Summary

The objective of this study was to test the hypotheses that (1) the steady-state friction coefficient of articular cartilage is significantly smaller under cyclical compressive loading than the equilibrium friction coefficient under static loading, and decreases as a function of loading frequency; (2) the steady-state cartilage interstitial fluid load support remains significantly greater than zero under cyclical compressive loading and increases as a function of loading frequency. Unconfined compression tests with sliding of bovine shoulder cartilage against glass in saline were carried out on fresh cylindrical plugs (n=12), under three sinusoidal loading frequencies (0.05 Hz, 0.5 Hz and 1 Hz) and under static loading; the time-dependent friction coefficient μeff was measured. The interstitial fluid load support was also predicted theoretically. Under static loading μeff increased from a minimum value (μmin=0.005±0.003) to an equilibrium value (μeq=0.153±0.032). In cyclical compressive loading tests μeff similarly rose from a minimum value (μmin=0.004±0.002, 0.003±0.001 and 0.003±0.001 at 0.05, 0.5 and 1 Hz) and reached a steady-state response oscillating between a lower-bound (μlb=0.092±0.016, 0.083±0.019 and 0.084±0.020) and upper bound (μub=0.382±0.057, 0.358±0.059, and 0.298±0.061). For all frequencies it was found that and μub> μeq and μlb < μeq (p<0.05). Under cyclical compressive loading the interstitial fluid load support was found to oscillate above and below the static loading response, with suction occurring over a portion of the loading cycle at steady-state conditions. All theoretical predictions and most experimental results demonstrated little sensitivity to loading frequency. On the basis of these results, both hypotheses were rejected. Cyclical compressive loading is not found to promote lower frictional coefficients or higher interstitial fluid load support than static loading.

Keywords: Cartilage, dynamic loading, friction coefficient, interstitial fluid pressurization

Introduction

Articular cartilage functions as the bearing material between opposing articular surfaces of diarthrodial joints. Previous frictional studies have found that articular cartilage can have very low friction coefficients upon loading (0.002 to 0.02) (Jones, 1934, 1936; Charnley, 1959; McCutchen, 1959; Charnley, 1960; Barnett and Cobbold, 1962; Linn, 1967; Linn and Radin, 1968; Unsworth et al., 1975; Malcom, 1976; Forster and Fisher, 1996; Krishnan et al., 2003). But with a step load of constant magnitude (static load) applied for several hours, the coefficient becomes quite elevated (0.1–0.6) (McCutchen, 1962; Malcom, 1976; Forster and Fisher, 1996; Ateshian et al., 1998; Forster and Fisher, 1999; Krishnan et al., 2004). It has been proposed by McCutchen (McCutchen, 1959, 1962) and supported by others (Malcom, 1976; Macirowski et al., 1994; Forster and Fisher, 1996; Ateshian et al., 1998) that this transient frictional behavior is related to the fluid pressurization in the tissue. Under this hypothesis, by load transfer from the solid to the fluid phase, the interstitial fluid is able to substantially reduce the friction coefficient. When the interstitial fluid pressure within the tissue subsides to zero, the frictional coefficient reaches an equilibrium value.

Experimental measurements of the interstitial fluid pressurization of articular cartilage (Oloyede, 1991; Soltz and Ateshian, 1998, 2000a; Park et al., 2003) have confirmed theoretical predictions (Ateshian et al., 1994; Macirowski et al., 1994; Ateshian and Wang, 1995; Kelkar and Ateshian, 1999) that the load supported by interstitial fluid can be in excess of 90% of the total applied load immediately upon loading, though it subsides to zero under prolonged static loading. In our recent study where measurements of cartilage interstitial fluid pressurization were performed simultaneously with frictional measurements against glass under a constant applied load (Krishnan et al., 2004), a linear correlation with a negative slope was observed between the friction coefficient and interstitial fluid load support, strongly supporting the hypothesis that interstitial fluid pressurization is a primary regulator of the frictional response of cartilage.

Under static loading, in laboratory conditions, the equilibrium cartilage friction coefficient achieved when fluid pressurization has subsided (μeq ~0.1–0.6) is typically too high to provide functionally effective lubrication. For example, if the peak load transmitted across the hip joint during gait is approximately five times normal body weight (~5×750 N = 3,750 N), this would result in friction forces ranging between 375 and 2,250 N. Such elevated friction forces can lead to rapid wear and degeneration of the surfaces (Forster and Fisher, 1996). It is therefore expected that the normal environment in diarthrodial joints would maintain the friction coefficient in a low range (e.g., ~0.02 or less) over the range of activities of daily living. This study begins to address the question of what makes the friction coefficient stay sufficiently low under physiological loading conditions in vivo.

Under physiological activities such as walking and running, the loading environment in the lower extremities is cyclical (Dillman, 1975; Paul and McGrouther, 1975), yet few studies have investigated the frictional characteristics of articular cartilage under such conditions. Malcom observed that the effect of dynamic loading compared to static loading was to reduce the friction coefficient of cartilage and keep it lower over a wider range of normal stresses (Malcom, 1976). Results from our previous measurements of interstitial fluid load support under dynamic confined compression loading (Soltz and Ateshian, 2000a) indicate that substantial interstitial fluid pressurization persists at frequencies as low as 10−4 Hz. Based on these observations, the hypothesis of the current study is that under cyclical loading rates and physiological stresses, normal articular cartilage always maintains high interstitial fluid load support and low friction coefficient, never achieving the zero-pressure/high friction equilibrium conditions typical of prolonged static loading under laboratory conditions. More specifically, (1) the steady-state friction coefficient is significantly smaller under cyclical compressive loading than the equilibrium friction coefficient under static loading, and decreases as a function of loading frequency; (2) the steady-state interstitial fluid load support remains significantly greater than zero under cyclical compressive loading and increases as a function of loading frequency. These hypotheses are tested using a combination of experimental and theoretical studies.

