Abstract

Background

Despite the high prevalence of clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) among older men, there remains a notable absence of studies focused on BPH prevention.

Objective

To determine if finasteride prevents incident clinical BPH in healthy older men.

Design, setting, and participants

Data for this study are from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. After excluding those with a history of BPH diagnosis or treatment, or an International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) ≥8 at study entry, 9253 men were available for analysis.

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis

The primary outcome was incident clinical BPH, defined as the initiation of medical treatment, surgery, or sustained, clinically significant urinary symptoms (IPSS >14). Finasteride efficacy was estimated using Cox proportional regression models to generate hazards ratios (HRs).

Results and limitations

Mean length of follow-up was 5.3 yr. The rate of clinical BPH was 19 per 1000 person-years in the placebo arm and 11 per 1000 person-years in the finasteride arm (p < 0.001). In a covariate-adjusted model, finasteride reduced the risk of incident clinical BPH by 40% (HR: 0.60; 95% confidence interval, 0.51–0.69; p < 0.001). The effect of finasteride on incident clinical BPH was attenuated in men with a body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 (pinteraction = 0.04) but otherwise did not differ significantly by physical activity, age, race, current diabetes, or current smoking. The post hoc nature of the analysis is a potential study limitation.

Conclusions

Finasteride substantially reduces the risk of incident clinical BPH in healthy older men. These results should be considered in formulating recommendations for the use of finasteride to prevent prostate diseases in asymptomatic older men.

Keywords: Prostatic hyperplasia, Finasteride, 5α-reductase inhibitor, Prevention and control, Prostatic neoplasm

1. Introduction

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a chronic disease that affects as many as 75% of men by age 70 yr, and in the United States, it results in more than $4 billion in treatment costs annually [1–4]. Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), the most common clinical manifestation of BPH, are independently associated with increased risks of mortality, falls, diminished quality of life, depression, and impaired activities of daily living [5–8].

Despite the high prevalence of BPH among older men, there remains a conspicuous absence of studies focused on BPH prevention. Several lines of evidence support the consideration of finasteride, a 5α-reductase inhibitor (5-ARI) that blocks the conversion of the sex steroid hormone testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), for the primary prevention of BPH. First, DHT is a potent androgen that promotes prostate growth and is an essential component of BPH pathogenesis [9]. Second, finasteride significantly decreases serum and intraprostatic DHT concentrations, reduces prostate volume, and is approved for the treatment of clinical BPH [10,11]. Third, studies of asymptomatic older men have reported strong direct associations of serum DHT and DHT metabolite concentrations with BPH risk, suggesting that DHT suppression might delay or prevent clinical BPH onset [12,13]. Finally, clinical trials of prostate cancer prevention and clinical BPH have demonstrated that finasteride decreases the risks of severe BPH sequelae, including acute urinary retention, urinary infection, and noncancer prostate surgery [10,14,15].

The efficacy of finasteride for the primary prevention of clinical BPH has not been investigated. It is not known whether finasteride prevents or delays LUTS onset or other adverse events among men with no or mild symptoms [10,14,15].

We report results from a secondary analysis of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT). The PCPT, which collected extensive data on LUTS and medical and surgical treatments for BPH, constitutes a robust and unique resource for the evaluation of the efficacy of finasteride for the primary prevention of symptomatic BPH.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population

Data are from the PCPT, a randomized placebo-controlled trial testing whether finasteride reduces prostate cancer risk [14]. Extensive demographic and medical data, including diagnosis of and treatment for BPH, were collected at the baseline, 6-mo, and annual clinic visits and at every 3- and 9-mo phone contact between clinic visits. Baseline body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (in kilograms) divided by height (meters squared) and categorized as normal (BMI <25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2). Baseline physical activity was categorized into four levels: sedentary, light, moderate, and very active [16].

