Abstract

Background

HIV infection is associated with greater risk of precancerous lesions and cervical cancer in women. However, several factors remain unclarified regarding the association between HIV infection and HPV detection, especially among those with HIV type 2 versus type 1 infection and severely immunocompromised persons.

Objectives

To evaluate HPV overall and type-specific detection among HIV-infected and uninfected women in Senegal.

Study Design

Detection of HPV DNA for 38 genotypes in cervical swabs using PCR-based methods was evaluated in HIV-positive (n=467) and HIV-negative (n=2139) women participating in studies in Senegal. Among HIV-1 and/or HIV-2 positive women, CD4 counts were assessed. Adjusted multivariable prevalence ratios (PR) were calculated.

Results

The prevalence of any HPV DNA and multiple HPV types was greater among HIV-infected individuals (78.2% and 62.3%, respectively) compared with HIV-negative women (27.1% and 11.6%). This trend was also seen for HPV types 16 and 18 (13.1% and 10.9%) compared to HIV-negative women (2.2% and 1.7%). HIV-infected women with CD4 cell counts less than 200 cells/µl had a higher likelihood of any HPV detection (PRa 1.30; 95% CI 1.07–1.59), multiple HPV types (PRa 1.52; 95% CI 1.14–2.01), and HPV-16 (PRa 9.00; 95% CI 1.66–48.67), but not HPV-18 (PRa 1.20, 95% CI 0.45–3.24) compared to those with CD4 counts 500 cells/µl or above.

Conclusion

HIV-infected women, especially those most severely immunocompromised, are more likely to harbor HPV. Measures to prevent initial HPV infection and subsequent development of cervical cancer through focused screening efforts should be implemented in these high risk populations.

Background

Infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) is a universally recognized risk factor for cervical cancer and for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, its precursor lesions1–3. Of the known oncogenic types, HPV types 16 and 18 are responsible for up to 70% of cancers4–6. HPV detection is considerably more common among women infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) compared to uninfected women7–14. Furthermore, women infected with HIV are known to be at increased risk of HPV-associated disease, including cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)15,16. HIV-induced immunosuppression may limit the immune system’s ability to effectively eliminate HPV infection, leaving an individual at greater risk of developing CIN or cancer9. However, the exact etiologic pathway between HIV-induced immunosuppression, HPV infection, and its clinical sequalae has yet to be clearly established.

CD4 lymphocyte count is an important prognostic marker of risk for AIDS-associated clinical events and death, and CD4 cell counts of less than 200 cells per µl indicate severe immuno-suppression17. It is hypothesized that HIV-induced immunosuppression, through the lowering of CD4 T-cells, may increase the risk of HPV detection, HPV persistence, and subsequent development of cervical neoplasia18–21. Limited data exist to confirm the relationship between measurement of CD4 count and HPV detection, however, and the information that does exist has not been entirely corroborative10,18,22–25. In addition, little is known concerning the effect of CD4 count on HPV type-specific detection, including the most commonly-detected oncogenic types, HPV-16 and HPV-18.

Objectives

Our objective was to investigate the relationship between overall and type-specific HPV detection and HIV infection, with special focus on the effect of CD4 count on HPV detection among HIV-infected individuals.

Study Design

Data collection

This study consisted of cross-sectional baseline data from women who participated in research studies in Dakar, Senegal between 2000 and 2010, and included women presenting to an outpatient primary care clinic (Pikine) considered at low risk for sexually transmitted infections including HIV (HIV prevalence below 1%) and an outpatient infectious disease clinic (Fann) serving high risk populations (HIV prevalence >10%)26. The aims of these studies were to investigate the epidemiology of HPV and its association with HIV-associated immune responses, DNA methylation, and cancer control approaches, as described previously27,28. All participants provided written informed consent upon enrollment, under approval of the Human Subjects Committees of the University of Washington and the Université Cheikh Anta Diop, Dakar/Ministry of Health. Subjects were older than 15 years of age, and were excluded from participation if they were pregnant or did not have an intact cervix. Upon enrollment, a structured interview soliciting demographic and medical information (including reproductive and sexual history) was given. Medical and gynecologic exams were carried out, and blood samples were collected to determine patients’ HIV-1 and HIV-2 status, and for lymphocyte subset analysis. Cervical swab samples were obtained for HPV detection.

HIV Serology and Lymphocyte Analysis

Serologic assays for HIV-1 and HIV-2 were performed on patients’ baseline blood samples using a two-test sequence, as previously described26,27,29,30. First, serum samples were tested for the presence of either HIV-1 or HIV-2 antibodies (HIV 1/2 EIA; Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur or Determine HIV 1/2; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL). A second confirmatory immunoassay was then applied to distinguish HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies (Multispot, Genetic Systems; ImmunoComb BiSpot, Orgenics, Yavne, Israel). Blood samples were used to calculate CD4 lymphocyte data for HIV-positive participants, measured per microliter of blood (cells/µl). Cell counts were performed using the fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) Count analyzer (Becton-Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

