Abstract

The endophytic fungus strain 0248, isolated from garlic, was identified as Trichoderma brevicompactum based on morphological characteristics and the nucleotide sequences of ITS1-5.8S- ITS2 and tef1. The bioactive compound T2 was isolated from the culture extracts of this fungus by bioactivity-guided fractionation and identified as 4β-acetoxy-12,13- epoxy-Δ9-trichothecene (trichodermin) by spectral analysis and mass spectrometry. Trichodermin has a marked inhibitory activity on Rhizoctonia solani, with an EC50 of 0.25 μgmL−1. Strong inhibition by trichodermin was also found for Botrytis cinerea, with an EC50 of 2.02 μgmL−1. However, a relatively poor inhibitory effect was observed for trichodermin against Colletotrichum lindemuthianum (EC50 = 25.60 μgmL−1). Compared with the positive control Carbendazim, trichodermin showed a strong antifungal activity on the above phytopathogens. There is little known about endophytes from garlic. This paper studied in detail the identification of endophytic T. brevicompactum from garlic and the characterization of its active metabolite trichodermin.

Keywords: Trichoderma brevicompactum, garlic, endophytic fungus, Trichodermin, antifungal activity

Introduction

An increased concern over the widespread use of toxic agricultural chemicals and an increased recognition of the potential of biological pesticides has stimulated much research to develop and implement the use of biological pesticides (Epstein and Bassein, 2003; Strobel and Daisy, 2003). Chemical pesticides have been the objects of substantial criticism in recent years, mainly due to their adverse effects on the environment, human health and other non-target organisms (Raju et al., 2003). The potential use of microbe-based biocontrol agents as replacements or supplements for agrochemicals has been addressed in many recent reports (Hynes and Boyetchko, 2006; Vasudevan et al., 2002). Endophytes are microorganisms that live in the intercellular spaces of stems, petioles, roots and leaves of plants, and there is no discernible manifestation of their presence (Strobel and Long, 1998; Yang et al., 2011). The symbiosis between plants and endophytes is well known; specifically, the former protects and feeds the latter, which ‘in return’ produces bioactive (plant growth regulatory, antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, insecticidal, etc.) substances to enhance the growth and competitiveness of the host in nature (Carroll 1988; Konig et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1994). Accordingly, endophytes are currently considered to be a wellspring of bioactive secondary metabolites with the potential for medical, agricultural, and/or industrial exploitation (Schulz et al., 2002; Tan et al., 2000).

Garlic (Allium sativum), a member of the family Liliaceae, contains an abundance of chemical compounds that have antimicrobial, anticancer and antioxidant activity (Omar and Al-Wabel, 2010). However, little is known about the secondary metabolites of endophytes harbored inside the healthy garlic tissues. To find fungi for potentially efficient biopesticides, we isolated the endophytic isolates from plants such as garlic and carried out a bioassay against phytopathogens. The candidate isolate 0248 showed strong inhibitory activity against phytopathogens. In this paper, the identification of the endophytic fungus isolate 0248 from garlic by morphological and molecular characteristics is described. The purification and characterization of antifungal metabolites from the fermentation broth of isolate 0248 are also studied.

Materials and Methods

Endophytic fungus and phytopathogenic strains

The endophytic fungus 0248 was isolated from healthy garlic based on antifungal activity. The phytopathogenic fungal strains, including Fusarium oxysporum, Colletotrichum lindemuthianum, C. ampelinum, Rhizoctonia solani and Botrytis cinerea, were kindly provided by the Institute of Plant Protection and Microorganisms, Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences. These strains were separately stored on PDA slants containing potato-dextrose agar at 4 °C until used.

Culture conditions for isolate 0248

Fresh mycelium were picked and inoculated into 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 mL PD medium. After 2 days of incubation at 28 ± 1 °C on a rotary shaker at 150 rpm, 3 mL culture liquid was transferred as seeds into a 300-mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 30 mL medium (20 gL−1 dextrose, 5 gL−1 peptone, 1 gL−1 beef extract, 0.001 gL−1 ZnSO47H2O and 0.01 gL−1 NH4Cl). The resulting culture was kept on a rotary shaker at 180 rpm for 4 days at 28 ± 1 °C. The fermentation broth was separated from the mycelia by filtration through filter paper using a Buchner funnel. One hundred milligrams mycelial biomass was taken following washing (two times) with sterile Tris-EDTA buffer for DNA extraction.

