Abstract

Chronic exposure to elevated levels of free fatty acids (FFAs) has been shown to cause cell death (lipotoxicity), but the underlying mechanisms of lipotoxicity in hepatocytes remain unclear. We have previously shown that the saturated FFAs cause much greater toxicity to human hepatoma cells (HepG2) than the unsaturated ones (Srivastava and Chan, 2007). In this study, metabolic flux analysis (MFA) was applied to identify the metabolic changes associated with the cytotoxicity of saturated FFA. Measurements of the fluxes revealed that the saturated FFA, palmitate, was oxidized to a greater extent than the non-toxic oleate and had comparatively less triglyceride synthesis and reduced cystine uptake. Although fatty acid oxidation had a high positive correlation to the cytotoxicity, inhibitor experiments indicated that the cytotoxicity was not due to the higher fatty acid oxidation. Application of MFA revealed that cells exposed to palmitate also had a consistently reduced flux of glutathione (GSH) synthesis but greater de novo ceramide synthesis. These predictions were experimentally confirmed. In silico sensitivity analyses identified that the GSH synthesis was limited by the uptake of cysteine. Western blot analyses revealed that the levels of the cystine transporter xCT, but not that of the GSH-synthesis enzyme glutamylcysteine synthase (GCS), were reduced in the palmitate cultures, suggesting the limitation of cysteine import as the cause of the reduced GSH synthesis. Finally, supplementing with N-acetyl L-cysteine (NAC), a cysteine-provider whose uptake does not depend on xCT levels, reduced the FFA-toxicity significantly. Thus, the metabolic alterations that contributed to the toxicity and suggested treatments to reduce the toxicity were identified, which were experimentally validated.

Keywords: metabolism, free fatty acid, toxicity, ceramide, glutathione, cystine transporter

Introduction

Hepatocytes play a central role in whole-body lipid metabolism and free fatty acids (FFAs) have been shown to play an important role in the development of such hepatic disorders as steatosis and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (Farrell and Larter, 2006). Steatosis refers to a condition where there is excess accumulation of lipids inside the cells, leading to altered cellular function. While benign by itself, steatosis primes the cells to injury by oxidative insults (Angulo and Lindor, 2002). It has been suggested that about 30% of the population in the US suffers from steatosis (Browning et al., 2004). Of those, 20% of the patients develop NASH (McCullough, 2006). One of the important markers of NASH is extensive hepatocyte cell death and increased serum aspartate transaminase (AST)/alanine transaminase (ALT) levels, an indicator of hepatocyte injury. FFAs have emerged as one of the primary factors in the development of NASH (Scheen and Luyckx, 2002). However, the mechanisms behind FFA toxicity remain unclear. It is important to elucidate the alterations in overall cellular metabolism in order to understand the development of this disease and devise effective treatments.

Previous studies have identified that the saturated FFAs are much more toxic to hepatocytes and hepatoma cells than the mono and poly-unsaturated FFAs (Malhi et al., 2006; Srivastava and Chan, 2007; Wei et al., 2006). It has also been shown that metabolism of these fatty acids is essential for their cytotoxic response (Shimabukuro et al., 1998). It is a reasonable hypothesis that the differences in the metabolism of the saturated and unsaturated FFAs contribute to their differences in cytotoxicity. Therefore, we studied the global changes in the metabolism of these cells in response to FFAs by applying metabolic flux analysis (MFA). MFA has previously been applied to understand the hypermetabolism of hepatocytes following burn injury (Lee et al., 2003), to optimize hepatocyte functions for bio-artificial liver applications by identifying the changes in hepatocyte metabolism on exposure of plasma (Chan et al., 2003a) and the effects of supplementing the media with hormones and amino acids (Chan et al., 2003b). MFA has also been applied to identify the metabolic effects of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1α), to identify if HIF-1α can be a potential target in cancer treatment (Kim and Forbes, 2006).

In the current study, MFA was applied to identify the changes in metabolism in response to the saturated and unsaturated FFAs for a period of 3 days. MFA, coupled with in silico sensitivity analyses, indicated that the GSH synthesis was limited primarily by the supply of cysteine. Supplementing the cells with N-acetyl L-cysteine (NAC), which provides cysteine independently of the xCT activity (Sato et al., 2005), increased the glutathione (GSH) synthesis and significantly reduced the toxicity of palmitate. Thus, the metabolic alterations induced by saturated FFAs were identified by MFA and served as targets to regulate the FFA toxicity, which were experimentally confirmed.

Materials and Methods

Materials

HepG2/C3A cells and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with high glucose and no pyruvate, Penicillin–Streptomycin (P/S) and phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Fatty acid free bovine serum albumin (BSA) was purchased from MP Biomedicals (Chillicothe, OH). Sodium salts of palmitate, oleate, and linoleate were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO). Enzymatic kits for measurement of glucose, lactate, and free glycerol were purchased from Sigma, while those for triglyceride and beta-hydroxybutyrate measurement were purchased from Stanbio Laboratories (Boerne, TX). Free Fatty Acid Half Micro kit was purchased from Roche Biochemicals (Indianapolis, IN). AccQTag amino acid analysis HPLC column, AccQTag solvent and the sample preparation reagents were purchased from Waters Corp. (Milford, MA).

Cell Culture and Cytotoxicity Measurements

HepG2 cells were chosen in this study because they have been shown to retain many hepato-specific functions and have been suggested as good models of hepatic metabolism (Guo et al., 2006; Javitt, 1990; Sakai et al., 2001). Many studies have employed HepG2 cells to study lipid metabolism, including the effects of exposure to fatty acids (Dashti et al., 2000; Furth et al., 1992; Guo et al., 2006; Kosone et al., 2007; Strauss et al., 2003). The cells were cultured in 6-well plates in 2 mL DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Confluent cells were treated with the medium containing either the vehicle (4% BSA) or 0.7 mM palmitate or oleate complexed to 4% BSA. The cytotoxicity was measured (using cytotoxicity detection kit from Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) as the fraction of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released into the medium, normalized to the total LDH (released + lyzed), as shown in the equation below:

| (1) |

Flux Measurements

The fluxes of various metabolites were measured according to (Chan et al., 2003a, b). The linearity of some fluxes over this interval was verified (see Figure SF1, for example). The concentrations of glucose, lactate, FFA, glycerol, and glycerol were measured by enzymatic kits from Sigma–Aldrich, while beta-hydroxybutyrate and triglycerides were measured using enzymatic kits from Stanbio Laboratories. These metabolites were assayed according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The concentration of acetoacetate in the media was measured by an enzymatic fluorimetric assay (Olsen 1971). Concentrations of Asp, Glu, Gly, NH3, Arg, Thr, Ala, Pro, Tyr, Val, Met, Orn, Lys, Ile, Leu, and Phe were measured by the AccQTag amino acid analysis method (Waters) coupled with fluorescence detection. The concentrations of Ser, Asn, Gln, and His were measured by a modification of the AccQTag method. Cystine concentration in the media and supernatants was measured using HPLC according to a previously published protocol (Fiskerstrand et al., 1993). All the measured fluxes were normalized to total protein in the cell extract, measured with the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method (Pierce Chemicals, Rockford, IL).