HPV DNA Detection

Specimens were tested for HPV DNA with a polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) assay using MY09 and MY11 L1 consensus primers, with amplification of the cellular β-globin gene as a control31. Genomic DNA was isolated from 200 µl of the digested samples using QIAamp DNA blood mini kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) for most samples. DNA isolation was performed on 43 (1.6%) samples without the Qiagen assay due to protocol differences between studies. For these samples, digestion was performed with 20 µg/ml proteinase K at 37°C for 1 h, and genomic DNA was ethanol precipitated from 200 µl of the digested samples. The presence of HPV DNA was determined by PCR amplification followed by dot blot hybridization for all samples, and positive samples were subsequently genotyped for type-specific HPV. Of all samples, 16 (0.6%) were genotyped using the Roche line blot, which detected 27 HPV types (6, 11, 16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 40, 42, 45, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, 82, 83, and 84)32. The vast majority of samples were tested using the Roche Linear array assay (2000–2005)33 or a liquid bead microarray assay34,35 (2005–2010), which detected 37 types, with the addition of HPV types 61, 62, 64, 67, 69, 70, 71, 72, 81, IS39 (a subtype of HPV 82), and CP6108 (also known as HPV 89).

Statistical Analysis

We evaluated the association between HIV serostatus (positive versus negative) and overall and type-specific HPV detection (HPV types 16 and 18). Among HIV-positive women, the associations between HIV type (HIV-1 vs. HIV-2 vs. dual HIV-1/HIV-2), CD4 count, anti-retrovirus (ARV) treatment, and HPV detection were evaluated. Log binomial regression (with robust variance) was used for all analyses, and results were reported as prevalence ratios as HPV detection was common among women. Cervical HPV DNA types were classified according to their oncogenic potential, with HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68 classified as high-risk types34.

Potential confounding factors were chosen a priori, and included age, age at first sexual intercourse, lifetime number of sexual partners (continuous) as well as smoking, study clinic, and use of Qiagen DNA purification (dichotomous)29,35. To reduce the possibility of confounding, women who reported undertaking commercial sex work (n=108) were excluded from this analysis. Univariate and multivariable models were used to assess the relationship between HIV status, HIV type, CD4 count, ARV use, and HPV detection. STATA version 11.0 was used (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX).

Results

The median age of women was 43 years (range 15 to 84). Compared to HIV-uninfected women (n=2139), women with HIV-1 and/or HIV-2 infection (n=467) were more likely to be younger, be widowed or separated, initiated sex at a younger age, and had a greater number of lifetime sexual partners (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic, sexual behavior and disease characteristics of Senegalese study population, by HIV statusa

|

HIV-1 and/or HIV-2 positive |

HIV-negative | |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Total | 467 | 2139 |

| Clinic | ||

| Pikine primary care clinic | 16 (3.4) | 1668 (78.0) |

| Fann ID clinic | 451 (96.6) | 471 (22.0) |

| Age (years) | ||

| <35 | 179 (38.3) | 411 (19.2) |

| 35–39 | 82 (17.6) | 297 (13.9) |

| 40–44 | 85 (18.2) | 370 (17.3) |

| ≥45 | 121 (25.9) | 1061 (49.6) |

| Marital status | ||

| Monogamously married | 139 (30.1) | 850 (39.9) |

| Polygamously married | 98 (21.2) | 925 (43.4) |

| Never married | 27 (5.8) | 74 (3.5) |

| Separated/Divorced | 74 (16) | 145 (6.8) |

| Widowed | 124 (26.8) | 136 (6.4) |

| Alcohol use | 10 (3.3) | 21 (1.1) |

| Smoker | 6 (1.9) | 14 (0.8) |

| No contraceptive use | 408 (88.7) | 1752 (82.3) |

| Education | ||

| None | 261 (56.4) | 1121 (52.8) |

| Primary | 136 (29.4) | 643 (30.3) |

| Secondary or above | 66 (14.3) | 361 (17.0) |

| Age at first sex (years) | ||

| <15 | 157 (33.6) | 579 (27.1) |

| 16–20 | 215 (46.0) | 1042 (48.7) |

| ≥21 | 95 (20.3) | 518 (24.2) |

| Lifetime partners | ||

| 1 | 205 (46.3) | 1372 (65.3) |

| 2–5 | 228 (51.5) | 702 (33.4) |

| >5 | 10 (2.3) | 26 (1.2) |

| HIV type | ||

| HIV-1 | 373 (79.9) | --- |

| HIV-2 | 78 (16.7) | --- |

| HIV 1/2 | 16 (3.4) | --- |

| CD4 count (cells/µl) | ||

| ≥500 | 79 (29.9) | --- |

| 200–499 | 99 (37.5) | --- |

| <200 | 86 (32.9) | --- |

| ARV treatment | 86 (81.9) | --- |

Includes the following missing values: marital status (14), alcohol use (450), smoker (447), no contraceptive use (17), education (18), age at first sex (62), lifetime partners (63), CD4 count among HIV-infected women (203), and ARV treatment among HIV-infected women (282)

