% of carotid arteries with 16–49% stenosis were observed to develop complicated plaques: defined as the presence of IPH, FCR, or calcium nodule [3]. A study by Dong et al. documented presence of IPH in 8.7% of patients with 0% stenosis in carotid arteries [14]. Recently, investigators have shown that in carotid arteries with <50% stenosis, 98.2% and 28.6% have LRNC and IPH, respectively [4]. This phenomenon might be explained by the hypothesis of positive remodeling [2]. Our findings of high-risk plaque features existing in arteries with lower grade stenosis offer further compelling evidence that luminal stenosis is limited as a discriminator of carotid high-risk plaque.

In this study, carotid plaque characteristics, particularly the % wall volume and LRNC size, were found to be associated with the size of ipsilateral ACIs, which has been used for assessment of severity and prognosis of ischemic stroke outcomes [15]. Ouhlous et al. studied 41 patients with symptomatic carotid severe stenosis and found that carotid plaques with LRNC are related to the extent of cerebral infarcts determined by fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images [16]. These findings suggest that patients with carotid high risk plaque features may be at high risk of developing cerebral infarction. Our finding indicates that patients with large LRNC carotid plaques may suffer from larger cerebral infarction than those with tiny LRNC plaques, although the associations in the present study are likely nonlinear. This study suggests that in carotid plaques with similar volume and compositional features, the size of LRNC, may be used to further differentiate the risk for cerebral infarction or its severity.

We found the association of carotid plaque characteristics with the size of cerebral infarcts to be independent of luminal stenosis. In the present study, carotid luminal stenosis can be observed to be associated with volume of ACIs in ICA territory. This may be due to the hypothesis of decreases in blood perfusion resulting from lumen reduction. However, after adjustment for luminal stenosis, the association between volume of ACIs in ICA territory and carotid plaque characteristics remained significant, indicating there may be another etiology of ischemic stroke beyond luminal stenosis. Previous studies have demonstrated that ischemic stroke can be seen in patients with carotid mild to moderate luminal stenosis [17]. It is well established that disruption of vulnerable plaques triggers the formation of thromboembolic and subsequent ischemic events regardless of the extent of luminal stenosis. As such, characterization of carotid plaque features by vessel wall imaging rather than measuring luminal stenosis alone is suggested for stratification of the ischemic stroke severity.

Because this is a cross-sectional study, it cannot evaluate the correlation of progression of carotid atherosclerotic disease with future cerebrovascular events. A prospective study with large patient pool is warranted to assess the relationship between carotid plaque features and the severity of future ischemia or infarction. Another limitation of this study is that we evaluated the disease severity using calculation of volume of DWI lesions regardless of the blood flow and lesion location, particularly the important functional regions that are highly associated with neurological symptoms [18]. In addition, we only imaged less than 40 mm of longitudinal coverage centered on the carotid bifurcation using black-blood TSE imaging sequences which is takes longer scan time (>30 min) and limits the detection of atherosclerotic lesions occurring in more distal or more proximal segments. Recently, faster black blood imaging techniques such as double-inversion recovery turbo field echo (TFE) [19] and 3D MERGE [20] were proposed for carotid plaque imaging. These techniques allow carotid artery vessel wall imaging with large longitudinal coverage and short scan time.

5. Conclusion

Compared to measuring luminal stenosis alone, more high-risk plaques can be identified by direct MR vessel wall imaging. In addition, carotid atherosclerotic plaque morphological and compositional characteristics, particularly the % wall volume and the size of LRNC, are significantly associated with severity of cerebral infarction as measured by DWI lesions, even after adjustment for traditional risk factors or carotid luminal stenosis. Our findings indicate that non-invasively characterizing carotid atherosclerotic plaque by MR vessel wall imaging maybe useful to better select proper treatment options of stroke subjects.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources

This work was supported by a Grant from Shanghai Leading Academic Discipline Project (S30203), a Grant from Philips Healthcare, Grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81271536 and 81271575), and Grants from NIH (HL 56874 and HL 103609).