Identification of the endophytic fungus isolate 0248

The candidate isolate 0248 was identified by using morphological and molecular procedures. The morphological examination was performed by observing the characteristics of fungal culture on PDA, yeast extract sucrose agar (YES)(40 gL−1 yeast extract, 160 gL−1 sucrose and 20 gL−1 agar) and synthetic low-nutrient agar (SNA) (1.0 gL−1 KH2PO4, 1.0 gL−1 KNO3, 0.5 gL−1 MgSO47H2O, 0.5 gL−1 KCl, 0.2 gL−1 dextrose, 0.2 gL−1 Sucrose and 20 gL−1 agar) in Petri dishes, separately. Microscopic slides were prepared and examined under a light microscope (Leica, German). Total genomic DNA was extracted from fresh mycelium according to the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB, Sigma) procedure (Cappiccino and Sherman, 1996).

A region of nuclear rDNA, containing the internal transcribed spacer regions 1 and 2 and the 5.8S rDNA gene region, was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the primer pair ITS1 (5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTA TTGATATGC-3′) with the following protocol: 1 min initial denaturation at 94 °C, followed by 30 cycles of 1 min denaturation at 94 °C, 1 min primer annealing at 50 °C and 90 s extension at 74 °C, and a final extension period of 7 min at 74 °C. A fragment of tef1 was amplified by the primer pair tef1 fw (5′-GTGAGCGTGGTATCACCATCG-3′) and tef1 rev (5′-GCCATCCTTGGAGACCAGC-3′) with the following amplification protocol: 1 min initial denaturation at 94 °C, followed by 30 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 59 °C and 50 s at 74 °C, and a final extension period of 7 min at 74 °C (Kraus et al., 2004). PCR products were sequenced by Shanghai Invitrogen Co. (Shanghai, China). The DNA sequence obtained was submitted to GenBank and TrichoKEY for homology analysis by BLASTN and TrichoKEY 2 program, respectively. Phylogenetic trees were inferred using the neighbor-joining (NJ) algorithm (Saitou and Nei, 1987) from the PHYLIP suite programs (Felsenstein 1995). The topologies of the resulting unrooted trees were evaluated in a bootstrap analysis (Felsenstein 1985) based on 500 resamplings of the NJ dataset using the PHYLIP package.

Analytical conditions

Silica gel (200–300 mesh) for column chromatography and GF254 (30–40 μm) for TLC were produced by Qingdao Marine Chemical Factory, Qingdao, China. All other chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade. IR spectra were recorded in KBr disks on an FTIR-8400S instrument. All NMR experiments were performed on a Bruker AM 500 FTNMR spectrometer using TMS as the internal standard. Mass spectrometry (MS) data were obtained using an Agilent-5873 mass spectrometer at 70 eV.

Antifungal assay

Antifungal activity was tested with the hyphae growth velocity assay (Lu et al., 2000). The effective concentration of the sample causing a 50% inhibition of mycelial growth (EC50) was determined. The commercial antifungal agent carbendazim, produced by NingXia Sanxi Chemical Co., Ltd. China, was used as positive control. Mycelial discs (4 mm in diameter) of phytopathogenic fungi grown on PDA were cut from the margins of the colony and placed on the same medium containing different concentrations of the sample. A negative control was maintained with sterile water mixed with PDA medium. Each treatment had three replicates. The diameter of colony growth was measured when the fungal growth in the control had completely covered the Petri dishes. The inhibition percentage of mycelial growth was calculated as follows:

where Da represents control colony diameter and Db represents treated colony diameter. The colony diameter is in millimeters.

Gas chromatographic analysis

The active compound was dissolved in HPLC grade methanol and quantified by GC (Agilent 6890N) with an HP-5 capillary column (5% phenyl methyl siloxane, 30 m × 320 μm × 0.25 μm) with an FID detector and nitrogen as the carrier gas. The injector temperature was 250 °C, the detector temperature was 270 °C, the column temperature rose by program with an initial temperature of 100 °C maintained for 5 min and rising to 260 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1 and maintained for 5 min. The flow rate of N2 was 1.5 mL min−1.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis were performed using SPSS 15.0 software. The log dose-response curves allowed determination of the EC50 for the fungi bioassay according to probit analysis. The 95% confidence limits for the range of EC50 values were determined by the least-square regression analysis of the relative growth rate (% control) against the logarithm of thecompound concentration(Rabea et al., 2009).