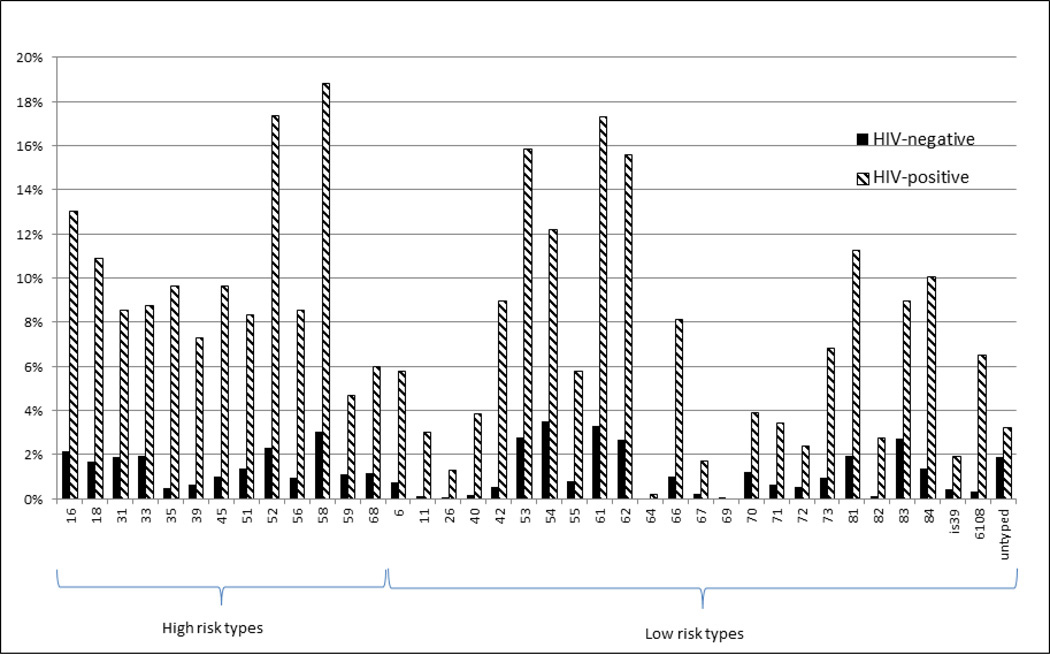

HIV-infected women were more likely to have any HPV detected (78.2% vs. 27.1%, p<0.001), to have high-risk HPV detected (61.5% vs. 15.2%, p<0.001), and to have multiple types of HPV detected (62.3% vs. 11.6%, p<0.001) than HIV-uninfected women. The most common types of high-risk HPV detected among HIV-positive individuals were types 58 (18.8%), 52 (17.3%), 16 (13.1%), 18 (10.9%), 35 (9.6%), and 45 (9.6%) (Figure 1). Among HIV-negative women, the mostly commonly detected high-risk HPV types included types 58 (3.0%), 52 (2.3%), 16 (2.2%), 33 (2.0%), 31 (1.9%), and 18 (1.7%). After adjustment for confounders, HIV-positive women were more likely to have any HPV (PRa: 2.28, 95% CI 2.01–2.58), high-risk HPV (PRa: 3.17, 95% CI 2.66–3.79), and multiple HPV types (PRa: 4.51, 95% CI 3.71–5.49) detected compared to HIV-negative women (Table 2). HIV-positive women were also more likely to have HPV type 16 and HPV type 18 (HPV-16 PRa: 4.76, 95% CI 2.63–8.63; HPV-18 PRa: 5.77, 95% CI 3.47–9.60). Upon stratification by age, similar patterns of HPV detection were observed in both younger (<35 years old) and older women, with HPV increased in those with HIV infection, although HPV prevalence was lower in women above age 35. Among all women with detectable HPV, those with HIV infection had a higher proportion of high risk types (78.6% vs 56.1%) and multiple types (79.7% vs 42.8%) than HIV-negative women. Similarly, the proportion of HPV type 16 (16.7% versus 7.9%) and type 18 (14.0% versus 6.2%) was also higher among HIV-positive women than HIV-negative women with detectable HPV.

Figure 1.

Type-specific prevalence of HPV among HIV-positive and HIV-negative womena.

NOTE: Although this graphic contains a color, black-and-white reproduction is intended.

Table 2.

Prevalence ratio (PR) estimates for the association of HIV-infection (HIV-1 and/or HIV-2 positive versus HIV-negative) with the detection of overall and type-specific HPV infections.