2.2. Assessment of benign prostatic hyperplasia symptoms and definition of incident benign prostatic hyperplasia

At the recruitment, baseline, and annual clinic visits, participants completed the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS). We excluded participants who at baseline reported BPH medical treatment, BPH surgery, or IPSS ≥8. We defined incident clinical BPH as the first event of report of medical treatment, surgery, or sustained, clinically significant BPH symptoms. Medical treatment included uroselective α-blockers (tamsulosin) and 5-ARIs (finasteride). We defined a report of nonspecific α-blocker therapy (doxazosin, prazosin, or terazosin) as BPH if there was concomitant evidence of BPH by either self-report or by symptoms (one report of an IPSS >14 or any two reports of an IPSS ≥12 at any time prior to the report of medication use). Surgical treatments included transurethral prostatectomy, open prostatectomy, urethral balloon dilation, and laser prostatectomy. We defined the onset of clinically significant BPH symptoms as the second report of an IPSS >14 [17,18].

2.3. Statistical analysis

We based all analyses on the time between randomization and either BPH incidence or censoring event. For cases defined by treatment (medical or surgical), we defined incidence time as the date of treatment. If treatment date was not reported, we defined incidence time as the midpoint between the prior quarterly visit and the visit when BPH treatment was reported. For cases defined by IPSS, we defined incidence time as the midpoint between the second elevated IPSS and preceding IPSS (most often the previous year) to account for the fact that onset of clinical BPH likely occurred at a point during the time interval between assessments rather than on the exact date of completion of the second IPSS questionnaire. We censored noncases at the first event of (1) medical treatment with a nonspecific BPH drug outside of the study without evidence of BPH, (2) prostate cancer diagnosis, or (3) the last recorded IPSS (which included patients who had died).

We calculated incidence rates as the annual incidence per 1000 person-years of observation. We used chi-square tests to determine whether the baseline distribution of covariates differed between finasteride and placebo arms. We used Cox proportional hazards models to compare unadjusted and covariate-adjusted hazards ratios (HRs) between finasteride and placebo arms. All models were adjusted for age, race, BMI, physical activity, current smoking status, and diabetes; controlling for additional factors associated with BPH, including family history of prostate cancer, baseline IPSS, and baseline prostate-specific antigen (PSA), did not affect results.

Additional models tested whether the effect of finasteride differed by age, race, BMI, diabetes, physical activity, and smoking status by adding an interaction term to the proportional hazards model. Interaction tests were based on p values for the interaction of treatment and a categorical variable for age, BMI, and physical activity or a dummy variable for race, diabetes, and smoking status.

We calculated the number of men needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one additional BPH case as the inverse of the difference in survivorship at time t between finasteride and placebo arms for a specified population, using the full model to determine parameter estimates. We calculated the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the NNT using the standard errors from the survival distribution. All analyses used SAS v.9.2 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Study population

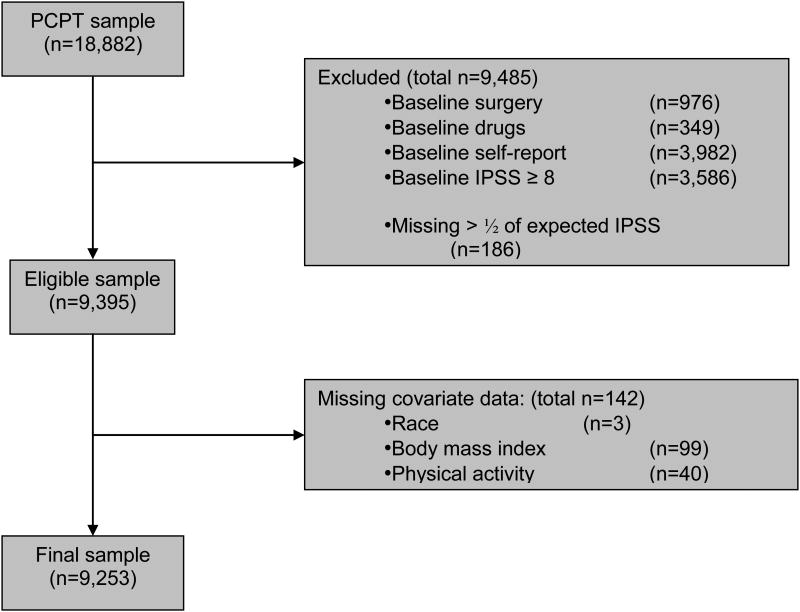

Of the 18 882 men enrolled in the PCPT, 9253 (49%) reported a baseline IPSS <8, did not have a history of physician-diagnosed or treated BPH, were not taking BPH medications at baseline, had completed at least 50% of annual IPSS assessments, and were not missing baseline covariate data (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Composition of analytic cohort: the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT). IPSS = International Prostate Symptom Score.