Materials and Methods

In the experimental study, friction measurements between bovine articular cartilage and glass were performed in unconfined compression under three dynamic loading frequencies representative of physiological conditions (0.05 Hz, 0.5 Hz and 1 Hz), and under a static load. In the theoretical study, cartilage interstitial fluid load support was predicted under similar conditions of static and dynamic loading, using the previously described biphasic-CLE (Conewise Linear Elasticity) mixture model of articular cartilage (Mow et al., 1980; Curnier et al., 1995; Soltz and Ateshian, 2000b). From these theoretical analyses, the frictional response was also predicted using our recently validated biphasic boundary lubrication model (Ateshian et al., 1998; Krishnan et al., 2004). Results from the theoretical study were used to help interpret the experimental results.

Specimen Preparation

Fresh bovine shoulder joints were obtained from a local abattoir on the day of slaughter (3 joints, ages 1–3 months). Joints were never frozen but stored at 4°C with an intact capsule, for no more than four days prior to dissection. Following joint dissection, four full thickness osteochondral plugs (Ø8 mm) were harvested from each humeral head (n=12). Underlying bone and vascularized tissue (~400 microns thick) were removed from the deep zone of the cartilage plugs (final thickness 2.1±0.43 mm) using a sledge microtome (model 1400; Leitz, Rockleigh, NJ), leaving the articular surface intact. Smaller diameter cylindrical plugs (Ø4.8 mm) were cored out from the microtomed samples in order to obtain a uniform cross-section.

Friction Apparatus

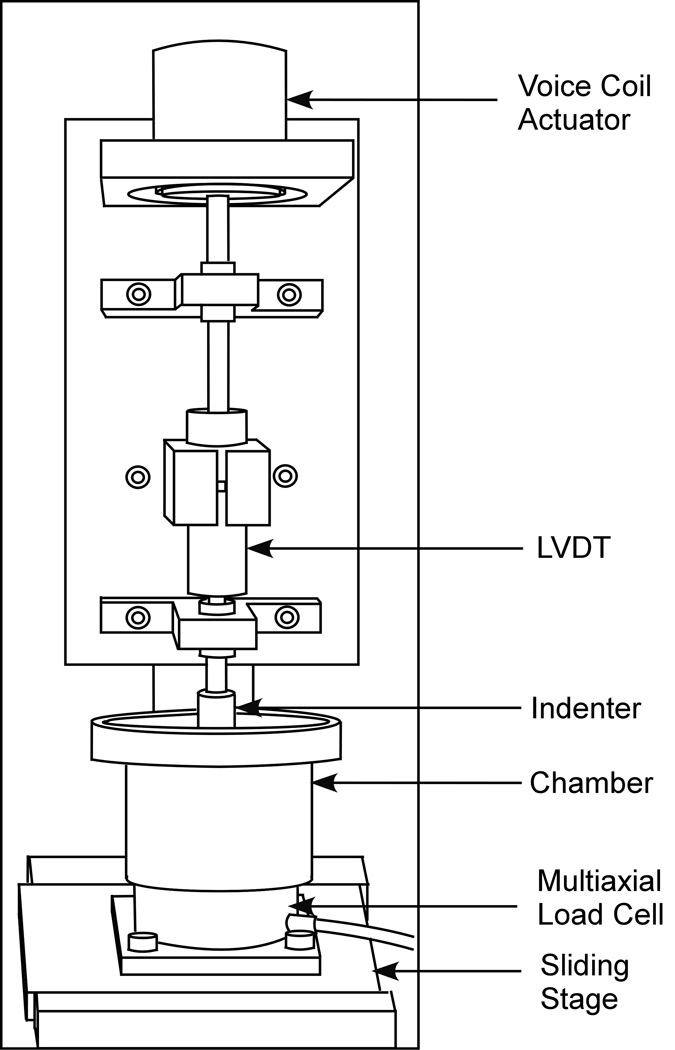

The friction coefficient between cartilage and glass was measured in a phosphate buffered saline (PBS) bath, under the configuration of unconfined compression, with continuous reciprocal sliding (sliding velocity = 1 mm/s, range of translation = ± 4.5 mm). Sliding motion was provided by a computer controlled translation stage (Model PM500-1L, Newport Corporation, CA). Static and sinusoidal loading was applied using a voice-coil load actuator (Model LA17-28-000A, BEI Kimco Magnetics Division, CA) under load control. Normal and frictional loads were measured with a multi-axial load cell mounted on the translation stage (Model 20E12A-M25B, JR3 Inc., CA). Cartilage axial deformation was monitored with a linear variable differential transformer (HR100, Shaevitz Sensors, VA), connected in series with the loading platen (Figure 1). The normal force, frictional force and axial deformation were monitored throughout the test with data acquisition hardware and software (PCI-MIO-16XE & Labview v6.1; National Instruments, Austin, TX). All tests were terminated after 2,500 seconds. The time-dependent friction coefficient, μeff, was calculated from the ratio of the friction force to the normal force. The minimum value of μeff was denoted by μmin. Under static loading, the final value achieved at 2,500 s was nearly equal to the equilibrium friction coefficient and denoted by μeq. Under dynamic loading, the steady-state frictional response oscillated between an upper bound and a lower bound, denoted by μub and μlb, respectively. Between tests, the glass slide was thoroughly cleaned with distilled water, alcohol and gentle scrubbing.

Figure 1.