| HIV-1 and/or HIV-2 positive n (%) |

HIV-negative n (%) |

Univariable PR | 95% CI | Multivariable PRa | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All women | N=467 | N=2139 | ||||

| Any HPV | 365 (78.2) | 579 (27.1) | 2.89 | 2.65–3.14 | 2.28 | 2.01–2.58 |

| High-risk HPV | 287 (61.5) | 325 (15.2) | 4.04 | 3.58–4.58 | 3.17 | 2.66–3.79 |

| Multiple HPV types | 291 (62.3) | 248 (11.6) | 5.37 | 4.69–6.16 | 4.51 | 3.71–5.49 |

| HPV 16 | 61 (13.1) | 46 (2.2) | 6.07 | 4.20–8.79 | 4.76 | 2.63–8.63 |

| HPV 18 | 51 (10.9) | 36 (1.7) | 6.49 | 4.29–9.82 | 5.77 | 3.47–9.60 |

| Among women <35 years | N=179 | N=411 | ||||

| Any HPV | 166 (92.7) | 125 (30.4) | 3.04 | 2.57–3.59 | 2.43 | 1.97–2.99 |

| High-risk HPV | 131 (73.2) | 73 (17.8) | 4.10 | 3.24–5.20 | 3.25 | 2.45–4.31 |

| Multiple HPV types | 132 (73.7) | 47 (11.4) | 6.42 | 4.80–8.59 | 5.27 | 3.71–7.49 |

| HPV 16 | 26 (14.5) | 8 (1.9) | 7.43 | 3.42–16.15 | 7.62 | 2.08–27.98 |

| HPV 18 | 25 (14.0) | 7 (1.7) | 8.17 | 3.59–18.60 | 7.75 | 2.97–20.21 |

| Among women ≥35 years | N=288 | N=1728 | ||||

| Any HPV | 199 (69.1) | 454 (26.3) | 2.82 | 2.54–3.13 | 2.21 | 1.90–2.58 |

| High-risk HPV | 156 (54.2) | 252 (14.6) | 3.98 | 3.43–4.63 | 3.21 | 2.58–4.01 |

| Multiple HPV types | 159 (55.2) | 201 (11.6) | 5.09 | 4.33–5.98 | 4.11 | 3.24–5.22 |

| HPV 16 | 35 (12.2) | 38 (2.2) | 5.93 | 3.82–9.20 | 4.15 | 2.02–9.05 |

| HPV 18 | 26 (9.0) | 29 (1.7) | 5.77 | 3.45–9.63 | 5.17 | 2.74–9.76 |

Adjusted for age (continuous), age at first sex (continuous), lifetime sexual partners (continuous), use of qiagen column for DNA processing, and study clinic.

Of the 467 HIV-positive subjects included, 373 were infected with HIV-1, 78 with HIV-2, and 16 were dually infected with HIV-1 and HIV-2. Of those with HIV types -1, -2, and dual infection, the average (SD) CD4 count was 357.6 (291.0), 535.7 (337.9), and 268.4 (267.2) cells/µl, respectively. HIV-1 (79.6%), HIV-2 (70.5%) and dually (81.3%) infected women were similarly likely to have any HPV, multiple types of HPV, and HPV-16 detected (Table 3). HIV-2 infected women were less likely to be infected with high risk HPV (PR=0.69, 95% CI 0.54–0.90) and HPV-18 (PR=0.32, 95% CI 0.10–1.00) compared to HIV-1 infected women, although these differences were attenuated with adjustment for other covariates including age and CD4 count. Dually HIV-1 and HIV-2 infected women were similar t o HIV-1 infected women with regards to HPV prevalence.

Table 3.

Prevalence ratio estimates for the association of HIV infection and detection of overall and type-specific HPV infection (n=467).

| Any HPV | Multiple HPV infections | High risk HPV | HPV16 | HPV18 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable PR (95% CI) |

Multivariable PR (95% CI) |

Univariable PR (95% CI) |

Multivariable PR (95% CI) |

Univariable PR (95% CI) |

Multivariable PR (95% CI) |

Univariable PR (95% CI) |

Multivariable PR (95% CI) |

Univariable PR (95% CI) |

Multivariable PR (95% CI) |

|

| HIV typea | ||||||||||

| HIV-1 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| HIV-2 | 0.89 (0.76–1.03) | 0.90 (0.70–1.16) | 0.82 (0.66–1.03) | 0.93 (0.66–1.31) | 0.69 (0.54–0.90) | 0.90 (0.63–1.30) | 1.25 (0.69–2.24) | 2.15 (0.81–5.73) | 0.32 (0.10–1.00) | 0.46 (0.06–3.61) |

| Dual HIV-1/2 | 1.02 (0.80–1.30) | 1.02 (0.75–1.39) | 1.07 (0.76–1.51) | 1.07 (0.75–1.53) | 1.06 (0.76–1.49) | 1.13 (0.79–1.63) | 1.52 (0.53–4.37) | NAe | 1.55 (0.54–4.47) | NAe |

| CD4 count (cells/µl)b,c | ||||||||||

| ≥500 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 200–499 | 1.02 (0.83–1.26) | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) | 1.17 (0.87–1.59) | 1.06 (0.78–1.46) | 1.23 (0.91–1.67) | 1.27 (0.93–1.74) | 1.60 (0.30–8.52) | 0.82 (0.11–6.27) | 0.77 (0.27–2.23) | 0.93 (0.33–2.66) |

| <200 | 1.35 (1.14–1.60) | 1.30 (1.07–1.59) | 1.79 (1.37–2.32) | 1.52 (1.14–2.01) | 1.78 (1.36–2.34) | 1.67 (1.25–2.25) | 8.73 (2.09–36.4) | 9.00 (1.66–48.7) | 1.20 (0.45–3.24) | 1.53 (0.58–4.03) |

| ARV treatmentd | ||||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 1.06 (0.89–1.26) | 0.97 (0.76–1.23) | 1.35 (1.06–1.73) | 1.09 (0.79–1.51) | 1.31 (1.04–1.65) | 1.10 (0.78–1.54) | 1.92 (0.81–4.57) | 1.10 (0.43–2.86) | 1.14 (0.50–2.59) | 1.26 (0.42–3.79) |

Adjusted for age (continuous), age at first sex (continuous), lifetime sexual partners (continuous), use of Qiagen column for DNA processing, CD4 count and study clinic. Excludes 203 missing values for CD4 count.