3.2. Demographic, health, and lifestyle characteristics at baseline

Distributions of age, race, BMI, diabetes prevalence, smoking, and physical activity were similar in the finasteride and placebo arms (Table 1). Participants were mostly white, overweight or obese, and nonsmokers. Mean age was 62.3 yr (standard deviation [SD]: 5.4) and mean BMI was 27.8 kg/m2 (SD: 4.1).

Table 1. Incidence of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia by demographic and health-related characteristics and stratified by treatment arm in the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial.

| Placebo (n = 4691) | Finasteride (n = 4562) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Range | n | % | Events | Person-years | Rate | Mean (SD) | Range | n | % | Events | Person-years | Rate | p value* | |

| Age, yr | 62.4 (5.4) | 54–85 | 62.3 (5.4) | 54–83 | 0.17 | ||||||||||

| 54–59 | 1686 | 36 | 111 | 9352 | 11.9 | 1691 | 37 | 73 | 8809 | 8.3 | |||||

| 60–64 | 1484 | 32 | 150 | 7978 | 18.8 | 1480 | 32 | 82 | 7504 | 10.9 | |||||

| 65+ | 1521 | 32 | 208 | 7907 | 26.3 | 1391 | 30 | 108 | 7238 | 14.9 | |||||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||||||||

| White | 4336 | 92 | 425 | 23 537 | 18.1 | 4218 | 92 | 240 | 21 847 | 11.0 | 0.96 | ||||

| African American | 172 | 4 | 20 | 817 | 24.5 | 163 | 4 | 13 | 790 | 16.5 | |||||

| Hispanic | 112 | 2 | 13 | 565 | 23.0 | 115 | 3 | 8 | 581 | 13.8 | |||||

| Other | 71 | 2 | 11 | 318 | 34.6 | 66 | 1 | 2 | 332 | 6.0 | |||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.7 (4.1) | 16.5–54.4 | 27.8 (4.1) | 16.6–57.9 | 0.69 | ||||||||||

| <25 | 1162 | 25 | 115 | 6330 | 19.4 | 1121 | 25 | 59 | 5912 | 10.0 | |||||

| 25–29 | 2454 | 52 | 249 | 13 174 | 18.9 | 2324 | 51 | 122 | 11971 | 10.2 | |||||

| 30+ | 1075 | 23 | 105 | 5703 | 18.4 | 1117 | 24 | 82 | 5667 | 14.5 | |||||

| Diabetes | 0.42 | ||||||||||||||

| No | 4252 | 91 | 427 | 22 719 | 18.8 | 4153 | 91 | 230 | 21 224 | 10.8 | |||||

| Yes | 439 | 9 | 42 | 2518 | 16.7 | 409 | 9 | 33 | 2326 | 14.2 | |||||

| Physical activity | 0.38 | ||||||||||||||

| Sedentary | 764 | 16 | 77 | 4034 | 19.1 | 809 | 18 | 57 | 4129 | 13.8 | |||||

| Light | 2013 | 43 | 195 | 10 799 | 18.1 | 1810 | 40 | 102 | 9205 | 11.1 | |||||

| Moderate | 1447 | 31 | 143 | 7904 | 18.1 | 1430 | 31 | 78 | 7001 | 10.3 | |||||

| High | 467 | 10 | 54 | 2500 | 21.6 | 513 | 11 | 26 | 2424 | 9.9 | |||||

| Current smoker | 0.97 | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 397 | 8 | 40 | 2038 | 19.6 | 385 | 8 | 29 | 1884 | 15.4 | |||||

| No | 4294 | 92 | 429 | 23 199 | 18.5 | 4177 | 92 | 234 | 21 666 | 10.8 | |||||

| Family history of prostate cancer | 0.17 | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 705 | 15 | 63 | 3902 | 16.1 | 733 | 16 | 42 | 3940 | 10.7 | |||||