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA)

Assumptions

The assumptions employed in the current study with respect to the MFA model are stated below:

Pseudo-steady state was assumed. MFA requires that the intracellular metabolites be under the condition of pseudo-steady state, that is there is no significant accumulation of any metabolite. Experiments were conducted to verify this assumption (see section in Supplementary file).

The fluxes of metabolites are linear over the 24 h period. Fluxes of the uptake or release of metabolites were assumed to be linear over the 24 h period, such that the net change in the extracellular concentration of the metabolite after 24 h duration represents the flux of that metabolite. See Figure 1b in Supplementary file for verification of this assumption.

The secretion of triglycerides is much less than its accumulation. A previous study has shown that HepG2 cells have active synthesis but impaired secretion of lipids (Gibbons et al., 1994). We measured the secretion of triglycerides in response to various treatments and observed that the levels of extracellular TG were much less than that of the intracellular TG (not shown). Even though there was significant accumulation of TG inside the cells, this does not invalidate the pseudo steady state assumption because TG, if not exported, is sequestered into separate compartments as lipid droplets. Thus, the intracellular TG could be considered as an “external/extra-cytosolic” flux (Chan et al., 2003a,b).

The metabolites are uniformly distributed inside the cell. This assumption implied that a single MFA model could be applied to perform metabolite balances and separate models were not needed for the various compartments (organelles). Many previous studies have found that this is a fair assumption for mammalian cells (Banta et al., 2004; Chan et al., 2003a, b).

There is no formation of cysteine from methionine. HepG2 cells cannot synthesize cysteine from methionine due to the lack of S-adenosyl-methionine synthetase activity (Lu and Huang, 1994). Therefore, this equation was not included in the model.

Either fatty acid synthesis or its oxidation dominates: formation of a stable system of equation requires that none of the equations be linear combinations of any other equation(s). Meeting this requirement meant that only one of the bidirectional pathways be considered. Therefore, it was assumed that, in the FFA-treated cells, the exogenous FFA supply was much greater than the de novo fatty acid synthesis, and the latter may be neglected. Opposite assumption was made for the BSA control cells, that is, fatty acid oxidation was neglected. These assumptions were chosen based on observations (significantly greater ketone body release in cells treated with fatty acids) as well as the literature (reduced de novo lipogenesis in the presence of FFAs) (Lelliott et al., 2005; Muto and Gibson, 1970).

Cysteine degradation is negligible: a recent study has found that the HepG2/C3A cells do not contain the enzymes of the primary pathway of cysteine degradation (such as cysteine dioxygenase (CDO) and cysteine sulfinic acid decarboxylase (CSAD) (Dominy et al., 2007). An alternative route of cystine degradation is through cysteine lyase (CL)/cystathionase to yield ammonia, pyruvate and hydrogen sulfide. However, an in vitro study found that the cleavage of cysteine was at least two orders of magnitude slower than that of cystathionine and no detectable cleavage of cystine by cysteine lyase from HepG2 cells (Steegborn et al., 1999). Therefore, the authors of that study questioned the in vivo significance of CL in cysteine degradation. Therefore, we did not include the equations for cysteine degradation in the MFA model. Nonetheless, we did test the effects of including the cysteine degradation (through CDO and/or CL) on the fluxes of the system, including GSH synthesis. The flux through the cysteine degradation pathway was always negligible. None of the other fluxes, including GSH synthesis, were significantly affected when cysteine degradation was included in the MFA.

Based on these assumptions, MFA models consisting 85 or 86 cellular metabolic reactions (for control and FFA-treated cells, respectively) involved in the metabolism of glucose, protein, and lipids (including the synthesis of sphingo- and phospho-lipids) was developed (see table ST2 in Supplementary section for details of the reactions). The model consisted of 66 intracellular metabolites for control and palmitate-treated cells and 67 for oleate-treated cells (Table ST3 in Supplementary section). In order to solve the system of equations, 29 metabolic fluxes were measured (Table ST4). This yielded an over-determined system of equations which was solved by least-squares fit using the Moore–Penrose pseudo-inverse calculation.

Correlation Analysis

Correlation analysis was conducted to identify the relationships between the metabolic fluxes and toxicity. It must be emphasized, however, that the correlation coefficients do not suggest a causal relationship between the metabolic fluxes and toxicity. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between the different metabolic fluxes (calculated by the MFA) and the measured toxicity (LDH release) for the 3 days. The fluxes with very high correlation (both positive and negative) to the toxicity were evaluated by altering those fluxes using inhibitors or additional supplementation of the metabolite and measuring their effect on toxicity.

Sensitivity Analyses

To determine the effect of an extracellular flux on the intracellular flux of interest, sensitivity studies were conducted in silico. The values of a desired extracellular flux were varied while keeping all other fluxes constant and the resulting intracellular fluxes were calculated by MFA. Flux of a desired metabolite was varied within ±10% of the measured value (Daae and Ison, 1999; Essington, 2003; Krohn et al., 1997) and the effect on the flux of interest was calculated. For example, the effect of changing the uptake of palmitate was evaluated on the synthesis of ceramide. Within this perturbation range, there was no significant effect on the other fluxes, except those directly associated with the metabolite that was perturbed.

Western Blotting

The expression of the heavy subunit of glutamyl-cysteine synthase (GCS-H) and xCT (a subunit of system Xc- which transports cystine into the cell) were measured using Western blotting. After desired treatments, the cells were washed twice with PBS and scraped off in 200 μL CellLytic M buffer (Sigma). The cells were sonicated in this buffer and centrifuged at 10,000g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatants were mixed with sample loading buffer (5X from Cell Signaling Technologies) containing the reducing agent and heated at 95°C for 10 min, followed by cooling on ice for 2 min and short centrifugation to collect the condensate. Equal amounts of protein were loaded on a 10% Tris-HCl gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and electrophoresed at 110 V for 95 min. Samples were then blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane at 110 V for 60 min, followed by blocking of the membrane in 5% fat-free milk solution in Tris buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) for 1 h at RT. Samples were then incubated overnight in the presence of primary antibody for GCS-H or xCT (both from Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA, and used at a dilution of 1:1,000) in TBS-T. After the incubations, the membranes were washed three times with TBS-T, followed by exposure to secondary antibody (1:2,000 dilution in TBS-T of goat anti-rat IgG from Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) for 1 h at RT. Blots were then washed thrice for 5 min each with TBS-T and developed using Supersignal West Femto substrate (Pierce Biotechnology) and imaged using a Bio-Rad imager. Following the imaging, the blots were washed thrice with TBS-T and exposed to anti-beta-actin antibody (1:2,000 in TBS-T) overnight, then washed thrice and exposed to anti-mouse IgG for 1 h in TBS-T (1:5,000 dilution). Blots were washed again and imaged by measuring the chemiluminiscence for 1 min.