Adjusted for age (continuous), age at first sex (continuous), lifetime sexual partners (continuous), use of Qiagen column for DNA processing, and study clinic.

Wald test values for CD4 count trend in multivariable analysis: HPV-positive (p=0.005), HPV multiple infection (p=0.002), High risk HPV (p<0.001), HPV16 (p=0.005), HPV18 (p=0.599)

Adjusted for age (continuous), age at first sex (continuous), lifetime sexual partners (continuous), use of Qiagen column for DNA processing, study clinic, and CD4 count (continuous). Excludes 282 missing values for ARV treatment and 203 missing values for CD4 count.

Multivariable analysis not conducted due to small number of HPV type-specific infections in dual HIV-1/2 infected women

HIV-positive study participants were evaluated by level of immune function, as measured by CD4 count. Amongst HIV-infected women, HPV DNA was detected in 67.1% of women with CD4 counts greater than or equal to 500 cells/µl, 68.7% of those with CD4 counts between 200 and 499 cells/µl, and 90.7% of women with CD4 counts less than 200 cells/µl. Compared to those with CD4 counts measuring 500 cells/µl or above, women with CD4 counts below 200 cells/µl were more likely to have any HPV (PRa: 1.30, 95% 1.07–1.59), multiple HPV types (PRa: 1.52, 95% CI 1.14–2.01), and high-risk HPV detected (PRa: 1.67, 95% CI 1.25–2.25). Severely immunosuppressed women were also more likely to have HPV-16 (PRa: 9.00, 95% CI 1.66–48.7) but not HPV-18 (PRa: 1.20, 95% CI 0.45–3.24) DNA detected. Among all HIV-positive women with detectable HPV, those with CD4 less than 200 cells/µl had a higher proportion of high-risk HPV compared to those with CD4 levels at 500 cells/µl or above(87.2% versus 66.0%). Compared to women with CD4 counts ≥500 cells/µl, women who were moderately immunosuppressed (CD4 counts 200–499 cells/µl) were not at appreciably greater risk of any HPV, multiple HPV, or high-risk HPV detection. Compared to HIV-infected women who were not taking ARV at the time of study, and controlling for CD4 count and other potential confounders, those taking ARV showed no significant difference in HPV overall, high-risk, multiple, or HPV-16 or HPV-18 type-specific detection.

Discussion

Among our large sample of HIV-1 and/or HIV-2 positive and HIV-negative women, we observed positive associations between HIV infection and HPV DNA detection, multiple types, and high risk HPV types, especially HPV-16 and HPV-18. These results are comparable to findings from other African settings, and are likely due to increased exposure to HPV in oculations after high-risk sexual activity, increased susceptibility to HPV due to HIV-associated immunosuppression, and the potential for re-activation of latent HPV virus due to immunosuppression12,33,36–40. Moreover, among HIV-infected women in our sample, those with highest levels of immunosuppression (CD4 < 200 cells/µl) were most likely to have any, multiple, and high-risk types of HPV detected. This finding is consistent with most, although not all, of other studies evaluating this association10,18,22–25.

HPV type 16 and 18 detection was more likely among HIV-positive compared to HIV-negative women in our sample. Further, we observed a higher proportion of HPV-16 infections among HIV-positive women with detectable HPV compared to HIV-negative women with detectable HPV. We also noted a greater likelihood of HPV-16 among HIV-infected women with lowest CD4 counts, although the broad confidence interval of this estimate limits any definitive interpretation. Another study has noted a similar trend between low CD4 count and HPV-16 detection41, although others have not23,24. A study by Firnhaber et al conducted in South Africa found that, even among women with negative cytology, a significant association between CD4 count lower than 200 cells/µl and HPV-16 detection existed41. Firnhaber’s finding among women with normal cytology may imply that the association between CD4 count and HPV-16 detection is present even after assuming that prevalent HPV-16 infections are likely to be over-represented in our cross-sectional design. This suggests that HIV-infected women, at least to some degree through the mechanism of CD4-cell depletion, are at increased risk of HPV infection, including the most oncogenic HPV types. One possible explanation for these findings is that reactivation of latent HPV viral infections occurs more frequently in the presence of HIV infection, especially with severe immunosuppression38,41. From a biological perspective, HIV-mediated susceptibility to HPV infection may occur through several direct and indirect pathways, including the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines leading to an interference of normal inflammatory responses to HPV42.

