Abstract

A case of extensive chromoblastomycosis of the right leg and thigh with verruciform to nodular lesions evolving rapidly over five years duration is reported. The diagnosis was confirmed by visualizing pathognomonic pigmented muriform bodies with unique septate hyphae and mycological culture yielding Fonsecaea pedrosoi.

Keywords: chromoblastomycosis, extensive, India

Chromoblastomycosis is a chronic subcutaneous mycotic infection caused by several pigmented fungi common being Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Cladophialophora carrionii and Phialophora verrucosa. Fonsecaea pedrosoi is the commonest causative agent implicated. These fungi are saprophytic in the environment in soil detritus, vegetation, wood splinters, and thorns and implanted by trauma into the skin of exposed body parts (Lopez Martinez and Mendez Tovar 2007). The infection is frequently seen in agriculturists, labourers, carpenters and those walking bare foot. Usually the males in tropical and sub-tropical rural areas are affected. A small, single, localized papule, nodule, plaque or verrucoid lesion is seen, primarily on lower extremity Severe clinical forms and extensive involvement of cutaneous, sub-cutaneous regions due to lymphatic, hematogenous or autoinoculation are rare occurrences and difficult to treat (Ameen 2009, Muhammed et al., 2006).

A healthy looking male adult, 51 years of age, farmer by occupation, presented with a five years history of cutaneous lesions with exacerbation and rapid progression over the last two years. To begin with, a pea sized raised lesion developed over lower medial aspect of right leg. It gradually increased in size to involve the medial side and front of the whole leg and extended over the thigh (Figure 1 A and B). Lesions were severely itchy and raw areas were painful. The patient complained of pus discharge from the lesions. There was no antecedent trauma or self manipulation. He remained afebrile during this period and no other systemic complaints were reported. A similar disease was not reported in the family. Past and personal history was non-contributory. When the patient attended the Dermatology Department, examination revealed a geographical lesion on the medial aspect and front of leg and thigh about 40 cm × 15 cm. The lesion was crusted, verrucous with violaceous borders and a sero-sanginous discharge was exuding. General physical examination was remarkable for tender, enlarged inguinal lymph glands on right side. Vitals were within normal limits. Haematological and biochemical parameters were normal. Patient was immunocompetent and non-diabetic. Clinical possibilities of chromoblastomycosis, verrucous carcinoma or tuberculosis veruca cutis (TBVC) were entertained. Skin scrapings sent for 10% KOH showed pigmented sclerotic bodies along with septate hyphae (Figure 2) confirming the diagnosis. Biopsy sample cultured on Sabouraud’s Dextrose Agar (SDA) with antibiotics grew a melanized fungus after 10–15 days of incubation at 25 °C. Microscopy was suggestive of Fonsecaea pedrosoi and isolate was sent for revised opinion to the National Culture Collection of Pathogenic Fungi, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh where culture was confirmed as Fonsecaea pedrosoi. Treatment was initiated with saturated solution of potassium iodide (SSKI) in a dose of 10 drops thrice daily. A combination of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid 625 mg TDS was instituted to treat secondary bacterial infection. Symptomatic management of itching was done with anti-allergic agents. The dose of SSKI was increased to 15 drops on the third day. Oral itraconazole 400 mg/day in two divided doses was added after 5 days along with potassium permanganate soaks. Recurrence of secondary bacterial infection was treated with cotrimoxazole with subsequent addition of metronidazole. After two weeks, there was no significant regression of lesions and oral terbenfine in a dosage of 250 mg, 12 hourly started. Cryotherapy was also instituted along with itraconazole and terbenafine and favourable response was seen with some regression of lesions after a month. Extent of lesions demanded a prolonged compliance which was not achievable unfortunately as patient has not reviewed in the last three months.

Figure 1.

(A): Severe chromoblastomycosis of right lower limb extending from lower leg to thigh. (B): Nodular elevated, violaceous and verruciform dry lesions interspersed with healing ulcers on upper leg and thigh.