Schematic of friction device

Experimental Protocol

Four friction tests were performed on each sample. Each sample was tested under three sinusoidal loading frequencies (1 Hz, 0.5 Hz and 0.05 Hz) and under a static load, with simultaneous sliding of the cartilage surface against glass. In the dynamic loading tests, an offset load of 4.5 N (ramped up over 10 seconds) was initially applied on the sample in order to maintain cartilage-platen contact. Cyclical compressive sinusoidal loading immediately followed this offset load, with nominal amplitude varying from 0 to 17.8 N at the desired frequency, above the initial offset load. A friction test with a static load of 13.4 N (ramped up over 20 seconds), corresponding to the mean amplitude of the dynamic loading tests (13.4 = (4.5+22.3)/2), was also performed. Between tests, the sample was equilibrated in PBS and allowed to recover for at least an hour. The ordering of the four tests on each sample was randomized.

Theoretical Analysis

The biphasic-CLE model has been shown to successfully quantify the small-strain behavior of articular cartilage under several testing configurations, including unconfined compression (Soltz and Ateshian, 2000b). A set of average material constants obtained from our previous study (Soltz and Ateshian, 2000b) was used in the current theoretical analysis (aggregate tensile and compressive moduli, H+A = 13.2 MPa and H−A = 0.64 MPa respectively; off-diagonal modulus λ2 =0.48 MPa). The permeability was set at k=2.5×10−15 m4/N.s to yield a time constant similar to the experimental response, for easier comparison. The theoretical analysis was performed for a specimen thickness of 2.1mm and diameter of 4.8mm (corresponding to the average thickness and diameter from the frictional experiments described above) under sinusoidal dynamic loading frequencies of 1 Hz, 0.5 Hz and 0.05 Hz (oscillating between 0.45 and 2.23N), and under an instantaneously applied static load of 1.34N, equivalent to the mean amplitude of the dynamic load. All analyses were carried out for 2,500 seconds. The normal load (W), axial deformation (u), fluid load (Wp) and the fluid load support (Wp/W) were calculated at each time step. W and Wp are taken to be of the same sign when both are in compression.

Once Wp / W was obtained from this theoretical analysis, the effective friction coefficient μeff was predicted using the biphasic boundary friction model (Ateshian et al., 1998). According to this model, the solid-to-solid contact force Wss is equal to the total normal load minus the portion of the normal load supported by fluid-to-fluid or fluid-to-solid interactions,

| (1) |

where φ is the fraction of the total contact area where solid-to-solid contact occurs. For idealized smooth surfaces, it is given by the product of the solid content of the opposing surfaces. In this study, where cartilage slides against impermeable glass, a value of φ=0.1 was selected, corresponding to the solid content of the superficial zone of immature bovine articular cartilage (Torzilli, 1988). The friction force F and effective friction coefficient are then given by,

| (2) |

| (3) |

where μeq is the equilibrium friction coefficient achieved when the interstitial fluid pressure subsides (Wp = 0). The value of μeq was set to the average value achieved in the experimental measurements of friction under a static load (μeq=0.153).

Statistical Analyses

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures was performed to detect differences in the experimentally measured values of μmin in all four friction tests. Similarly, ANOVA with repeated measures was used to detect differences between μeq from the static loading test and μub and μlb from the three dynamic loading tests. Statistical significance was accepted for p≤0.05, with α=0.05. Post-hoc testing of the means was performed using Bonferroni correction.