Results

Cytotoxicity of the FFAs

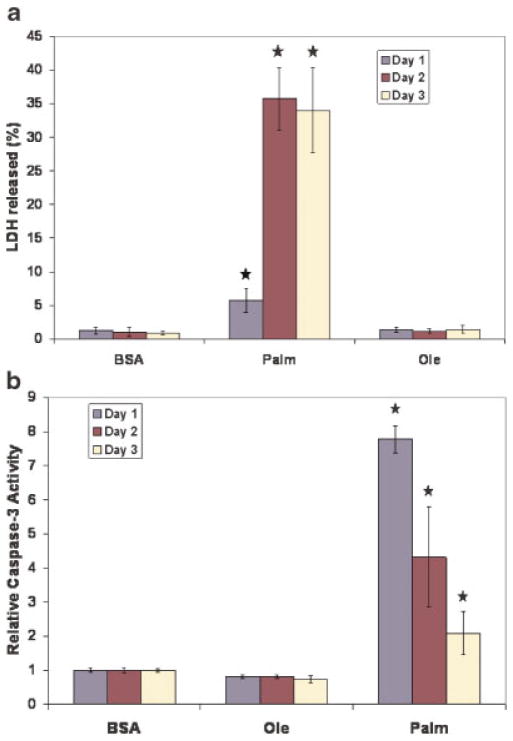

In vivo measurements of hepatotoxicity require measurements of activities of liver-specific enzymes, such as AST and ALT in the serum. Often, a ratio of the activities of ALT/AST is also calculated. However, in vitro, with a single cell type, the cytotoxicity could also be measured by calculating the %LDH activity released. A previous study had compared the three commonly used techniques (AST, ALT, and LDH release) and found that LDH assay was more sensitive than the other two. Very good correlation (Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.95) was found between the LDH and ALT assay (Wolf et al., 1998). Many previous studies (Li et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2002) indeed have used this assay to characterize hepatocellular toxicity in vitro. Therefore, in the current study, the cytotoxicity of the FFAs was measured as %LDH released. The saturated FFA, palmitate was found to be toxic and its toxicity increased significantly on the second day of exposure and remained elevated on the third day, while the unsaturated FFA was not toxic (Fig. 1a). In addition, exposure to palmitate led to a significant increase in caspase-3 activity (Fig. 1b) indicating initiation of apoptosis in the cells exposed to palmitate and further corroborating the LDH release results.

Figure 1.

Cytotoxicity of palmitate. a: Measurement of LDH release. Confluent HepG2 cells were treated with 0.7 mM palmitate or oleate complexed to 4% BSA. Control cells were treated with just 4% BSA. Media were changed every 24 h. The cytotoxicity was measured as %LDH released after every 24 h exposure, as explained in the Section “Materials and Methods.” Data presented as the percent of total LDH released each day, as mean ± s.d. of n =9 experiments. b: Measurement of caspase-3 activation. Cells were treated as in (a) and the activity of caspase-3 was measured using a fluorimetric assay. Data presented as caspase-3 activity ± s.d. relative to the control of n =9 from three independent experiments. [Color figure can be seen in the online version of this article, available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Since the cytotoxicity of palmitate did not change much from Days 2 to 3, most of the experimental verifications were conducted for 2 days. Furthermore, it was found that the treatments effective on Day 2 were equally effective on Day 3 and thus the results, herein, were reported for 2 days.