Results

Identification of the endophytic fungus isolate 0248

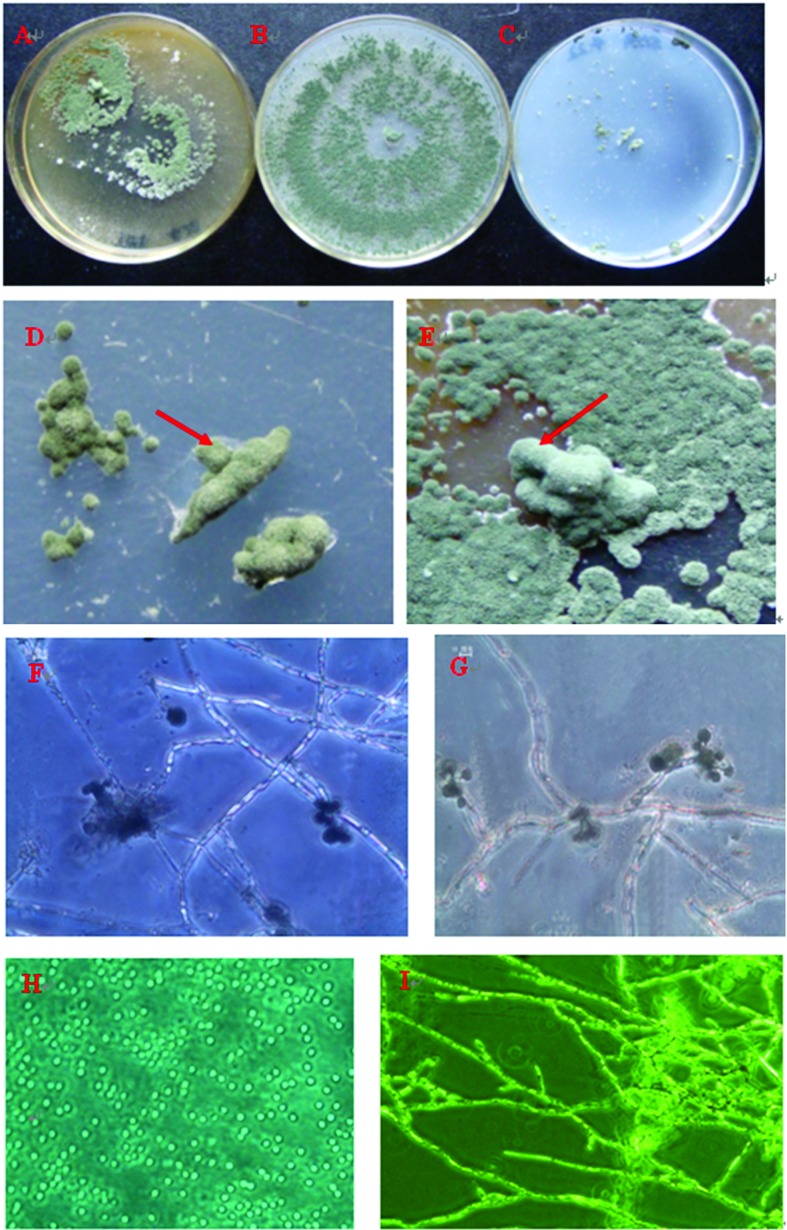

On PDA medium, the isolate 0248 mycelium grew rapidly at 28 ± 1 °C in darkness. The aerial mycelia were white to green and colorless on the reverse side of the plate. After 6 days at 28 ± 1 °C conspicuous concentric rings were present, and colonies with a regular margin were 90 mm in diameter. No diffuse pigment or odor was noted. However, cultures of isolate 0248 grown on YES and SNA tended to form pustules and grew slowly. Colonies did not grow radially on SNA. This result might be due to component difference of PDA, SNA and and YES. All colonies sporulated on PDA, SNA and YES medium at 28 ± 1 °C in the dark. On PDA, conidiomata grew from stromata and consisted of single conidiophores that were grey-green, smooth, and oval to spherical. The diameter of conidiophores was 5.5–7.0 μm (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Morphology of isolate 0248. A, Appearance of colonies on YES; B, Appearance of colonies on PDA; C, Appearance of colonies on SNA; D, Appearance of pustules on SNA (arrow); E, Appearance of pustules on YES (arrow); F–I, hypha and conidia.