| No | 3986 | 85 | 406 | 21 335 | 19.0 | 3829 | 84 | 221 | 19610 | 11.3 | |||||

| Baseline PSA | 1.2 (0.7) | 0.3–4 | 1.2 (0.7) | 0.3–4 | 0.33 | ||||||||||

| <1.0 ng/ml | 2219 | 47 | 188 | 12 152 | 15.5 | 2135 | 47 | 118 | 10 986 | 10.7 | ng/mL | ||||

| 1.0–2.0 ng/ml | 1764 | 38 | 182 | 9402 | 19.4 | 1712 | 38 | 97 | 9042 | 10.7 | |||||

| >2.0 ng/ml | 708 | 15 | 99 | 3682 | 26.9 | 715 | 16 | 48 | 3522 | 13.6 | ng/mL | ||||

| Baseline IPSS | 3.8 (2) | 0–7.5 | 2366 | 50 | 120 | 13 100 | 9.2 | 3.8 (2) | 0–7.5 | 2305 | 51 | 59 | 12 201 | 4.8 | 0.50 |

| 0.0–3.9 | 1343 | 29 | 157 | 7233 | 21.7 | 1318 | 29 | 89 | 6688 | 13.3 | |||||

| 4.0–5.9 | 982 | 21 | 192 | 4904 | 39.2 | 939 | 21 | 115 | 4660 | 24.7 | |||||

| 6.0–7.0 | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 4691 | 100 | 469 | 25 237 | 18.6 | 4562 | 100 | 263 | 23 550 | 11.2 | |||||

SD = standard deviation; BMI = body mass index; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; IPSS = International Prostate Symptom Score.

The p values were calculated using t tests for continuous variables (age, BMI, baseline IPSS), chi-square tests for nominal categorical variables (race, current smoking status, and family history of prostate cancer), and Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests for ordered categorical variables (age, BMI, diabetes, physical activity, baseline IPSS) and compare the mean (continuous variables) or distribution of covariates between finasteride and placebo arm.