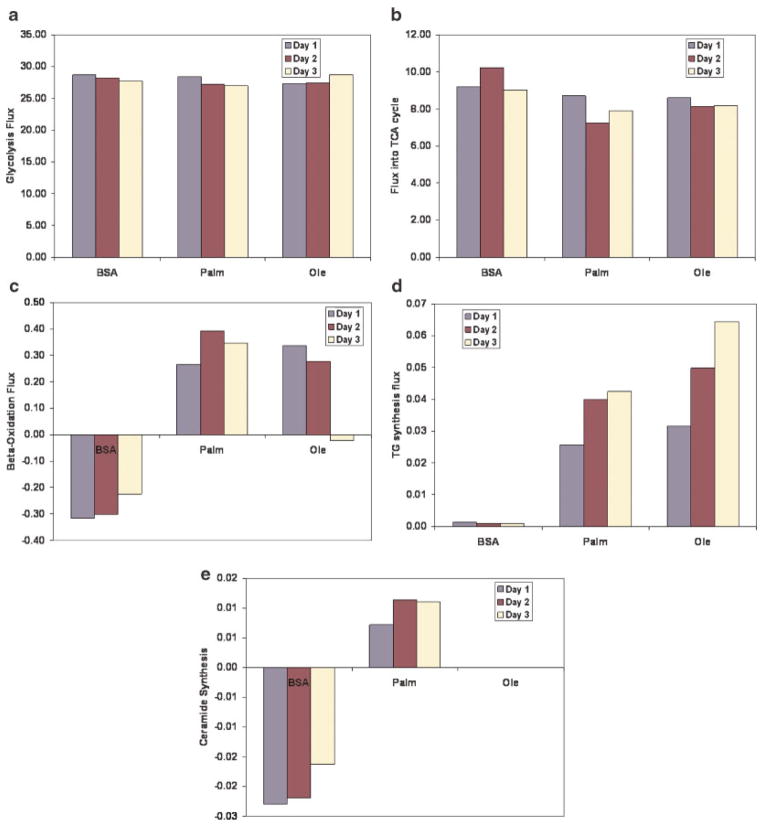

MFA and Correlation Analysis

Figure 2a–e show the fluxes of the major pathways of the cells as calculated by the MFA. For a complete list of the flux values, see Tables ST5–ST7 and Figure SF2 in the Supplementary file. No significant change in the glycolytic flux was observed upon the FFA treatment (Fig. 2a), while the flux into the TCA cycle (Fig. 2b) was slightly depressed. Exposure to FFAs led to a significant increase in the fatty acid oxidation flux (Fig. 2c). Note that the flux through the fatty acid oxidation is negative for the control (BSA) case. The negative flux denotes that fatty acid synthesis, and not oxidation, is prevalent in these cells. Exposure to FFAs led to increased intracellular TG accumulation (Fig. 2d). Cells exposed to the unsaturated FFA accumulated greater amount of TG than those exposed to the saturated FFAs (Fig. 2d). Exposure to palmitate led to increased de novo ceramide synthesis as compared to BSA or oleate-treated cells (Fig. 2e). Cells exposed to palmitate also had altered amino acid metabolism. They had, in general, reduced His, Arg, Gly, Cys, Tyr, and Val uptake, but had greater uptake of Ser, Thr, Ile, Leu, and Phe than controls (BSA-treated cells). Among these, Phe, Val, Tyr, Thr, Ile, His, Arg, and Leu are essential amino acids while Gly and Cys are required for GSH synthesis. Palmitate-treated cells also secreted less Ala compared to controls. Most of these differences in amino acid uptake/release were also observed when palmitate-treated cells were compared to oleate-treated cells. Some of the fluxes altered by exposure to palmitate were chosen for further analysis, based on their strong correlation to or known involvement in the toxicity as discussed below. The results of the experiments to evaluate the roles played by these metabolites in the palmitate cytotoxicity are also presented.

Figure 2.

Major fluxes calculated by the MFA. All data in μmol/mg protein/day. a: Glycolysis, (b) flux into TCA cycle, (c) fatty acid beta-oxidation, (d) TG synthesis, and (e) de novo ceramide synthesis. [Color figure can be seen in the online version of this article, available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

In order to gain insights into the fluxes which might contribute to the cytotoxicity, correlation analysis of the calculated fluxes to cytotoxicity was performed. Table I lists various correlation coefficients in decreasing order. It was observed that reactions involved in ketone body production (fluxes 17–20) had the highest positive correlation coefficient to the cytotoxicity. These results suggested a strong relation between cytotoxicity and ketone body production. Serine uptake (flux 28) also had high positive correlation coefficients. Serine is one of the metabolites required for de novo ceramide synthesis. However, most of the serine taken up was oxidized and very little went to the synthesis of de novo ceramide (Tables ST5–ST7 in Supplementary materials section). In fact, the de novo ceramide synthesis (flux 68) had a relatively low (rank 11) correlation to the cytotoxicity.

Table I.

Ranked list of Pearson’s correlation coefficient of the fluxes with cytotoxicity.

| Flux # | Name | Corr. Coeff. |

|---|---|---|

| 18 | Acetoacetyl-CoA → acetoacetate | 0.99 |

| 17 | 2 Acetyl-COA → acetoacetyl-CoA | 0.98 |

| 20 | Acetoacetate + NADH → (B-OH butyrate) | 0.97 |

| 19 | Acac out | 0.97 |

| 28 | Ser (In) | 0.83 |

| 45 | Val (In) | −0.86 |

| 47 | Lys (In) | −0.89 |

| 61 | Lys + 2 aKG + NADPH → 2Glu + acetoacetyl-CoA + 2CO2 + 4 NADH + FADH2 | −0.89 |

| 42 | Cys In | −0.95 |

| 51 | Glu + Cys + Gly → GSH | −0.95 |

Uptake of cysteine (flux 42) and GSH synthesis (flux 51) had the greatest negative coefficient, followed by uptake and metabolism of lysine and valine. These results suggested that supplementation of cysteine could reduce cytotoxicity, which was experimentally validated (see Section “Effects of NAC Supplementation on the Levels of GCS in Palmitate-Treated Cells” below). Exposure to palmitate reduced the uptake of lysine and valine, which are essential fatty acids. Essential fatty acids have been shown to affect cell growth (Gardner and Lane, 1993). Certain studies have also shown protective effects against cell death by supplementing with these amino acids (Hong-Ping and Bao-Shan, 1999).

Experimental Verifications

Fatty Acid Oxidation

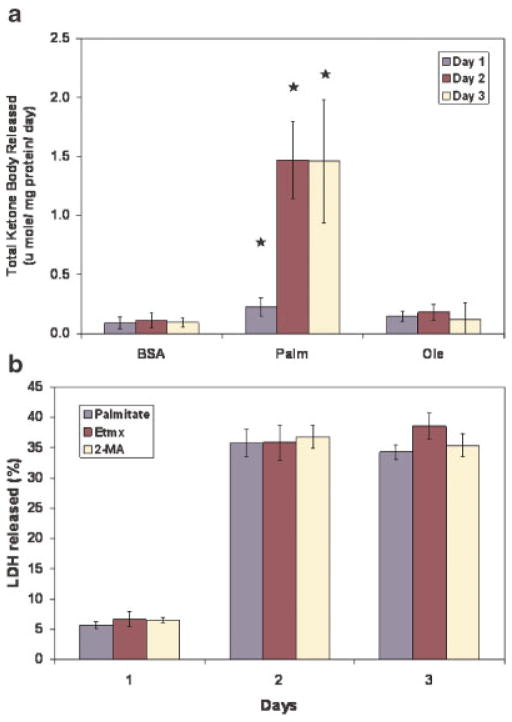

Exposure to palmitate led to a greater release of ketone bodies than the controls or oleate (Fig. 3a). The fluxes of ketone body production had the highest Pearson’s correlation coefficient to the cytotoxicity (see Table I). In order to test a causative role of increased oxidation in the cytotoxicity, the effect of inhibitors of beta-oxidation, etomoxir (Etmx) and 2-mercaptoacetate (2-MA), was tested. Etmx inhibits carnitine palmitoyl transferase (CPT) (Minnich et al., 2001), while 2-MA inhibits long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase activity (Bauché et al., 1981). Etmx treatment has been shown to completely inhibit beta-oxidation of palmitate in HepG2 cells (Minnich et al., 2001). Multiple concentrations of these inhibitors (20, 50, and 100 μM) were tested for their ability to reduce the cytotoxicity. However, inhibiting FFA oxidation did not reduce the cytotoxicity (Fig. 3b). This suggested that the increased beta-oxidation of palmitate, despite its strong correlation, was not responsible for the cytotoxicity of the FFA.

Figure 3.