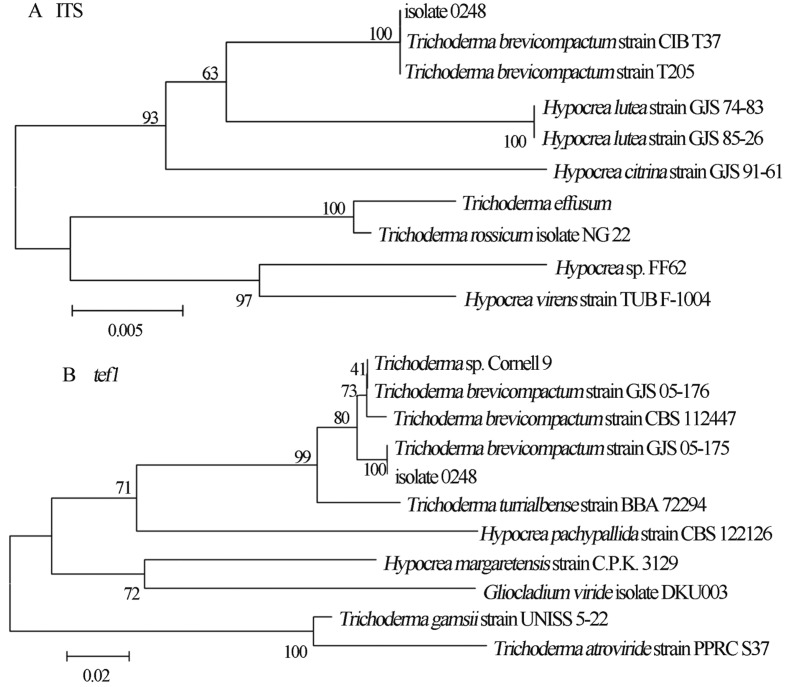

The sequences of the region of ITS1-5.8S- ITS2 (GenBank accession number JN257218) and the fragment of tef1 (GenBank accession number JN257219) were obtained in this study. The comparison of ITS1-5.8S- ITS2 and tef1 genes of isolate 0248 with sequences in the GenBank database revealed that this endophytic fungus was highly homologous to different strains of Trichoderma brevicompactum, with nucleotide identities 99–100% for ITS1-5.8S- ITS2 and 97–100% for tef1. The topology of the phylogram in Figure 2 confirmed that 100% bootstrap values were detected between the ITS1-5.8S- ITS2 and tef1 sequences of isolate 0248 and those of T. brevicompactum. Therefore, isolate 0248 was closely related to T. brevicompactum.

Figure 2.

A Neighbor-joining tree based on ITS rDNA sequence of isolate 0248 and its closest ITS rDNA matches in GenBank. Values on the nodes indicate bootstrap percent confidence. B Neighbor-joining tree based on tef1 sequence of isolate 0248 and its closest tef1 matches in GenBank. Values on the nodes indicate bootstrap percent confidence.

TrichoKEY2 is a program for the quick molecular identification of Hypocrea and Trichoderma on the genus and species levels based on an oligonucleotide DNA BarCode (www.isth.info), a diagnostic combination of several oligonucleotides (hallmarks) specifically allocated within the internal transcribed spacer 1 and 2 (ITS1 and 2) sequences of the rRNA gene cluster (Druzhinina et al., 2005). Identification of isolate 0248 using the oligonucleotide barcode showed that it belongs to the species T. brevicompactum and that the identification reliability was high.