3.3. Cumulative incidence and hazards ratios

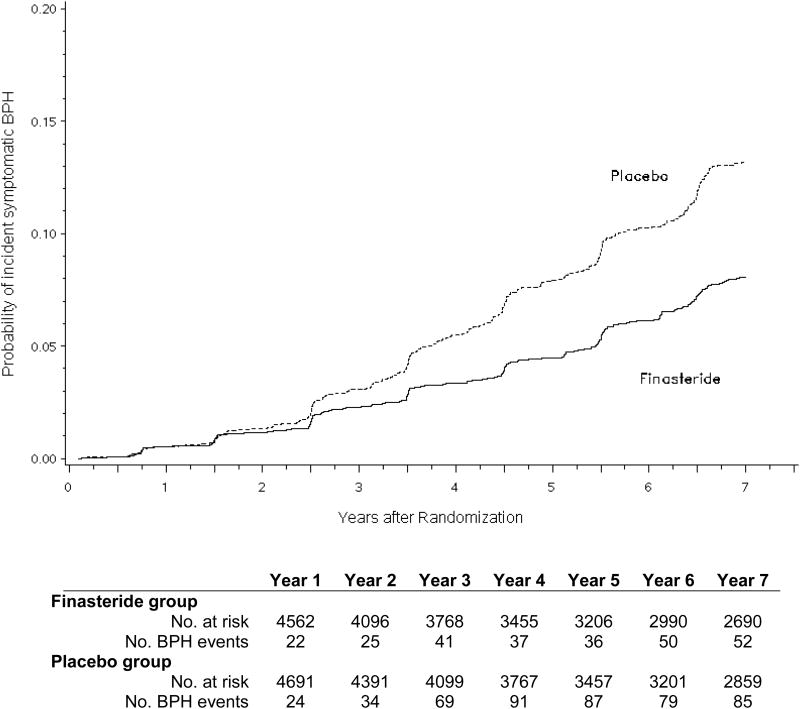

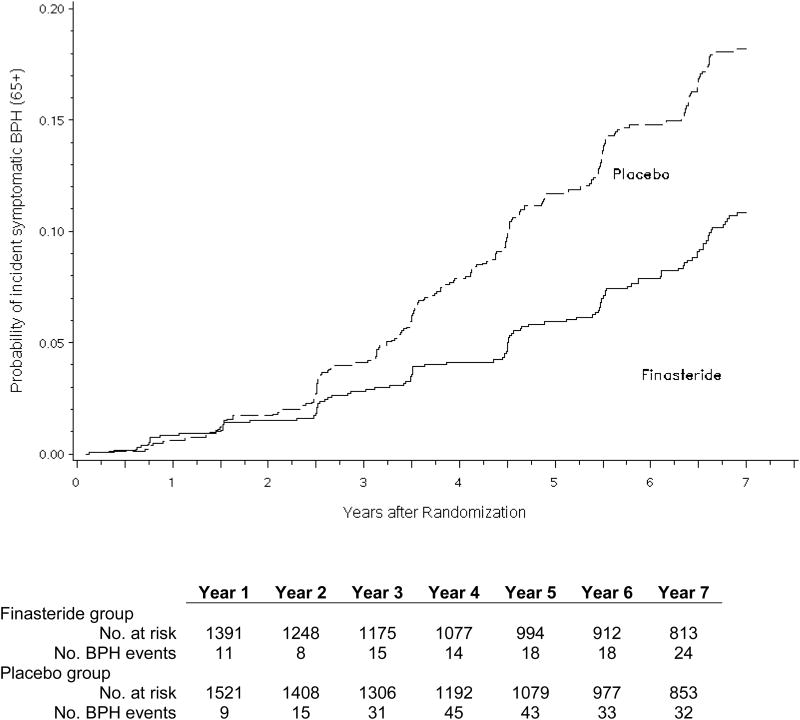

There were a total of 469 events of incident clinical BPH among 25 237 person-years of follow-up (18.6 per 1000 person-years) in the placebo arm and 263 events among 23 550 person-years of follow-up (11.2 per 1000 person-years) in the finasteride arm (Fig. 2a). In both unadjusted and adjusted proportional hazards models, finasteride decreased the risk of incident clinical BPH by 40% (Table 2). Among men ≥65 yr of age, there were a total of 208 events of incident clinical BPH among 7907 person-years of follow-up (26.3 per 1000 person-years) in the placebo arm and 108 events among 7238 person-years of follow-up (14.9 per 1000 person-years) in the finasteride arm (Fig. 2b). In these older men, finasteride decreased the risk of incident clinical BPH by 44% (HR: 0.56; 95% CI, 0.44–0.70; p < 0.001) after multivariable adjustment.

Fig. 2.

(a) Unadjusted cumulative incidence of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) comparing finasteride with placebo for the entire analytic cohort (n = 9253); (b) unadjusted cumulative incidence of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia in finasteride and placebo arms among men ≥65 yr at baseline (n = 2912).

Table 2. Model of the association of finasteride with benign prostatic hyperplasia, unadjusted and adjusted for covariates.

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Intent-to-treat analysis | |||

| Unadjusted | 0.60 | 0.52–0.70 | <0.0001 |

| Multivariate adjusted* | 0.60 | 0.51–0.69 | <0.0001 |

| Noncompliant men censored | |||

| Unadjusted | 0.57 | 0.49–0.67 | <0.0001 |

| Multivariate adjusted a | 0.57 | 0.48–0.66 | <0.0001 |

CI = confidence interval.

Adjusted for race, body mass index, diabetes, physical activity, and current smoking status.

In additional analyses censoring men who went off treatment, the protective effect of finasteride on clinical BPH risk was numerically larger, decreasing the risk of incident symptomatic BPH by 43% in unadjusted and multivariate adjusted models, respectively (Table 2). The inclusion of men with a baseline IPSS between 8 and 12 only slightly reduced the efficacy of finasteride (HRadj: 0.67; 95% CI, 0.60–0.74; p < 0.0001).

3.4. Subgroup analyses

Analyses of finasteride and clinical BPH risk among strata defined by age, race/ethnicity, BMI, diabetes, physical activity, and smoking status demonstrated that the effect of finasteride on incident BPH was attenuated in obese men (HRadj: 0.79; 95% CI, 0.59–1.06, pinteraction = 0.04). The effects of finasteride on incident clinical BPH did not significantly differ by age, race, diabetes, physical activity, or current smoking (Table 3). An additional analysis showed no significant associations of baseline PSA with risk of incident clinical BPH (area under the curve = 0.5) or finasteride effect (pinteraction = 0.06).