Ketone body release. Confluent HepG2 cells were treated with 0.7 mM palmitate or oleate complexed to 4% BSA. Media were replaced daily. a: Oxidation of the FFAs. The fluxes of acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate release were measured for each day. Sum of the acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate release is presented as the total ketone body released. b: Effect of inhibition of beta-oxidation on the FFA-toxicity. Cells were treated with palmitate in the presence of 100 μM Etmx or 100 μM 2-MA and the LDH released was measured. For figures (a) and (b), data are presented as mean ± s.d. of n = 9 from three independent experiments. *, Significantly higher than control, P <0.01. [Color figure can be seen in the online version of this article, available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

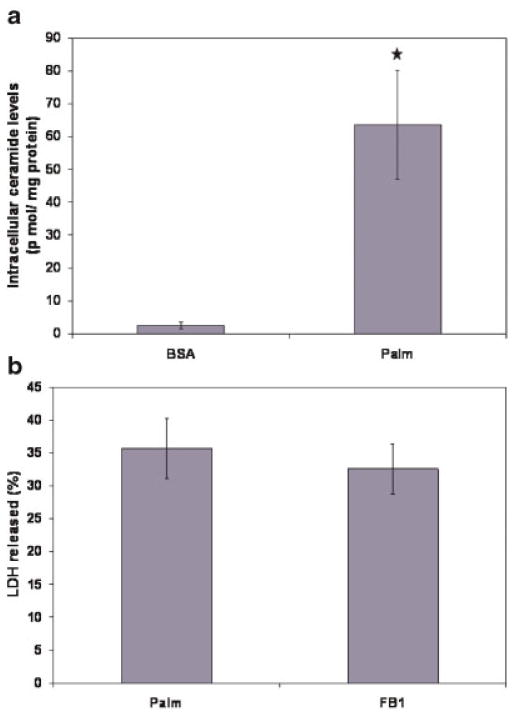

De Novo Ceramide Synthesis

Because de novo ceramide synthesis has been suggested as an important player in the cytotoxicity of saturated FFAs, the fluxes of de novo ceramide synthesis were calculated in the various treatments. Cells treated with saturated FFA had increased flux through de novo ceramide synthesis (Fig. 2f) as well as higher intracellular levels of ceramide (Fig. 4a). Sensitivity analysis revealed that ceramide synthesis in palmitate-treated cells was more sensitive to changes in the uptake of palmitate than serine (Figure SF3a in the Supplementary section). In order to test the role of increased de novo ceramide synthesis on the cytotoxicity, we tested the effect of an inhibitor of de novo ceramide synthesis, fumonisin B1 (FB1), on the cytotoxicity. The inhibitor reduced the accumulation of ceramide by about 72% (See Figure SF3b in the Supplementary section), but did not reduce the cytotoxicity of the FFA (Fig. 4c). These results suggested that de novo ceramide synthesis does not play a significant role in the palmitate-induced toxicity of HepG2 cells.

Figure 4.

Role of de novo ceramide synthesis in the cytotoxicity. a: Intracellular accumulation of ceramide in response to palmitate. Cells were treated with 0.7 mM palmitate for 48 h and the cellular ceramide levels were measured using LC/MS. b: Effect of inhibitor of de novo ceramide synthesis on the cytotoxicity of palmitate. Cells were treated with palmitate in presence of 20 μM FB1 and the cytotoxicity after 48 h of treatment was measured. Data presented as mean ± s.d. of n = 9 from three independent experiments. [Color figure can be seen in the online version of this article, available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

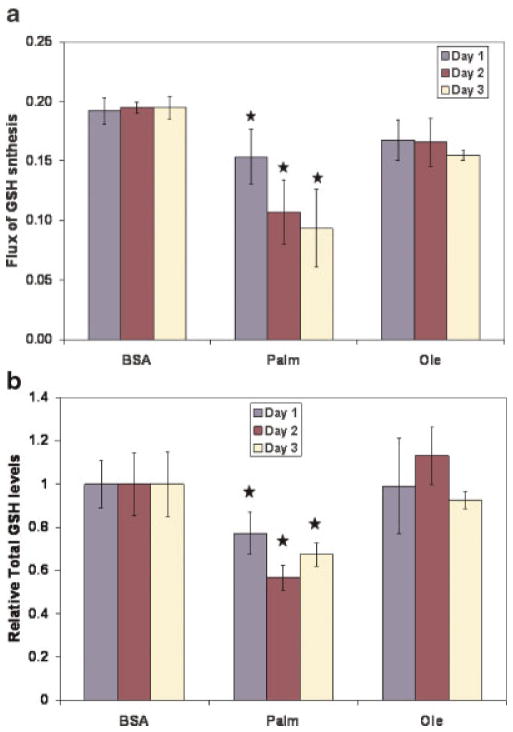

Glutathione (GSH) Synthesis

Oxidative stress is considered an important factor in the development of NASH. We have previously identified an important role of oxidative stress in the toxicity of palmitate (Srivastava and Chan, 2007). GSH is the primary anti-oxidant molecule of the cell and protects cells against oxidative insults. Palmitate treatment was associated with consistently reduced flux through GSH synthesis (Fig. 5a). In order to test the predicted reduction in the GSH synthesis, the total GSH (GSH + GSSG) levels in the cells were measured. The total GSH (tGSH) levels were measured because they are resistant to oxidative stress (Glosli et al., 2002). Exposure to palmitate was associated with reduced levels of tGSH (Fig. 5b). In silico sensitivity studies identified that the GSH synthesis was limited primarily by the supply of cysteine (Fig. 5c). It was also observed that exposure to palmitate led to reduced cysteine uptake (see Tables ST5–ST7 in Supplementary file), suggesting that it may be the limiting amino acid. To further identify what limits the GSH synthesis, the expressions of the rate-limiting enzyme of GSH synthesis and the cystine transporter were measured. GCS is the first and rate-limiting enzyme of GSH synthesis and catalyzes the formation of the peptide bond between glutamate and cysteine. Another important regulator of GSH synthesis is the availability of cysteine, the primary source of which is cystine in the medium. Cystine is taken up through a transporter, the system Xc- (Anderson and Meister, 1987), which is composed of two proteins—xCT and 4F2hc/CD98. Western blot analyses revealed that the expression of GCS was increased (Fig. 5d), while that of xCT was decreased (Fig. 5e) significantly in palmitate-treated cells. Both these proteins were altered in a time-dependent manner, that is, the change was greater on Day 2 than on Day 1. These results identified that the reduced GSH synthesis in palmitate-treated cells was due to lower cystine uptake caused by reduced levels of the transporter and was not regulated by the levels of GCS. These studies, in conjunction with the sensitivity studies, indicated that increasing intracellular cysteine availability could increase GSH synthesis and thus, may reduce cytotoxicity, while supplementing glycine would not significantly affect the GSH levels or cytotoxicity. Because palmitate treatment reduced the expression of the system xCT (Fig. 5e), we would not expect that supplementing with cystine would be protective. Indeed, externally added cysteine (100 μM to 10 mM), which rapidly converts to cystine in solution (Lu, 1999), was unable to reduce the toxicity of palmitate (data not shown). In contrast, uptake of NAC is independent of the levels of system Xc- (Sato et al., 2005). NAC supplementation has been shown to increase the cellular GSH levels in HepG2 cells (Greutter and Lemke, 1985). The supplementation of NAC significantly reduced the cytotoxicity of the FFA (Fig. 5f), while supplementation of glycine had no effect (not shown). Thus, the MFA and the perturbation studies provided information about the perturbations in the GSH metabolism induced by palmitate which were corroborated by Western blots. Together, these studies provided insights on how to modulate palmitate toxicity.