We would like to thank Zach Miller for his assistance in preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Liu L, Wang D, Wong KS, et al. Stroke and stroke care in China: huge burden, significant workload, and a national priority. Stroke. 2011;42:3651–4. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.635755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glagov S, Weisenberg E, Zarins CK, et al. Compensatory enlargement of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries. New England Journal of Medicine. 1987;316:1371–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198705283162204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saam T, Underhill HR, Chu B, et al. Prevalence of american heart association type VI carotid atherosclerotic lesions identified by magnetic resonance imaging for different levels of stenosis as measured by duplex ultrasound. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;51:1014–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao X, Underhill HR, Zhao Q, et al. Discriminating carotid atherosclerotic lesion severity by luminal stenosis and plaque burden: a comparison utilizing high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging at 3. 0 tesla. Stroke. 2011;42:347–53. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.597328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai JM, Hatsukami TS, Ferguson MS, et al. Classification of human carotid atherosclerotic lesions with in vivo multicontrast magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2002;106:1368–73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000028591.44554.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saam T, Ferguson MS, Yarnykh VL, et al. Quantitative evaluation of carotid plaque composition by in vivo MRI. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2005;25:234–9. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000149867.61851.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinton DP, Cury RC, Chan RC, et al. Bright and black blood imaging of the carotid bifurcation at 3. 0 T. European Journal of Radiology. 2006;57:403–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demarco JK, Ota H, Underhill HR, et al. MR carotid plaque imaging and contrast-enhanced mr angiography identifies lesions associated with recent ipsilateral thromboembolic symptoms: an in vivo study at 3 T. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2010;31:1395–402. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altaf N, Daniels L, Morgan PS, et al. Detection of intraplaque hemorrhage by magnetic resonance imaging in symptomatic patients with mild to moderate carotid stenosis predicts recurrent neurological events. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2008;47:337–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan C, Zhang SX, Polissar NL, et al. Identification of fibrous cap rupture with magnetic resonance imaging is highly associated with recent transient ischemic attack or stroke. Circulation. 2002;105:181–5. doi: 10.1161/hc0202.102121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerwin W, Xu D, Liu F, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of carotid atherosclerosis: plaque analysis. Topics in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2007;18:371–8. doi: 10.1097/rmr.0b013e3181598d9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freilinger TM, Schindler A, Schmidt C, et al. Prevalence of nonstenosing, complicated atherosclerotic plaques in cryptogenic stroke. JACC Cardiovascular Imaging. 2012;5:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayberg MR, Wilson SE, Yatsu F, et al. Carotid endarterectomy and prevention of cerebral ischemia in symptomatic carotid stenosis, Veterans affairs cooperative studies program 309 trialist group. Journal of American Medical Association. 1991;266:3289–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong L, Underhill HR, Yu W, et al. Geometric and compositional appearance of atheroma in an angiographically normal carotid artery in patients with atherosclerosis. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2010;31:311–6. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baird AE, Dambrosia J, Janket S, et al. A three-item scale for the early prediction of stroke recovery. Lancet. 2001;357:2095–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)05183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ouhlous M, Flach HZ, de Weert TT, et al. Carotid plaque composition and cerebral infarction: MR imaging study. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2005;26:1044–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi M, Ogasawara K, Inoue T, et al. Endarterectomy for mild cervical carotid artery stenosis in patients with ischemic stroke events refractory to medical treatment. Neurologia Medico-Chirurgica (Tokyo) 2008;48:211–5. doi: 10.2176/nmc.48.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoo AJ, Barak ER, Copen WA, et al. Combining acute diffusion-weighted imaging and mean transmit time lesion volumes with national institutes of health stroke scale score improves the prediction of acute stroke outcome. Stroke. 2010;41:1728–35. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.582874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen J, Di YJ, Bu CQ, et al. A comparative analysis of double inversion recovery tfe and tse sequences on carotid artery wall imaging. European Journal of Radiology. 2012;81:223–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balu N, Yarnykh VL, Chu B, et al. Carotid plaque assessment using fast 3D isotropic resolution black-blood MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2011;65:627–37. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]