Table 3. Effects of finasteride treatment within strata defined by age, race, body mass index, diabetes, physical activity, and current smoking status.

|

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Finasteride | ||

|

| ||

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | |

| Age, yr | ||

| 54–59 | 0.68 | 0.51–0.92 |

| 60–64 | 0.58 | 0.44–0.75 |

| 65+ | 0.56 | 0.45–0.71 |

| pinteraction = 0.34a | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 0.60 | 0.52–0.71 |

| African American | 0.65 | 0.32–1.30 |

| Hispanic | 0.58 | 0.24–1.40 |

| Other | 0.21 | 0.05–0.93 |

| pinteraction = 0.58b | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||

| <25 | 0.51 | 0.37–0.70 |

| 25–29 | 0.55 | 0.44–0.69 |

| ≥30 | 0.79 | 0.59–1.06 |

| pinteraction =0.04a | ||

| Diabetes | ||

| No | 0.57 | 0.49–0.67 |

| Yes | 0.82 | 0.52–1.29 |

| pinteraction = 0.16b | ||

| Physical activity | ||

| Sedentary | 0.75 | 0.53–1.05 |

| Light | 0.60 | 0.47–0.76 |

| Moderate | 0.55 | 0.42–0.73 |

| High | 0.47 | 0.30–0.75 |

| pinteraction = 0.09a | ||

| Current smoker | ||

| No | 0.58 | 0.49–0.68 |

| Yes | 0.77 | 0.48–1.25 |

| pinteraction = 0.26b | ||

CI = confidence interval.

The p interaction values derived from interaction of treatment and ordered variable for age, body mass index, physical activity, and baseline International Prostate Symptom Score.

The p interaction values derived from interaction of treatment and categorical variable for race, diabetes, and smoking status.

3.5. Number needed to treat

The NNT to prevent one case of clinical BPH over 7 yr was 58 (95% CI, 35–177) for men 55–59 yr of age, 42 (95% CI, 25–123) for men 60–64 yr, and 31 (95% CI, 19–83) for men ≥65 yr. In addition, for men ≥65 yr, the 5- and 6-yr NNT values were 54 (95% CI, 32–152) and 40 (95% CI, 25–111), respectively.

4. Discussion

This study is the first experimental analysis to investigate the primary prevention of clinical BPH. Based on a large randomized double-blind clinical trial, the daily use of 5 mg of finasteride reduced the incidence of clinical BPH by 40%. Among men ≥65 yr of age, finasteride decreased the risk by 44%. The effect of finasteride on incident clinical BPH did not differ significantly by age, race, diabetes, physical activity, or current smoking. Based on 7 yr of treatment, the NNT to prevent one clinical BPH case ranged from 58 for men 55–59 yr of age to 31 for men ≥65 yr.

These data provide the first clinical evidence that BPH may be prevented and directly inform the ongoing scientific and health policy dialogue with respect to the use of 5-ARIs for the chemoprevention of prostate cancer [19,20]. Two large randomized clinical trials and a systematic review demonstrated a decreased risk of incident prostate cancer with the use of prophylactic 5-ARI therapy [14,15,21]. Although not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the prevention of prostate cancer (www.drugs.com/pro/finasteride), the American Urological Association (AUA) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology have recommended that some asymptomatic men may benefit from a conversation about the benefits and risks of finasteride for prostate cancer prevention [22]. Based on our findings, finasteride could be considered as a single prophylactic agent for two of the most common and costly diseases of elderly men: BPH and prostate cancer. Such a consideration must be weighed against the potential risks of finasteride treatment including sexual dysfunction, gynecomastia, and a modestly increased incidence of diagnosis of high-grade prostate cancer (for which the FDA has issued an advisory) [14,21,22]. Nevertheless, in light of these data, future scientific, clinical, and health policy deliberations of finasteride prophylaxis should incorporate decreased incidence of clinical BPH as a potential benefit.