Figure 5.

Regulation of GSH metabolism. a: The flux through the synthesis of GSH calculated by the MFA model. b: Relative levels of total GSH in the cells. At the end of desired exposure times, cells were harvested and the tGSH in the cells was measured colorimetrically. The data was normalized to cellular protein levels, measured using BCA assay. Data presented as mean ± s.d. of three independent experiments. c: Sensitivity analysis of the effect of increased flux of the amino acids on the flux of GSH synthesis. d: Expression of gamma GCS (heavy subunit, GCS). Cells were exposed to BSA, palmitate or oleate for 24 and 48 h, following which cells were lyzed and the expression of GCS were measured using Western blot. The details of the Western blot analyses are provided in the methods section. Beta-actin was employed as the loading control. e: Effect of treatments on the levels of xCT subunit of the cystine transporter system Xc-. Cells were exposed to BSA, palmitate or oleate for 24 and 48 h, following which cells were lyzed and the expression of xCT was measured using Western blot. The details of the Western blot analyses are provided in the methods section. Beta-actin was employed as the loading control. f: Effect of NAC supplementation on cytotoxicity. The cells were treated with 0.7 mM palmitate in the presence or absence of 10 mM NAC for 2 days and the LDH released after 48 h of treatments were measured. Data presented as mean ± s.d. of n =9 from three independent experiments. *, Significantly higher than control, P <0.01. [Color figure can be seen in the online version of this article, available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

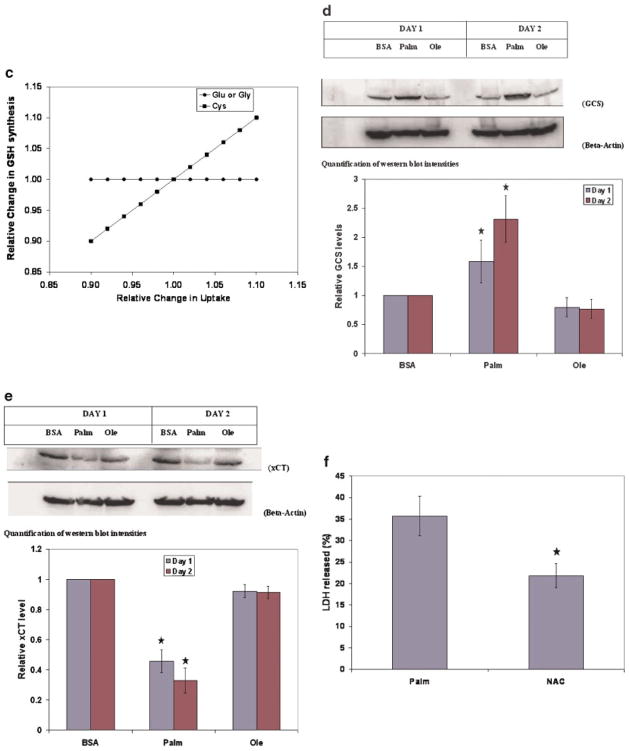

Effects of NAC Supplementation on the Levels of GCS in Palmitate-Treated Cells

Previous studies have suggested that oxidative stress or cysteine limitation increases the levels of GCS (Lu, 1999). Our study shows that exposure to palmitate produces both oxidative stress and cysteine limitation. Thus, it is likely that the increase in GCS levels in palmitate-treated cells was due to reduced cysteine availability and/or oxidative stress. NAC supplementation increases the intracellular cysteine (Anderson and Meister, 1987) and GSH levels (Greutter and Lemke, 1985) and reduces oxidative stress (Qanungo et al., 2004). The effects of NAC supplementation in the palmitate-treated cells were studied to identify whether the increase in the GCS was mediated by oxidative stress. Exposure to NAC led to increased levels of GCS on Day 1, but reduced levels on Day 2 (Fig. 6). This suggested that chronic (>24 h), but not acute exposure to palmitate increased GCS levels by reducing cysteine levels and/or causing oxidative stress.

Figure 6.

Effect of NAC supplementation on GCS levels in palmitate-treated cells. Cells were treated with increasing amounts of NAC (0, 1, 5, and 10 mM) for 48 h in palmitate medium. Media were changed every 24 h. At the end of every 24 h, the expression of GCS was measured using Western blots. [Color figure can be seen in the online version of this article, available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Discussion

While it is known that altered metabolism and generation of ROS play important roles in the development of hepatic lipotoxicity, the underlying global metabolic responses are not clearly known. MFA of human hepatoma cells in response to various FFAs identified changes in the intracellular fluxes in response to the different FFAs and helped to differentiate between the potential mechanisms involved in the cytotoxicity of the saturated FFAs as compared to the unsaturated FFAs. Additionally, MFA also identified those external fluxes which regulate the internal fluxes of interest, thus suggesting possible supplementations to regulate the lipotoxicity.

We have previously identified that the exposure to palmitate causes significant oxidative stress, which plays an important role in the toxicity of this fatty acid (Srivastava and Chan, 2007). Oxidative stress has been suggested to play an important role in the development of various obesity-related disorders such as type 2 diabetes (Kaneto et al., 2007) and NASH (McCullough, 2006). GSH is the primary anti-oxidant thiol. Under conditions of oxidative stress, the role of GSH becomes increasingly important. Not only does it act as a ROS scavenger, but is also central to cellular detoxification of toxic metabolites through the GSH-S-transferases (GSTs).

Many studies have identified reduced GSH levels in the livers of obese patients (Carmiel-Haggai et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2004; Mandato et al., 2005). However, the underlying mechanisms of reduced GSH levels in obesity are not clear. In this study we found that palmitate reduces the synthesis of GSH by reducing cysteine uptake, at least in part by reducing the levels of the cysteine transporter xCT. These results indicate a multi-pronged effect of palmitate on the cellular redox homeostasis which leads to the cytotoxicity of this fatty acid. The underlying mechanism in the reduction of xCT expression by palmitate is unknown, but may provide important insights into the oxidative stress caused by exposure to this FFA. It was also identified that the GSH synthesis was not limited by the levels of GCS, the first and rate-limiting enzyme of GSH synthesis. In fact, the expression of GCS was found to be increased in the palmitate-treated cells, in a time-dependent fashion. However, NAC supplementation did not reduce the acute increase in GCS expression in response to palmitate, suggesting that the acute increase by palmitate may not be mediated by oxidative stress or cysteine limitation but perhaps through the activation of certain transcription factors involved in regulating GCS expression, for example, Nrf2 (Wild et al., 1999). However, the reduction in GCS levels in palmitate-treated cells by chronic (48 h) treatment of NAC suggests that the chronic increase in GCS by palmitate (which was much greater than the acute increase in response to palmitate) was, indeed, mediated through a reduction in cysteine supply and/or oxidative stress.