Results

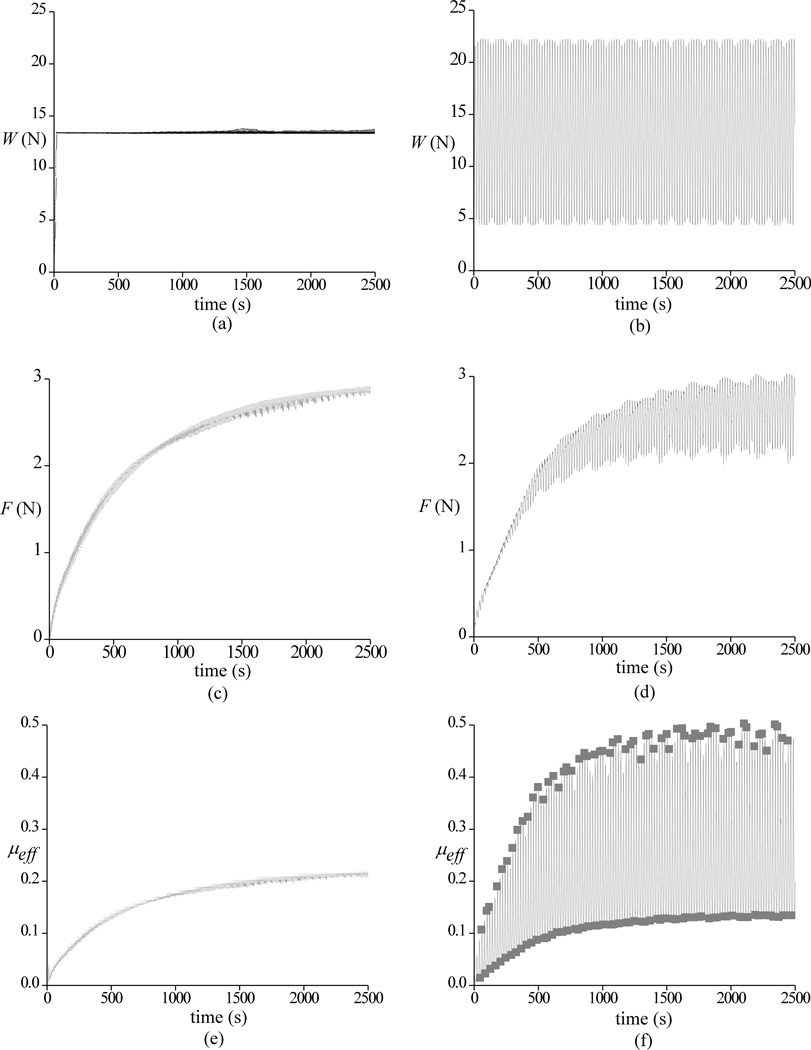

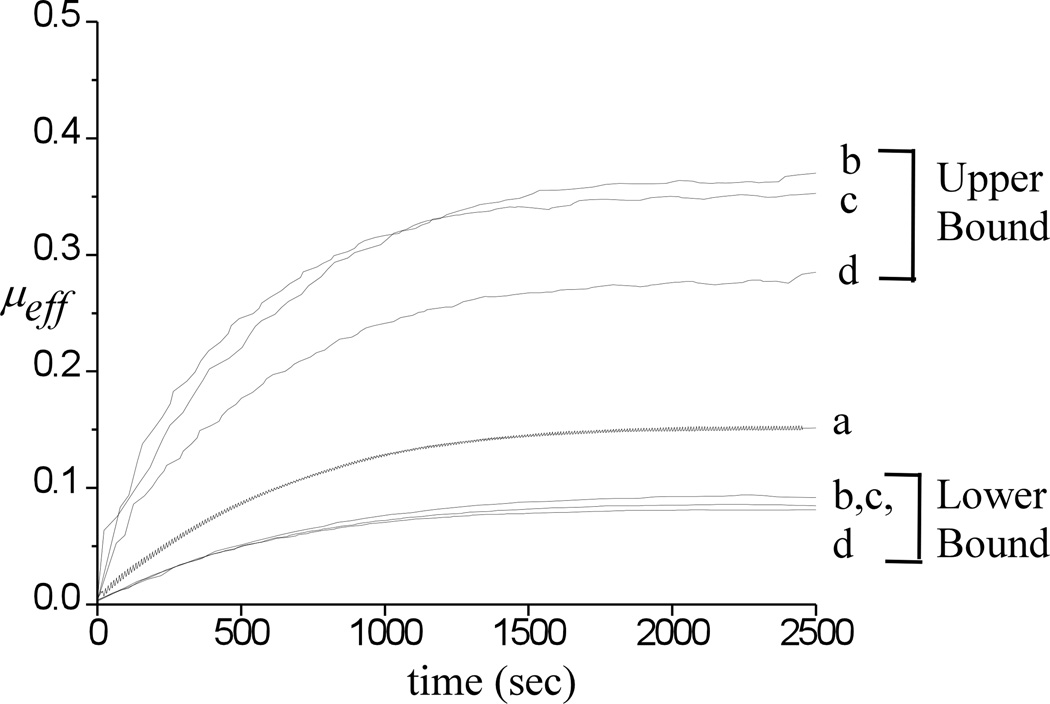

Representative experimental results for the applied load W and measured frictional force F are shown in Figure 2a–d under static loading and dynamic loading at 0.05 Hz. The friction force is observed to increase with time, both for static and dynamic loading configurations. The corresponding effective friction coefficient μeff is shown in Figure 2e,f along with a trace of the corresponding lower bound and upper bound responses under dynamic loading. For this specimen, the rise in μeff occurs at a similar rate for both static and dynamic loading. Average responses of μeff for all twelve specimens are presented in Figure 3, including the response to static loading and the lower and upper bound traces for the three dynamic loading experiments. For all three frequencies, the lower bound traces are very similar to each other and fall below the static loading response. The upper bound responses at 0.05 Hz and 0.5 Hz are also similar, but higher than the upper bound response at 1 Hz. All upper bound traces fall above the static loading response.

Figure 2.

Representative experimental results for the applied load W and measured frictional force F are shown in a,c for static loading and b,d for dynamic loading at 0.05 Hz. The corresponding effective friction coefficient μeff is shown in e,f along with a trace of the corresponding lower bound and upper bounds under dynamic loading

Figure 3.

Average responses of μeff for all twelve specimens including the response to (a) static loading and the lower and upper bound traces for (b) 0.05 Hz; (c) 0.5 Hz and (d) 1 Hz

The mean and standard deviations of μmin, μeq, μlb and μub are summarized in Table 1. Statistical analyses show that μlb at 0.05, 0.5 and 1 Hz is smaller than μeq from static loading, whereas μub at the same frequencies is higher than μub (p<0.05). No statistical differences are found among the values of μlb at all three frequencies, whereas μub at 1 Hz is smaller than at 0.5 and 0.05 Hz. Values of μmin were generally the same in all four testing configurations, with the exception that μmin at 0.5 Hz was statistically smaller than for static loading.

Table 1.

Experimental results: Minimum friction coefficient μmin from static and dynamic loading experiments. Equilibrium friction coefficient (μeq) from static loading experiment compared to lower bound (μlb) and upper bound (μub) steady-state friction coefficients from dynamic loading experiments. Within each row, identical superscripted letters indicate statistical differences among the corresponding loading configurations (p<0.05).

| Static | 0.05 Hz | 0.5 Hz | 1 Hz | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μmin | 0.005±0.003a | 0.004±0.002 | 0.003±0.001a | 0.003±0.001 |

| μeq vs μlb | 0.153±0.032a,b,c | 0.092±0.016a | 0.083±0.019b | 0.084±0.020c |

| μeq vs μub | 0.153±0.032a,b,c | 0.382±0.057a,d | 0.358±0.059b,e | 0.298±0.061c,d,e |