Within this context, it is worth noting that the 7-yr NNT values of finasteride for clinical BPH prevention are comparable with published NNT values for aspirin, statins, diuretics, and β-blockers for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease [23–25]. Because our definition of symptomatic BPH was more conservative than published clinical guidelines, it is possible that our analyses underestimated the magnitude of the risk reductions, overestimated the NNT values, and thus underestimated the potential population benefits of finasteride prophylaxis. It is also reasonable to postulate that combining primary prevention of clinical BPH and prostate cancer into a single outcome (ie, incidence of any prostate disease) would further decrease the NNT values and present a more favorable cost-benefit profile. However, although BPH prevention is an important public health endeavor, its overall morbidity is less than that of myocardial infarction or stroke, and further studies of cost effectiveness are needed with respect to finasteride-mediated prevention of LUTS, BPH medication use, and BPH surgery.

We also observed an apparent diminished efficacy of finasteride for clinical BPH prevention among obese men. This finding is novel and suggests that obesity potentially attenuates the effect of 5-ARIs on BPH. A preponderance of—but not all—published studies supports a positive association of obesity with prevalent and incident BPH as measured by multiple different clinical end points [17,26]. It is possible that the potential mechanisms by which obesity increases the risk of BPH, including inflammatory pathways and alterations in endogenous sex steroid hormone levels, may counteract the beneficial outcomes of finasteride [27]. For example, obesity increases serum estrogen concentrations through peripheral aromatization of serum testosterone, and changes in intraprostatic estrogen might promote prostate growth independently of the DHT pathways through which finasteride exerts its clinical effects [9]. Further identification of men with differential responses to finasteride prophylaxis would potentially increase the utility of using finasteride for clinical BPH prevention by identifying particular groups of men most likely to benefit.

Notable strengths of this study include its use of data from a large randomized clinical trial, a conservative definition of BPH requiring multiple reports of clinically significant LUTS, and a focus on participants who were free of clinically significant BPH symptoms at baseline. One limitation of this study was the post hoc nature of the analysis. Another limitation is the generalizability of the results because the PCPT enrolled relatively healthy, predominantly white men, which potentially diminishes the external validity of the findings. Still, a healthy study population also may strengthen the applicability of the findings to the general population because most community-dwelling older men are relatively healthy compared with less independent age-matched peers. In these analyses the finasteride effect was independent of age and race. Finally, because there are no consensus recommendations for defining BPH in clinical research, and urinary symptoms may be nonspecific, misclassification of cases may have occurred. Yet misclassification events would likely have been nondifferential with respect to the finasteride and placebo arms and therefore not have biased the results. We also minimized the likelihood of misclassification by using a definition of clinical BPH that was more conservative that those used in prior clinical trials [10], most observational studies [3], and evidence-based practice guidelines such as the AUA [28]. The conservative character of our definition, in fact, might have underestimated the true number of cases in both arms and led to a cumulative incidence less than what might be encountered in clinical practice.

5. Conclusions

In this analysis of data from the PCPT, finasteride substantially reduced the incidence of clinical BPH. These findings should be considered in formulating recommendations for using finasteride to prevent clinical BPH and prostate cancer in older men.

Take-home message.

Finasteride reduces the risk of incident symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia by 40% in healthy asymptomatic older men. These data should be considered in formulating recommendations for the use of finasteride to prevent prostate diseases in asymptomatic older men.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: Urologic Diseases in America Project.

Footnotes

Author contributions: J. Kellogg Parsons had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Parsons, Schenck, Kristal, Thompson.

Acquisition of data: Schenck, Kristal.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Parsons, Schenck, Kristal, Arnold, Messer, Till.

Drafting of the manuscript: Parsons, Schenck, Kristal.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Parsons, Schenck, Kristal, Thompson.

Statistical analysis: Schenck, Kristal, Arnold, Messer, Till.

Obtaining funding: Parsons.

Administrative, technical, or material support: None.

Supervision: None.

Other (specify): None.