A lack of involvement of de novo ceramide synthesis in the toxicity of palmitate was observed despite increased de novo ceramide synthesis and ceramide accumulation in the palmitate-treated cells. In fact, studies by other groups have also indicated that saturated FFA-toxicity to hepatocytes is independent of de novo ceramide synthesis (Feldstein et al., 2006; Wei et al., 2006). In our study, the ceramide accumulation was in picomoles/milligrams protein, while the flux of synthesis and metabolism of ceramide were in nanomoles/milligrams protein. This indicates that these cells, and probably hepatocytes in general, can effectively metabolize ceramide such that the accumulations do not reach cytotoxic levels.

This study demonstrates the applicability of MFA in identifying the altered metabolic processes under simulated conditions of metabolic disorders. The results show differential metabolism of saturated versus unsaturated FFAs, which results in the toxic effect of the former and suggest potential treatments to reduce the saturated FFA toxicity. MFA identified more than one cellular process to be altered, suggesting targets for further study.

The MFA study indicated the complex metabolic alterations induced by FFAs were caused, in part, by changes in the levels of proteins (e.g., xCT), leading to altered physiological response (cytotoxicity). Similarly, exposure to FFAs could alter various other cellular processes which may not cause a significant change in metabolism, but still initiate cell death, for example, the activities of certain signaling pathways may be regulated by palmitoylation (Resh, 2006) as well as affect the transcription of genes involved in multiple cellular processes (Swagell et al., 2005). Though, these processes were not investigated in this study, a more complete understanding of the development of lipotoxicity requires generation and integration of such multi-source information. Application of novel high throughput techniques coupled with advanced modeling would help in achieving this goal. Such analysis would provide important insights into the underlying changes, as well as novel information into the inter-relationships among the changes, thus providing more effective alternatives to regulate the deleterious effects of FFAs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Science Foundation

Contract grant number: 0331297; 0425821

Contract grant sponsor: National Institute of Health

Contract grant number: 1R01GM079688-01

Contract grant sponsor: Environmental Protection Agency

Contract grant sponsor: MSU Foundation

Contract grant sponsor: Whitaker Foundation

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Material available at http://www.interscience.wiley.com/jpages/0006-3592/suppmat.