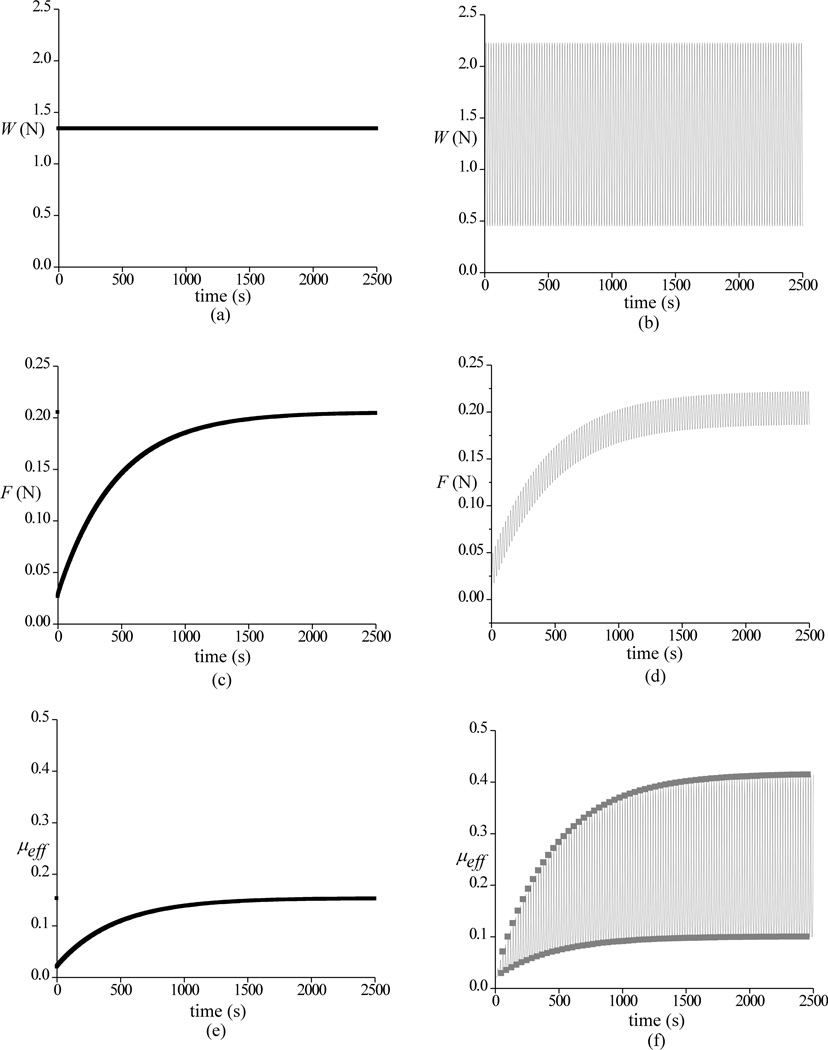

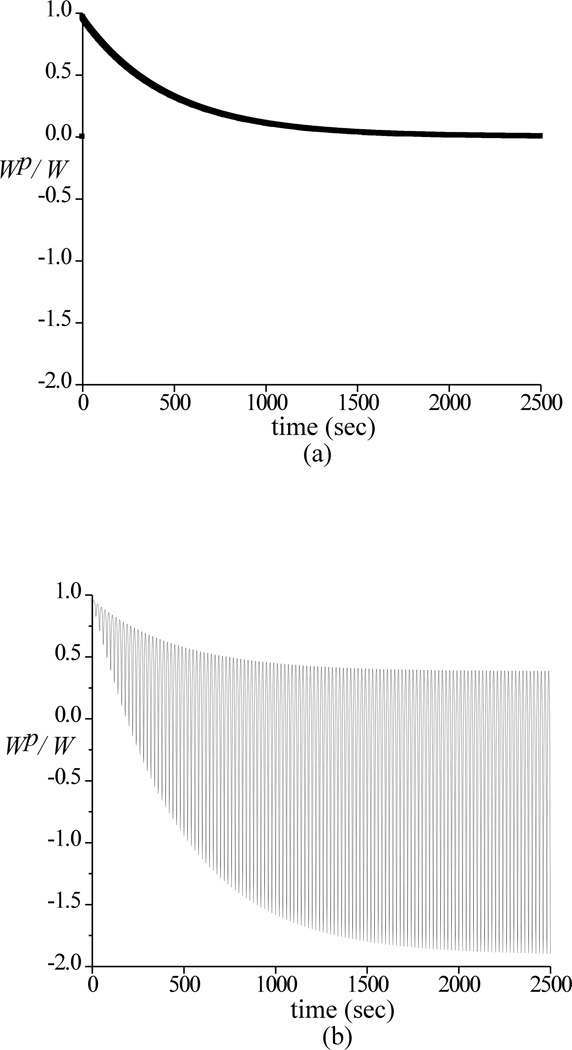

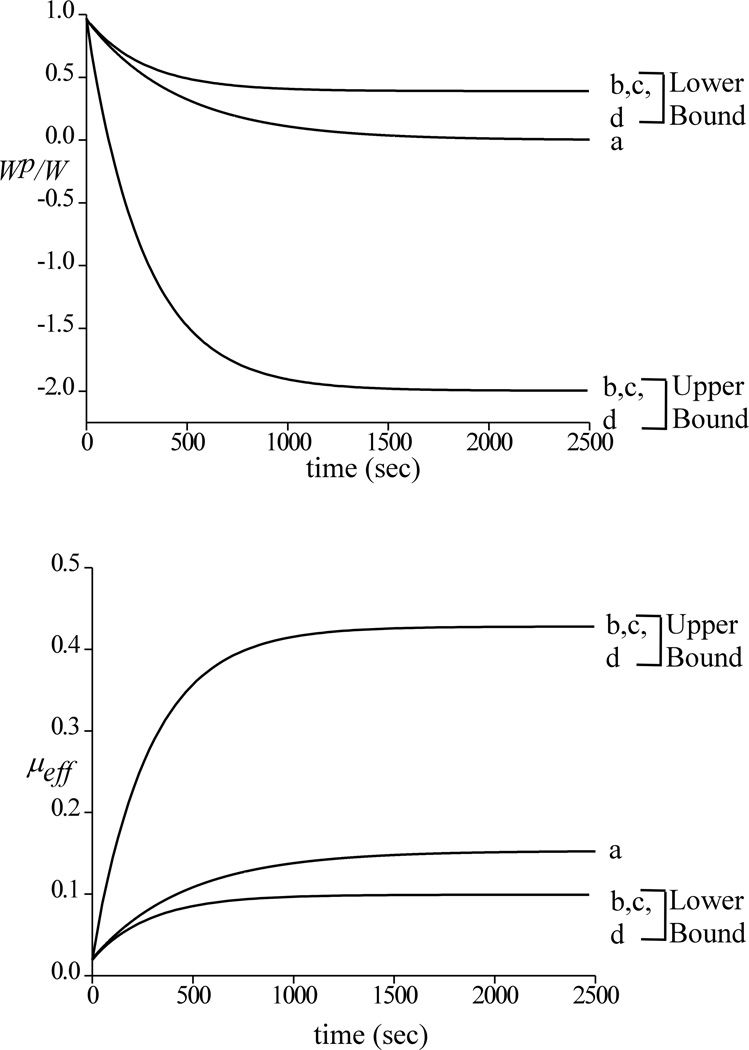

Theoretical responses for W, F and μeff are shown in Figure 4, whereas the corresponding Wp / W is presented in Figure 5 for static loading and dynamic loading at 0.05 Hz. As in the case of experimental results, a trace of the upper and lower bounds of the dynamic response is also shown. When plotting only the upper and lower bounds of the dynamic responses of Wp/W and μeff at all three frequencies (Figure 6), it is found that the envelopes of the responses are identical, spanning asymmetrically above and below the response to static loading. Corresponding theoretical predictions of μmin, μlb and μub are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 4.

Theoretical responses for the applied load W, friction force F and effective friction coefficient μeff are shown for static loading (a,c,e) and dynamic loading (b,d,f) at 0.05 Hz

Figure 5.

Theoretical responses for the interstitial fluid load support Wp/W, for static loading (a) and dynamic loading (b) at 0.05 Hz

Figure 6.

Upper and lower bounds of the dynamic responses of μeff and corresponding Wp/W for (a) static loading and dynamic loading at (b) 0.05 Hz; (c) 0.5 Hz and (d) 1 Hz

Table 2.

Theoretical predictions: Minimum friction coefficient μmin from static and dynamic loading analyses. Equilibrium friction coefficient (μeq) from static loading analysis compared to lower bound (μlb) and upper bound (μub) steady-state friction coefficients from dynamic loading analyses. Note that μeq=0.153 is prescribed a priori based on the experimental results summarized in Table 1. All other values are predicted from theory.

| Static | 0.05 Hz | 0.5 Hz | 1 Hz | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μmin | 0.020 | 0.019 | 0.019 | 0.019 |

| μeq vs μlb | 0.153 | 0.092 | 0.092 | 0.092 |

| μeq vs μub | 0.153 | 0.428 | 0.428 | 0.428 |

Discussion

Cyclical compressive loading is an important testing configuration as it is frequently encountered in our joints during activities of daily living such as walking or running. The experimental results presented in Figure 2 and Table 1 demonstrate that the friction coefficient under cyclical compressive loading oscillates above and below the response to static loading, with the upper bound steady-state friction coefficient considerably higher than the equilibrium friction coefficient, μlb > μeq. Furthermore, except for a relatively small reduction in μub at 1 Hz compared to 0.05 and 0.5 Hz, the envelope of the frictional response under dynamic loading is mostly independent of the loading frequency. These results strongly suggest that cyclical compressive loading does not provide any beneficial effect over static loading with regard to the friction coefficient. Thus the first hypothesis of this study must be rejected based on these experimental findings. Perhaps the most surprising of these experimental results, in light of physiological loading conditions, is that under steady-state cyclical compressive loading the friction coefficient can be significantly greater than under static loading.