Extraction and purification of metabolites of the endophytic fungus

The isolation of active compounds from strain 0248 was carried out with a bioassay against R. solani, and the fractions with antifungal activity were used for further isolation. The fermentation broth (total volume 30 L) of isolate 0248 was collected and extracted three times with ethyl acetate (filtrate/ethyl acetate 1:1, v/v) at ambient temperature. A brown residue (8.25 g) was obtained by evaporating the solvent from the extract in a vacuum; the residue was separated by chromatography over a silica gel column (200 g, 100–200 mesh), eluting successively with 1000 mL each of petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (v/v, 30:1, 20:1, 10:1, 8:1, 6:1, 4:1, 2:1, and 1:1) and acetone to obtain 8 fractions (A1~A8). A5 was re-chromatographed over a silica gel column (50 g, 100–200 mesh) eluted with 500 mL each of petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (v/v, 20:1, 15:1, 10:1, 5:1, and 1:1), ethyl acetate and acetone, obtaining 4 fractions (4B1~4B4). Based on the TLC monitoring and antifungal test, 4B2 was further separated over a silica gel column (25 g, 100–200 mesh) eluted with 100 mL each of petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (v/v, 10:1, 9:1, 8:1, 7:1, 6:1, 5:1, 4:1, 3:1, 2:1 and 1:1) and acetone to give fractions 5C1~5C15. 5C9 and 5C10 were combined to yield 258 mg active compound T2.

Structure elucidation of antifungal compound T2

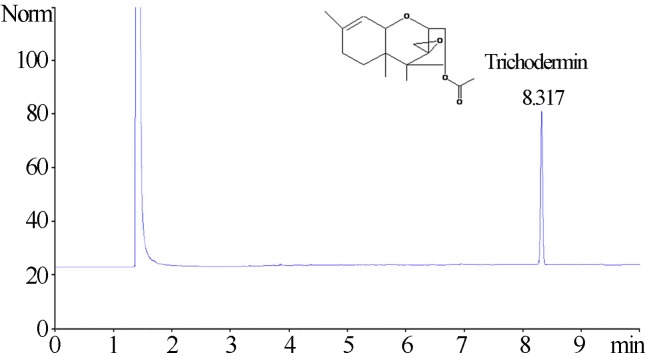

Compound T2, which had strong antifungal activity, was identified as 4β-acetoxy-12, 13-epoxy-Δ9-trichothecene (trichodermin) by spectral analysis, MS data and direct comparison with published information (Godtfredsen and Vangedal, 1965). Colorless crystal (pentane), mp 45–46 °C; + 10.2° (c 0. 1 mg mL−1, CHCl3); IR: [α]D20 (cm−1) 2900, 1732, 1374, 1243 and 1080 cm−1; The molecular formula of compound T2 was determined to be C17H24O4 by its spectral data (1H, 13C NMR and DEPT), MW 292.16746, 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ: 5.506(dd, 1H, J = 6.4, 3.2 Hz, H-4), 5.337–5.350(m, 1H, H-10), 3.757(d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1 H, H-2), 3.546(d, 1H, J = 4.4 Hz, H-11), 3.059(d, 1 H, J = 3.2 Hz, H-13), 2.768 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H, H-13′), 2.473(dd, J = 12.4, 6.4 Hz, 1H, H-3), 2.021(s, 3H, H-18), 1.951~1.865(m, 4 H, H-8, H-8′, H-7, H-3′), 1.653 (s, 3H, H-16), 1.354(m, 1H, H-7′), 0.875(s, 3H, H-15), 0.658 (s, 3H, H-14). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ: 170.71(C-17), 139.94(C-9), 118.42(C-10), 78.89(C-2), 74.86(C-4), 70.28(C-11), 65.30(C-12), 48.70(C-5), 47.62(C-13), 40.19(C-6), 36.44(C-3), 27.77(C-8), 24.24 (C-7), 23.06(C-16), 20.93(C-18), 15.78(C-15), 5.60(C-14). The spectrum of trichodermin used for quantitative analysis by GC is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Representative gas chromatography of trichodermin isolated and purified from fermentation broth by isolate 0248.

Antifungal activities

The results of the antifungal activity of trichodermin against R. solani, F. oxysporum, C. lindemuthianum, C. ampelinum and B. cinerea were expressed as EC50 and are presented in Table 1. We observed that trichodermin markedly inhibits R. solani, with an EC50 of 0.25 μgmL−1. Trichodermin also strongly inhibits B. cinerea, with an EC50 of 2.02 μgmL−1. However, trichodermin had a poor inhibitory effect against C. lindemuthianum (EC50 = 25.60 μgmL−1). The results also indicated that the inhibitory effect of trichodermin differed with regard to the type of the fungi. Compared with the positive controls, trichodermin has broad-spectrum and strong antifungal activity.

Table 1.