An increased risk of high-risk HPV infection may warn of a predisposition to adverse cervical events among HIV-infected women, especially those most immunocompromised. Indeed, HIV-positive women have been shown to have both higher rates of CIN prevalence and of low-grade lesion persistence43,44. One recent report has even provided a biological mechanism for increased cervical carcinogenesis via HIV infection through the mediation of COX-2 expression, a molecule linked to cervical carcinogenesis45.

The most common high-risk genotypes among HIV-infected women in the present study were 58, 61, 52, 62 and 53, then 16. This finding is not unlike other studies in Africa, which note that non −16 and −18 HR-HPV types were most common among HIV-infected women10,13,46,47. A meta-analysis by Clifford et al showed that HPV types 52 and 58 accounted for a high proportion of all HR-HPV infections among HIV-infected African women12. Among HIV-negative women from our study, a number of HPV types including 54, 61, 58, 53, 62, 83, and 52 were detected more often than 16, a finding that is supported by another recent study in Senegal among HIV-negative women >35 years of age48. As the currently available HPV vaccines only protect against types 16 and 18, a high prevalence of other high-risk types could infer an added risk of non −16 and −18 cervical carcinogenesis49–51.

Few other studies have evaluated HPV overall and HPV type-specific detection by HIV type (1 versus 2)14,52. Both HIV-1 and HIV-2, when compared to HIV-negative women, were associated with a greater likelihood of HPV detection in our study, as was also found by Langley et al52. HIV-2 infection is known to cause a slower loss of CD4 cells and lower risk of immunosuppression than HIV-1, and HIV-2 infected individuals generally demonstrate a more effective and sustained T-cell immunity27. These biological differences may suggest that a higher amount of circulating antiviral T-cells would help HIV-2 infected women to better control new or existing HPV infections, and in our study, the prevalence of high risk HPV types, including HPV-18, was lower in HIV-2 compared to HIV-1 infected women. However, after taking into account subject age and CD4 counts, HIV-1 and HIV-2 infected individuals were similar with respect to HPV prevalence.

Several limitations in our study should be noted. Information on ARV treatment was only available for a portion (39.6%) of subjects. This missingness was primarily due to protocol differences between studies contributing data to this analysis; ARV treatment information was not routinely collected for two of the four studies included. However, among women with known ARV status, and accounting for CD4 count, HPV detection was similar between those with and without ARV use. Furthermore, several recent studies have suggested that there is limited effect of ARV on HPV viral persistence36,41,53,54, indicating that it is possible to interpret associations between HPV and HIV infection outside of the context of ARV. In addition, because HIV viral load data was not available for many of the HIV-infected women in this analysis, the influence of virologic suppression due to ART was not assessed. Finally, it was beyond the scope of our aims to evaluate the association between HIV, HPV, and cervical abnormalities identified by cytology in the current analysis.

Our most noteworthy findings are that HIV-positive women were more likely to have HPV DNA detected, including the most common high-risk types. Among HIV-infected women, those most severely immunosuppressed had the greatest likelihood of HPV detection and were most likely to have multiple HPV types detected. High risk HPV types, especially HPV-16, were detected in both HIV-1 and HIV-2 infected women with severe immunosuppression, most likely due to their increased persistence and/or rate of reactivation. Future studies among HIV-positive individuals could serve to clarify the impact of this increased HPV infection on the future development of cervical neoplasia and cancer. Further, the higher HPV prevalence and increased proportion of infections with multiple types among HIV-infected women does indicate that differential cervical cancer screening approaches may be warranted among HIV-infected women.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Original data collection was supported by grants AI48470, CA097275, CA111187 and CA 115713 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This research was supported by the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI027757) supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers (NIAID, NCI, NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, NHLBI, NIA).

We would like to thank the Dakar area outpatient health clinics and all study participants, as well as Haby Diallo-Agne, Diouana Ba, Papa Ousmange Diop, Maguette Diongue, Sophie Chablis, Jane Kuyppers, Steve Cherne, Donna Kenney, and Fatou Traore for laboratory processing, analysis, and supervision and Alison Starling, John Lin, Joshua Stern, Fatou Faye-Diop, and Fatima Sall for forms development and data management.

Abbreviations

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- HR-HPV

high-risk human papillomavirus

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- CIN

cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

- ARV

antiretroviral

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Human Subjects Committees of the University of Washington and the Université Cheikh Anta Diop, Dakar/Ministry of Health.