Turning to the theoretical analysis for a possible explanation of these experimental findings, it is noted that the predicted interstitial fluid load support under cyclical compressive loading also oscillates above and below the response to static loading (Figure 5). The envelope of the response to dynamic loading is observed to be completely independent of the loading frequency (Figure 6). Furthermore, the theoretical prediction demonstrates that after a sustained period of cyclical compressive loading, the fluid pressure fluctuates above and below ambient atmospheric pressure as noted in earlier theoretical analyses (Suh, 1996), yielding negative values of Wp/W over portions of the loading cycle thus signifying that suction is occurring at the interface between the cartilage and loading platen. This suction phenomenon may be familiar to investigators who perform mechanical testing of cartilage plugs in unconfined compression with impermeable loading platens, where it may manifest itself, for example, by the cartilage plug temporarily 'sticking' to one of the loading platens upon load removal. In our recent experimental study on interstitial fluid load support in bovine articular cartilage in unconfined compression, sub-ambient interstitial fluid pressure was also measured directly with a pressure transducer upon tissue unloading (Park et al., 2003). Taking these results together, the second hypothesis of this study must also be rejected, indicating that sustained dynamic loading does not promote a more favorable interstitial fluid load support than static loading.

Substituting the theoretically predicted interstitial fluid load support into the biphasic boundary friction model of equation results in a predicted friction response (Figure 4, Table 2) which is remarkably similar to the experimental results (Figure 2, Table 1). Most significantly, it is found that the upper bound response of the friction coefficient coincides with the portions of the loading cycle when the interstitial fluid load support is negative (during suction). Thus a physical interpretation may be given to the otherwise counter-intuitive experimental finding that dynamic loading produces friction coefficients higher than static loading: During the portion of the loading cycle when the fluid load support is negative (when the applied cyclical load W is smallest in magnitude), the resulting suction produces a solid-to-solid contact force Wss which is greater in magnitude than it would otherwise be for zero or positive fluid load support (see equation (1)). Consequently, the solid-to-solid friction force F is correspondingly higher, just when W is smallest, producing a significantly higher friction coefficient than under static loading.