References

- Anderson ME, Meister A. Intracellular delivery of cysteine. Methods Enzymol. 1987;143:313–326. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)43059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angulo P, Lindor KD. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17(Supp l):S186–S190. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.17.s1.10.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banta S, Yokoyama T, Berthiaume F, Yarmush ML. Quantitative effects of thermal injury and insulin on the metabolism of the skeletal muscle using the perfused rat hindquarter preparation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;88(5):613–629. doi: 10.1002/bit.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauché F, Sabourault D, Giudicelli Y, Nordmann J, Nordmann R. 2-Mercaptoacetate administration depresses the beta-oxidation pathway through an inhibition of long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase activity. Biochem J. 1981;15; 196(3):803–809. doi: 10.1042/bj1960803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, Nuremberg P, Horton JD, Cohen JC, Grundy SM, Hobbs HH. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: Impact of ethnicity. Hepatology. 2004;40(6):1387–1395. doi: 10.1002/hep.20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmiel-Haggai M, Cederbaum AI, Nieto N. A high-fat diet leads to the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese rats. FASEB J. 2005;19(1):136–138. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2291fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan C, Berthiaume F, Lee K, Yarmush ML. Metabolic flux analysis of cultured hepatocytes exposed to plasma. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2003;81(1):33–49. doi: 10.1002/bit.10453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan C, Berthiaume F, Lee K, Yarmush ML. Metabolic flux analysis of hepatocyte function in hormone- and amino acid-supplemented plasma. Metab Eng. 2003;5(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/s1096-7176(02)00011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daae EB, Ison AP. Classification and sensitivity analysis of a proposed primary metabolic reaction network for Streptomyces Lividans. Metab Eng. 1999;1:153–165. doi: 10.1006/mben.1998.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashti N, Feng Q, Freeman MR, Gandhi M, Franklin FA. Trans polyunsaturated fatty acids have more adverse effects than saturated fatty acids on the concentration and composition of lipoproteins secreted by human hepatoma HepG2 cells. J Nutr. 2002;132(9):2651–2659. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.9.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominy JE, Hwang J, Stipanuk MH. Overexpression of cysteine dioxygenase (CDO) reduces intracellular cysteine and glutathione pools in HepG2/C3A Cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293(1):E62–69. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00053.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essington TE. Development and sensitivity analysis of bioenergetics models for Skipjack Tuna and Albacore: A comparison of alternative life histories. Trans Am Fish Soc. 2003;132:759–770. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell GC, Larter CZ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: From steatosis to cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2006;43(2 Suppl 1):S99–S112. doi: 10.1002/hep.20973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein AE, Werneburg NW, Li Z, Bronk SF, Gores GJ. Bax inhibition protects against free fatty acid-induced lysosomal permeabilization. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290(6):G1339–G1346. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00509.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiskerstrand T, Refsum H, Kvalheim G, Ueland PM. Homocysteine and other thiols in plasma and urine: automated determination and sample stability. Clin Chem. 1993;39(2):263–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furth EE, Sprecher H, Fisher EA, Fleishman HD, Laposata M. An in vitro model for essential fatty acid deficiency: HepG2 cells permanently maintained in lipid-free medium. J Lipid Res. 1992;33(11):1719–1726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DK, Lane M. Amino acids and ammonium regulate mouse embryo development in culture. Biol Reprod. 1993;48(2):377–385. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod48.2.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons GF, Khurana R, Odwell A, Seelaender MC. Lipid balance in HepG2 cells: Active synthesis and impaired mobilization. J Lipid Res. 1994;35(10):1801–1808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glosli H, Tronstad KJ, Wergedal H, Muller F, Svardal A, Aukrust P, Berge RK, Prydz H. Human TNF-alpha in transgenic mice induces differential changes in redox status and glutathione-regulating enzymes. FASEB J. 2002;16(11):1450–1452. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0948fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greutter CA, Lemke SM. Dissociation of cysteine and glutathione levels from nitroglycerin-induced relaxation. Eur J Pharmacol. 1985;111:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Huang N, Cai J, Xie W, Hamilton JA. Fatty acid transport and metabolism in HepG2 cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290(3):G528–G534. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00386.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong-Ping G, Bao-Shan KU. Neuroprotective effect of L-lysine monohydrochloride on acute iterative anoxia in rats with quantitative analysis of electrocorticogram. Life Sci. 1999;65(2):PL19–PL25. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt NB. Hep G2 cells as a resource for metabolic studies: Lipo-protein, cholesterol, and bile acids. FASEB J. 1990;4:161–168. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.2.2153592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneto H, Katakami N, Kawamori D, Miyatsuka T, Sakamoto K, Matsuoka TA, Matsuhisa M, Yamasaki Y. Involvement of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of diabetes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;1(4):165–174. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Sohn I, Ahn JI, Lee KH, Lee YS, Lee YS. Hepatic gene expression profiles in a long-term high-fat diet-induced obesity mouse model. Gene. 2004;340(1):99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BJ, Forbes NS. Flux analysis shows that hypoxia-inducible-factor-1-alpha minimally affects intracellular metabolism in tumor spheroids. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2006;96(6):1167–1182. doi: 10.1002/bit.21205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krohn M, Reidy S, Kerr S. Bioenergetic analysis of the effects of temperature and prey availability on growth and condition of northern cod (Gadus morhua) Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 1997;54(Suppl 1):113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kosone T, Takagi H, Horiguchi N, Ariyama Y, Otsuka T, Sohara N, Kakizaki S, Sato K, Mori M. HGF ameliorates a high-fat diet-induced fatty liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293(1):G204–210. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00021.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Berthiaume F, Stephanopoulos GN, Yarmush ML. Profiling of dynamic changes in hypermetabolic livers. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2003;83(4):400–415. doi: 10.1002/bit.10682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelliott CJ, Lopez M, Curtis RK, Parker N, Laudes M, Yeo G, Jimenez-Linan M, Grosse J, Saha AK, Wiggins D, Hauton D, Brand MD, O’Rahilly S, Griffin JL, Gibbons GF, Vidal-Puig A. Transcript and metabolite analysis of the effects of tamoxifen in rat liver reveals inhibition of fatty acid synthesis in the presence of hepatic steatosis. FASEB J. 2005;19(9):1108–1119. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3196com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Li LJ, Chao HC, Yang Q, Liu XL, Sheng JF, Yu HY, Huang JR. Isolation and short term cultivation of swine hepatocytes for bioartificial liver support system. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2005;4(2):249–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu SC, Huang HY. Comparison of sulfur amino acid utilization for GSH synthesis between HepG2 cells and cultured rat hepatocytes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;47(5):859–869. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90486-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu SC. Regulation of hepatic glutathione synthesis: Current concepts and controversies. FASEB J. 1999;13(10):1169–1183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhi H, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Gores GJ. Free fatty acids induce JNK-dependent hepatocyte lipoapoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(17):12093–12101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510660200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandato C, Lucariello S, Licenziati MR, Franzese A, Spagnuolo MI, Ficarella R, Pacilio M, Amitrano M, Capuano G, Meli R, Vajro P. Metabolic, hormonal, oxidative, and inflammatory factors in pediatric obesity-related liver disease. J Pediatr. 2005;147(1):62–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough AJ. Pathophysiology of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(3 Suppl 1):S17–S29. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000168645.86658.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnich A, Tian N, Byan L, Bilder G. A potent PPARalpha agonist stimulates mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation in liver and skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280(2):E270–E279. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.2.E270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muto Y, Gibson DM. Selective dampening of lipogenic enzymes of liver by exogenous polyunsaturated fatty acids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1970;38(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)91076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen C. An enzymatic fluorimetric micromethod for the determination of acetoacetate, hydroxybutyrate, pyruvate and lactate. Clin Chim Acta. 1971;33(2):293–300. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(71)90486-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qanungo S, Wang M, Nieminen AL. N-acetyl-L-cysteine enhances apoptosis through inhibition of nuclear factor-{kappa}B in hypoxic murine embryonic fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(48):50455–50464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406749200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resh MD. Palmitoylation of ligands, receptors, and intracellular signaling molecules. Sci STKE. 2006;359:re14. doi: 10.1126/stke.3592006re14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai T, Kamanna S, Kashyap ML. Niacin, but not gemfibrozil, selectively increases LP-AI, a cardioprotective subfraction of HDL, in patients with low HDL-cholesterol. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1783–1789. doi: 10.1161/hq1001.096624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Shiiya A, Kimata M, Maebara K, Tamba M, Sakakura Y, Makino N, Sugiyama F, Yagami K, Moriguchi T, Takahashi S, Bannai S. Redox imbalance in cystine/glutamate transporter-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(45):37423–37429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506439200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheen AJ, Luyckx FH. Obesity and liver disease. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;16(4):703–716. doi: 10.1053/beem.2002.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimabukuro M, Zhou YT, Levi M, Unger RH. Fatty acid-induced beta cell apoptosis: A link between obesity and diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(5):2498–2502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S, Chan C. Hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals mediate palmitate-induced cytotoxicity to hepatoma cells: Relation to mitochondrial permeability transition. Free Radic Res. 2007;41(1):38–49. doi: 10.1080/10715760600943900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steegborn C, Clausen T, Sondermann P, Jacob U, Worbs M, Marinkovic S, Huber R, Wahl MC. Kinetics and inhibition of recombinant human cystathionine gamma-lyase. Toward the rational control of transsulfuration. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(18):12675–12684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss JG, Hayn M, Zechner R, Levak-Frank S, Frank S. Fatty acids liberated from high-density lipoprotein phospholipids by endothelial-derived lipase are incorporated into lipids in HepG2 cells. Biochem J. 2003;371(Pt 3):981–988. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swagell CD, Henly DC, Morris CP. Expression analysis of a human hepatic cell line in response to palmitate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328(2):432–441. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A, Xia T, Ran P, Chen X, Nuessler AK. Qualitative study of three cell culture methods. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2002;22(4):288–291. doi: 10.1007/BF02896766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Wang D, Topczewski F, Pagliassotti MJ. Saturated fatty acids induce endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis independently of ceramide in liver cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291(2):E275–E281. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00644.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild AC, Moinova HR, Mulcahy RT. Regulation of gamma—glutamylcysteine synthetase subunit gene expression by the transcription factor Nrf2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(47):33627–33636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf A, Schramm U, Fahr A, Aicher L, Cordier A, Trommer WE, Fricker G. Hepatocellular effects of cyclosporine A and its derivative SDZ IMM 125 in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284(3):817–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.