References

- 1.Koutsky L, Holmes K, Critchlow C, et al. A cohort study of the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3 in relation to papillomavirus infection. N Engl J Med. 1992 Oct;327(18):1272–1278. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210293271804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muñoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, et al. The causal link between human papillomavirus and invasive cervical cancer: a population-based case-control study in Colombia and Spain. Int J Cancer. 1992 Nov;52(5):743–749. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walboomers J, Jacobs M, Manos M, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999 Sep;189(1):12–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clifford GM, Smith JS, Aguado T, Franceschi S. Comparison of HPV type distribution in high-grade cervical lesions and cervical cancer: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2003 Jul;89(1):101–105. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S. Chapter 1: Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer--burden and assessment of causality. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2003;(31):3–13. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guan P, Howell-Jones R, Li N, et al. Human papillomavirus types in 115,789 HPV-positive women: a meta-analysis from cervical infection to cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012 Nov;131(10):2349–2359. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun X, Kuhn L, Ellerbrock T, Chiasson M, Bush T, Wright TJ. Human papillomavirus infection in women infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. N Engl J Med. 1997 Nov;337(19):1343–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711063371903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minkoff H, Feldman J, DeHovitz J, Landesman S, Burk R. A longitudinal study of human papillomavirus carriage in human immunodeficiency virus-infected and human immunodeficiency virus-uninfected women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998 May;178(5):982–986. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70535-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahdieh L, Muñoz A, Vlahov D, Trimble C, Timpson L, Shah K. Cervical neoplasia and repeated positivity of human papillomavirus infection in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive and - seronegative women. Am J Epidemiol. 2000 Jun;151(12):1148–1157. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jamieson DJ, Duerr A, Burk R, et al. Characterization of genital human papillomavirus infection in women who have or who are at risk of having HIV infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Jan;186(1):21–27. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.119776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palefsky J. Cervical human papillomavirus infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in women positive for human immunodeficiency virus in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Curr Opin Oncol. 2003 Sep;15(5):382–388. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200309000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clifford GM, Gonçalves MA, Franceschi S Group HaHS. Human papillomavirus types among women infected with HIV: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2006 Nov;20(18):2337–2344. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000253361.63578.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blossom DB, Beigi RH, Farrell JJ, et al. Human papillomavirus genotypes associated with cervical cytologic abnormalities and HIV infection in Ugandan women. J Med Virol. 2007 Jun;79(6):758–765. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rowhani-Rahbar A, Hawes S, Sow P, et al. The impact of HIV status and type on the clearance of human papillomavirus infection among Senegalese women. J Infect Dis. 2007 Sep;196(6):887–894. doi: 10.1086/520883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grulich A, van Leeuwen M, Falster M, Vajdic C. Incidence of cancers in people with HIV/AIDS compared with immunosuppressed transplant recipients: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007 Jul;370(9581):59–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishnan A, Levine AM. Malignancies in women with H IV infection. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 2008 Jul;4(4):357–368. doi: 10.2217/17455057.4.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.[CDC] CfDCaP. HIV Classification: CDC and WHO Staging Systems. [Accessed January 18th, 2013];2013 http://hab.hrsa.gov/deliverhivaidscare/clinicalguide11/cg-205_hiv_classification.html.