Antifungal activities of trichodermin on mycelial growth of pathogenic fungi.

| Microorganisms | EC50 (μgmL−1) | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Trichodermin | Carbendazim | |

| Rhizoctonia solani | 0.25 | 0.36 |

| Fusarium oxysporum | 8.51 | 10.35 |

| Colletotrichum lindemuthianum | 25.60 | > 50.00 |

| Colletotrichum ampelinum | 16.65 | > 50.00 |

| Botrytis cinerea | 2.02 | > 50.00 |

Discussion

In our efforts to screen for suitable microorganisms from garlic that can produce bioactive compounds, we found that isolate 0248, subsequently identified as T. brevicompactum, showed strong antifungal activities. This is the first study of the endophytic fungus from garlic. T. brevicompactum, a new species, was first confirmed by morphological, molecular, and phylogenetic analyses in 2004, and related research has been very rare. Trichoderma species are common soil-borne fungi. One of the most significant ecological niches occupied by Trichoderma species is the plant rhizosphere (Harman et al., 2004). The concept of Trichoderma as an endophyte has received a less attention.

Although Trichoderma isolates were isolated from live sapwood below the bark of trunks of wild and cultivated Theobroma cacao and other Theobroma species (Evans et al., 2003), only a small number of Trichoderma isolates from the collection have been studied for their biocontrol activities (Bailey et al., 2008; Holmes et al., 2004; Samuels et al., 2006a, 2006b). However, it is unclear which compounds produced by these isolates have inhibitory activity against phytopathogens (Howell 2003). Purification of secondary metabolites from fermentation broths can be a challenging task due to the complexity of the medium, the inherent instability of the molecular structures or by the action of enzymes present in the fermentation broth, leading to poor isolation yield and loss of antibiotic activity. In this paper, we studied the isolation and purification of an active metabolite from the endophytic T. brevicompactum fermentation broth in detail and identified trichodermin as the main active compound.

It is well known that trichodermin is a very potent inhibitor of protein synthesis (Carrasco et al., 1973). Reports of trichodermin activity against phytopathogens are less common. We studied the inhibitory activity of trichodermin against mycelial growth of plant pathogenic fungi and showed that it has potential value in agricultural applications. It was found that endophytic T. brevicompactum from garlic produced approximately 86 mgL−1 trichodermin in liquid cultures. This is a marked increase in trichodermin production compared with previous reports, in which T. harzianum Th008 produced approximately 92.67 μgL−1 trichodermin in liquid cultures of PDB (Bertagnolli et al., 1998). Therefore, the high production of trichodermin and its high antifungal activity highlight the potential of this endophytic T. brevicompactum isolate in antibiotic production. In addition, very little was previously known about the nature of the relationship between T. brevicompactum and the garlic plant. Whether trichodermin has any influence on garlic growth is also an interesting possibility and should be researched in future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Fundation of China (30940018), Zhejiang Province Programs for Science and Technology Development (2010C32063C32011R09027-03, and 2013C32008) and Zhejiang Province Natural Science Fundation (LY12C14012)

References

- Bailey BA, Bae H, Strem MD, Crozier J, Thomas SE, Samuels GJ, Vinyard BT, Holmes KA. Antibiosis, mycoparasitism, and colonization success for endophytic Trichoderma isolates with biological control potential in Theobroma cacao. Biol Control. 2008;46:24–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bertagnolli BL, Daly S, Sinclair JB. Antimycotic compounds from the plant pathogen Rhizoctonia solani and its antagonist Trichoderma harzianum. J Phytopathol. 1998;146:131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Cappiccino JG, Sherman N. Microbiology a laboratory manual. 6th ed. The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company; Redwood City, CA, USA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco L, Barbacid M, Vazquez D. The trichodermin group of antibiotics, inhibitors of peptide bond formation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Nucleic Acids and Protein Synthesi. 1973;312:368–376. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(73)90381-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll GC. Fungal endophytes in stems and leaves: from latent pathogen to mutualistic symbiont. J Ecology. 1988;69:2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Druzhinina I, Kopchinskiy AG, Komon M, Bissett J, Szakacs G, Kubicek CP. An oligonucleotide barcode for species identification in Trichoderma and Hypocrea. Fungal Genet and Biol. 2005;42:813–828. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein L, Bassein S. Patterns of pesticide use in California and the implications for strategies for reduction of pesticides. Ann Rev Phytopathol. 2003;41:351–355. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.41.052002.095612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans HC, Holmes KA, Thomas SE. Endophytes and mycoparasites associated with an indigenous forest tree, Theobroma gileri, in Ecuador and a preliminary assessment of their potential as biocontrol agents of cocoa diseases. Mycol Prog. 2003;2:149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. PHYLIP (Phylogenetic Inference Package), Version 3.75. Departament of Genetics, University of Washington; Seattle: 1995. Distributed by author. [Google Scholar]