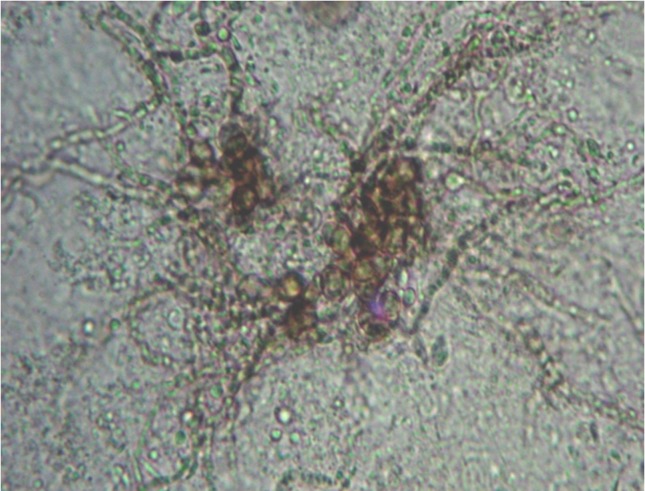

Figure 2.

Sclerotic cells with radiating pigmented septate fungal hyphae on a potassium hydroxide preparation.

Chromoblastomycosis is a non-fatal, chronic, invariably localized infection with solitary lesions of the skin and sub-cutaneous tissue (Lopez Martinez and Mendez Tovar 2007, Merg and Hay 2005). The clinical picture in the present case eluded diagnosis due to the rare occurrence of extensive lesions which progressed rapidly over 5 years time. Such widespread disease is known to evolve over an average of 20 years and may be misdiagnosed for premalignant or malignant conditions (Queiroz-Telles et al., 2003, Rasul et al., 2007). Flavio has described five types of lesions in chromoblastomycosis which includes nodular, tumorous, verruciform, cicatricial and plaque types. The type of lesions in the present case were a combination of nodular type with moderately elevated violaceous growths interspersed with typical verruciform type showing hyperkeratotic dry lesions at places. The lesions were categorised in severe form involving extensive adjacent cutaneous regions (Queiroz-Telles, McGinnis, Salkin and Graybill 2003). As per the scoring system for staging chromoblastomycosis given by Castro et. al. (Castro 1992) our case was classified as having severe disease with 8 points. The area of lesion was larger than 25 cm2 but less than 100 cm2 - 2 points, metastatic lesion - 3 points, complicated by ulceration and secondary infection - 2 point and resistant to treatment - 1 point.

The fungus usually confines itself to the sub-cutaneous tissue. Draining lymph nodes may participate in pathological process. Complications like ulceration and lymphedema may appear when the whole limb is affected (Ameen 2009, Bharti et al., 1995, Lopez Martinez and Mendez Tovar 2007). There are chances of secondary bacterial infections worsening the primary disease symptoms resulting in itching, peculiar odour and unrest. It is also implicated in genesis of lymph stasis and consequent elephantiasis. Scratching may lead to autoinoculation with secondary lesions (Ameen 2009, Bharti, Malhotra, Bal and Sharma 1995). Lymphatic dissemination sometimes showing progressive lesions arising in a sporotrichoid fashion are documented (Muhammed, Nandakumar, Asokan and Vimi 2006, Nair and Sarojini 1993). Hematogenous spread has been reported to account for involvement of large areas (Azulay and Serruya 1967). The patient presented to us with extensive involvement and it is difficult to comment the spread though involvement of regional lymph nodes corroborates lymphatic spread rather than autoinoculation or hematogenous extension.

A variety of melanised fungi are implicated in causation of chromoblastmycosis with Fonsecaea pedrosoi being the most common (El Euch et al., 2010, Menezes et al., 2008, Silva et al., 1998). Irrespective of the causative fungus, characteristic brown, thick-walled, globe-shaped, multi-septate, muriform sclerotic bodies, 4–12 μm in diameter represent the single most important diagnostic feature. Various workers have reported demonstration of sclerotic bodies in 80–90% cases and our results of direct microscopy concur these findings (Correia et al., 2010, Sharma et al., 1999). In our case, we could visualize characteristic sclerotic cells and brown pigmented, septate, hyphal elements as well which are not reported previously and is a unique feature.