The results of this study raise intriguing questions about the frictional response of articular cartilage under physiological conditions. Before addressing some of these questions, it is necessary to discuss the potential limitations of the experimental and theoretical analyses described above. The load magnitudes applied in the experimental study resulted in an average contact stress of 0.74 MPa and a peak contact stress of 1.24 MPa. While such contact stresses are on the lower end of physiological loading conditions, nevertheless they resulted in axial compressive strains of ~40% in the cartilage plug under steady-state conditions. Such strain magnitudes fall in the finite deformation range. Since our biphasic-CLE model has only been formulated and experimentally validated in the range of small strains (Soltz and Ateshian, 2000b), the theoretical analysis performed in this study employed load magnitudes ten times smaller than in the experimental studies, producing peak strains of ~13% which are acceptable for small strain analyses. Despite the difference in load magnitudes between the experimental and theoretical studies, the good qualitative agreement observed between the experimental and theoretical friction coefficient suggests that the insight gained from the theoretical analysis is applicable to the experimental results. Note that, unlike the biphasic-CLE model, the friction model described in equations (1) –(3) is formulated for any range of strains.

Another potential limitation is that this study performs frictional measurements of cartilage against glass in PBS, instead of cartilage against cartilage in synovial fluid. However Forster and Fisher (Forster and Fisher, 1996) have shown that testing cartilage against cartilage yields fundamentally the same behavior as testing cartilage against a metal counterface, either in synovial fluid or Ringer's solution, with the friction coefficient rising steadily with time under a constant load. This behavior is the same as the response to a static load reported in this study (Figure 3). For example, in their subsequent friction study of cartilage against metal (Forster and Fisher, 1999), these authors reported a minimum friction coefficient of μmin = 0.006±0.005 and near-equilibrium friction coefficient of μeq = 0.498±0.088 with synovial fluid, versus μmin = 0.007±0.005 and μeq = 0.567±0.061 with Ringer's solution. These studies support our assumption that testing cartilage against glass in PBS is representative of lubrication conditions in situ, particularly with regard to its temporal response.

One of the interesting questions raised by the results of the current study is whether suction (sub-ambient interstitial fluid pressure) is likely to occur under steady-state cyclical compressive loading in situ. However, it should be noted that the ambient pressure within the sealed capsule of diarthrodial joints is typically sub-atmospheric, suggesting that suction is likely to be less significant in situ than under the laboratory testing conditions employed in this study. An important observation is that even if one were to assume in the limiting case that the interstitial fluid pressure never drops below the ambient pressure within a diarthrodial joint, the friction model of Eq.(3) would still predict an upper bound of μub = μeq when Wp/W drops to zero (ambient pressure) during a portion of the cyclical loading cycle. Thus, while suction produces more detrimental conditions, with μub > μeq, elevated friction coefficients would occur under sustained cyclical compressive loading even in the absence of sub-ambient interstitial fluid pressurization. In fact, one potential explanation for the slightly lower value of μub at 1 Hz versus 0.5 and 0.5 Hz could be that the seal between the loading platens and specimen surfaces may not have been maintained as tightly at the higher frequency; as a result, the suction effect may have been less significant at 1 Hz, bringing μub closer to μeq.

Having rejected the two hypotheses of this study, it is necessary to either accept the counter-intuitive explanation that the friction coefficient may rise to detrimental values under certain loading conditions, even in normal healthy joints, or formulate alternative hypotheses that can explain how the friction coefficient remains low under in situ conditions. Based on theoretical arguments, we adopt the latter approach: One of the key issues to keep in perspective is the time constant for the rise of the friction coefficient, when compared to the characteristic duration of loading in diarthrodial joints. In the experiments of this study, this time constant is approximately τ ~625 s, for a cyclindrical specimen of radius a=2.4 mm. According to the biphasic theory (Armstrong et al., 1984; Soltz and Ateshian, 2000b), the time constant in unconfined compression is proportional to a2/H+Ak, thus it increases with the square of the specimen radius. Contact analyses of biphasic layers (Ateshian et al., 1994; Kelkar and Ateshian, 1999) demonstrate a similar relationship between the time-constant and the contact area radius. Under in situ conditions, most diarthrodial joints produce contact areas with a radius significantly greater than the 2.8 mm radius of specimens used in the current study. Based on these theoretical considerations, a contact radius of 10 mm, for example, would result in a time constant of (10/2.8)2 × 625 ≈ 8,000 s for the rise in the friction coefficient. Therefore, one alternative hypothesis is that increasing contact areas produce longer time constants for the rise in friction, which far exceed the typical duration of loading in a joint, thus precluding elevated values in the friction coefficient.

Another alternative hypothesis is based on our earlier theoretical finding that sliding or rolling of contacting biphasic layers, which produces migrating contact areas on articular surfaces, maintains elevated interstitial fluid pressurization even under steady-state conditions. This mechanism persists as long as the sliding or rolling velocity exceeds the characteristic velocity of interstitial fluid flow (which is typically less than 1 μm/s) (Ateshian and Wang, 1995). Based on the correlation observed between high interstitial fluid load support and low friction coefficient in articular cartilage (Krishnan et al., 2004), this theoretical finding suggests that migrating contact areas on the surface of an articular layer will maintain a low friction coefficient even under steady-state conditions.

Both of these alternative hypotheses remain to be tested experimentally in our future studies. However they provide a reasonable counter-balancing alternative to the results of the current study. They may also explain the difference between the current results and the studies of Malcom (Malcom, 1976) who found that cyclical compressive loading between two articular layers does maintain a low friction coefficient under steady-state conditions.