Financial disclosures: I certify that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/ affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Saigal CS, Joyce G. Economic costs of benign prostatic hyperplasia in the private sector. J Urol. 2005;173:1309–13. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000152318.79184.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei JT, Calhoun E, Jacobsen SJ. Urologic Diseases in America Project: benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2005;173:1256–61. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000155709.37840.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kupelian V, Wei JT, O'Leary MP, et al. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms and effect on quality of life in a racially and ethnically diverse random sample: the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2381–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parsons JK, Bergstrom J, Silberstein J, Barrett-Connor E. Prevalence and characteristics of lower urinary tract symptoms in men aged > or = 80 years. Urology. 2008;72:318–21. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engstrom G, Henningsohn L, Steineck G, Leppert J. Self-assessed health, sadness and happiness in relation to the total burden of symptoms from the lower urinary tract. BJU Int. 2005;95:810–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor BC, Wilt TJ, Fink HA, et al. Prevalence, severity, and health correlates of lower urinary tract symptoms among older men: the MrOS study. Urology. 2006;68:804–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parsons JK, Mougey J, Lambert L, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms increase the risk of falls in older men. BJU Int. 2009;104:63–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kupelian V, Fitzgerald MP, Kaplan SA, Norgaard JP, Chiu GR, Rosen RC. Association of nocturia and mortality: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Urol. 2011;185:571–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andriole G, Bruchovsky N, Chung LW, et al. Dihydrotestosterone and the prostate: the scientific rationale for 5alpha-reductase inhibitors in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2004;172:1399–403. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000139539.94828.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McConnell JD, Roehrborn CG, Bautista OM, et al. The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2387–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amory JK, Wang C, Swerdloff RS, et al. The effect of 5alpha-reductase inhibition with dutasteride and finasteride on semen parameters and serum hormones in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1659–65. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kristal AR, Schenk JM, Song Y, et al. Serum steroid and sex hormone-binding globulin concentrations and the risk of incident benign prostatic hyperplasia: results from the prostate cancer prevention trial. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:1416–24. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parsons JK, Palazzi-Churas K, Bergstrom J, Barrett-Connor E. Prospective study of serum dihydrotestosterone and subsequent risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia in community dwelling men: the Rancho Bernardo Study. J Urol. 2010;184:1040–4. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson IM, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. The influence of finasteride on the development of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:215–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andriole GL, Bostwick DG, Brawley OW, et al. Effect of dutasteride on the risk of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1192–202. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kristal AR, Chi C, Tangen CM, Goodman PJ, Etzioni R, Thompson IM. Associations of demographic and lifestyle characteristics with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) concentration and rate of PSA increase. Cancer. 2006;106:320–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kristal AR, Arnold KB, Schenk JM, et al. Race/ethnicity, obesity, health related behaviors and the risk of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: results from the prostate cancer prevention trial. J Urol. 2007;177:1395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.065. quiz 1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kristal AR, Arnold KB, Schenk JM, et al. Dietary patterns, supplement use, and the risk of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:925–34. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh PC. Re: The Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial: design, biases and interpretation of study results. P. J. Goodman, I. M. Thompson, Jr., C. M. Tangen, J. J. Crowley, L. G. Ford and C. A. Coltman, Jr., J Urol, 175: 2234-2242, 2006. J Urol. 2006;176:2744. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00284-9. author reply 2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson IM, Tangen CM, Lucia MS. The Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial and the future of chemoprevention. BJU Int. 2008;101:933–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilt TJ, Macdonald R, Hagerty K, et al. 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors for prostate cancer chemoprevention: an updated Cochrane systematic review. BJU Int. 2010;106:1444–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kramer BS, Hagerty KL, Justman S, et al. Use of 5alpha-reductase inhibitors for prostate cancer chemoprevention: American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Urological Association 2008 Clinical Practice Guideline. J Urol. 2009;181:1642–57. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Superko HR, King S., 3rd Lipid management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a new strategy is required. Circulation. 2008;117:560–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.667428. discussion 568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearce KA, Furberg CD, Psaty BM, Kirk J. Cost-minimization and the number needed to treat in uncomplicated hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1998;11:618–29. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00488-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiysonge CS, Bradley H, Mayosi BM, et al. Beta-blockers for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD002003. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002003.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsons JK, Carter HB, Partin AW, et al. Metabolic factors associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2562–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parsons JK, Sarma AV, McVary K, Wei JT. Obesity and benign prostatic hyperplasia: clinical connections, emerging etiological paradigms and future directions. J Urol. 2009;182:S27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McVary KT, Roehrborn CG, Avins AL, et al. Update on AUA guideline on the management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2011;185:1793–803. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.01.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]