The agent F. pedrosoi is notorious to treatment and no single antifungal agent or regimen has demonstrated satisfactory results consistently (Ameen 2009). Therapies are tried in various combinations and permutations and similar management protocols have shown variable results which are related to the causative agent, disease severity and the choice of antifungal. Cryotherapy is ideal, though comparatively expensive for mild disease. Antifungal agents like itraconazole or terbinafine alone or in combination with cryotherapy have been used for large lesions (Ameen 2009, Queiroz-Telles, McGinnis, Salkin and Graybill 2003). Successful use of amphotericin B with itraconazole in a case of extensive chromoblastomycosis is reported in medical literature (Paniz-Mondolfi et al., 2008). Modalities have to be matched with individual tolerance and affordability by the patient. For localized lesions, SSKI is a cheap and efficacious agent. Considering the low socio-economic status of the patient, therapy with SSKI was started but was in-effective in our case unlike experienced by other authors where two weeks treatment with SSKI showed dramatic results with subsequent cure (Nair and Sarojini 1993). A combination of SSKI with itraconazole 400 mg/day did not show any favourable response either. Inclusion of oral terbenafine 500 mg daily in two divided doses and cryotherapy achieved sub-optimal results but patient was lost to follow-up before adequate remission.

The present case reflects the need to suspect chromoblastomycosis in cases with widespread lesions. The poor economic status of patients and their inability to afford long and expensive antifungal treatment leads to non-compliance. This hampers all efforts of clinicians and laboratory physicians to diagnose and treat chromoblastomycosis satisfactorily.

References

- Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azulay RD, Serruya J. Hematogenous dissemination in chromoblastomycosis. Report of a generalized case. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti R, Malhotra SK, Bal MS, Sharma K. Chromoblastomycosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1995;61:54–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro LG. Chromomycosis: a therapeutic challenge. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:553–4. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.3.553-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia RT, Valente NY, Criado PR, Martins JE. Chromoblastomycosis: study of 27 cases and review of medical literature. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:448–54. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962010000400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Euch D, Mokni M, Haouet S, Trojjet S, Zitouna M, Ben Osman A. Erythematous type scaly papule on the abdomen: chromoblastomycosis due to Fonsecaea pedrosoi. Med Trop (Mars) 2010;70:81–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Martinez R, Mendez Tovar LJ. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:188–94. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menezes N, Varela P, Furtado A, Couceiro A, Calheiros I, Rosado L, Mota G, Baptista A. Chromoblastomycosis associated with Fonsecaea pedrosoi in a carpenter handling exotic woods. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merg WG, Hay RJ. Chromoblastomycosis. In: Esterre P, editor. Medical Mycology Topley and Wilson’s Microbiology and Microbial Infections. 10th ed. Hodder Arnold; London: 2005. pp. 356–66. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammed K, Nandakumar G, Asokan KK, Vimi P. Lymphangitic chromoblastomycosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:443–5. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.29342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair PS, Sarojini PA. Chromoblastomycosis resembling sporotrichosis. Ind J Dermatol Leprol Venereol. 1993;59:125–6. [Google Scholar]

- Paniz-Mondolfi AE, Colella MT, Negrin DC, Aranzazu N, Oliver M, Reyes-Jaimes O, Perez-Alvarez AM. Extensive chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea pedrosoi successfully treated with a combination of amphotericin B and itraconazole. Med Mycol. 2008;46:179–84. doi: 10.1080/13693780701721856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz-Telles F, McGinnis MR, Salkin I, Graybill JR. Subcutaneous mycoses. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:59–85. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(02)00066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasul ES, Hazarika NK, Sharma A, Borua PC, Sen SS. Chromoblastomycosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2007;55:149–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma NL, Sharma RC, Grover PS, Gupta ML, Sharma AK, Mahajan VK. Chromoblastomycosis in India. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:846–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva JP, de Souza W, Rozental S. Chromoblastomycosis: a retrospective study of 325 cases on Amazonic Region (Brazil) Mycopathologia. 1998;143:171–5. doi: 10.1023/a:1006957415346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]