It is interesting that despite the rejection of the hypothesis that cyclical compressive loading promotes more elevated interstitial fluid pressurization under steady-state conditions than static loading, the good agreement observed between theory and experiments in the current study strengthens the hypothesis that interstitial fluid pressurization is the primary regulator of the frictional response of articular cartilage. Indeed, it is because of the oscillating interstitial fluid load support that the friction coefficient under cyclical compressive loading can achieve values above and below the response to static loading. In our opinion, no other existing hypothesis for cartilage lubrication can explain how cyclical loading of cartilage can produce an upper bound on the friction coefficient that exceeds the friction coefficient under static loading.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funds from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (AR43628).

References

- Armstrong CG, Lai WM, Mow VC. An analysis of the unconfined compression of articular cartilage. J Biomech Eng. 1984;106:165–173. doi: 10.1115/1.3138475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ateshian GA, Lai WM, Zhu WB, Mow VC. An asymptotic solution for the contact of two biphasic cartilage layers. J Biomech. 1994;27:1347–1360. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ateshian GA, Wang H. A theoretical solution for the frictionless rolling contact of cylindrical biphasic articular cartilage layers. J Biomech. 1995;28:1341–1355. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ateshian GA, Wang H, Lai WM. The role of interstitial fluid pressurization and surface porosities on the boundary friction of articular cartilage. J Tribology. 1998;120:241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett CH, Cobbold AF. Lubrication within living joints. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1962;44:662. [Google Scholar]

- Charnley J. Symposium on Biomechanics. London: Inst of Mech Engrs; 1959. The lubrication of animal joints; pp. 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Charnley J. The lubrication of animal joints in relation to surgical reconstruction by arthroplasty. Ann Rheum Dis. 1960;19:10–19. doi: 10.1136/ard.19.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curnier A, He QC, Zysset P. Conewise linear elastic materials. J Elasticity. 1995;37:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman CJ. Exercise and Sports Sciences Review. In: Wilmore JH, editor. Kinematic analysis of running. Vol. 3. New York: Academic Press; 1975. pp. 193–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster H, Fisher J. The influence of loading time and lubricant on the friction of articular cartilage. Proc Inst Mech Eng [H] 1996;210:109–119. doi: 10.1243/PIME_PROC_1996_210_399_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster H, Fisher J. The influence of continuous sliding and subsequent surface wear on the friction of articular cartilage. Proc Inst Mech Eng [H] 1999;213:329–345. doi: 10.1243/0954411991535167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones ES. Joint lubrication. Lancet. 1934;228:1426–1427. [Google Scholar]

- Jones ES. Joint lubrication. Lancet. 1936;230:1043–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Kelkar R, Ateshian GA. Contact creep of biphasic cartilage layers. Journal of Applied Mechanics, Transactions ASME. 1999;66:137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan R, Park S, Eckstein F, Ateshian GA. Inhomogeneous cartilage properties enhance superficial interstitial fluid support and frictional properties, but do not provide a homogeneous state of stress. J Biomech Eng. 2003;125:569–577. doi: 10.1115/1.1610018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan R, Kopacz M, Ateshian GA. Experimental verification of the role of interstitial fluid pressurization in cartilage lubrication. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:565–570. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn FC. Lubrication of animal joints. I. The arthrotripsometer. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1967;49:1079–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn FC, Radin EL. Lubrication of animal joints. 3. The effect of certain chemical alterations of the cartilage and lubricant. Arthritis Rheum. 1968;11:674–682. doi: 10.1002/art.1780110510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macirowski T, Tepic S, Mann RW. Cartilage stresses in the human hip joint. J Biomech Eng. 1994;116:10–18. doi: 10.1115/1.2895693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcom LL. Ph.D. thesis. San Diego: University of California; 1976. An experimental investigation of the frictional and deformational response of articular cartilage interfaces to static and dynamic loading. [Google Scholar]

- McCutchen CW. Sponge-hydrostatic and weeping bearings. Nature. 1959;184:1284. doi: 10.1038/1841284a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutchen CW. The frictional properties of animal joints. Wear. 1962;5:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Mow VC, Kuei SC, Lai WM, Armstrong CG. Biphasic creep and stress relaxation of articular cartilage in compression? Theory and experiments. J Biomech Eng. 1980;102:73–84. doi: 10.1115/1.3138202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oloyede A, Broom ND. Is classical consolidation theory applicable to articular cartilage deformation? Clin Biomech. 1991;6:206–212. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(91)90048-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Krishnan R, Nicoll SB, Ateshian GA. Cartilage interstitial fluid load support in unconfined compression. J Biomech. 2003;36:1785–1796. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00231-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul JP, McGrouther DA. Forces transmitted at the hip and knee joint of normal and disabled persons during a range of activities. Acta Orthop Belg. 1975;41(Suppl 1):78–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltz MA, Ateshian GA. Experimental verification and theoretical prediction of cartilage interstitial fluid pressurization at an impermeable contact interface in confined compression. J Biomech. 1998;31:927–934. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltz MA, Ateshian GA. Interstitial fluid pressurization during confined compression cyclical loading of articular cartilage. Ann Biomed Eng. 2000a;28:150–159. doi: 10.1114/1.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltz MA, Ateshian GA. A Conewise Linear Elasticity mixture model for the analysis of tension-compression nonlinearity in articular cartilage. J Biomech Eng. 2000b;122:576–586. doi: 10.1115/1.1324669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh JK. Dynamic unconfined compression of articular cartilage under a cyclic compressive load. Biorheology. 1996;33:289–304. doi: 10.1016/0006-355x(96)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torzilli PA. Water content and equilibrium water partition in immature cartilage. J Orthop Res. 1988;6:766–769. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100060520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth A, Dowson D, Wright V. Some new evidence on human joint lubrication. Ann Rheum Dis. 1975;34:277–285. doi: 10.1136/ard.34.4.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]