- 18.Denny L, Boa R, Williamson AL, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and cervical disease in human immunodeficiency virus-1-infected women. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun;111(6):1380–1387. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181743327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delmas M, Larsen C, van Benthem B, et al. Cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions in HIV-infected women: prevalence, incidence and regression. European Study Group on Natural History of HIV Infection in Women. AIDS. 2000 Aug;14(12):1775–1784. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200008180-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor G, Wolff T, Khanna N, Furth P, Langenberg P. Genital dysplasia in women infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17(2):108–113. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.17.2.108. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drogoul-Vey MP, Marimoutou C, Robaglia-Schlupp A, et al. Determinants and evolution of squamous intraepithelial lesions in HIV-infected women, 1991–2004. AIDS Care. 2007 Sep;19(8):1052–1057. doi: 10.1080/09540120701295242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veldhuijzen NJ, Braunstein SL, Vyankandondera J, et al. The epidemiology of human papillomavirus infection in HIV-positive and HIV-negative high-risk women in Kigali, Rwanda. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:333. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palefsky JM, Minkoff H, Kalish LA, et al. Cervicovaginal human papillomavirus infection in human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV)-positive and high-risk HIV-negative women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999 Feb;91(3):226–236. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh DK, Anastos K, Hoover DR, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and cervical cytology in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected Rwandan women. J Infect Dis. 2009 Jun;199(12):1851–1861. doi: 10.1086/599123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strickler H, Palefsky J, Shah K, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 and immune status in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003 Jul;95(14):1062–1071. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.14.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heitzinger K, Sow PS, Dia Badiane NM, et al. Trends of HIV-1, HIV-2 and dual infection in women attending outpatient clinics in Senegal, 1990–2009. Int J STD AIDS. 2012 Oct;23(10):710–716. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2012.011219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng NN, Kiviat NB, Sow PS, et al. Comparison of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific T-cell responses in HIV-1- and HIV-2-infected individuals in Senegal. J Virol. 2004 Dec;78(24):13934–13942. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13934-13942.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feng Q, Balasubramanian A, Hawes SE, et al. Detection of hypermethylated genes in women with and without cervical neoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005 Feb 16;97(4):273–282. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hawes S, Critchlow C, Sow P, et al. Incident high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions in Senegalese women with and without human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and HIV-2. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006 Jan;98(2):100–109. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gottlieb GS, Sow PS, Hawes SE, et al. Equal plasma viral loads predict a similar rate of CD4+ T cell decline in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1- and HIV-2-infected individuals from Senegal, West Africa. J Infect Dis. 2002 Apr;185(7):905–914. doi: 10.1086/339295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuypers JM, Critchlow CW, Gravitt PE, et al. Comparison of dot filter hybridization, Southern transfer hybridization, and polymerase chain reaction amplification for diagnosis of anal human papillomavirus infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1993 Apr;31(4):1003–1006. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.4.1003-1006.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weaver BA, Feng Q, Holmes KK, et al. Evaluation of genital sites and sampling techniques for detection of human papillomavirus DNA in men. J Infect Dis. 2004 Feb;189(4):677–685. doi: 10.1086/381395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ng'ayo MO, Bukusi E, Rowhani-Rahbar A, et al. Epidemiology of human papillomavirus infection among fishermen along Lake Victoria Shore in the Kisumu District, Kenya. Sex Transm Infect. 2008 Feb;84(1):62–66. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.027508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, et al. A review of human carcinogens--Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009 Apr;10(4):321–322. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmes RS, Hawes SE, Touré P, et al. HIV infection as a risk factor for cervical cancer and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in Senegal. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009 Sep;18(9):2442–2446. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Vuyst H, Lillo F, Broutet N, Smith J. HIV, human papillomavirus, and cervical neoplasia and cancer in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008 Nov;17(6):545–554. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282f75ea1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meys R, Gotch FM, Bunker CB. Human papillomavirus in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus: an immune reconstitution-associated disease? Br J Dermatol. 2010 Jan;162(1):6–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strickler H, Burk R, Fazzari M, et al. Natural history and possible reactivation of human papillomavirus in human immunodeficiency virus-positive women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005 Apr;97(8):577–586. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Theiler RN, Farr SL, Karon JM, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus reactivation in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women: risk factors for cervical viral shedding. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Jun;115(6):1150–1158. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e00927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dartell M, Rasch V, Kahesa C, et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence and type distribution in 3603 HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in the general population of Tanzania: the PROTECT study. Sex Transm Dis. 2012 Mar;39(3):201–208. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31823b50ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Firnhaber C, Zungu K, Levin S, et al. Diverse and high prevalence of human papillomavirus associated with a significant high rate of cervical dysplasia in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women in Johannesburg, South Africa. Acta Cytol. 2009 Jan-Feb;53(1):10–17. doi: 10.1159/000325079. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palefsky J. Biology of HPV in HIV infection. Adv Dent Res. 2006;19(1):99–105. doi: 10.1177/154407370601900120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Massad L, Riester K, Anastos K, et al. Prevalence and predictors of squamous cell abnormalities in Papanicolaou smears from women infected with HIV-1. Women's Interagency HIV Study Group. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999 May;21(1):33–41. doi: 10.1097/00126334-199905010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.La Ruche G, Leroy V, Mensah-Ado I, et al. Short-term follow up of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions associated with HIV and human papillomavirus infections in Africa. Int J STD AIDS. 1999 Jun;10(6):363–368. doi: 10.1258/0956462991914276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fitzgerald DW, Bezak K, Ocheretina O, et al. The effect of HIV and HPV coinfection on cervical COX-2 expression and systemic prostaglandin E2 levels. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012 Jan;5(1):34–40. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Desruisseau AJ, Schmidt-Grimminger D, Welty E. Epidemiology of HPV in HIV-positive and HIV-negative fertile women in Cameroon, West Africa. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2009:810596. doi: 10.1155/2009/810596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mbulawa ZZ, Marais DJ, Johnson LF, Boulle A, Coetzee D, Williamson AL. Influence of human immunodeficiency virus and CD4 count on the prevalence of human papillomavirus in heterosexual couples. J Gen Virol. 2010 Dec;91(Pt 12):3023–3031. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.020669-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xi L, Touré P, Critchlow C, et al. Prevalence of specific types of human papillomavirus and cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions in consecutive, previously unscreened, West-African women over 35 years of age. Int J Cancer. 2003 Mar;103(6):803–809. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harper D, Franco E, Wheeler C, et al. Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004 Nov 13–19;364(9447):1757–1765. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17398-4. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ault KA. Human papillomavirus vaccines and the potential for cross-protection between related HPV types. Gynecol Oncol. 2007 Nov;107(2 Suppl 1):S31–S33. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jenkins D. A review of cross-protection against oncogenic HPV by an HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted cervical cancer vaccine: importance of virological and clinical endpoints and implications for mass vaccination in cervical cancer prevention. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Sep;110(3 Suppl 1):S18–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Langley CL, Benga-De E, Critchlow CW, et al. HIV-1, HIV-2, hu man papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia in high-risk African women. AIDS. 1996 Apr;10(4):413–417. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199604000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahdieh-Grant L, Li R, Levine A, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions in human immunodeficiency virus-positive women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004 Jul;96(14):1070–1076. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fife K, Wu J, Squires K, Watts D, Andersen J, Brown D. Prevalence and persistence of cervical human papillomavirus infection in HIV-positive women initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009 Jul;51(3):274–282. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a97be5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]