- Godtfredsen WO, Vangedal S. Trichodermin, a new sesquiterpene antibiotic. Acta Chem Scand. 1965;19:1088–1102. doi: 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.19-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman G, Howell CR, Viterbo A, Chet I, Lorito M. Trichoderma species. opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat Rev. 2004;2:43–56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes KA, Schroers HJ, Thomas SE, Evans HC, Samuels GJ. Taxonomy and biocontrol potential of a new species of Trichoderma from the Amazon basin in South America. Mycol Prog. 2004;3:199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Howell CR. Mechanisms employed by Trichoderma species in the biological control of plant diseases: the history and evolution of current concepts. Plant Dis. 2003;87:4–10. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2003.87.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RK, Boyetchko SM. Research initiatives in the art and science of biopesticide formulations. Soil Biol Biochem. 2006;38:845–849. [Google Scholar]

- Konig GM, Wright AD, Aust HJ, Draeger S, Schulz B. Geniculol, a new biologically active diterpene from the endophytic fungus Geniculosporium sp. J Nat Prod. 1999;62:155–157. doi: 10.1021/np9802670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus GF, Druzhinina I, Gams W, Bissett J, Zafari D, Szakacs G, Koptchinski A, Prillinger H, Zare R, Kubicek CP. Trichoderma brevicompactum sp. nov Mycologia. 2004;96:1059–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Zou WX, Meng JC, Hu J, Tan RX. New bioactive metabolites produced by Colletotrichum sp., an endophytic fungus in Artemisia annua. Plant Sci. 2000;15:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Omar SH, Al-Wabel NA. Organosulfur compounds and possible mechanism of garlic in cancer. Saudi Pharm J. 2010;18:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabea EI, Badawy-Mohamed EI, Steurbaut W, Stevens CV. In vitro assessment of N-(benzyl)chitosan derivatives against some plant pathogenic bacteria and fungi. Eur Polym J. 2009;45:237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Raju NS, Niranjana SR, Shetty H. Effect of Pesudomonas fluorescens and Trichoderma harzianum on head moulds and seed qualities of sorghum. Crop Improv. 2003;30:6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbour-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels GJ, Dodd S, Lu BS, Petrini O, Schroers HJ, Druzhinina I. The Trichoderma koningii aggregate species. Studies in Mycol. 2006;56:67–133. doi: 10.3114/sim.2006.56.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels GJ, Suarez C, Solis K, Holmes KA, Thomas SE, Ismaiel A, Evans HC. Trichoderma theobromicola and T. paucisporum: two new species from South America. Mycol Res. 2006;110:381–392. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz B, Boyle C, Draeger S, Römmert AK, Krohn K. Endophytic fungi: a source of novel biologically active secondary metabolites. Mycol Res. 2002;106:996–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Strobel G, Daisy B. Bioprospecting for microbial endophytes and their natural products. Microbiol Mol Biol R. 2003;67:491–502. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.491-502.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel GA, Long DM. Endophytic microbes embody pharmaceutical potential. ASM News. 1998;64:263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Tan RX, Meng JC, Hostettmann K. Phytochemical investigation of some traditional Chinese medicines and endophyte cultures. Pharm Biol. 2000;38:22–32. doi: 10.1076/phbi.38.6.25.5955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan P, Kavitha S, Priyadarsini VB, Babuje L, Gnanamanickam SS. Biological control of rice diseases. In: Gnanamanickam SS, editor. Biological Control of Crop Diseases. New York, Basel: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 2002. pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yang SX, Gao JM, Zhang Q, Laatsch H. Toxic polyketides produced by Fusarium sp., an endophytic fungus isolated from Melia azedarach. Bioorg & Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:1887–1889. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Strobel G, Stierle A, Hess WM, Lee J, Clardy J. A fungal endophyte-tree relationship: Phoma sp. in Taxus wallachiana. Plant Sci. 1994;102:1–9. [Google Scholar]